Abstract

We present a rare cause of iridocyclitis in a patient with vitiligo and type 1 diabetes who showed poor metabolic control, and suffered from remitting fever, weight loss, fatigue, diffuse arthralgias and reduced visual acuity. Mild systemic symptoms coupled with increased cholestasis enzymes, insulin resistance, mild inflammation and a functioning adrenal gland focused our clinical work‐up on granulomatous causes of iridocyclitis. Specific tests confirmed syphilis, with no involvement of the central nervous system. Ocular syphilis, despite being unusual, can be the only manifestation of the disease. The work‐up of any unexplained ocular inflammation should include testing for syphilis so as to not delay the diagnosis.

Keywords: Iridocyclitis, Syphilis, Type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Ocular involvement is common in autoimmune disorders; conversely, patients with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (APS) frequently show vitiligo, alopecia, pernicious anemia, chronic hepatitis and uveitis1, 2. Transgenic mice deficient for the autoimmune regulator gene develop type 1 APS and uveitis3. Therefore, searching for other autoimmunity diseases is mandatory in the clinical suspect of APS.

The combination of type 1 diabetes, vitiligo, thyroid disorders and adrenal insufficiency suggests the presence of type 2 APS4; other combinations of organ‐specific autoimmune disease are compatible with type 3 or type 4 APS; however, the autoimmune disease might occur progressively within a wide age span, making the diagnosis difficult. With all this in mind, we suspected an autoimmune origin of iridocyclitis that developed in a patient with vitiligo, type 1 diabetes, alopecia and thyroid disease.

Case Report

A 61‐year‐old man with type 1 diabetes and long‐lasting poor metabolic control (glycated hemoglobin 100 mmol/mol, 11.3%) despite a 96‐IU basal–bolus insulin regimen was referred to our clinic at the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy. His clinical history showed vitiligo, a previous hyperthyroidism corrected with methimazole, a cholecystectomy for gall bladder stones and a prior diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

At the age of 43 years, after a sudden retinal detachment in the left eye, diabetes was diagnosed; insulin therapy was started without further characterization of the disease.

Four months before coming to our attention, the patient suffered for 2 months from a remittent fever (38.5°C), not associated with shivering, and weight loss (−10%); routine blood tests were normal except for mild abnormalities in aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, γ‐glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase. Then he developed a progressive reduction of visual acuity in the right eye; an iridocyclitis was diagnosed, whose etiology was not investigated. He also reported unstable glycemic control, requiring a significant increase in total daily insulin dose, associated with weight loss, fatigue, diffuse arthralgias persisting throughout the day and declining during the night, and sporadic recurrence of mild fever (37–37.5°C).

Clinical examination

The patient was hemodynamically stable. His skin showed signs of segmental vitiligo. His head showed sparse alopecia. An eye examination found bilateral mild miosis with a turbid right iris, and depigmented redness around the cornea and conjunctiva. His thyroid was palpable, with small nodules. Cardiac action was eurhythmic, with no murmurs. A chest examination found kyphosis with sounds of bronchoconstriction. His abdomen was not painful; there was no appreciable liver and spleen enlargement. His genitourinary system showed nothing remarkable. There was no peripheral edema. A neurological examination was normal, apart from a reduction of visual acuity in the right eye.

Biochemical parameters

Complete blood count, C‐reactive protein, international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, uric acid, total protein, bilirubin, lipid profile, creatine kinase, pancreatic amylase and lipase showed normal values. The patient was negative for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and HIV. Anti‐mitochondrial antibodies, anti‐smooth muscle antibodies, anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, anti‐liver kidney microsomal antibodies, scleroderma‐70 kD extractable immunoreactive fragment antibodies, rheumatoid arthritis test, anti‐tissue transglutaminase antibodies, endomysial antibodies, deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies and hormones (thyroid‐stimulating hormone, free tri‐iodothyronine, free thyroxine, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, cortisol, luteinizing hormone, follicle‐stimulating hormone, free testosterone, growth hormone, prolactin, parathyroid hormone) were all normal, as well as thyroid autoantibodies (anti‐thyroglobulin autoantibodies and anti‐thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies: <1 IU/mL for both). A slight positivity of anti‐surrenal gland antibodies was evident. Gamma‐glutamyl transferase (115 U/L; normal value <60), alkaline phosphatase (194 U/L; <115) and erythrocytes sedimentation rate (38 mm/h) showed altered values.

The presence of glutamic acid decarboxylase and tyrosine phosphatase‐like protein IA2 antibodies with undetectable C‐peptide confirmed type 1 diabetes. Despite insulin uptitration, glucose values were extremely variable, with mild hypoglycemic episodes and frequent, severe hyperglycemia. Common causes of poor glycemic control, including neoplasms, were excluded. The combination of vitiligo, alopecia, type 1 diabetes, previous hyperthyroidism and the presence of positive adrenal antibodies allowed the suspicion of type 2 APS, but adrenal function was normal. Therefore, low‐grade fever, fatigue and weight loss, increased cholestasis enzymes, insulin resistance, and mild inflammation focused our clinical work‐up on the granulomatous causes of iridocyclitis: the sexual habits of the patient were investigated; treponemal screening was 40.95 S/CO (normal value <1.0) and a treponemal test found: Treponema pallidum hemoagglutination assay >1:40960, immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M positivity for Treponema pallidum, and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption positive 3+/4+.

Although international guidelines for treatment suggest penicillin‐G as the first‐choice drug for the treatment of all stages of syphilis5, we started with ceftriaxone and doxycycline, continuing at home with benzathine penicillin (four intramuscular doses of 2.4 MU each at 1‐week interval). Immediately after the first dose of ceftriaxone and doxycycline, the patient developed a Jarish–Herxheimer reaction (as a result of a massive release of treponemal antigens); however, in the light of such a reaction and in order to prevent a possible worsening of the ocular manifestations, i.v. methylprednisolone had been administered before starting antimicrobial therapy.

To investigate central nervous system involvement, brain magnetic resonance imaging was carried out (signs of a previous optic neuritis). Lumbar puncture was postponed, as the patient was HIV‐negative and iridocyclitis was the only neurological manifestation of the disease.

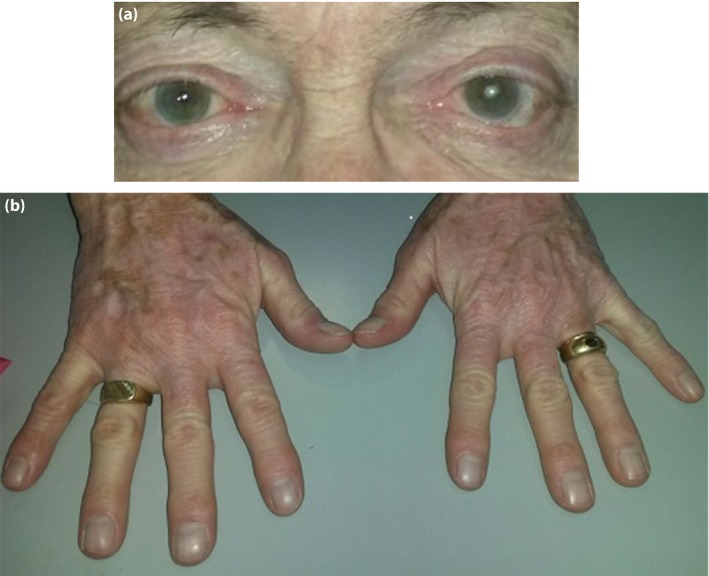

During the follow up, the patient reported subjective well‐being with rapid improvement of visual acuity and eye inflammation (Figure 1). Glycemic control, though still suboptimal, was obtained with a total of 58 IU of insulin. Six months after the diagnosis, Treponema pallidum hemoagglutination assay was 1:10240 and venereal disease research laboratory 1:16.

Figure 1.

The (a) eyes status and (b) vitiligo (detail of the hands) 4 months after the diagnosis.

Discussion

Despite the presence of a clinical phenotype suggestive of APS, the nature of this iridocyclitis was not related to the autoimmune disorder. Acute anterior uveitis can be idiopathic, sometimes HLA‐B27‐linked or granulomatous, the latter either associated with systemic infectious processes, such syphilis, Lyme disease, tuberculosis or herpetic viral infections, or sarcoidosis. In this perspective, specific serology tests should be arranged in case of intractable uveitis of uncertain origin, especially in HIV patients, where macular palcoid chorioretinitis can occur6.

In Italy, 720 cases of syphilis were recorded in the National Health Registry in 2007; 78% occurred in male subjects. According to 2011 World Health Organization data, the estimated number of new cases of curable sexually transmitted diseases in adults, in Europe, is 20 million, of which, in 2010, 17,884 were cases of syphilis7. In the post‐war period, a relationship between syphilis and diabetes was described; recently, an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes has been reported among patients with neurosyphilis; these patients were also characterized by a worse metabolic pattern, with higher fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels8.

Ocular manifestation of syphilis can occur at any stage of the disease, mimic a wide range of ocular disorders, and lead to misdiagnoses and delay in the administration of appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Syphilis is a rare cause of uveitis; it might occur 6 weeks after primary infection, sometimes being the only systemic sign of secondary syphilis, often characterized by optic neuropathy.

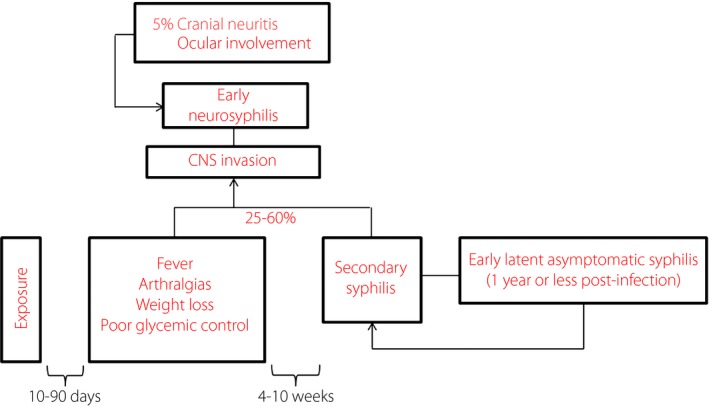

The diagnosis of syphilis in the present patient was, in fact, delayed; a meditated interpretation of the clinical history and a critically‐oriented analysis of laboratory tests would have allowed us to rapidly formulate a correct diagnosis. In fact, as early as 4 months before coming to our attention, the patient started to report symptoms not clearly related to a rise in the hepatobiliary indices in a long term‐cholecystectomized individual. Therefore, a screening for hepatotropic viruses, syphilis and HIV should had been carried out even at that time, because of the presence of risk behaviors. When iridocyclitis developed, it was considered an autoimmune epiphenomenon of a coexisting APS, with this view being supported by the low‐grade inflammation and the worsening glycemic control. Such a hypothesis allowed us to also explain flu‐like symptoms and fever; on the same basis, the suspicion of syphilitic etiology could have been made previously. We attributed the modest rise in liver enzymes to hepatosteatosis, likely worsened by the metabolic and inflammatory derangement. However, it is good practice, when there is an increase in transaminases or cholestasis indexes in the absence of hepatitis or hepatobiliary disease, to carry out screening tests for syphilis, given that various degrees of hepatobiliary involvement are reported in early and late stages of syphilis9, 10. An attempt to correctly define the patient's phenotype, even in the presence of an atypical presentation of the disease (Figure 2), is of particular relevance in a perspective of prevention and early treatment aiming at reducing severe complications and improving the prognosis.

Figure 2.

The natural history of syphilis in the patient. CNS, central nervous system.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study did not receive any financial support.

J Diabetes Investig 2016; 7: 641–644

References

- 1. Mohsenin A, Huang JJ. Ocular manifestations of systemic inflammatory diseases. Conn Med 2012; 76: 533–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davies JB, Rao PK. Ocular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2008; 19: 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeVoss JJ, Shum AK, Johannes KPA, et al Effector mechanisms of the autoimmune syndrome in the murine model of Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Type 1. J Immunol 2008; 181: 4072–4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2068–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N, et al 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28: 1581–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okada AA, Jabs DA. The standardization of uveitis nomenclature project: the future is here. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013; 131: 787–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization . Prevalence and incidence of selected sexually transmitted infections, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, syphilis and Trichomonas vaginalis. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2011. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241502450_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang T, Tong M, Xi Y, et al Association between neurosyphilis and diabetes mellitus: resurgence of an old problem. J Diabetes 2014; 6: 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee RV, Thornton GF, Conn HO. Liver disease associated with secondary syphilis. N Engl J Med 1971; 284: 1423–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ishikawa M, Shimizu I, Uehara K, et al A patient with early syphilis complicated by fatty liver who showed an alleviation of hepatopathy accompanied by jaundice after receiving anti‐syphilitic therapy. Intern Med 2006; 45: 953–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]