Abstract

Introduction: Industrial livestock farming is a possible source of multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, including producers of extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) conferring resistance to 3rd generation cephalosporins. Limited information is currently available on the situation of ESBL producers in livestock farming outside of Western Europe. A surveillance study was conducted from January to May in 2014 in four dairy cattle farms in different areas of the Nile delta, Egypt.

Materials and Methods: In total, 266 samples were collected from 4 dairy farms including rectal swabs from clinically healthy cattle (n = 210), and environmental samples from the stalls (n = 56). After 24 h pre-enrichment in buffered peptone water, all samples were screened for 3rd generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli using Brilliance™ ESBL agar. Suspected colonies of putatively ESBL-producing E. coli were sub-cultured and subsequently genotypically and phenotypically characterized. Susceptibility testing using the VITEK-2 system was performed. All suspect isolates were genotypically analyzed using two DNA-microarray based assays: CarbDetect AS-1 and E. coli PanType AS-2 kit (ALERE). These tests allow detection of a multitude of genes and their alleles associated with resistance toward carbapenems, cephalosporins, and other frequently used antibiotics. Serotypes were determined using the E. coli SeroGenotyping AS-1 kit (ALERE).

Results: Out of 266 samples tested, 114 (42.8%) ESBL-producing E. coli were geno- and phenotypically identified. 113 of 114 phenotypically 3rd generation cephalosporin-resistant isolates harbored at least one of the ESBL resistance genes covered by the applied assays [blaCTX-M15 (n = 105), blaCTX-M9 (n = 1), blaTEM (n = 90), blaSHV (n = 1)]. Alarmingly, the carbapenemase genes blaOXA-48 (n = 5) and blaOXA-181 (n = 1) were found in isolates that also were phenotypically resistant to imipenem and meropenem. Using the array-based serogenotyping method, 66 of the 118 isolates (55%) could be genotypically assigned to O-types.

Conclusion: This study is considered to be a first report of the high prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in dairy farms in Egypt. ESBL-producing E. coli isolates with different underlying resistance mechanisms are common in investigated dairy cattle farms in Egypt. The global rise of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria is a big concern, and demands intensified surveillance.

Keywords: ESBL, carbapenemases, Escherichia coli, Egypt, dairy cattle, microarray, genotype, CRE

Introduction

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) are mainly plasmid-encoded enzymes providing resistance to 3rd generation (3G) cephalosporins. These enzymes can be produced by a variety of different bacteria, such as Enterobacteriaceae or non-fermenting bacteria (Bradford, 2001; Giamarellou, 2005; Rawat and Nair, 2010; Shaikh et al., 2015). The most frequently found ESBL-producing species is Escherichia coli which often causes urinary tract infections, pneumonia or even sepsis in humans (Abraham et al., 2012). ESBL-producing E. coli has been broadly recognized in veterinary medicine as causative agents of mastitis in dairy cattle since the 2000s (Brinas et al., 2003; Haftu et al., 2012), but only a few studies exist that investigated the prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria in livestock, showing their existence in sick and/or healthy cattle (Valentin et al., 2014; Dahms et al., 2015).

Unfortunately, there is no legislation in Egypt regulating the use of antibiotics (Dahshan et al., 2015). Antimicrobials such as tetracycline, quinolones, and beta lactams are still used in Egypt for growth promotion in animal feed and by veterinarians for the treatment and prevention of zoonotic diseases (WHO, 2013).

The CTX-M beta-lactamases, named for their greater activity against cefotaxime, are the most frequently detected ESBLs in livestock, and have been reported from different food-producing animals (Schmid et al., 2013; Brolund, 2014; Hansen et al., 2014). These animals also represent a source and/or a reservoir for ESBL-producing E. coli (Carattoli, 2008). Several studies indicate that these resistance genes are disseminated through the food chain or via direct contact between humans and animals (Schmid et al., 2013; Dahms et al., 2015). Data on ESBL-producing bacteria in food animals from Egypt are very limited. Therefore, the current study was conducted on four dairy cattle farms in different districts of Northern Egypt to assess the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in dairy cattle and their environment.

Materials and methods

Farm description and sampling

In 2014, four dairy farms, three in Gamasa (GF1, GF2, GF5), and one in Damietta (D), were investigated (Figure 1). These farms were located in Nile Delta, Egypt in two different governorates (Damietta; Latitude N. 31⋅19′, Longitude E. 31⋅81′ and Dakahlia Latitude N. 31⋅25′, Longitude E. 31⋅32′). The herd size ranged from 400, 600, 650, and 800 in GF1, GF2, GF5, and D, respectively. The cattle enrolled in this study were between 2 and 10 years old. Half of the farms housed dairy cattle in free-stall barns and half of them in tie-stall barns. In total, 266 samples were collected from these farms. This included rectal swabs and milk samples from apparently healthy dairy cattle (n = 210), and environmental swab samples from water trough, feed and bedding (n = 56).

Figure 1.

Map of Nile Delta, Egypt with all locations of the dairy cattle farms from which the samples were collected (GF-Gamasa, D-Damietta).

Bacterial strains, isolation, identification, and genomic DNA extraction

All collected samples were enriched in buffered peptone water and cultivated on Brilliance™ ESBL agar (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) for preliminary analysis for ESBL-producing E. coli. For further investigations, all suspected E. coli that grew on the selective medium were cultivated on tryptone yeast agar (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany). Presumptive characteristic E. coli isolates were identified by Gram staining and motility, and confirmed using a panel of biochemical tests (Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) agar, catalase, oxidase, H2S production and sugar fermentation) and API 20 E systems (bioMérieux, France; ISO, 2001). All confirmed isolates were subsequently re-tested using an automated microdilution technique (VITEK-2, bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany) that covered the following antibiotics: imipenem, meropenem, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefuroxime-axetil, cefuroxime, piperacillin/tazobactam, ampicillin/sulbactam, ampicillin, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, tetracycline, tigecycline, co-trimoxazol, and fosfomycin (VITEK-2 test card: AST-N289). Susceptibility tests for chloramphenicol, kanamycin, streptomycin, erythromycin and colistin were not performed in this study.

Genomic DNA from clonal isolates was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. When necessary, DNA was concentrated to at least 100 ng/μl using a SpeedVac centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at room temperature with 1400 rpm and for 30 min. Five microliters of recovered genomic DNA were used directly for biotin-labeling and subsequent hybridization.

GenoSeroTyping and antimicrobial resistance genotype

For all ESBL-producing E. coli, the serotype was determined using the E. coli SeroGenoTyping AS-1 kit. The antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genotype was detected by the CarbDetect AS-1 kit and all other resistance genes were detected by the E. coli PanType AS-2 kit (Alere Technologies GmbH, Jena, Germany). The data were automatically summarized by the “result collector,” a software tool provided by Alere Technologies. An antibiotic resistance genotype was defined as a group of genes which have been described to confer resistance to a family of antibiotics (e.g., the genotype “blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM” confers resistance to 3G cephalosporins) (Table 2).

Multiplex labeling, hybridization, and data analysis

Extracted DNA was labeled by primer extension amplification using E. coli SeroGenoTyping AS-1, CarbDetect AS-1 or E. coli PanType AS-2 kits according to manufacturer's instructions. The procedure for multiplex labeling, hybridization and data analysis was described in detail by Braun et al. (2014). Briefly, internal labeling of the synthesized single stranded DNA resulted from the primer elongation of previously hybridized primers to the target genomic DNA, by using dUTP linked biotin as dideoxynucleotide triphosphate to be incorporated during synthesis. This procedure allowed site-specific internal labeling of the corresponding target region. The PCR protocol included 5 min of initial denaturation at 96⋅C, followed by 50 cycles with 20 s of annealing at 50⋅C, 40 s of elongation at 72⋅C, and 60 s of denaturation at 96⋅C (used device: Eppendorf Mastercycler gradient, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). This reaction resulted in a multitude of specific linearly amplified, single-stranded, biotin-labeled DNA molecules for subsequent hybridization and detection using the DNA microarrays.

For hybridization procedures, the CarbDetect AS-1 and the E. coli PanType AS-2 kit were used according to manufacturer's instructions. CarbDetect ArrayStrips were placed in a thermomixer with an Alere ArrayStrip adapter (Quantifoil Instruments, Jena, Germany) and subsequently washed with 200 μl of deionized water at 50⋅C with 550 rpm for 5 min and with 100 μl hybridization buffer C1 at 50⋅C with 550 rpm for 5 min. Liquids were always completely removed using a soft plastic pipette (e.g., BRANDT, #612-2856) to avoid any scratching of the chip surface. In a separate tube, 10 μl of previously labeled, single-stranded DNA was dissolved in 90 μl hybridization buffer C1. The hybridization was carried out at 50⋅C and 550 rpm for 1 h. After hybridization, the ArrayStrips were washed twice using 200 μl washing buffer C2 at 45⋅C for 10 min, shaking at 550 rpm. Peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate C3 was diluted 1:100 in buffer C4. A total of 100 μl of this mixture was added to each well of the ArrayStrip and subsequently incubated at 30⋅C and 550 rpm for 10 min. Thereafter, two washing steps with 200 μl C5 washing buffer were carried out at 550 rpm at 30⋅C for 5 min. The visualization was achieved by adding 100 μl of staining substrate D1 to the ArrayStrips, and signals were detected using the ArrayMate device (Alere Technologies GmbH). Finally, an automatically generated HTML-report was provided giving information on the presence or absence of antimicrobial resistance genes and the affiliation to one of the more common species.

Ethic statement

An Ethic Statement is not necessary. The isolates were obtained by noninvasive rectal swabs and no animal experiments were carried out for this study.

Results

Antimicrobial resistance genotype and phenotype

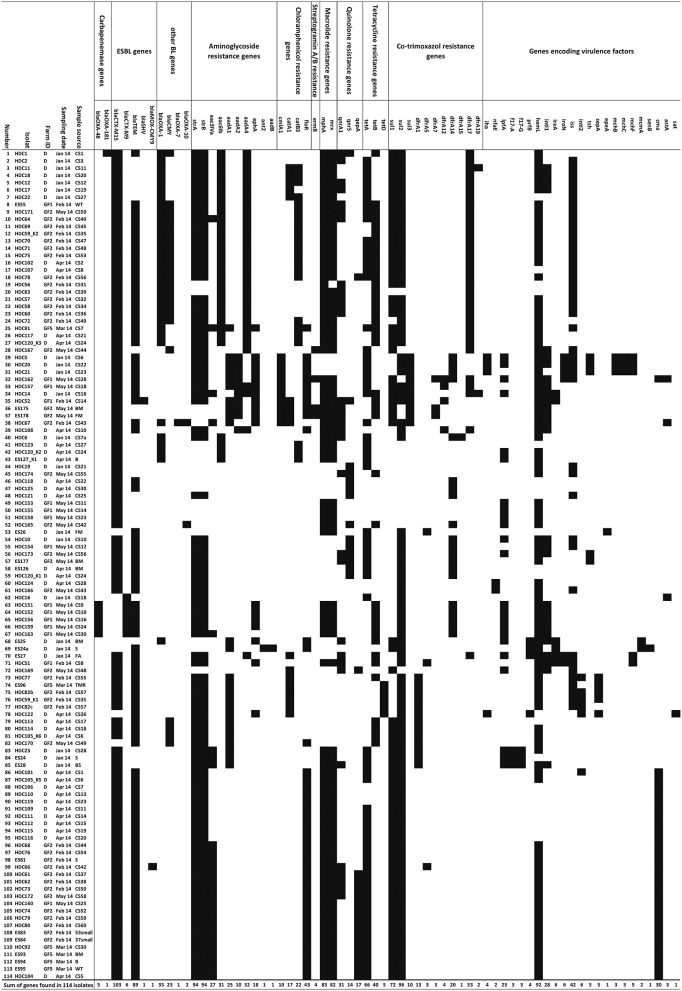

Rectal swabs samples (n = 210) yielded 98 (46.6%) cultures and environmental samples (n = 56) yielded 16 (28.6%) cultures of putatively ESBL-producing E. coli. All 114 isolates were Gram-negative, motile, catalase positive, oxidase negative and indole-producing bacteria. Additionally, all isolates caused a decrease of pH and a color change of the TSI agar indicator and gas formation in the bottom of the test tube, and were therefore assigned as E. coli. In total, 113 (99.1%) phenotypically 3G cephalosporin-resistant isolates harbored at least one of the ESBL genes covered by the microarray (blaCTX-M15, blaCTX-M9, blaTEM, blaSHV; Figure 2). The carbapenemase gene blaOXA-48 was detected in five isolates (3.4%) and the carbapenemase gene blaOXA-181 (0.8%) was detected in one isolate (Table 1, Figure 2). These isolates showed a phenotypic resistance to imipenem and meropenem (Table 2). The total number of detected resistance genes is listed in Table 1 and an overview to each isolate is given in Figure 2. The ESBL gene blaCTX-M1/15 was found in 103 isolates whereas blaCTX-M9 was only found in 9 isolates. Consensus sequences for blaTEM and blaSHV were found in 89 and 1 isolate, respectively. For all detected beta-lactamase genotypes, the phenotype was analyzed using the VITEK-2 instrument. The results are shown in Table 2. The concordance for the carbapenem resistance and ESBL genotype was 100%. In one phenotypic ESBL positive isolate, only the narrow spectrum beta-lactamase (NSBL) gene blaOXA-1 was found. Due to this unexpected phenotype the concordance for the NSBL genotype was only 60%.

Figure 2.

Overview of antimicrobial resistance pattern. Antimicrobial resistant genes of all E. coli isolates obtained from swab samples (healthy dairy cattle and/or environment). Also given are the farm IDs, sample sources and sampling dates. (Abbreviations: CS, rectal swab; WT, water trough; BM, bulk milk; S, soil; FM, feed mixer; FA, feed animal; BS, boot swab; B, bedding; TMR, total mixed ration).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial resistance genes and their frequency in E. coli isolates detected by microarray.

| Gene family | Genes | Accession No. | Description | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenemase | blaOXA-48 | AY236073.2 | Carbapenemase, class D carbapenem hydrolyzing beta-lactamase | 5 |

| blaOXA-181 | JN205800.1 | Carbapenemase, class D carbapenem hydrolyzing beta-lactamase | 1 | |

| ESBL (extended spectrum beta- lactamase) | blaCTX-M1/15 | X92506.1 | Class A extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase | 103 |

| blaCTX-M9 | AF174129.3 | Class A extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase | 6 | |

| blaTEM | Consensus | Class A beta-lactamase | 89 | |

| blaSHV | Consensus | Class A beta-lactamase | 1 | |

| blaMOX-CMY9 | AF381617.1 | Class C beta-lactamase | 1 | |

| NSBL (narrow spectrum beta-lactamase) | blaOXA-1 | AY458016.1 | Class D beta-lactamase | 33 |

| blaOXA-7 | AY866525.1 | Class D beta-lactamase | 1 | |

| blaOXA-10 | J03427.1 | Class D beta-lactamase | 2 | |

| blaCMY | AB212086.1 | Class C beta-lactamase | 23 | |

| Aminoglycosides | strA | EF090911.1 | Aminoglycoside-3″-phosphotransferase (locus A) | 94 |

| strB | EF090911.1 | Aminoglycoside-6″-phosphotransferase | 94 | |

| aadA4 | Z50802.3 | Aminoglycoside adenyltransferase | 32 | |

| aac(6′)-Ib | AM283490.1 | Aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase | 31 | |

| aac(3′)-IVa | EU784152.1 | Aminoglycoside 3′-N-acetyltransferase | 27 | |

| aadA1 | EU704128.1 | Aminoglycoside adenyltransferase | 25 | |

| aphA | AY260546.3 | Aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferase | 18 | |

| aadA2 | EU704128.1 | Aminoglycoside adenyltransferase | 10 | |

| aadB | L06418.4 | Aminoglycoside 2″-O-nucleotidyltransferase | 1 | |

| Chloramphenicol | floR | AF252855.1 | Florfenicol export protein | 43 |

| catB3 | AJ009818.1 | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (group B) | 22 | |

| catA1 | V00622.1 | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (group A) | 17 | |

| cmlA1 | EF113389.1 | Chloramphenicol transporter | 10 | |

| Streptogramin A/B | ermB | AB089505.1 | rRNA adenine N-6-methyltransferase | 4 |

| Macrolides | mphA | AB038042.1 | Macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase I | 83 |

| Mrx | AB038042.1 | Unknown (downstream to mphA) | 82 | |

| Fluoroquinolones | qnrA | AY931018.1 | Quinolone or fluoroquinolone resistance protein | 31 |

| qepA | AM886293.1 | Fluoroquinolone efflux pump | 17 | |

| qnrS | AM234722.1 | Quinolone or fluoroquinolone resistance protein | 14 | |

| Tetracycline | tetA | CP000971.1 | Tetracycline resistance protein A, class A | 66 |

| tetB | V00611.1 | Tetracycline resistance protein A, class B | 40 | |

| tetD | X65876.1 | Tetracycline resistance protein A, class D | 5 | |

| Co-trimoxazole | sul2 | DQ464881.1 | Dihydropteroate synthetase type 2 | 96 |

| sul1 | AJ698325.1 | Dihydropteroate synthetase type 1 | 72 | |

| dfrA17 | AF169041.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 17 | 33 | |

| dfrA14 | AJ313522.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 14 | 20 | |

| dfrA1 | AJ884723.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 1 | 13 | |

| sul3 | AJ459418.2 | Dihydropteroate synthetase type 3 | 10 | |

| dfrA12 | AB154407.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 12 | 4 | |

| dfrA5 | AB188269.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 5 | 3 | |

| dfrA7 | AB161450.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 7 | 3 | |

| dfrA19 | AJ310778.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 19 | 2 | |

| dfrA15 | Z83311.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase type 15 | 1 |

Table 2.

In detail comparison between the microarray-based genotype and the phenotype obtained by a VITEK-2 system.

| AMR genotype detected by microarraya | Expected AMR phenotype | Frequency of genotype detected by microarray | Detected phenotype | Concordance of expected AMR phenotype (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic tested | Resistant | Susceptible | Concordance (%) | Antibiotic tested | Resistant | Susceptible | Concordance (%) | Antibiotic tested | Resistant | Susceptible | Concordance (%) | Antibiotic tested | Resistant | Susceptible | Concordance (%) | Antibiotic tested | Resistant | Susceptible | Concordance (%) | ||||

| blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M9, blaTEM | Carbapenem resistant | 5 | MEMb | 5 | 0 | 100 | IMP | 5 | 0 | 100 | CTX | 5 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 5 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 5 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaOXA-181, blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM, blaOXA-1, blaCMY | Carbapenem resistant | 1 | MEM | 1 | 0 | 100 | IMP | 1 | 0 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 6 | 6 | 0 | 100 | 6 | 0 | 100 | 6 | 0 | 100 | 6 | 0 | 100 | 6 | 0 | 100 | 100 | |||||||

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM | 3G cephalosporin resistantc | 53 | MEM | 0 | 53 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 53 | 100 | CTX | 53 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 53 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 53 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM, blaOXA-1, blaCMY | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 16 | MEM | 0 | 16 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 16 | 100 | CTX | 16 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 16 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 16 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15 | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 12 | MEM | 0 | 12 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 12 | 100 | CTX | 12 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 12 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 12 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaOXA-1 | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 10 | MEM | 0 | 10 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 10 | 100 | CTX | 10 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 10 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 10 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM, blaCMY | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 4 | MEM | 0 | 4 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 4 | 100 | CTX | 4 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 4 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 4 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM, blaOXA-1 | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 3 | MEM | 0 | 3 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 3 | 100 | CTX | 3 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 3 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 3 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaCMY | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaMOX-CMY9, blaTEM | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM, blaOXA-7 | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M1/15, blaTEM, blaSHV | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaCTX-M9 | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaTEM (consensus), blaCMY | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| blaTEM (consensus) | 3G cephalosporin resistant | 3 | MEM | 0 | 3 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 3 | 100 | CTX | 3 | 0 | 100 | CAZ | 3 | 0 | 100 | Amp | 3 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 107 | 0 | 107 | 100 | 0 | 107 | 100 | 107 | 0 | 100 | 107 | 0 | 100 | 107 | 0 | 100 | 100 | |||||||

| blaOXA-1 | NSBL | 1 | MEM | 0 | 1 | 100 | IMP | 0 | 1 | 100 | CTX | 1 | 0 | 0 | CAZ | 1 | 0 | 0 | Amp | 1 | 0 | 100 | 60 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 100 | 60 | |||||||

| aac3lVa | Aminoglycoside resistant | 20 | CN | 20 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 20 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aac6lb | Aminoglycoside resistant | 5 | CN | 5 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 5 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aadA1 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 11 | CN | 1 | 10 | 90 | TOB | 1 | 10 | 90 | 90 | ||||||||||||

| aadA1, aac3lVa | Aminoglycoside resistant | 1 | CN | 1 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aadA2, aadA4 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 1 | CN | 0 | 1 | 0 | TOB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| aadA4 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 2 | CN | 1 | 1 | 50 | TOB | 1 | 1 | 50 | 50 | ||||||||||||

| aadA4, aac6lb | Aminoglycoside resistant | 25 | CN | 22 | 3 | 88 | TOB | 25 | 0 | 100 | 94 | ||||||||||||

| aadB, aadA1 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 1 | CN | 0 | 1 | 0 | TOB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| aphA | Aminoglycoside resistant | 6 | CN | 0 | 6 | 100 | TOB | 0 | 6 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aphA, aadA1 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 4 | CN | 0 | 4 | 100 | TOB | 0 | 4 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aphA, aadA1, aadA2 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 6 | CN | 6 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 0 | 6 | 0 | 50 | ||||||||||||

| aphA, aadA1, aadA4 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 1 | CN | 1 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aphA, aadA1, aadA4, aac6lb, aac3lVa | Aminoglycoside resistant | 1 | CN | 1 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| aphA, aadA1, aadA2, aadA4 | Aminoglycoside resistant | 1 | CN | 1 | 0 | 100 | TOB | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| n.d. | Aminoglycoside susceptible | 29 | CN | 9 | 20 | 69 | TOB | 9 | 20 | 69 | 69 | ||||||||||||

| 114 | 68 | 46 | 73 | 65 | 49 | 67 | 77 | ||||||||||||||||

| tetA | Tetracycline resistant | 55 | TE | 55 | 0 | 100 | TGC | 1 | 54 | 98 | 99 | ||||||||||||

| tetA, tetB | Tetracycline resistant | 14 | TE | 14 | 0 | 100 | TGC | 0 | 14 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| tetB | Tetracycline resistant | 26 | TE | 26 | 0 | 100 | TGC | 0 | 26 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| tetD | Tetracycline resistant | 6 | TE | 6 | 0 | 100 | TGC | 0 | 6 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| n.d. | Tetracycline susceptible | 13 | TE | 4 | 9 | 0 | TGC | 0 | 13 | 100 | 50 | ||||||||||||

| 114 | 105 | 9 | 80 | 1 | 113 | 100 | 90 | ||||||||||||||||

| qepA | Fluoroquinolone resistant | 14 | CIP | 14 | 0 | 100 | MXF | 14 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| qepA, qnrA1 | Fluoroquinolone resistant | 2 | CIP | 2 | 0 | 100 | MXF | 2 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| qnrA1 | Fluoroquinolone resistant | 31 | CIP | 30 | 1 | 97 | MXF | 30 | 1 | 97 | 97 | ||||||||||||

| qnrB | Fluoroquinolone resistant | 1 | CIP | 1 | 0 | 100 | MXF | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| qnrS | Fluoroquinolone resistant | 10 | CIP | 3 | 7 | 30 | MXF | 8 | 2 | 80 | 55 | ||||||||||||

| qnrS, qnrA1 | Fluoroquinolone resistant | 4 | CIP | 2 | 2 | 50 | MXF | 3 | 1 | 75 | 63 | ||||||||||||

| n.d. | Fluoroquinolone susceptible | 52 | CIP | 34 | 18 | 35 | MXF | 34 | 18 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||

| 114 | 86 | 28 | 73 | 92 | 22 | 84 | 79 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, dfrA1 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 6 | STX | 6 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 22 | STX | 22 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, dfrA17, dfrA19 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, dfrA5 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, sul3, dfrA12 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, sul3, dfrA12, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, sul3, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul3, dfrA5, dfrA7, dfrA14, dfrA15, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul3, dfrA7 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul3, dfrA7, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, dfrA1 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 7 | STX | 7 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, dfrA12, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, dfrA14 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 14 | STX | 14 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, dfrA14, dfrA15 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 4 | STX | 4 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, dfrA5 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 2 | STX | 2 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2, sul3, dfrA14 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 2 | STX | 2 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul3, dfrA14 | Co-trimoxazol resistant | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1 | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul2 | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 3 | STX | 1 | 2 | 66 | 66 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2 | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 30 | STX | 29 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| sul1, sul2, sul3 | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| dfrA14 | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| dfrA17 | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 1 | STX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| n.d. | Co-trimoxazol susceptible | 8 | STX | 0 | 8 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||

| 114 | 103 | 11 | 80 | 80 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Overall Concordance (%) | 83.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

A genotype was defined as a group of genes which have been described to confer resistance to a family of antibiotics (e.g., the genotype “aac6, aac6ib, aadA1” confers resistance to aminoglycosides). The phenotype was detected by a VITEK-2 system.

AK amikacin, CN gentamicin, TOB tobramycin, FEP cefepime, CTX cefotaxime, CAZ ceftazidime, MEM meropenem, IMP imipenem, TE tetracycline, TGC tigecycline, STX co-trimoxazole, CIP ciprofloxacin, MXF moxifloxacin.

3G cephalosporin – 3rd generation cephalosporin.

Nine different aminoglycoside resistance genes were detected by the E. coli PanType AS-1 kit (Table 1). The combinations of these genes resulted in 14 different genotypes, whereas the most prevalent genotype was aac(6′)-Ib in combination with aadA4 (n = 25). All isolates harboring this genotype were resistant to tobramycin, but three of them were susceptible to gentamicin (Table 2). Therefore, the concordance between genotype and phenotype was 94%. Five isolates, which harbored only aac(6′)-Ib, were resistant to all tested aminoglycosides. The second most frequent genotype was aac(3)-lVa (n = 20). All isolates harboring this gene were resistant to gentamicin and tobramycin and corresponded to 100% of the expected phenotype (Table 2). Six isolates harboring the gene aphA were susceptible to tobramycin and gentamicin. The detected phenotype corresponded 100% with the genotype, as the enzyme AphA does not mediate resistance against both aminoglycoside antibiotics tested (Ramirez and Tolmasky, 2010).

The most prevalent genotype for fluoroquinolone resistance was qnrA1 followed by qepA. One isolate harboring qnrA1 was sensitive to both quinolone antibiotics tested (97.0% concordance), but all isolates with detected qepA gene were resistant (100% concordance). Overall, 86 of 114 isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin and 92 against moxifloxacin. Only in 56 ciprofloxacin resistant isolates a corresponding genotype was detected. Similar results were observed for the 92 moxifloxacin resistant isolates, where only in 68 isolates a corresponding genotype was detected. The overall concordance of the detection of genes mediating fluoroquinolone resistance with phenotypic resistance was 79.0% (Table 2).

Resistance to co-trimoxazole is associated with sul and dfrA genes. All isolates with this gene combination were resistant to co-trimoxazole (Table 2). From 45 isolates without this gene combination, 34 were resistant. Therefore, the concordance of genotype and phenotype was 80.0%.

Of 114 isolates, one was resistant to fosfomycin. Such resistance is caused by mutations in ubiquitous genes (e.g., murA or glpT) or the loss of entire genes (e.g., uhpA) rather than by acquisition of distinct resistance markers and therefore the genotypes were not included into the test panel (Takahata et al., 2010; Li et al., 2015).

In summary, the overall concordance among all genotypes to expected phenotypes was 82.6% (Table 2).

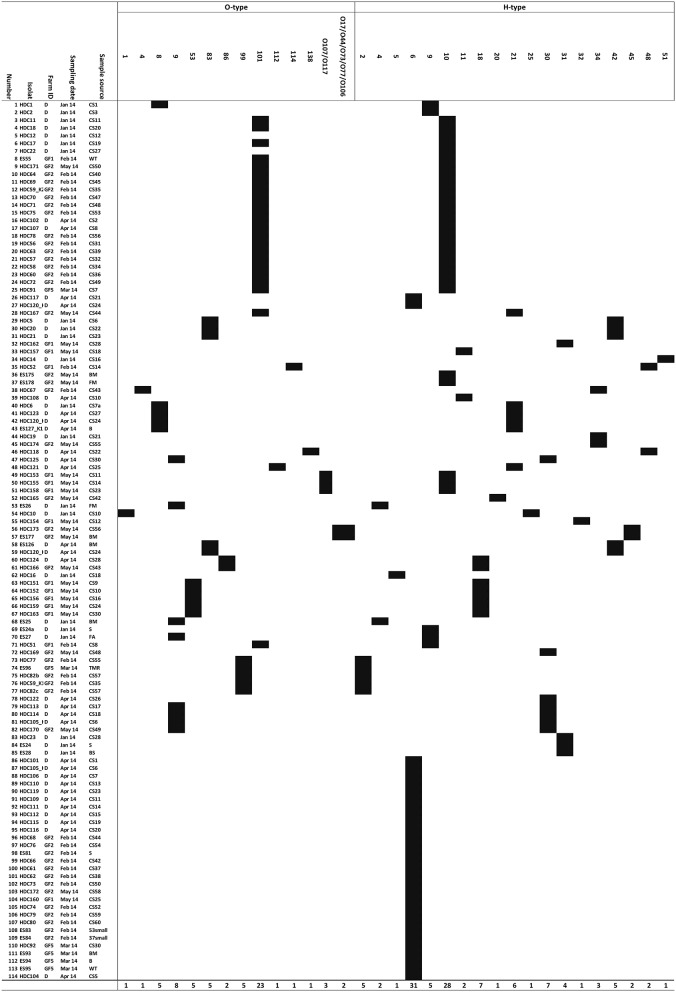

Serotyping

For all 114 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates, the O- and H-types were identified using the E. coli SeroGenotyping AS-1 kit (Figure 3). For 63 (55.3%) isolates, genes encoding both O and H antigens were detected and for 51 isolates (44.7%) only the gene encoding the H antigen could be detected. The most prevalent serotype was O101:H10. This serotype was found in locations D, GF1, and GF2 and isolated mainly from rectal swabs, as one isolate belonging to this group was found in a water trough. The AMR genotype for O101:H10 isolates was rather uniform (Figure 3). Isolates of serotype O53:H18 with the carbapenemase gene blaOXA-48 were only found in farm GF1 and were isolated from rectal swabs. All isolates belonging to this group were identical with regard to their phenotype and genotypes (Table 2, Figures 2, 3). The serotype O8:H9 with blaOXA-181 was found only once in farm D from a rectal swab. For isolates where only the H-antigen H6 was found, a very similar AMR genotypes was detected. Such isolates were found in all investigated farms and sample types.

Figure 3.

Overview of microarray-based serotyping. Serotype of all E. coli isolates obtained from swab samples (healthy dairy cattle and/or environment). Also given are the farm IDs, sample sources and sampling dates. (Abbreviations: CS, rectal swab; WT, water trough; BM, bulk milk; S, soil; FM, feed mixer; FA, feed animal; BS, boot swab; B, bedding; TMR, total mixed ration).

Discussion

In 2014, four dairy farms in northern Egypt were investigated for ESBL-producing E. coli. In total, 210 clinically healthy dairy cattle were sampled using rectal swabs. Additionally, 56 environmental swabs were taken from different stall objects and screened for multi-drug resistant bacteria. All swabs were pre-cultured on Brilliance™ ESBL Agar, and in 114 of 266 samples (42.8%), ESBL-producing E. coli were detected. To analyze the underlying molecular AMR mechanism, all 114 isolates were genotyped using the multiplex microarray technique. The most frequently detected gene which mediated resistance against 3G cephalosporins was blaCTX-M1/15 (90.4%). The genes blaCTX-M9 (5.3%) and blaTEM (78%), which also mediate resistance to 3G cephalosporins, were also detected. However, both were usually found in combination with blaCTX-M1/15. BlaCTX-M9 was related to resistance to 3G cephalosporins in just one isolate as well as blaTEM in four isolates. A comparison to data similar to data from this study is difficult due to missing reports from Egypt. Recently, two reports from Germany are known describing the prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria in livestock of healthy animals (Schmid et al., 2013; Dahms et al., 2015). Like in the present study, in both reports the most prevalent ESBL group was CTX-M. Schmid et al. (2013) collected a total of 598 samples that yielded 196 ESBL-producing E. coli (32.8%). The high percentage of ESBL-producing E. coli in healthy animals shows the high zoonotic risk for people working in close contact to animals. With this background Dahms et al. (2015) investigated different farms for ESBL-producing bacteria in samples collected from livestock and also from farm workers. In total, 70.6% of the tested farms and 5.8% of the farm workers were positive for ESBL-producing bacteria. In contrast, a study from Burgundy in France in 2012 showed only a low prevalence, of about 5%, of ESBL-producing bacteria in feces samples from different farms (Hartmann et al., 2012).

Due to the preselection of all samples on Brilliance™ ESBL agar, carbapenem resistant isolates were also retrieved. In six isolates, carbapenemase genes were detected using the CarbDetect AS-1 kit. In five isolates from a stall on farm GF1, blaOXA-48 was found. These isolates were phenotypically and genotypically identical. Interestingly, another isolate was found containing blaOXA-181, a gene belonging to the blaOXA-48-like family. Both genes are also widely distributed in human pathogens that cause hospital-acquired infection (Poirel et al., 2012). Carbapenems are last-line antibiotics with a broad spectrum and a high efficacy, and are stable against ESBLs. As they can only be administered intravenously, carbapenems are used exclusively in the clinical environment, and are not known to be used in animal husbandry. While carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are mostly described in hospitalized humans (Nordmann et al., 2011; Abdallah et al., 2015b), the current study shows conclusively that such CREs are also found in farm animals including apparently healthy dairy cattle. The detection of carbapenem resistant isolates in such an environment and the threat that such multi-drug resistance bacteria ends up in consumer food (e.g., milk or dairy products), raises serious concerns about public health. Carbapenemase-producing isolates have been detected in poultry farms (Abdallah et al., 2015a), but there are to date no reports describing finding of these multi-drug resistant bacteria in dairy cattle farms in Egypt.

Given that the majority of samples that contained ESBL/carbapenemase-producing bacteria originated from rectal swabs, this raises the question of how the potentially contaminated feces are disposed of. Normally, dung is used as fertilizer in agriculture. Via this route, multi-drug resistant pathogens might get into the food chain, either directly through consumption of meat, or indirectly from cattle grazing on fertilized pasture. Another major problem raises up in this context, the resistance genes described in this paper are usually found on plasmids (Chanawong et al., 2001; Paterson and Bonomo, 2005; Duan et al., 2006; Wittum et al., 2010; Brolund, 2014; Hansen et al., 2014; Valentin et al., 2014) and such mobile elements can be easily transferred to and between environmental bacteria (Aminov, 2011; Berglund, 2015), as well as to other human pathogens (Pitout et al., 2015). This poses a high risk to the environment, and the human population.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first report which analyses the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in Egyptian dairy farms based on genotyping and phenotyping data. The high percentage of ESBL-positive isolates and even of carbapenemase-producing bacteria was alarming given the relevance of 3G cephalosporins and carbapenems in modern medicine. Additionally, the isolates had a highly diverse genetic background with regard to serotype, virulence and antimicrobial resistance markers (Figures 2, 3). Experiments showed a high degree of concordance between genotype and phenotype.

Strict hygiene measures are mandatory to control the spread, the transmission dynamics and potential zoonotic risk factors of ESBL- and carbapenemase-producing bacteria in dairy farms.

Author contributions

SB, HE, and HH conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. SB, IE, and DW carried out the genotyping and serotyping. SB and IE carried out the antimicrobial resistance pattern by VITEK-2. MA and HE participated in sampling. HE, HH, and MA participated in preliminary design as well as bacteriological analysis of part of the study. SB, SM, HE, HH, and RE drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

SB, DW, SM, IE, and RE are employees of Alere Technologies GmbH, the company that manufactures the microarrays also used in this study. This has no influence on study design, data collection and analysis, and this does not alter the authors' adherence to all the Frontiers policies on sharing data and materials. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keri Clack (Alere Technologies, Jena, Germany) for proof reading the manuscript, Annett Reißig (Alere Technologies, Jena, Germany) and Elke Müller (Alere Technologies, Jena, Germany) for excellent technical support, Christina Braun for continuous support as well as for proof reading of the manuscript.

References

- Abdallah H. M., Reuland E. A., Wintermans B. B., Al Naiemi N., Koek A., Abdelwahab A. M., et al. (2015a). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and/or carbapenemases-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from retail chicken meat in Zagazig, Egypt. PLoS ONE 10:e0136052. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah H. M., Wintermans B. B., Reuland E. A., Koek A., al Naiemi N., Ammar A. M., et al. (2015b). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from Egyptian patients with suspected blood stream infection. PLoS ONE 10:e0128120. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham S., Chapman T. A., Zhang R., Chin J., Mabbett A. N., Totsika M., et al. (2012). Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli strains that cause symptomatic and asymptomatic urinary tract infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1027–1030. 10.1128/JCM.06671-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminov R. I. (2011). Horizontal gene exchange in environmental microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2:158. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund B. (2015). Environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and correlation to anthropogenic contamination with antibiotics. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 5:28564. 10.3402/iee.v5.28564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford P. A. (2001). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 933–951. 10.1128/CMR.14.4.933-951.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun S. D., Monecke S., Thurmer A., Ruppelt A., Makarewicz O., Pletz M., et al. (2014). Rapid identification of carbapenemase genes in gram-negative bacteria with an oligonucleotide microarray-based assay. PLoS ONE 9:e102232. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinas L., Moreno M. A., Zarazaga M., Porrero C., Saenz Y., Garcia M., et al. (2003). Detection of CMY-2, CTX-M-14, and SHV-12 beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli fecal-sample isolates from healthy chickens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 2056–2058. 10.1128/AAC.47.6.2056-2058.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolund A. (2014). Overview of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae from a Nordic perspective. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 4, 1–9. 10.3402/iee.v4.24555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A. (2008). Animal reservoirs for extended spectrum beta-lactamase producers. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl. 1), 117–123. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanawong A., M'Zali F. H., Heritage J., Lulitanond A., Hawkey P. M. (2001). SHV-12, SHV-5, SHV-2a and VEB-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Gram-negative bacteria isolated in a university hospital in Thailand. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 839–852. 10.1093/jac/48.6.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahms C., Hubner N. O., Kossow A., Mellmann A., Dittmann K., Kramer A. (2015). Occurrence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in livestock and farm workers in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. PLoS ONE 10:e0143326. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahshan H., Abd-Elall A. M., Megahed A. M., Abd-El-Kader M. A., Nabawy E. E. (2015). Veterinary antibiotic resistance, residues, and ecological risks in environmental samples obtained from poultry farms, Egypt. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187, 1–10. 10.1007/s10661-014-4218-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan R. S., Sit T. H., Wong S. S., Wong R. C., Chow K. H., Mak G. C., et al. (2006). Escherichia coli producing CTX-M beta-lactamases in food animals in Hong Kong. Microb. Drug Resist. 12, 145–148. 10.1089/mdr.2006.12.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamarellou H. (2005). Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11(Suppl. 4), 1–16. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haftu R., Taddele H., Gugsa G., Kalayou S. (2012). Prevalence, bacterial causes, and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of mastitis isolates from cows in large-scale dairy farms of Northern Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 44, 1765–1771. 10.1007/s11250-012-0135-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K. H., Bortolaia V., Damborg P., Guardabassi L. (2014). Strain diversity of CTX-M-producing Enterobacteriaceae in individual pigs: insights into the dynamics of shedding during the production cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6620–6626. 10.1128/AEM.01730-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A., Locatelli A., Amoureux L., Depret G., Jolivet C., Gueneau E., et al. (2012). Occurrence of CTX-M producing Escherichia coli in soils, cattle, and farm environment in France (Burgundy Region). Front. Microbiol. 3:83. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISO (2001). ISO 16654:2001 Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs – Horizontal Method for the Detection of Escherichia coli O157 [Online]. Geneve. Available online at: http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=29821 [Accessed]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li Y., Zheng B., Zhu S., Xue F., Liu J. (2015). Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolates in mainland China. PLoS ONE 10:e0135269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann P., Naas T., Poirel L. (2011). Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerging Infect. Dis. 17, 1791–1798. 10.3201/eid1710.110655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson D. L., Bonomo R. A. (2005). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 657–686. 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout J. D., Nordmann P., Poirel L. (2015). Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 5873–5884. 10.1128/AAC.01019-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Potron A., Nordmann P. (2012). OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 1597–1606. 10.1093/jac/dks121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M. S., Tolmasky M. E. (2010). Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updat. 13, 151–171. 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat D., Nair D. (2010). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in gram negative bacteria. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2, 263–274. 10.4103/0974-777X.68531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A., Hörmansdorfer S., Messelhausser U., Käsbohrer A., Sauter-Louis C., Mansfeld R. (2013). Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli on Bavarian dairy and beef cattle farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3027–3032. 10.1128/AEM.00204-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh S., Fatima J., Shakil S., Rizvi S. M., Kamal M. A. (2015). Antibiotic resistance and extended spectrum beta-lactamases: types, epidemiology and treatment. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 22, 90–101. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata S., Ida T., Hiraishi T., Sakakibara S., Maebashi K., Terada S., et al. (2010). Molecular mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35, 333–337. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin L., Sharp H., Hille K., Seibt U., Fischer J., Pfeifer Y., et al. (2014). Subgrouping of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli from animal and human sources: an approach to quantify the distribution of ESBL types between different reservoirs. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304, 805–816. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2013). Consultative Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance for Countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: From Policies to Action [Online]. Sharm El Sheikh. Available online at: http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/IC_Meet_Rep_2014_EN_15210.pdf [Accessed 2013].

- Wittum T. E., Mollenkopf D. F., Daniels J. B., Parkinson A. E., Mathews J. L., Fry P. R., et al. (2010). CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases present in Escherichia coli from the feces of cattle in Ohio, United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7, 1575–1579. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]