Abstract

Background

The clinical course of Dementia with Lewy Bodies patients is heterogeneous. The ability to more accurately prognosticate survival is important.

Objective

To investigate hippocampal volume as a predictor of survival in Dementia with Lewy Bodies patients.

Methods

Survival analysis for time from onset of cognitive symptoms to death was carried out using Cox proportional hazards models. Given their age and total intracranial volume, patients were dichotomized into low/medium (0–66.7%) and high (66. 7–100%) hippocampal volume categories. The models using these categories to predict survival were adjusted for field strength, APOE e4 status and estimated onset age of cognitive problems.

Results

We investigated 167 consecutive patients with Dementia with Lewy Bodies. The median age at MRI was 72 years (interquartile range: 67, 76), and 80% were male. The median time from estimated first cognitive symptom to death was 7.4 years (interquartile range: 5.7, 10.2). Lower hippocampal volumes were significantly associated with higher risk of death (Hazard ratio 1.28 (95% confidence interval (1.04–1.58), p=0.029). The predicted median survival for participants with onset of cognitive symptoms at age 68 was 10.63 years (95% confidence interval (8.66–14.54) for APOE e4 negative, high hippocampal volume participants, 8.89 years (7.56–12.36) for APOE e4 positive, high hippocampal volume participants, 8.10 years (7.34–11.08) for APOE e4 negative, low/medium hippocampal volume participants, and 7.38 (6.74–9.29) years for APOE e4 positive, low/medium hippocampal volume participants.

Conclusions

Among patients with clinically diagnosed Dementia with Lewy Bodies, those with neuroimaging evidence of hippocampal atrophy have shorter survival times.

Introduction

In general, the clinical course of Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) is more aggressive than Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia. DLB patients have a shorter survival compared to AD dementia patients1 and are admitted to nursing homes approximately 2 years earlier than AD dementia patients from the time of diagnosis2. In addition, DLB patients have a faster cognitive decline compared to AD dementia3. While the median survival after dementia onset in DLB is approximately seven years, there is significant variability in the clinical course. DLB is one of the most common causes of neurodegenerative rapidly progressive dementia4. The unpredictable course of DLB is frustrating for patients and caregivers who want an accurate prognosis. The ability to more accurately prognosticate survival on an individual level is important.

Similar to most neurodegenerative dementias5, DLB patients often have mixed pathology at autopsy6. Pathologic data suggests that DLB cases with significant coexisting AD have worse cognitive function than those with relatively pure DLB7. While smaller medial temporal lobe size on MRI distinguishes AD from DLB8, a substantial proportion of persons with DLB have medial temporal atrophy9. In DLB patients, preserved hippocampal volumes are associated with improved treatment response with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors10. Limited pathologic data suggests that AD pathology burden at autopsy is associated with a shorter survival in DLB patients11. In DLB patients, hippocampal volume is associated with Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary tangle pathology12. Therefore, our objective was to investigate whether hippocampal volumes can predict survival in patients with probable DLB.

Methods

Patients

Prospectively followed patients from the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s disease research center (ADRC) with an eventual diagnosis of clinically probable DLB underwent antemortem MRI between 1/1997 and 7/2015 (n=167). Since we used the baseline MRI scan, 37 (22%) participants were in the MCI stage of DLB at the time of the scan. All patients met published criteria13 for the diagnosis of probable DLB. All cases seen prior to the publication of the 3rd consortium consensus criteria were retrospectively verified to meet the clinical criteria of probable DLB. All patients had dementia (central feature), and either two or more core features (recurrent fully formed visual hallucinations, fluctuating cognition, parkinsonism) or one or more suggestive features (neuroleptic sensitivity, REM sleep behavior disorder) and one core feature. We did not use low dopamine transporter uptake as part of the criteria because it was not available for the majority of patients. Clinical and neuropsychological data were abstracted from the chart. Since all patients were enrolled in the ADRC, the estimated age of onset of cognitive symptoms was abstracted from the Uniform Data Set of the National Alzheimer’s Coordindating Centers. Patients with an event were defined by the date of their death. In any instances where the subjects did not die or where death was unknown, then these patients were censored at their last visit date, since this was the last known date of the patients being alive.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and informed consent for participation was obtained from every subject or an appropriate surrogate.

Neuropathologic assessment

54 patients in the study underwent autopsy. Sampling was done according to the CERAD protocol and the 3rd Report of the DLB Consortium.13, 14 NFTs and corresponding Braak stage were detected using thioflavin-S microscopy or Bielschowsky silver stain, and classified according to National Institutes of Aging–Reagan criteria.15 A polyclonal antibody to α-synuclein was used to categorize regional involvement of Lewy bodies as brainstem, limbic, and neocortical. The neuropathologic diagnosis of DLB was made according to the DLB Consortium criteria without consideration of clinical presentation.13

MRI acquisition

1.5 or 3 Tesla MRI scans (GE Healthcare) were performed for the automated segmentation of hippocampal volumes. With 1.5 Tesla, a 3-D high-resolution spoiled gradient recalled acquisition; was performed. At 3 Tesla, a 3-D high resolution magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) acquisition was performed.

The processing hippocampal volume data was performed using FreeSurfer version 5.3 and total intracranial volume was analyzed using statistical parametric mapping algorithm (SPM12). Hippocampal volumes at 1.5T were transformed to hippocampal volumes at 3T as previously described16. Field strength was 1.5T for 103 (62%) participants.

Statistical analysis

Our goal in these analyses was to assess the total effect of hippocampal volumes on survival, adjusting for non-mediating variables as necessary. We first fit linear regression models predicting hippocampal volumes (cm3) using age at MRI and TIV at MRI. The residuals from these models, basically measuring whether participants had relatively low or high values given their age and TIV, were subsequently used as predictors in the Cox proportional hazards models for survival from age at onset. We used the actual residuals, and residuals trichotomized at the 33rd and 67th percentiles into “low” (0%–33.33%), “medium” (33.33%–66.67%), and “high” (66.67%–100%) categories. We also looked at the simple coding of combined “low” and “medium” vs. “high” to facilitate comparisons. Cox proportional hazard models using the residual hippocampal volume values and categories to predict survival from age at onset were adjusted for scan type (1.5T or 3T), APOE4 and age of cognitive onset to account for design considerations (scan type) and likely population confounders. Using this method, we extracted hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and predicted survival times for participants with specific characteristics with onset of cognitive symptoms at different ages. We compared the quality of the models using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Since the analysis method was complicated by the two-stage linear regression and survival analysis, we used permutation tests (100,000 permutations) of the entire procedure, from linear regressions to final proportional hazard models, to produce final p-values. These p-values were very close to those from the asymptotic theory in the two-stage procedure.

Results

Participants

167 participants with DLB were included. Characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. Hippocampal volumes of the DLB patients compared to Alzheimer’s dementia subjects who have previously been used to generate AD biomarker cut-points are reported in the supplemental figure17. The Pearson correlation between age at onset and age at MRI was 0.95. Therefore, we did not have both age at onset and age at MRI in the same Cox proportional hazards model to prevent problems with multicollinearity. In addition, no co-linearity was observed between the residual hippocampal volumes and age at MRI (Pearson correlation of 0.0).

Table 1.

Characteristics of DLB participants at time of imaging

| n= 167 | |

| Males (%) | 134 (80) |

| ε4 carriers (%) | 79 (49) |

| Cognitive impairment onset age, years | 68 (63, 74) |

| MRI age, years | 72 (67, 76) |

| Education | 14 (12, 16) |

| DRS | 125 (112, 133) |

| MMSE | 24 (21, 27) |

| CDR sum of boxes | 3.0 (2.0, 5.0) |

| UPDRS | 8 (4, 13) |

| Time to death from cognitive impairment onset, years | 7.38 (5.72, 10.20) |

| Time to death/censor from MRI, years | 4.39 (2.13, 6.31) |

| Time to MRI from cognitive impairment onset, years | 3.16 (2.04, 4.60) |

| Events (%) | 120 (72) |

| Autopsies (%) | 54 (32) |

| MCI (%) | 37 (22) |

| Field strength 1.5T (%) | 103 (62) |

| AChEI treatment | 163 (98) |

Median (interquartile range) reported for the continuous variables and counts (%) for the categorical variables. AChEI = acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

Survival

In univariate analysis, age at onset (hazard ratio 1.06 ((95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03–1.08), p<.0001) and the presence of at least 1 APOE4 allele (hazard ratio 1.55 (95% CI 1.07–2.24), p=0.02) were associated with shorter survival. In other words, each additional year of age was associated with an estimated 6% increase in the risk of death, and patients with at least 1 APOE4 allele had an estimated risk of death 1.55 times that of patients without an APOE4 allele. Table 2 summarizes the survival data by hippocampal volume. DLB participants in the top 1/3 of hippocampal volumes (categorized as high hippocampal volumes) given their age and TIV survived longer. The AIC values for the models were all within 2 of each other, indicating that the models performed about equally well. These have been included in the supplemental table. Using the final model, for medium/low vs. high hippocampal volume, patients with medium/low volumes had an estimated risk of death 1.71 times that of patients with high volumes, holding the other covariates (scan type, age at onset, and APOE4) constant. APOE4 was not related to survival in any of the models when adjusting for residual hippocampal volume. The hazard ratio was 1.32 (95% CI 0.91–1.93) (permutation p value =0.148) in the first model (HV continuous) and the hazard ratio was 1.39 (0.95–2.02) (permutation p value =0.095) in the second model (all categories of hippocampal volume). In the final model, comparing medium/low hippocampal volume to high hippocampal volume, APOE4 status again was not associated with survival; the hazard ratio was 1.41 (95% CI 0.97–2.04) (permutation p-value 0.075). Analyses, additionally adjusting for Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), UPDRS, Dementia rating scale (DRS), MMSE, or frequency of hallucinations, indicated that our findings when comparing low/medium to high hippocampal volumes did not change after adjusting for CDR (p=0.035), UPDRS (p= 0.010), DRS (p=0.028), MMSE (p=0.044) and frequency of hallucinations (p=0.040).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios and p-values for hippocampal volume, combined scans

| Hippocampal Volume (cm3) | HR (95% CI) | Permutation test p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Low to High (continuous) | 1.28 (1.04–1.58) | 0.024 |

| Medium vs. High | 1.62 (1.02–2.58) | 0.048 |

| Low vs. High | 1.79 (1.14–2.83) | 0.013 |

| Medium/Low vs. High | 1.71 (1.14–2.55) | 0.010 |

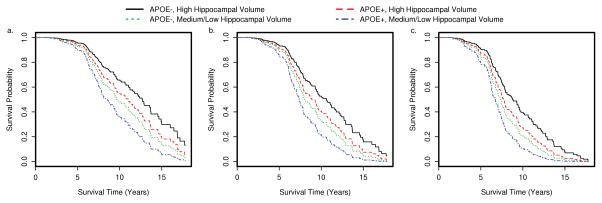

We extracted predicted survival for participants with specific characteristics. For example, the plots in Figure 1 describe predicted survival for participants with onset of cognitive symptoms at different ages. We also estimated median survival times for the same participants (Table 3). We included APOE4 in the predicted survival curves because there was a trend towards shorter survival with APOE e4.

Figure 1.

Predicted survival time by APOE4 status and hippocampal volume status for onset of cognitive symptoms at different ages a. age 60 b. age 68 c. age 75

Table 3.

Predicted median (95% confidence interval) survival times for participants with onset of cognitive symptoms at age 60, 68, and 75.

| Group | Age at onset 60 | Age at onset 68 | Age at onset 75 |

|---|---|---|---|

| APOE4−, High hippocampal volume | 12.68 (10.63–17.70) | 10.63 (8.66–14.54) | 8.77 (7.48–12.71) |

| APOE4+, High hippocampal volume | 11.04 (8.77–15.00) | 8.89 (7.56–12.36) | 7.74 (6.82–10.76) |

| APOE4−, Medium/Low hippocampal volume | 9.65 (8.10–13.70) | 8.10 (7.34–11.08) | 7.34 (6.52–9.45) |

| APOE4+, Medium/Low hippocampal volume | 8.56 (7.44–11.70) | 7.38 (6.74–9.29) | 6.74 (6.21–7.84) |

Neuropathologic confirmation

Among the 54 (32%) DLB patients who had autopsies, 34 (63%) were diagnosed with high likelihood DLB at autopsy, 15 (28%) were diagnosed with intermediate likelihood DLB, one (2%) was diagnosed with low likelihood DLB, one had amygdala only DLB (2%). Three cases (5%) had no Lewy body pathology. Twenty one were Braak neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) stage (0-II), seventeen were Braak NFT stage (III,IV), and sixteen were Braak NFT stage (V,VI). Eight patients had transitional Lewy Body pathology, forty one had diffuse lewy body pathology, one had brainstem predominant lewy body pathology, one had amygdala only lewy body pathology and three had no lewy body pathology. All three clinically diagnosed DLB cases without Lewy body pathology had AD pathology at autopsy; with two having Braak stage 6 and one having Braak stage 5 neurofibrillary tangle pathology. One case had amydgala only Lewy body pathology and was Braak tangle stage 5. One patient with AD had predominant posterior cortical tangle pathology (the pathologic substrate of posterior cortical atrophy) consistent with an atypical AD. One patient with high likelihood DLB had coexisting hippocampal sclerosis. There was no difference in hippocampal volumes between the autopsy confirmed group and the rest of the DLB group (p=0.68).

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that DLB patients with larger hippocampal volumes survived longer compared to those with lower hippocampal volumes. Further, the presence of an APOE4 allele was also associated with shorter survival, but after including residual hippocampal volume in the model, this association was no longer significant. In DLB with onset of symptoms at age 60, the combination of low hippocampal volume and the presence of APOE4 allele were associated with approximately a 4 year shorter predicted survival than the combination of preserved hippocampal volume and absence of APOE4 allele.

In DLB patients, hippocampal atrophy is associated with AD neurofibrillary tangle pathology12. Therefore, our findings are similar to the results of an autopsy based study which showed that among twelve dementia patients with pathologically confirmed DLB, the burden of AD pathology was associated with shorter survival11. Patients with mixed AD and DLB pathology have faster global brain atrophy and ventricular enlargement compared to those with DLB pathology18 who have atrophy rates similar to healthy controls19. Additionally, among DLB patients the absence of neuroimaging features of coexisting AD pathology (positive amyloid PET, hippocampal atrophy) is associated with treatment response to cholinesterase inhibitors10. Autopsy data indicates that there is a relative preservation of MMSE in DLB compared to mixed DLB/AD7. Therefore, DLB who have multiple pathologies appear to have a more malignant profile characterized by worse cognition, faster atrophy, poorer response to treatment, and shorter survival.

Neurologists are often asked to predict the clinical course and disease duration during clinical visits. Previous work suggests the average survival of DLB patients is approximately 7 years from diagnosis with the presence of parkinsonism and an APOE4 allele associated with shorter survival1. In this study, we individualized prognostication by taking into account hippocampal atrophy and APOE4 status. Although APOE4 status was no longer associated with survival when controlling for hippocampal volume, our power to detect a small effect was limited, and the hazard ratio of 1.41 (0.97–2.04) for APOE4 status when taking into account hippocampal volumes suggests that larger studies may be needed to detect this effect. Interestingly, recent evidence raises the possibility that APOE4 is associated with the development of DLB independent of AD pathology20.

Hippocampal volume and parkinsonism are likely not the only factors that influence survival in DLB 1. Additional factors likely play a role in the cases that present with rapidly progressive dementia, as a minority of DLB patients with rapidly progressive dementia may have no other coexisting pathology21. For example, one series found that these rapidly progressive DLB patients had a prior history of delirium with a surgery years prior to presentation4.

The strength of this study is the large number of longitudinally followed DLB patients. Autopsy data was available for approximately one third of the cohort suggesting a high accuracy for clinical diagnosis with 91% of DLB patients having intermediate to high likelihood DLB and 9% with low likelihood DLB or AD pathology. However, we acknowledge several limitations. The MRI scans were performed during the first research visit, which may be at different time points during each patient’s clinical course. We found a strong correlation (r=0.90) between the estimated cognitive symptom onset to death and MRI to death intervals, which suggest that such variations in each patient’s MRI scanning may not have significantly influenced our findings.

Approximately, 50–80% of DLB patients have evidence of 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) binding22–25. At autopsy, 81% of DLB cases are Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage III or higher6. If survival, treatment response, and cognitive impairment are influenced by coexisting AD pathology, then a subset of DLB patients may be candidates for therapeutic trials targeting AD pathology.

Conclusion

Among patients with clinically diagnosed DLB, those with neuroimaging evidence of hippocampal atrophy have shorter survival. Pathologic studies are needed to confirm these findings. If coexisting AD pathology can be confirmed to worsen survival in DLB patients, then a subset of DLB patients may benefit from therapeutics targeted at AD.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure. Boxplot of Hippocampal volume (HVa) showing 75 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients versus DLB patients split into tertiles; low, medium and high

Acknowledgments

Funding: Study Funding: NIH [K23 AG030935, R01 AG040042, R01 AG11378, P50 AG16574, U01 AG06786, C06 RR018898], Mangurian Foundation, the Elsie and Marvin Dekelboum Family Foundation, and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer s Disease Research Program

Footnotes

Authors’ Roles

-

Research project:

- Conception, Graff-Radford, Lesnick, and Kantarci

- Organization, All authors

- Execution; All authors

-

Statistical Analysis:

- Design, Graff-Radford, Lesnick, Przybelski and Kantarci

- Execution, Graff-Radford, Lesnick, Przybelski

- Review and Critique; All authors

-

Manuscript Preparation:

- Writing of the first draft, Graff-Radford, Lesnick

- Review and Critique, All authors

Study supervision, Petersen, Kantarci, Jack, Ferman, and Knopman.

Obtained funding: Petersen, Kantarci, Jack.

Financial Disclosures of all authors

Dr. Graff-Radford, Dr. Jones, Mr. Lesnick, Mr. Przybelski, Dr. Murray, Dr. Sarro report no disclosures.

Dr. Boeve receives royalties from the publication of Behavioral Neurology of Dementia and receives research support from Cephalon Inc, Allon Therapeutics, Forum Pharmaceuticals and GE Healthcare. He receives research support from the National Institute on Aging (P50 AG016574, U01 AG006786, RO1 AG032306, RO1 AG041797 and the Mangurian Foundation.

Dr. Ferman is funded by the NIH [Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center/Project 1-P50-AG16574/P1 [Co-I]).

Dr. Dickson receives research support from P50AG016574 (Core Leader); P50NS072187 (Center Director); P01NS084974 (Project Leader); P01AG003949 (Core Leader)

Dr. Knopman serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology®; serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the DIAN study; is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by TauRX Pharmaceuticals, Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study; and receives research support from the NIH.

Dr. Jack serves as a consultant for Eli Lily and receives research support from the NIA (RO1 AG11378 and RO1 AG041851), and the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Foundation.

Dr. Petersen serves on data monitoring committees data monitoring committee for Pfizer Inc and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy; working as a consultant for Merck Inc, Roche Inc, Biogen Inc, Eli Lily and Company, and Genentech Inc; and receives publishing royalties for Mild Cognitive Impairment (Oxford University Press, 2003) and receives research support from the NIH (P50-AG16574 [PI] and U01-AG06786 [PI], R01-AG11378 [Co-I], and U01–24904 [Co-I]).

Dr. Kantarci serves on the data safety monitoring board for Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc., data monitoring boards of Pfizer and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy; and she is funded by the NIH [R01AG040042 (PI), R21 NS066147 (PI), P50 AG44170/Project 2 (PI), P50 AG16574/Project 1 (PI), and R01 AG11378 (Co-I)

References

- 1.Williams MM, Xiong C, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1935–1941. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247041.63081.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rongve A, Vossius C, Nore S, Testad I, Aarsland D. Time until nursing home admission in people with mild dementia: comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:392–398. doi: 10.1002/gps.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olichney JM, Galasko D, Salmon DP, et al. Cognitive decline is faster in Lewy body variant than in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:351–357. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, et al. Rapidly progressive neurodegenerative dementias. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:201–207. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujishiro H, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, et al. Validation of the neuropathologic criteria of the third consortium for dementia with Lewy bodies for prospectively diagnosed cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:649–656. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817d7a1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, et al. Relative preservation of MMSE scores in autopsy-proven dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2009;73:1127–1133. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton EJ, Barber R, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, et al. Medial temporal lobe atrophy on MRI differentiates Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies and vascular cognitive impairment: a prospective study with pathological verification of diagnosis. Brain. 2009;132:195–203. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barber R, Gholkar A, Scheltens P, Ballard C, McKeith IG, O’Brien JT. Medial temporal lobe atrophy on MRI in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 1999;52:1153–1158. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graff-Radford J, Boeve BF, Pedraza O, et al. Imaging and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor response in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2012;135:2470–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakisaka Y, Furuta A, Tanizaki Y, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, Iwaki T. Age-associated prevalence and risk factors of Lewy body pathology in a general population: the Hisayama study. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;106:374–382. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantarci K, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, et al. Focal atrophy on MRI and neuropathologic classification of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2012;79:553–560. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826357a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newell KL, Hyman BT, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET. Application of the National Institute on Aging (NIA)-Reagan Institute criteria for the neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:1147–1155. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raman MR, Preboske GM, Przybelski SA, et al. Antemortem MRI findings associated with microinfarcts at autopsy. Neurology. 2014;82:1951–1958. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:765–775. doi: 10.1002/ana.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitwell JL, Jack CR, Jr, Parisi JE, et al. Rates of cerebral atrophy differ in different degenerative pathologies. Brain. 2007;130:1148–1158. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak E, Su L, Williams GB, et al. Longitudinal assessment of global and regional atrophy rates in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;7:456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuang D, Leverenz JB, Lopez OL, et al. APOE epsilon4 increases risk for dementia in pure synucleinopathies. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:223–228. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momjian-Mayor I, Pizzolato GP, Burkhardt K, Landis T, Coeytaux A, Burkhard PR. Fulminant Lewy body disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1748–1751. doi: 10.1002/mds.21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edison P, Rowe CC, Rinne JO, et al. Amyloid load in Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia measured with [11C]PIB positron emission tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1331–1338. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.127878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomperts SN, Rentz DM, Moran E, et al. Imaging amyloid deposition in Lewy body diseases. Neurology. 2008;71:903–910. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326146.60732.d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, et al. Multimodality imaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:2091–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maetzler W, Liepelt I, Reimold M, et al. Cortical PIB binding in Lewy body disease is associated with Alzheimer-like characteristics. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure. Boxplot of Hippocampal volume (HVa) showing 75 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients versus DLB patients split into tertiles; low, medium and high