Abstract

Persistent pain is experienced by more than 50% of persons who sustain a traumatic brain injury (TBI), and more than 30% experience significant pain as early as 6 weeks after injury. Although neuropathic pain is a common consequence after CNS injuries, little attention has been given to neuropathic pain symptoms after TBI. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies in subjects with TBI show decreased brain concentrations of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), a marker of neuronal density and viability. Although decreased brain NAA has been associated with neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury (SCI) and diabetes, this relationship has not been examined after TBI. The primary purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that lower NAA concentrations in brain areas involved in pain perception and modulation would be associated with greater severity of neuropathic pain symptoms. Participants with TBI underwent volumetric MRS, pain and psychosocial interviews. Cluster analysis of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory subscores resulted in two TBI subgroups: The Moderate Neuropathic Pain (n = 17; 37.8%), with significantly (p = 0.038) lower insular NAA than the Low or no Neuropathic Pain group (n = 28; 62.2%), or age- and sex-matched controls (n = 45; p < 0.001). A hierarchical linear regression analysis controlling for age, sex, and time post-TBI showed that pain severity was significantly (F = 11.0; p < 0.001) predicted by a combination of lower insular NAA/Creatine (p < 0.001), lower right insular gray matter fractional volume (p < 0.001), female sex (p = 0.005), and older age (p = 0.039). These findings suggest that neuronal dysfunction in brain areas involved in pain processing is associated with pain after TBI.

Key words: : biomarkers, central pain, MRI spectroscopy, N-acetylaspartate, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Approximately 2.5 million people sustain a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the United States each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics.1 It has been estimated that persistent pain of various origins may develop in more than 50% of persons with TBI.2 An early study by Lahz and Bryant3 reported that persistent pain was experienced by 58% of those sustaining mild TBI and 52% of those sustaining moderate or severe TBI. Although the most common pain problems after TBI were persistent headaches, 15–28% experienced neck, shoulder, back, upper and lower limb pains. Similar observations were made by Mittenberg and associates,4 who reported a 59% prevalence of headache as part of the post-concussion syndrome.

Together with reduced well-being and social participation, the presence of pain post-TBI is a significant negative predictor of employment5 and return to productivity.6 Importantly, persistent pain after TBI is associated with poorer long-term health-related quality of life.7,8 A recent longitudinal study suggested that both pain and depression are common and often co-occurring after TBI.9 These investigators also found that although the overall frequencies of both comorbidities decreased over time, the association between pain and depression strengthened with time after injury.

Neuroimaging research suggests that pain is processed in a network of somatosensory cortices (S1, S2), insular cortex (IC), limbic (anterior cingulate cortex; ACC), and associative (prefrontal cortex; PFC) structures that receive multiple inputs from nociceptive pathways.10 Both human and animal research show that chronic neuropathic pain causes reorganization and functional changes in both cortical and subcortical structures—e.g., the medial pre-frontal cortex,11–13 thalamus,14 and anterior cingulate cortex.15 Changes in these areas are also associated with cognitive and emotional factors common in patients with chronic pain, such as anxiety and depression,16 problems in emotional decision making,17 and working memory.18 Thus, trauma-induced dysfunction in these areas may contribute both to the development and severity of pain.

The development of mechanism-based treatments for chronic pain in general can be facilitated by the identification of reliable clinical pain phenotypes and/or surrogate biomarkers of specific pain mechanisms.19 Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) is a noninvasive technique that detects and quantifies metabolite concentrations in the brain and has been shown to be valuable in the identification of objective biomarkers,20 thus enhancing our understanding of pain mechanisms. N-acetylaspartate (NAA), a marker of neuronal density and viability that can be quantified by MRSI, is a common brain metabolite that is highly concentrated in neurons. A decrease in NAA concentration therefore suggests either loss of neurons or neuronal dysfunction.21 Several magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies in subjects with mild TBI have demonstrated decreased NAA,21–24 as well as normalization of NAA levels in parallel with clinical improvement.25

Although reduced levels of NAA have been demonstrated in neurodegenerative conditions such as multiple sclerosis,26 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related dementia,27 Parkinson disease,28 and Alzheimer disease,29,30 research has also demonstrated a significant relationship between reduced brain concentrations of NAA and persistent pain (for a recent review, see Chang and colleagues20). For example, lower thalamic concentrations of NAA have been demonstrated in persons with heterogeneous chronic pain,10 heterogeneous chronic neuropathic pain,31 and in neuropathic pain associated with diabetes32 and with spinal cord injury (SCI).33,34 Moreover, reduced thalamic NAA/Creatine (Cr) was demonstrated in migraine patients with aura and in trigeminal neuralgia.35

In our previous research,33 MRSI was used to assess thalamic metabolite concentrations in persons with SCI who experienced chronic neuropathic pain. In that study, higher ratings of pain intensity were significantly correlated with lower NAA concentrations. In addition, the levels of NAA were significantly lower in participants with neuropathic pain compared with those with SCI and no neuropathic pain. The low levels of NAA were hypothesized to indicate amplification of the pain signal by either dysfunction or loss of inhibitory neurons. Based on this study and on the results from two other magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in chronic back pain,14,36 it is reasonable to assume that a TBI may cause specific changes in the brain leading to the development of persistent pain.

Moreover, neuroimaging studies have shown that changes in brain morphology related to gray matter (GM) density often accompany chronic pain conditions,37–43 particularly in brain areas related to perception and modulation of pain. Importantly, such changes have also been associated with the perceived magnitude of pain.44–46

Because of the high prevalence of neuropathic pain47 and its relationship with brain NAA brain biomarkers in another neurotrauma population, i.e., SCI,33,34 this relationship was the primary focus in the present study of subjects with TBI. Specifically, the main purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between the presence of neuropathic pain symptoms, pain severity (PS), and NAA in brain areas known to be involved in the processing and modulation of pain among individuals with subacute TBI and, moreover, to examine the relationship between pain-relevant NAA concentration and white matter (WM)/GM fractional volumes. It was hypothesized that NAA levels would be lower in persons with more severe neuropathic pain symptoms compared with those with mild or no pain subsequent to TBI.

Methods

General study design

The present study included data from 45 subjects with mild to severe TBI and 45 age- and sex-matched control subjects with no TBI. During a first 2-h session, all subjects underwent imaging (MRSI) and completed a neuropsychological evaluation. Only the control subjects recruited in the latter part of the study (n = 21) were assessed with respect to cognitive function, anxiety, depression, and apathy. During a second 1-h session, only TBI subjects completed a structured pain history interview including pain-relevant psychosocial measures. The data presented in this article represent a subset of data focused on pain and are part of a larger study approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine in Miami, Florida.

Participants

Fifty-one subjects with a mild to severe TBI were recruited from persons presenting to the Jackson Memorial Hospital Emergency Department or admitted to Jackson Memorial Hospital after a closed head injury. Further inclusion criteria included a modified Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6 to 15 on admission, a loss of consciousness, and standard MRI prescreening clearance. The GCS score at the time of admission to the trauma center, loss of consciousness as recorded by paramedic personnel and reported to the trauma center or at the time of admission to the trauma center, cause of injury (e.g., motor vehicle accident, fall), medical history, and medication data were taken from the subjects' medical chart.

GCS scores were used to classify the subject as having mild (between 13 and 15), moderate (between 9 and 12), or severe TBI (between 3 and 8). Subjects with a history of previous TBI, psychiatric illness, or neurological disease, an inability to undergo a 3 Tesla (3T) MRI scan or neuropsychological evaluation were excluded.

Of this sample, two subjects withdrew and four did not provide useful MRS data, because of motion artifacts, or other essential data. Of the remaining 45 subjects, the modes of injury were 25 motor vehicle accidents as occupants, 9 assaults (three struck on the head with an object), 6 struck by a motor vehicle while a pedestrian or swimmer, 3 struck by objects not involving an assault, and 2 falls.

All control (non-TBI) subjects included in this study were recruited from the same local community as that of the subjects with TBI. We used the same standards to clear these subjects for MRI. Exclusion criteria applied to this group included previous head injury or surgery, history of epilepsy or a seizure disorder, neurodegenerative (e.g., Alzheimer, Parkinson) and neurological (e.g., cancer, stroke, multiple sclerosis) diseases, regular use of hard drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine, heroin), current and long-term heavy alcohol use, taking medication for a psychiatric problem (e.g., depression), chronic liver disease, and HIV+ status.

MRI and MRS

MR data were acquired at 3T (Siemens, Tim-Trio), using eight-channel phased-array detection. The protocol included a T1-weighted MRI with 1-mm isotropic resolution (magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo sequence, echo time [TE]/repetition time [TR] = 4.43/2150 msec, 160 slices). Volumetric MRSI data were obtained using a spin-echo acquisition with selection of a 135-mm slab covering the cerebrum and cerebellum, echo-planar readout with 1000 spectral sample points, and a spectral bandwidth of 1250 Hz, TR/TE = 1710/70 msec, spatial sampling of 50 × 50 × 18 points over 280 × 280 ×180 mm3, and an acquisition time of 26 min.

Data were processed in a fully automated manner using the MIDAS package48 to provide metabolite images for NAA, Cr, choline, and their ratios, with a 1 mL resultant voxel volume. Processing included signal intensity normalization of individual metabolite images to institutional units (IU) using tissue water as a reference, and correction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) partial volume based on tissue segmentation of the T1-weighted MRI. All images were then spatially registered to a T1-MRI template in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space49 and interpolated to 2-mm isotropic voxels. Additional details of the processing have been reported previously.50

The T1-MRI images were segmented into WM, GM, and CSF maps using FSL/FAST,51 which were converted to SI resolution and, together with the spectral-fit metabolite maps, were registered to a T1-MRI template in MNI space.49 A modified atlas52 in the MNI space was then used to obtain mean values of the MRS measures over left and right sides of the insula, anterior, mid-, and posterior cingulum, and the thalamus. For cortical regions, the relative GM volume fraction (GMvol/[GMvol+WMvol+CSFvol]) was also calculated to determine the relationship between decreased NAA concentrations and GM because NAA concentrations are higher in GM.53

Neuropsychological examination

The Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination, 2nd edition, standard version (MMSE-2)54 is a brief mental status screen that assesses Orientation, Registration and Recall, Attention and Calculation, Language (Naming, Repetition, Three-Stage Command), Reading, Writing, and Copying. It is a widely used, well validated, and reliable measure for individuals 18 years of age and older. The MMSE-2 was used to detect gross cognitive impairments. A score ≥25 (out of 30) was considered normal cognition. The cut score is adjusted for educational attainment and age.

Assessment of pain and psychosocial factors

Demographic factors and pain history

In addition to standard demographic information—e.g., age, sex, mode of injury etc.—a standard pain history with an anatomical drawing was used to obtain information regarding the subject's pain experience (i.e., each pain's location, onset relative to TBI, temporal pattern, quality, severity, and any medications taken for relief). In addition to the pain history, the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI)55 and the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI)56 were obtained. All measures were obtained via interviews by trained staff.

NPSI

The NPSI55 assesses average severity in the previous 24 h of 10 descriptors associated with neuropathic pain using a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale. These reflect spontaneous ongoing and paroxysmal pain, evoked pain (i.e., mechanical and thermal allodynia/hyperalgesia), and dysesthesia/paresthesia. Subscores are calculated to allow discrimination and quantification of five distinct and clinically relevant dimensions of neuropathic pain.

A total intensity score can also be calculated by summation of the 10 descriptor responses (maximum score of 100); the two temporal items are not scored. The five subscales are scored by taking the arithmetic mean of the subscale's constituent item responses—e.g., the evoked pain subscore is the mean of the three severities of pain that are provoked or increased by: (1) brushing, (2) pressure, and (3) contact with cold on painful areas (maximum subscore of 10). The NPSI has been shown to be both valid and reliable.55 The NPSI subscores were used to cluster subjects into subgroups.

MPI

The MPI56 is a comprehensive psychometric instrument designed to assess pain and a range of self-reported behavioral and psychosocial factors associated with chronic pain. Responses are given on a numerical rating scale ranging from 0 to 6. The MPI consists of three sections: Pain Impact, Perceived Social Support, and Activities, consisting of 52 scored items from which 12 subscales are obtained—e.g., the Pain Impact section has 20 items and 5 subscales: PS, Life Interference (LI), Affective Distress (AD), Life Control, and Support. All subscales are scored by taking the arithmetic mean of the constituent item responses (maximum subscore of 6). For example, the PS subscore is the mean of three items relating to: (1) present overall severity, (2) average overall severity in the past week, and (3) suffering due to pain.

Three of the MPI Pain Impact subscales were used to compare potential neuropathic pain subgroups: PS, LI, and AD. These specific subscales were selected to reflect the key domains recommended by the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) group.57

Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II)

The BDI-II58 assesses the severity of depressive symptoms in adolescents and adults based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, criteria. The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report multiple-choice questionnaire that asks subjects to rate depressive symptoms on a scale of 0 to 3 based on how they have been feeling over the past 2 weeks, with increasing scores reflecting greater symptomatology. This instrument is widely used in clinical and research settings as a brief screen for depression and has been validated for use in a number of populations, including college students,58 clinically depressed outpatients,58,59 and those with neuropathic pain.60

Internal consistencies (0.86 for psychiatric patients and 0.81 for nonpsychiatric patients) are good and test-retest reliability is greater than 0.60.61 Scores over 13 indicate the presence of clinically significant symptoms. Scores ranging between 14 and 19 are rated as mild depression, 20–28 as moderate depression, and scores between 29 and 63 are rated as severe depression. We used the BDI-II as an external validator to confirm the validity of the TBI neuropathic subgroups.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The BAI62 is a 21-item self-report multiple-choice questionnaire that asks subjects to rate their anxiety symptoms based on how they have been feeling over the past week. The BAI was designed to assess emotional, physiological, and cognitive symptoms of anxiety. It has been shown to be a useful screening measure for anxiety and able to discriminate between depressive and anxious symptoms. Similar to the BDI-II, it uses a 0 to 3 rating scale, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of anxiety. Scores over 8 are considered to be clinically significant with 8–15 rated as mild anxiety, 16–25 as moderate anxiety, and 26–63 as severe anxiety. The BAI is widely used in both adolescents63 and adults64 including those with intellectual disabilities.65 The internal consistency is excellent (α = .92) with test-retest reliability (r = 0.75).66

Apathy Evaluation Scale, self-rated version (AES-S)

The AES-S67 is a self-rating measure of apathy symptoms consisting of 18 questions in which a person describes his or her thoughts, feelings, and actions during the past 4 weeks. Items are scored as “Not at all” (1 point), “Slightly” (2 points), “Somewhat” (3 points), and “A lot” (4 points). The AES-S may be used in adolescent and adult populations. Cut scores vary between studies depending on the clinical sample; however, it is generally accepted to be two standard deviations above the mean—i.e., 36.5–37.5, for the self-rated version.67,68

Statistical analysis

A two-step cluster procedure was used to define homogeneous subgroups or “clusters” inherent in the data set based on the NPSI subscores. The two-step clustering procedure has been previously used and described in more detail in previous work.69 The number of clusters was automatically determined by the IBM SPSS Statistics 22 for Windows default criterion (Schwarz Criterion).70 Once the number of clusters was determined, these were compared with respect to NPSI subscores, NAA/Cr concentrations, pain measures, demographics, and psychological/neuropsychological measures to define and externally validate the clusters.

Independent t tests, chi-squares, and Pearson correlations were used to determine pairwise differences and correlations. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between the NAA and PS and the potential influence of age, sex, days since injury, and insular GM volume. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 22 for Windows. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and injury characteristics

The study sample consisted of 45 people with mild to severe closed head TBI who were compared with 45 age- and sex-matched controls. The average age of the TBI cohort was 27.9 ± 8.27 years, and 30 (66.7%) were males. The control subjects were on average 28.7 ± 7.69 years old, and 34 (75.6%) were males. The average GCS and MMSE-2 scores for the TBI subjects were 13.2 ± 2.85 and 27.3 ± 4.20, respectively.

Pain location and quality

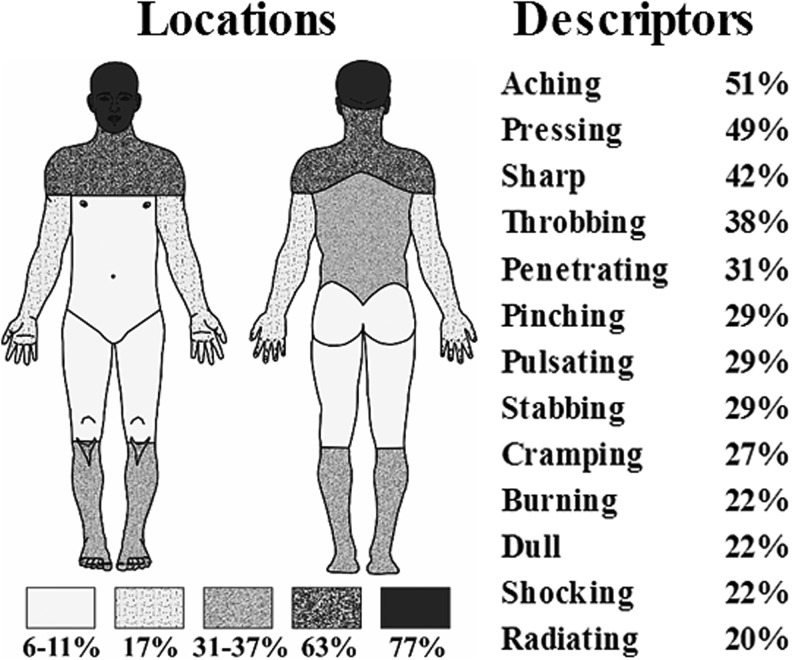

Of the 45 subjects with mild to severe closed TBI, 35 (77.8%) reported experiencing pain (Fig. 1). Although pain was located in the head region in 77% of the sample, other common pain locations were the neck/shoulders (63%), back (37%), and lower legs (31%). The most commonly reported pain qualities were aching, pressing, sharp, and throbbing pain. Thirty subjects with TBI and pain (85.7%) reported experiencing more than one type of pain.

FIG. 1.

The figure shows the frequencies of locations and pain descriptors reported by subjects (n = 35).

Cluster analysis of TBI subjects based on neuropathic pain symptoms

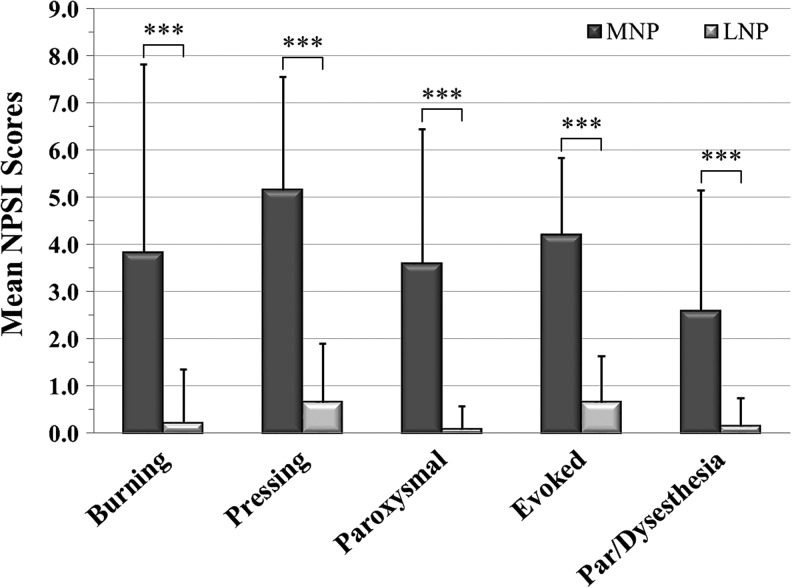

The frequencies of persons reporting a symptom for each NPSI subscale were: (1) burning (superficial) spontaneous pain (n = 10, 22.2%); (2) pressing (deep) spontaneous pain (n = 23, 51.1%); (3) paroxysmal pain (n = 15, 33.3%); (4) evoked pain (n = 27, 60.0%); (5) paresthesia/dysesthesia (n = 13, 28.9%); and (6) any NPSI symptom (n = 29, 64.4%). Persons who did not report any pain symptom on the NPSI scored a “0.” A two-step cluster analysis of the five NPSI subscale scores resulted in two clusters/groups, and these were labeled based on their cluster characteristics: moderate neuropathic pain severity (MNP; n = 17; 37.8%) with significantly greater NPSI scores (p < 0.001) than the low or no neuropathic pain severity (LNP (n = 28; 62.2%; Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The figure shows the subgroup Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI) subscores, mean ± standard deviation, (i.e., the burning [superficial] spontaneous pain, pressing [deep] spontaneous pain, paroxysmal pain, evoked pain, and the paresthesia/dysesthesia subscales) for each of the two pain subgroups, the moderate neuropathic pain (MNP; n = 17; 37.8%) and the low or no neuropathic pain (LNP; n = 28; 62.2%). ***p ≤ 0.001.

Comparisons between the MNP and the LNP and control groups

Age and sex

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc correction indicated that the average age of the MNP subgroup was significantly higher than the LNP subgroup (31.9 ± 9.0 and 25.4 ± 6.9 years, respectively, p = 0.025). The average age of the control subjects was 28.7 ± 7.7 years, which was not significantly different than either the MNP or the LNP subgroups. The MNP subgroup included 5 women and 12 men, the LNP subgroup 6 women and 22 men, and the control group 15 women and 30 men. There was no significant (χ2 = 1.194; p = 0.551) difference between the three groups with respect to sex distribution.

Days since injury and GCS

On comparison of the two TBI pain subgroups, MNP and LNP, the time since injury (at the time of assessment) did not differ significantly (37.6 ± 19.8 days and 48.5 ± 27.8 days, respectively, t = −1.419; p > 0.05). Fifteen (88.2%) of the MNP subjects (n = 17) had GCS scores in the mild range (13–15), one (5.88%) in the moderate (9–12), and one (5.88%) in the severe range (3–8). Twenty (71.4%) of the subjects in the LNP subgroup (n = 28) had GCS scores in the mild range, four (14.3%) in the moderate, and four (14.3%) in the severe category. The average GCS scores did not significantly differ between the MNP and the LNP subgroups (13.8 ± 2.27 and 12.9 ± 3.14, respectively, t = 1.15; p > 0.05).

Psychosocial and cognitive factors

An ANOVA comparing the two TBI subgroups and a subset of the control group (n = 21) showed that the MMSE-2 scores were significantly different between subgroups (F = 8.752; p < 0.001) with the MNP subgroup scoring significantly lower (25.1 ± 6.1) than both the LNP (28.7 ± 1.3; p < 0.001) and the control groups (29.1 ± 1.1; p = 0.002). Four subjects (23.5%) in the MNP subgroup scored below the 25 cut score compared with none in the LNP or control groups.

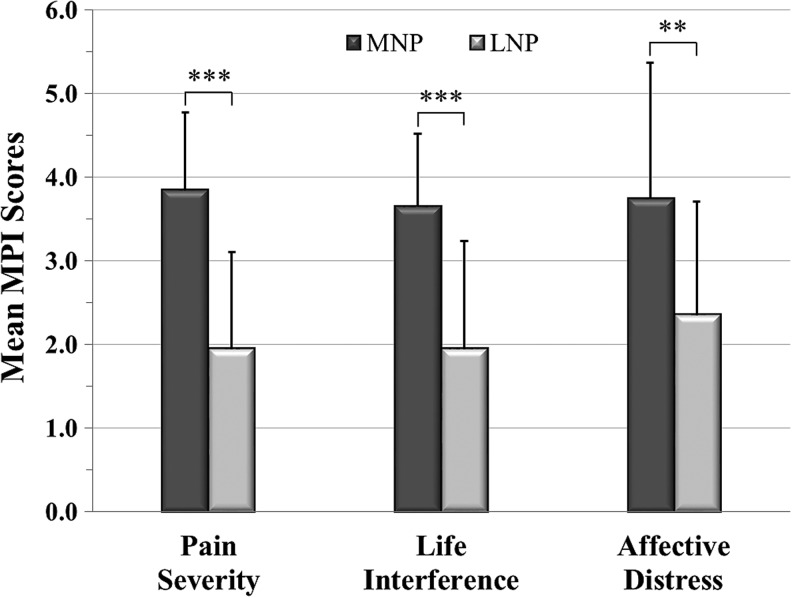

To externally validate the two clusters, they were compared on three subscales of the MPI: PS, LI, and AD (Fig. 3). All MPI subscale scores were significantly higher in the MNP subgroup, supporting the appropriateness of the two cluster assignments.

FIG. 3.

The figure shows the subgroup Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) subscores, mean ± standard deviation, (i.e., Pain Severity, Life Interference and Affective Distress) for the moderate neuropathic pain (MNP) (n = 17) and the low or no neuropathic pain (LNP) subgroups (n = 18). **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

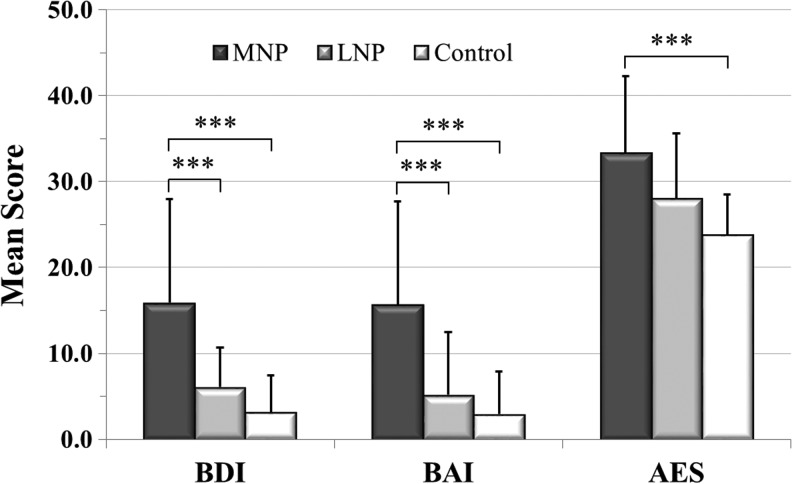

ANOVAs with post hoc Tukey corrections comparing the two TBI subgroups and the subset of the control group (n = 21) showed significantly greater BDI-II and BAI average scores in the MNP group compared with the LNP and the control groups (Fig. 4). For the BDI-II, 43.8% of subjects in the MNP group scored 14 or above, indicating at least mild depressive symptoms, as opposed to 3.6% (n = 1) for the LNP and 4.8% (n = 1) of the control groups. For the BAI, 68.7% of the MNP group scored in a range of 8 or above, suggesting mild or greater anxiety symptoms. This is in contrast to 17.9% of the LNP and 9.5% of the control subjects.

FIG. 4.

The figure shows the subgroup Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) scores, mean ± standard deviation, for the moderate neuropathic pain (MNP) (n = 17), low or no neuropathic pain (LNP) (n = 28), and control (n = 21) groups. ***p ≤ 0.001.

The AES scores were higher in both the MNP and LNP subgroups compared with the control group (Fig. 4); however, only the MNP subgroup was significantly so (p = 0.001). The MNP subgroup's AES score was higher than that of the LNP, but not significantly so (p = 0.054). Twenty-five percent of the subjects in the MNP group scored in a range suggesting apathy (cutoff score 38) compared with 17.9% in the LNP and none in the control groups.

Brain metabolite ratios

In the comparisons analyses, the NAA/Cr ratio was used rather than the NAA concentration, because Cr is regarded as relatively constant in the human brain and therefore routinely used in ratios to evaluate levels of other metabolites. ANOVA comparisons of the NAA/Cr levels in the insula, the anterior, mid-, and posterior parts of the cingulate cortex, and the thalamus regions of interest (ROIs) indicated significant differences between groups in the right (F = 8.09; p < 0.001) and left insula (F = 8.53; p < 0.001) and the right (F = 7.25; p < 0.001) and left midcingulate cortex (F = 7.93; p < 0. 001), but not in the other regions—i.e., anterior and posterior cingulate cortices (F = 3.08; p > 0.5 and F = 0.16; p > 0.05) and the thalamus (F = 1.06; p > 0.05).

NAA/Cr ratios in the right and left sides of the insula and the midcingulate cortex were highly intercorrelated (r = 0.728; p < 0.001 and r = 0.916; p < 0.001, respectively). Therefore, data from the left and right sides of these two ROIs were averaged in further analysis.

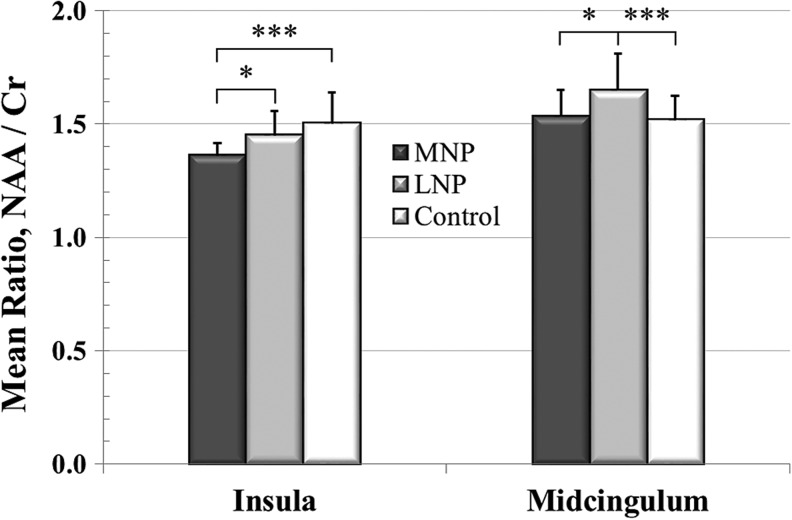

The post hoc analysis (Fig. 5) revealed significant differences between the MNP, LNP, and controls. The NAA/Cr levels in the insula were significantly lower in the MNP subgroup compared with the LNP subgroup (p = 0.038) and the control group (p < 0.001). The NAA/Cr levels in the midcingulate cortex were significantly lower (p = 0.013) in MNP compared with the LNP subgroup, but not significantly different from the control group.

FIG. 5.

The figure shows the group insula and midcingulum N-acetylaspartate/creatine (NAA/Cr) ratio, mean ± standard deviation, for the moderate neuropathic pain (MNP) (n = 17), low or no neuropathic pain (LNP) (n = 28), and control (n = 45) groups. *p ≤ 0.05, ***p ≤ 0.001.

To further elucidate the individual roles of insular NAA and Cr concentrations with respect to pain, two ANOVAs comparing the two TBI subgroups and the control group were performed. The overall ANOVAs indicated significant differences among groups for both NAA (F = 4.962; p = 0.009) and Cr (F = 12.468; p < 0.001). Post hoc Tukey tests indicated significantly lower insular NAA concentrations in the MNP (14625.5 ± 989.3 IU) compared with the LNP group (15354.3 ± 855.6 IU; p = 0.024), but not significantly different than the control group (14767.6 ± 865.4 IU).

With respect to Cr levels, the post hoc tests indicated that although the insular Cr levels were not significantly different between the MNP (10825.8 ± 648.1 IU) and the LNP (10809.8 ± 706.0 IU) subgroups, they both had significantly higher Cr levels (p < 0.001) than the control group (10075.8 ± 720.2 IU). These findings support previous research in that Cr levels are increased in persons with mild TBI, regardless of pain status, and also suggests that the Cr level, per se, is not be essentially related to PS.

Predicting the severity of pain

To further elucidate the relationship between severity of pain and insular NAA/Cr concentrations while controlling for potential confounders, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed in subjects who reported pain (n = 35). The insula was selected based on the significant differences in NAA/Cr concentrations between the two TBI subgroups and the control group. The PS subscore of the MPI was entered as the dependent variable and sex, age, and days since injury as a first step analysis (enter procedure) to control for these variables as potential confounders, the NAA/Cr metabolite concentrations and the GM fractional volumes in the left and right insula as a second step (forward procedure).

The analysis resulted in a highly significant model (r2 = 0.655; F = 10.995; p < 0.001) showing that greater pain severity was significantly predicted by lower levels of insular NAA/Cr (t = −4.74; p < 0.001), lower right insular fractional GM volume (t = −3.92; p < 0.001), female sex (t = 3.06; p = 0.005), and older age (t = 2.16; p = 0.039), while days since injury did not significantly contribute to the model. Because the fractional GM volume on the right side was significantly associated with PS in the hierarchical regression analysis, the pairwise relationships between PS and fractional volumes of GM and WM and CSF were investigated.

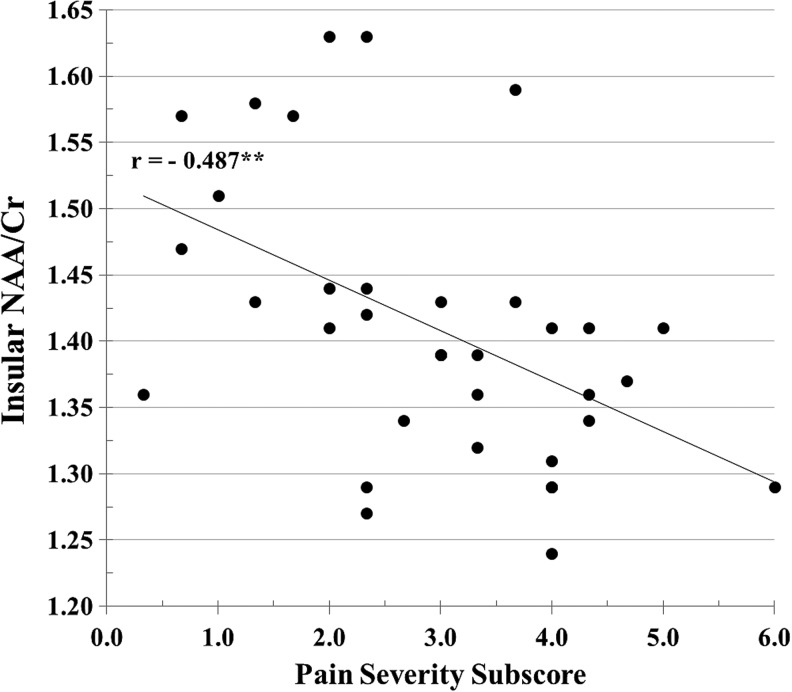

The scatterplot in Figure 6 shows the pairwise correlation between PS and insular NAA/Cr. Because a ratio does not specify which metabolite is specifically related to a variable, the relationship between insular NAA and Cr concentrations and PS were individually calculated. The insular NAA concentration was inversely significantly correlated with PS (r = −0.362; p = 0.033) consistent with the association between NAA/Cr ratio and PS, whereas the Cr concentration was not correlated (r = 0.081; p > 0.05) with PS. This analysis suggests that NAA is the primary metabolite related to PS rather than Cr.

FIG. 6.

The figure shows the significant inverse correlation between insular N-acetylaspartate/creatine (NAA/Cr) and the Pain Severity subscore of the Multidimensional Pain Inventory. **p < 0.01.

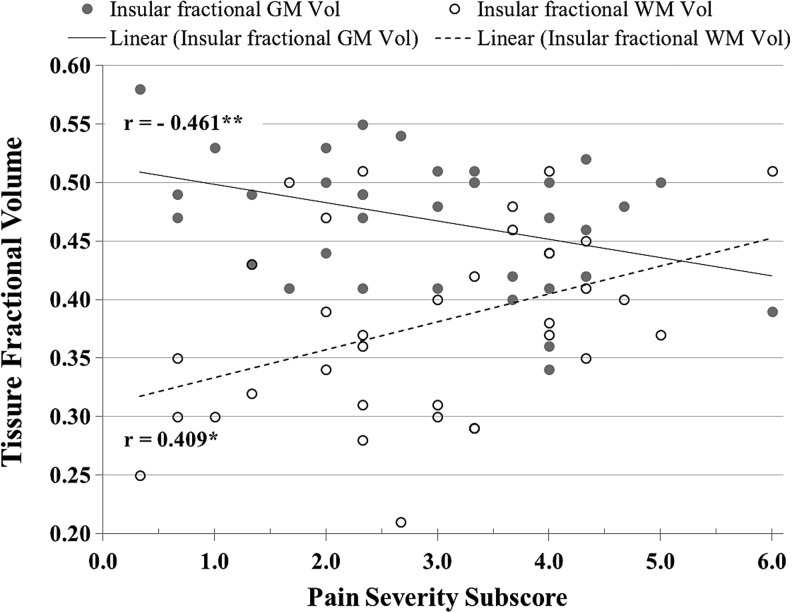

The pairwise relationship between fractional GM and WM volumes and PS is displayed in Figure 7. Data from CSF partial volume was not included in Figure 7 because it was not significantly associated with PS (r = 0.11; p = 0.52). While fractional GM volume was negatively correlated (r = −0.46; p = 0.005) with PS, WM fractional volume was positively correlated (r = 0.41; p = 0.015). This result suggests that with increasing PS, there is a corresponding decrease in GM and an increase in WM.

FIG. 7.

The figure shows significant correlations between the insular gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) fractional volumes of the traumatic brain injury group (n = 35) and the Pain Severity subscore of the Multidimensional Pain Inventory. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Persistent pain after a TBI is a prevalent clinical problem that is linked to reduced quality of life and overall emotional well-being. A large proportion of the TBI subjects in the present study (n = 35; 77.8%) experienced several different types of pain with clearly distinguishable features in different body areas including headache, at an average of 44.4 ± 25.4 days after injury. Although the pain conditions experienced by the subjects in the present study should be regarded as subacute rather than chronic, early pain appears to precede the development of neuropathic pain in a substantial proportion of subjects with TBI.71 This concurs with a systematic review showing the prevalence of chronic pain after TBI is about 50%.2

A recent study including 1716 persons who had sustained mild TBIs after motor vehicle accidents demonstrated that 30% reported clinically significant pain in more than three body areas at 6 weeks after injury.72 After 1 year, this cohort still reported significant (≥5 on an Numeric Rating Scale of 0–10) headache (n = 207, 18.6%), neck pain (n = 283, 25.4%), midback pain (n = 87, 7.8%), and low back pain (n = 209, 18.8%). Thus, a substantial proportion of the people can be expected to develop different types of chronic pain (including nociceptive and neuropathic) after a TBI.

In the present study, 31 TBI subjects (68.9%) experienced one or several pain symptoms commonly associated with neuropathic pain.55 Chronic neuropathic pain is “caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system” (International Association for the Study of Pain, 2011).73 Chronic neuropathic pain associated with central nervous system (CNS) injuries has been well documented in several populations including SCI47 and stroke.74 Little attention has been given, however, to neuropathic pain symptoms after a TBI.75 That said, a study76 found that pain developed within weeks to months after a moderate to severe TBI and that some of these pains had both symptoms and sensory characteristics consistent with neuropathic pain (e.g., loss of thermal sensation and evoked pain).

The TBI subjects of the present study were statistically grouped based on neuropathic pain symptom severity using their NPSI subscores. This procedure resulted in two subgroups with significantly different neuropathic pain symptom severities—one group with MNP, and one group with LNP symptoms. The average neuropathic pain severity of the MNP subgroup was comparable to a recent study in TBI77 in which 22 chronic TBI patients classified as having central neuropathic pain rated their average pain intensity in the moderate range on a visual analogue scale (4.87 ± 1.74), adding further support that the MNP subgroup in the present study experienced neuropathic pain.

The perceived severity of pain is based on a complex interaction between nociceptive signals and the modulation of such signals. The thalamus, cingulum, and insula are regions intimately involved with the perception and modulation of pain.78,79 Functional imbalance as reflected in reduced NAA levels, a marker of neuronal viability and function, in these pain networks may be an underlying mechanism of pain after TBI, similar to observations in SCI33 and heterogeneous back pain.80

In the present study, insular NAA/Cr ratios were significantly associated both with the presence of neuropathic pain symptoms and overall severity of pain. Basic research has demonstrated that the IC is intimately involved in nociceptive processes.81–83 Further, research involving the direct electrical stimulation of the IC suggests that in addition to eliciting pain, stimulation of this area also produces nonpainful sensations.84–86 Consistent with these findings, human studies show that the IC is activated by noxious stimuli,87 and that there is an association between the extent of IC activation and the intensity of a noxious stimulation, which suggests that this area is directly involved in the coding of pain intensity.88,89

Recent research also suggests that enhanced synaptic transmission, possibly from impaired inhibition in the IC, is associated with neuropathic pain behaviors in mice.90 Moreover, the insular and the cingulate cortices are part of the limbic system and therefore involved in the emotional aspects of chronic pain.91

The MNP and the LNP subgroups were compared with 45 control subjects with respect to NAA/Cr levels in the thalamus, IC, and the anterior, mid-, and posterior cingulum. An ANOVA and post hoc test revealed significantly lower insular NAA/Cr levels in the MNP subgroup compared with the LNP subgroup and the control group. The two subgroups were also compared on the PS, LI, and AD subscales of the MPI, in addition to depression, anxiety, and apathy measures to externally validate the two clusters. All of these psychological measures indicated that the MNP subgroup had significantly greater levels of PS, LI, AD, and apathy compared with the LNP subgroup. Consequently, the association with greater emotional distress may have contributed to the differences in NAA/Cr in the insula because this area has previously been identified as playing a significant role in pain-related affect.91

Recent research comparing 11 concussed athletes with controls showed average increases in the NAA/Cr ratio 3 and 15 days after injury, followed by a decrease at 30 days, and no difference in average ratios from controls at 45 days.92 Therefore, and because our TBI subjects were evaluated in the subacute phase, we controlled for this variable to account for the potential confounder of time since injury. In this analysis, greater PS, as measured with the PS subscale of the MPI,56 was significantly predicted by a combination of lower insular NAA/Cr, lower GM fractional volume (right side), female sex, and older age, whereas time since injury did not significantly influence PS. These data suggest that neuronal dysfunction and GM atrophy in the insula contribute to more severe pain with neuropathic-like symptoms.

This finding concurs with a recent study in SCI93 in which decreased GM volumes were found in the S1 cortical region representing the leg area in persons with below level neuropathic pain. These investigators also found a significant and inverse correlation between pain scores and GM volume in this region. Similarly, several studies in chronic low back pain populations have demonstrated an association between brain GM volume and both the presence and intensity of pain.14,36,94 This is consistent with brain imaging research in subjects with SCI and neuropathic pain demonstrating significant anatomical and metabolic abnormalities in different brain regions associated with both the presence of pain45 and the severity of pain.69,95

Several lines of evidence suggest that decreases in brain GM associated with a pain condition may be reversed when pain is relieved.94,96,97 In the present study, we did not follow up on pain ratings and were therefore unable to confirm this observation. Because the subjects of the present study experienced subacute pain, the observed decrease in the NAA/Cr ratio and insular GM fractional volume may represent dysfunction of inhibitory neurons and control, resulting in greater activity of excitatory neurons and a heightened sensation of pain.98

Another observation in the present study was that WM fractional volume was positively and significantly related to PS. Increased WM volume may indicate axon sprouting, dendritic branching, and remodeling, and these processes have been reported to start at approximately 10–14 days post-TBI.99,100 Other basic research has also demonstrated that axonal sprouting may occur as early as 7 days after a brain injury101 and can thus be an expected finding even in subacute TBI. For a recent review of neuronal changes after a TBI, see the article by Park and Bieder.102 Although no marker of glia was measured in the present study, previous studies in chronic SCI measuring the ratio of NAA over the glial marker, myo-inositol (Ins), or Ins alone,33,95 showed a relationship between severe neuropathic pain and thalamic Ins concentrations, which may suggest a proliferation of glia or glial activation.

In previous research,33 the severity of chronic pain in subjects with SCI was significantly associated with lower thalamic NAA. The authors proposed that the low levels of NAA were related to decreased function of inhibitory neurons in the thalamic region. Similar to these observations, thalamic levels of NAA were lower in subjects with diabetic neuropathic pain compared with pain-free individuals with diabetes. It was suggested that the reduction of thalamic NAA may contribute to the amplification of the pain signal by loss of or dysfunction in inhibitory neurons.32

Although lower thalamic concentrations of NAA have been found in persons with heterogeneous chronic pain,10 heterogeneous neuropathic pain,31 and in neuropathic pain associated with diabetes32 and SCI,33 the present study did not detect such differences. One important discrepancy between the present study and previous research is the time since injury. The pain experienced by the subjects in the present study should not be viewed as chronic because their injuries were relatively recent. Neuropathic pain after TBI is shown to develop during the first year after injury with an average onset at about 6 months.76 Although pain in the subacute period may predict the development of chronic pain, it is not known what metabolic brain changes, and in which areas, precede the development of chronic pain.

A limitation of the present study was that no information regarding pain status was collected in the control (noninjured) group. The control subjects were on average 28.7 ± 7.69 years old and were age- and sex-matched with the participants with TBI. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention103 show that the incidence of various pain conditions for the general population (ages 18–44 years) varies from 24.4% for low back pain to 5.2% for facial or jaw pain. Thus, there may be a smaller proportion of individuals in the present study's control group who experienced pain conditions. We acknowledge that this may potentially make it more difficult to uncover differences between the TBI groups and the control group.

Despite this limitation, however, we found that the NAA/Cr levels in the insula were significantly lower in the MNP subgroup (the group with the most severe pain) compared with both the LNP subgroup (the TBI group with less pain) and the control group. Moreover, both the pairwise correlations between PS and the NAA/Cr ratio and the linear regression indicated significant relationships between the two variables, and these findings support that greater pain severity is related to lower levels of insular NAA/Cr.

Conclusion

The data presented in this article demonstrate that subacute pain after TBI often has neuropathic pain characteristics, and that both the presence and severity of pain even early after TBI are reflected both in reduced insular NAA/Cr ratios and GM fractional volumes. These findings suggest that both metabolic and anatomical changes related to pain after TBI may be early indicators of the development of chronic neuropathic pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Ms. Maydelis Escalona for conducting pain assessments and Clara Morales for subject recruitment and retention. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health research grants R01NS055107 and R01EB016064, and The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), 2010; National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), 2010; National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), 2010. All data sources are maintained by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nampiaparampil D.E. (2008). Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. JAMA 300, 711–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lahz S., and Bryant R.A. (1996). Incidence of chronic pain following traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77, 889–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittenberg W., DiGiulio D.V., Perrin S., and Bass A.E. (1992). Symptoms following mild head injury: expectation as aetiology. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 200–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherer M., Davis L.C., Sander A.M., Caroselli J.S., Clark A.N., and Pastorek N.J. (2014). Prognostic importance of self-reported traits/problems/strengths and environmental barriers/facilitators for predicting participation outcomes in persons with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 1162–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson D.R., Schwartz M.L., Winocur G., and Stuss D.T. (2007). Return to productivity following traumatic brain injury: cognitive, psychological, physical, spiritual, and environmental correlates. Disabil. Rehabil. 29, 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tham S.W., Palermo T.M., Wang J., Jaffe K.M., Temkin N., Durbin D., and Rivara F.P. (2013). Persistent pain in adolescents following traumatic brain injury. J. Pain 14(, 1242–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson M.L., Elliott T.R., Berry J.W., Underhill A.T., Stavrinos D., and Fine P.R. (2013). Predictors of health-related quality-of-life following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 27, 992–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan-Singh S.J., Sawyer K., Ehde D.M., Bell K.R., Temkin N., Dikmen S., Williams R.M., and Hoffman J.M. (2014). Comorbidity of pain and depression among persons with traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 1100–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apkarian A.V., Bushnell M.C., Treede R.D., and Zubieta J.K. (2005). Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur. J. Pain 9, 463–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baliki M.N., Chialvo D.R., Geha P.Y., Levy R.M., Harden R.N., Parrish T.B., and Apkarian A.V. (2006). Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain. J. Neurosci. 26, 12165–12173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baliki M.N., Geha P.Y., Apkarian A.V., and Chialvo D.R. (2008). Beyond feeling: chronic pain hurts the brain, disrupting the default-mode network dynamics. J. Neurosci. 28, 1398–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz A.E., Yau H.J., Centeno M.V., Apkarian A.V., and Martina M. (2009). Morphological and functional reorganization of rat medial prefrontal cortex in neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 2423–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apkarian A.V., Sosa Y., Sonty S., Levy R.M., Harden R.N., Parrish T.B., and Gitelman D.R. (2004a). Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J. Neurosci. 24, 10410–10415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X.Y., Ko H.G., Chen T., Descalzi G., Koga K., Wang H., Kim S.S., Shang Y., Kwak C., Park S.W., Shim J., Lee K., Collingridge G.L., Kaang B.K., Zhuo M. (2010). Alleviating neuropathic pain hypersensitivity by inhibiting PKMzeta in the anterior cingulate cortex. Science 330, 1400–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gore M., Sadosky A., Stacey B.R., Tai K.S., and Leslie D. (2012). The burden of chronic low back pain: clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and health care costs in usual care settings. Spine 37, E668–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apkarian A.V., Sosa Y., Krauss B.R., Thomas P.S., Fredrickson B.E., Levy R.E., Harden R.N., and Chialvo D.R. (2004). Chronic pain patients are impaired on an emotional decision-making task. Pain 108, 129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dick B.D., and Rashiq S. (2007). Disruption of attention and working memory traces in individuals with chronic pain. Anesth. Analg. 104, 1223–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Hehn C.A., Baron R., and Woolf C.J. (2012). Deconstructing the neuropathic pain phenotype to reveal neural mechanisms. Neuron 73, 638–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang L., Munsaka S.M., Kraft-Terry S., and Ernst T. (2013). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to assess neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8, 576–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Govindaraju V., Young K., and Maudsley A.A. (2000). Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 13, 129–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin A.P., Liao H.J., Merugumala S.K., Prabhu S.P., Meehan W.P., 3rd, and Ross B.D. (2012). Metabolic imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 208–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Signoretti S., Marmarou A., Tavazzi B., Lazzarino G., Beaumont A., and Vagnozzi R. (2001). N-Acetylaspartate reduction as a measure of injury severity and mitochondrial dysfunction following diffuse traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 18, 977–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vagnozzi R., Signoretti S., Cristofori L., Alessandrini F., Floris R., Isgrò E., Ria A., Marziali S., Zoccatelli G., Tavazzi B., Del Bolgia F., Sorge R., Broglio S.P., McIntosh T.K., and Lazzarino G. (2010). Assessment of metabolic brain damage and recovery following mild traumatic brain injury: a multicentre, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic study in concussed patients. Brain 133, 3232–3242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Stefano N., Matthews P.M., and Arnold D.L. (1995). Reversible decreases in N-acetylaspartate after acute brain injury. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 721–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rigotti D.J., Inglese M., Kirov I.I., Gorynski E., Perry N.N., Babb J.S., Herbert J., Grossman R.I., and Gonen O. (2012). Two-year serial whole-brain N-acetyl-L-aspartate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology 78, 1383–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang L., Ernst T., Leonido-Yee M., Walot I., and Singer E. (1999). Cerebral metabolite abnormalities correlate with clinical severity of HIV-1 cognitive motor complex. Neurology 52, 100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin B.E., Katzen H.L., Maudsley A., Post J., Myerson C., Govind V., Nahab F., Scanlon B., and Mittel A. (2014). Whole-brain proton MR spectroscopic imaging in Parkinson's disease. J. Neuroimaging 24, 39–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bittner D.M., Heinze H.J., and Kaufmann J. (2013). Association of 1H-MR spectroscopy and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease: diverging behavior at three different brain regions. J. Alzheimers Dis. 36, 155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glodzik L., Sollberger M., Gass A., Gokhale A., Rusinek H., Babb J.S., Hirsch J.G., Amann M., Monsch A.U., and Gonen O. (2015) Global N-acetylaspartate in normal subjects, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease patients. J. Alzheimers Dis. 43, 939–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukui S., Matsuno M., Inubushi T., and Nosaka S. (2006). N-Acetylaspartate concentrations in the thalami of neuropathic pain patients and healthy comparison subjects measured with (1) H-MRS. Magn. Reson. Imaging 24, 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorensen L., Siddall P.J., Trenell M.I., and Yue D.K. (2008). Differences in metabolites in pain-processing brain regions in patients with diabetes and painful neuropathy. Diabetes Care 31, 980–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pattany P.M., Yezierski R.P., Widerström-Noga E.G., Bowen B.C., Martinez-Arizala A., Garcia B.R., and Quencer R.M. (2002). Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the thalamus in patients with chronic neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 23, 901–905 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gustin S.M., Wrigley P.J., Youssef A.M., McIndoe L., Wilcox S.L., Rae C.D., Edden R.A., Siddall P.J., and Henderson L.A. (2014). Thalamic activity and biochemical changes in individuals with neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain 155, 1027–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu T., Ma X.X., Xu Y.H., Xiu J.J., and Li C.F. (2008). Metabolite concentration ratios in thalami of patients with migraine and trigeminal neuralgia measured with 1H-MRS. Neurol. Res. 30, 229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt-Wilcke T., Leinisch E., Gänssbauer S., Draganski B., Bogdahn U., Altmeppen J., and May A. (2006). Affective components and intensity of pain correlate with structural differences in gray matter in chronic back pain patients. Pain 125, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Apkarian A.V., Sosa Y., Sonty S., Levy R.M., Harden R.N., Parrish T.B., and Gitelman D.R. (2004) Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. J. Neurosci. 24, 10410–10415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.As-Sanie S., Harris R.E., Napadow V., Kim J., Neshewat G., Kairys A., Williams D., Clauw D.J., and Schmidt-Wilcke T. (2012). Changes in regional gray matter volume in women with chronic pelvic pain: a voxel-based morphometry study. Pain 153,1006–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baliki M.N., Schnitzer T.J., Bauer W.R., and Apkarian A.V. (2011). Brain morphological signatures for chronic pain. PLoS One 6, e26010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis K.D., Pope G., Chen J., Kwan C.L., Crawley A.P., and Diamant N.E. (2008). Cortical thinning in IBS: implications for homeostatic, attention, and pain processing. Neurology 70, 153–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.May A. (2008). Chronic pain may change the structure of the brain. Pain 137, 7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seminowicz D.A., Labus J.S., Bueller J.A., Tillisch K., Naliboff B.D., Bushnell M.C., and Mayer E.A. (2010). Regional gray matter density changes in brains of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 139, 48–57.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Younger J.W., Shen Y.F., Goddard G., and Mackey S.C. (2010). Chronic myofascial temporomandibular pain is associated with neural abnormalities in the trigeminal and limbic systems. Pain 149, 222–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geha P.Y., Baliki M.N., Harden R.N., Bauer W.R., Parrish T.B., and Apkarian A.V. (2008). The brain in chronic CRPS pain: abnormal gray-white matter interactions in emotional and autonomic regions. Neuron 60, 570–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustin S.M., Wrigley P.J., Siddall P.J., and Henderson L.A. (2010). Brain anatomy changes associated with persistent neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1409–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lutz J., Jäger L., de Quervain D., Krauseneck T., Padberg F., Wichnalek M., Beyer A., Stahl R., Zirngibl B., Morhard D., Reiser M., and Schelling G. (2008). White and gray matter abnormalities in the brain of patients with fibromyalgia: a diffusion-tensor and volumetric imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 3960–3969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siddall P.J., McClelland J.M., Rutkowski S.B., and Cousins M.J. (2003). A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 103, 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maudsley A.A., Darkazanli A., Alger J.R., Hall L.O., Schuff N., Studholme C., Yu Y., Ebel A., Frew A., Goldgof D., Gu Y., Pagare R., Rousseau F., Sivasankaran K., Soher B.J., Weber P., Young K., and Zhu X. (2006). Comprehensive processing, display and analysis for in vivo MR spectroscopic imaging. NMR Biomed 19, 492–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins D.L., Zijdenbos A.P., Kollokian V., Sled J.G., Kabani N.J., Holmes C.J., and Evans A.C. (1998). Design and construction of a realistic digital brain phantom. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 17, 463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maudsley A.A., Domenig C., Govind V., Darkazanli A., Studholme C., Arheart K., and Bloomer C. (2009). Mapping of brain metabolite distributions by volumetric proton MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 548–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y., Brady M., and Smith S. (2001). Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 20, 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tzourio-Mazoyer N., Landeau B., Papathanassiou D., Crivello F., Etard O., Delcroix N., Mazoyer B., and Joliot M. (2002). Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15, 273–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y., and Li S.J. (1998). Differentiation of metabolic concentrations between gray matter and white matter of human brain by in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 39, 28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Folstein M.F., and Folstein S.E. (2010). Mini-Mental State Examination, 2nd ed. (MMSE-2). Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouhassira D., Attal N., Fermanian J., Alchaar H., Gautron M., Masquelier E., Rostaing S., Lanteri-Minet M., Collin E., Grisart J., and Boureau F. (2004). Development and validation of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory. Pain 108, 248–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kerns R.D., Turk D.C., and Rudy T.E. (1985). The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI). Pain 23, 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turk D.C., Dworkin R.H., Allen R.R., Bellamy N., Brandenburg N., Carr D.B., Cleeland C., Dionne R., Farrar J.T., Galer B.S., Hewitt D.J., Jadad A.R., Katz N.P., Kramer L.D., Manning D.C., McCormick C.G., McDermott M.P., McGrath P., Quessy S., Rappaport B.A., Robinson J.P., Royal M.A., Simon L., Stauffer J.W., Stein W., Tollett J., and Witter J. (2003). Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 106, 337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Ball R., and Ranieri W. (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories −IA and −II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 67, 588–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steer R.A., Brown G.K., Beck A.T., and Sanderson W.C. (2001). Mean Beck Depression Inventory-II scores by severity of major depressive disorder. Psychol. Rep. 88, 1075–1076. PMID: 11597055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haanpää M., Attal N., Backonja M., Baron R., Bennett M., Bouhassira D., Cruccu G., Hansson P., Haythornthwaite J.A., Iannetti G.D., Jensen T.S., Kauppila T., Nurmikko T.J., Rice A.S., Rowbotham M., Serra J., Sommer C., Smith B.H., and Treede R.D. (2011) NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain 152, 14–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beck A.T., Steer R.A., and Garbin M.G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 8, 77–100 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beck A.T., Epstein N., Brown G., and Steer R.A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56, 893–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kashani J.H., Suarez L., Jones M.R., and Reid J.C. (1999). Perceived family characteristic differences between depressed and anxious children and adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 52, 269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fydrich T., Dowdall D., and Chambless D.L. (1992). Reliability and validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. J. Anxiety Disord. 6, 55–61 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lindsay W.R., and Skene D.D. (2007). The Beck Depression Inventory II and the Beck Anxiety Inventory in people with intellectual disabilities: factor analyses and group data. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 20, 401–408 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beck A.T., and Steer R.A. (1990). Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Corporation. San Antonio, TX, USA [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marin R.S. (1996). Apathy: concept, syndrome, neural mechanisms, and treatment. Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 1, 304–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clarke D.E., Van Reekum R., Patel J., Simard M., Gomez E., and Streiner D.L. (2007). An appraisal of the psychometric properties of the Clinician version of the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES-C). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 16, 97–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Widerström-Noga E., Pattany P.M., Cruz-Almeida Y., Felix E.R., Perez S., Cardenas D.D., and Martinez-Arizala A. (2013). Metabolite concentrations in the anterior cingulated cortex predict high neuropathic pain impact after spinal cord injury. Pain 154, 204–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schwarz G.E. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 6, 461–464 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lavigne G., Khoury S., Chauny J.M., and Desautels A. (2015). Pain and sleep in post-concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. Pain 156, Suppl 1, S75–S85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hartvigsen J., Boyle E., Cassidy J.D., and Carroll L.J. (2014). Mild traumatic brain injury after motor vehicle collisions: what are the symptoms and who treats them? A population-based 1-year inception cohort study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, Suppl 3, S286–S294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jensen T.S., Baron R., Haanpää M., Kalso E., Loeser J.D., Rice A.S., and Treede R.D. (2011). A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain 12, 2204–22055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klit H., Finnerup N.B., and Jensen T.S. (2009). Central post-stroke pain: clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management. Lancet Neurol. 8, 857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tenovuo O. (2007). Central pain after brain trauma—a neglected problem in neglected victims. Pain 131, 241–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ofek H., and Defrin R. (2007). The characteristics of chronic central pain after traumatic brain injury. Pain 131, 330–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim J.H., Ahn S.H., Cho Y.W., Kim S.H., and Jang S.H. (2015). The relation between injury of the spinothalamocortical tract and central pain in chronic patients with mild traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 30, E40–E46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Basbaum A.I., and Fields H.L. (1978). Endogenous pain control mechanisms: review and hypothesis. Ann. Neurol. 4, 45–4–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Apkarian A.V., Baliki M.N., and Geha P.Y. (2009). Towards a theory of chronic pain. Prog. Neurobiol. 87, 81–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grachev I.D., Fredrickson B.E., and Apkarian A.V. (2000). Abnormal brain chemistry in chronic back pain: an in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Pain 89, 7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brooks J.C., Zambreanu L., Godinez A., Craig A.D., and Tracey I. (2005) Somatotopic organisation of the human insula to painful heat studied with high resolution functional imaging. Neuroimage 27, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burkey A.R., Carstens E., and Jasmin L. (1999) Dopamine reuptake inhibition in the rostral agranular insular cortex produces antinociception. J. Neurosci. 19, 4169–4179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Starr C.J., Sawaki L., Wittenberg G.F., Burdette J.H., Oshiro Y., Quevedo A.S., and Coghill R.C. (2009) Roles of the insular cortex in the modulation of pain: insights from brain lesions. J. Neurosci. 29, 2684–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mazzola L., Isnard J., Peyron R., Guénot M., and Mauguière F. (2009) Somatotopic organization of pain responses to direct electrical stimulation of the human insular cortex. Pain 146, 99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mazzola L., Isnard J., Peyron R., and Mauguière F. (2012) Stimulation of the human cortex and the experience of pain: Wilder Penfield's observations revisited. Brain 135, 631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ostrowsky K., Magnin M., Ryvlin P., Isnard J., Guenot M., and Mauguière F. (2002). Representation of pain and somatic sensation in the human insula: a study of responses to direct electrical cortical stimulation. Cereb. Cortex 12, 376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Henderson L.A., Gandevia S.C., and Macefield V.G. (2008) Gender differences in brain activity evoked by muscle and cutaneous pain: a retrospective study of single-trial fMRI data. Neuroimage 39, 1867–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Derbyshire S.W., Jones A.K., Gyulai F., Clark S., Townsend D., and Firestone L.L. (1997). Pain processing during three levels of noxious stimulation produces differential patterns of central activity. Pain 73, 431–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baliki M.N., Geha P.Y., and Apkarian A.V. (2009) Parsing pain perception between nociceptive representation and magnitude estimation. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 875–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qiu S., Zhang M., Liu Y., Guo Y., Zhao H., Song Q., Zhao M., Huganir R.L., Luo J., Xu H., and Zhuo M.J. (2014). GluA1 phosphorylation contributes to postsynaptic amplification of neuropathic pain in the insular cortex. J. Neurosci. 34, 13505–13515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grachev I.D., Fredrickson B.E., and Apkarian A.V. (2002). Brain chemistry reflects dual states of pain and anxiety in chronic low back pain. J. Neural. Transm. 109, 1309–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vagnozzi R., Signoretti S., Floris R., Marziali S., Manara M., Amorini A.M., Belli A., Di Pietro V., D'urso S., Pastore F.S., Lazzarino G., and Tavazzi B. (2013). Decrease in N-acetylaspartate following concussion may be coupled to decrease in creatine. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 28, 284–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mole T.B., MacIver K., Sluming V., Ridgway G.R., and Nurmikko T.J. (2014). Specific brain morphometric changes in spinal cord injury with and without neuropathic pain. Neuroimage Clin. 5, 28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Seminowicz D.A., Wideman T.H., Naso L., Hatami-Khoroushahi Z., Fallatah S., Ware M.A., Jarzem P., Bushnell M.C., Shir Y., Ouellet J.A., and Stone L.S. (2011). Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J. Neurosci. 31, 7540–7550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Widerström-Noga E., Cruz-Almeida Y., Felix E.R., and Pattany P.M. (2015). Somatosensory phenotype is associated with thalamic metabolites and pain intensity after spinal cord injury. Pain 156, 166–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Obermann M., Nebel K., Schumann C., Holle D., Gizewski E.R., Maschke M., Goadsby P.J., Diener H.C., and Katsarava Z. (2009). Gray matter changes related to chronic posttraumatic headache. Neurology 73, 978–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rodriguez-Raecke R., Niemeier A., Ihle K., Ruether W., and May A. (2009). Brain gray matter decrease in chronic pain is the consequence and not the cause of pain. J. Neurosci. 29, 13746–13750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Roberts M.H., and Rees H. (1991). Denervation supersensitivity in the central nervous system: possible relation to central pain syndromes, in: Pain and Central Nervous System Disease. Casey KL. (ed). Raven Press: New York, NY, pps. 219–321 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scheff S.W., Price D.A., Hicks R.R., Baldwin S.A., Robinson S., and Brackney C. (2005). Synaptogenesis in the hippocampal CA1 field following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 22, 719–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Semchenko V.V., Bogolepov N.N., Stepanov S.S., Maksimishin S.V., and Khizhnyak A.S. (2006). Synaptic plasticity of the neocortex of white rats with diffuse-focal brain injuries. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 36, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Harris N.G., Mironova Y.A., Hovda D.A., and Sutton R.L. (2010). Pericontusion axon sprouting is spatially and temporally consistent with a growth-permissive environment after traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 69, 139–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Park K., and Biederer T. (2013) Neuronal adhesion and synapse organization in recovery after brain injury. Future Neurol. 8, 555–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pleis J.R., Ward B.W., and Lucas J.W. (2010). Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health Stat. 10, 1–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]