Abstract

Background:

This study aims to investigate the association between statin use and all-cancer survival in a prospective cohort of postmenopausal women, using data from the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS) and Clinical Trial (WHI-CT).

Methods:

The WHI study enrolled women aged 50–79 years from 1993 to 1998 at 40 US clinical centres. Among 146 326 participants with median 14.6 follow-up years, 23 067 incident cancers and 3152 cancer deaths were observed. Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate the relationship between statin use and cancer survival.

Results:

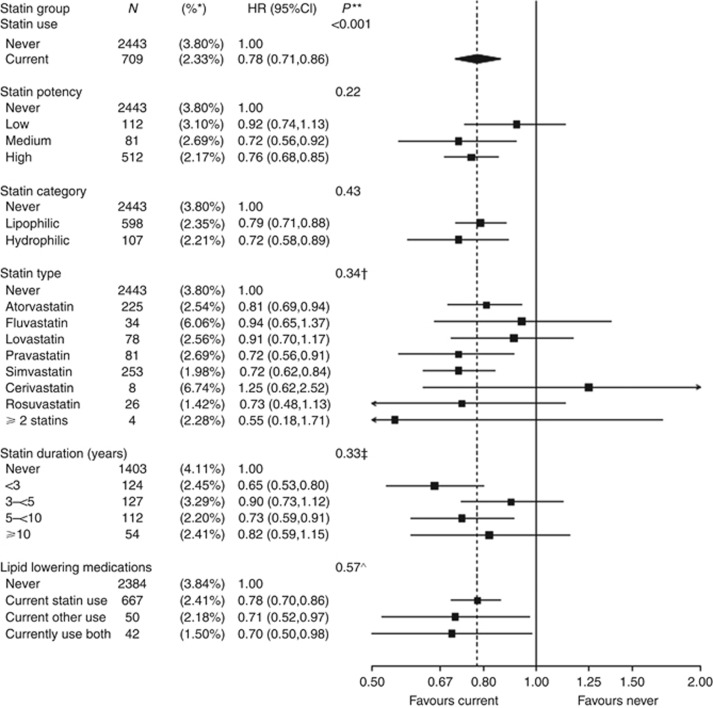

Compared with never-users, current statin use was associated with significantly lower risk of cancer death (hazard ratio (HR), 0.78; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.71–0.86, P<0.001) and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74–0.88). Use of other lipid-lowering medications was also associated with increased cancer survival (P-interaction (int)=0.57). The lower risk of cancer death was not dependent on statin potency (P-int=0.22), lipophilicity/hydrophilicity (P-int=0.43), type (P-int=0.34) or duration (P-int=0.33). However, past statin users were not at lower risk of cancer death compared with never-users (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.85–1.33); in addition, statin use was not associated with a reduction of overall cancer incidence despite its effect on survival (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92–1.001).

Conclusions:

In a cohort of postmenopausal women, regular use of statins or other lipid-lowering medications was associated with decreased cancer death, regardless of the type, duration, or potency of statin medications used.

Keywords: cancer, survival, statins, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor, HMG Co-A reductase inhibitor, cholesterol

Cancer is the second leading cause of death among women in the United States, with over 270 000 cancer deaths in 2015 (Siegel et al, 2015). The use of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor medications (‘statins' or ‘HMG Co-A reductase inhibitors') for cholesterol reduction has been hypothesised to interfere with cancer growth and metastasis through multiple mechanisms (Fenton et al, 1992; Herold et al, 1995; Deberardinis et al, 2008; Gauthaman et al, 2009; Mannello and Tonti, 2009). Current literature on statin use and cancer survival has been mixed (Dale et al, 2006; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators et al, 2012; Murtola et al, 2014; Cardwell et al, 2015; Desai et al, 2015; Wu et al, 2015; Zhong et al, 2015), although a retrospective nationwide Danish study found a statistically significant 15% reduction in all-cancer mortality among patients who used statins before cancer diagnosis (Nielsen et al, 2012).

Given the widespread and rapidly growing statin use in the United States (Stone et al, 2014), we aimed to investigate the relationship between statin use and all-cancer survival in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI). To our best knowledge, this is the first prospective study to investigate statins and all-cancer survival.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and participants

The WHI is a large, multi-centre study designed to study major causes of morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women. The WHI includes a clinical trial (CT) and an observational study (OS) cohort, with details described previously (Hays et al, 2003). Women meeting eligibility criteria (age 50–79, postmenopausal, minimum life expectancy 3 years) were recruited at 40 US clinical centres between 1 September 1993 and 31 December 1998. Primary analyses focused on current statin users among the N=23 067 women who experienced an incident cancer during follow-up (Supplementary Figure 1).

Exposures, confounders, and classification of cases

WHI implementation details have been previously published (Anderson et al, 2003). The medication inventory was repeated at years 1, 3, 6, and 9 for the CT, and year 3 for the OS during the initial study period, which ended on 31 March 2005. The overall follow-up period for the study was through 20 September 2013. Cancers were initially verified at the local clinical centre, and then confirmed by centrally trained physician adjudicators (Curb et al, 2003).

Statistical analysis

Multivariable-adjusted Cox regression techniques were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by modelling two-ordered events: time from enrolment to incident cancer (secondary end point) and time from incident cancer to cancer death (primary end point). Statin use was modelled as a time-dependent categorical variable (Therneau and Grambsch, 2000), with the following levels: (0) never use, (1) current use (at the time of the latest medication inventory), (2) past use, and (3) out-of-date medication inventory (Gong et al, 2016). The primary analysis compared current (1) vs never used statins (0), to investigate the effect of regular statin use.

The Cox proportional hazard analyses were adjusted for potential confounders and included baseline covariates age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, body mass index, physical activity, family history of cancer, current health-care provider, oral contraception use, prior unopposed oestrogen use, prior oestrogen plus progestin use, solar irradiance (latitude), prior CHD history, prior diabetes history, randomisation into the CaD trial, and age at menarche. Participants who did not die of cancer were censored at death due to other causes, last contact, or out-of-date medication collection.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R software version 2.15 (R Foundation for Statistical, Vienna, Austria).

Results

In our analysis, 146 326 participants contributed 1 805 759 person-years, median (interquartile range, IQR)=14.6 (8.1–16.2) years of follow-up. A cumulative 24 404 women were diagnosed with an incident cancer (Supplementary Figure 1). Of this group, 23 067 women had additional follow-up, median (IQR) of 4.8 (1.8–9.4) years, with 7411 all-cause mortalities: 5837 cancer deaths following a diagnosis of incident cancer (78.8%), 613 cardiovascular deaths (8.3%), and 961 other causes (12.9%). After censoring the follow-up of women with out-of-date medication inventories, 3152 cancer deaths were included in the primary analysis of current vs never statin users (709 current statin users and 2443 non-users). Table 1, and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 display baseline characteristics.

Table 1. Participants' characteristics in the Women's Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational Study by statin use (current vs never)a at time of cancer diagnosis (N=17 285b).

|

Current statin use (N=4025) |

Never used statins (N=13 260) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | P-valuec | |

| Age at screening (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| 50–59 | 1123 | 27.9 | 3973 | 30.0 | |

| 60–69 | 2089 | 51.9 | 6228 | 47.0 | |

| 70–79 | 813 | 20.2 | 3059 | 23.1 | |

| Age at incident cancer | <0.001 | ||||

| <70 | 1338 | 33.2 | 6706 | 50.6 | |

| 70 to <80 | 2030 | 50.4 | 5295 | 39.9 | |

| ⩾80 | 657 | 16.3 | 1259 | 9.5 | |

| Tumour stage | 0.001 | ||||

| In situ | 613 | 15.9 | 1732 | 13.8 | |

| Local | 1924 | 49.8 | 6203 | 49.4 | |

| Regional | 702 | 18.2 | 2552 | 20.3 | |

| Distant | 623 | 16.1 | 2079 | 16.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.15 | ||||

| White | 3517 | 87.4 | 11 701 | 88.2 | |

| Black | 261 | 6.5 | 832 | 6.3 | |

| Hispanic | 86 | 2.1 | 310 | 2.3 | |

| American Indian | 16 | 0.4 | 38 | 0.3 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 92 | 2.3 | 234 | 1.8 | |

| Unknown | 53 | 1.3 | 145 | 1.1 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||

| High school/GED or less | 899 | 22.5 | 2617 | 19.9 | |

| School after high school | 1534 | 38.3 | 4812 | 36.5 | |

| College degree or higher | 1570 | 39.2 | 5746 | 43.6 | |

| BMI, baseline (kg m−2) | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 | 1065 | 26.7 | 4745 | 36.1 | |

| 25 to <30 | 1474 | 37.0 | 4468 | 33.9 | |

| 30 to <35 | 882 | 22.1 | 2427 | 18.4 | |

| ⩾35 | 568 | 14.2 | 1522 | 11.6 | |

| Smoking status | 0.75 | ||||

| Never | 1829 | 46.0 | 6115 | 46.7 | |

| Past | 1817 | 45.7 | 5904 | 45.1 | |

| Current | 326 | 8.2 | 1074 | 8.2 | |

| Vitamin D intake (IU) | 0.97 | ||||

| <200 | 1418 | 36.2 | 4690 | 36.1 | |

| 200 to <400 | 737 | 18.8 | 2483 | 19.1 | |

| 400 to <600 | 981 | 25.0 | 3229 | 24.9 | |

| ⩾600 | 784 | 20.0 | 2577 | 19.9 | |

| Alcohol intake | <0.001 | ||||

| Non/past drinker | 1121 | 28.1 | 3252 | 24.7 | |

| <1 drink per week | 1376 | 34.5 | 4367 | 33.2 | |

| 1–<7 drinks per week | 986 | 24.7 | 3656 | 27.8 | |

| ⩾7 drinks per week | 511 | 12.8 | 1890 | 14.4 | |

| Physical activity (MET—min) | 0.03 | ||||

| <100 | 824 | 21.7 | 2683 | 21.6 | |

| 100 to <500 | 1127 | 29.7 | 3420 | 27.5 | |

| 500 to <1200 | 1081 | 28.4 | 3620 | 29.1 | |

| ⩾1200 | 768 | 20.2 | 2709 | 21.8 | |

| Has current health-care provider | 3845 | 96.1 | 12 401 | 94.3 | <0.001 |

| Mammogram within last 2 years | 3465 | 88.1 | 10 822 | 84.1 | <0.001 |

| Hysterectomy at randomisation | 1526 | 37.9 | 4702 | 35.5 | 0.005 |

| Unopposed oestrogen use status | 0.64 | ||||

| Never used | 2668 | 66.4 | 8752 | 66.1 | |

| Past user | 509 | 12.7 | 1752 | 13.2 | |

| Current user | 843 | 21.0 | 2746 | 20.7 | |

| Oestrogen+progesterone use status | <0.001 | ||||

| Never used | 2934 | 72.9 | 9166 | 69.2 | |

| Past user | 340 | 8.5 | 1123 | 8.5 | |

| Current user | 748 | 18.6 | 2964 | 22.4 | |

| Age at menarche | 0.31 | ||||

| <12 | 894 | 22.3 | 2900 | 22.0 | |

| 12–13 | 2262 | 56.4 | 7336 | 55.6 | |

| ⩾14 | 856 | 21.3 | 2970 | 22.5 | |

| Oral contraceptive use ever | 1672 | 41.5 | 5451 | 41.1 | 0.63 |

| CHD before cancer diagnosis | 680 | 17.0 | 756 | 5.7 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes before cancer diagnosis | 725 | 18.0 | 865 | 6.5 | <0.001 |

| Family history of cancer | 2639 | 68.4 | 8888 | 69.8 | 0.12 |

| Aspirin use | 1136 | 28.2 | 2573 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| NSAIDs | 1684 | 41.8 | 4478 | 33.8 | <0.001 |

| DM trial | 0.03 | ||||

| Comparison | 1011 | 62.8 | 2985 | 59.6 | |

| Intervention | 600 | 37.2 | 2020 | 40.4 | |

| CEE+MPA trial | 0.007 | ||||

| Comparison | 283 | 52.7 | 819 | 46.1 | |

| Intervention | 254 | 47.3 | 957 | 53.9 | |

| CEE trial | 0.04 | ||||

| Comparison | 179 | 56.5 | 423 | 49.6 | |

| Intervention | 138 | 43.5 | 430 | 50.4 | |

| CaD trial | 0.15 | ||||

| Comparison | 638 | 53.1 | 1856 | 50.7 | |

| Intervention | 563 | 46.9 | 1803 | 49.3 | |

| Clinical trial participant | 2218 | 55.1 | 6830 | 51.5 | <0.001 |

| Mean | (s.d.) | Mean | (s.d.) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 63.6 | (6.5) | 63.7 | (7.0) | 0.37 |

| Fruit and vegetable consumptiond | 4.0 | (4.0) | 4.1 | (2.1) | 0.004 |

| Red meat consumptiond | 0.7 | (0.5) | 0.7 | (0.6) | 0.27 |

| General health (0 worst–100 best) | 73.6 | (17.2) | 75.9 | (16.7) | <0.001 |

Abbrviations: BMI=body mass index; CaD=calcium + Vitamin D; CEE=conjugated equine estrogen; CHD=coronary heart disease; DM=dietary Modification; GED=general education development; MET=metabolic equivalent; MPA=medroxyprogesterone acetate; NSAID=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Statin (current vs never) were the exposure groups of interest for the primary analysis.

At the time of incident cancer, 23 067 participants were at risk for death and included in the primary analyses. Of these, 4025 participants were currently taking statins; 13 260 participants never used statins; 397 participants had reported using statins at baseline or follow-up, but were not currently taking statins; and 5385 participants had medication inventories that were out of date, so their follow-up was censored. Exposure groups were modelled as a time-dependent exposure, so a participants' group status may change during follow-up (e.g., participants with an out-of-date inventory were allowed to re-enter the model when a current medications inventory was collected).

On the basis of χ2-test of association for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables.

Medium servings per day.

Current statin use was associated with lower risk of cancer death compared with never-use (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.71–0.86; P<0.001; Figure 1), and lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.74–0.88). The lower risk of cancer death associated with statin use did not depend on statin potency (P-interaction (int)=0.22), category (P-int=0.43), type (P-int=0.34), or duration (P-int=0.33). Other lipid-lowering medications, used alone, were associated with a similar reduction in cancer deaths compared with monotherapy statin use (P-int=0.57). Prior statin users were not at lower risk of cancer death compared with never-users (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.85–1.33).

Figure 1.

Number of cancer deaths (annualised %) and multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI) for statin use (current vs never).Annualised percentages by exposure group (time dependent) were computed by dividing the total number of cancer deaths, by the corresponding cumulative person-time since cancer diagnosis, for each exposure group. Cox regression models were adjusted for age at baseline, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, family history of cancer, current health-care provider, oral contraception use, prior unopposed oestrogen use, prior oestrogen plus progestin use, solar irradiance (latitude), prior CHD history, prior diabetes history, randomisation into the CaD trial, age at menarche, and stratified by age group, study groups (randomisation arms of the HT trials, DM trial, and OS enrolment) and enrolment in WHI extensions (I/II). *Annualised percentage. **Significance test of the main effect or test of heterogeneity between non-referent exposure groups. †Test of heterogeneity between atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, and pravastatin. ‡Analysis of statin duration included only CT participants; at the time of cancer diagnosis, among current statin users (n=2218), 893 (40.3%) used statins <3 years, 539 (24.3%) 3 to <5 years, 593 (26.7%) 5 to <10 years, and 193 (8.7%) 10+ years. Test of heterogeneity based on a 1 degree-of-freedom test for trend. ^Test of heterogeneity between statin use and other use.

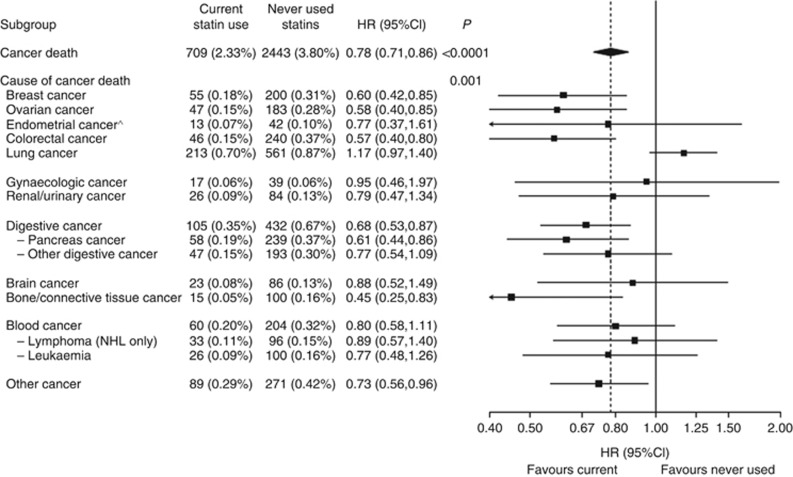

Statin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of multiple, but not all cancer types (P-int=0.001; Figure 2). With the exception of current NSAID use (which attenuated the effect of statins), current statin use was not modified by any other subgroups (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of cancer deaths (annualised %) and multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI) for statin use (current vs never) by cause of cancer death.Summary statistics are from a Cox regression model, using cause-specific baseline hazard functions, with the covariate adjustments described above. *Corresponds to a significance test of the main effect, or an 11-df test of heterogeneity for cause of cancer death. To avoid double counting, test of heterogeneity is between the main causes of death listed and does not include subtypes (i.e., cancer of the pancreas or other digestive organs, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and leukaemia). ^Only participants without a baseline hysterectomy were used to compute the number of cases and annualised rates. There was one endometrial cancer case among the group of no statin use that reported having had a hysterectomy.

In a secondary analysis on cancer incidence, beginning at enrolment, statin use was not associated with a reduction of incident cancer (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92–1.001; P=0.056).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we found that current statin use in postmenopausal women with cancer was associated with lower risk of cancer death. Use of other lipid-lowering medications was also associated with a lower risk of cancer death; this finding suggests that a reduction in circulating cholesterol levels may mediate increased cancer survival. However, a dose–response relationship was not found, suggesting that results should be interpreted cautiously. Multiple molecular mechanisms have been linked to statins and cancer, including the mevalonate pathway (Fenton et al, 1992; Herold et al, 1995; Deberardinis et al, 2008; Boudreau et al, 2010), G-proteins (Wong et al, 2002; Demierre et al, 2005), isoprenoid-mediated suppression (Wong et al, 2002), the RAF-mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 pathway (Wu et al, 2004), and anti-angiogenic properties of statins (Weis et al, 2002).

Comparison with other studies

Our study results are similar to findings from a retrospective nationwide Danish study, which found a statistically significant 15% reduction in all-cancer mortality among patients who used statins before cancer diagnosis (Nielsen et al, 2012). Our analysis is additionally strengthened by its prospective format, ethnically heterogeneous population, and covariate data. In addition, other studies of specific cancers in women (including breast and uterine) have suggested the protective effects of statins on cancer mortality and survival (Murtola et al, 2014; Cardwell et al, 2015; Nevadunsky et al, 2015). Also, some prospective cohort studies of cardiovascular disease have found associations between lower cholesterol levels and lower risk of death from several cancers (Cambien et al, 1980; Kagan et al, 1981; Keys et al, 1985).

However, several smaller studies and RCTs have found no significant associations. A meta-analysis of 27 RCTs in the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators (2015) database did not find an association with cancer mortality or incidence; however, the study used the time from randomisation rather than the time from incident cancer. A meta-analysis of 26 RCTs also found no effect of statin use on cancer incidence or survival (Dale et al, 2006). These conflicting results suggest the need for additional prospective studies and larger RCTs, particularly with cancer survival as the primary outcome.

Cancer incidence has been studied more extensively than cancer survival in relation to statin use, but results on the subject have been mixed (Bjerre and LeLorier, 2001; Bonovas et al, 2005; Browning and Martin, 2007; Kuoppala et al, 2008; Haukka et al, 2010; Jagtap et al, 2012; Simon et al, 2012; Desai et al, 2013; Singh and Singh, 2013; Tan et al, 2013). Similarly, biomarker-based studies of statins as candidate breast cancer chemoprevention agents have shown mixed results (Higgins et al, 2012; Bjarnadottir et al, 2013; Vinayak et al, 2013).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its prospective nature, large size and geographic distribution, adjudication of cancer cases, and detailed information on confounders and exposures. Limitations of the study include the fact that medication use was not continuously updated, observational format, and majority Caucasian participants. The study may not be generalisable to populations other than postmenopausal women with similar age at cancer diagnosis. Residual confounding or reverse causation bias may be present.

Healthy user bias due to socioeconomic factors may also present in this analysis; however, this should be reduced as WHI data allow for rich covariate adjustment. In addition, the effect of statin use on cancer survival remained significant even with sensitivity analyses including tumour stage, physical functioning, and mammogram use.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in a prospective cohort of postmenopausal women, current use of statins and other cholesterol-lowering medications was associated with increased all-cancer survival, as well as increased survival of multiple cancer types. These findings, along with the previous Danish cohort study, suggest that statin use and/or lower cholesterol levels may have a protective effect on cancer death. Further research is needed in an RCT format to better control for healthy user bias and to study cancer as a primary outcome.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the dedicated efforts of investigators and staff at the WHI clinical centres, the WHI Clinical Coordinating Center, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood program office (available at http://www.whi.org). We also recognise the WHI participants for their extraordinary commitment to the WHI program. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C. The WHI is registered under ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000611. This study was approved by the ethics committees at the WHI Coordinating Center, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and all 40 clinical centres.

Author contributors

AW, JT, HW, AK, and MS participated in study conception and design. AA performed the data analysis. AW, AA, JT, HW, AK, and MS participated in initial data interpretation. AW and AA wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to additional data interpretation and revisions and approval of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, Lund B, Hall D, Davis S, Shumaker S, Wang CY, Stein E, Prentice RL (2003) Implementation of the Women's Health Initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol 13(9 Suppl): S5–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadottir O, Romero Q, Bendahl PO, Jirstrom K, Ryden L, Loman N, Uhlen M, Johannesson H, Rose C, Grabau D, Borgquist S (2013) Targeting HMG-CoA reductase with statins in a window-of-opportunity breast cancer trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138(2): 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerre LM, LeLorier J (2001) Do statins cause cancer? A meta-analysis of large randomized clinical trials. Am J Med 110(9): 716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Tsavaris N, Sitaras NM (2005) Use of statins and breast cancer: A meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials and nine observational studies. J Clin Oncol 23(34): 8606–8612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau DM, Yu O, Johnson J (2010) Statin use and cancer risk: a comprehensive review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 9(4): 603–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning DR, Martin RM (2007) Statins and risk of cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Int J Cancer 120(4): 833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambien F, Ducimetiere P, Richard J (1980) Total serum cholesterol and cancer mortality in a middle-aged male population. Am J Epidemiol 112(3): 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell CR, Hicks BM, Hughes C, Murray LJ (2015) Statin use after diagnosis of breast cancer and survival: a population-based cohort study. Epidemiology 26(1): 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators (2015) Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174 000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet 385(9976): 1397–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators, Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Keech A, Simes J, Barnes EH, Voysey M, Gray A, Collins R, Baigent C (2012) The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 380(9841): 581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, Kooperberg C, Stanford J, Nevitt M, Johnson KC, Proulx-Burns L, Pastore L, Criqui M, Daugherty S WHI Morbidity and Mortality Committee (2003) Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women's Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol 13(9 Suppl): S122–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, Kluger J, White CM (2006) Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. JAMA 295(1): 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB (2008) Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18(1): 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demierre MF, Higgins PD, Gruber SB, Hawk E, Lippman SM (2005) Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer 5(12): 930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai P, Chlebowski R, Cauley JA, Manson JAE, Wu CY, Martin LW, Jay A, Bock C, Cote M, Petrucelli N, Rosenberg CA, Peters U, Agalliu I, Budrys N, Abdul-Hussein M, Lane D, Luo JH, Park HL, Thomas F, Wactawski-Wende J, Simon MS (2013) Prospective analysis of association between statin use and breast cancer risk in the Women's Health Initiative. Cancer Epidem Biomar 22(10): 1868–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai P, Lehman A, Chlebowski RT, Kwan ML, Arun M, Manson JE, Lavasani S, Wasswertheil-Smoller S, Sarto GE, LeBoff M, Cauley J, Cote M, Beebe-Dimmer J, Jay A, Simon MS (2015) Statins and breast cancer stage and mortality in the Women's Health Initiative. Cancer Causes Control 26(4): 529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton RG, Kung HF, Longo DL, Smith MR (1992) Regulation of intracellular actin polymerization by prenylated cellular proteins. J Cell Biol 117(2): 347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthaman K, Fong CY, Bongso A (2009) Statins, stem cells, and cancer. J Cell Biochem 106(6): 975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Aragaki AK, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, Rohan TE, Chen C, Vitolins MZ, Tinker LF, LeBlanc ES, Kuller LH, Hou L, LaMonte MJ, Luo J, Wactawski-Wende J (2016) Diabetes, metformin and incidence of and death from invasive cancer in postmenopausal women: Results from the women's health initiative. Int J Cancer 138(8): 1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukka J, Sankila R, Klaukka T, Lonnqvist J, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, Wahlbeck K, Tiihonen J (2010) Incidence of cancer and statin usage—record linkage study. Int J Cancer 126(1): 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Limacher M, Allen C, Rossouw JE (2003) The Women's Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol 13(9 Suppl): S18–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold G, Jungwirth R, Rogler G, Geerling I, Stange EF (1995) Influence of cholesterol supply on cell growth and differentiation in cultured enterocytes (CaCo-2). Digestion 56(1): 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins MJ, Prowell TM, Blackford AL, Byrne C, Khouri NF, Slater SA, Jeter SC, Armstrong DK, Davidson NE, Emens LA, Fetting JH, Powers PP, Wolff AC, Green H, Thibert JN, Rae JM, Folkerd E, Dowsett M, Blumenthal RS, Garber JE, Stearns V (2012) A short-term biomarker modulation study of simvastatin in women at increased risk of a new breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131(3): 915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap D, Rosenberg CA, Martin LW, Pettinger M, Khandekar J, Lane D, Ockene I, Simon MS (2012) Prospective analysis of association between use of statins and melanoma risk in the Women's Health Initiative. Cancer 118(20): 5124–5131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan A, McGee DL, Yano K, Rhoads GG, Nomura A (1981) Serum cholesterol and mortality in a Japanese-American population: the Honolulu Heart program. Am J Epidemiol 114(1): 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A, Aravanis C, Blackburn H, Buzina R, Dontas AS, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Menotti A, Nedeljkovic S, Punsar S, Toshima H (1985) Serum cholesterol and cancer mortality in the Seven Countries Study. Am J Epidemiol 121(6): 870–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A, Pukkala E (2008) Statins and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 44(15): 2122–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannello F, Tonti GA (2009) Statins and breast cancer: may matrix metalloproteinase be the missing link. Cancer Invest 27(4): 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtola TJ, Visvanathan K, Artama M, Vainio H, Pukkala E (2014) Statin use and breast cancer survival: a nationwide cohort study from Finland. PloS One 9(10): e110231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevadunsky NS, Van Arsdale A, Strickler HD, Spoozak LA, Moadel A, Kaur G, Girda E, Goldberg GL, Einstein MH (2015) Association between statin use and endometrial cancer survival. Obstet Gynecol 126(1): 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE (2012) Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N Engl J Med 367(19): 1792–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2015) Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 65(1): 5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MS, Rosenberg CA, Rodabough RJ, Greenland P, Ockene I, Roy HK, Lane DS, Cauley JA, Khandekar J (2012) Prospective analysis of association between use of statins or other lipid-lowering agents and colorectal cancer risk. Ann Epidemiol 22(1): 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PP, Singh S (2013) Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 24(7): 1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, McBride P, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC Jr. Watson K, Wilson PW American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (2014) 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 63(25 Pt B): 2889–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Song X, Zhang G, Peng A, Li X, Li M, Liu Y, Wang C (2013) Statins and the risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Plos One 8(2): e57349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM, Grambsch PM (2000) Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Vinayak S, Schwartz EJ, Jensen K, Lipson J, Alli E, McPherson L, Fernandez AM, Sharma VB, Staton A, Mills MA, Schackmann EA, Telli ML, Kardashian A, Ford JM, Kurian AW (2013) A clinical trial of lovastatin for modification of biomarkers associated with breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 142(2): 389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis M, Heeschen C, Glassford AJ, Cooke JP (2002) Statins have biphasic effects on angiogenesis. Circulation 105(6): 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WW, Dimitroulakos J, Minden MD, Penn LZ (2002) HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the malignant cell: the statin family of drugs as triggers of tumor-specific apoptosis. Leukemia 16(4): 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Wong WW, Khosravi F, Minden MD, Penn LZ (2004) Blocking the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway sensitizes acute myelogenous leukemia cells to lovastatin-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res 64(18): 6461–6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu QJ, Tu C, Li YY, Zhu J, Qian KQ, Li WJ, Wu L (2015) Statin use and breast cancer survival and risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 6(40): 42988–43004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Zhang X, Chen L, Ma T, Tang J, Zhao J (2015) Statin use and mortality in cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Treat Rev 41(6): 554–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.