Abstract

The amyloid-β peptide (Aβ)—in particular, the 42–amino acid form, Aβ1-42—is thought to play a key role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Thus, several therapeutic modalities aiming to inhibit Aβ synthesis or increase the clearance of Aβ have entered clinical trials, including γ-secretase inhibitors, anti-Aβ antibodies, and amyloid-β precursor protein cleaving enzyme inhibitors. A unique class of small molecules, γ-secretase modulators (GSMs), selectively reduce Aβ1-42 production, and may also decrease Aβ1-40 while simultaneously increasing one or more shorter Aβ peptides, such as Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37. GSMs are particularly attractive because they do not alter the total amount of Aβ peptides produced by γ-secretase activity; they spare the processing of other γ-secretase substrates, such as Notch; and they do not cause accumulation of the potentially toxic processing intermediate, β-C-terminal fragment. This report describes the translation of pharmacological activity across species for two novel GSMs, (S)-7-(4-fluorophenyl)-N2-(3-methoxy-4-(3-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)-N4-methyl-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (BMS-932481) and (S,Z)-17-(4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-34-(3-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-16,17-dihydro-15H-4-oxa-2,9-diaza-1(2,4)-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidina-3(1,3)-benzenacyclononaphan-6-ene (BMS-986133). These GSMs are highly potent in vitro, exhibit dose- and time-dependent activity in vivo, and have consistent levels of pharmacological effect across rats, dogs, monkeys, and human subjects. In rats, the two GSMs exhibit similar pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics between the brain and cerebrospinal fluid. In all species, GSM treatment decreased Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 levels while increasing Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 by a corresponding amount. Thus, the GSM mechanism and central activity translate across preclinical species and humans, thereby validating this therapeutic modality for potential utility in AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of senile dementia, placing a huge burden on patients, their families, and caregivers (Wimo and Prince, 2010). Treatments for symptoms are available, but have limited benefit, and do not prevent or slow the progression of AD (Prince et al., 2011). The causes of AD are not fully understood, but evidence from human genetics, brain pathology, and experimental models has converged on the amyloid hypothesis (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). This hypothesis implicates the accumulation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) in the brain, particularly the neurotoxic 42–amino acid form, Aβ1-42, as a key factor in the disease (Findeis, 2007). A major therapeutic objective has therefore been to inhibit the synthesis of, neutralize, or clear Aβ from the brain. Direct pharmacological targets include the proteolytic enzymes, amyloid-β precursor protein cleaving enzyme and γ-secretase, responsible for Aβ production by cleavage of the amyloid-β precursor protein (APP; Karran et al., 2011), and Aβ itself using anti-Aβ antibodies (Karran, 2012). However, success in the clinic has been elusive, potentially because the drugs so far have had an insufficient impact on Aβ-lowering at clinically tolerable doses (Toyn and Ahlijanian, 2014).

γ-Secretase modulators (GSMs) are small molecules that are of particular interest because they selectively decrease Aβ1-42 production. GSMs bind to presenilin, the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase (Crump et al., 2011; Ebke et al., 2011; Ohki et al., 2011; Jumpertz et al., 2012; Pozdnyakov et al., 2013), and alter the amino acid positions at which substrate proteolysis takes place, resulting in the generation of a greater proportion of shorter Aβ peptides, such as Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37, relative to the longer peptides Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40. An attractive feature of GSMs is that their effect on Aβ peptides is essentially opposite that of presenilin mutations that cause familial AD (FAD). In presenilin FAD mutants, the proportion of Aβ1-42 relative to the levels of other Aβ peptides is increased, and is associated with earlier age of onset (Duering et al., 2005; Kumar-Singh et al., 2006; Okochi et al., 2013). Thus, GSMs shift Aβ peptide production in a direction opposite that of FAD, implying that GSMs have the potential to delay onset of dementia.

GSM activity was originally described for several nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; Weggen et al., 2001). Subsequently, many other small molecules and natural products have been reported to exhibit selective lowering of Aβ1-42 (for review, see Tate et al., 2012). In general, the NSAIDs and their derivatives decrease Aβ1-42 and increase Aβ1-38, while having no effect on Aβ1-40 production. Other GSMs, with chemical structures unrelated to the NSAIDs (Caldwell et al., 2010; Kounnas et al., 2010; Wan et al., 2011a,b; Borgegard et al., 2012; Tate et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2014), decrease Aβ1-40 in addition to Aβ1-42, while simultaneously increasing one or more of the shorter peptides Aβ1-37, Aβ1-38, or Aβ1-39. The common element of all GSMs is that they decrease Aβ1-42 without inhibition of overall Aβ1-x production. GSMs have two advantages that derive from the lack of γ-secretase inhibition: first, they avoid inhibition of the many other protein substrates of γ-secretase (Haapasalo and Kovacs, 2011), and second, they avoid accumulation of the potentially toxic APP C-terminal fragments in the brain (Mitani et al., 2012, 2014). Low-potency NSAID GSMs, such as flurbiprofen, were reported to lower brain Aβ1-42 in some, but not all, studies in rodents (Eriksen et al., 2003; Lanz et al., 2005; Kukar et al., 2007). However, in clinical trials, flurbiprofen (tarenflurbil) had no effect on Aβ1-42 levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) even at high doses (Galasko et al., 2007). High-potency GSMs have also entered early-stage clinical trials, but effects on Aβ in CSF have not been reported (Nakano-Ito et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014). Thus, lowering of central nervous system Aβ1-42 by GSMs has not been demonstrated previously in clinical trials.

(S)-7-(4-fluorophenyl)-N2-(3-methoxy-4-(3-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)-N4-methyl-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (BMS-932481) and (S,Z)-17-(4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-34-(3-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-16,17-dihydro-15H-4-oxa-2,9-diaza-1(2,4)-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidina-3(1,3)-benzenacyclononaphan-6-ene (BMS-986133) are novel bicyclic pyrimidines (Supplemental Fig. 1) related to analogs that were initially identified in a high-throughput screen (Toyn et al., 2014). Here, we show that GSM mechanism and Aβ-lowering activity exhibit excellent translation across species. In rats, brain and CSF pharmacodynamics were found to be very similar, and the effects on CSF Aβ peptides were found to be remarkably consistent between rats, dogs, monkeys, and healthy human subjects. BMS-932481 was chosen for clinical development, and provided a robust demonstration of GSM mechanism and central activity in human subjects.

Materials and Methods

Compounds.

The novel GSMs BMS-932481 and BMS-986133 were prepared at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, CT, using methods reported in Bristol-Myers Squibb patents (Boy et al. 2014a, b). The γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) used for comparisons in some experiments, (R)-4-(2-(1-((4-chloro-N-(2,5-difluorophenyl)phenyl)sulfonamido)ethyl)-5-fluorophenyl)butanoic acid (BMS-299897; Barten et al., 2005) and (R)-2-((4-chloro-N-(2-fluoro-4-(1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)benzyl)phenyl)sulfonamido)-3-cyclopropylpropanamide (BMS-698861; Toyn et al., 2014), have been described previously.

Aβ and Notch Assays.

In overview, Aβ peptides were quantified using a range of different immunoassays, using antibodies that are specific for the free C-terminal amino acids of Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, or Aβ1-37 (Toyn et al., 2014). Immunoassays for Aβ1-x used antibodies that are not selective for the free C-terminal amino acid, and therefore measured the sum of the Aβ peptides including Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37. Aβx-42 represents an immunoassay capable of detecting N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides while being selective for the C-terminal amino acid at position 42. The homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence immunoassays for Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 in H4-APPsw cell cultures and the Notch1 and Notch3 cell culture assays have been described previously (Gillman et al., 2010). The automated multiplex assay for simultaneous quantification of Aβx-42 and Aβ1-x in H4-APPsw cell cultures used a high-throughput homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence method in 1736-well format that will be described in detail elsewhere. In brief, Aβx-42 was detected by a combination of the monoclonals 4G8 (Aβ17-24 epitope; Covance, Princeton, NJ) and 565 (Aβ42 C-terminal cleaved epitope; Bristol-Myers Squibb), and therefore represents full-length and N-terminally truncated Aβ peptides that have a C-terminal amino acid corresponding to position 42. Aβ1-x was simultaneously detected in the same assay wells by a combination of the monoclonals 4G8 and 26D6 (human Aβ1-12 epitope; Bristol-Myers Squibb), and therefore represents full-length and C-terminally truncated Aβ peptides. The mesoscale 3-plex and 4-plex immunoassays and the Aβ1-x enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were carried out as previously described (Toyn et al., 2014). The Aβ1-x ELISA used a combination of monoclonal 4G8, with 252Q6–horseradish peroxidase conjugate for rat or 26D6–horseradish peroxidase for monkey and human. For rat brain and CSF, Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 were quantified using conventional singleplex ELISA assays using appropriate combinations of monoclonals and enzyme-labeled conjugates. For dog and monkey CSF, Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 were quantified using the mesoscale 4-plex assay. For human subjects, Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, and Aβ1-38 were quantified using the mesoscale 3-plex assay, and Aβ1-37 was quantified by ELISA using a combination of 26D6 and an Aβ1-37–selective rabbit polyclonal antibody (antibody provided by Pankaj Mehta, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY). Concentrations of Aβ peptides were determined by fitting the immunoassay readouts against calibration curves derived from a range of dilutions of the corresponding synthetic peptides on each assay plate using a quadratic curve fit. Results were expressed in picomolar units corrected for sample dilution. The immunoprecipitation-matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectroscopy assays for Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 were carried out as previously described (Toyn et al., 2014).

BMS-932481 Analytical Methods.

BMS-932481 concentrations in animal plasma and brain samples were analyzed using an ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (MS-MS) method. The ultra-performance liquid chromatography–MS-MS system consisted of a Waters Acquity Ultra Performance LC Sample Organizer, Solvent Manager, and Sample Manager (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA); a Waters BEH C18, 1.7 µm, 130Å, 2.1 mm × 50 mm column operated at 60°C; and a SCIEX API 4000 QTRAP mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Concord, Ontario, Canada). The mobile phase consisted of (A) water with 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, delivered at 700 µl/min using a gradient program. The initial elution condition was 5% B, which was maintained for 0.2 minute and increased to 95% B in 0.3 minute and maintained for 0.5 minute. It was then returned to 5% B in 0.1 minute and maintained for 0.2 minute. The MS-MS analysis was performed using turbo spray under positive ion mode with the source temperature at 600°C. The capillary voltage was 5500 eV, and the collision energy was 47 eV. Mass-to-charge ratios of 447 (precursor ion) and 431 (product ion) were used for multiple reaction mode monitoring of BMS-932481. The quantitation range for BMS-932481 was 10–5000 nM. Plasma samples were deproteinized and extracted with four portions of acetonitrile.

Animals and Dosing.

All experimental procedures with animals followed National Institutes of Health guidelines and were authorized by and in compliance with the policies of the Bristol-Myers Squibb Animal Use and Care Committee. Animals were housed with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and allowed free access to food and water. For pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) in rats, 10- to 12-week-old female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were dosed with BMS-932481 (1, 5, and 10 mg/kg), BMS-986133 (2.5, 5, and 15 mg/kg), or vehicle alone by intravenous injection at 1.5 ml/kg in vehicle consisting of polyethylene glycol with an average molecular weight of 400, ethanol, and Solutol HS 15 at a ratio of 93:5:2 (w/w/w). Rats were fasted between 16 hours prior to and 4 hours after dosing. Dosing was carried out in a randomized order within each time group (randomizing vehicle group, and all BMS-932481 and BMS-986133 dose groups together). Groups of rats (n = 4) were euthanized by asphyxiation in CO2 at 10 minutes, 30 minutes, and 1, 3, 7, 12, and 24 hours after dosing. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and placed into EDTA microtainer tubes for the preparation of plasma. CSF was collected from cisterna magna by syringe, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes, and supernatant was frozen in liquid nitrogen. Brain was separated into left and right halves, without the cerebellum, before freezing in liquid nitrogen. Distribution of BMS-932481 into rat brain was evaluated following oral administration of BMS-932481 and formulated at 10 mg/kg in polyethylene glycol with an average molecular weight of 400, Solutol, and D-a-tocopherol polyethylene glycol succinate at a ratio of 90:5:5 (w/w/w). Groups of rats (n = 3) were harvested at 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours postdose, and blood samples were collected from the jugular vein into EDTA-containing tubes and centrifuged at 4°C (1500–2000 × g) to obtain plasma. Brain tissues were blotted dry, weighed, and homogenized with 4 volumes of sodium phosphate-buffered saline. The cerebellum was used for analysis of BMS-932481 levels. All samples were stored at −20°C before analysis by liquid chromatography–MS/MS.

For the dog CSF study, male beagle dogs (∼1 year old; 8–11 kg) were implanted with an indwelling lumbar catheter to facilitate CSF collection from conscious, lightly restrained animals. Animals were singly housed, water was provided ad libitum, and food was provided once a day in the morning. The dogs were fasted 16 hours prior to dosing, and food was reintroduced 4 hours postdose. A total of four dogs were included in this experiment, which used a crossover design, with a 1-week washout period between doses. In each given week, the assignment of dog to dose group was determined randomly. The dogs were dosed with BMS-932481 at 2, 5, and 30 mg/kg, or vehicle alone. Each dog had received all doses and vehicle at the completion of the experiment. Blood was collected from each dog at the following times relative to dosing: −24, −16, 0 (predose), 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours, and CSF was collected at −24, −16, 0 (predose), 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours. BMS-932481-02 (HCl salt) was dosed by oral gavage (2 ml/kg) as a suspension prepared in vehicle containing 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone K 30, 0.01% Tween 80, 0.01 M HCl, and 0.09 M NaCl. All dosing was completed within 3 hours of compound formulation. Blood (2 or 4 ml) was collected from either the saphenous or cephalic vein into EDTA vacutainer tubes. CSF (0.2 ml) was collected from the lumbar catheter port into a low-protein binding polypropylene tube after the catheter dead volume was discarded (∼ 0.2 ml). After each collection, the lumbar catheters were flushed with 0.3 ml of 0.9% sterile saline. Blood and CSF samples were kept on ice until centrifugation. Blood was centrifuged at 2880 × g for 10 minutes. The plasma was collected for determination of compound levels. CSF samples were centrifuged at 1330 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

For the monkey CSF study, male cynomolgus monkeys (∼1 year old; 5–6 kg) were implanted with an indwelling lumbar catheter. Monkeys were singly housed, water was provided ad libitum, and food was provided once a day in the morning. Prior to dosing, animals were fasted overnight, within 16 ± 2 hours prior to dosing. Food was reintroduced 4 hours postdose. A total of four monkeys were included in this experiment, which used a crossover design, with a 1-week washout period between doses. In each given week, the assignment of monkeys to doses or vehicle alone was determined randomly. Monkeys were dosed with BMS-986133 at 5 or 15 mg/kg, or vehicle alone. At the completion of the experiment, all four monkeys had received vehicle and both doses. Blood was collected from each monkey at the following times relative to dosing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 30 minutes, and 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 24, and 48 hours, and CSF was collected at −24, 0 (predose), 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 24, and 48 hours. Plasma and CSF samples were prepared and stored as described for the dog study.

Single-Dose Study in Human Subjects.

Studies in human subjects were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review boards. Oral doses of BMS-932481 were given to human subjects in a single ascending dose study, in which subjects received doses of BMS-932481 ranging from 10 to 1200 mg. The single ascending dose study was designed and executed as a placebo-controlled, double-blinded study in healthy young subjects, and is described in detail in the accompanying manuscript by Soares et al. (2016). In one of the dose panels, longitudinal CSF samples were collected. This panel included 15 healthy young male and female subjects of non–child-bearing potential, who were given a single 900-mg oral dose of BMS-932481, or placebo, in the fasted state, and longitudinal CSF samples were collected via indwelling lumbar catheter at the following time points relative to dosing: −1, 0 (predose), 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 15, 18, and 24 hours.

Results

In Vitro Effects of the GSM, BMS-932481, on Aβ Peptides and Notch.

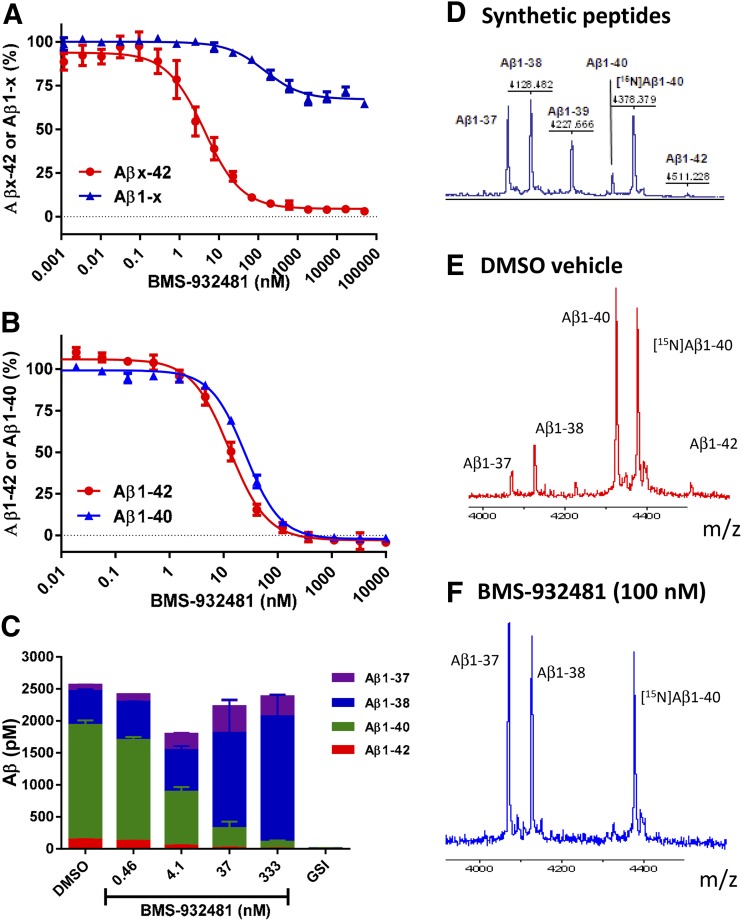

H4-APPsw cell cultures were treated overnight with BMS-932481 at a range of concentrations to determine the dose response. In the Aβ multiplex assays, which quantify Aβx-42 and Aβ1-x simultaneously, IC50 determinations for Aβx-42 averaged 5.5 nM, whereas Aβ1-x was reduced by no more than 30%, even at concentrations up to 50 μM (Fig. 1A). For comparison, the GSI, BMS-299897, reduced Aβx-42 and Aβ1-x with approximately equal potency in the multiplex assays (Supplemental Fig. 2). Using ELISAs for Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40, BMS-932481 potently reduced Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 levels, yielding IC50 values of 6.6 and 25.3 nM, respectively (Fig. 1B). Further evaluation of Aβ peptides using Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 immunoassays showed that, although BMS-932481 decreased Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40, it increased Aβ1-37 and Aβ1-38 by an approximately corresponding amount. Despite the dramatic changes in the levels of individual peptides, there was little if any effect on the overall level of Aβ (Fig. 1C). For comparison, the GSI, BMS-299897, inhibited production of all four Aβ peptides (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

In vitro activity of BMS-932481. (A) H4-APPsw cell cultures were incubated overnight with BMS-932481 at a range of concentrations from 1 pM to 50 μM. Aβx-42 and Aβ1-x concentrations were determined simultaneously using the automated multiplex homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assays. Error bars show standard error for seven independent assays. IC50 values (or inhibition percentage) with standard deviations are as follows: Aβx-42 IC50 = 5.5 ± 3.6 nM; Aβ1-x maximum inhibition = 30 ± 10% at 50 μM. (B) H4-APPsw cell cultures were incubated overnight with BMS-932481 at a range of concentrations from 10 pM to 10 μM. Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 were determined using automated homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assays. Error bars show standard error for three independent assays in which both Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 were determined in parallel from the same cell cultures. IC50 values with standard deviations are as follows: Aβ1-42 IC50 = 6.6 ± 2.3 nM; Aβ1-40 IC50 = 25 ± 7.9 nM. (C) H4-APPsw cell cultures were incubated overnight with BMS-932481 at a range of concentrations from 0.46 to 333 nM, 0.1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle, or GSI BMS-299897 at a concentration of 1 μM. Concentrations were determined for Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 using the 4-plex Meso Scale Diagnostics assays. Error bars indicate standard error for two replicate wells. (D) An equimolar mix of synthetic peptides, including [14N]Aβ1-40, was evaluated by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectroscopy. (E and F) H4-APPsw cell cultures were incubated overnight with 0.1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (E) or BMS-932481 (F) at a concentration of 100 nM, then Aβ peptides were immunoprecipitated and evaluated by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectroscopy.

The same changes in Aβ peptide levels can be visualized qualitatively by immunoprecipitation-matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectroscopy (Fig. 1, D–F). Peptides with the expected masses for Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 were identified in vehicle-treated H4-APPsw cell cultures (Fig. 1E). After overnight treatment with BMS-932481 at a concentration of 100 nM, no Aβ1-42 or Aβ1-40 was detected, whereas increased levels of the shorter Aβ peptides, Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37, were observed (Fig. 1F).

Cell-based transcriptional reporter assays were also carried out to assess the effect of BMS-932481 on the γ-secretase substrates Notch1 and Notch3, and IC50 values were determined to be approximately 1 μM (not shown).

γ-Secretase Modulation of Brain Aβ and CSF Aβ Peptides in Rats.

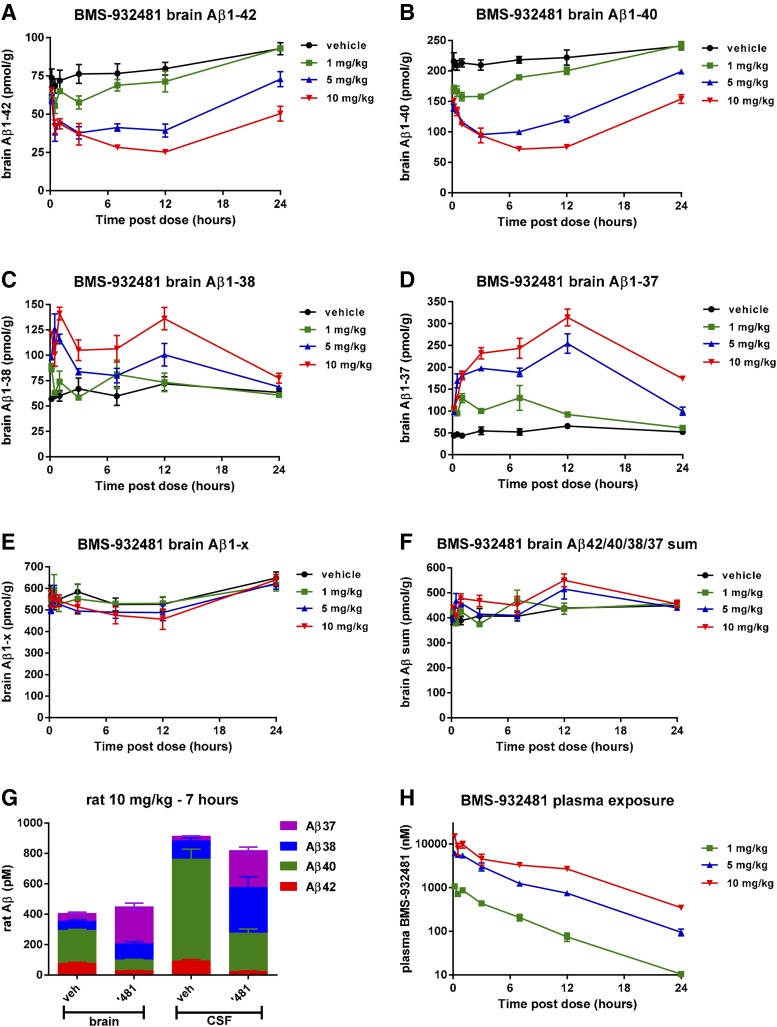

Rats were given single intravenous doses of BMS-932481 (1, 5, or 10 mg/kg) or the related compound BMS-986133 (2.5, 5, or 15 mg/kg), or were dosed with vehicle only. The potency of BMS-986133 in the H4-APPsw Aβ1-42 immunoassay (IC50 = 3.5 nM) is similar to that of BMS-932481 (IC50 = 6.6 nM). The intravenous route of administration was used to minimize interanimal variability. Dose-dependent and time-dependent decreases in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 and increases in Aβ1-37 and Aβ1-38 were observed for both compounds in both brain and CSF (Fig. 2; Supplemental Figs. 3–5). For BMS-932481, brain Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 levels were decreased by very similar amounts, to a maximum reduction of about 75% relative to vehicle-treated rats (Fig. 3, A and B). Aβ1-37 and Aβ1-38 exhibited increased levels, with ca. 2-fold maximal increase for Aβ1-38 (Fig. 2C) and ca. 6-fold maximal increase for Aβ1-37 (Fig. 2D). Aβ1-x showed no significant changes at any dose or time point (Fig. 2E). Likewise, the sum of the Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 concentrations showed no significant changes (Fig. 2F). Thus, the relative amounts of the four Aβ peptides were changed after dosing with BMS-932481, but the overall amounts of Aβ peptides remained unchanged (Fig. 2, E–G). The concentrations of BMS-932481 in blood plasma from the same rats were dose-proportional (Fig. 2H). Similar dose- and time-dependent changes in Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, Aβ1-37, and Aβ1-x peptides were observed in the CSF of BMS-932481–dosed rats (Supplemental Fig. 3). Likewise, similar profiles of dose dependence and time dependence in rats were observed for Aβ after treatment with the related GSM, BMS-986133, in brain (Supplemental Fig. 4) and CSF (Supplemental Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Altered levels of brain Aβ peptides in rats given single doses of BMS-932481. Rats were given intravenous doses of BMS-932481 at 1, 5, and 10 mg/kg, or vehicle alone. After dosing, groups (n = 4) of rats were euthanized at intervals between 10 minutes and 24 hours. Plasma, brain, and CSF samples were taken. Brain Aβ1-42 (A), brain Aβ1-40 (B), brain Aβ1-38 (C), brain Aβ1-37 (D), brain Aβ1-x (E), and the sum of brain Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 (F). (G) Stack chart showing amounts of Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 in brain and CSF of vehicle- and BMS-932481–dosed rats 7 hours after dosing. (H) Concentrations of BMS-932481 in blood plasma. Error bars indicate standard error. The concentrations of CSF Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, Aβ1-37, and Aβ1-x in the same rats are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3. The significance of treatment effects was analyzed by analysis of variance (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 3.

The effects of GSMs on Aβ levels in brain and CSF are correlated. ABEC was calculated for brain and CSF Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 at each dose of BMS-932481 and BMS-986133 in the rat study illustrated in Fig. 2 and Supplemental Figs. 3–5. (A) ABECs for CSF Aβ1-42 and CSF Aβ1-40 were plotted against the corresponding ABECs for brain Aβ1-42 and brain Aβ1-40. Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.99*x – 1.7, r2 = 0.93, P < 0.0001. (B) ABECs for CSF Aβ1-38 and CSF Aβ1-37 were plotted against the corresponding ABECs for brain Aβ1-38 and brain Aβ1-37. Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 1.4*x + 14, r2 = 0.98, P < 0.0001. (C) Scatter plot for brain Aβ1-42 and CSF Aβ1-42 from individual rats (total of 196 rats). Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.92*x + 7.9, r2 = 0.34, P < 0.0001. (D) Scatter plot for brain Aβ1-40 and CSF Aβ1-40 from individual rats. Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.922*x + 14, r2 = 0.61, P < 0.0001. (E) Scatter plot for brain Aβ1-42 and brain Aβ1-40 from individual rats. Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.82*x + 9.8, r2 = 0.78, P < 0.0001. (F) Scatter plot for CSF Aβ1-42 and CSF Aβ1-40 from individual rats. Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.81*x + 19, r2 = 0.85, P < 0.0001.

The extent of distribution of BMS-932481 into the brain in rats was evaluated in an additional time-course study (not shown). BMS-932481 exhibited moderate brain penetration. The brain-to-plasma ratio was ≥0.23 in samples collected at 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours. The ratio of brain area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) to plasma AUC was ∼0.6. In addition, immunoprecipitation–western blots indicated no effect on amyloid-β precursor protein C-terminal fragment accumulation in the brains of rats treated with BMS-932481 (Supplemental Fig. 8).

γ-Secretase Modulation of Aβ Peptides Is Closely Correlated between Brain and CSF.

To compare the pharmacology of γ-secretase modulation between brain and CSF, the area between the Aβ vehicle-dosed baseline and the Aβ effect curve (ABEC) was calculated for each dose of BMS-932481 and BMS-986133 in brain and CSF from the experiment described earlier (Fig. 2; Supplemental Figs. 3–5). For Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40, a scatter plot of CSF ABEC against brain ABEC exhibited a close linear correlation with a slope of one, indicating that the effect of GSMs on these peptides was near identical in brain and CSF (Fig. 3A). For Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37, the ABEC scatter plot also showed a close linear correlation of the effects in brain and CSF; however, the magnitude of the increase in these peptides was ca. 1.4-fold higher in CSF than in brain (Fig. 3B). This greater percentage increase in CSF relative to brain appears to be a reflection of the lower relative amount of Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 in CSF at baseline. Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 comprise approximately 17% of the Aβ in CSF, compared with 27% of Aβ in the brain (Fig. 2G).

Aβ peptide levels in brain and CSF can also be compared using scatter plots of the data from individual rats. Aβ1-42 (Fig. 3C) and Aβ1-40 (Fig. 3D) levels were significantly correlated between brain and CSF. However, considerable scatter exists on these plots, with no apparent correlation in the vehicle groups, i.e., animals not dosed with GSMs. Thus, aggregation of data, as shown using ABEC, was necessary to compare Aβ pharmacodynamics between brain and CSF. In contrast, the correlations between Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40, at the level of individual rats, in brain (Fig. 3E) and CSF (Fig. 3F) are stronger, suggesting that Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 may be equally useful as CSF biomarkers for the evaluation of GSM pharmacodynamics. The similarity in the response of Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 is unexpected, given the different potencies of in vitro inhibition by GSMs for these two peptides. Although this observation remains unexplained, it is highly reproducible.

γ-Secretase Modulation of CSF Aβ Peptides in Dog.

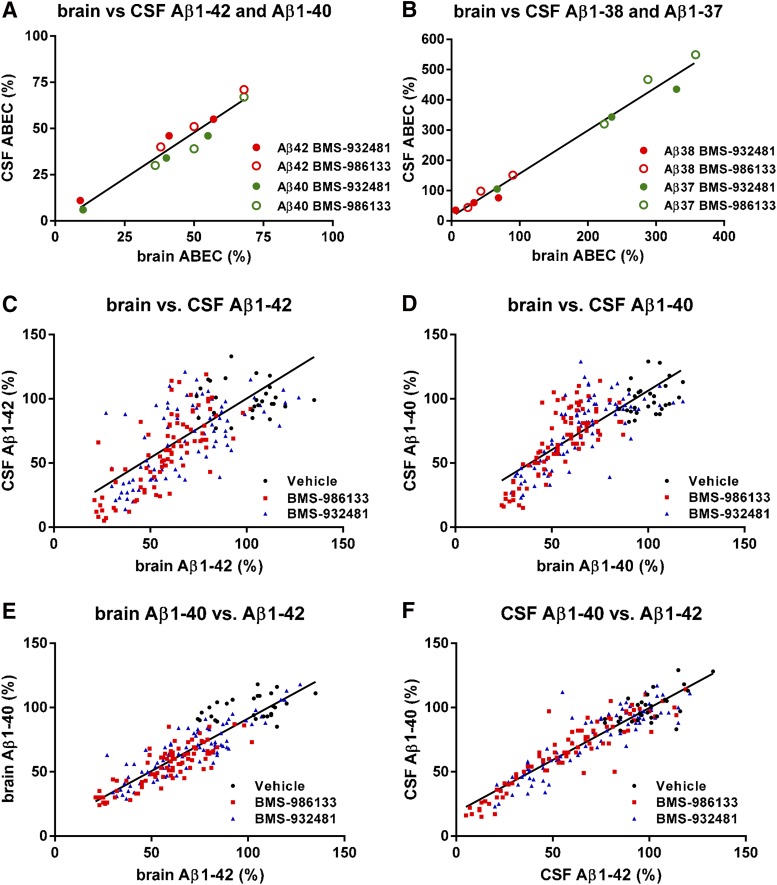

Four dogs were given oral doses of BMS-932481 at 2, 5, or 30 mg/kg, or vehicle, in a crossover study design, so that all dogs received all doses and vehicle by the end of the study. CSF samples were taken predose and at intervals postdose via indwelling catheter. A maximum reduction of Aβ1-42 (Fig. 4A) and Aβ1-40 (Fig. 4B) of ca. 65% occurred 24 hours after the 30-mg/kg dose, whereas Aβ1-38 (Fig. 4C) and Aβ1-37 (Fig. 4D) were maximally increased by 1.8-fold and 5-fold, respectively. Despite the robust effects on Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37, there was little, if any, effect on the sum of the four Aβ peptides (Fig. 4E). There was a transient rise in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 levels of vehicle-treated dogs that returned toward baseline within 24 hours. In contrast, there was little, if any, transient rise apparent in Aβ1-38 or Aβ1-37 vehicle-treated dogs. Lowering of Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 was correlated (Fig. 4F). Plasma exposure in this experiment was variable between individual dogs, and three of the four dogs in the top dose group exhibited a secondary increase in exposure at 24 hours post dose, suspected due to coprophagia (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Altered levels of CSF Aβ peptides in dogs given single doses of BMS-932481. Dogs surgically fitted with a cannula in the lumbar spinal cord were given oral doses of BMS-932481 at 2, 5, and 30 mg/kg, or vehicle alone in a cross-over study design (total of four dogs). Plasma and CSF samples were taken predose and at intervals after dosing up to 72 hours. CSF Aβ1-42 (A), CSF Aβ1-40 (B), CSF Aβ1-38 (C), CSF Aβ1-37 (D), and the sum of CSF Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 (E). (F) Scatter plot for CSF Aβ1-42 and CSF Aβ1-40 from all individual samples (total of 189 samples). Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.81*x + 20, r2 = 0.77, P < 0.0001. Error bars indicate standard error. Concentrations of BMS-932481 in blood plasma from the dogs are illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 6. The significance of treatment effects was analyzed by analysis of variance (Supplemental Table 3).

γ-Secretase Modulation of CSF Aβ Peptides in Monkey.

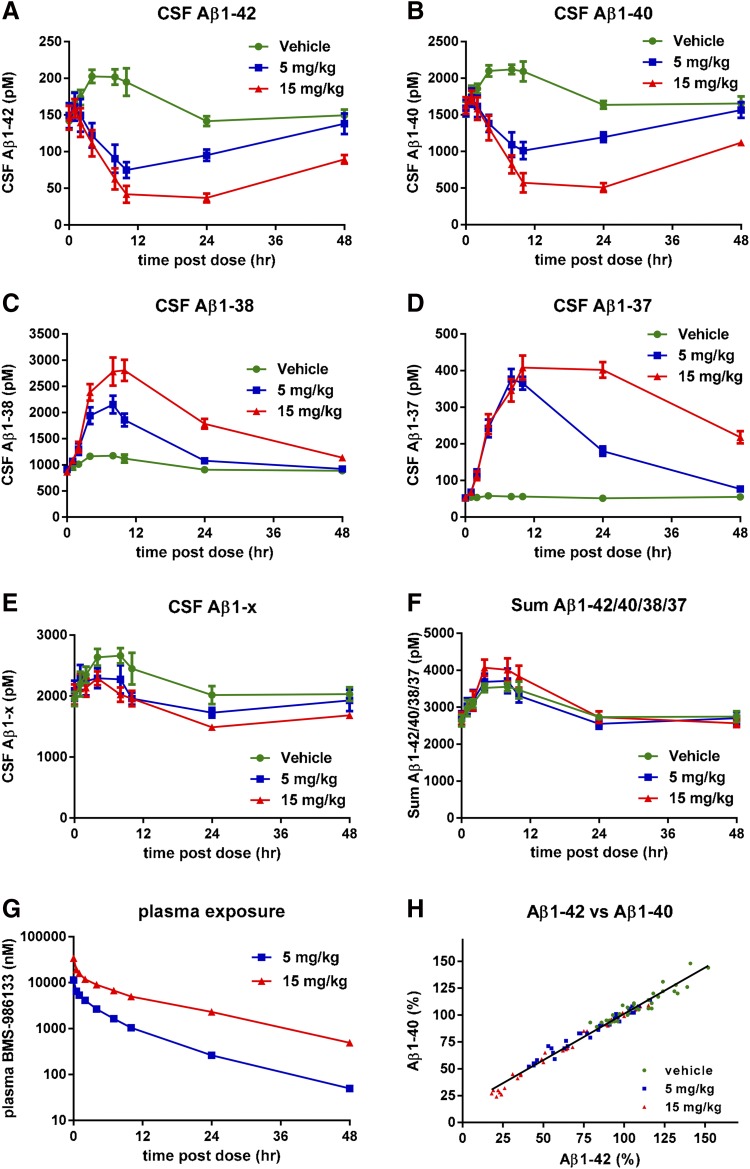

BMS-986133 is a GSM with a related chemical structure and similar potency to BMS-932481. Four monkeys were given intravenous doses of BMS-986133 at 5 or 15 mg/kg, or vehicle, in a crossover study design, so that all monkeys received all doses and vehicle. CSF samples were taken predose and at intervals postdose via indwelling catheter. A maximum reduction of Aβ1-42 (Fig. 5A) and Aβ1-40 (Fig. 5B) of ca. 75% occurred 12–24 hours after the 30-mg/kg dose, whereas Aβ1-38 (Fig. 5C) and Aβ1-37 (Fig. 5D) were maximally increased by ca. 3-fold and 8-fold, respectively. Despite the robust effects on Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37, there was little, if any, effect on levels of CSF Aβ1-x (Fig. 5E) or the sum of the four Aβ peptides (Fig. 5F). There was a transient rise in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 levels of vehicle-treated monkeys that lasted for about 24 hours, a less pronounced rise in Aβ1-38, but no apparent rise for Aβ1-37 in vehicle-treated monkeys. Concentrations of BMS-986133 in blood plasma were dose-proportional (Fig. 5G). Levels of Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 were highly correlated in individual animals (Fig. 5H).

Fig. 5.

Altered levels of CSF Aβ peptides in monkeys given single doses of BMS-986133. Monkeys surgically fitted with a cannula in the lumbar spinal cord were given intravenous doses of BMS-932481 at 5 and 15 mg/kg, or vehicle alone, in a crossover study design (total of four monkeys). Plasma and CSF samples were taken predose and at intervals after dosing up to 72 hours. CSF Aβ1-42 (A), CSF Aβ1-40 (B), CSF Aβ1-38 (C), CSF Aβ1-37 (D), CSF Aβ1-x (E), and the sum of Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 (F). (G) Concentrations of BMS-932481 in blood plasma. (H) Scatter plot for CSF Aβ1-42 and CSF Aβ1-40 from all individual samples (total of 108 samples). Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.86*x + 15, r2 = 0.97, P < 0.0001. Error bars indicate standard error. The significance of treatment effects was analyzed by analysis of variance (Supplemental Table 4).

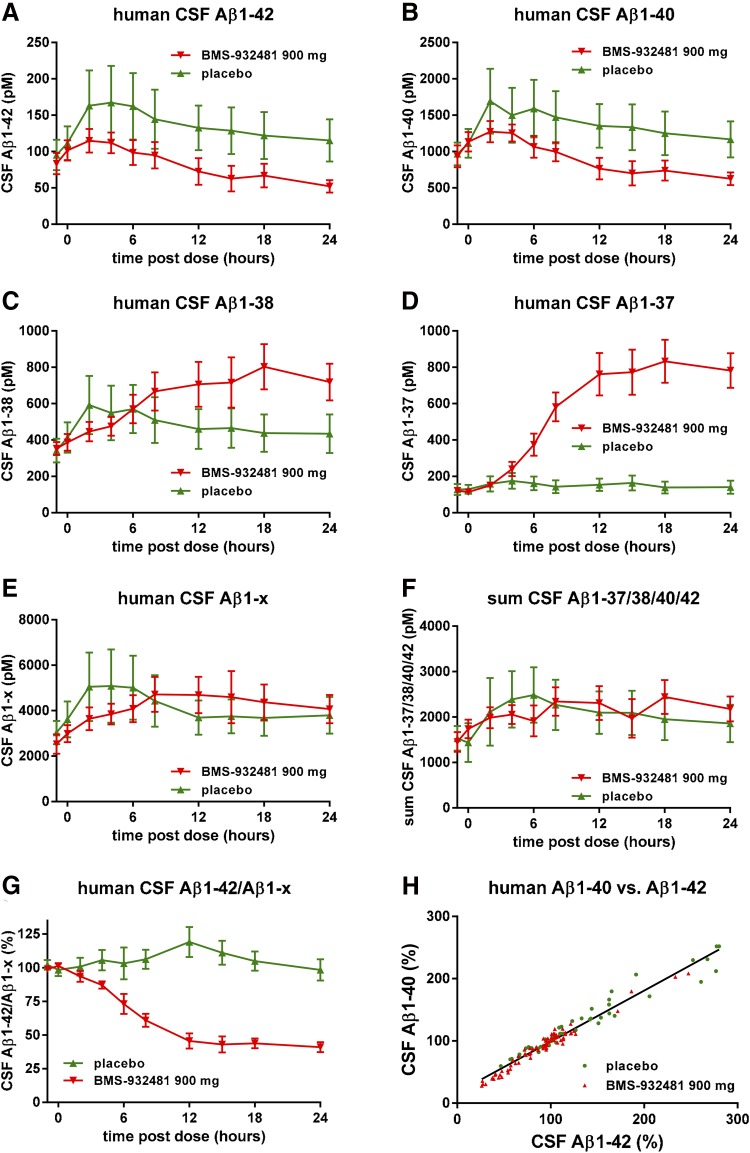

γ-Secretase Modulation of CSF Aβ Peptides in Human Subjects.

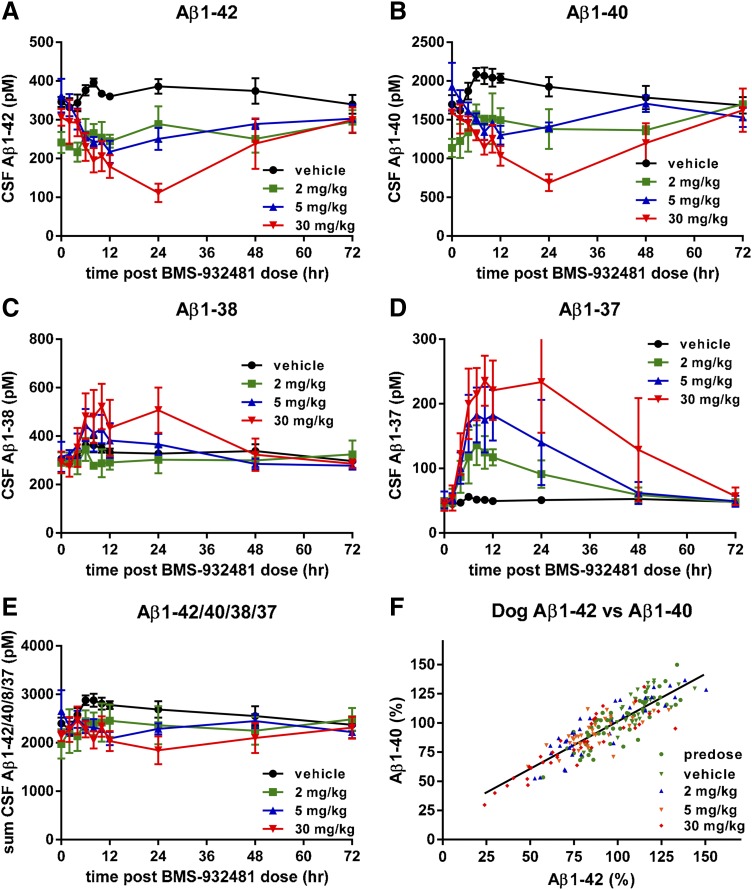

As part of a single ascending dose study, healthy human subjects were given a single 900-mg oral dose of BMS-932481, or placebo, and CSF was collected via indwelling lumbar catheter at a series of time points up to 24 hours after dosing. Additional details of the clinical program are described in the accompanying manuscript by Soares et al. (2016). Aβ1-42 in the BMS-932481 group gradually decreased to 50% of predose levels after 24 hours, whereas in the placebo group, there was a transient increase of ca. 60% (Fig. 6A). Likewise, Aβ1-40 showed a decrease in the BMS-932481 group and a transient increase in the placebo group (Fig. 6B). Aβ1-38 showed a gradual increase of about 2-fold in the BMS-932481 group and a transient increase in the placebo group (Fig. 6C). In contrast, Aβ1-37 showed a ca. 12-fold increase in the BMS-932481 group, and no significant change in the placebo group (Fig. 6D). Aβ1-x transiently increased by approximately 40% in both the BMS-932481 and placebo groups (Fig. 6E), as did the sum of the four peptides Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 (Fig. 6F). The increased CSF Aβ levels in the placebo groups are thought to be an artifact associated with frequent sampling of CSF via indwelling catheter (Bateman et al., 2007; May et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012a). The effect of this transient artifact can be effectively removed from the analysis by expressing Aβ1-42 levels relative to Aβ1-x levels, thereby emphasizing the biochemical effect on Aβ1-42 specifically due to BMS-932481 treatment (Fig. 6G). The time-dependent changes in CSF Aβ levels in individual human subjects for each of the four Aβ peptides are further illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 7. When normalized relative to predose levels of each peptide, as well as to Aβ1-x, the Aβ1-42/Aβ1-x and Aβ1-40/Aβ1-x ratios showed no overlap between BMS-932481 and placebo from 12 hours onward (Supplemental Fig. 7, A and B). The Aβ1-37/Aβ1-x ratio showed the greatest degree of separation between BMS-932481 and placebo, with complete separation of the groups after 6 hours (Supplemental Fig. 7C). For Aβ1-38, the separation between BMS-932481 and placebo was less pronounced (Supplemental Fig. 7D). The concentration of BMS-932481 in human blood plasma after the 900-mg dose is illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 7E.

Fig. 6.

Altered levels of CSF Aβ peptides in human subjects given a single oral dose of BMS-932481. Healthy human subjects were given a single 900-mg oral dose of BMS-932481 (n = 10) or placebo (n = 5), and CSF samples were taken through an implanted lumbar catheter at intervals up to 24 hours. CSF Aβ1-42 (A), CSF Aβ1-40 (B), CSF Aβ1-38 (C), CSF Aβ1-37 (D), CSF Aβ1-x (E), and the sum of Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37 (F). (G) Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-x were calculated as a percentage relative to predose levels, then each Aβ1-42 value was divided by the corresponding Aβ1-x value. (H) Scatter plot for CSF Aβ1-42 and CSF Aβ1-40 from all individual samples (total of 108 samples). Linear regression showed a best fit of y = 0.81*x + 17, r2 = 0.96, P < 0.0001. Error bars indicate standard error. The significance of treatment effects was analyzed by analysis of variance (Supplemental Table 5).

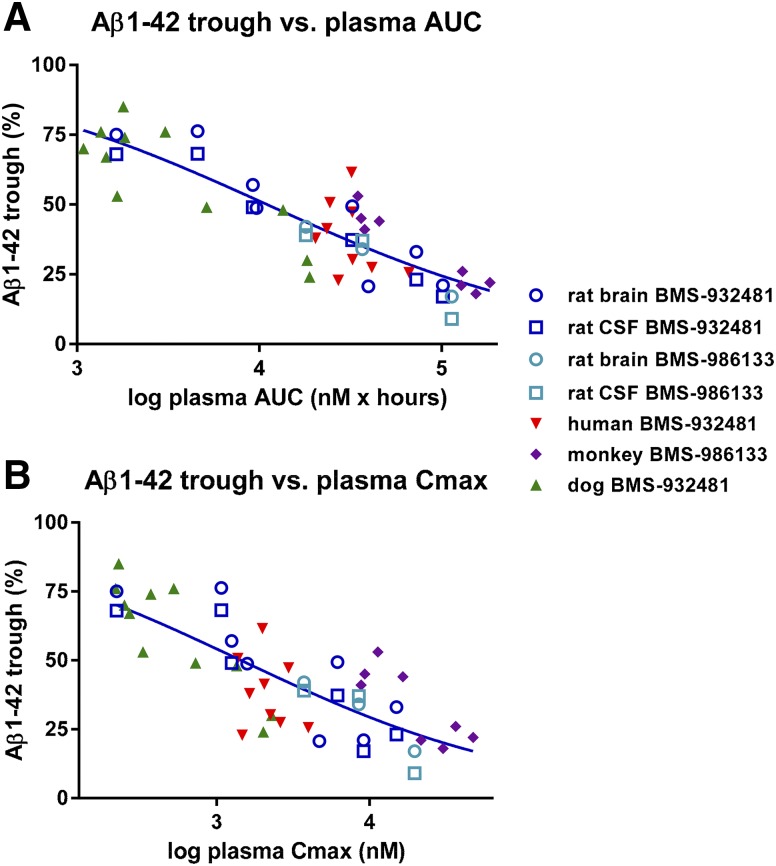

Pharmacological Comparison of γ-Secretase Modulation across Preclinical Species and Human Subjects.

To evaluate whether the PK/PD relationships were similar across preclinical species and human subjects, plasma exposure of BMS-932481 and Aβ1-42 lowering for rat, dog, monkey, and human were compared. For each dose in each experiment, the maximal lowering (trough) of Aβ1-42 was plotted against plasma AUC. This revealed a consistent relationship between plasma exposure and Aβ1-42 lowering (Fig. 7A). A variant of this approach was to plot the Aβ1-42 trough against plasma Cmax, which also showed a consistent trend among all four species (Fig. 7B). Additional plots utilizing Aβ1-42 ABEC instead of Aβ1-42 trough showed the same trends, but with increased scatter (not shown). The same conclusions about consistent PK/PD across all four species can be drawn with respect to Aβ1-40, because the effect of GSMs on Aβ1-40 lowering was highly correlated with Aβ1-42 lowering in all four species. Thus, the relationship of target engagement to peripheral exposure is consistent across species.

Fig. 7.

Alignment of BMS-932481 PK/PD across species. (A) Scatter plot of CSF Aβ1-42 trough versus plasma AUC: CSF Aβ1-42 trough (minimum level of Aβ1-42 after dosing) and plasma AUC were determined for each individual human subject, and for each dose in individual dogs and monkeys. For rats, Aβ1-42 trough for brain, Aβ1-42 trough for CSF, and plasma AUC were calculated using group means. Rat values were derived from the experiment illustrated in Fig. 2, Supplemental Figs. 3–5, and two additional time-course studies with BMS-932481 (not shown). Nonlinear fit of the entire data set indicates 50% inhibition at AUC = 11 μM⋅h. (B) Scatter plot of CSF Aβ1-42 trough versus plasma Cmax. Nonlinear fit indicates 50% inhibition at Cmax = 1.5 μM.

Lack of Notch-Related Effects and Observations on Human Safety.

As part of an initial safety assessment, rats were given daily oral doses of BMS-932481 at 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg for 14 days. On day 14, AUC exposures averaged 892 μM•h in male rats and 508 μM•h in female rats at the top dose. There were no histologic changes suggestive of Notch inhibition, including lymphoid depletion in splenic marginal zones, intestinal goblet cell metaplasia, and ovarian atrophy, at any dose level. Thus, even at exposures far above those required for robust changes in Aβ peptides (area under the concentration-time curve in the time interval between dosing and 24 hours exhibited exposures of 4.5, 32, and 71 μM•h; see Fig. 2H), there was no evidence of Notch-related side effects. On the other hand, during a multiple-dose study in healthy human subjects, two subjects at the 200-mg dose exhibited increases in serum liver function enzymes that resolved upon cessation of the drug (Soares et al., 2016). When compared with the doses and exposure of the drug required to reduce Aβ1-42 by an amount sufficient to constitute a valid test of the amyloid hypothesis (e.g., >25–50% reduction), the therapeutic index of BMS-932481 was considered to be insufficient to proceed safely with further clinical development of the molecule in patients.

Discussion

In this report, the potent novel GSMs, BMS-932481 and BMS-986133, were evaluated for their effects on the four main Aβ peptides: Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, Aβ1-38, and Aβ1-37. Pharmacological potency was found to be consistent across cell cultures, rat, dog, monkey, and human subjects. In all four species, CSF Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 were decreased, whereas CSF Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 showed corresponding increases that conserved the overall level of CSF Aβ peptides. Furthermore, the PK/PD relationship was consistent across all species, thus confirming the value of preclinical species for prediction of pharmacology in humans. Additional details of the clinical program for BMS-932481 are reported in an accompanying manuscript (Soares et al., 2016).

Potency and Activity.

The logic of analyzing the two GSMs, BMS-932481 and BMS-986133, together is based on their structural and pharmacological similarity. First, the two compounds have similar potencies for Aβ1-42 lowering in vitro, with IC50 values in the single-digit nanomolar range. Second, the PK/PD relationships of the two compounds proved to be essentially identical when compared head-to-head in the rat. Third, both compounds showed the same robust decreases in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40, accompanied by simultaneous increases in Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37, resulting in conservation of the overall levels of Aβ peptides. Fourth, the PK/PD for BMS-986133 in rats and monkeys was well aligned with the PK/PD of BMS-932481 in rats, dogs, and humans.

PK/PD in Brain versus CSF.

In rats treated with BMS-932481 and BMS-986133, decreases in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 and increases in Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 were observed within minutes of dosing, followed by a return toward baseline after 7–12 hours. The effects of dose and time were similar in brain and CSF, although maximum effects on the peptides occurred slightly earlier in CSF in the 7-hour sample (Supplemental Fig. S3 and S5) than in brain in the 12-hour sample (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. 4). Likewise, several studies, using either GSIs or GSMs, have shown greater and more rapid effects in CSF than in brain (Abramowski et al., 2008; Martone et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2011; Albright et al., 2013). The differences between brain and CSF Aβ time-course profiles have been ascribed to a greater rate of clearance (Kout) for CSF Aβ relative to brain Aβ, as well as to a limitation in the maximal extent of brain Aβ lowering (Imax) relative to CSF Aβ (Lu et al., 2011; Tai et al., 2012). Notably, the differences in pharmacological parameters were independent of the mechanism of Aβ lowering, being similar for GSMs, GSIs, and β-APP cleaving enzyme inhibitors (Lu et al., 2012). However, in our rat studies, the differences between brain and CSF pharmacodynamics appeared less pronounced, consistent with several previous studies (Barten et al., 2005; Best et al., 2005, 2006; Lanz et al., 2010).

Significant correlations were found between Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 peptides in CSF and brain of individual rats treated with BMS-932481 or BMS-986133 (Fig. 3, C and D), consistent with previous reports using GSIs (Shapiro et al., 2012; Tai et al., 2012). However, the baseline levels of brain and CSF Aβ1-42 in vehicle-treated rats showed little evidence of correlation. Therefore, to evaluate the effect of GSMs independently of the individual rat Aβ variation, the effect on the overall time course was taken into account. Thus, the ABEC was calculated for each dose. The percentage decrease in ABEC was found to be nearly identical between brain and CSF for Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40. Likewise, the increases in Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 ABEC also showed a linear relationship, but the increase in ABEC was about 1.4-fold greater in CSF than in brain. Thus, the pharmacodynamic effects were closely equivalent between brain and CSF, confirming the potential of CSF Aβ peptides as pharmacodynamic biomarkers for brain Aβ peptides in the clinic.

Aβ Placebo Rise.

A complicating factor was the Aβ placebo rise, which is a transient increase in CSF Aβ levels known to occur during frequent sampling via lumbar catheter in human subjects (Bateman et al., 2007; May et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012). The Aβ placebo rise is independent of drug treatment, and was observed in CSF cannulated dogs and monkeys, as well as in human subjects (Figs. 4–6). It was not observed in rats because only terminal CSF samples were taken. The rise was most pronounced for Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, and Aβ1-38, but absent for Aβ1-37, perhaps suggesting an analytical recovery artifact associated with the more hydrophobic peptides. Although there is still no clear explanation for the placebo rise, it is clearly not related to drug treatment.

Translation across Species.

The GSMs exhibited similar PK/PD in rats, dogs, monkeys, and humans. In particular, the Aβ1-42 trough (lowest level of Aβ1-42 observed after dosing) at each dose was closely related to the plasma AUC exposure across all preclinical species and human subjects (Fig. 7). The same conclusion can be drawn for Aβ1-40, because the GSMs caused closely correlated decreases in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 peptides in all species. The decrease in Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 was balanced by corresponding increases in Aβ1-38 and Aβ1-37 production, such that the total combined level of the four peptides remained constant in all species. Likewise, the Aβ1-x ELISA assay, which detects all four peptides, showed no significant changes upon GSM treatment in all species.

One consequence of the noninhibitory mechanism and conservation of Aβ levels is that the proportion of Aβ1-42 goes down in the presence of GSMs. For example, Aβ1-42 lowering by 50% would decrease the ratio of Aβ1-42 relative to the total Aβ peptide levels by 50%. Increased levels of the shorter Aβ peptides inhibit Aβ1-42 aggregation (Watanabe et al., 2006; Murray et al., 2009) and thereby attenuate its neurotoxic properties (Kuperstein et al., 2010). This is opposite to the effect of presenilin FAD mutants, which increase the relative proportion of Aβ1-42, and are associated with earlier AD age of onset (Duering et al., 2005; Kumar-Singh et al., 2006). Thus, GSMs are attractive not only because they lower the proportion of the disease-associated Aβ1-42 peptide, but also because they affect Aβ peptides in a direction opposed to that of presenilin FAD mutations.

Off Targets.

In cellular and animal studies, BMS-932481 did not appear to effect the proteolytic processing of Notch at concentrations or exposures that resulted in maximal modulation of Aβ peptides. Despite achieving plasma exposures in human subjects in the range that inhibited Notch processing in the in vitro assay, no adverse effects generally believed to be attributable to inhibition of Notch processing were observed clinically (e.g., untoward gastrointestinal effects or skin abnormalities). This is likely due to the high degree of nonspecific plasma protein binding exhibited by the compound (>90%), rendering the free plasma concentration significantly less than both the reported total plasma concentration and the potency in the in vitro Notch assay (performed in the absence of serum). The lack of effect of BMS-932481 on Notch processing is consistent with the mechanism of GSMs and is anticipated to be a significant advantage over enzymatic inhibitors of γ-secretase. On the other hand, BMS-932481 produced increases in plasma concentrations of liver function enzymes in multiple-day dosing studies, which is generally interpreted as a sign of hepatic inflammation or damage. These changes were transient in that the plasma concentration of these markers resolved following discontinuation of the administration of BMS-932481. Because this effect on safety precluded robust Aβ lowering by oral dosing, further clinical development of the molecule was terminated. The mechanism underlying the observed increases in hepatic enzymes is unclear, although it is unlikely to be mechanism-based. Due to the high degree of nonspecific protein binding and lipophilicity of BMS-932481, the plasma exposures that were required to achieve significant modulation of γ-secretase in brain were relatively high for a therapeutic intended to be administered chronically, i.e., in the micromolar range. In addition, in preliminary experiments (data not shown), we found that molecules structurally related to BMS-932481 exhibited accumulation in the liver following single and multiple doses in rats. Thus, the observed changes in plasma concentrations in hepatic enzymes are likely due to the high level of xenobiotic load and accumulation in the liver at exposures required for a desirable range of modulation of γ-secretase.

In conclusion, these studies demonstrate proof of the GSM mechanism in normal human subjects and illustrate the utility of building comprehensive PK/PD data sets in preclinical species to make predictions of pharmacological activity in human subjects. A remaining challenge is to predict non–mechanism-related or off-target safety effects to identify safe compounds for clinical studies. Nevertheless, these studies suggest that the GSM mechanism has therapeutic potential, and that GSMs with improved clinical safety profiles should be tested in AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank many additional colleagues who contributed to this work: Joerg Deerberg and Ravi Tejwani for scaleup and supplies of active pharmaceutical ingredient; Ping Chen, Sharon Aborn, Keely Hintz, Greg Hirshfeld, Heidi Dulac, Nestor Barrezueta, Maria Pierdomenico, Greg Cadelina, Alan Lin, Ling Yang, Craig Polson, and Yili Yang for the in-life work in animals; Rudy Krause for automated Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 assays; and Dr. Pankaj Mehta, New York University School of Medicine, for rabbit polyclonal Aβ1-37–selective antibodies.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid-β peptide

- ABEC

area between the Aβ vehicle-dosed baseline and the Aβ effect curve

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

amyloid-β precursor protein

- AUC

area under the concentration-time curve

- BMS-299897

(R)-4-(2-(1-((4-chloro-N-(2,5-difluorophenyl)phenyl)sulfonamido)ethyl)-5-fluorophenyl)butanoic acid

- BMS-698861

(R)-2-((4-chloro-N-(2-fluoro-4-(1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)benzyl)phenyl)sulfonamido)-3-cyclopropylpropanamide

- BMS-932481

(S)-7-(4-fluorophenyl)-N2-(3-methoxy-4-(3-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)-N4-methyl-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine

- BMS-986133

(S,Z)-17-(4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-34-(3-methyl-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-16,17-dihydro-15H-4-oxa-2,9-diaza-1(2,4)-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidina-3(1,3)-benzenacyclononaphan-6-ene

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FAD

familial AD

- GSI

γ-secretase inhibitor

- GSM

γ-secretase modulator

- MS-MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PK/PD

pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Toyn, Boy, Raybon, Meredith, Denton, Thompson, Lentz, Padmanabha, Drexler, Macor, Albright, Gasior, Olson, Soares, AbuTarif, Ahlijanian.

Conducted experiments: Robertson, Guss, Hoque, Sweeney, Clarke, Snow, Morrison, Berisha, Cook, Furlong, Wei.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Boy, Zhuo, Zuev.

Performed data analysis: Toyn, Raybon, Denton, Grace, Wang, Hong.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Toyn, Ahlijanian.

Footnotes

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Abramowski D, Wiederhold K-H, Furrer U, Jaton AL, Neuenschwander A, Runser MJ, Danner S, Reichwald J, Ammaturo D, Staab D, et al. (2008) Dynamics of Abeta turnover and deposition in different β-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models following γ-secretase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 327:411–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright CF, Dockens RC, Meredith JE, Jr, Olson RE, Slemmon R, Lentz KA, Wang JS, Denton RR, Pilcher G, Rhyne PW, et al. (2013) Pharmacodynamics of selective inhibition of γ-secretase by avagacestat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 344:686–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barten DM, Guss VL, Corsa JA, Loo A, Hansel SB, Zheng M, Munoz B, Srinivasan K, Wang B, Robertson BJ, et al. (2005) Dynamics of β-amyloid reductions in brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and plasma of β-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice treated with a γ-secretase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312:635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RJ, Wen G, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. (2007) Fluctuations of CSF amyloid-β levels: implications for a diagnostic and therapeutic biomarker. Neurology 68:666–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JD, Jay MT, Otu F, Churcher I, Reilly M, Morentin-Gutierrez P, Pattison C, Harrison T, Shearman MS, Atack JR. (2006) In vivo characterization of Abeta(40) changes in brain and cerebrospinal fluid using the novel γ-secretase inhibitor N-[cis-4-[(4-chlorophenyl)sulfonyl]-4-(2,5-difluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]-1,1,1-trifluoromethanesulfonamide (MRK-560) in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 317:786–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JD, Jay MT, Otu F, Ma J, Nadin A, Ellis S, Lewis HD, Pattison C, Reilly M, Harrison T, et al. (2005) Quantitative measurement of changes in amyloid-β(40) in the rat brain and cerebrospinal fluid following treatment with the γ-secretase inhibitor LY-411575 [N2-[(2S)-2-(3,5-difluorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethanoyl]-N1-[(7S)-5-methyl-6-oxo-6,7-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,d]azepin-7-yl]-L-alaninamide]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313:902–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgegard T, Juréus A, Olsson F, Rosqvist S, Sabirsh A, Rotticci D, Paulsen K, Klintenberg R, Yan H, Waldman M, et al. (2012) First and second generation γ-secretase modulators (GSMs) modulate amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide production through different mechanisms. J Biol Chem 287:11810–11819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy KM, Guernon JM, Macor JE, Thompson LA III, Wu Y-J, Zhang Y. (2014a) Compounds for the Reduction of Beta-Amyloid Production. US 8637523. Assignee: Bristol-Myers Squibb. [Google Scholar]

- Boy KM, Guernon JM, Macor JE, Olson RE, Shi J, Thompson LA III, Wu Y-J, Xu L, Zhang Y, Zuev DS. (2014b) Compounds for the Reduction of Beta Amyloid Production. US 8637525 B2. Assignee: Bristol-Myers Squibb. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JP, Bennett CE, McCracken TM, Mazzola RD, Bara T, Buevich A, Burnett DA, Chu I, Cohen-Williams M, Josein H, et al. (2010) Iminoheterocycles as γ-secretase modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20:5380–5384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump CJ, Fish BA, Castro SV, Chau DM, Gertsik N, Ahn K, Stiff C, Pozdnyakov N, Bales KR, Johnson DS, et al. (2011) Piperidine acetic acid based γ-secretase modulators directly bind to Presenilin-1. ACS Chem Neurosci 2:705–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duering M, Grimm MOW, Grimm HS, Schröder J, Hartmann T. (2005) Mean age of onset in familial Alzheimer’s disease is determined by amyloid beta 42. Neurobiol Aging 26:785–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebke A, Luebbers T, Fukumori A, Shirotani K, Haass C, Baumann K, Steiner H. (2011) Novel γ-secretase enzyme modulators directly target presenilin protein. J Biol Chem 286:37181–37186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Smith TE, Weggen S, Das P, McLendon DC, Ozols VV, Jessing KW, Zavitz KH, Koo EH, et al. (2003) NSAIDs and enantiomers of flurbiprofen target γ-secretase and lower Abeta 42 in vivo. J Clin Invest 112:440–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findeis MA. (2007) The role of amyloid β peptide 42 in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Ther 116:266–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko DR, Graff-Radford N, May S, Hendrix S, Cottrell BA, Sagi SA, Mather G, Laughlin M, Zavitz KH, Swabb E, et al. (2007) Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and Abeta levels after short-term administration of R-flurbiprofen in healthy elderly individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21:292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman KW, Starrett JE, Jr, Parker MF, Xie K, Bronson JJ, Marcin LR, McElhone KE, Bergstrom CP, Mate RA, Williams R, et al. (2010) Discovery and evaluation of BMS-708163, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable γ-secretase inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett 1:120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapasalo A, Kovacs DM. (2011) The many substrates of presenilin/γ-secretase. J Alzheimers Dis 25:3–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297:353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J, Harrison DC, Ahmed S, Davis RP, Chapman T, Marshall I, Smith B, Mead TL, Medhurst A, Giblin GM, et al. (2011) Dynamics of Aβ42 reduction in plasma, CSF and brain of rats treated with the γ-secretase modulator, GSM-10h. Neurodegener Dis 8:455–464. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumpertz T, Rennhack A, Ness J, Baches S, Pietrzik CU, Bulic B, Weggen S. (2012) Presenilin is the molecular target of acidic γ-secretase modulators in living cells. PLoS One 7:e30484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran E. (2012) Current status of vaccination therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 123:647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B. (2011) The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10:698–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kounnas MZ, Danks AM, Cheng S, Tyree C, Ackerman E, Zhang X, Ahn K, Nguyen P, Comer D, Mao L, et al. (2010) Modulation of γ-secretase reduces β-amyloid deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 67:769–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukar T, Prescott S, Eriksen JL, Holloway V, Murphy MP, Koo EH, Golde TE, Nicolle MM. (2007) Chronic administration of R-flurbiprofen attenuates learning impairments in transgenic amyloid precursor protein mice. BMC Neurosci 8:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar-Singh S, Theuns J, Van Broeck B, Pirici D, Vennekens K, Corsmit E, Cruts M, Dermaut B, Wang R, Van Broeckhoven C. (2006) Mean age-of-onset of familial alzheimer disease caused by presenilin mutations correlates with both increased Abeta42 and decreased Abeta40. Hum Mutat 27:686–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperstein I, Broersen K, Benilova I, Rozenski J, Jonckheere W, Debulpaep M, Vandersteen A, Segers-Nolten I, Van Der Werf K, Subramaniam V, et al. (2010) Neurotoxicity of Alzheimer’s disease Aβ peptides is induced by small changes in the Aβ42 to Aβ40 ratio. EMBO J 29:3408–3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Fici GJ, Merchant KM. (2005) Lack of specific amyloid-β(1-42) suppression by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in young, plaque-free Tg2576 mice and in guinea pig neuronal cultures. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Wood KM, Richter KEG, Nolan CE, Becker SL, Pozdnyakov N, Martin BA, Du P, Oborski CE, Wood DE, et al. (2010) Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the γ-secretase inhibitor PF-3084014. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Llano DA, Ellis T, LeBlond D, Bhathena A, Jhee SS, Ereshefsky L, Lenz R, Waring JF. (2012a) Effect of human cerebrospinal fluid sampling frequency on amyloid-β levels. Alzheimers Dement 8:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Riddell D, Hajos-Korcsok E, Bales K, Wood KM, Nolan CE, Robshaw AE, Zhang L, Leung L, Becker SL, et al. (2012) Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β (Aβ) as an effect biomarker for brain Aβ lowering verified by quantitative preclinical analyses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 342:366–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhang L, Nolan CE, Becker SL, Atchison K, Robshaw AE, Pustilnik LR, Osgood SM, Miller EH, Stepan AF, et al. (2011) Quantitative pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analyses suggest that the 129/SVE mouse is a suitable preclinical pharmacology model for identifying small-molecule γ-secretase inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339:922–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martone RL, Zhou H, Atchison K, Comery T, Xu JZ, Huang X, Gong X, Jin M, Kreft A, Harrison B, et al. (2009) Begacestat (GSI-953): a novel, selective thiophene sulfonamide inhibitor of amyloid precursor protein γ-secretase for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331:598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PC, Dean RA, Lowe SL, Martenyi F, Sheehan SM, Boggs LN, Monk SA, Mathes BM, Mergott DJ, Watson BM, et al. (2011) Robust central reduction of amyloid-β in humans with an orally available, non-peptidic β-secretase inhibitor. J Neurosci 31:16507–16516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani Y, Akashiba H, Saita K, Yarimizu J, Uchino H, Okabe M, Asai M, Yamasaki S, Nozawa T, Ishikawa N, et al. (2014) Pharmacological characterization of the novel γ-secretase modulator AS2715348, a potential therapy for Alzheimer’s disease, in rodents and nonhuman primates. Neuropharmacology 79:412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani Y, Yarimizu J, Saita K, Uchino H, Akashiba H, Shitaka Y, Ni K, Matsuoka N. (2012) Differential effects between γ-secretase inhibitors and modulators on cognitive function in amyloid precursor protein-transgenic and nontransgenic mice. J Neurosci 32:2037–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MM, Bernstein SL, Nyugen V, Condron MM, Teplow DB, Bowers MT. (2009) Amyloid β protein: Abeta40 inhibits Abeta42 oligomerization. J Am Chem Soc 131:6316–6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano-Ito K, Fujikawa Y, Hihara T, Shinjo H, Kotani S, Suganuma A, Aoki T, Tsukidate K. (2014) E2012-induced cataract and its predictive biomarkers. Toxicol Sci 137:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki Y, Higo T, Uemura K, Shimada N, Osawa S, Berezovska O, Yokoshima S, Fukuyama T, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T. (2011) Phenylpiperidine-type γ-secretase modulators target the transmembrane domain 1 of presenilin 1. EMBO J 30:4815–4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okochi M, Tagami S, Yanagida K, Takami M, Kodama TS, Mori K, Nakayama T, Ihara Y, Takeda M. (2013) γ-secretase modulators and presenilin 1 mutants act differently on presenilin/γ-secretase function to cleave Aβ42 and Aβ43. Cell Reports 3:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozdnyakov N, Murrey HE, Crump CJ, Pettersson M, Ballard TE, Am Ende CW, Ahn K, Li YM, Bales KR, Johnson DS. (2013) γ-Secretase modulator (GSM) photoaffinity probes reveal distinct allosteric binding sites on presenilin. J Biol Chem 288:9710–9720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Bryce R, and Ferri C (2011) The benefits of early diagnosis and intervention. Alzheimer’s Disease International World Alzheimer Report 2011 pp 1-68, Alzheimer's Disease International, London.

- Shapiro JS, Stiteler M, Wu G, Price EA, Simon AJ, Sankaranarayanan S. (2012) Cisterna magna cannulated repeated CSF sampling rat model--effects of a gamma-secretase inhibitor on Aβ levels. J Neurosci Methods 205:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares HD, Gasior M, Toyn JH, Wang J-S, Hong Q, Berisha F, Furlong MT, Raybon J, Lentz KA, Sweeney F, et al. (2016) The gamma secretase modulator, BMS-932481, modulates Aβ peptides in the plasma and CSF of healthy volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther DOI: 10.1124/jpet.116.232256 [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai LM, Jacobsen H, Ozmen L, Flohr A, Jakob-Roetne R, Caruso A, Grimm HP. (2012) The dynamics of Aβ distribution after γ-secretase inhibitor treatment, as determined by experimental and modelling approaches in a wild type rat. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 39:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate B, McKee TD, Loureiro RMB, Dumin JA, Xia W, Pojasek K, Austin WF, Fuller NO, Hubbs JL, Shen R, et al. (2012) Modulation of gamma-secretase for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012:210756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyn JH, Ahlijanian MK. (2014) Interpreting Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials in light of the effects on amyloid-β. Alzheimers Res Ther 6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyn JH, Thompson LA, Lentz KA, Meredith JE, Jr, Burton CR, Sankaranararyanan S, Guss V, Hall T, Iben LG, Krause CM, et al. (2014) Identification and preclinical pharmacology of the γ-secretase modulator BMS-869780. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2014:431858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Z, Hall A, Jin Y, Xiang JN, Yang E, Eatherton A, Smith B, Yang G, Yu H, Wang J, et al. (2011a) Pyridazine-derived γ-secretase modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21:4016–4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Z, Hall A, Sang Y, Xiang JN, Yang E, Smith B, Harrison DC, Yang G, Yu H, Price HS, et al. (2011b) Pyridine-derived γ-secretase modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21:4832–4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Bernier F, and Miyakawa T (2006) A therapeutic agent for Aβ related disorders. International patent publication WO2006/112552. Assignee: Eisai Company Ltd., Tokyo.

- Weggen S, Eriksen JL, Das P, Sagi SA, Wang R, Pietrzik CU, Findlay KA, Smith TE, Murphy MP, Bulter T, et al. (2001) A subset of NSAIDs lower amyloidogenic Abeta42 independently of cyclooxygenase activity. Nature 414:212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A and Prince M (2010) The global economic impact of dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease International World Alzheimer Report 2010. pp 1-51, Alzheimer's Disease International, London.

- Yu Y, Logovinsky V, Schuck E, Kaplow J, Chang M-K, Miyagawa T, Wong N, Ferry J. (2014) Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the novel γ-secretase modulator, E2212, in healthy human subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 54:528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.