Abstract

Angelica sinensis has been used to attenuate cold-induced cutaneous vasospasm syndrome, such as Raynaud's disease and frostbite, in China for many years. Ferulic acid (PubChem CID: 445858) and Z-ligustilide (PubChem CID: 529865), two major components extracted from Angelica sinensis, had been reported to inhibit vasoconstriction induced by vasoconstrictors. In this study, the pharmacological interaction in regulating cold-induced vascular smooth muscle cell contraction via cold-sensing protein TRPM8 and TRPA1 was analyzed between ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide. Pharmacological interaction on inhibiting [Ca2+]i influx evoked by TRPM8 agonist WS-12 or TRPA1 agonist ASP 7663 as well as cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8 was determined using isobolographic analysis. The isobolograms demonstrated that the combinations investigated in this study produced a synergistic interaction. Combination effect of two components in inhibiting RhoA activation and phosphorylation of MLC20 induced by WS-12 or ASP 7663 was also being quantified. These findings suggest that the therapeutic effect of Angelica sinensis on cold-induced vasospasm may be partially attributed to combinational effect, via TRPM8 and TPRA1 way, between ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide.

1. Introduction

The roots of Angelica sinensis (RAS) are a well-known traditional Chinese medicine which had been used for thousands of years in China. RAS is widely accepted for its anticancer, memory, neuroprotective, and immunoregulatory effects [1]. It has also been used to cure some cold-induced cutaneous vasospasm diseases such as Raynaud's phenomenon and frostbite [2]. Ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide, which proved to be effective in cardiovascular disease, are two major components extracted from Angelica sinensis [3, 4]. However, mechanism of RAS in regulating cold-induced vasospasm is still unknown.

Ion channels, especially Ca2+-permeable channels, play an important role in regulating vascular tone [5]. Members of transient receptor potential (TRP) family that are considered as novel nonvoltage Ca2+ permeable cation channels attract people's attention in vascular research. Several members of TRP family exhibit temperature-sensitive characters [6]. TRP channels, expressed in sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia (TG), are the primary detectors for sensing environmental change and stimuli [7]. Among them, TRPM8 and TRPA1 are sensors for noxious cold and innocuous cool temperature, respectively [6, 8, 9]. TRPM8 can be activated by some cooling compounds, such as menthol or icilin, while TRPA1 can be activated by mustard oil or AITC. Recently, several studies proved that TRPM8 and TRPA1 not only existed in sensory neurons but also could be detected in rat aorta and pulmonary artery [10]. Both of them are involved in the regulation of vascular tone, especially response to cold environment [5, 11, 12].

Local cold exposure leads to an initial vasoconstriction which protects against heat loss, followed by a vasodilation which prevent local area from cold-induced injuries such as frostbite [13]. The complex regulator mechanisms involve a combination of neurotransmitter synthesis and release, Ca2+ homeostasis, adrenergic receptor function, or VSMC contractile ability [14]. Sympathetic nerve, sensory nerve, and nonneuronal factors, such as NOS system, contributed to the cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to local cooling [14, 15]. Contraction of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC), influenced by systems mentioned above, controlled vascular tone directly. Constriction of VSMC can be achieved by an increase of intracellular Ca2+ influx, which is recognized as “calcium-dependent,” as well as an increase of Ca2+ sensitivity, which is recognized as “calcium sensitization” [16]. TRPM8 and TRPA1 could regulate vascular tone through sensory nerve, sympathetic nerve, and NOS system [12, 17].

In order to discuss TRPM8 and TRPA1 direct effect on vascular smooth muscle cell contraction, TRPM8 specific agonist WS-12 and TRPA1 specific agonist ASP 7663 were used. Both “calcium-dependent” pathway and “calcium-sensitization” pathway were explored. Since cold temperature can activate TRPM8 and TRPA1 ion channel, its regulation on TRPM8 and TRPA1 expression was discussed as well. Since prolong exposure to cold environment leads to some local area cold-induced injuries which could be attenuated by application of Angelica sinensis, synergistic effect of ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide on regulating TRPM8/TRPA1 function and expression would be discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide were obtained from National Institutes for food And Drug Control (Beijing, China). WS-12, ASP 7663, ryanodine, 2-APB, and xestospongin C were acquired from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom). Fluo-4, AM, cell permeable, and pluronic F-127 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Rhotekin-RBD bead pulldown kit was from Cytoskeleton (St. Denver, CO, USA). Primary antibodies against MLC and phosphor-MLC were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA).

2.2. Cell Culture

The human aortic smooth muscle cell (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was cultured in smooth muscle cell medium (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% FBS and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

2.3. Calcium Imaging

Human aortic smooth muscle cells on coverslip were loaded with 5 μM fluo-4 and 0.01% pluronic acid in HBSS for 60 min at 37°. Coverslip was placed on fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71, Xuhui District, Shanghai). Fluorescence signal was measured at 561 nm. Images were captured every 4 s for 15 min with a ×5 objective lens and analyzed using ImagJ software. For each coverslip at least 50 cells in each image were included as a region of interest (ROI). The average intensity of ROIs was calculated at each time-point. The highest fluorescence (F max) was recognized as the maximal response to agonist WS-12 or ASP 7663 (50 μM; set at 100%) whereas the baseline fluorescence (F 0) was the weakest and stable fluorescence before agonist added. Change of fluorescence F max/F 0 was recorded.

2.4. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

Cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/dish and incubated with ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, or their combination in the presence of cold stimulation. RNA was extracted from HASMC using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) under manufacturer's instructions. The RNA quantity was estimated by a nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). cDNA was made from 500 ng of total RNA using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TAKARA, Kyoto, Japan). The resulting cDNA was used to perform real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR reactions in triplicate using SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermixes (Bio-Rad, California, USA) and CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, California, USA) operated by CFX Manager Software. RTFQ PCR was initiated with 1 × 98°C for 2 minutes, followed by 39 cycles of 98°C for 2 seconds and 58°C for 5 seconds, and finalized with melt curve for 75°C to 95°C for 10 seconds. Forward and reverse primers were designed and ordered from Sangon Biotech (Songjiang, Shanghai, China). β-actin was used as reference gene. Primer sequences were as follows: TRPM8 forward CAG CAC TGG CAC CTG AAA AC; TRPM8 reverse GGA CTG CGC GAT GTA GAT GA; TRPA1 forward GCT ACT CTC TAA AGG TGC CCA AG; TPRA1 reverse CGT TGT CTT CAT CCA TTA CCA G; β-actin forward GGG AAA TCG TGC GTG ACA TTA AGG; β-actin reverse CAG GAA GGA AGG CTG GAA GAG TG. The expression levels of the target genes were normalized to β-actin.

2.5. Western Blotting

Lysis of HASMC was made in RIPA including protease inhibitor purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Songjiang, Shanghai, China). Lysate concentration was determined using BCA assay and a standard curve. Equal amounts were loaded on 8%–12% Bis-Tris gels, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were probed with appropriate primary antibodies and then incubated with the horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the chemiluminescence detection kit (CST, Beverly, MA, USA).

2.6. Detection of Total and GTP-Bound RhoA

HSMAC were seeded in 60 mm tissue culture dish and grow to 30% confluence. Then they were made quiescent by serum starvation (0% FBS) for 24 hours. Active and GTP-bound RhoA were measure from cell lysates using Rhotekin-RBD bead pulldown assay according to the manufacturer's instruction. Total RhoA was determined by Western blot with an anti-RhoA and was used to normalize GTP-RhoA expression. Activated RhoA in stimulated samples was compared to the level of GTP-RhoA in unstimulated samples.

2.7. Analysis of Combined Drug Effects

We used the Calcusyn software (Biosoft, Version 2.1) to determine drug synergy by the isobolograms and combination index originated from the median effect principle of Chou and Talalay [18]. The isobolograms method, which is formed by selecting a desired fractional affect (Fa), represents the pharmacologic interaction. A straight line was drawn to connect the Fa points plotted with fixed ration between ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide on x- and y-axes to generate isobolograms. Combination data points falling on the line represented an additive drug-drug interaction while points falling below or above the line represented synergism or antagonism. The combination index (CI) was calculated by the following formula [19]: CI = (D)A/(D x)A + (D)B/(D x)B. (D)A and (D)B were the concentrations of drug A and drug B, used in combination to achieve x% drug effect. (D x)A and (D x)B were the concentrations of individual components to achieve the same effect. CI values were generated over a range of Fa levels from 0.05 to 0.90 (5%–90% inhibition). CI of 1 indicated additive effect between the two components whereas CI < 1 or CI > 1 indicated synergism or antagonism separately.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed using 3 individual coverslips of cells and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by the SNK post hoc test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Responses to TRPM8 and TRPA1 Agonist-Evoked Ca2+ Signal

3.1.1. Contribution of Ca2+ Store to TRPM8 and TRPA1 Agonist-Evoked Ca2+ Signal

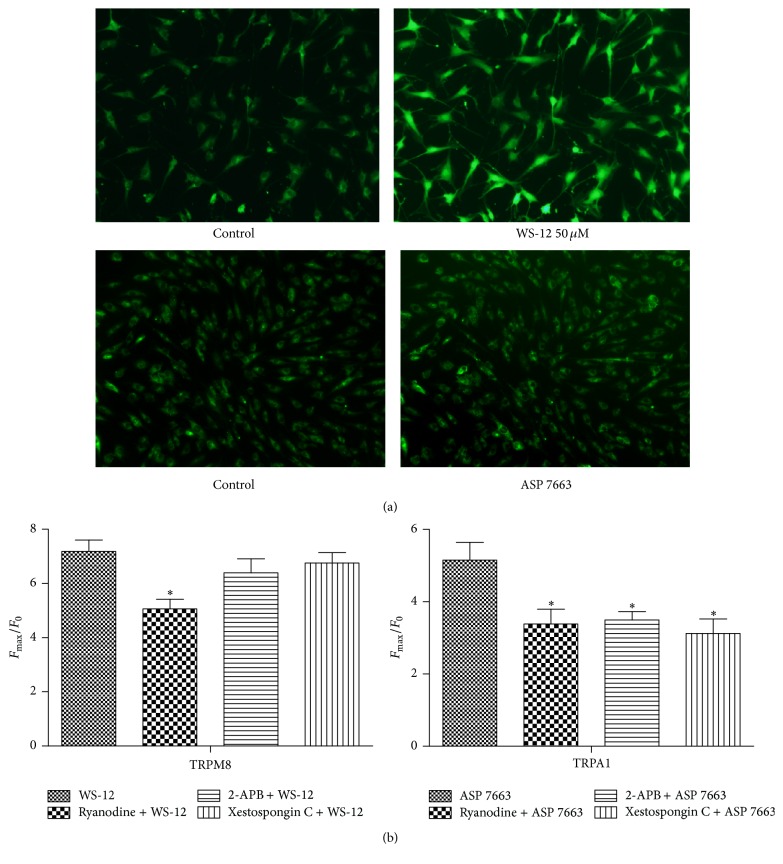

We first examined the effects of TRPM8 specific agonist WS-12 50 μM (F max/F 0 = 7.186 ± 0.8334) and TRPA1 specific agonist ASP 7663 50 μM (F max/F 0 = 5.153 ± 0.9831). As illustrated in Figure 1(a), both of them could induce significant change of fluorescence.

Figure 1.

Contribution of Ca2+ store to TRPM8 and TRPA1 agonist-evoked Ca2+ signal. (a) Images of field of HASMC before (left) and during (right) 50 μM WS-12 (upper) and 50 μM ASP7663 (down) application. (b) WS-12 50 μM or ASP 50 μM-evoked calcium signal was measured in the absence or presence of ryanodine 30 μM or 2-APB 100 μM or xestospongin C 5 μM. ∗Significant difference between control groups (P < 0.05).

TRPM8 and TRPA1 were Ca2+ permeable cation channels which could activate calcium induced calcium release (CICR) through either ryanodine receptor (RYR) or inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R). To assess if Ca2+ release via RYR and IP3R contributes to TRPM8 and TRPA1 agonist-evoked Ca2+ signal, experiments were carried out with the presence of RYR inhibitor or IP3R inhibitor. As shown in Figure 1(b), application of a high concentration of RYR inhibitor ryanodine (30 μM) could significantly reduce both ASP 7663 (F max/F 0 = 3.384 ± 0.8142) and WS-12 (F max/F 0 = 5.066 ± 0.6962) evoked [Ca2+]i, while application of IP3R inhibitor 2-APB (100 μM) or xestospongin C (5 μM) could only reduce ASP 7663 (F max/F 0 = 3.499 ± 0.4609 for 2-APB and F max/F 0 = 3.122 ± 0.6891 for xestospongin C) but not WS-12 (F max/F 0 = 6.395 ± 1.030 for 2-APB and F max/F 0 = 6.76 ± 0.6533 for xestospongin C) evoked [Ca2+]i. These data indicated that Ca2+ release via RYR contributes to TRPM8 agonist-evoked Ca2+ signal, while Ca2+ release via both RYR and IP3R contributes to TRPA1 agonist-evoked Ca2+ signal.

3.1.2. Inhibition of WS-12 and ASP 7663 by Ferulic Acid and Z-Ligustilide Individually

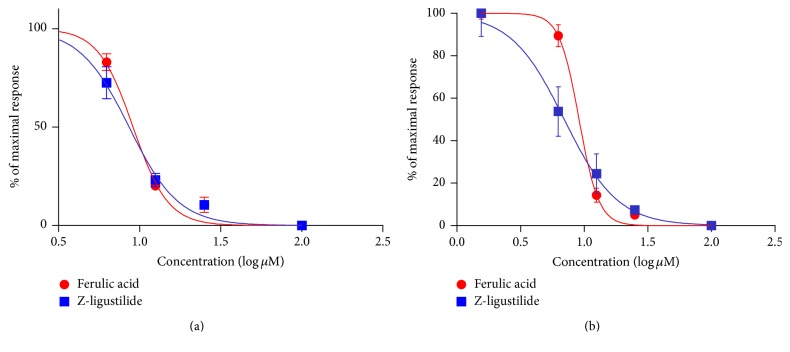

To exclude calcium release through CICR, 10 minutes prior to the challenge with WS-12, cells were first perfused with ryanodine 30 μM. Meanwhile, 10 minutes prior to the challenge with ASP, cells were first perfused with combination of ryanodine 30 μM and 2-APB 100 μM. Next, ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide in the concentrations (μM) 1.55, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 100 followed by WS-12 50 μM or ASP 7663 50 μM were applied. The concentration-response curve can be seen in Figure 2. The fact that increasing concentrations of compounds related to decreasing [Ca2+]i release showed both drugs inhibiting the TRPM8 activated by WS-12 or TRPA1 activated by ASP 7663 in the absence of CICR.

Figure 2.

Effects of ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide on [Ca2+]i entry responses to TRPM8 or TRPA1 agonist with absence of CICR. Inhibition of HASMC response to WS-12 50 μM (a) or ASP 7663 50 μM (b) by ferulic acid (red symbols and line) or Z-ligustilide (blue symbols and line) with absence of CICR. Sigmoidal log concentration-response curve was drawn. Results were presented as a percentage of the peak [Ca2+]i entry level measured in the presence of 50 μM WS-12 or ASP 7663 50 μM. Each value was derived from 3 individual experiments with a total of 30–80 cells. HASMC were quiescent in serum-free medium for 24 hours before experiments.

3.1.3. Inhibition of WS-12 and ASP 7663 by the Drug Combination

The individual IC50 values for ferulic acid (8.318 ± 1.03 μM) and Z-ligustilide (7.839 ± 1.09 μM) were used to define four concentrations of the drugs in the combination at a fixed ratio for inhibition of WS-12, while ferulic acid (9.124 ± 1.04 μM) and Z-ligustilide (6.83 ± 1.12 μM) were used in the same way for inhibition of ASP 7663 (Table 1). Combination index was used to confirm the synergistic effect of ferulic acid with Z-ligustilide. The CI values were calculated by Calcusyn software to analyze the degree of drug interaction. Isobolograms and Fa values were provided to descript the inhibition rate at Figure 3 and Table 2. The CI values of <1 and >1 represented synergistic and antagonistic effect separately. Since all the CI values were <1, our results showed ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide having synergistic effect to inhibit [Ca2+]i release from HASMC exposing to TRPM8 agonist WS-12 or TRPA1 agonist ASP 7663.

Table 1.

Concentration of combination drug used in inhibiting [Ca2+]i response to agonists.

| Agonist | Ferulic acid (μM) | Z-ligustilide (μM) | Total concentration (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WS-12 | 2.1 | 2 | 4 |

| 4.2 | 3.9 | 8.1 | |

| 16.8 | 15.6 | 33.1 | |

| 33.4 | 31.3 | 64.7 | |

|

| |||

| ASP 7663 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 4 |

| 4.6 | 3.4 | 8 | |

| 18.3 | 13.7 | 32 | |

| 36.5 | 27.3 | 63.8 | |

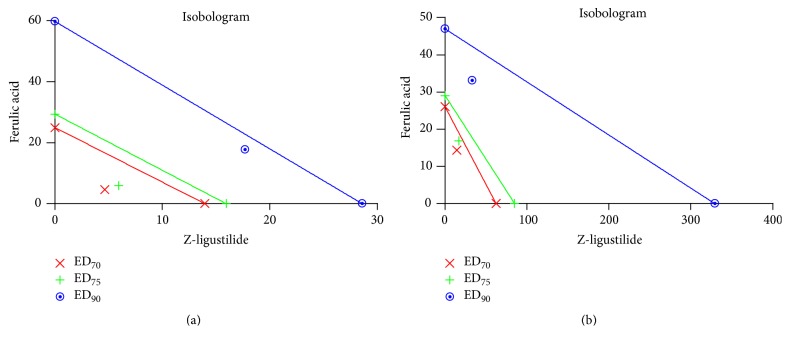

Figure 3.

Isobolograms of combination of ferulic acid with Z-ligustilide in inhibiting [Ca2+]i response to agonists. The individual doses of ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide to achieve 90% (straight line) inhibition (Fa = 0.90), 75% (hyphenated line) inhibition (Fa = 0.75), and 70% (crosses) inhibition (Fa = 0.70) were plotted on the x-axes and y-axes. Combination index (CI) values calculated by Calcusyn software are represented by points above (indicating antagonism) or below the lines (indicating synergism).

Table 2.

Combination index (CI) at ED70, ED75, and ED90 values with drug combination on inhibiting [Ca2+]i response to agonists. The CI values at Fa value of 0.70, 0.75, and 0.90 for isobolograms (Figure 3) were calculated with the Calcusyn version 2.1 software.

| ED70 | ED75 | ED90 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS-12 | FA : lig (8.3 : 7.8) | 0.16218 | 0.16971 | 0.22336 |

| ASP 7663 | FA : lig (9.1 : 6.8) | 0.26528 | 0.2655 | 0.2848 |

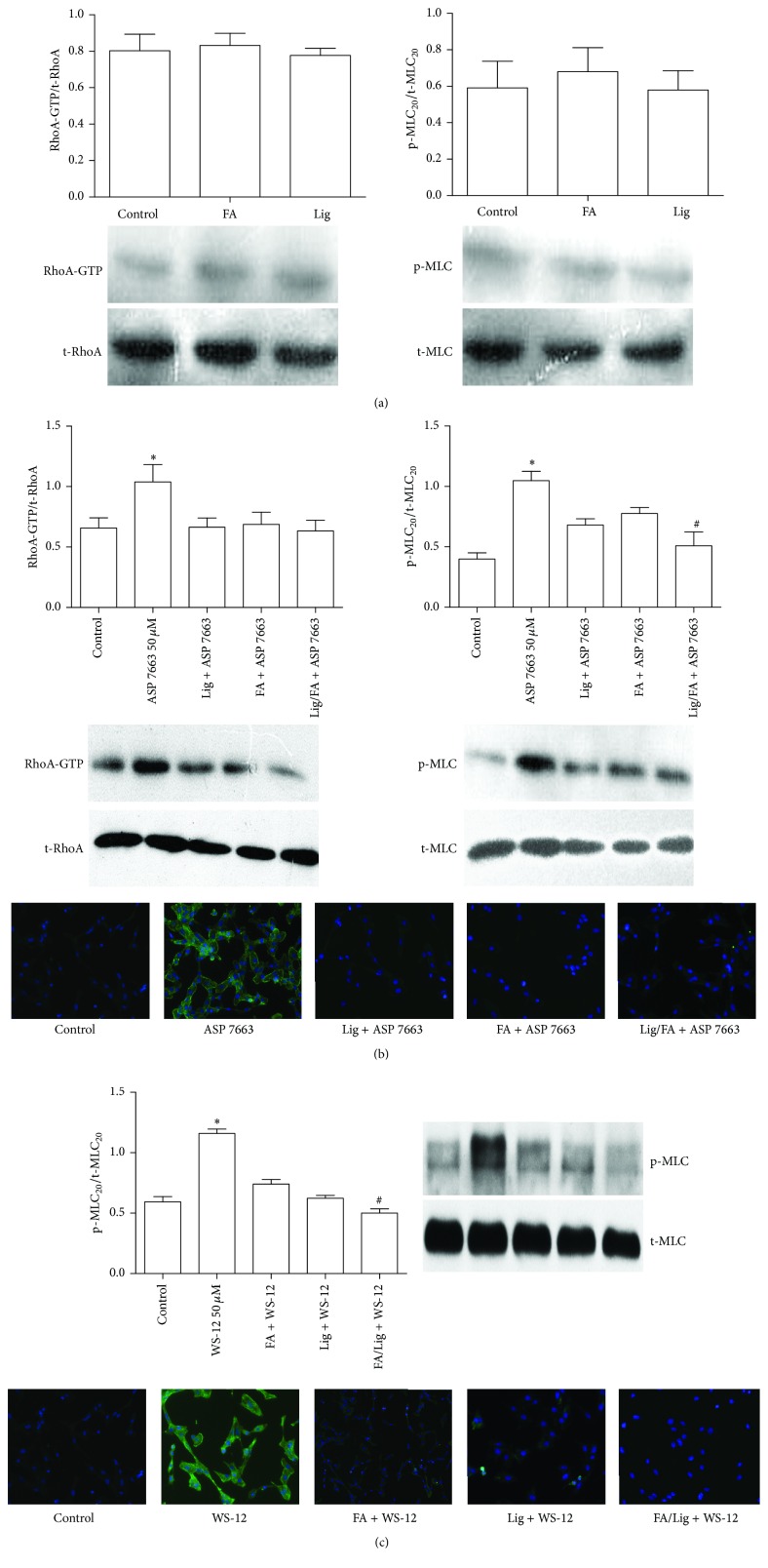

3.2. Responses to WS-12 or ASP 7663-Induced RhoA Activation and MLC20 Phosphorylation

To determine whether ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide may influence calcium sensitivity and eventually smooth muscle cell contraction, via TRPM8 channel or TRPA1 channel, HASMC were tested in the presence or absence of drugs for the occurrence of WS-12 or ASP 7663 induced RhoA activation and phosphorylation of MLC20 by Western blotting. Concentration of ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, and their combination was determined by IC50 obtained from experiment above. Ferulic acid or Z-ligustilide could activate neither RhoA nor phosphorylation of MCL20 in HASCM without any stimulation (Figure 4(a)). ASP 7663 treatment increased the GTP-RhoA level and phosphorylation of MLC20 signal, while ferulic acid (18 μM), Z-ligustilide (13 μM), and their combination (31 μM) could all decrease it (Figure 4(b)). WS-12 treatment could not increase GTP-RhoA level (Data not shown), while it could still increase phosphorylation of MLC20 signal. Ferulic acid (16 μM), Z-ligustilide (15 μM), and their combination (31 μM) can all decrease it (Figure 4(c)).

Figure 4.

Inhibition effects of ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, or their combination on GTP-RhoA level and phosphorylation of MLC20 with absence or presence of WS-12 or ASP 7663. HASMC were stimulated by ferulic acid or Z-ligustilide alone (a), 50 μM WS-12 (b), or 50 μM ASP 7663 (c) for 10 minutes in the absence or presence of ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, or their combination. Data are expressed in % of GTP-RhoA expression normalized to total RhoA expression or phosphorylation of MLC20 normalized to total MLC20 expression. Immunofluorescence images of phosphorylation of MLC20 were also captured. Bars are mean values from 3 individual samples. ∗Significant difference compared to control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference compared to ferulic acid group or Z-ligustilide group (P < 0.05).

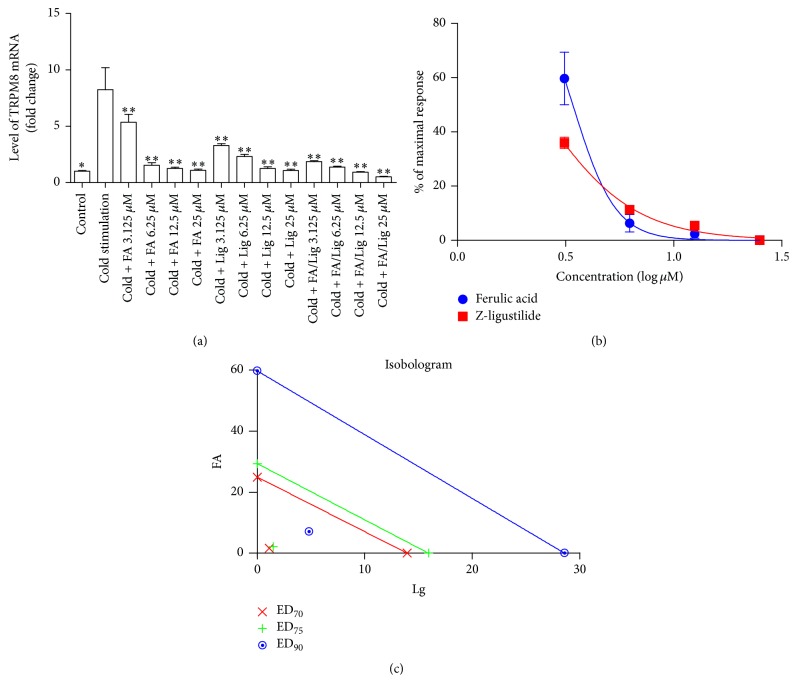

3.3. Response to Cold-Induced Upregulation of TRPM8 and TRPA1

Figure 5(a) showed higher gene expression of TRPM8 from HASMC incubating at 10°C (5% CO2) for 4 hours, when compared to control group. TRPA1 gene expression was not influenced by 10° (Data not shown). Different concentration of ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide could inhibit upregulation of TRPM8 mRNA expression (Figure 5(a)). The individual IC50 values (Figure 5(b)) of ferulic acid (3.416 ± 1.04 μM) and Z-ligustilide (2.325 ± 1.05 μM) were used to define four concentrations (Table 3) of the drugs in the combination at a fixed ratio for response to cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8. Isobolograms (Figure 5(c)) and CI values (Table 4) represented that ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide synergistically inhibited cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8 expression.

Figure 5.

Effect of ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, or their combination on cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8. (a) and (b) show effects of different concentration of ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide on inhibiting trpm8 gene expression. (c) shows isobolograms of combination of ferulic acid with Z-ligustilide. Combination index (CI) values calculated by Calcusyn software were all below points, which indicate synergism. ∗Significant difference between control group versus cold-stimulation group. ∗∗Significant difference between groups versus cold-stimulation group.

Table 3.

Concentration of single drugs and combination drug used in inhibiting cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8.

| Single drug (μM) | Combination drug (μM) | Total concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferulic acid | Z-ligustilide | Ferulic acid | Z-ligustilide | |

| 3.125 | 3.125 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 5.7 |

| 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.8 | 4.7 | 11.5 |

| 12.5 | 12.5 | 13.7 | 9.3 | 23 |

| 25 | 25 | 27.3 | 18.6 | 45.9 |

Table 4.

Combination index (CI) at ED70, ED75, and ED90 values with drug combination on inhibiting cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8 expression. The CI values at Fa value of 0.70, 0.75, and 0.90 for isobolograms (Figure 5(c)) were calculated.

| Drug (ratio) | CI values at | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ED70 | ED75 | ED90 | |

| FA : lig (3.416 : 2.325) | 0.14943 | 0.16879 | 0.28823 |

TRPM8 and TRPA1 ion channel have been improved to play an important role in processing pain, but the role in cardiovascular system is still controversial. Role of TRPM8 in mediating vasoconstriction and vascular tone is full of paradox. On the one hand, cold-induced vasoconstriction in hind paw was reduced in TRPM8 KO mice or in WT mice pretreated with TRPM8 antagonist AMTB [5]; meanwhile, cold-induced contraction of rat gastric fundus can be attenuated by TRPM8 antagonist as well as ROCK antagonist Y-27632 [20]. On the other hand, Johnson et al. [12] proved that TRPM8 nonspecific agonist menthol caused moderate contraction in relaxed tail artery, but relaxation of vessels precontracted with KCL or phenylephrine. It is possible that TRPM8 channel in sympathetic terminals can cause release of neurotransmitters, resulting in vasoconstriction under relaxed condition. Besides, TRPM8 may be activated in sensory axon collateral nerves which can release vasodilator substances such as calcitonin gene-related peptide [21]. As far as TRPA1 was concerned, activation of TRPA1 could induced either vasoconstriction accomplished by norepinephrine and ROS [5] or vasodilation induced by vasodilator substance released from sensory nerve [17, 22].

Our results showed that both TRPM8 specific agonist WS-12 and TRPA1 specific agonist ASP 7663 could extent phosphorylation of MLC20, that is, stimulated HASMC contraction directly. However, some differences of contraction mechanisms existed. TRPA1-induced contraction was achieved by calcium-dependent and calcium-sensitization way, while TRPM8-induced contraction was achieved mainly through calcium-dependent way. As far as CICR was concerned, activation of TRPM8 could induce calcium released from ryanodine receptor while TRPA1 could activate both ryanodine receptor and IP3 receptor.

In the last part, we discussed cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8 and TRPA1. Both oxaliplatin-induced acute cold-hypersensitivity model and chronic construction injury (CCI) model of neuropathic pain in rat were accompanied with upregulation of TRPM8 and TRPA1 expression in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [23–25]. Whether cold temperature can alter TRPM8 and TRPA1 expression in vascular system is still unknown. It is reported that phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in DRG appeared when the peripheral tissue was stimulated by cold temperature. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry proved that p-p38-IR neurons heavily colocalized with TRPA1, whereas the majority of p-ERK-IR neurons were positive for TRPM8 [26]. Cold-induced upregulation of p-ERK may contribute to upregulation of TRPM8. Our results indicated that cold stimulation could induce upregulation of TRPM8 but not TRPA1. In previous experiment, we discovered that amount of TRPA1 was much lesser than TPRM8 in human aortic smooth muscle cell. Expression of TRPA1 may not enough to be detected by qRT-PCR. Further investigation is needed.

A. sinensis has been used as a medical plant in numerous traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions for thousands of years. Previous studies showed that the effective constituents of A. sinensis extract could be classified into water-soluble parts and essential oil. One of the major constituents of water-soluble parts is ferulic acid, while Z-ligustilide has been reported as one of the major essential oil components [3, 4]. It is proved that Z-ligustilide can inhibit vasoconstriction induced by vasoconstrictors, such as norepinephrine and calcium chloride, on rat aortic segment. It may also protect ischemic brain injury in rats due to inhibiting the calcium influx through voltage-dependent calcium channel and receptor-mediated calcium [27]. Ferulic acid can induce concentration-dependence aorta vasodilation in chronic renal hypertensive rats [28]. It may also reduce carotid arterial pressure in anesthetized spontaneously hypertensive rats [29]. Synergistic inhibiting effect of these two components on calcium influx and combination inhibiting effect on RhoA-GTP induced by TRPM8 and TRPA1 agonist as well as synergistic inhibition on cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8 indicated that A. sinensis may attenuate, at least partially, vasoconstriction induced by cold-sensing channels TRPM8 and TRPA1.

4. Conclusion

Activation of TRPM8 and TRPA1 could induce contraction of human aortic smooth muscle cell via calcium influx and RhoA pathway. Cold temperature could upregulate TRPM8 expression. Synergistic effect on inhibiting calcium influx and cold-induced upregulation of TRPM8 by ferulic acid and Z-ligustilide was discovered.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81173189).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work; there are no professional or other personal interests of any nature or kind in any product, service, and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in the paper.

References

- 1.Chen D., Tang J., Khatibi N. H., et al. Treatment with Z-ligustilide, a component of Angelica sinensis, reduces brain injury after a subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;337(3):663–672. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.177055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu T. Clinical application of angelica sinensis. China's Naturopaty. 2015;9, article 55 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X.-P., Li W., Xiao X.-F., Zhang L.-L., Liu C.-X. Phytochemical and pharmacological studies on Radix Angelica sinensis . Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 2013;11(6):577–587. doi: 10.1016/s1875-5364(13)60067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma J.-P., Guo Z.-B., Jin L., Li Y.-D. Phytochemical progress made in investigations of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 2015;13(4):241–249. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(15)30010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aubdool A. A., Graepel R., Kodji X., et al. TRPA1 is essential for the vascular response to environmental cold exposure. Nature Communications. 2014;5, article no. 5732 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKemy D. D. How cold is it? TRPM8 and TRPA1 in the molecular logic of cold sensation. Molecular Pain. 2005;1, article 16 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Premkumar L. S., Abooj M. TRP channels and analgesia. Life Sciences. 2013;92(8-9):415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspani O., Zurborg S., Labuz D., Heppenstall P. A. The contribution of TRPM8 and TRPA1 channels to cold allodynia and neuropathic pain. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007383.e7383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentry C., Stoakley N., Andersson D. A., Bevan S. The roles of iPLA2, TRPM8 and TRPA1 in chemically induced cold hypersensitivity. Molecular Pain. 2010;6, article 4 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X.-R., Lin M.-J., McIntosh L. S., Sham J. S. K. Functional expression of transient receptor potential melastatin- and vanilloid-related channels in pulmonary arterial and aortic smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology—Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2006;290(6):L1267–L1276. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00515.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun J., Yang T., Wang P., et al. Activation of cold-sensing transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8 antagonizes vasoconstriction and hypertension through attenuating RhoA/Rho kinase pathway. Hypertension. 2014;63(6):1354–1363. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.02573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson C. D., Melanaphy D., Purse A., Stokesberry S. A., Dickson P., Zholos A. V. Transient receptor potential melastatin 8 channel involvement in the regulation of vascular tone. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2009;296(6):H1868–H1877. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01112.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daanen H. A. M. Finger cold-induced vasodilation: a review. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;89(5):411–426. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson J. M., Yen T. C., Zhao K., Kosiba W. A. Sympathetic, sensory, and nonneuronal contributions to the cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to local cooling. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;288(4):H1573–H1579. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00849.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson J. M., Minson C. T., Kellogg D. L., Jr. Cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor mechanisms in temperature regulation. Comprehensive Physiology. 2014;4(1):33–89. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynne B. M., Chiao C.-W., Webb R. C. Vascular smooth muscle cell signaling mechanisms for contraction to angiotensin II and endothelin-1. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension. 2009;3(2):84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pozsgai G., Bodkin J. V., Graepel R., Bevan S., Andersson D. A., Brain S. D. Evidence for the pathophysiological relevance of TRPA1 receptors in the cardiovascular system in vivo . Cardiovascular Research. 2010;87(4):760–768. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou T.-C., Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L., Wientjes M. G., Au J. L.-S. Evaluation of combination chemotherapy: integration of nonlinear regression, curve shift, isobologram, and combination index analyses. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(23):7994–8004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-04-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustafa S., Oriowo M. A. Cooling-induced contraction of the rat gastric fundus: Mediation via Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) cation channel TRPM8 receptor and Rho-kinase activation. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2005;32(10):832–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu S., Wang Y., Pan L., et al. Involvement of transient receptor potential melastatin-8 (TRPM8) in menthol-induced calcium entry, reactive oxygen species production and cell death in rheumatoid arthritis rat synovial fibroblasts. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;725(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graepel R., Fernandes E. S., Aubdool A. A., Andersson D. A., Bevan S., Brain S. D. 4-Oxo-2-nonenal (4-ONE): evidence of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1-dependent and -independent nociceptive and vasoactive responses in vivo. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;337(1):117–124. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nassini R., Gees M., Harrison S., et al. Oxaliplatin elicits mechanical and cold allodynia in rodents via TRPA1 receptor stimulation. Pain. 2011;152(7):1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frederick J., Buck M. E., Matson D. J., Cortright D. N. Increased TRPA1, TRPM8, and TRPV2 expression in dorsal root ganglia by nerve injury. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;358(4):1058–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakurai M., Egashira N., Kawashiri T., Yano T., Ikesue H., Oishi R. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy in the rat: involvement of oxalate in cold hyperalgesia but not mechanical allodynia. Pain. 2009;147(1–3):165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizushima T., Obata K., Katsura H., et al. Noxious cold stimulation induces mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in transient receptor potential (TRP) channels TRPA1- and TRPM8-containing small sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;140(4):1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J.-Y., Chen H.-H., Wu J., et al. Advances in studies on pharmacological functions of ligustilide and their mechanisms. Chinese Herbal Medicines. 2012;4(1):26–32. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-6384.2012.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi S., Kim H. I., Park S. H., et al. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation by ferulic acid in aorta from chronic renal hypertensive rats. Kidney Research and Clinical Practice. 2012;31(4):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki A., Kagawa D., Fujii A., Ochiai R., Tokimitsu I., Saito I. Short- and long-term effects of ferulic acid on blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. American Journal of Hypertension. 2002;15(4):351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]