Abstract

This study aimed to investigate whether ultrasound-induced microbubble destruction was able to promote targeted delivery of adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) to improve hind-limb ischemia of diabetic mice. Ischemia was induced in the lower limb of db/db mice which were then randomly divided into 5 groups: PBS group, Sham group, ultrasound + microbubble group (US+MB), US+MB+ASCs group and ASCs group. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound perfusion imaging showed the ratio of blood flow in ischemic hind-limb to that in contralateral limb increased over time in five groups. A significant enhancement in US+MB+ASCs group was observed compared with US+MB group (P<0.01). Immunofluorescence microscopy of hind-limb muscle showed the microvessel density (microvessels/skeletal muscle fibers) and arteriolar density in US+MB+ASCs group were higher than in US+MB group, and significantly higher than in other control groups (P<0.01). Masson staining indicated the degree of muscle fibrosis in US+MB+ASCs group was lower than in US+MB. 3 and 7 days after therapy, ELISA and RT-PCR showed the expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was higher than in US+MB group, and dramatically increased as compared to other groups (P<0.01). 3 and 7 days after therapy, Western blot assay showed the protein expression of P-P13K, P-AKT, VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was higher than US+MB group (P<0.01). The bioeffects of ultrasound-induced microbubble cavitation is able to up-regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may improve the targeted delivery, adhesion and paracrine of ASCs, attenuating the hind-limb ischemia in diabetic mice.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, ultrasound examination, microbubble, stem cells, diabetes mellitus, hind-limb ischemia

Introduction

Diabetic peripheral artery disease (PAD) is one of severe chronic complications of diabetic mellitus (DM) and an important cause of disability and mortality, which significantly affects the quality of life of patients [1,2]. Therapeutic angiogenesis provides a new method for the therapy of ischemic vascular diseases. In recent years, the stem cells transplantation becomes a promising strategy for the therapy of DM and its complications. Adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) have been regarded an ideal source of stem cells in the regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. There is evidence showing that the lower limb ischemia is significantly improved 3 weeks after local injection of ASCs in the ischemic lower limb of mice (increases in blood flow and microvessel density) [3]. However, in case of DM, the majority of transplanted stem cells will become apoptotic or necrotic due to some factors such as hyperglycemia, hypoxia and nutrient deficiency, and the residual stem cells are not enough to secret sufficient pro-angiogenic factors for the improvement of diabetic PAD. Thus, to improve the viability of transplanted stem cells has been a challenge in the treatment of DM and its complications by stem cell transplantation. Ultrasound-induced microbubble destruction as a new and promising therapeutic strategy has been widely in some fields. It may transport genes or drugs to a specific tissue and promote the targeted delivery of stem cells [4-8]. Some investigators attempted to treat lower limb ischemia via targeted delivery of bone marrow mononuclear cells by ultrasound destruction of microbubbles, and results showed ultrasound destruction of microbubbles could increase the targeted adhesion of MSCs, elevate targeted delivery of MSCs to the ischemic lower limb, exerting better therapeutic effects on lower limb ischemia. However, whether this technique is still effective in case of DM is still unclear, and few studies have been conducted to investigate this issue. This study aimed to investigate the ASCs therapy of lower limb ischemia in the presence of ultrasound-induced microbubble destruction and to explore the potential mechanism.

Materials and methods

Materials

ASCs were purchased from Guangzhou Cyagen Biosciences Inc. ASCs were thawed for further use. ASCs at 1×106/ml in 0.1 ml of PBS were injected via the tail vein. SonoVue ultrasound contrast agent (Bracco) was mixed with 5 ml of normal saline before use. The mean diameter of microbubbles was 2.5 μm and their mean concentration was 5×108/ml. Therapeutic Portable Ultrasound Device (PHYSIOSON Expert; PHYSIOMED, Germany) and MYTWICE instrument (Esaote, Italy) were used in this study.

Preparation of animals

Male db/db mice aged 8-10 weeks were purchased from Nanjing Model Experimental Animal Center. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji University. Mice received food deprivation for 12 h before surgery, but were given ad libitum access to water. The hair on the right lower limb was removed, and mice were then anesthetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital at 30 mg/kg (i.p.). Mice were placed on a surgery table and the surgical site was disinfected. An incision was made from the middle of the knee of right low limb to the inguinal ligament. The fascias and muscles were sequentially separated, and hemostasis was done by pressurization. The femoral vein and artery were separated under a microscope, and both were ligated at the distal end of the iliac artery bifurcation at two sites and then cut between them. In sham group, the artery and vein were separated, but not ligated. The wound was closed, and buprenorphine hydrochloride was used after surgery for pain relief. 3 days after surgery, mice were randomly assigned into 5 groups: (1) PBS group: mice were injected with 0.1 ml of PBS via the tail vein (n=24); (2) sham group (n=24); (3) ultrasound + microbubble group (US+MB): mice were injected with 0.1 ml of SonoVue, ultrasound was used for 2 min (n=23); (4) US+MB+ASCs group: mice were injected with 0.1 ml of SonoVue and then with 1×106/ml ASCs in 0.1 ml of PBS within 2 min, ultrasound was used for 2 min (n=24); (5) ASCs group: mice were injected with 1×106/ml ASCs in 0.1 ml of PBS via the tail vein (n=23). The coupling agent was smeared at the right ischemic muscle, the frequency of probe was 1 MHz, the sound intensity was 2 W/cm2, duty cycle was 20%, and ultrasound was used for 2 min. The mean concentration of ultrasound contrast agent was 5×108/ml.

Ultrasound contrast perfusion imaging

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS; MYTWICE instrument, Italy) was performed with LA523 probe with the frequency of 7-13 MHz and mechanical index of 0.05, DP 45 kPa. Mice were intraperitoneally anethetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital at 30 mg/kg and then placed on a surgery table. The coupling agent was smeared on the proximal adductor of right lower limb and the optimal image was acquired by moving the location of the probe. Then, the limb and probe were maintained at a fixed position. Microbubbles were injeccted via the tail vein at 5×107/min. When the skeletal filling at imaging reached a maximal intensity, FLASH was administered to disrupt the microbubbles. Then, images were captured. Ultrasound was administered until maximal intesity was obtained at the skeletal muscle. The video of the whole imaging was stored in a disc for analysis off-line. The region of interest was selected, and the time-intensity curve was delineated with QontraXt software. A was calculated as follow: A = maximal intensity of perfusion signals, β = reperfusion rate. The injection speed of contrast agent was maintained constant, and thus there was a close relationship between image intensity and amount of local microbubbles which could be determined with a function [9]: y=A*(1-e-βt). The triggering time interval - intensity curve of the region of interest was delineated and the values of A, β and A*β were calculated independently. The maximal amount of accumulated microbubbles (A) reflects the local microvessel density (MVD), but the local filling rate (β) reflects the local blood flow rate of the skeletal muscle. The product of A and β (A*β) reflects the local blood flow. The ratio of A*β at ischemic limb to that at contralateral limb was calculated as the degree of lower limb ischemia.

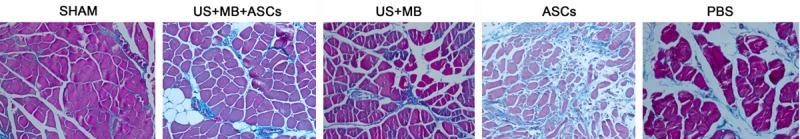

Masson staining

14 days after therapy, right lower limb gracilis muscle, abductor pollicis longus and gastrocnemius was collected, embedded in paraffin and then deparaffinized, followed by Masson staining for the observation of muscle fibrosis.

Immunofluorescence staining and immunohistochemistry

14 days after treatment, the right lower limb gracilis muscle, abductor pollicis longus and gastrocnemius was collected and embedded in paraffin for immunofluorescence staining and immunohistochemistry according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary antibodies (rabbit anti-human smooth musele a-actin [a-SMA] polyclonal antibody; Abeam, UK; Biotin conjugated Bandeiraea Simplieifolia-1lectin; Sigma, Germany), and secondary antibody (DAKO) were used. Different fields were selected from the section of animals sacrificed at different time points, and the amount of micrvessels and muscle fibers was determined to calculate the MVD. At different time points, sections were prepared for the detection of arteriole number at a high magnification as the arteriolar density.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

3 and 7 days after treatment, blood was collected and plasma was harvested after centrifugation. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed to detect the contents of ICAM-1, P-selectin, SDF-1 and VEGF accoring to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent and reversely transcribed into cDNA with Revert AIDTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis (TAKARA, JAPAN). Real time fluorescence PCR was conducted with 7500 theramal cycler under following conditions: 95°C for 30 s, 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s for a total of 45 cycles. Expertiment was performed three times. The mRNA expression of ICAM-1, P-selectin, SDF-1 and VEGF was detected by PCR with GAPDH as an internal reference. Primers were synthesized in BGI Biotech Co., Ltd.

Western blot assay

3 and 7 days after treatment, the right lower limb gracilis muscle, abductor pollicis longus and gastrocnemius was collected for the detection of P-Akt, T-Akt, PI3K, P-PI3K, ICAM-1, P-selectin, VEGF and SDF-1. In brief, 100 mg of skeletal muscle was lysed in 0.5 ml of RIPA lysis buffer for 5 min at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 12000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined with BCA protein concentration assay kit. The supernatant was stored at -80°C. Proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 5% stacking gel at 80 V for 30 min and then 8% separating gel at 11 V for 100 min. Then, the proteins were electrotransferred onto PVDF membrane at 0.25 A for 3 h at 4°C, which was blocked with 7% BSA-TBST (25 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with TBST thrice, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody in 5% BSA-TBST at 4°C for 12 h. Following washing in TBST 4 times (15 min for wach), the membrane was treated with HRP conjugated secondary antibody in 5% BSA-TBST for 1 h at room temperature. After washing in TBST 4 times (15 min for each), visualization was performed thrice (5 min for each). The optical density (OD) of protein bands was determined with Image J software as the protein expression. The OD of target gene was normalized to that of GAPDH as the relative protein expression of target gene.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 19.0. Qualitative data were compared with chi square test, and quantitative data with one way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni test. A value of twosided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

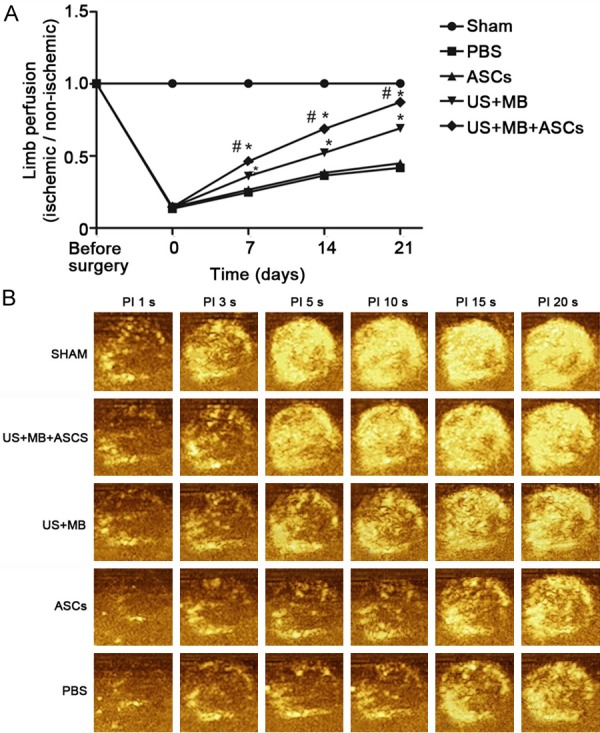

Effects of US+MB+ASCs-i.v. on blood flow recovery in ischemic hind-limb in db/db mice

Ultrasound contrast perfusion imaging was performed before surgery and immediately, 7 days, 14 days and 21 days after treatment to evaluate the blood perfusion in the ischemic limb. Before surgery, the blood perfusion was similar among groups. After ischemia, the blood perfusion increased gradually over time (Figure 1A). Intravenous injection of ASCs (ASCs-i.v.) did not cause a significant increase in the blood flow recover compared with the PBS group. Treatment with US+MB without ASCs-i.v. showed a moderate increase (69±3% on day 21 versus PBS, P<0.01), whereas the combination of US+MB and ASCs-i.v. induced a further increase (87±2% versus PBS on day 21, P<0.01), which was significantly higher than that of ASCs-i.v. alone (P<0.01), suggesting that the US+MB+ASCs significantly improves the blood flow recovery after limb ischemia compared with other groups, and that the efficient cell delivery system depends on US mediated destruction of microbubbles. The blood flow in ischemic limb on day 21 is shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Proximal hindlimb contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) perfusion data in all groups. A. The ratio of blood flow in ischemic limb to that in contralateral limb for the all groups; at baseline and immediately, 7, 14 and 21 days after treatment, the US+MB+ASCs groups induced a further increase versus to other groups on Day 7, 4 and 21, (*P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB). B. Representative CEU-perfusion images of ischemic hindlimb muscle blood flow from all groups on day 21 after treatment. CEU signal from microbubbles was greatest for US+MB+ASCs groups (other than SHAM groups).

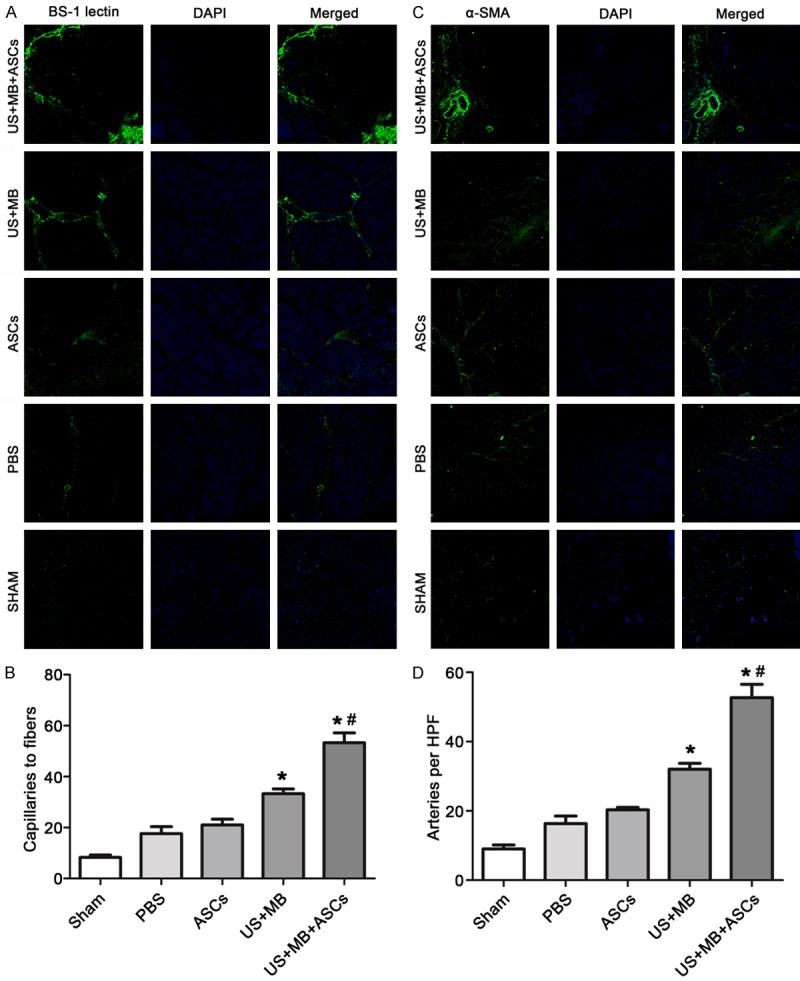

Effects of US+MB+ASCs-i.v. on capillary density in ischemic hind-limbs in db/db mice

In this study, we also measured the capillary density in histological sections harvested from the ischemic tissues. Immunofluorescence staining was performed for BS-1 and α-SMA to evaluate the angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Representative photomicrographs are shown in Figure 2A and 2C. Quantitative analysis revealed that the MVD (microvessels/fibers in skeletal muscle) on day 14 at the ischemic skeletal muscles was significantly greater in the US+MB+ASCs group compared to the other 4 groups (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB; Figure 2B). Again MVD in the US+MB group was higher as compared to the PBS group (P<0.01, Figure 2B). 14 days after therapy, the arteriole density (number of arteriole per high field) in US+MB+ASCs group increased significantly as compared to the other 4 groups (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB; Figure 2D), and the arteriole density in the US+MB group was higher as compared to the PBS group (P<0.01, Figure 2D). These findings suggest that US+MB+ASCs group enhances both angiogenesis as well as arteriogenesis response.

Figure 2.

Capillary and arteriolar density of ischemic hindlimb muscle on day 14 after treatment from all groups by Immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence staining was performed for BS-1 and α-SMA to evaluate the angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Representative color-coded images of capillary density (A) and arteriolar (C) from hindlimb skeletal muscle in all groups on day 14. MVD (microvessels/fibers in skeletal muscle) on day 14 at the ischemic skeletal muscles was significantly greater in the US+MB+ASCs group compared to the other 4 groups (*P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB) (B). The arteriole density (number of arteriole per high field) in US+MB+ASCs group increased significantly as compared to the other 4 groups. *P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB (D).

Masson’s staining imaging illustrates absence of significant fibrosis in US+MB+ASCs group

14 days after therapy, Masson staining showed the amount of muscle fibers in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly lower than in other groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

14 days after therapy, Masson staining showed the amount of muscle fibers in US+MB+ASCs group was markedly lower than in other groups (other than SHAM groups).

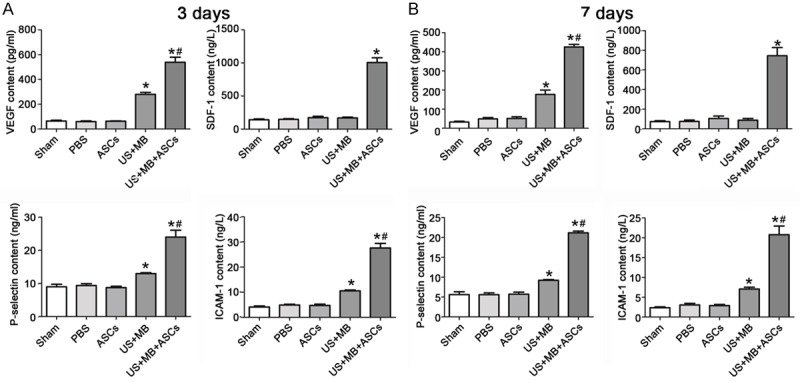

Effects of US+MB+ASCs-i.v. on contents of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in db/db Mice

We next examined the contents of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 by ELISA. 3 days after treatment, the contents of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than in the other 4 groups (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB; Figure 4A), and that in US+MB group was higher than PBS groups (P<0.01). The SDF-1 content on day 3 was the highest in US+MB+ASCs group as compared to other groups (P<0.01 vs PBS) (Figure 4A). 7 days after treatment, the contents of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 on day 7 was lower than on day 3, the contents of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly greater than in other groups (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB; Figure 4B), and that in US+MB group was higher than in PBS groups (P<0.01). In addition, SDF-1 content on day 7 was lower than on day 3, and significant difference was observed between US+MB+ASCs group and PBS group (P<0.01, Figure 4B). However the contents of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in ASCs group was not significantly different from that of PBS on day 3 and 7.

Figure 4.

The contents of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 by ELISA. A. 3 days after treatment, the contents of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was dramatically higher than in other group,*P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB. B. The contents of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 on day 7 was lower than on day 3, *P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB.

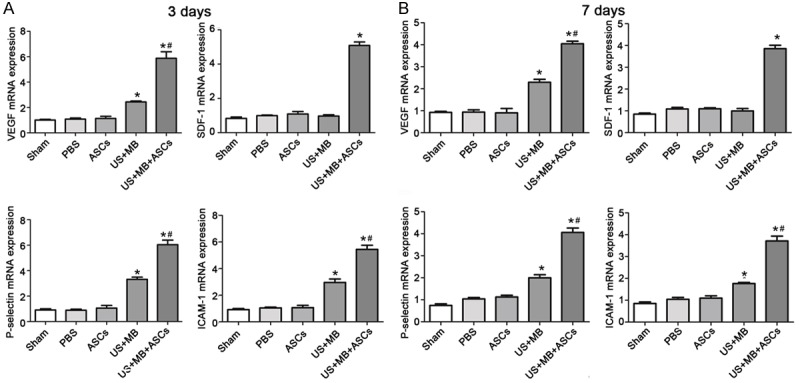

Effects of US+MB+ASCs-i.v. on mRNAs expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in ischemic hind-limb in db/db mice

We examined the expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 mRNAs by real-time RT-PCR. 3 days after treatment, the mRNA expression of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than in other group (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB; Figure 5A), and that in US+MB group was significantly higher than in PBS groups (P<0.01). The SDF-1 mRNA expression on day 3 was the highest in US+MB+ASCs group (P<0.01 vs PBS, Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

The expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 mRNAs by real-time RT-PCR. A. 3 days after treatment, the mRNA expression of VEGF, P-selectin , ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was dramatically higher than in other group, *P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB. B. 7 days after treatment, the expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 mRNAs on day 7 was lower than on day 3, *P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB.

7 days after treatment, the mRNA expression of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 in US+MB+ASCs group increased as compared to other groups (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB; Figure 5B), and that in US+MB group was higher than in PBS groups (P<0.01). The SDF-1 mRNA expression on day 7 reduced as compared to that on day 3. The SDF-1 mRNA expression in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than that in other groups (P<0.01, Figure 5B). But the mRNA expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and SDF-1 in ASCs group was not significantly different from that of PBS on day 3 and 7.

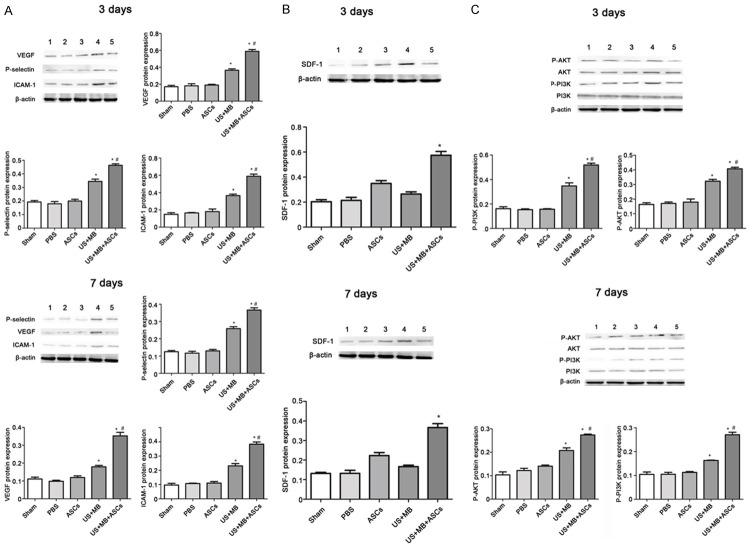

Effects of US+MB+ASCs-i.v. on protein expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1, SDF-1, P-Akt and P-PI3K in ischemic hind-limb in db/db mice

3 days after therapy, the protein expression of VEGF, P-selectin, ICAM-1, P-Akt and P-PI3K in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly different from that in other groups, and that in US+MB group was higher than in PBS groups; 7 days after treatment, the protein expression of those reduced in the ischemic muscle as compared to that on day 3. The protein expression of P-selectin, ICAM-1, P-Akt and P-PI3K in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than that in other groups (P<0.01 versus PBS and US+MB, Figure 6A, 6C). 3 days after therapy, the protein expression of SDF-1 was the highest in US+MB+ASCs group, The SDF-1 mRNA expression on day 7 reduced as compared to that on day 3, and it in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than that in other groups (P<0.01 versus PBS; Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis and quantitative data. A. 3 days after therapy, the protein expression of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly different from that in other groups, and the protein expression of VEGF, P-selectin and ICAM-1 on day 7 was lower than on day 3, (*P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB). B. 3 days after therapy, the protein expression of SDF-1 in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly different from that in other groups, and the protein expression of SDF-1 on day 7 was lower than on day 3 (*P<0.01 compared with PBS). C. 3 days after therapy, the protein expression of P-Akt and P-PI3K in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly different from that in other groups, the protein expression of P-Akt and P-PI3K on day 7 was lower than on day 3, (*P<0.01 compared with PBS, and #P<0.01 compared with US+MB).

Discussion

Our study found that ultrasound induced microbubble destruction could increase the survival rate of ASCs in the ischemic limb and effectively promote the angiogenesis in the ischemic limb of diabetic mice. This may be related to the ultrasound induced mild injury to the endothelial cells of capillaries and the subsequent transient inflammation of endothelial cells, leading to the endothelial activation, elevated expression of P-selectin and ICAM-1 and the increased targeted delivery and adhesion of ASCs. In addition, the transplanted ASCs may secrete VEGF and SDF-1, which increases the differentiation of ASCs into vascular endothelial cells; the ultrasound induced up-regulation of VEGF expression also promotes the angiogenesis in the ischemic limb; VEGF may activate PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to further promote cell proliferation and inhibit cell apoptosis.

Ultrasound contrast perfusion imaging has been used to evaluate the microvascular perfusion in animal models of ischemia related disease [10,11]. In this study, results showed the ratio of blood flow in ischemic limb to that in contralateral limb [12] increased over time, and this increase was the most evident in US+MB+ASCs group. Immunohistochemistry showed the MVD and amount of arterioles in US+MB+ASCs group were significantly higher than in other groups. This suggests that US+MB may elevate angiogenesis and formation of arterioles to promote the blood perfusion recovery in US+MB+ASCs, which is consistent with findings from the study of Imada et al [13]. In addition, Masson staining showed the fibrosis was the mildest in US+MB+ASCs group. This confirms that angiogenesis and blood vessel formation are able to significantly improve the lower limb ischemia, reduce interstitial fibrosis, facilitate tissue repair.

In the present study, results showed the expression of P-selectin and ICAM-1 in US+MB+ASCs group and US+MB group was significantly higher than in PBS group and ASCs group, which was consistent with previosuly reported [13,14]. Some investigators have proposed that the ultrasound induced microbubble destruction is ascribed to the cavitation. Microbubbels may serve as effective cavitation nuclei [15] and the ultrasound induced microbubble cavitation may cause mechanical interference with adjacent cells and tissues, exerting bioeffects [16]. These effects may induce microvessel leakage, capillary rupture, cell death and inflammation [17]. In this study, the expression of P-selection and ICAM-1 increased significantly at protein and mRNA levels. Thus, we speculate that ultrasound induced microbubble cavitation may induce the transient inflammation of endothelial cells, leading to their activation. This may then up-regulate the expression of P-selectin and ICAM-1, which changes the microenvironment, promotes the targeted delivery and adhesion of stem cells and improves the migration of stem cells to targeted tissues. Thus, the number of transplanted ASCs crossing the capillaries in the interstitium increases. These findings were consistent with those reported by Zhong et al [18] and Ryu et al [10].

Although a variety of studies have been conducted to investigate the therapeutic effects of stem cells on tissue injury, the specific mechanism is still poorly understood [19-21]. Some investigators propose that stem cells can directly differentiate into target cells and then proliferate in the injured site, leading to the repair of injured tissues, angiogenesis and tissue regeneration. In addition, some investigators speculate that the tissue repair and angiogenesis following stem cells transplantation are related to the paracrine of stem cells. Studies have confirmed that ASCs can secret a lot of cytokines by paracrine [22,23], including VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor and SDF-1 [24], which is closely related to the vascular reconstruction. VEGF has been regarded as a cytokine closely associated with angiogenesis. VEGF may stimulate the differentiation of stem cells into endothelial cells and the proliferation of endothelial cells, leading to the angiogenesis [25-27]. Our results showed the mRNA and protein expressions of VEGF in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than in US+MB group and other groups. Moreover, VEGF expression in US+MB group was significantly higher than in ASCs group and PBS group. Thus, the ultrasound in the presence of microbubble may cause damage to the microvessels due to the mechanical and cavitation effects, leading to the secretion of endogenous VEGF [28,29] besides the VEGF secreted by stem cells [4], which may improve the angiogenesis and the lower limb ischemia.

ASCs may also secret another chemokine SDF-1 [3], which may induce the target migration of stem cells. In addition, SDF-1 may also promote the adhesion of stem cells [30]. Once stem cells arrive in the target organ, they may promote the angiogenesis and induce the formation of microvessles in the ischemic tissues [31]. In the present study, results showed SDF-1 expression in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than in ASCs group. Intravenous injection of ASCs may distribute stem cells in the whole body, suggesting a poor target delivery of stem cells. Under this condition, stem cells may not effectively localize in the ischemic skeletal muscle. Thus, few stem cells are involved in the repair of injured tissues, leading to a poor therapeutic efficacy in clinical practice [13]. The bioeffects of ultrasound may promote the targeted delivery of ASCs to the injured site. Under this condition, more stem cells migrate to the injured site where they secret more SDF-1. In addition, SDF-1 expression in US+MB group was relatively lower, suggesting that ultradound have no synergistic effect on SDF-1.

It has been confirmed that PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is one of important pathways involved in the bioeffects of VEGF [32,33] and crucial for the angiogenesis. VEGF may activate PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to block the apoptosis of endothelial cells. In addition, the activation of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway may also activate endothelium nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), leading to the production of NO and angiogenesis [34]. Thus, AKT is a key molecule in the angiogenesis. Our results showed the expression of P-AKT and P-PI3K in US+MB+ASCs group was significantly higher than in other groups, and the protein and mRNA expression of VEGF in US+MB+ASCs groups was also significantly higher than in other groups. Thus, we postulate that the increase in VEGF activate PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and the phosphorylated AKT may further activate or inhibit downstream proteins, which is able to regulate the cell proliferation and migration as well as the cell apoptosis [33,35].

There were still limitations in this study. The survived ASCs were not dynamically observed in vivo; VEGF neutrolization was not employed to further investigate the role of VEGF in the improvement of lower limb ischemia following ultrasound induced microbubble destruction.

Taken together, ultrasound induced microbubble destruction may increase the capillary permeability and up-regulate the expression of P-selectin and ICAM-1, leading to the elevated targeted delivery and adhesion of ASCs. In addition, the transplanted ASCs may secret VEGF and SDF-1 via paracrine, leading to their differentiation into endothelial cells. Moreover, ultrasound in the presence of microbubbles may also up-regulate VEGF expression, leading to the angiogenesis in ischemic limb. The VEGF may activate PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which regulates the cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Capacity Building Project of Clinical Ancillary Departments (SHDC: 22015009).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Forsythe RO, Hinchliffe RJ. Management of peripheral arterial disease and the diabetic foot. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2014;55:195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park B, Hoffman A, Yang Y, Yan J, Tie G, Bagshahi H, Nowicki PT, Messina LM. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase affects both early and late collateral arterial adaptation and blood flow recovery after induction of hind limb ischemia in mice. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo K, Shintani S, Shibata R, Murakami H, Murakami R, Imaizumi M, Kitagawa Y, Murohara T. Implantation of adipose-derived regenerative cells enhances ischemia-induced angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:61–66. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu YL, Gao YH, Liu Z, Tan KB, Hua X, Fang ZQ, Wang YL, Wang YJ, Xia HM, Zhuo ZX. Myocardium-targeted transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells by diagnostic ultrasound-mediated microbubble destruction improves cardiac function in myocardial infarction of New Zealand rabbits. Int J Cardiol. 2010;138:182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pompilio G, Capogrossi MC, Pesce M, Alamanni F, DiCampli C, Achilli F, Germani A, Biglioli P. Endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular homeostasis: clinical implications. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J, Qi M, Kaul S, Price RJ. Stimulation of arteriogenesis in skeletal muscle by microbubble destruction with ultrasound. Circulation. 2002;106:1550–1555. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028810.33423.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiessling F, Fokong S, Koczera P, Lederle W, Lammers T. Ultrasound microbubbles for molecular diagnosis, therapy, and theranostics. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:345–348. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Yao D, Ma J, Zhu J, Xu X, Ren Y, Ding X, Mao X. Transplantation of MSCs in combination with netrin-1 improves neoangiogenesis in a rat model of hind limb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2011;166:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation. 1998;97:473–483. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu JC, Davidson BP, Xie A, Qi Y, Zha D, Belcik JT, Caplan ES, Woda JM, Hedrick CC, Hanna RN, Lehman N, Zhao Y, Ting A, Lindner JR. Molecular imaging of the paracrine proangiogenic effects of progenitor cell therapy in limb ischemia. Circulation. 2013;127:710–719. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leong-Poi H, Kuliszewski MA, Lekas M, Sibbald M, Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Klibanov AL, Stewart DJ, Lindner JR. Therapeutic arteriogenesis by ultrasound-mediated VEGF165 plasmid gene delivery to chronically ischemic skeletal muscle. Circ Res. 2007;101:295–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan Y, Shao H, Eton D, Yang Z, Alonso-Diaz L, Zhang H, Schulick A, Livingstone AS, Yu H. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 enhances pro-angiogenic effect of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imada T, Tatsumi T, Mori Y, Nishiue T, Yoshida M, Masaki H, Okigaki M, Kojima H, Nozawa Y, Nishiwaki Y, Nitta N, Iwasaka T, Matsubara H. Targeted delivery of bone marrow mononuclear cells by ultrasound destruction of microbubbles induces both angiogenesis and arteriogenesis response. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2128–2134. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000179768.06206.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heil M, Schaper W. Influence of mechanical, cellular, and molecular factors on collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis) Circ Res. 2004;95:449–458. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141145.78900.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Zhang P, Liu P, Zhao Y, Gao S, Tan K, Liu Z. Endothelial adhesion of targeted microbubbles in both small and great vessels using ultrasound radiation force. Mol Imaging. 2012;11:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller DL, Averkiou MA, Brayman AA, Everbach EC, Holland CK, Wible JH Jr, Wu J. Bioeffects considerations for diagnostic ultrasound contrast agents. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:611–632. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.4.611. quiz 633-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zha Z, Wang S, Zhang S, Qu E, Ke H, Wang J, Dai Z. Targeted delivery of CuS nanoparticles through ultrasound image-guided microbubble destruction for efficient photothermal therapy. Nanoscale. 2013;5:3216–3219. doi: 10.1039/c3nr00541k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong S, Shu S, Wang Z, Luo J, Zhong W, Ran H, Zheng Y, Yin Y, Ling Z. Enhanced homing of mesenchymal stem cells to the ischemic myocardium by ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction. Ultrasonics. 2012;52:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stastna M, Abraham MR, Van Eyk JE. Cardiac stem/progenitor cells, secreted proteins, and proteomics. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1800–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tillmanns J, Rota M, Hosoda T, Misao Y, Esposito G, Gonzalez A, Vitale S, Parolin C, Yasuzawa-Amano S, Muraski J, De Angelis A, Lecapitaine N, Siggins RW, Loredo M, Bearzi C, Bolli R, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Formation of large coronary arteries by cardiac progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1668–1673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706315105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuda K, Falkenberg KJ, Woods AA, Choi YS, Morrison WA, Dilley RJ. Adipose-derived stem cells promote angiogenesis and tissue formation for in vivo tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1327–1335. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon KM, Park YH, Lee JS, Chae YB, Kim MM, Kim DS, Kim BW, Nam SW, Lee JH. The effect of secretory factors of adipose-derived stem cells on human keratinocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:1239–1257. doi: 10.3390/ijms13011239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung H, Kim HH, Lee DH, Hwang YS, Yang HC, Park JC. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 in adipose derived stem cells conditioned medium is a dominant paracrine mediator determines hyaluronic acid and collagen expression profile. Cytotechnology. 2011;63:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s10616-010-9327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figeac F, Lesault PF, Le Coz O, Damy T, Souktani R, Trebeau C, Schmitt A, Ribot J, Mounier R, Guguin A, Manier C, Surenaud M, Hittinger L, Dubois-Rande JL, Rodriguez AM. Nanotubular crosstalk with distressed cardiomyocytes stimulates the paracrine repair function of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:216–230. doi: 10.1002/stem.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng X, Wang Z, Yang J, Ma M, Lu T, Xu G, Liu X. Acidic fibroblast growth factor delivered intranasally induces neurogenesis and angiogenesis in rats after ischemic stroke. Neurol Res. 2011;33:675–680. doi: 10.1179/1743132810Y.0000000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnefond A, Saulnier PJ, Stathopoulou MG, Grarup N, Ndiaye NC, Roussel R, Nezhad MA, Dechaume A, Lantieri O, Hercberg S, Lauritzen T, Balkau B, El-Sayed Moustafa JS, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Froguel P, Charpentier G, Marre M, Hadjadj S, Visvikis-Siest S. What is the contribution of two genetic variants regulating VEGF levels to type 2 diabetes risk and to microvascular complications? PLoS One. 2013;8:e55921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enomoto S, Yoshiyama M, Omura T, Matsumoto R, Kusuyama T, Nishiya D, Izumi Y, Akioka K, Iwao H, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J. Microbubble destruction with ultrasound augments neovascularisation by bone marrow cell transplantation in rat hind limb ischaemia. Heart. 2006;92:515–520. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayer CR, Bekeredjian R. Ultrasonic gene and drug delivery to the cardiovascular system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1177–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen L, Gao Y, Qian J, Sun A, Ge J. A novel mechanism for endothelial progenitor cells homing: The SDF-1/CXCR4-Rac pathway may regulate endothelial progenitor cells homing through cellular polarization. Med Hypotheses. 2011;76:256–258. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho KA, Ju SY, Ryu KH, Woo SY. Hypoxia affected SDF-1alpha-CXCR4 interaction between bone marrow stem cells and osteoblasts via osteoclast modulation. Acta Haematol. 2010;123:43–47. doi: 10.1159/000262750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai WB, Aiba I, Long Y, Lin HK, Feun L, Savaraj N, Kuo MT. Activation of Ras/PI3K/ERK pathway induces c-Myc stabilization to upregulate argininosuccinate synthetase, leading to arginine deiminase resistance in melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2622–2633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adya R, Tan BK, Punn A, Chen J, Randeva HS. Visfatin induces human endothelial VEGF and MMP-2/9 production via MAPK and PI3K/Akt signalling pathways: novel insights into visfatin-induced angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:356–365. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofseth LJ, Hussain SP, Wogan GN, Harris CC. Nitric oxide in cancer and chemoprevention. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:955–968. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Findley CM, Cudmore MJ, Ahmed A, Kontos CD. VEGF induces Tie2 shedding via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt dependent pathway to modulate Tie2 signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2619–2626. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]