Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is one of the most prevalent liver diseases and increases the risk of fibrosis and cirrhosis. Current standard treatment focuses on lifestyle interventions. The primary aim of this study was to assess the effects of a short-term low-calorie diet on hepatic steatosis, using the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) as quantitative tool.

METHODS:

In this prospective observational study, 60 patients with hepatic steatosis were monitored during a hypocaloric high-fiber, high-protein diet containing 1,000 kcal/day. At baseline and after 14 days, we measured hepatic fat contents using CAP during transient elastography, body composition with bioelectrical impedance analysis, and serum liver function tests and lipid profiles using standard clinical–chemical assays.

RESULTS:

The median age was 56 years (25–78 years); 51.7% were women and median body mass index was 31.9 kg/m2 (22.4–44.8 kg/m2). After 14 days, a significant CAP reduction (14.0% P<0.001) was observed from 295 dB/m (216–400 dB/m) to 266 dB/m (100–353 dB/m). In parallel, body weight decreased by 4.6% (P<0.001), of which 61.9% was body fat. In addition, liver stiffness (P=0.002), γ-GT activities, and serum lipid concentrations decreased (all P<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

This study shows for the first time that non-invasive elastography can be used to monitor rapid effects of dietary treatment for hepatic steatosis. CAP improvements occur after only 14 days on short-term low-calorie diet, together with reductions of body composition parameters, serum lipids, and liver enzymes, pointing to the dynamics of hepatic lipid turnover.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a spectrum of progressive liver conditions in the absence of significant alcohol consumption. Bland steatosis occurs when intrahepatic triglycerides accumulate in hepatocytes, which may progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) if accompanied by inflammation.1 In 10–25% of patients, steatosis advances to hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease. In addition, the likelihood of cardiovascular disease is increased when NAFLD occurs, and consequently, these patients have an increased risk of overall and liver-specific mortality.2, 3 NAFLD has emerged as one of the most widespread liver diseases in western societies, with prevalence estimates ranging up to 50% and even higher in diabetics.4 This variation is based on differences in screening and detection strategies as well as genetic and environmental risk factors.5, 6 For instance, overweight, type 2 diabetes7 as well as genetic predisposition, such as the patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 (PNPLA3) variant p.I148M, are all implicated in fatty liver manifestation.8, 9 Specifically, carriers of the PNPLA3 risk allele carry a more than twofold increased steatosis risk10 as well as an increased likelihood of developing fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.11, 12

Currently, treatment options for NAFLD are limited and no accepted standard pharmacotherapy exists. According to AASLD guidelines, reduction of body weight of at least 3–5% through a hypocaloric diet alone or together with increased physical activity has been recommended to reduce steatosis.1 Lifestyle intervention studies, specifically diet alone (such as, low-fat or low-carbohydrate diets) or combined with physical activity, have shown potential in ameliorating hepatic steatosis.13, 14 Specifically, preliminary data suggests that a protein-enriched dietary intervention reduces hepatic steatosis in obese patients.15 However, the majority of studies have employed serum surrogate markers,16 semiquantitative ultrasonography,17 elaborate computer tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.18 Only few studies have used liver biopsy, the “gold standard” for assessing histological changes in hepatic steatosis,19, 20 which carries a risk of bleeding and is affected by sampling errors.21, 22 The use of non-invasive and risk-free techniques to diagnose and monitor hepatic steatosis is highly sought after.23 As such, non-invasive techniques are increasingly being evaluated. During ultrasound-based vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE), the attenuation of low-frequency ultrasound waves by liver tissue can be measured. The controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) quantifies liver fat (while simultaneously detecting liver stiffness).24 VCTE is the most widely validated technique for the detection of liver fibrosis, as documented by the new European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommendations on non-invasive tests for the evaluation of liver diseases.25

Until now, no study has compared CAP at baseline and at follow-up in combination with a dietary intervention. The aim of this study was to monitor patients with hepatic steatosis receiving a short-term hypocaloric high-fiber, high-protein diet with the primary outcome of improving liver fat, as quantified with CAP. We hypothesized that this 14-day low-calorie diet would significantly reduce CAP and therefore hepatic steatosis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

This prospective observational pilot study followed patients with fatty liver taking part in a dietary program at four nutrition centers between September 2013 and April 2014 in the Saarland and Palatinate region in Southwest Germany. Specifically, patients received a 14-day hypocaloric high-fiber, high-protein liquid formula diet (HEPAFAST) containing three shakes per day with a total of 786 kcal (41% protein, 29% carbohydrate, 24% fat, and 6% fiber). The formula alone consists of 14.2 g soluble fiber (soluble to insoluble fiber ratio of 3:2) and provides 21 g of total fiber daily. Table 1 summarizes the full nutrient composition. In addition, one to two portions of non-starchy vegetables were recommended daily, bringing the total energy intake to 1,000 kcal/day. To support digestion of the fiber-enriched product, patients were advised to drink at least 2 l of calorie-free beverages per day. Group meetings were offered at baseline and after seven and 14 days to provide background information and to support compliance with the diet. No other specific dietary or physical activity targets were given. The patients were asked to maintain their habitual level of physical activity.

Table 1. HEPAFAST nutrient composition.

| Per 100 g of powdered product | Per 30 g of powdered product in 350 ml milk (fat content 1.5%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy and nutrient content | ||

| Energy | 324 kcal (1,359 kJ) | 262 kcal (1,100 kJ) |

| Fat | 4.8 g | 7.0 g |

| Saturated fat | 1.5 g | 3.6 g |

| Total carbohydrate | 5.8 g | 19.0 g |

| Sugar | 3.5 g | 18.0 g |

| Fiber | 24.0 g | 7.0 g |

| Protein | 51.0 g | 27.0 g |

| Sodium | 101 mg | 195 mg |

| Key ingredients | ||

| l-carnitine | 2,000 mg | 600 mg |

| Taurine | 2,000 mg | 600 mg |

| Omega-3-fatty acids | 1,140 mg | 342 mg |

| Choline | 550 mg | 165 mg |

| Oatmeal | 20.0 g | 6.0 g |

| β-glucan | 5.6 g | 1.7 g |

| Inulin | 7.3 g | 2.2 g |

| Oat fiber | 5.0 g | 1.5 g |

The primary outcome of this study was the effect of the dietary intervention on liver fat contents as measured by CAP. Secondary outcomes included changes in body composition, liver stiffness measurements (LSM), serum lipid concentrations, and cardiovascular risk profile. At the Department of Medicine II of Saarland University Medical Center (Homburg, Germany), we quantified CAP and LSM, and determined body composition. Patients were included in the study if they had a CAP≥215 dB/m at baseline and were excluded from observation if they had any of the following: harmful alcohol intake based on the AUDIT questionnaire,26 histologically defined liver cirrhosis or LSM≥13 kPa,27 pregnancy, cardiac pacemaker, or stage IV or V chronic kidney disease.28

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study protocol complies with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the Saarland Ethics Committee (Ärztekammer des Saarlandes, ref. 271/11).

Anthropometric, clinical and biochemical assessments

After an 8-h overnight fast, the following parameters were measured: height was recorded using a stadiometer (seca 217; Seca, Hamburg, Germany), weight and body composition (body mass index, BMI; body fat mass, BFM; body fat free mass, BFFM; total body water, TBW; visceral fat index, VFI) were assessed using a segmental bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Tanita BC-418MA; Tanita Europe, Sindelfingen, Germany), and waist circumference (WC) was measured using a tape measure aligned at the lowest border of the rib cage in an exhaled and relaxed position. Office systolic and diastolic blood pressure was taken using a digital blood pressure monitor (Visomat; UEBE Medical, Wertheim, Germany). Medical history and current medication were documented. At baseline, 16 patients stated that they took no medication, and 44 listed their current medication, including antihypertensives (N=28), antidiabetics (N=14) and lipid-lowering agents (N=11). At the end of the intervention, antihypertensives were discontinued in five and metformin in three cases; of note, no new medication was started during the intervention.

Fasted blood samples were collected for routine analysis of liver function tests and serum lipids: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (AP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT), pseudocholinesterase (PChE), triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol as well as uric acid, glucose, HbA1c, and kidney function tests. Fatty liver index (FLI), which is based on BMI, WC, γ-GT, and TG, was calculated according to Bedogni et al.:29

Non-invasive assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis

Hepatic steatosis and liver stiffness were assessed using VCTE (FibroScan, Echosens, Paris). At 3.5 MHz, the M-probe provides CAP values (100–400 dB/m) and LSM values (1.5–75.0 kPa), as described in our previous study.10 All elastrography measurements were carried out in fasted patients by the same experienced operator (AA, who has carried out >600 measurements). According to the 2015 EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines for non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis,25 results were only included if they fulfilled the criteria for a valid transient elastography measurement: at least 10 valid shots, a success rate of ≥60%, and an interquartile range (IQR)/liver stiffness (LSM) of ≤30%.

Genotyping of the PNPLA3 variant p.I148M

DNA was isolated from EDTA blood according to membrane-based QIAamp DNA extraction protocol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genotying of the PNPLA3 single nucleotide polymorphism rs738409 (c.617G>C, resulting in the amino acid substitution p.I148M) was conducted using a PCR-based assay with 5′-nuclease and fluorescence detection (TaqMan, Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany; rs738409: C__7241_10) as decribed.11

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Munich, Germany) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). A two-sided P value<0.05 was regarded as significant. Most of the variables were non-parametric, as assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Results are presented as medians and ranges, unless stated otherwise, or as frequencies and percentages.

Variables were tested for correlation using the Spearman's rank coefficient rs. Contingency tables were used to assess for associations between categorical variables. Parameter changes after the dietary intervention are reported as absolute and relative frequencies. Comparisons between two and three unpaired groups were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively. The Wilcoxon-signed ranks tests were used for comparisons between two paired groups. Both linear univariate and multivariate regression analysis were employed to detect the influence of baseline variables on absolute CAP changes. We also carried out subgroup analyses assessing for sex-specific differences, patients with and without type 2 diabetes, and comparing CAP responders (defined by CAP reduction) with CAP non-responders (defined by CAP increase).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

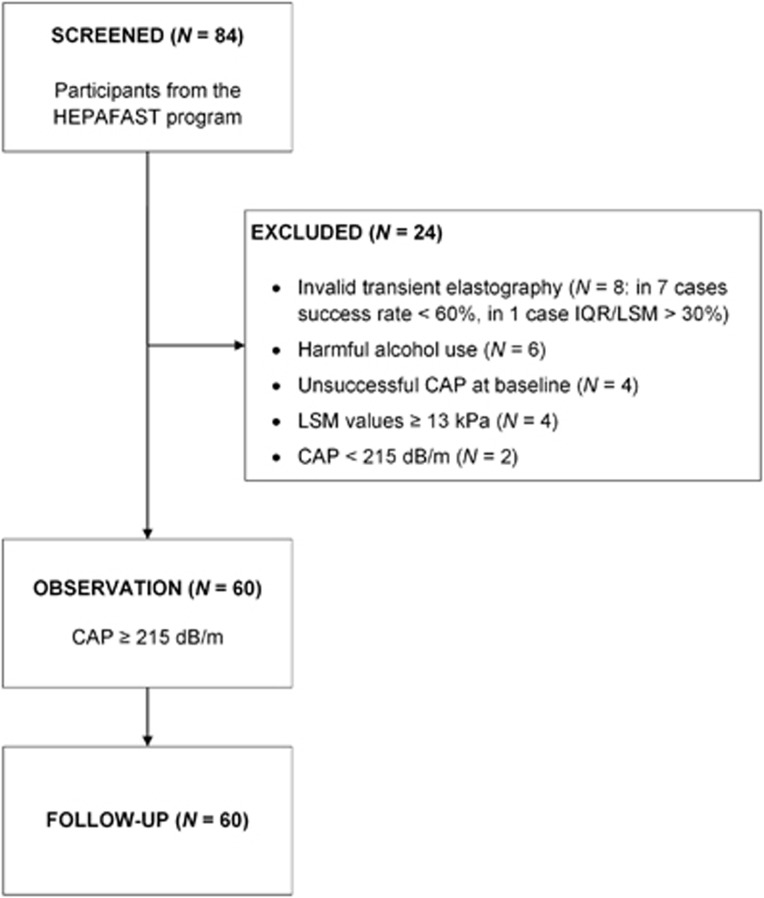

A total of 84 patients were screened for this open study. As depicted in the flow chart (Figure 1), 24 patients were excluded, mainly due to invalid transient elastography (N=8) or harmful alcohol use (N=6), and none of the 60 patients was lost to follow-up. Table 2 summarizes their clinical characteristics. The cohort comprised 31 (51.7%) women and had a median age of 56 years (25–78 years). Median CAP was 295 dB/m (216–400 dB/m). As stated in Methods, the presence of steatosis (steatosis grade ≥S1) was confirmed based on a CAP≥215 dB/m.30 This cut-off has been validated by de Lédinghen et al.30 with an area under receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.84 (95% confidence interval; 0.76–0.92) in reference to liver biopsy. Alternatively, fatty liver can be defined using the FLI, with values ≥60 indicating steatosis.29 At baseline, CAP≥215 dB/m and FLI≥60 were simultaneously detected in 50 (83.3%) patients, and only three cases presented with FLI<30 (rs=0.465, P<0.001). Three patients had normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), 19 (31.7%) were overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and 38 patients (63.3%) were obese (BMI≥30.0 kg/m2). In addition, 55 (91.6%) patients had elevated BFM. In total, 57 patients (95.0%) were above the European WC thresholds of 94 cm for men and 80 cm for women.31 Median HbA1c was 5.7% (4.9–10.4%), and type 2 diabetes was present in 14 (23.3%) patients. Overall, 26 patients (43.3%) presented with the metabolic syndrome, defined as elevated WC, TG, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and reduced HDL cholesterol, as outlined by the International Diabetes Federation.31 Baseline activity level was monitored through a self-report questionnaire, specifically type, frequency and duration of physical activity. At follow-up, an increase in activity level was reported in a single patient only.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study recruitment and participation.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of the study cohort.

| At baseline | At follow-up | Relative reduction (%) | P | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| N (men/women) | 60 (29/31) | |||

| Age (years) | 56 (25–78) | |||

| Body composition | ||||

| Body weight (kg) | 95.1 (60.7–125.6) | 90.5 (58.2–120.1) | −4.6 (−8.0–−0.7) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.9 (22.4–44.8) | 30.6 (21.3–43.5) | −4.7 (−8.1–−0.6) | <0.001 |

| BFM (kg) | 34.5 (16.8–63.4) | 31.8 (13.4–59.5) | −6.9 (−27.0–4.6) | <0.001 |

| BFFM (kg) | 58.2 (39.5–84.9) | 55.3 (39.3–81.9) | −3.3 (−9.1–4.2) | <0.001 |

| TBW (kg) | 42.6 (28.9–62.2) | 40.5 (28.8–60.0) | −3.3 (−9.1–4.1) | <0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 107 (78–127) | 103 (76–128) | −4.1 (−9.2–2.2) | <0.001 |

| VFI | 13 (5–24) | 12 (4–21) | −7.1 (−20.0–11.1) | <0.001 |

| Liver markers | ||||

| CAP (dB/m) | 295 (216–400) | 266 (100–353) | −14.0 (−68.6–38.2) | <0.001 |

| FLI | 83 (7–99) | 63 (4–98) | −21.3 (−74.0–0.0) | <0.001 |

| LSM (kPa) | 6.2 (1.5–11.9) | 5.3 (1.5–12.0) | −11.7 (−70.5–43.6) | 0.002 |

| ALT (U/l) | 38 (12–118) | 36 (14–150) | 0 (−73.1–122.2) | >0.05 |

| AST (U/l) | 25 (10–121) | 24 (8–141) | 0 (−80.2–464.0) | >0.05 |

| AP (U/l) | 74 (37–159) | 64 (32–144) | −11.5 (−43.0–24.1) | <0.001 |

| γ-GT (U/l) | 37 (7–335) | 26 (7–113) | −26.7 (−77.3–50.0) | <0.001 |

| PChE (kU/l) | 10.7 (6.6–17.0) | 10.4 (6.7–15.3) | −3.8 (−22.6–19.2) | 0.006 |

| Metabolic markers | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 89 (63–232) | 84 (60–126) | −7.1 (−50.4–52.4) | <0.001 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 128 (60–419) | 83 (48–183) | −34.1 (−84.0–35.9) | <0.001 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 214 (147–303) | 163 (95–249) | −23.5 (−45.6–10.9) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 142 (78–226) | 96 (45–193) | −25.3 (−53.1–41.0) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 50 (29–110) | 45 (28–77) | −13.0 (−66.4–28.9) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.1 (2.9–8.6) | 5.6 (3.1–10.0) | −7.6 (−40.9–43.5) | 0.024 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 138 (110–175) | 130 (104–184) | −5.6 (−28.6–40.5) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 92 (74–125) | 87 (72–120) | −4.5 (−34.2–18.8) | 0.001 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BFFM, body fat free mass; BFM, body fat mass; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FLI, fatty liver index; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; N, number; PChE, pseudocholinesterase; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TBW, total body water; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VFI, visceral fat index; WC, waist circumference.

Significant P values are highlighted in bold.

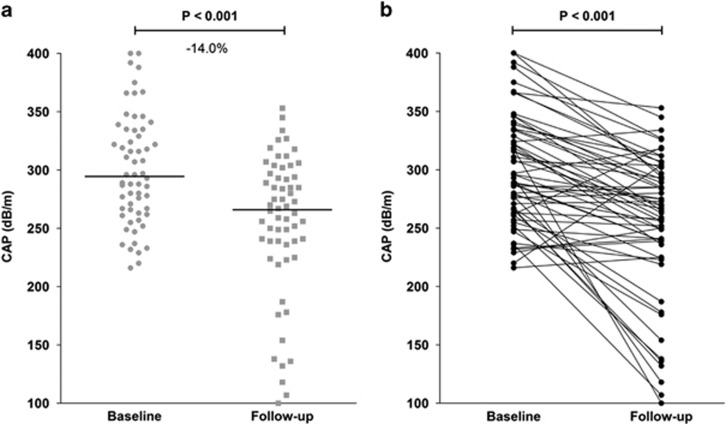

The dietary intervention has a positive impact on CAP

Overall, the median CAP decreased significantly by 14.0% (47 dB/m, P<0.001, Figure 2a) from 295 dB/m (216–400 dB/m) to 266 dB/m (100–353 dB/m) (Table 2). Figure 2b displays all CAP values of individual patients.

Figure 2.

Changes of CAP in all 60 patients. (a) Median and individual CAP at baseline and follow-up at the end of the dietary intervention. The median CAP reduction was 47 dB/m in the entire cohort, corresponding to a relative median reduction of 14.0% (P<0.001). (b) Absolute CAP in the individual patients during the dietary intervention.

Of 60 patients, 49 (81.7%) demonstrated a decrease in median CAP of 15.9% (50 dB/m, P<0.001) and were defined as CAP responders (see Statistical analysis). Of these, 10 patients (20.4%) showed resolution of steatosis, i.e., they presented with CAP<215 dB/m after the dietary intervention. Interestingly, 11 demonstrated a median CAP increase of 3.4% (9 dB/m, P=0.003) after the 14-day intervention despite improvements in body composition, thus we classified them as CAP non-responders. Compared to responders, non-responders were mostly women (72.7 vs. 46.9%, P>0.05), younger (51 vs. 56 years, P>0.05), had a higher baseline BMI (32.2 vs. 31.2 kg/m2, P>0.05) and a lower baseline CAP (262 vs. 308 dB/m, P=0.001). When comparing genetic variation, all five homozygous PNPLA3 mutation carriers with two prosteatogenic p.148M alleles were responders.

The dietary response might be influenced by PNPLA3

In this cohort, the PNPLA3 p.148M frequencies for wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous genotypes were [II]: N=36, 60.0% [IM]: N=19, 31.7% and [MM]: N=5, 8.3%. With a minor allele frequency of 0.24 for the risk allele [M], this result is comparable to 0.23 reported in the first genome-wide association study.8 Homozygous carriers of the prosteatogenic [M] allele had a markedly higher baseline CAP (339 dB/m) as compared to wild-type (291 dB/m) and heterozygous (296 dB/m) patients and as shown in Table 3, they had a slightly larger decrease in CAP at 14 days (P>0.05).

Table 3. Distribution of CAP values across PNPLA3 genotypes.

| PNPLA3 variant p.I148M | [II] | [IM] | [MM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | 60.0 | 31.7 | 8.3 |

| N | 36 | 19 | 5 |

| CAP at baseline (dB/m) | 291 (216–400) | 296 (232–392) | 339 (267–367) |

| CAP at follow-up (dB/m) | 269 (100–353) | 256 (154–334) | 292 (132–306) |

| Absolute median CAP reduction (dB/m) | −48 (−218–84) | −39 (−123–57) | −49 (−135–−22) |

| Relative median CAP reduction (%) | −13.8 (−68.6–38.2) | −14.1 (−44.4–21.8) | −14.4 (−50.6–−7.6) |

CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; I, isoleucine; M, methionine; N, number; PNPLA3, patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 (adiponutrin).

The distribution of CAP values and CAP reduction across PNPLA3 p.I148M genotypes does not differ (all P values>0.05).

Factors associated with CAP

CAP at baseline was associated with BMI (rs=0.330, P=0.010), WC (rs=0.414, P=0.001), LSM (rs=0.460, P<0.001), ALT (rs=0.455, P<0.001), AST (rs=0.412, P=0.001), and glucose concentrations (rs=0.366, P=0.004), but not with TG or γ-GT. Table 4 summarizes the results of univariate regression analysis with absolute reduction of CAP as dependent variable. Age, baseline BFM, BMI, sex, TC, and TG were not correlated, whereas both baseline CAP and HDL cholesterol showed a significant inverse association (P=0.035 and P=0.009, respectively). In multivariate regression analysis, these two variables were independent predictors of absolute CAP reduction (P=0.020 and P=0.005, respectively). As expected, CAP at follow-up correlated with FLI (rs=0.502, P<0.001).

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate analysis of determinants of CAP reduction.

| β coefficient | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Age | 0.042 | >0.05 |

| BFM at baseline | 0.126 | >0.05 |

| BMI at baseline | 0.142 | >0.05 |

| CAP at baseline | −0.273 | 0.035 |

| HDL cholesterol at baseline | −0.335 | 0.009 |

| Sex | 0.178 | >0.05 |

| TC at baseline | −0.062 | >0.05 |

| TG at baseline | 0.206 | >0.05 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| CAP at baseline | −0.285 | 0.020 |

| HDL cholesterol at baseline | −0.345 | 0.005 |

BFM, body fat mass; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Significant P values are highlighted in bold.

Changes of liver stiffness and liver enzymes

Patients presented with a median LSM of 6.2 kPa (1.5–11.9 kPa) at baseline and 5.3 kPa (1.5–12.0 kPa) after the intervention (Table 2). Overall, median LSM decreased by 11.7% (0.8 kPa, P=0.002). With respect to liver function tests, baseline γ-GT activity was elevated in 35% of cases compared to 20% after the intervention. Significant reductions of 26.7 and 11.5% were observed for γ-GT and AP activities, respectively (both P<0.001; Table 2). Although no overall reduction in ALT and AST activities occurred, non-significant (P>0.05) improvements in patients with elevated baseline activities were detected.

Effects on body composition

All 60 patients were compliant with the program when using weight loss as a marker. Overall, the parameters related to body composition decreased significantly, as summarized in Table 2 (all P<0.001). A median weight reduction of 4.6% (4.2 kg, P<0.001) occurred. A total of 17 (28.3%) patients were reclassified into a lower BMI category after 14 days, whereas 43 (71.7%) remained within their initial category. Table 2 shows that BFM decreased by 6.9% (2.6 kg, P<0.001). Overall, 61.9% of the weight reduction was based on loss of BFM. The absolute BFM reduction did not correlate with the reduction of CAP (rs=−0.04, P>0.05).

Reductions in CAP between patients with a weight reduction ≥5 and <5% were similar (14.9 and 11.4%, both P<0.001). Table 5 summarizes within and between group changes.

Table 5. Comparison of patients with weight loss ≥5 and <5%.

|

Weight loss ≥5% |

Weight loss <5% |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline | At follow-up | At baseline | At follow-up | P | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| N (men/women) | 26 (20/6) | 34 (9/25) | *** | ||

| Age (years) | 50 (25–66) | 58 (33–78) | ** | ||

| Body composition | |||||

| Body weight (kg) | 92.8 (61.9–125.6) | 86.7 (58.6–115.7)### | 95.6 (60.7–125.5) | 92.1 (58.2–120.1)### | *** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.6 (22.4–41.5) | 27.8 (21.3–38.5)### | 32.4 (25.3–44.8) | 30.9 (24.2–43.5)### | *** |

| BFM (kg) | 29.2 (17.0–49.5) | 26.0 (13.4–44.1)### | 36.7 (16.8–63.4) | 34.8 (15.4–59.5)### | *** |

| BFFM (kg) | 68.4 (45.8–84.9) | 66.6 (44.4–81.9)### | 53.2 (39.5–77.1) | 51.8 (39.3–78.9)### | *** |

| TBW (kg) | 50.1 (33.5–62.2) | 48.8 (32.5–60.0)### | 38.9 (28.9–56.4) | 37.9 (28.8–57.8)### | *** |

| WC (cm) | 103 (82–124) | 98 (77–120)### | 107 (78–127) | 104 (76–128)### | *** |

| VFI | 12 (5–24) | 12 (5–21)### | 14 (5–21) | 13 (4–20)### | ** |

| Liver markers | |||||

| CAP (dB/m) | 295 (216–400) | 251 (100–345)### | 298 (220–392) | 283 (136–353)### | n.s. |

| FLI | 82 (30–99) | 42 (14–93)### | 83 (7–99) | 71 (4–98)### | *** |

| LSM (kPa) | 5.9 (1.5–11.9) | 5.0 (1.5–12.0)## | 6.2 (3.8–9.7) | 5.4 (3.1–10.0)# | n.s. |

| ALT (U/l) | 38 (12–118) | 31 (14–150)n.s. | 37 (18–108) | 40 (14–105)n.s. | n.s. |

| AST (U/l) | 26 (10–121) | 22 (11–141)n.s. | 24 (10–46) | 24 (8–46)n.s. | n.s. |

| γ-GT (U/l) | 40 (12–335) | 26 (7–99)### | 36 (7–93) | 25 (7–113)### | ** |

| Metabolic markers | |||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 87 (71–232) | 74 (60–115)### | 91 (63–164) | 85 (72–126)## | ** |

| TG (mg/dl) | 138 (60–419) | 72 (48–148)### | 119 (63–340) | 102 (49–183)### | *** |

| TC (mg/dl) | 219 (147–303) | 161 (95–229)### | 209 (149–302) | 166 (103–249)### | * |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 143 (84–201) | 98 (45–172)### | 140 (78–226) | 95 (47–193)### | n.s. |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 46 (33–110) | 42 (28–75)## | 54 (29–82) | 46 (30–77)### | n.s. |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BFFM, body fat free mass; BFM, body fat mass; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; FLI, fatty liver index; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; N, number; TBW, total body water; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VFI, visceral fat index; WC, waist circumference.

P value between baseline and follow-up determined with the Wilcoxon-signed rank test: ###P≤0.001, ##P≤0.01, #P≤0.05, n.s.P>0.05. P value between relative difference of baseline and follow-up value between both groups (weight loss ≥5% and weight loss <5%) determined with the Mann–Whitney U test: ***P≤0.001, **P≤0.01, *P≤0.05, n.s. P>0.05.

Overall, 14 (23.3%) patients had a previous diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. When compared to non-diabetics, these patients were older, had higher serum glucose concentrations and higher baseline CAP, but CAP reductions did not differ between the two groups (Table 6).

Table 6. Clinical baseline characteristics stratified according to the presence of diabetes.

| Patients with diabetes | Patients without diabetes | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| N (men/women) | 14 (6/8) | 46 (23/23) | >0.05 |

| Age (years) | 61 (36–74) | 54 (25–78) | 0.038 |

| Body composition | |||

| Body weight (kg) | 95.3 (74.5–119.8) | 94.5 (60.7–125.5) | >0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.9 (27.0–44.8) | 31.9 (22.4–43.5) | >0.05 |

| BFM (kg) | 34.2 (18.9–53.4) | 34.5 (16.8–63.4) | >0.05 |

| BFFM (kg) | 55.4 (46.3–80.9) | 61.6 (39.5–84.9) | >0.05 |

| TBW (kg) | 40.6 (33.9–59.2) | 45.1 (28.9–62.2) | >0.05 |

| WC (cm) | 109 (96–127) | 103 (78–124) | >0.05 |

| VFI | 15 (11–21) | 13 (5–24) | >0.05 |

| Liver markers | |||

| CAP (dB/m) | 337 (255–375) | 288 (216–400) | 0.025 |

| FLI | 86 (30–99) | 76 (7–99) | >0.05 |

| LSM (kPa) | 6.7 (1.5–9.9) | 5.9 (3.3–11.9) | >0.05 |

| ALT (U/l) | 42 (12–118) | 38 (16–84) | >0.05 |

| AST (U/l) | 26 (10–68) | 24 (10–121) | >0.05 |

| AP (U/l) | 75 (48–106) | 74 (37–159) | >0.05 |

| γ-GT (U/l) | 47 (17–93) | 32 (7–335) | >0.05 |

| PChE (kU/l) | 11.3 (7.9–17.0) | 10.4 (6.6–15.0) | >0.05 |

| Metabolic markers | |||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 115 (63–232) | 86 (68–156) | <0.001 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 152 (60–273) | 122 (65–419) | >0.05 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 210 (149–258) | 220 (147–303) | >0.05 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 139 (78–184) | 142 (84–226) | >0.05 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 50 (29–82) | 51 (33–110) | >0.05 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.4 (4.6–8.5) | 6.0 (2.9–8.6) | >0.05 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 131 (110–175) | 138 (110–175) | >0.05 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 87 (79–175) | 93 (74–125) | >0.05 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BFFM, body fat free mass; BFM, body fat mass; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FLI, fatty liver index; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; N, number; PChE, pseudocholinesterase; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TBW, total body water; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VFI, visceral fat index; WC, waist circumference.

Significant P values are highlighted in bold.

Metabolic effects

At baseline, over half of the cohort (60.0%) presented with TC concentrations ≥200 mg/dl. LDL cholesterol concentrations were above 130 mg/dl in 35 (58.6%) patients, and 22 (36.7%) patients had increased TG levels ≥150 mg/dl. After the dietary intervention, all lipid parameters decreased by one-third to a quarter apart from HDL cholesterol, which reduced by 13.0% (all P<0.001; Table 2). Specifically, a reduction of 17.1% for HDL cholesterol was noted in 46 patients, whereas 13 patients improved by 9.1% and one case remained stable. Most importantly, LDL cholesterol levels decreased by 25.3%, which corresponds to an absolute change of 32.5 mg/dl. The reduction occurred in 54 patients (90.0%).

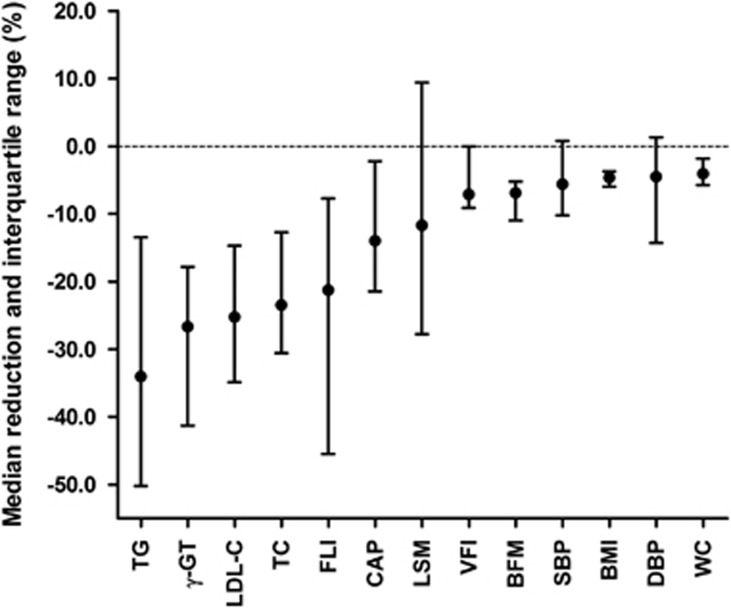

Overall, glucose levels decreased significantly by 7.1% (P<0.001). A positive change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure of −5.6 and −4.5% (both P≤0.001) was observed. The median reductions of key parameters assessed during the study are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of significant reductions of key parameters assessed during the dietary intervention. The values are displayed as medians, interquartile range, and ordered based on the extent of reduction. BFM, body fat mass; BMI, body mass index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FLI, fatty liver index; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VFI, visceral fat index; WC, waist circumference.

DISCUSSION

The aims herein were to simultaneously and non-invasively monitor liver and body fat composition in patients with NAFLD participating in a short-term dietary program, and to avail of CAP to assess dynamic changes in liver fat. After a 14-day hypocaloric high-fiber, high-protein diet, an absolute CAP reduction of 47 dB/m and a relative decrease of 14.0% were achieved. This was accompanied by a significant weight loss of 4.6%, of which almost two-thirds (61.9%) was loss of body fat mass. To our knowledge, this is the first study to monitor rapid changes in hepatic steatosis using CAP, which represents a patient-friendly non-invasive tool.

The results are in line with previous smaller studies using other methodologies to assess changes of liver phenotypes after dietary interventions. According to the AASLD guidelines, a reduction of body weight of at least 3–5% through a hypocaloric diet alone or together with increased physical activity is recommended for ameliorating steatosis.1 Colles et al.32 studied a very low-calorie diet (680 kcal/day) for 12 weeks in 32 morbidly obese patients. Body weight was reduced by 10.6% (14.8 kg), and liver volume assessed by computer tomography decreased by 18.7% (0.56 l). Interestingly, after 2 weeks, 80% of the overall decrease in liver volume was detected, whereas body weight improved steadily throughout.32 We did not observe a significant association between the extent of weight loss and improvement of liver phenotypes, as reported by others,18, 33 which might be related to less drastic changes in body fat mass (Figure 3). Some of the previously reported studies compared overall weight loss and BMI reductions only rather than compartmental changes of body composition. As the interventions were significantly longer, they may have resulted in greater changes of fat mass and corresponding liver-specific effects.18, 33

In addition to CAP reductions and weight loss, the dietary modification assessed herein also resulted in metabolic improvements, particularly those related to the metabolic syndrome. Besides the expected reduction in triglycerides, the reduction of LDL cholesterol levels by 33 mg/dl after 14 days is remarkable, especially in comparison to a meta-analysis of 174,000 patients, which reported a decrease of 42.5 mg/dl after 1 year of statin therapy.34 Another meta-analysis on dietary fiber reported a reduction of LDL cholesterol of 2.21 mg/dl for each 1 g of soluble fiber per day,35 which is reflected in our study with a daily intake of 14 g soluble fiber. HDL cholesterol levels decreased, which has previously been reported during acute weight loss, however HDL subsequently increased in the weight maintenance phase.36, 37, 38 Brinton et al.39 suggested that the reduction in HDL cholesterol might be associated with lower HDL apolipoprotein transport rates, and Aminian et al.40 observed a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity by up to 50% during caloric restriction. Once weight stabilized, HDL cholesterol metabolism reversed and led to increased HDL cholesterol concentrations above the pre-intervention levels.40

The diet given to patients as part of a specifically designed weight loss program contains ingredients known to be potentially beneficial for the liver, including omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids,41 l-carnitine,42 choline,43 β-glucan,44 inulin,45 and taurine.46

A limitation of this study is that we were unable to determine if, and to what extent, these ingredients contributed to the overall effects of liver fat reduction, as compared to the overall effects of the caloric restriction and concomitant weight reduction. Moreover, the significant improvements observed after 14 days do not afford the opportunity to evaluate the liver-specific long-term effects of the diet. Although several key parameters of the metabolic syndrome improved, we did not specifically assess the effect of the diet on insulin resistance.

Shen et al.47 studied the effect of a lifestyle modification program in NAFLD patients and observed that patients who carry the PNPLA3 mutation p.I148M showed a better response as compared to patients with wild-type alleles.47 Although, the current data on genetic associations in our study are hampered by sample size, we also note that hepatic response was observed in all homozygous carriers of the PNPLA3 risk allele, which should be further evaluated as personalized biomarker for a response to the dietary regimen.

Recent recommendations from a joint AASLD–FDA workshop pointed out that the use of elastography in subjects with NASH has not been explored in great detail, and that non-invasive measures should be included as secondary or exploratory endpoints in current trials.48 Our study results illustrate that CAP might represent a reliable alternative for monitoring hepatic steatosis in research and clinical settings.23, 49

In conclusion, the 14-day hypocaloric high-fiber, high-protein diet reduced CAP, and hence hepatic steatosis simultaneously to improvements in parameters of the metabolic syndrome. We demonstrated that improvements in hepatic fat contents can be observed after a couple of weeks only, which highlights the possibility for dynamic short-term modulation of liver fat. Whether such a program provides long-term benefits for these patients should be substantiated, but extent and rate of liver fat reduction set the benchmark for pharmacological treatment. Regardless, CAP provides a convenient and patient-friendly method to assess lipid turnover during lifestyle and dietary interventions to combat NAFLD.

Study Highlights

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients for taking part in this study as well as Agathe Buchheit, Silke Schirra, Marita Lieblang, and Beate Linnebach for collecting blood samples. Anita Arslanow is grateful to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) for the travel bursary to attend the International Liver Congress 2015. The results were, in part, presented at the 50th Annual Meeting of EASL in Vienna 2015, acknowledged with an EASL prize for the best poster presentation, and published in abstract form in the JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY, Vol. 62, Suppl. 2, p. S738. This work is part of the PhD thesis of Anita Arslanow.

Guarantor of the article: F. Lammert, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions: After designing the study by A. Arslanow, F. Lammert, and C. S. Stokes; A. Arslanow, M. Teutsch, and H. Walle recruited patients; A. Arslanow collected the data and together with F. Lammert and C. S. Stokes analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript, which was then critically revised by all authors. The final draft submitted has been approved by all authors.

Financial support: This work was supported, in part, by Bodymed, which awarded an unrestricted grant to Saarland University (A. Arslanow and F. Lammert). M. Teutsch is employed by and H. Walle is a stockholder of Bodymed. Bodymed did not have any influence on study design and data analysis; the work was independent of the financial support. C. S. Stokes and F. Grünhage have nothing to declare.

Potential competing interests: None.

References

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 2012; 55: 2005–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than NN, Newsome PN. A concise review of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atherosclerosis 2015; 239: 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M et al. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol 2013; 58: 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H et al. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol 2010; 53: 372–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R, Schork N, Chen CH et al. Heritability of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis based on a prospective twin study. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 1784–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loria P, Lonardo A, Anania F. Liver and diabetes. A vicious circle. Hepatol Res 2013; 43: 51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 1461–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickel F, Hampe J, Trepo E et al. PNPLA3 genetic variation in alcoholic steatosis and liver disease progression. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2015; 4: 152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslanow A, Stokes CS, Weber SN et al. The common PNPLA3 variant p.I148M is associated with liver fat contents as quantified by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP). Liver Int 2016; 36: 418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk M, Grünhage F, Zimmer V et al. Variant adiponutrin (PNPLA3) represents a common fibrosis risk gene: non-invasive elastography-based study in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol 2011; 55: 299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Patman GL, Leathart JB et al. Carriage of the PNPLA3 rs738409 C >G polymorphism confers an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2014; 61: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a systematic review. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufe S, Engeli S, Kast P et al. Randomized comparison of reduced fat and reduced carbohydrate hypocaloric diets on intrahepatic fat in overweight and obese human subjects. Hepatology 2011; 53: 1504–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D et al. Reversal of nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis, hepatic insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia by moderate weight reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005; 54: 603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo P, Bugianesi E, Bjornsson ES et al. Simple noninvasive systems predict long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 782–789 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P, Younossi ZM. Abdominal ultrasound for diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2716–2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NS, Doycheva I, Peterson MR et al. Effect of weight loss on magnetic resonance imaging estimation of liver fat and volume in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 561–568 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51: 121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tendler D, Lin S, Yancy WSJr et al. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52: 589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terjung B, Lemnitzer I, Dumoulin FL et al. Bleeding complications after percutaneous liver biopsy. An analysis of risk factors. Digestion 2003; 67: 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A et al. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 1898–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzigotti A. Getting closer to a point-of-care diagnostic assessment in patients with chronic liver disease: controlled attenuation parameter for steatosis. J Hepatol 2014; 60: 910–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasso M, Beaugrand M, de Ledinghen V et al. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP): a novel VCTE guided ultrasonic attenuation measurement for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis: preliminary study and validation in a cohort of patients with chronic liver disease from various causes. Ultrasound Med Biol 2010; 36: 1825–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Association for Study of Liver, Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado. EASL-ALEH clinical practice guidelines: non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol 2015; 63: 237–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB et al. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines For Use In Primary Health Care, 2nd edn. World Health Organisation: Geneva 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Martens S et al. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2008; 134: 960–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39: S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L et al. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol 2006; 6: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ledinghen V, Vergniol J, Foucher J et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of liver steatosis using controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and transient elastography. Liver Int 2012; 32: 911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J et al. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles SL, Dixon JB, Marks P et al. Preoperative weight loss with a very-low-energy diet: quantitation of changes in liver and abdominal fat by serial imaging. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) CollaborationFulcher J, O'Connell R et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2015; 385: 1397–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW et al. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69: 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasankari T, Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K et al. Reduced oxidized low-density lipoprotein after weight reduction in obese premenopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazet IM, de Craen AJ, van Schie EM et al. Sustained beneficial metabolic effects 18 months after a 30-day very low calorie diet in severely obese, insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 77: 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert A, Kratzsch J, Selhorst J et al. Clinical benefit of a short term dietary oatmeal intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes and severe insulin resistance: a pilot study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2008; 116: 132–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton EA, Eisenberg S, Breslow JL. A low-fat diet decreases high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels by decreasing HDL apolipoprotein transport rates. J Clin Invest 1990; 85: 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminian A, Zelisko A, Kirwan JP et al. Exploring the impact of bariatric surgery on high density lipoprotein. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11: 238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro H, Tehilla M, Attal-Singer J et al. The therapeutic potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Nutr 2011; 30: 6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaguarnera M, Gargante MP, Russo C et al. l-carnitine supplementation to diet: a new tool in treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis–a randomized and controlled clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1338–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin KD, Zeisel SH. Choline metabolism provides novel insights into nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its progression. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2012; 28: 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Huang CN, Yeh DM et al. Oat prevents obesity and abdominal fat distribution, and improves liver function in humans. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2013; 68: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brighenti F. Dietary fructans and serum triacylglycerols: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr 2007; 137: 2552S–2556S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile CL, Nivala AM, Gonzales JC et al. Experimental evidence for therapeutic potential of taurine in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011; 301: R1710–R1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Wong GL, Chan HL et al. PNPLA3 gene polymorphism and response to lifestyle modification in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 30: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal AJ, Friedman SL, McCullough AJ et al. Challenges and opportunities in drug and biomarker development for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: findings and recommendations from an American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-U.S. Food and Drug Administration Joint Workshop. Hepatology 2015; 61: 1392–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi KQ, Tang JZ, Zhu XL et al. Controlled attenuation parameter for the detection of steatosis severity in chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29: 1149–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]