Abstract

A combination of nitazoxanide (NTZ), peginterferon (PegIFN), and ribavirin (RBV) may result in higher sustained virologic response (SVR) rates in hepatitis C virus (HCV) monoinfected patients. This study evaluated the effect of NTZ on interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) expression in vitro and in vivo among HIV/HCV genotype-1 (GT-1) treatment-naive patients. The ability of NTZ to enhance host response to interferon (IFN) signaling using the HCV cell culture system was initially evaluated. Second, ISG expression in 53 patients with treatment outcomes [21 SVR and 32 nonresponders (NR)] in the ACTG A5269 trial, a phase-II study (4-week lead in of NTZ 500 mg daily followed by 48 weeks of NTZ, PegIFN, and weight-based RBV), was assessed. The relative expression of 48 ISGs in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was measured at baseline, week 4, and week 8 of treatment in a blinded manner. In vitro NTZ produced a direct and additive antiviral effect with IFN-alfa, with pretreatment of NTZ resulting in maximal HCV suppression. NTZ augmented IFN-mediated ISG induction in PBMCs from relapsers and SVRs (p < 0.05), but not NR. In ACTG A5269, baseline expression of most ISGs was similar between NR and SVR. NTZ minimally induced 17 genes in NR and 13 genes in SVR after 4 weeks of therapy. However, after initiation of PegIFN and RBV, ISG induction was predominantly observed in the SVR group and not NR group. NTZ treatment facilitates IFN-induced suppression of HCV replication. Inability to achieve SVR with IFN-based therapy in this clinical trial is associated with diminished ISG response to therapy that is refractory to NTZ.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem with over 180 million people infected worldwide,1 and due to shared routes of transmission, approximately one-third of all human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients are coinfected with HCV in the United States.2 While the successful implementation of antiretroviral therapy has dramatically decreased the number of AIDS-related opportunistic infections, morbidity and mortality rates related to HCV-related liver disease have increased in this group.3–5 In comparison to HCV monoinfected patients, HIV/HCV coinfected patients have an accelerated progression of liver disease and only attain modest cure rates with interferon (IFN)-based therapies.2,3 Along with significant associated toxicities, the standard treatment with IFN-based treatment yields high rates of relapse among HIV/HCV coinfected genotype-1 patients. This warrants the development of novel therapeutic regimens to improve sustained virologic response (SVR) in this population.

An adjunctive well-tolerated oral agent that had shown promising results in HCV monoinfected participants was nitazoxanide (NTZ). NTZ (2-acetyloxy-N-(5-nitro-2-thiazolyl) benzamide; Alinia), which is licensed in the United States for the treatment of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia in immunocompetent adults and children, has in vitro and clinical activity against a broad range of microorganisms, including protozoa, helminthes, bacteria, and viruses.6,7 The initial reports on HCV antiviral activity were facilitated by studies for the treatment of infectious diarrhea in Egypt, in which activity against HCV genotype 4 was coincidentally noted and studied.8,9 Other studies showed that the addition of NTZ to peginterferon (PegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) increased SVR rates from 50% to 80% in genotype-4 HCV monoinfected Egyptian patients while reporting SVR proportions of 44% versus 32% with PegIFN/RBV alone in genotype-1 (GT-1) HCV treatment-naive subjects.9,10 In HIV/HCV coinfected patients, the ACTG A5269 trial aimed to explore the efficacy of NTZ in HIV/HCV coinfected persons due to its suggested efficacy in HCV monoinfected patients, its minimal drug–drug interactions with antiretrovirals, and its known safety and tolerability in HIV-1-infected patients. This recent study showed a significant improvement in early virologic response (at least 2 log10 drop in HCV RNA from baseline) in patients treated with NTZ, however, SVR rates were similar to historic controls.11

Previously, we have shown that high baseline expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) and lack of induction of ISGs with treatment is a strong negative predictor of achieving SVR among HIV/HCV coinfected subjects.12 In this study, we performed an in vitro experimental study to determine the optimal efficacy of NTZ with IFN-alfa against HCV using a continuous infectious system. Furthermore, we evaluated the effect of NTZ on ISG expression in HIV/HCV coinfected, genotype-1 treatment-naive patients treated in the ACTG A5269 study, which used combination therapy of NTZ with PegIFN and RBV to treat HIV/HCV coinfected subjects.

Materials and Methods

Part 1: in vitro study

Study subjects

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from HIV- and HCV-negative healthy volunteers (n = 10) and HIV/HCV coinfected patients (n = 30) who were previously treated for HCV under IRB approved protocols by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). All HIV/HCV coinfected patients were treated with either Pegylated IFN-alfa 2a or 2b with weight-based RBV. Treatment responses were defined as (1) SVR (no detectable HCV RNA 24 weeks after study treatment), (2) relapser (no detectable HCV RNA at the end treatment, but rebound of detectable virus after stopping therapy), and (3) nonresponder (NR) (detectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment).

Isolation of PBMCs and culture conditions

PBMCs were isolated after leukapheresis or from heparinized peripheral blood obtained by venipuncture by Ficoll Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare). Isolated PBMCs were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Corporation, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2% glutamine and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 containing incubator for 24 h in the presence or absence of serial concentrations of IFN-alfa or NTZ (Romark Laboratories, Inc.). Synergy between PegIFN and NTZ was assessed by comparing the effect of NTZ added simultaneously with PegIFN or 72 h post-PegIFN exposure.

Cell line and culture conditions

The Huh7.5 human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line was provided by Apath LLC. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen Corporation, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FCS and 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 containing incubator.

HCV infectious clone

The infectious plasmid clone for the HCV J6/JFH1 infectious cell culture system was provided by Apath LLC. Transfection and subsequent infection of Huh 7.5 cells using this plasmid were performed as described elsewhere.13

HCV RNA quantitation

HCV RNA was determined using the Roche TaqMan HCV, v1.0 (Roche Molecular Systems), with LLQ of 43 IU/ml. Viral RNA was extracted using a viral RNA extraction Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc.). HCV copy numbers were determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Results were analyzed using the comparative Ct method for the relative quantitation of gene expression.

Cell viability assay

Assessment of cytotoxicity in the presence or absence of NTZ and/or IFN-alfa was performed using the Calcein assay kit (Biotium, Inc.). To evaluate the cytotoxicity of NTZ on cells, NTZ was added to the HCV continuous culture system at various concentrations and evaluated at 48 h.

Quantitative PCR for ISGs

Validation of DNA microarray data was performed using a multiplex qPCR assay (Applied Biosystems) capable of detecting the expression of 20 ISGs and 3 housekeeping genes as previously described.12 PBMCs in medium alone were used as a control to calculate the baseline expression of ISGs.

rs12979860 SNP genotyping

Genotyping of the ACTG A5269 and NTZ cohorts was performed by the Duke Institute for Human Genome Variation. Genotyping was conducted in a blinded manner on DNA specimens collected from each individual, using the 5′ nuclease assay with allele-specific TaqMan probes (ABI TaqMan allelic discrimination kit and the ABI7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems)). Genotyping calls were manually inspected and verified before release.

Part 2: ACTG A5269 study

Study design

ACTG A5269 trial was a single arm, phase 2 pilot study to evaluate the efficacy of NTZ added to standard of care therapy [peginterferon-alfa-2a (PegIFN) and RBV] in HIV/HCV coinfected, genotype-1, HCV treatment-naive patients. Subjects received NTZ 500 mg twice a day for 4 weeks, then the following regimen for 48 weeks: PegIFN 180 mcg subcutaneously once weekly, and weight-based RBV [≥75 kg (1,200 mg/day) or <75 kg (1,000 mg/day)]. Study criteria and details have been previously described.11 The present analysis compares 21 SVR (no detectable HCV RNA 24 weeks after study treatment) and 32 NR (detectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment).

Quantitative PCR for ISGs

Custom multiplex qPCR assay (Applied Biosystems) was used to measure expression of 48 ISGs (44 ISGs and 4 endogenous controls: 18S, GAPDH, GUSB, HPRT1) from PBMCs at baseline, week 4 (day 0 of PegIFN/RBV) and week 8 (week 4 of triple therapy).

Two-stage analysis

Stage 1: The analysis at the first stage was on samples at weeks 0 (baseline), 4, and 8 from 10 SVRs and 10 non-SVRs randomly selected from ACTG A5269. The results of the statistical tests from this stage were used to identify a subset of genes for the second stage of assays on the remaining ACTG A5269 subjects. The criterion was set at p-values <0.20 from two-sided exact Wilcoxon rank-sum tests that compared expressions from SVRs and non-SVRs. The testing laboratory was blinded to the SVR status and remained so for the remaining assays. There were 44 ISGs tested in Stage 1, plus the housekeeping genes HPRT1, GUSB, GAPDH, and 18S.

Stage 2: Based on the first stage analysis, 26 genes were selected. Twenty-two genes were selected from the baseline gene expression analysis, and an additional 4 genes from the analysis on changes in gene expression from baseline at week 4. The genes tested in the second stage were the 26 genes identified from the first stage, plus two genes (IFI27 and IFIT1) that were determined as significant genes from previous in vitro work on NTZ, and 4 housekeeping genes: 18s, GAPDH, HPRT1, and GUSB. Assays for the second stage were performed on the subjects who were not part of the first stage analysis.

Statistical methods

Part 1 (in vitro): Nonparametric tests were used for comparisons between groups.

Part 2 (ACTG A5269): The analyses were conducted using the combined data on the 28 selected genes from the two stages. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for comparisons between groups using exact methods and stratified rank-sum tests for comparisons adjusting for a covariate. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (1995) was applied to account for multiple tests on 28 ISGs, with a false discovery rate at 10% for each study objective comparison. As an exploratory analysis, overall control of false positivity is set loosely at 10% so that promising genes are not missed.14

No additional adjustments were made to control for false positivity in analyzing multiple study endpoints (e.g., baseline, fold changes at weeks 4 and 8) and to address multiple study objectives. The analysis combined data from both stages without accounting for the two-stage approach. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Part 1: in vitro study

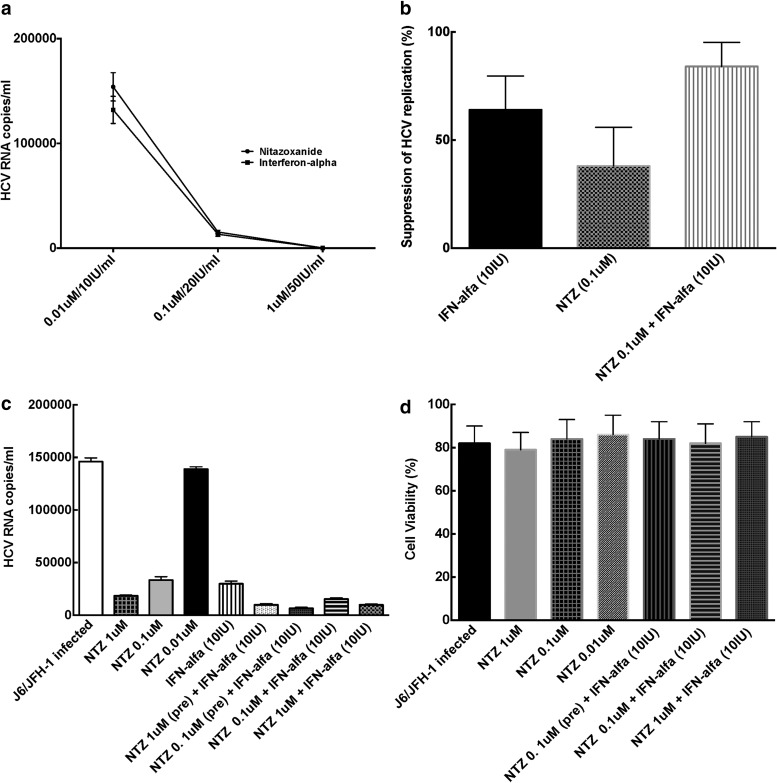

NTZ exhibits dose-dependent suppression of HCV replication in vitro

NTZ demonstrated direct suppression of HCV replication in Huh7.5 cells in a dose-dependent manner (p = 0.002, compared to untreated cells) (Fig 1a). Escalating doses of NTZ were used from a range of 0.1 μM to 1 M, which showed maximal inhibition similar to doses used in other studies.15,16 These doses were used in subsequent experiments with EC 50 and EC 90 of 0.33 and 1.1 μM, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Anti-HCV Effects of NTZ in vitro. (a) Comparable dose-dependent effects of NTZ and IFN-alfa on HCV replication. J6/JFH-1 HCVcc system was utilized to evaluate the effect of NTZ or interferon-alfa on HCV replication as described under the Materials and Methods. As shown here, both NTZ and IFN-alfa exerted a profound, dose dependent, and comparable effect on HCV replication in vitro. HCV RNA levels in the untreated medium only condition were 214,532 ± 1,354 IU/ml. All experiments were repeated four different times under identical conditions. (b) NTZ exhibits additive anti-HCV effect with IFN-alfa on HCV cc system J6/JFH-1. HCVcc system was utilized to evaluate the effect of NTZ or interferon-alfa on HCV replication as described under the Materials and Methods. As shown here, both NTZ and IFN-alfa exerted a profound effect on HCV replication in vitro, while when combined together demonstrated an additive effect. HCV RNA levels in the untreated medium only condition was 100%. All experiments were repeated four different times under identical conditions. (c) NTZ augments IFN-alfa-mediated suppression of HCV replication. J6/JFH-1 HCVcc system was utilized to evaluate the effect of pretreatment of NTZ on interferon-alfa effect on HCV replication as described under the Materials and Methods. As shown here, both pretreatment of Huh 7.5 cells with NTZ augmented the effect of IFN-alfa-based suppression of HCV in Huh 7.5 cells. HCV RNA levels in the untreated medium only condition were 187,451 ± 1,987 IU/ml. All experiments were repeated four different times under identical conditions. (d) NTZ does not affect cell viability of Huh7.5 cells. J6/JFH-1 HCVcc system was utilized to evaluate the effect of NTZ or interferon-alfa on cell viability as described under the Materials and Methods. As shown here, both NTZ and IFN-alfa alone or in combination had minimal effect on cell viability. Cell viability in the untreated medium only condition was 98.5% ± 3.4%. All experiments were repeated four different times under identical conditions. HCV, hepatitis C virus; IFN, interferon; NTZ, nitazoxanide.

NTZ has additive effect with IFN-alfa in suppressing HCV replication in vitro

We also treated Huh 7.5 cells with a combination of IFN-alfa and different doses of NTZ. We found that NTZ augmented the HCV antiviral effect of IFN-alfa leading to increased viral suppression (NTZ/IFN combination p = 0.01 vs. IFN alone and p = 0.003 vs. NTZ alone) (Fig 1b).

Pre-exposure to NTZ followed by IFN-alfa results in maximal suppression of HCV replication in vitro

It has been suggested that pretreatment with NTZ might lead to changes in the intracellular environment, thereby altering the treatment effect of subsequent therapies.16 We found that pretreatment with NTZ resulted in greater in vitro HCV suppression of HCV replication when compared to combination therapy with IFN and NTZ without pretreatment in vitro (p = 0.001) (Fig 1c).

NTZ does not lead to cell apoptosis in vitro

NTZ and its active metabolite are highly bound (>99%) to plasma proteins in serum.17,18 Higher concentrations of NTZ slightly lowered cell viability; however, over 85% of cells were still viable (Fig 1d).

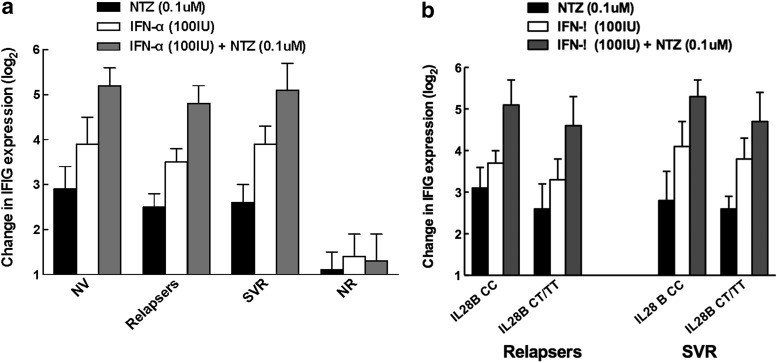

NTZ induces ISG expression in PBMCs from normal volunteers, relapsers, and SVR, but not from NR

We have previously shown that induction of ISGs after initiation of therapy is associated with good treatment response12 and sought to evaluate the induction of the ISG pathway with NTZ. PBMCs in medium alone were used as a control to calculate baseline expression of ISGs. Treatment of PBMCs with NTZ resulted in a direct induction (fold change) of ISGs in PBMCs of relapsers (p = 0.01) and sustained responders (p = 0.003), but not NR (p = 0.05) (Fig 2a). NTZ treatment also significantly augmented IFN-mediated ISG expression in PBMCs from relapsers (p = 0.002) and SVR (p = 0.001), but not NR (p = 0.3). NTZ had similar effects on induction of ISG responses in both relapsers and SVR, irrespective of IL28B haplotype (Fig 2b). The distribution of IL28B CC haplotype was 0% for NR, 40% for relapsers, and 50% for those who achieved SVR. IL28B CC haplotype has been associated with SVR and induction of ISG response.19

FIG. 2.

Augmentation of IFN-inducible genes by NTZ. (a) NTZ augments IFN-inducible gene expression in PBMCs from HIV-negative normal volunteers, HIV/HCV-coinfected relapsers and SVRs, but not nonresponders. IFN-inducible gene expression was determined using PBMC (from normal volunteers, relapsers, those with SVR, and nonresponders) treated with either NTZ alone (0.1 μM), IFN-alfa alone (100 IU/ml), or both NTZ (0.1 μM) and IFN-alfa (100 IU/ml) as described in the Materials and Methods. PBMCs in medium alone were used as a control to calculate baseline expression of interferon-stimulated genes. As shown in the figure, addition of NTZ augmented the effect of IFN-alfa-mediated induction of IFN-inducible genes in all groups of patients except nonresponders. (b) NTZ augments IFN-inducible gene expression in PBMCs from HIV/HCV-coinfected relapsers and SVRs, irrespective of IL28B haplotype. IFN-inducible gene expression was determined using PBMC (from relapsers and those with SVR who were either IL28B cc or non-CC haplotypes) treated with either NTZ alone (0.1 μM), IFN-alfa alone (100 IU/ml), or both NTZ (0.1 μM) and IFN-alfa (100 IU/ml) as described in the Materials and Methods. IL28B CC haplotypes are associated with overall better response to interferon-based HCV therapy. Hence, IL28B non-CC haplotypes are less amenable to achieve SVR using IFN-based therapy. As shown in the figure, addition of NTZ augmented the effect of IFN-alfa-mediated induction of IFN-inducible genes in all groups of patients, regardless of IL28B haplotype suggesting that NTZ may be able to overcome genetic barriers of lack of response to IFN-alfa-based therapy. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; SVR, sustained virologic response.

Part 2: ACTG A5269 study

Study population

A subset of 53 patients (21 SVR, 32 NR) with confirmed outcomes was included in the final analysis (Table 1). Patients were predominantly male (83%), median age (49), IL28B CT/TT haplotype with genotype-1a infection (72%) largely representative of the HCV epidemic in the United States. About 70% was suppressed on current antiretroviral therapy. Non-nucleoside or protease inhibitor regimens comprised 75% of these regimens.

Table 1.

ACTG A5269 Baseline Characteristics of 21 SVR and 32 NR

| Baseline characteristics, n (%) or median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Host factors | SVR (n = 21) | NR (n = 32) | Total (n = 53) |

| Median age | 46 (42.54) | 50 (44.54) | 49 (43.54) |

| Male gender | 18 (85.7) | 26 (81.3) | 44 (83.0) |

| Black race | 10 (47.6) | 18 (56.3) | 28 (52.8) |

| BMI <30 | 17 (80.9) | 23 (71.9) | 40 (75.5) |

| IL28B C/T OR T/T haplotype | 13 (61.9) | 25 (78.2) | 38 (71.7) |

| HCV-related measures | |||

| Genotype | |||

| 1a | 14 (66.7) | 24 (75.0) | 38 (71.7) |

| 1b | 6 (28.6) | 7 (21.9) | 13 (24.5) |

| Log HCV RNA | 6.29 (5.92, 6.64) | 6.63 (6.16, 7.02) | 6.41 (6.03, 6.73) |

| APRI >1.5 | 2 (9.5) | 5 (15.6) | 7 (13.2) |

| FIB-4 > 3.25 | 1 (4.8) | 7 (21.9) | 8 (15.1) |

| HIV-related measures | |||

| CD4 | 446 (357, 748) | 439.50 (306.5, 727) | 445 (323, 738) |

| Proportion HIV VL suppressed | 16 (76.2) | 21 (65.6) | 37 (69.8) |

| HIV ARV regimen | |||

| Non-nuc | 11 (52.4) | 9 (28.1) | 20 (37.7) |

| PI | 6 (28.8) | 14 (43.4) | 20 (37.7) |

| Integrase inhibitor | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Other | 2 (9.6) | 4 (12.4) | 6 (11.3) |

| No ARVs | 1 (4.8) | 5 (15.6) | 6 (11.3) |

ARV, antiretroviral; BMI, body mass index; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NR, nonresponder; SVR, sustained virologic response; VL, viral load.

ISG expression

Baseline ISG expression as a predictor of SVR or nonresponse

High baseline ISG expression has been described as a negative predictor of achieving SVR in PegIFN- and RBV-based therapy for coinfected subjects. We examined whether there was a difference between baseline ISG expression between SVR and NR in the ACTG A5269 cohort. There were no statistically significant differences detected between SVR and nonresponse groups with respect to baseline gene expression. IFIT2 was expressed higher in SVR and ranked with the lowest p-value (p = 0.12, unadjusted for multiple tests) (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid).

Induction of ISG after 4 weeks of NTZ pretreatment

One of the proposed mechanisms of action of NTZ is to induce ISG expression by enhancing protein kinase R (PKR) phosphorylation.20 In this clinical trial, all subjects received 4 weeks of pretreatment with NTZ before initiation of PegIFN and RBV. We investigated whether there was a difference in ISG induction by NTZ between the two response groups (SVR and NR). There were 17 genes upregulated in NR and 13 genes upregulated in SVR, while other genes were unchanged. Hence, NTZ treatment was able to induce ISG expression in these subjects, regardless of therapeutic outcome of combination therapy (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

ACTG A5269 Gene Expression After 4 Weeks of Nitazoxanide Pretreatment; After Week 4 Interferon, Week 8 Nitazoxanide

| Week 4 change from baseline | Week 8 change from week 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | p* | Higher in | SVR | NR | Gene | p* | Higher in | SVR | NR |

| IFI27 | 0.17 | NR | Down | Up | IFI27 | 0.334 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFI44 | 0.093 | NR | Down | Up | IFI44 | 0.065 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFIT1 | 0.595 | SVR | Up | Down | IFIT1 | 0.649 | NR | Up | Up |

| IFIT2 | 0.082 | NR | Down | Down | IFIT2 | 0.268 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFIT3 | 0.522 | NR | Up | Up | IFIT3 | 0.864 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFITM2 | 0.685 | NR | Down | Up | IFITM2 | 0.134 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFITM3 | 0.097 | NR | Up | Up | IFITM3 | 0.343 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFNA2 | 0.826 | NR | Down | Down | IFNA2 | 0.782 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IFNB1 | 0.685 | SVR | Up | Down | IFNB1 | 0.878 | SVR | Up | Down |

| IRF1 | 0.993 | SVR | Up | Up | IRF1 | 0.561 | SVR | Down | Down |

| IRF7 | 0.419 | NR | Down | Down | IRF7 | 0.546 | SVR | Up | Up |

| IRF9 | 0.893 | NR | Down | Down | IRF9 | 0.443 | SVR | Up | Up |

| ISG15 | 0.135 | NR | Down | Up | ISG15 | 0.780 | SVR | Up | Up |

| LY6E | 0.044 | NR | Down | Up | LY6E | 0.167 | SVR | Up | Up |

| MX1 | 0.249 | NR | Down | Up | MX1 | 0.249 | SVR | Up | Up |

| MX2 | 0.794 | NR | Down | — | MX2 | 0.364 | SVR | Up | Up |

| OAS1 | 0.371 | NR | Up | Up | OAS1 | 0.907 | NR | Up | Up |

| OAS2 | 0.473 | SVR | Up | Up | OAS2 | 0.465 | SVR | Up | Up |

| OASL | 0.113 | NR | Down | Up | OASL | 0.479 | SVR | Up | Up |

| PLSCR1 | 0.381 | NR | Down | Up | PLSCR1 | 0.850 | NR | Up | Up |

| RARRES3 | 0.177 | NR | Up | Up | RARRES3 | 0.555 | SVR | Up | Up |

| SP110 | 0.159 | NR | Up | Up | SP110 | 0.222 | SVR | Up | Up |

| STAT1 | 0.065 | NR | Up | Up | STAT1 | 0.274 | SVR | Up | Up |

| STAT2 | 0.822 | NR | Down | — | STAT2 | 0.698 | SVR | Up | Up |

| STAT6 | 0.893 | SVR | Up | — | STAT6 | 0.763 | SVR | Up | Up |

| TRIM14 | 0.646 | NR | Up | Up | TRIM14 | 0.409 | SVR | Up | Up |

| TRIM5 | 0.534 | SVR | Up | — | TRIM5 | 0.558 | SVR | Up | Up |

| TYK2 | 0.893 | SVR | Down | Down | TYK2 | 0.907 | SVR | Up | Up |

The comparisons of gene expression at various times after enrollment is made to the baseline gene expression. Week 4 and 8 changes: gene expression = 2(ΔCt), where ΔCt = [(target gene Ct)–(GAPDH Ct)]. Baseline, week 4 and week 8 gene expressions are the values of 2(ΔCt) at weeks 0, 4, and 8, respectively: 2(−Δ4ΔCt) >1 refers to upregulation at week 4 compared to baseline; 2(−Δ4ΔCt) <1 refers to downregulation at week 4 compared to baseline; Similar interpretation for 2(−Δ8Δ4) at week 8 compared to week 4.

None met the predetermined false discovery rate at 10% using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for multiple tests.

Exact Wilcoxon test.

—, genes for which expression did not change.

At Week 8: (week 4 IFN, week 8 NTZ)

Next, we examined whether enhancing IFN responsiveness with NTZ pretreatment would result in an induction of ISG expression. There were 27 genes upregulated at week 8 from week 4. In this regard, those who achieved SVR had an increase in most ISGs compared to those in NR (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that NTZ exhibits potent direct anti-HCV activity and is able to potentiate the anti-HCV effect of IFN-alfa in vitro. The additive effect of ISG induction, which is a surrogate marker of host response to PegIFN/RBV therapy, is not observed among NR, suggesting this group of individuals may not benefit from an IFN-sensitizing regimen. However, the addition of an agent that stimulates the IFN signaling cascade such as NTZ may be effective for IFN relapsers. In vitro studies performed in our laboratory and elsewhere suggest that NTZ has both (1) a direct suppressive effect on HCV replication and (2) a sensitizing effect on IFN gene signature and IFN-mediated suppression of HCV replication. Furthermore, NTZ pretreatment of HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects enhanced IFN signaling in PBMCs, regardless of the therapeutic outcome. However, NTZ resulted in lower induction of ISG by PegIFN and RBV in PBMCs from those who failed to achieve SVR than those who did.

These data are consistent with in vitro studies9,16 that have suggested that NTZ has both direct and synergistic suppression of HCV replication. Phosphorylated eIF2alfa (p-eIF2α) and activated PKR are important mediators in the IFN-inducible antiviral pathways. Recent studies using Huh7 cells containing HCV genotype-1 replicons or Huh7.5 cells infected with HCV genotype-2a J6/JFH virus demonstrated that intracellular concentrations of p-eIF2α and the dsRNA-activated PKR were increased with NTZ treatment.15 In addition, NTZ increased phosphorylation of PKR, which was more pronounced in the presence of HCV viral RNA. These findings suggest that NTZ likely induces PKR phosphorylation, resulting in an increased intracellular concentration of p-eIF2α, a key mediator of host defenses against viruses, and serves as a key explanation of NTZ's antiviral effects.20 The addition of IFN to cell cultures further increased NTZ-induced p-eIF2α. In vitro, NTZ promoted PKR autophosphorylation, a key step in activating PKR's kinase activity for eIF2alfa. Finally, NTZ-induced p-eIF2α was reduced in the presence of specific inhibitors of PKR autophosphorylation, a key kinase that regulates the cell innate antiviral response. NTZ might represent a new class of small molecules capable of potentiating and recapitulating important antiviral effects of IFN.17 In contrast to the available and upcoming directly acting anti-HCV agents, NTZ does not appear to induce direct antiviral resistance based on serial passage of HCV replicon-containing cell lines with increasing concentrations of NTZ and tizoxanide.21 Our data demonstrating additive effect of NTZ on HCV replication with IFN-alfa are consistent with this proposed mode of action.

Our study demonstrates the activity of NTZ in augmenting IFN response in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. Previously, we have shown that high baseline expression of ISGs and lack of induction of ISGs with treatment are strong negative predictors of achieving SVR among HIV/HCV coinfected subjects.12 In this regard, NTZ pretreatment resulted in enhanced IFN signaling in most study subjects. These data would suggest that NTZ is capable of inducing IFN signaling leading to ISG expression in HIV/HCV coinfected subjects, although the exact mechanism by which this happens is unclear. The basic assumption for the clinical trial design using a pretreatment phase of NTZ alone was to achieve sensitization of immune cells to exogenous IFN/RBV therapy similar to what we observed in vitro. However, PegIFN/RBV/NTZ therapy resulted in lower ISG induction in PBMCs from NR than that was observed in PBMCs of those who achieved SVR, suggesting a refractoriness in the IFN signaling pathway in nonresponders.

Future studies will focus on understanding the mechanisms of this refractoriness of IFN signaling observed in NR and development of modalities that may aid in its reversal. Such strategies may be vital in improving the response rates of HCV therapy in this difficult to treat patient population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ACTG A5269 members and funding: ACTG Network Leadership Grant 1U01AI068636. ACTG Statistical and Data Management Center Grant 1U01AI068634. For HCV RNA and HCV genotyping efforts performed at Dr.Victoria A. Johnson's UAB Virology Laboratory 54: James Darren Hazelwood.UAB VSL grant (NIH/NIAID 7UM1AI068636).

This research was supported in part with federal funds from the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, National Institutes of Health (AI000390).

This work was presented as a poster presentation at CROI March 2013, Boston, Massachusetts.

Disclaimer

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, or does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization that imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author Disclosure Statement

Anu Osinusi is an employee of Gilead Sciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hanafiah KM, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST: Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013;57:1333–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funk EK, Shaffer A, Shivakumar B, et al. : Interferon/ribavirin treatment for HCV is associated with the development of hypophosphatemia in HIV/hepatitis C Virus-coinfected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013;29:1190–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain MK, Skiest DJ, Cloud JW, Jain CL, Burns D, Berggren RE: Changes in mortality related to human immunodeficiency virus infection: Comparative analysis of inpatient deaths in 1995 and in 1999–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selik RM, Byers RH, Jr., Dworkin MS: Trends in diseases reported on U.S. death certificates that mentioned HIV infection, 1987–1999. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;29:378–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Sierra C, Arizcorreta A, Diaz F, et al. : Progression of chronic hepatitis C to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:491–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubreuil L, Houcke I, Mouton Y, Rossignol JF: In vitro evaluation of activities of nitazoxanide and tizoxanide against anaerobes and aerobic organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996;40:2266–2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossignol JF: Nitazoxanide in the treatment of acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related cryptosporidiosis: Results of the United States compassionate use program in 365 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamal SM, Nasser IA: Hepatitis C genotype 4: What we know and what we don't yet know. Hepatology 2008;47:1371–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossignol JF, Elfert A, El-Gohary Y, Keeffe EB: Improved virologic response in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 treated with nitazoxanide, peginterferon, and ribavirin. Gastroenterology 2009;136:856–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossignol JF, Elfert A, Keeffe EB: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C using a 4-week lead-in with nitazoxanide before peginterferon plus nitazoxanide. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44:504–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amorosa VK, Luetkemeyer A, Kang M, et al. : Addition of nitazoxanide to PEG-IFN and ribavirin to improve HCV treatment response in HIV-1 and HCV genotype 1 coinfected persons naive to HCV therapy: Results of the ACTG A5269 trial. HIV Clin Trials 2013;14:274–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottilil S, Yan MY, Reitano KN, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C infections induce distinct immunologic imprints in peripheral mononuclear cells. Hepatology 2009;50:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, et al. : Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med 2005;11:791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenfeld D: Statistical considerations for pilot studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1980;6:371–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elazar M, Liu M, McKenna SA, et al. : The anti-hepatitis C agent nitazoxanide induces phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha via protein kinase activated by double-stranded RNA activation. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1827–1835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korba BE, Montero AB, Farrar K, et al. : Nitazoxanide, tizoxanide and other thiazolides are potent inhibitors of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus replication. Antiviral Res 2008;77:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broekhuysen J, Stockis A, Lins RL, De Graeve J, Rossignol JF: Nitazoxanide: Pharmacokinetics and metabolism in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000;38:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockis A, Deroubaix X, Lins R, Jeanbaptiste B, Calderon P, Rossignol JF: Pharmacokinetics of nitazoxanide after single oral dose administration in 6 healthy volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996;34:349–351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. : Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009;461:399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elazar M LM, McKenna S, Liu P, Gehrig EA, Elfert A, et al. : Nitazoxanide is an inducer EIF2A and PKR phosphorylation. Hepatology 2008;48:1151A [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korba BE, Elazar M, Lui P, Rossignol JF, Glenn JS: Potential for hepatitis C virus resistance to nitazoxanide or tizoxanide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:4069–4071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.