Abstract

Effect of selenium (Se) supplementation on the selenoprotein and lipid metabolism gene expression patterns in ruminants, especially in lambs is not yet fully understood. The aim of study was to evaluate the effect of Se supplementation on the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression patterns of selected selenoproteins and genes related to lipid metabolism in growing lambs. The experiment was conducted on 48 Polish Merino lambs divided into two groups (n = 24): control (C)—lambs fed with a basal diet (BD) with no Se supplementation, and supplemented (S)—lambs fed with a BD, supplemented with 0.5 mg Se/kg as sodium selenate for 8 weeks. Expression of 12 selenoproteins and six genes related to lipid metabolism was analyzed in the liver and longissimus dorsi (LD) muscle of growing lambs by qPCR. Significant differences were found in the expression of GPX1, GPX2, SEPM, SEPW1, SEP15, SEPGS2, and TXNRD1 in the liver, and GPX1, SEPP1, SEPN1, SEPW1, SEP15, and MSRB1 in the LD muscle between S and C lambs. Se supplementation mainly upregulated SEPW1, SEP15 (P < 0.001; P < 0.01) mRNA expression in the liver, and GPX1, SEPP1, SEPN1, SEPW1 (P < 0.001; P < 0.01) in the muscle of S group. On the other hand, significant decrease in GPX2 (P < 0.01), SEPM (P < 0.001), and SEPHS2 (P < 0.01) mRNA expression levels were observed in the liver of S group of lambs. Se supplementation did not affect PON1, LXRα, and PPARα mRNA expression levels, but a significant increase in mRNA levels of APOE and LPL in the LD muscle (P < 0.05) as well as LPL (P < 0.05) in the liver were noticed in the group of Se supplemented lambs. Our study confirmed that, in lambs, similarly to other species, mRNA expression patterns of several selenoproteins highly depend on dietary Se levels, and their expression is ruled by hierarchical principles and tissue-specific mechanisms. Moreover, the study showed that changes Se intake leads to different levels of genes expression related with lipid metabolism.

Keywords: Selenium supplementation, Lambs, mRNA expression, Selenoprotein genes, Lipid metabolism genes, Liver, Muscle tissue

Introduction

Along with the development of nutrigenomics, increased interest in the molecular mechanism of macro- and micronutrient action, its influence on human and animal genomes, and consequently—their health. Particular attention was aimed at selenium (Se), a trace mineral and an essential bioactive nutrient in the human and animals’ diet [1]. It was indicated that Se plays an important role in the nervous system biology, immune functions, reproduction, muscle metabolism, chemoprevention, redox reactions, and many others [2].

In livestock animals, including ruminants, Se deficiency induces a number of diseases, like nutritional muscular dystrophy [3], cardiomyopathy [4], hepatic degeneration [5], and reproduction disturbances [6].

In recent years, some studies showed that physiological functions of Se are considered to be mediated through selenoproteins [7]. At least 25 selenoprotein genes in animals and humans have been identified and several families of selenoproteins have been classified according to their biological function: (1) peroxidase and reductase activity; (2) hormone metabolism; (3) protein folding; (4) redox signalling; (5) Sec synthesis, and (6) selenium transport [2, 6, 8, 9]. Among these selenoproteins, the important are glutathione peroxidase family (GPXs), thioredoxin reductase (TRXRs), iodothyronine deiodinase (DIOs), and selenoprotein W, N, and P [2, 10]. In recent years, new groups of selenoproteins have been classified including SEP15, SEPHS2, SEPM, MSRB1, and selenoproteins I, N, V, O, H, T, K, and S, but the function of many of them is still unknown [8].

Selenoproteins are extensively expressed in animals, but the expression patterns and the effect of Se on their messenger RNA (mRNA) levels varied from different tissues and species. Different levels of expression were observed in the brain, liver, spleen, testis, thyroid, as well as in cardiac and skeletal muscles [11]. Selenoproteins, such as GPXs, were found to express in the liver, kidney, and muscle [5], whereas SELW and SELN mRNA transcripts were detected in various kinds of tissues, especially more abundant in muscles [12].

The effect of dietary Se deficiency and Se supplementation on the expression of selenoprotein genes has been studied in rats [13], mice [14], pigs [3, 15], cattle [16], and chickens [5]. The synthesis of selenoproteins is affected by the levels of Se supplementation, and their mRNA expression is controlled in a hierarchical manner [17]. In mammals GPX1, GPX3, and SEPP1 mRNA levels were dramatically decreased with Se deficiency [18], in contrast to several other selenoproteins including GPX4, SEPP1, TXNRD1, and DIO1, which mRNA levels were relatively unchanged in the liver, kidney, thyroid, and other tissues [15, 19].

Recently, studies on animal models [20] and well as human trial [21] showed that changes in Se intake lead to altered mRNA expression of genes associated with the cholesterol and lipid metabolism [22]. Se deficiency was related to an increase in the plasma cholesterol, whereas Se supplementation led to decrease in total cholesterol and triglyceride levels [23]. Pinto et al. [24] reported that high-Se diets increased gene expression of FoxO1 and PGC-1α in the porcine skeletal muscle and enhanced mRNA expression of SREPP-1 and LPL in the adipose tissue. A number of studies also confirmed that Se supplementation can affect lipid metabolism in ruminants [25]. The effect of Se supplementation on the modification of fatty acid composition in the direction of increasing the content of PUFAs, especially CLA isomers in lambs’ meat and liver [26] as well as in cow’s milk [27] and goat [28] has been reported.

Currently, the regulation of specific gene expression in response to changes in Se nutrition is being deeply studied in rodents and pigs as well as in humans, but there are no studies in ruminants, especially in lambs. Our objective in this study, therefore, was to investigate how oral Se supplementation in form of selenate (0.5 mg Se/kg) change the mRNA expression patterns of selected selenoprotein genes (GPX1, GPX2, GPX4, SEPP1, SEPM, SEPN1, SEPW1, SELO, SEP15, SEPHS2, TXNRD1, and MSRB1) and genes related to lipid metabolism (LPL, LXRα, and PPARα) as well as cholesterol metabolism (PON1, APOE, and DHCR24) in the liver and loin (longissimus dorsi) muscle of growing Polish Merino lambs.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Diet

The experiment was conducted on 48 single born Polish Merino ram-lambs housed in the Institute Farm of the IGAB PAS in Jastrzębiec, Poland. At 8 weeks all lambs were weaned and fed with a basal diet (BD) ad libitum for 2 weeks to adjust their Se status (Table 1). After adaptation period, the animals were transferred individually to straw-bedded pens and divided into two groups (n = 24): I—control (C)—lambs fed ad libitum with a basal diet (BD) with no Se supplementation, and II—supplemented (S)—lambs fed ad libitum with a BD supplemented per os with 0.5 mg Se/kg as sodium selenate (Na2SeO4) for 8 weeks. The BD was composed of oats (40 %), triticale (29 %), soybean meal (19.5 %), rapeseed oilcake (10 %), limestone (1 %), and NaCl (0.5 %). Concentration of native Se in BD was 0.1 mg/kg dry matter (DM). Additionally, during the supplementation period about 0.1 kg meadow hay/lamb/day was offered in order to ensure proper rumen function (0.09 mg Se/kg DM). The individual intake of BD was recorded daily. Body weights of individual lambs were recorded at the beginning of Se supplementation and then weekly. To prepare plasma samples, blood was collected from individual lambs at the beginning and final of the experiment. The plasma Se concentration was determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) (Optima 5300 DV, Perkin Elmer). At 18 weeks, lambs were slaughtered and liver and longissimus dorsi (LD) samples were collected. The tissue samples were immediately frozen by liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of feeds (g/kg DM)

| Item | Basal diet (BD)a | Meadow hay |

|---|---|---|

| Organic matter | 912 | 922 |

| Crude protein | 192 | 82 |

| Crude fiber | 106 | 303 |

| Ether extract | 36 | 20 |

| NDF | 282 | 566 |

| ADF | 124 | 361 |

| Se (selenate) (mg/kg DM) | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| Zn (mg/kg DM) | 27.2 | 15.1 |

aThe concentrate was composed of 40 % oat meal, 29 % wheat-rye meal, 19.5 % soybean meal, 10 % rapeseed cake, 1 % limestone, and 0.5 % NaCl

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was isolated with the High Pure RNA Tissue Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) from liver and longissimus dorsi muscle samples, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A qualitative and quantitative assessment of the isolated RNA was performed on ND-1000 NanoDrop (NanoDrop Technologies, USA) spectrophotometer. Only samples with more than 100 ng RNA and absorbance ratios A260/280 and A260/230 of around 2.0 were used for further analyses. To confirm the RNA quality, a quick electrophoretic analysis was conducted using a BioAnalyzer (Agilent, USA). The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the Transcription First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Diagnostics, Switzerland). 1.0 μg of RNA was denatured at 65 °C for 10 min in the presence of 50 μM oligo(dT). The reverse-transcription mixture (20 μl in total volume) contained 13 μl of RNA, 4 μl of reverse transcriptase buffer, 2 μl of 10 mM dNTP, 0.5 μl of protector RNase Inhibitor (40U/μl), and 0.5 μl of reverse transcriptase (20U/μl). The mixture was incubated in 50 °C for 60 min, then at 85 °C for 5 min, and finally stored at −20 °C.

Primer Design

Primers for gene expression were designed with Primer3Plus (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/) in accordance to GenBank Ovis aries sequences and amplicon sequence complied with exon-exon boundaries (Table 2). The relative mRNA abundances of 17 genes were assayed. Selected targets included 12 selenoprotein genes (glutathione peroxidase 1, GPX1; glutathione peroxidase 2, GPX2; glutathione peroxidase 4, GPX4; selenoprotein 1, SEPP1; selenoprotein W1, SEPW1, selenoprotein N1, SEPN1; thioredoxin reductase 1, TXNRD1; selenoprotein 15, SEP15; selenophosphate synthetase 2, SEPHS2; selenoprotein M, SEPM; selenoprotein O, SELO; methionine sulfoxide reductase B1, MSRB1), three genes associated with lipid metabolism (lipoprotein lipase, LPL; liver X receptor α, LXRα; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, PPARα) and three genes involved in cholesterol metabolism (paraoxonase 1, PON1; apolipoprotein E, APOE; 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase, DHCR24).

Table 2.

Genes and primers used for relative quantification by real-time PCR (qPCR) in the liver and longissimus dorsi muscle of lambs

| Target gene | Primer sequences | Product length | GeneBank ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | F: ACCACTTTGGCATCGTGGAG | 75 bp | NM_001190390.1 |

| R: GGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCTG | |||

| ACTB | F: CTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCCT | 178 bp | NM_001009784.1 |

| R: GCAGAAAGAGATCACTGCCC | |||

| GPX1 | F: CCTGGTCGTACTCGGCTTC | 154 bp | XM_004018462.1 |

| R: CCTTCTCGCCATTCACCTC | |||

| GPX2 | F: GGGCAGTGCTGATTGAGAAT | 273 bp | XM_004010720.1 |

| R: TTCAGGTAGGCGAAGACAGG | |||

| GPX4 | F: GGGAGTAATGCGGAGATCAA | 210 bp | XM_004023249.1 |

| R: CATACCGCTTCACCACACAG | |||

| SEPP1 | F: GACCGTGGTTGCTCTTCTTC | 222 bp | XM_004017013.1 |

| R: GGTTGGTCTTCTTCTTGTTGG | |||

| SEPM | F: TGTCGCTGAGTGGAATTCG | 210 bp | XM_012112767.1 |

| R: ACTGGAACCGTCTACAAGGC | |||

| SEPN1 | F: GGATCCTGGACCACAAGATG | 217 bp | XM_004023208.1 |

| R: TGGCCGCAGGATATAGTAGC | |||

| SEPN1 | F: TCGTCGTCCGAGTTGTTTACT | 210 bp | XM_004023205.1 |

| R: GAAACTTGCTCTCCGTGTCC | |||

| SELO | F: AGGTTCGGATCCTTCGAGAT | 164 bp | XM_004007676.1 |

| R: TGTCTGCACATGGTCTCC | |||

| SEPHS2 | F: TTCAACATGGCTACCCTCAA | 167 bp | XM_004020905.1 |

| R: GCAATGATGGGCAGATTATG | |||

| SEP15 | F: TTCAAACGGTCTCTGCATTG | 251 bp | XM_004002164.1 |

| R: TCCTGACGAAAGCTTGGACT | |||

| TXNRD1 | F: GCTTTGGAATGTGCTGGATT | 193 bp | XM_004006684.1 |

| R: TCTCCTTCGATGGTTTGGTC | |||

| MSRB1 | F: TGTCGTTCTGCAGCTTCTTC | 162 bp | XM_004020710.1 |

| R: CACTGTCAGCATGGATGGTC | |||

| PON1 | F: TACAGCCCAGATGACGTTCG | 210 bp | XM_004007735.1 |

| R: TGTCACAGGGTCCACGGATA | |||

| LXRα | F: GGTACAACCCTGGAAGTGAGA | 160 bp | XM_004016449.1 |

| R: CAAGGCAAACTCAGCATCATT | |||

| DHCR24 | F: GCGGGTTGGAAAGTACAAGA | 229 bp | XM_004002011.1 |

| R: ATGGGATGAAGACTCGATGC | |||

| APOE | F: CTACGGCGAGACCTTCAACA | 210 bp | XM_004016047.1 |

| R: CCCAAAGGGACGGGTATCTC | |||

| PPARα | F: ATGGCTTCATAACCCGTGAG | 206 bp | XM_004007050.1 |

| R: AATCCCCTCCTGCATTTTCT | |||

| LPL | F: TTCAACCACAGCAGCAAAAC | 210 bp | NM_001009394.1 |

| R: AAACTTGGCCACATCCTGTC |

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assays (qPCR)

qPCR was performed using LightCycler 96 System (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) in 96-well optical reaction plates with a total reaction volume of 10 μl. The reaction mixture consisted of 1 μl of each primer (20 pM, Table 2), 5 μl of SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland), 2 μl of PCR-grade water, and 50 ng of cDNA. The amplification program consisted of: 10 min of initial denaturation at 95 °C, 40 cycles of denaturation (10 s, 95 °C), annealing (9 s, 59–61 °C), and elongation (20 s, 72 °C). qPCR amplifications were conducted in triplicates for both target and reference genes. Negative controls containing the template RNA and all PCR reagents, but not reverse transcriptase, were included to determine the RNA purity from DNA contamination. The qPCR data were normalized using two reference genes: β-actin (ACTB) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH). The relative mRNA abundance of target genes in tissue samples were determined using Δ cycle threshold (ΔCt) method in which, the ΔCt value is the difference between the target and reference gene (ΔCt = Cttarget–Ctreference). For each of the target gene the normalized relative expression was calculated (2−ΔΔCt, were ΔΔCt = ΔCt sample–ΔCt control). The expression of the target gene was set as 1, assuming its Ct at 27 (selenoproteins), 30 (lipid metabolism genes) and the reference gene GAPDH/ACTB at 22 and its ΔCt was used as the control. PCR reactions of each sample were conducted in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Fold-changes of mRNA expression between groups and its statistical significance were evaluated with ANOVA procedure (SAS 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary NC, USA). Data was presented as means ± SE and the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Growth Performance and Se Concentration in Plasma

The average body weight of lambs at the start and after supplementation period was 14.2 ± 0.3 and 31.2 ± 0.5 kg, and there was no difference between C and S groups of lambs (P > 0.05). The average daily feed intakes were 0.97 ± 0.2 kg of BD and 0.085 kg of meadow hay per lamb and were similar among the C and S groups of lambs. There was no observed difference in consumption during the study (P > 0.05). Mean daily Se intake per lamb was 0.15 mg Se/kg for C group and 0.65 mg Se/kg for S group. Plasma Se concentrations before the experiment were 1.11 ± 0.09 μmol/l in C group and 1.12 ± 0.11 μmol/l in S group, respectively. At the end of experiment, the final plasma Se concentrations noticeably increased (P < 0.05) in lambs from S group (1.47 ± 0.19 μmol/l) vs. C group (1.19 ± 0.15 μmol/l) (P < 0.05).

Abundance of Selenoproteins mRNA

To investigate the effect of differences in Se status on mRNA expression of antioxidant selenoproteins, we determined the hepatic and muscle expression patterns of GPX1, GPX2, GPX4, SEPP1, SEPM, SEPN1, SEPW1, SELO, SEP15, SEPHS2, TXNRD1, and MSRB1 genes. Our results showed that expression of these genes responded to dietary Se concentration in three patterns. In the first one, Se supplementation resulted in increased (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001) GPX1, SEPW1, SEP15, and TXNRD1 mRNA levels in the liver (Fig. 1a) and GPX1, SEPP1, SEPN1, SEPW1, SEP15, and MSRB1 in the LD muscle of S group (0.65 mg Se/kg) (Fig. 1b) compared with the C (0.15 mg Se/kg) group of lambs. In the second pattern, higher (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.01) mRNA levels were manifested in the C group (0.15 mg Se/kg) than in the S group (0.65 mg Se/kg) including GPX2, SEPM, and SEPHS2 in the liver; no significant differences were found in the LD muscle. The third pattern exhibited similar mRNA expression in the liver and muscle of S group; the expression of GPX1, SEPW1, and SEP15 was upregulated by Se supplementation in both tissues. However, Se supplementation had nonsignificant effect on the expression of GPX4, SEPP1, SEPN1, SELO, and MSRB1 in the liver, and GPX2, GPX4, SEPM, SELO, SEPHS2, and TXNRD1 in the LD muscle.

Fig. 1.

Effects of dietary Se concentrations on mRNA expression levels of selected selenoproteins (a) in the liver and (b) in the longissimus dorsi muscle. Data are mean ± SE, n = 24. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

mRNA Levels of Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes

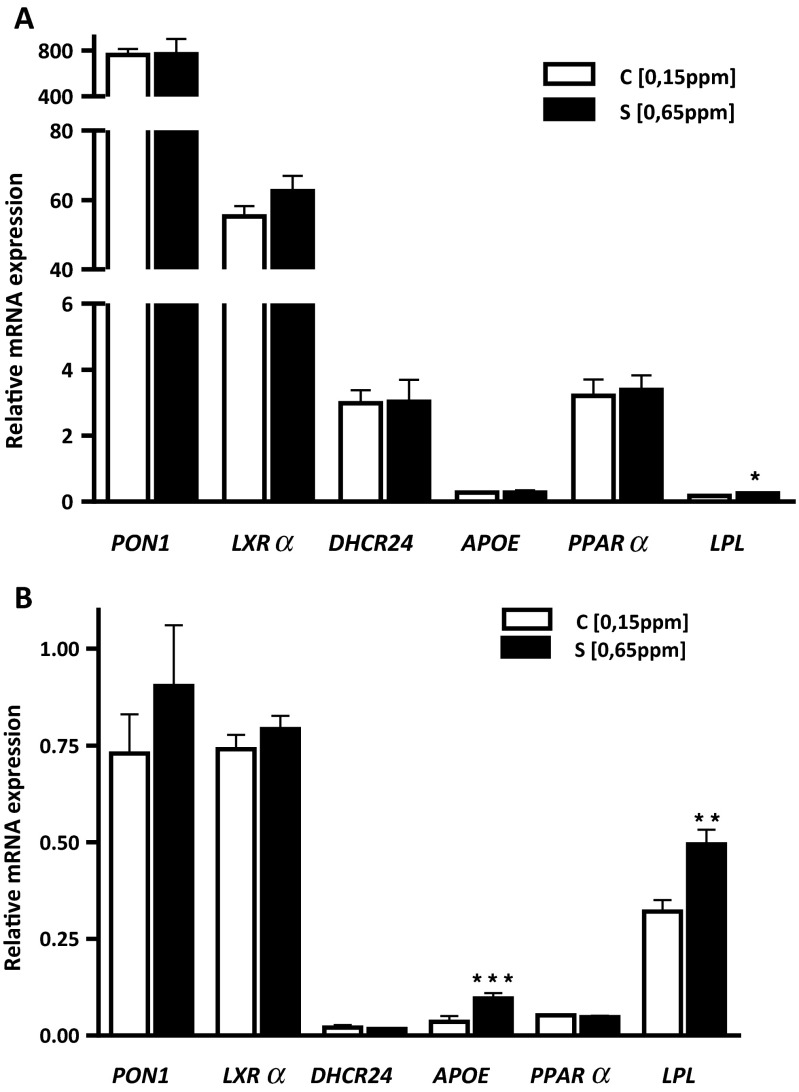

To investigate the effect of Se supplementation on mRNA level of genes involved in the regulation of the lipid and cholesterol metabolism, we assessed the hepatic and muscle expression patterns of PON1, LXRα, LPL, APOE, PPARα, and DHCR24 genes. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, Se supplementation did not alter the mRNA levels of PON1, LXRα, and PPARα; mRNA levels of these genes remained unchanged both in the liver and LD muscle. On the other hand, Se supplementation significantly stimulated the mRNA expression of the LPL in both tissues and the APOE in the skeletal muscle. The significantly higher LPL mRNA level in the liver (P < 0.05) and LD muscle (P < 0.01) and APOE in the LD muscle (P < 0.001) was observed in the S (0.65 mg Se/kg) vs. C (0.15 mg Se/kg) group of lambs.

Fig. 2.

Effects of dietary Se concentrations on mRNA expression levels of lipid metabolism genes (a) in the liver and (b) in the longissimus dorsi muscle. Data are mean ± SE, n = 24. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Discussion

General Remarks

In our study, the dietary Se concentration of the S lambs group was the upper recommended level by the NRC [29], whereas C group received 0.15 mg/kg DM of naturally occurring Se in feeds used. Body weight of lambs, daily feed intake, and gain efficiency in our experiment were not altered by the dietary Se status, which confirmed previous results in studies with lambs [30, 31], pigs [15], chickens [5], cattle [25], and goats [32]. On the other hand, the data of this study showed noticeably increased (P < 0.05) level of plasma Se concentration in lambs from S group vs. C group, which was consistent with findings reported in other species including pig [3, 15], chicken [18], goat [32], cattle [25], and turkey [33].

Effect of Se Supplementation on mRNA Level of Selenoprotein Genes in the Liver and Muscle

qPCR analysis showed that investigated genes were expressed in both tissues, but relative higher mRNA levels were found in the liver, which indicates that the liver is more responsive to changes in dietary Se levels than the muscle. It is known, that the liver ranks higher than the muscles in the hierarchy of Se source and metabolism [34] and that the hepatic antioxidant system plays an important role in mammals [35]. As in the previous studies [30, 31], our results confirmed that changes in Se intake alter the mRNA level of lamb selenoproteins, and the effects varies significantly between different selenoproteins and different tissues. These variations could reflect the hierarchy of selenoproteins expression, indicating, that some are more sensitive to changes in Se intake than others [19].

Numerous studies have shown that GPX1, SEP15, and SELW1 mRNA levels increased in response to dietary Se supplementation in the pig [15], chicken, [5] and sheep [30]. It was also demonstrated that hepatic expression of GPX1, SEPW1, and SEP15 was highly and significantly downregulated by Se deficiency [18]. On the other hand, Liu et al. [11] reported that high-Se diet (3.0 mg Se/kg) decreased SEPW1 mRNA level in the liver of pigs, compared with the 0.3 mg Se/kg diet. Our results showed that GPX1, SEPW1, SEP15 transcripts were upregulated both in the liver and muscle of Se supplemented group of lambs (0.65 mg Se/kg). Increased mRNA levels of GPX1 in the liver and muscle, SEP15 in the liver, and SEPW1 in the muscle were noticed. Moreover, muscle GPX1 and SEPW1 mRNA expression levels were more sensitive to regulation by Se status than SEP15. In the light of these results, one could hypothesize that SEPW1 may participate in cell redox defense in mature muscle fibers and be involved in the prevention of skeletal muscle degeneration [3]. SEPW1 is probably involved in the etiology of sheep nutritional myopathy, the white muscle disease [36]. Less is known about role of SEP15, but its antioxidative function was recently indicated in some mammalian and human cell lines [37]. Our results showed that Se supplementation had a significant effect on GPX1 and SEPW1 mRNA expression both in the liver and muscle, suggesting high sensitivity of these selenoproteins on changes in dietary Se intake. Similar results were also reported in rat [13] and pig liver [15]. Furthermore, elevated muscle SEPN1 mRNA levels by dietary Se supplementation (0.65 mg Se/kg) were consistent with the fact, that the muscle is the major source of this protein [38], and results of previous studies have clearly shown the possible role of SEPN1 protein during muscle development, cell proliferation, and regeneration [38]. The effect of Se concentration on SEPN1 expression has been also studied in pig liver [15] and chicken muscles [39]. Zhang et al. [39] reported that high-Se diet (1.50 mg Se/kg), compared with a diet containing 0.15 mg Se/kg resulted in the elevation of SEPN1 mRNA levels in skeletal muscles. In contrast to the muscle, the effect of Se excess on SEPN1 mRNA level in pig liver appeared to be insignificant [15].

The downregulation of GPX2, SEPM, and SEPHS2 mRNA levels in the liver of S lambs fed 0.65 mg Se/kg, compared with C fed 0.15 mg Se/kg, appears to be unique. Because these decreases were not noticed in the muscle, the expression of GPX2, SEPM, and SEPHS2 in the liver seems to be more sensitive to the higher level of dietary Se and/or exposure of liver cells to oxidative stress. Zhou et al. [15] reported that GPX2 mRNA level in pig pituitary (fed 0.3 mg Se/kg) was significantly higher than in the liver and decreased in the pituitary of pig fed 3.0 mg Se/kg. Opposite trend has been observed in chicken liver [39], and rat muscle [13]. In case of SEPHS2, pigs supplemented 0.3 and 3.0 mg Se/kg had significantly higher SEPHS2 mRNA level in the heart compared with those with Se deficiency in the diet [11, 15]. Both GPX2 and SEPHS2 are high in the selenoproteins hierarchy and their mRNA expression is little affected, therefore significantly decreased GPX2, SEPM, and SEPHS2 in the liver of S group (0.65 mg Se/kg) may be a consequence of higher Se toxicity in the form of selenate. Nevertheless, our data showed that these genes may play protective role by the reduction of oxidative stress toxicity in the liver, but also that tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms controlling their mRNA expression are involved. A recent finding suggest that effect of Se on the mRNA level of these genes is achieved not only through pre-translational mechanisms, but also in the post-transcriptional step by altering the miRNAs profile [40].

It is noteworthy, that results of our study showed lack of common pattern of the GPX1, GPX2, and GPX4 expression. Similarly to previous findings reported in rats [41] and pig [15], level of the GPX4 mRNA in the liver and muscle of both groups of lambs exhibited insignificant response to changes in Se status. Our results suggest that GPX1 and GPX2 mRNA may be more sensitive to regulation by Se status than GPX4, and different response of mRNA expression to dietary Se might exist between selenoproteins GPX1, GPX2, and GPX4. In the case of SEPP1, the high hepatic SEPP1 mRNA level in comparison with expression of other selenoprotein genes is consistent with the fact, that liver is the major source of plasma SEPP1 and is responsible for Se transport to skeletal muscles and other organs, where Se levels are maintained by means of a ApoER2 receptor-mediated uptake of SEPP1 [42].

Effect of Se Supplementation on mRNA Level of Lipid Metabolism Genes in the Liver and Muscle

The findings on the Se dietary regulation of lipid metabolism-related genes in ruminants are very limited, and, to our knowledge, the gene expression patterns of PON1, LXRα, LPL, APOE, PPARα, and DHCR24 in the liver and muscle of lambs have not been previously reported. Our results showed that changes in Se supply not only lead to changes in the mRNA expression of selenoproteins but also significantly alter mRNA level of the genes, playing essential role in the regulation of the triglycerides and fatty acids metabolism. In our study, we showed that Se supplementation significantly upregulated LPL mRNA expression in the liver and muscle of S (0.65 mg Se/kg) group of lambs. The main function of LPL is to hydrolyze triglycerides (TG) in lipoproteins and release free fatty acids, and its activity is critical for TG-rich lipoprotein clearance. Moreover, the LPL activity also affects HDL level in the blood circulation; a decrease of LPL activity leads to decreased HDL concentration. Observed in our study, elevated level of LPL mRNA expression in the muscle (P < 0.01) of S group of lambs could be associated with higher utilization of fatty acids as energy sources or building blocks for TG, resulting in decrease of the TG in the lamb’s meat. The effect of high-Se diet on LPL mRNA expression has been previously reported by Pinto et al. [24] who showed that in pigs, high-Se diet increased mRNA expression of LPL in the adipose tissue. Moreover, elevated mRNA levels of these genes were significantly correlated with higher activity of plasma GPX1, MSRB1, SELS, and SEPP1 [20].

In our study, the APOE gene was also found to be affected by Se supplementation, and similarly to LPL, significantly higher APOE mRNA levels were found in the muscle vs. liver, which was consistent with the involvement of tissue-specific mechanisms controlling their expression [43]. Although this protein is synthesized primarily in liver, APOE transcripts were found in the kidney [43], adipose tissue [44], and in the skeletal muscles [45]. Earlier studies have clearly demonstrated the role of APOE in many steps of lipoprotein homeostasis such as production, delivery, and utilization of cholesterol in the body [46]. In the plasma, APOE is associated with very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), chylomicron remnants, and a subset of HDL particles [46]; it is also a high affinity ligand for the LDL receptor [47]. It was reported that a Se-deficient diet or targeted removal of a gene that causes complete loss of selenoproteins expression, results in increased plasma cholesterol concentration along with an increase in APOE levels [22]. It was speculated, that this increase was related to higher HDL fraction, which is rich in APOE. Potential mechanisms that may explain these associations are not clear, but recent studies on knock-out mouse (Trsp−/Trsp−) models provided strong evidence, that several selenoproteins such as GPX1, DIO1, SELK, SEPP1, and SEP15 are responsible for the role of Se in the APOE and cholesterol metabolism [22]. The observed common patterns of LPL and APOE mRNA expression in the LD muscle of S (0.65 mg Se/kg) group of lambs may indicate a bidirectional supportive role of these genes in the delivery and metabolism of TG-rich lipoproteins [48]. It was reported that LPL mediates the uptake of APOE-containing lipoproteins via LDL receptor-related protein [49] and that APOE polymorphisms appear to modulate LPL activity [44]. In addition, muscle LPL and APOE mRNA expression may be more sensitive to regulation by dietary Se status. It is therefore likely that Se may regulate lipid metabolism in cells through LPL and APOE, which may have selective roles for either cholesterol or fatty acid metabolism.

Interestingly, outcomes of our study showed that Se supplementation did not affected mRNA expression of PON1, LXRα, PPARα, and DHCR24 genes, but relatively high PON1 and LXRα mRNA expression levels were observed in the liver of both experimental groups of lambs. In agreement with previous report [50], high levels of the PON1 and LXRα transcripts were found in tissues involved in maintaining lipid homeostasis, such as liver, adipocytes, and macrophages [51]. Also, both PON1 and LXRα have a key role in the control of cholesterol homeostasis and fatty acid metabolism [51]. Recently, the beneficial effect of Se supplementation on plasma PON1 activity in the diabetic rats has been investigated [52], but similar to our results, mRNA expression of PON1 in the liver was not affected in the Se treated groups [53]. These findings suggest that PON1 expression may possibly be regulated by Se status at post-transcriptional and/or translational levels.

In summary, our study confirmed that, in lambs, similarly to other species, mRNA expression patterns of several selenoproteins, especially GPX1, SEPN1, SEP15, SEPM, and SEPHS2 highly depend on dietary Se levels, but their expression is ruled by hierarchical principles, and they are regulated by tissue-specific mechanisms controlling their expression. Furthermore, the study showed that changes Se intake leads to different levels of gene expression related with lipid metabolism. The results of our study suggests that Se supplementation promote higher levels of the LPL and APOE gene expression, especially in skeletal muscle and possibly in fatty acid utilization and TG metabolism. Our results provide new insights into the role of Se in these metabolic pathways, indicating that Se is not only an important antioxidant but also a regulator of gene expression. Therefore, further studies on dietary Se levels need be carried out to help us better understand the interactions between nutrients and metabolic pathways.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the National Science Centre (NCN), research project no. 2012/07B/NZ9/02196.

Author Contributions

J-K.E. and B.K. conceived and designed the experiments; J-K.E., B.K., C.M., and W.K., conducted the experiments; B.K. and J-K.E. analyzed the data; M.G. conduced the nutritional and biochemical experiments, P.M. critically revised the paper; J-K.E. wrote the paper and primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APOE

Apolipoprotein E

- ApoER2

Apolipoprotein E receptor 2

- DHCR24

24-dehydrocholesterol reductase

- BD

Basal diet

- ACTB

β-actin

- FOXO1

Forkhead box protein O1

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene

- DM

Dry matter

- GPX1

Glutathione peroxidase 1

- GPX2

Glutathione peroxidase 2

- GPX4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- LPL

Lipoprotein lipase

- LXRα

Liver X receptor α

- miRNA

Micro-ribonucleic acid

- MSRB1

Methionine sulfoxide reductase B1

- NRC

National Research Council

- PGC-1α

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha

- PON1

Paraoxonase 1

- PPARα

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- CLA

Conjugated linoleic acid

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SEPHS2

Selenophosphate synthetase 2

- SEPM

Selenoprotein M

- SELO

Selenoprotein O

- SEPN1

Selenoprotein N1

- SEPP1

Selenoprotein 1

- SEP15

Selenoprotein 15

- SEPW1

Selenoprotein W1

- SREPP-1

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

- TXNRD1

Thioredoxin reductase 1

- TG

Triglycerides

- UTR

Untranslated region

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The experiment was conducted in accordance with established standards for the use of experimental animals and was approved by the III Local Animal Ethical Committee in Warsaw (no. 36/2012).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Standard

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- 1.Ferguson LR, Karunasinghe N. Nutrigenetics, nutrigenomics, and selenium. Front Genet. 2011;25:2–15. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2011.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papp LV, Lu J, Holmgren A, Khanna KK. From selenium to selenoproteins: synthesis, identity, and their role in human health. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:775–806. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loflin J, Lopez N, Whanger PD, Kioussi C. Selenoprotein W during development and oxidative stress. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:1679–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oropeza-Moe M, Wisløff H, Bernhoft A. Selenium deficiency associated porcine and human cardiomyopathies. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;31:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu CP, Fu J, Lin SL, Wang XS, Li S. Effects of dietary selenium deficiency on mRNA levels of twenty-one selenoprotein genes in the liver of layer chicken. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;159:192–198. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehdi Y, Hornick JL, Istasse L, Dufrasne I. Selenium in the environment, metabolism and involvement in body functions. Molecule. 2013;18:3292–3311. doi: 10.3390/molecules18033292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JY, Carlson BA, Xu XM, Zeng Y, Chen S, Gladyshev VN, Lee BJ, Hatfield DL. Inhibition of selenocysteine tRNA[Ser]Sec aminoacylation provides evidence that aminoacylation is required for regulatory methylation of this tRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:814–819. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobanov AV, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Eukaryotic selenoproteins and selenoproteomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1424–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCann JC, Ames BN. Adaptive dysfunction of selenoproteins from the perspective of the triage theory: why modest selenium deficiency may increase risk of diseases of aging. FASEB J. 2011;25:1793–1814. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-180885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasui Y, Hasada K, Yang JG, Koiwai O. Structure and organization of the gene encoding human selenoprotein. Gene. 1996;175:269–270. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Zhao H, Zhang Q, Tang J, Li K, Xia XJ, Wang KN, Li K, Lei XG. Prolonged dietary selenium deficiency or excess does not globally affect selenoprotein gene expression and/or protein production in various tissues of pigs. J Nutr. 2012;142:1410–1416. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Li J, Zhang Z, Sun B, Wang R, Jiang Z, Li S, Xu S. Ubiquitous expression of selenoprotein N transcripts in chicken tissues and early developmental expression pattern in skeletal muscles. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012;146:187–191. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evenson JK, Wheeler AD, Blake SM, Sunde RA. Selenoprotein mRNA is expressed in blood at levels comparable to major tissues in rats. J Nutr. 2004;134:2640–2645. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labunskyy VM, Lee BC, Handy DE, Loscalzo J, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Both maximal expression of selenoproteins and selenoprotein deficiency can promote development of type 2 diabetes-like phenotype in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2327–2336. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou JC, Zhao H, Li JG, Xia XJ, Wang KN, Zhang YJ, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Lei XG. Selenoprotein gene expression in thyroid and pituitary of young pigs is not affected by dietary selenium deficiency or excess. J Nutr. 2009;139:1061–1066. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews JC, Zhang Z, Patterson JD, Bridges PJ, Stromberg AJ, Boling JA. Hepatic transcriptome profiles differ among maturing beef heifers supplemented with inorganic, organic, or mixed (50% inorganic:50% organic) forms of dietary selenium. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;160:321–339. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reszka E, Jabłońska E, Gromadzińska J, Wasowicz W. Relevance of selenoprotein transcripts for selenium status in humans. Genes Nutr. 2012;7:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0246-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang JQ, Li DL, Zhao H, Sun LH, Xia XJ, Wang KN, Luo X, Lei XG. The selenium deficiency disease exudative diathesis in chicks is associated with downregulation of seven common selenoprotein genes in liver and muscle. J Nutr. 2011;141:1605–1610. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.145722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunde RA, Raines AM. Selenium regulation of the selenoprotein and nonselenoprotein transcriptomes in rodents. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:138–150. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng MS, Li X, Liu Y, Zhao H, Zhou JC, Li K, Huang JQ, Sun LH, Tang JY, Xia XJ, Wang KN, Lei XG. A high-selenium diet induces insulin resistance in gestating rats and their offspring. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misu H, Ishikura K, Kurita S, Takeshita Y, Ota T, Saito Y, Takahashi K, Kaneko S, Takamura T. Inverse correlation between serum levels of selenoprotein P and adiponectin in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta A, Carlson BA, Hoffmann VJ, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Loss of housekeeping selenoprotein expression in mouse liver modulates lipoprotein metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:446–5223. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Méplan C. Selenium and chronic diseases: a nutritional genomics perspective. Nutrients. 2015;7:3621–3651. doi: 10.3390/nu7053621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinto A, Juniper DT, Sanil M, Morgan L, Clark L, Sies H, Rayman MP, Steinbrenner H. Supranutritional selenium induces alterations in molecular targets related to energy metabolism in skeletal muscle and visceral adipose tissue of pigs. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;114:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Netto AS, Zanetti MA, Claro GR, de Melo MP, Vilela FG, Correa LB. Effects of copper and selenium supplementation on performance and lipid metabolism in confined brangus bulls. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2014;27:488–494. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.13400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabryszuk M, Czauderna A, Baranowski N, Strzałkowska N, Jóźwik A, Krzyżewski J. The effect of diet supplementation with Se, Zn and vitamin E on cholesterol, CLA and fatty acid contents of meat and liver of lambs. Anim Sci Pap Rep. 2007;25:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ran L, Wu X, Shen X, Zhang K, Ren F, Huang K. Effects of selenium form on blood and milk selenium concentrations, milk component and milk fatty acid composition in dairy cows. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:2214–2219. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pechova A, Misurova L, Pavlata L, Dvorak R. Monitoring of changes in selenium concentration in goat milk during short-term supplementation of various forms of selenium. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2008;121:180–191. doi: 10.1007/s12011-007-8033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NRC . Nutrient requirements of small ruminants: sheep, goats, cervids, and new world camelids. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humann-Ziehank E, Renko K, Mueller AS, Roehrig P, Wolfsen J, Ganter M. Comparing functional metabolic effects of marginal and sufficient selenium supply in sheep. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013;27:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vignola G, Lambertini L, Mazzone G, Giammarco M, Tassinari M, Martelli G, Bertin G. Effects of selenium source and level of supplementation on the performance and meat quality of lambs. Meat Sci. 2009;81:678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavlata L, Chomat M, Pechova A, Misurova L, Dvorak R. Impact of long-term supplementation of zinc and selenium on their content in blood and hair in goats. Vet Med. 2011;56:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Słowińska M, Jankowski J, Dietrich GJ, Karol H, Liszewska E, Głogowski J, Kozłowski K, Sartowska K, Ciereszko A. Effect of organic and inorganic forms of selenium in diets on turkey semen quality. Poult Sci. 2011;90:181–190. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhan X, Wang M, Zhao RQ, Li WF, Xu ZR. Effects of different selenium source on selenium distribution, loin quality and antioxidant status in finishing pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2007;132:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2006.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Huang K, Lei XG. Selenium and diabetes—evidence from animal studies. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:1548–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whanger PD, Weswig PH, Schmitz JA, Oldfield JE. Effects of selenium and vitamin E on blood selenium levels, tissue glutathione peroxidase activities and white muscle disease in sheep fed purified or hay diets. J Nutr. 1977;10:71298–71307. doi: 10.1093/jn/107.7.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun H, Deng T, Fu J. Chicken 15-kDa selenoprotein plays important antioxidative function in splenocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;161:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petit N, Lescure A, Rederstorff M, Krol A, Moghadaszadeh B, Wewer UM, Guicheney P. Selenoprotein N: an endoplasmic reticulum glycoprotein with an early developmental expression pattern. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1045–1053. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang JL, Zhang ZW, Shan AS, Xu SW. Effects of dietary selenium deficiency or excess on gene expression of selenoprotein N in chicken muscle tissues. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;157:234–241. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9893-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maciel-Dominguez A, Swan D, Ford D, Hesketh J. Selenium alters miRNA profile in an intestinal cell line: evidence that miR-185 regulates expression of GPX2 and SEPSH2. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:2195–2205. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss SS, Sunde A. Selenium regulation of transcript abundance and translational efficiency of glutathione peroxidase-1 and −4 rat liver. Biochem J. 2001;357:851–858. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burk RF, Hill KE. Selenoprotein P-expression, functions, and roles in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1441–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srivastava RA, Bhasin N, Srivastava N. Apolipoprotein E gene expression in various tissues of mouse and regulation by estrogen. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;38:91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao J, Katagiri H, Ishigaki Y, Yamada T, Ogihara T, Imai J, Uno K, Hasegawa Y, Kanzaki M, Yamamoto TT, et al. Involvement of apolipoprotein E in excess fat accumulation and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:24–33. doi: 10.2337/db06-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conzález-Calvo L, Joy M, Alberti C, Ripoll G, Molino F, Serrano M, Calvo JH. Effect of finishing period length with α-tocopherol supplementation on the expression of vitamin E-related genes in the muscle and subcutaneous fat of light lambs. Gene. 2014;552:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang ZH, Luque RM, Kineman RD, Mazzone T. Nutritional regulation of adipose tissue apolipoprotein E expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E203–E209. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00118.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto T, Choi HW, Ryan RO. Apolipoprotein E isoform-specific binding to the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Anal Biochem. 2008;372:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Barlingen HH, de Jong H, Erkelens DW, de Bruin TW. Lipoprotein lipase-enhanced binding of human triglyceride-rich lipoproteins to heparan sulfate: modulation by apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein C. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:754–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laatsch A, Panteli M, Sornsakrin M, Hoffzimmer B, Grewal T, Heeren J. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 dependent endosomal trapping and recycling of apolipoprotein E. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng Y, Liu G, Pan Q, Guo S, Yang X. Elevated expression of liver X receptor alpha (LXRα) in myocardium of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Inflammation. 2011;34:698–706. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott J. The liver X receptor and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2195–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr075951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghaffari T, Nouri M, Irannejad E, Rashidi MR. Effect of vitamin e and selenium supplement on paraoxonase-1 activity, oxidized low density lipoprotein and antioxidant defense in diabetic rats. Bioimpacts. 2011;1:121–128. doi: 10.5681/bi.2011.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaur HD, Bansal MP. Studies on HDL associated enzymes under experimental hypercholesterolemia: possible modulation on selenium supplementation. Lipids Health Dis. 2009;8:55. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]