Abstract

Estrogen measurements play an important role in the clinical evaluation of many endocrine disorders as well as in research on the role of hormones in human biology and disease. It remains an analytical challenge to quantify estrogens and their metabolites in specimens from special populations including older men, children, postmenopausal women and women receiving aromatase inhibitors. Historically, immunoassays have been used for measuring estrogens and their metabolites in biological samples for risk assessment. However, the lack of specificity and accuracy of immunoassay-based methods has caused significant problems when interpreting data generated from epidemiological studies and across different laboratories. Stable isotope dilution (SID) methodology coupled with liquid chromatography-selected reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (LC-SRM/MS) is now accepted as the ‘gold-standard’ to quantify estrogens and their metabolites in serum and plasma due to improved specificity, high accuracy, and the ability to monitor multiple estrogens when compared with immunoassays. Ultra-high sensitivity can be obtained with pre-ionized derivatives when using triple quadruple mass spectrometers in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode coupled with nanoflow LC. In this review, we have examined the special issues related to utilizing ultra-high sensitivity SID LC-SRM/MS-based methodology to accurately quantify estrogens and their metabolites in the serum and plasma from populations with low estrogen levels. The major issues that are discussed include: sample preparation for both unconjugated and conjugated estrogens, derivatization, chromatographic separation, matrix effects, and assay validation.

Keywords: Estrogens and their metabolites, Older men, Children, Postmenopausal women, Liquid chromatograph-tandem mass spectrometry, Stable isotope dilution methodology, Derivatization

Graphical Abstract

Estrogen measurement, one subset of steroid analysis, plays an important role in the clinical evaluation of many endocrine disorders as well as in research on the role of hormones in human biology and disease [1, 2]. For almost 30 years the predominant methodologies used to quantify circulating levels of estrogens were conventional radioimmunoassays (RIAs) or direct enzyme immunoassays [3–5]. These assays afford good sensitivity, but often lack specificity due to the cross-reaction of the antibodies used in the assays with other steroids. The inter-laboratory variability of immunoassays has caused significant problems when interpreting epidemiologic studies [4, 6]. Another limitation of immunoassay-based methods is the reliance on single analyte-by-analyte measurement, thus multiple assays are required to measure all the metabolites from a single estrogen [7]. Over the last decade, significant advances in stable isotope dilution (SID) methodology coupled with liquid chromatography-selected reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (LC-SRM/MS) have been made that can potentially offer a solution to these problems [4–9]. However, it is still challenging to quantify estrogens and their metabolites where ultra-high sensitivity is required, such as serum from older men [10], children [11–13], postmenopausal women and women receiving aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer treatment [4, 6]. The present review is focused on the issues and considerations when ultra-high sensitivity estrogen analysis is employed in serum and plasma. Some suggested practices for sample preparation, analyte derivatization, chromatographic separation, minimization of matrix effects, and assay validation for optimal use of SID LC-SRM/MS-based methodology have been discussed.

1. Estrogen metabolism

Several clinical and experimental studies showed that relatively high estrogen levels in the serum or plasma in women were associated with increased breast cancer risk [4, 6, 14, 15], endometrial cancer [16, 17], and ovarian cancer [18] although notably, these studies used RIA assays of questionable validity [5]. Increased circulating estrogens are also a potential risk factor for prostate cancer in men [10, 19]. In addition, diagnosis and treatment of disorders of puberty and sexual development have demonstrated the critical nature of quantitation of the levels of estradiol (E2) and testosterone (T) present in children [11, 12]. Some studies also showed that higher levels of estrogens at earlier ages are correlated with the onset of breast development in girls, suggesting that hormones during development might modulate disease risk later in life [20].

Estrogens are thought to act through either estrogen receptor (ER)-dependent or ER-independent mechanisms [21, 22]. The mechanism mediated by ER results in direct stimulation of aberrant cell proliferation, a factor causally related to breast cancer development [23, 24]. The ER-independent carcinogenic effects are believed to occur through the actions of genotoxic estrogen metabolites [23–26]. Parent estrogens undergo oxidative metabolism by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1B1 and CYP3A4 to form 2,3-catechol (2-OH-E1 and 2-OH-E2) and 3,4-catechol (4-OH-E1 and 4-OH-E2) estrogen metabolites. CYP1B1 has considerable regioselectivity (9:1) for formation of 4-OH-E1 and 4-OH-E2 [27]; it has been suggested that 4-OH-E1 and 4-OH-E2 are more genotoxic than the corresponding 2-OH-E1 and 2-OH-E2 metabolites [28, 29]. Furthermore, 2-OH-E2 is a potent inhibitor of aromatase [30] and 2-OH-E1 is associated with reduction of risk of ER+ breast cancer in postmenopausal women after adjustment for circulating estrone concentrations [31]. Both catechols are rapidly converted by catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) to methoxy (OMe) metabolites [32–34]. It is noteworthy that 2-OMe-E2 has significant anti-proliferative activity [35].

Estrogens and their hydroxylated metabolites are also readily modified by glucuronide, sulfate, or glutathione (GSH) moieties to give conjugated estrogen metabolites. The most abundant circulating estrogen conjugates are sulfates [36], which can serve as estrogen precursors in breast tissue through the action of steroid sulfatases [37, 38]. Circulating androgens can also serve as estrogen precursors in postmenopausal women (through the action of aromatase), which provides a fundamentally different source of estrogens when compared to the contributors to estrogen metabolites in premenopausal women [6, 31, 38]. Thus, considering their effects and metabolism, estrogens as well as their metabolites in the circulation are valuable biomarkers of tissue estrogen biosynthesis and metabolism [22, 39, 40].

2. Special considerations in ultra-high sensitivity required specimens

Typical serum concentrations in postmenopausal women and in older men for unconjugated E2 are often <5 pg/mL and for unconjugated E1 are 11.8–37.4 pg/mL [20, 41]. E2 levels in some pediatric endocrinology clinical studies were reported to be some 100-fold lower than those in adults, with the lowest levels in the pre-pubertal stages [42, 43]. These low pg/mL levels are very challenging for most LC-MS-based assays [6, 14, 41]. Furthermore, other unconjugated estrogen metabolites, such as MeO-estrogens or catechols, have even lower concentrations, with circulating levels generally below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of most LC-MS assays [6, 41, 44].

The sensitivity challenge for LC-MS-based procedures is due primarily to the low ionization efficiencies of unconjugated estrogens and their metabolites. Therefore, many derivatization strategies have been developed in order to improve ionization and increase sensitivity [4, 6, 14]. This also often also helps with sample clean up. Choosing fit-for-purpose sample preparation processes and establishing derivatization approaches are the first two considerations for ultra-high sensitivity analysis of estrogens in serum and plasma. It is less challenging to quantify total (unconjugated + conjugated) estrogens after hydrolysis or solvolysis because the total levels of estrogens are at least 2–3 fold higher than the unconjugated estrogens [6, 41, 44]. However, the evaluation of hydrolysis efficiency and uniformity across samples is still problematic and could give rise to erroneous results because some authentic standards and stable isotope standards are not available.

Notably, the evaluation of matrix effects is more complicated for analysis of estrogens when a suitable blank matrix is not available. The general approach is to prepare calibration standards and quality control (QC) samples in surrogate matrix, such as charcoal stripped serum [41, 45, 46]. However, analysts should be aware that calibration standards might not be truly representative of the unknown samples because components of real samples that cause matrix effect may be removed during the charcoal stripping process. Thus, spiking in isotope labeled internal standards (INSTDs) at the beginning of sample preparation as well as improving chromatographic separation of the isomers with longer LC gradients are important to ensure accurate absolute quantification. In addition, thorough method validation should be conducted to confirm the assay sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility prior to clinical samples analysis [5, 47].

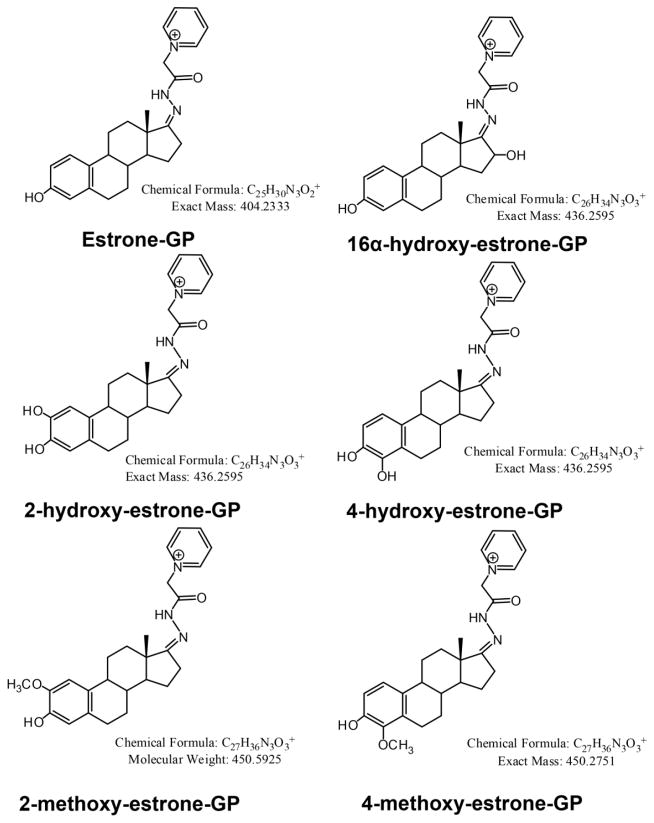

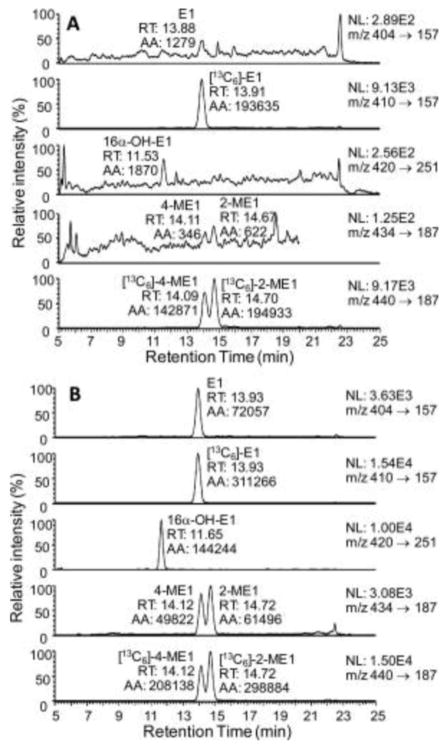

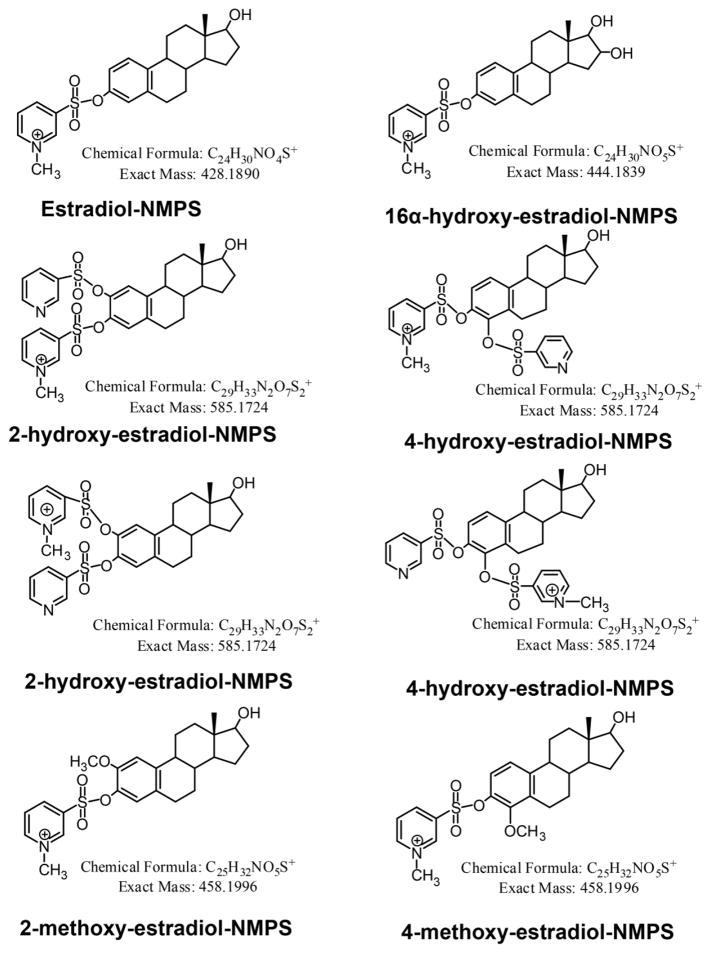

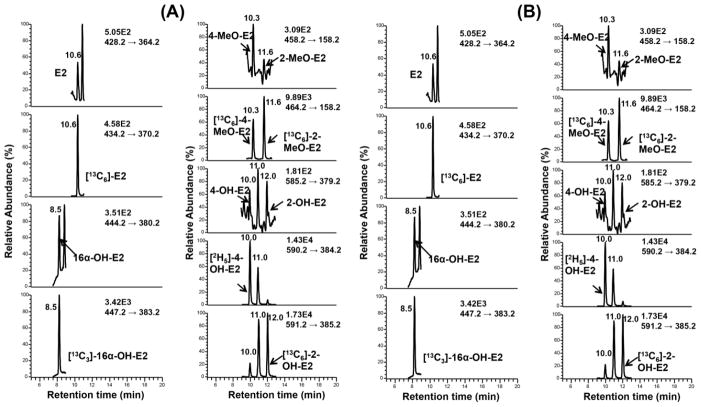

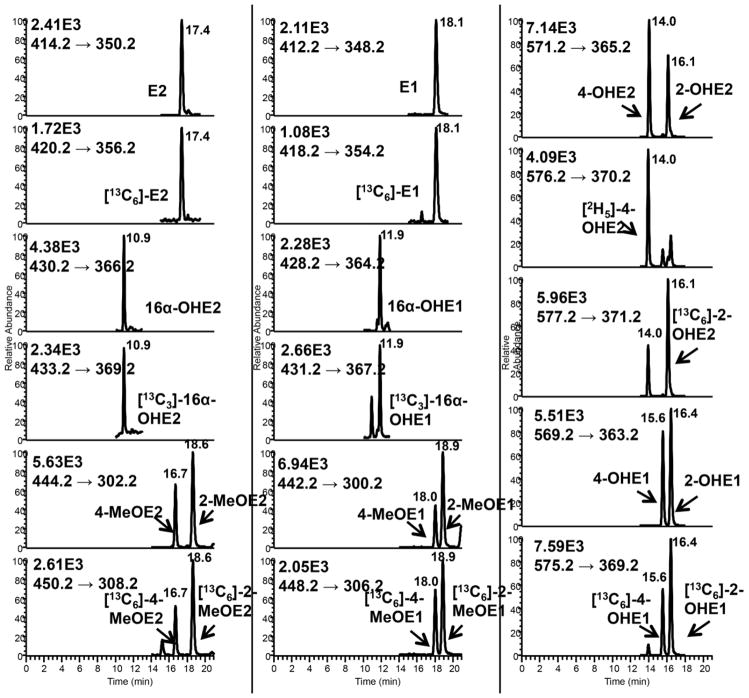

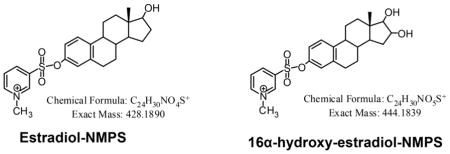

SID LC-SRM/MS methods are now accepted as the current ‘gold-standard’ to for quantification estrogen and their metabolites in serum or plasma of postmenopausal women [14]. For example, a high sensitivity SID-LC-SRM/MS method for analysis of E1 and its metabolites was reported in 2011, which employed the Girard P (GP) pre-ionized derivative that had been employed previously to analyze to keto steroids [48] (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). The high sensitivity allowed the use of only 0.5 mL of serum. The LLOQ for each estrogen was 0.156 pg/mL (15.6 fg on column). In 2015, a similar pre-ionization concept was implemented for E2 and its metabolites using the N-methyl pyridinium-3-sulfonyl (NMPS) derivative [41] (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). This method required only 0.1 mL of serum, and yet was capable of reaching 1.0 fg on column sensitivity for five estrogens and their metabolites.

Figure 1.

Girard P (GP) derivatives of estrone (E1) and its metabolites.

Figure 2.

LC-SRM/MS chromatograms for analysis of E1 and its metabolites extracted from double charcoal-stripped human serum as GP derivatives. A. LLOQ sample (0.156 pg/mL). B. HQC sample (16.0 pg/mL). E1, estrone, 16α-OH-E1, 16α-hydroxyestrone, 4-ME1, 4-methoxyestrone, 2-ME1, 2-methoxyestrone. Reprinted with permission from Rangiah et al. [35].

Figure 3.

N-methyl pyridine-3-sulfonyl (NMPS) derivatives of estradiol (E2) and its metabolites.

Figure 4.

LC-SRM/MS chromatograms for analysis of E2 and its metabolites extracted from double charcoal-stripped human serum as NMPS derivatives. A. LOQ sample (1.5 pg/mL). B. HQC sample (175.0 pg/mL). E2, estradiol, 16α-OH-E2, 16α-hydroxyestradiol, 4-MeO-E2, 4-methoxyestradiol, 2-MeO-E2, 2-methoxyestradiol, 4-OH-E2, 4-hydroxyestradiol, 2-OH-E2, 2-hydroxyestradiol. Adapted with permission from Wang et al. [31].

3. LC-tandem MS (MS/MS)-based assays for estrogen analysis

3.1. Sample preparation

Sample preparation for analysis of serum and plasma estrogen analysis by LC-MS/MS-based methods such as LC-SRM/MS typically involves extraction, clean up, and concentration. For the conjugated estrogens, hydrolysis can be performed before analysis, or they can be quantified as intact conjugates. The hydrolysis step converts the conjugates into unconjugated forms, hence increasing their concentration in the sample. Subsequent liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) or solid phase extraction (SPE) can be employed to efficiently extract estrogens from serum and plasma [2, 49].

LLE is inexpensive, fast, and often the primary extraction for estrogen analysis. Some drawbacks of LLE are that it is labor-intensive, time-consuming and harder to automate than SPE. The solvents most commonly used are methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), diethyl ether, dichloromethane or mixtures of organic solvents. MTBE can be used to extract both unconjugated estrogen from serum samples and estrogen derivatives from derivatization buffer [41, 48]. A thorough investigation of extraction efficiency for MTBE, diethyl ether, hexane and 2-methylbutane from serum samples was reported by Keski-Rahkonen et al. [50]. This study showed that LLE with MTBE fully recovered the tested steroid hormones in contrast to the other solvents.

Off-line or on-line SPE coupled with LC-MS is a very promising technique for semi-automated sample analysis. Advantages of on-line SPE include shorter analysis time, more concentrated chromatographic band and greatly reducing of contaminations. One study by Zhao et al. reported a LC-MS method for determination of 12 unconjugated estrogens and their intact conjugates in blood and urine [51]. This method used only one SPE step for both unconjugated estrogens and their conjugates. After loading samples on an Oasis HLB (hydrophilic-lipophilic balance) cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA), unconjugated estrogens were first eluted with ethyl acetate, and conjugates were then eluted with methanol containing 0.1% ammonium hydroxide. A more recent study reported an automated on-line trap-and-elute sample treatment process by using a weak cation exchange (WCX) restricted access material (RAM) trap column (Waters) and on-line dilution [52]. This approach has potential application to older men, children, and postmenopausal women samples since the streamlined procedure requires only 100 μL of serum and an LLOQ of 3 pg/mL with excellent accuracy and precision.

Two approaches have been employed for the analysis of conjugated estrogens. The first approach involves hydrolysis of β-glucuronide and sulfate conjugates before extraction and derivatization steps. The most often used enzyme is β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase purified from the snail, Helix pomatia [46, 53–55]. The enzyme from Helix pomatia naturally contains β-glucuronidase and sulfatase activities in almost equal amounts. In contract, the enzyme from E. coli contains only β-glucuronidase and is essentially free of sulfatase activity. However, some evidences showed that Helix pomatia extract is contaminated with 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) or cholesterol oxidase activity and could confound studies in which the analytes of interest are 3β-HSD substrates [56]. This is a very important issue if androgens are being analyzed in the same sample. Experiments performed with synthesized estrogen sulfate conjugates showed that only the 3-sulfate is cleavage by enzymatic hydrolysis, whereas the 17-sulfate group is resistant to the enzymatic hydrolysis [57]. A promising method for overcoming this problem involves solvolysis of the conjugates with anhydrous methanolic hydrogen chloride an approach that was first published by Tang and Crone in 1989 [58]. Several groups have used this approach subsequently [57, 59]. Surprisingly, it does not appear to have been employed in studies conducted with serum and plasma samples from older men, children, and postmenopausal women.

The second approach involves analysis of the intact conjugate by MS in negative ion mode without enzyme hydrolysis or derivatization. Recent studies observed that total E1 concentration in postmenopausal women is in the range of 61.3 to 442.1 pg/mL including E1 sulfate at mean concentration of 244.8 pg/mL [6, 44]. These higher levels of E1 glucuronide or E1 sulfate could easily be quantified by an LC-MS-based method. E1 sulfate in serum samples can be efficiently extracted using Oasis HLB [60, 61] or weak anion exchange (WAX) cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) [62] and eluted with ammonium acetate or ammonium hydroxide. The use of intact conjugates is very promising but is hampered by the lack of authentic estrogen conjugate standards and heavy stable isotope analogs for use as internal standards. For example, only 17 β-E2-2,4,6-[2H]4-3-sulfate is currently available among five possible E2 sulfates (3-sulfate, 17-sulfate, 3-sulfate 17-glucuronide, 3-glucuronide 17-sulfate, 3-,17-bis-sulfate).

3.2. Derivatization

Due to the extremely low concentrations of unconjugated estrogens in serum or plasma in older men, children, and postmenopausal women, it is currently necessary to employ derivatization approaches for reliable measurement. A number of chemical derivatization reagents have been used with the purpose of improving the estrogen ionization efficiencies. The derivatization of the phenolic hydroxyl group of estrogen by pentafluorobenzyl (PFB) [63], pyridyl-3-sulfonyl (PS) [64], dansyl (D) [65–67], 2-picolinoyl (P) [68], N-methyl-2-pyridinyl (NMP) [69], N-methyl-nicotinoyl (NMN) [70], 1-(2,4-dinitro-5-fluorophenyl)-4,4-dimethylpiperazinyl (MPPZ) [71], 3-pentaflurobenzyl-17β-pyridinium (PFBPY) [72] and 1,2-dimethylimidazole-5-sulfonyl chloride (DMIS) [73] derivatives have all been reported in the recent literature. Most of the derivatives (PFB, PNB, PS, D, P-derivatives) do not carry a charge on the molecule, which limits their ability to reach low pg/mL detection limits. Furthermore, due to the chemical similarity of estrogens, the derivatives tend to provide nonspecific fragmentation patterns, which causes poor analytical specificity. The MP, NMN, MPPZ, PFBPY and DMIS derivatives carry a permanent charge making them more amenable to reaching pg/mL sensitivity range. Recently, we developed a new pre-ionized derivatization procedure, which formed E2 and its metabolites as pre-ionized N-methyl pyridinium-3-sulfonyl (NMPS) derivatives. The LLOQ of 1.0 fg on column with 1μL injection volume makes it very powerful to absolutely quantify unconjugated estrogens in serum samples from postmenopausal women and older men [41]. The derivatization occurs at the phenolic hydroxyl group making the method generalizable to the all of the estrogens. As with any high sensitivity analysis, caution should be taken since small amounts of contamination or carryover from a previous injection, or background from processing may affect the quality of the data. It is particularly important to utilize and appropriate blank matrix to check system background including tubes, extract solvent, derivatization buffer and derivatization solvent used in the sample preparation, and the instrument itself. Therefore tubes, reagents, and enzymes should be pre-tested to make sure they will not bring any contamination or interference for determination of estrogen [14]. For example, we unexpectedly found that some glass tubes cause interference into the E2 signal (equivalent to approximately 10 pg/mL in serum) during enzymatic hydrolysis.

3.3 Chromatographic separation

In LC-SRM/MS-based estrogen quantification, interference arising from isobaric exogenous or endogenous estrogens and other steroids can be a critical factor [2, 74]. Unfortunately, estrogens and their metabolites tend to form similar product ions on collision-induced dissociation (CID) in analysis by tandem MS (MS/MS) [65–67]. For example, the product ion m/z 171 is commonly selected as a quantifier or qualifier of all estrogens and their metabolites, which originated from dansyl group when dansyl-derivatives are analyzed. Therefore, if E1 and its metabolites are not chromatographically separated from E2 and its metabolites, overestimation of unconjugated E2 may occur since unconjugated E1 is usually 2–3 folds higher. It is more challenging to accurately quantify 2- and 4-OH-E1 and 2- and 4-OH-E2 and their corresponding methoxy-metabolites because the individual isomers must be chromatographically separated from each other. In this regard, increasing peak capacity and optimization of gradient elution are helpful strategies. Furthermore, particle size of the stationary phase can have a profound effect on peak performance and increasingly sub 2 μm particles are used to improve chromatographic capacity as well as sensitivity and speed of analysis [75, 76]. For example, in our recent study, 12 estrogen metabolites can be successfully separated on Waters BEH130 C18 column (150 μm × 100 mm, 1.7μm, 130 A) within 45 min following pyridinium sulfonyl derivatization including four catechol estrogens (4-OHE1, 2-OHE1, 4-OHE2, 2-OHE2) and four MeO-estrogens (4-MeOE1, 2-MeOE1, 4-MeOE2, 2-MeOE2) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

LC-SRM/MS chromatograms for analysis of estrogens and their metabolites extracted from double charcoal-stripped human serum as pyridinium sulfonyl (PS) derivatives.

3.4 Matrix effects

Serum or plasma contains components such as phospholipids and salts which may enhance or suppress the ionization efficiency of estrogen. Furthermore, Keski-Rahkonen et al. encountered matrix effects when LC-MS-based assay was performed in test tubes or well plates made of plastic [50]. Matrix effects have been designated as the potential “Achilles heel” of LC-MS/MS-based analyses of biological samples [77]. In LC-MS and LC-SRM/MS especially, it is important to be aware that the co-eluting compounds will not be always seen in the monitored ranges or transitions, as part of a phenomenon termed “ghost peaks”.

For estrogens analysis, positive mode electrospray ionization (ESI) is the most widely used ionization type after conducting derivatization, but it has been argued to be more susceptible to ion suppression than atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) [44, 78]. However, it was shown that underivatized E2 had at least a 10-fold increase in sensitivity in the ESI negative mode when compared with atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI) in the positive mode and did not suffer from interference by co-eluting isobaric compounds [79]. To assess the matrix effects there are three general strategies: (1) post-column infusion, (2) post-extraction addition and (3) a comparison of the slopes of calibration curve. The details of these assessment approaches were discussed in several reviews [80, 81]. FDA guidance from 2013 suggests that appropriate steps should be taken to ensure the lack of matrix effects throughout the application of the method, especially if the matrix used for production batches is different from the matrix used during method validation. Also, the acceptance criteria are that the measured value should be within the 15% bias range of the nominal value while the CV should be less than 15% [82]. For estrogens quantification, reducing matrix effects has been suggested by improving the sample preparation procedure [83], optimizing chromatographic separation [74], or employing stable isotope labeled internal standards [4]. Caution with [2H]-analog internal standards should be taken, as a shift in retention time between unlabeled and [2H]-labeled compounds can be analytically significant. This can lead to differential suppression of the signals from the analyte and internal standard [84]. Ideally, [13C]-containing analogs of the target analytes should be used as internal standards since they exactly co-elute under all chromatographic conditions [84]. Furthermore, they eliminate the possibility of potential deuterium exchange in protic solvents. With the better chromatographic resolution provided by the sub 2 μm particles, larger separation between analytes and their corresponding [2H]-analogs could occur, which would further reduce the benefit of internal standard. For example, Berg and Strand investigated the use of [2H]- and [13C]-analog internal standards using an ultraperformance LC-MS/MS-based method and observed an improved ability to compensate for ion suppression effects when [13C]-analog were used [85]. Fortunately, most of the [13C]-analog internal standards are available for estrogens and their metabolites except for 2-OH-E2.

3.4 Assay validation

Prior to implementing a clinical study, any developed LC-MS method must be rigorously validated to ensure assay reliability [82]. Fundamental parameters for this validation include accuracy, precision, selectivity, sensitivity, reproducibility and stability. It is particularly important to ensure that the assay is accurate because it is relatively easy to ensure LC-MS assays are precise. This means that the authentic standards must be pure and that all standard solutions are monitored by HPLC-UV and are calculated by their extinction coefficient for any decomposition during storage.

Typically, accuracy and precision are evaluated by intra-batch or inter-batch spike-in QC samples. Recovery and matrix effects are then determined by comparing the accuracy and precision data from both surrogate matrix and the actual serum matrix. The spike-in QC samples usually are prepared in a matrix, which lacks the endogenous estrogen and analyzed in replicates of three to five over several days. However, the use of endogenous QCs as well as spike-in QCs can be extremely helpful for monitoring assay performance [45]. The endogenous QC samples are prepared in a pooled serum of unstripped serum, which contains estrogens and their metabolites. LQC, MQC and HQC serum samples are then prepared by spiking at known concentration with an appropriate QC working solution. Caution should be taken when evaluating matrix effect using surrogate matrices (e.g. charcoal striped serum) since some components of real serum or plasma samples might be removed during their preparation [41, 45]. It is noteworthy that other approaches have been used to evaluate assays without the use of surrogate matrices, such as generating calibration curves by stable isotope labeled analog internal standards coupled with standard addition [45, 75].

Another technique that is often used to confirm assay accuracy is to conduct a standard curve in water or buffer. The regression line should be parallel to that observed in serum or plasma and the intercept on the x-axis of the serum or plasma regression lines should correspond to the negative value for the endogenous analyte concentration. Before implementing a validated LC-SRM/MS-based assay on a large scale of real samples, it is valuable to compare the initial data with other available assays by analyzing a small set of patient samples. Data agreement between two methods should be assessed with a Deming regression [86] and by a Bland Altman comparison [87]. This will help to identify potential problems with the assay, especially those related to endogenous metabolites and matrix effects. It is of particular concern to minimize suppression of ionization from the matrix when using ESI/MS-based methods because this can affect the accuracy of analyses close to the LLOQ where, unfortunately, many samples from postmenopausal women tend to lie.

4. Future perspectives

It is clear that the analysis of estrogens as biomarkers for many endocrine disorders will continue to be an important area for research and there may continue to be a role for RIA-based procedures as long as specific antibodies reagents employed, and assay robustness carefully monitored [47]. SID LC-SRM/MS procedures can potentially provide a gold standard for assessing such procedures [14]. However, as assay sensitivity has increased such as by the use of pre-ionized derivative [41], the potential for interfering substances that elute with similar retention times to the estrogens of interest has also increased. This poses a great dilemma for the analyst particularly with serum or plasma samples that are close to the LLOQ. Often the use of alternative LC stationary phases or changes in extraction procedure cannot resolve the problem and so samples have to be classified as below the detection limit. Fortunately, the availability of instrumentation with higher resolution could potentially provide a solution to this dilemma. For triple quadrupole instruments, the high sensitivity Triple TOF mass spectrometer (Sciex, Redwood City, CA) can operate at a resolution of 30,000. It will be interesting to determine whether this substantial increase in resolution over conventional triple quadruple instruments (typically 1,000) can improve selectivity. Alternatively, the new hybrid quadrupole/Orbitrap high resolution Q-Exactive HF instruments (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA), can routinely offer resolutions exceeding 150,000 with chromatographically compatible scan speeds [88] and provide an alternative approach. It is noteworthy that one study using a previous generation of Q-Exactive, when coupled with the use of 1-methylimidazole-2-sulfonyl estrogen derivatives, provided substantial improvements to sensitivity and specificity as compared with current triple quadrupole-based methodology [89].

The wider availability of higher resolution instruments coupled with their improved sensitivity suggests that the analysis of intact estrogen conjugates will be introduced as a more specific approach compared with the enzymatic hydrolysis procedures that currently predominate. Two major problems that have to be overcome are the lack of appropriate standards and the potential segregation of the LC-MS signal for a specific estrogen into numerous glucuronide and sulfate conjugates. The ultra-high sensitivity and resolution of instruments such as the Thermo Q-Exactive HF Orbitrap should overcome the problem of analyzing numerous conjugates. However, there is a real need for synthetic approaches to build upon the excellent studies of Caron et al. [1] to make available appropriate labeled and unlabeled standards. As the importance of estrogen biomarkers for breast cancer risk is more widely recognized, it seems realistic to assume that these standards will become available in the not too distant future. Finally, there is a real need to implement routine specific assays for urinary estrogen DNA-adducts [90] in order to more fully test the hypothesis that estrogens could induce cancer through a genotoxic mechanism [91].

Highlights.

It remains an analytical challenge to quantify estrogens and their metabolites in specimens from special populations.

Estrogen levels are at pg/mL in serum or plasma samples from older men, children, postmenopausal women and women receiving aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer treatment.

Stable isotope dilution LC-SRM/MS assays provide high specificity and accuracy.

Estrogen derivatives facilitate ultra-high sensitivity LC-SRM/MS-based analysis.

Suggested practices for ultra-high sensitivity LC-SRM/MS-based methodology are reviewed

Future perspectives on the use of high-resolution mass spectrometry are discussed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Caron P, Audet-Walsh E, Lepine J, Belanger A, Guillemette C. Profiling endogenous serum estrogen and estrogen-glucuronides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:10143–10148. doi: 10.1021/ac9019126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushnir MM, Rockwood AL, Roberts WL, Yue B, Bergquist J, Meikle AW. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for analysis of steroids in clinical laboratories. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellem A, Meiyappan S, Romans S, Einstein G. Measuring estrogens and progestagens in humans: an overview of methods. Gend Med. 2011;8:283–299. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair IA. Analysis of estrogens in serum and plasma from postmenopausal women: past present, and future. Steroids. 2010;75:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demers LM, Hankinson SE, Haymond S, Key T, Rosner W, Santen RJ, et al. Measuring Estrogen Exposure and Metabolism: Workshop Recommendations on Clinical Issues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2165–2170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, Bottalico L, Mesaros C, Blair IA. Analysis of estrogens and androgens in postmenopausal serum and plasma by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2015;99:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penning TM, Lee SH, Jin Y, Gutierrez A, Blair IA. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) of steroid hormone metabolites and its applications. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:546–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouveia MJ, Brindley PJ, Santos LL, Correia da Costa JM, Gomes P, Vale N. Mass spectrometry techniques in the survey of steroid metabolites as potential disease biomarkers: a review. Metabolism. 2013;62:1206–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shackleton C. Clinical steroid mass spectrometry: a 45-year history culminating in HPLC-MS/MS becoming an essential tool for patient diagnosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black A, Pinsky PF, Grubb RL, Falk RT, III, Hsing AW, Chu L, et al. Sex steroid hormone metabolism in relation to risk of aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:2374–2382. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauh M. Steroid measurement with LC-MS/MS. Application examples in pediatrics. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauh M. Steroid measurement with LC-MS/MS in pediatric endocrinology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;301:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honour JW. Steroid assays in paediatric endocrinology. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2:1–16. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.v2i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mesaros C, Wang Q, Blair IA. What are the main considerations for bioanalysis of estrogens and androgens in plasma and serum samples from postmenopausal women? Bioanalysis. 2014;6:3073–3075. doi: 10.4155/bio.14.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SB, Hankinson SE. Endogenous estrogens and the risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers. Steroids. 2015;99:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson SH, Bandera EV, Orlow I. Variants in estrogen biosynthesis genes, sex steroid hormone levels, and endometrial cancer: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:235–245. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizner TL. Estrogen biosynthesis, phase I and phase II metabolism, and action in endometrial cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;381:124–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliassen AH, Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormone levels and risk of breast, endometrial and ovarian cancers: prospective studies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;630:148–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartman J, Strom A, Gustafsson JA. Current concepts and significance of estrogen receptor beta in prostate cancer. Steroids. 2012;77:1262–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosner W, Hankinson SE, Sluss PM, Vesper HW, Wierman ME. Challenges to the measurement of estradiol: an endocrine society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1376–1387. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabat GC, O’Leary ES, Gammon MD, Sepkovic DW, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, et al. Estrogen metabolism and breast cancer. Epidemiology. 2006;17:80–88. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000190543.40801.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziegler RG, Fuhrman BJ, Moore SC, Matthews CE. Epidemiologic studies of estrogen metabolism and breast cancer. Steroids. 2015;99:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue W, Yager JD, Wang JP, Jupe ER, Santen RJ. Estrogen receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms of breast cancer carcinogenesis. Steroids. 2013;78:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santen RJ, Yue W, Wang JP. Estrogen metabolites and breast cancer. Steroids. 2015;99:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemon HM. Abnormal estrogen metabolism and tissue estrogen receptor proteins in breast cancer. Cancer. 1970;25:423–435. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197002)25:2<423::aid-cncr2820250222>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liehr JG. Genotoxicity of the steroidal oestrogens oestrone and oestradiol: possible mechanism of uterine and mammary cancer development. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:273–281. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanna IH, Dawling S, Roodi N, Guengerich FP, Parl FF. Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) pharmacogenetics: association of polymorphisms with functional differences in estrogen hydroxylation activity. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3440–3444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalieri E, Chakravarti D, Guttenplan J, Hart E, Ingle J, Jankowiak R, et al. Catechol estrogen quinones as initiators of breast and other human cancers: implications for biomarkers of susceptibility and cancer prevention. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1766:63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang M, Peng KW, Kastrati I, Overk CR, Qin ZH, Yao P, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor-mediated gene transcription by the equine estrogen metabolite, 4-methoxyequilenin, in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4793–4802. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neves MA, Dinis TC, Colombo G, Melo Luisa Sa E. Biochemical and computational insights into the anti-aromatase activity of natural catechol estrogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arslan AA, Koenig KL, Lenner P, Afanasyeva Y, Shore RE, Chen Y, et al. Circulating estrogen metabolites and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1290–1297. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavigne JA, Goodman JE, Fonong T, Odwin S, He P, Roberts DW, et al. The effects of catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition on estrogen metabolite and oxidative DNA damage levels in estradiol-treated MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7488–7494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yager JD. Endogenous estrogens as carcinogens through metabolic activation. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000:67–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yager JD. Mechanisms of estrogen carcinogenesis: The role of E2/E1-quinone metabolites suggests new approaches to preventive intervention - A review. Steroids. 2015;99:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dawling S, Roodi N, Mernaugh RL, Wang X, Parl FF. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated metabolism of catechol estrogens: comparison of wild-type and variant COMT isoforms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6716–6722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hobkirk R. Steroid sulfotransferases and steroid sulfate sulfatases: characteristics and biological roles. Can J Biochem Cell Biol. 1985;63:1127–1144. doi: 10.1139/o85-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purohit A, Woo LW, Potter BV. Steroid sulfatase: a pivotal player in estrogen synthesis and metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;340:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purohit A, Foster PA. Steroid sulfatase inhibitors for estrogen- and androgen-dependent cancers. J Endocrinol. 2012;212:99–110. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santen RJ, Yue W, Wang JP. Estrogen metabolites and breast cancer. Steroids. 2015;99:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziegler RG, Faupel-Badger JM, Sue LY, Fuhrman BJ, Falk RT, Boyd-Morin J, et al. A new approach to measuring estrogen exposure and metabolism in epidemiologic studies. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Q, Rangiah K, Mesaros C, Snyder NW, Vachani A, Song H, et al. Ultrasensitive quantification of serum estrogens in postmenopausal women and older men by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2015;96:140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahhal SN, Fuqua JS, Lee PA. The impact of assay sensitivity in the assessment of diseases and disorders in children. Steroids. 2008;73:1322–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demers LM. Testosterone and estradiol assays: current and future trends. Steroids. 2008;73:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdel-Khalik J, Bjorklund E, Hansen M. Simultaneous determination of endogenous steroid hormones in human and animal plasma and serum by liquid or gas chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;928:58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ke Y, Bertin J, Gonthier R, Simard JN, Labrie F. A sensitive, simple and robust LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of seven androgen- and estrogen-related steroids in postmenopausal serum. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144(Pt B):523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu X, Roman JM, Issaq HJ, Keefer LK, Veenstra TD, Ziegler RG. Quantitative measurement of endogenous estrogens and estrogen metabolites in human serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7813–7821. doi: 10.1021/ac070494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santen RJ, Demers LM, Ziegler RG. Workshop on measuring estrogen exposure and metabolism: Summary of the presentations. Steroids. 2015;99:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rangiah K, Shah SJ, Vachani A, Ciccimaro E, Blair IA. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry of pre-ionized Girard P derivatives for quantifying estrone and its metabolites in serum from postmenopausal women. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25:1297–1307. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdel-Khalik J, Bjorklund E, Hansen M. Simultaneous determination of endogenous steroid hormones in human and animal plasma and serum by liquid or gas chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;928:58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keski-Rahkonen P, Huhtinen K, Poutanen M, Auriola S. Fast and sensitive liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry assay for seven androgenic and progestagenic steroids in human serum. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Y, Boyd JM, Sawyer MB, Li XF. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry determination of free and conjugated estrogens in breast cancer patients before and after exemestane treatment. Anal Chim Acta. 2014;806:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beinhauer J, Bian L, Fan H, Sebela M, Kukula M, Barrera JA, et al. Bulk derivatization and cation exchange restricted access media-based trap-and-elute liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method for determination of trace estrogens in serum. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;858:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dallal CM, Tice JA, Buist DS, Bauer DC, Lacey JV, Jr, Cauley JA, et al. Estrogen metabolism and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women: a case-cohort study within B~FIT. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:346–355. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Falk RT, Brinton LA, Dorgan JF, Fuhrman BJ, Veenstra TD, Xu X, et al. Relationship of serum estrogens and estrogen metabolites to postmenopausal breast cancer risk: a nested case-control study. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R34. doi: 10.1186/bcr3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao W, Zeng C, Cai D, Liu B, Li Y, Wen X, et al. Serum concentrations of selected endogenous estrogen and estrogen metabolites in pre- and post-menopausal Chinese women with osteoarthritis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:644–649. doi: 10.1007/BF03346664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tamae D, Byrns M, Marck B, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Lange P, et al. Development, validation and application of a stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography electrospray ionization/selected reaction monitoring/mass spectrometry (SID-LC/ESI/SRM/MS) method for quantification of keto-androgens in human serum. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;138:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hobe G, Schon R, Goncharov N, Katsiya G, Koryakin M, Gesson-Cholat I, et al. Some new aspects of 17alpha-estradiol metabolism in man. Steroids. 2002;67:883–893. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang PW, Crone DL. A new method for hydrolyzing sulfate and glucuronyl conjugates of steroids. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90596-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong CH, Leung DK, Tang FP, Wong JK, Yu NH, Wan TS. Rapid screening of anabolic steroids in horse urine with ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry after chemical derivatisation. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1232:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Labrie F, Belanger A, Belanger P, Berube R, Martel C, Cusan L, et al. Metabolism of DHEA in postmenopausal women following percutaneous administration. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Labrie F, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Cote I, Berube R, Belanger P, et al. Effect of intravaginal DHEA on serum DHEA and eleven of its metabolites in postmenopausal women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;111:178–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dury AY, Ke Y, Gonthier R, Isabelle M, Simard JN, Labrie F. Validated LC-MS/MS simultaneous assay of five sex steroid/neurosteroid-related sulfates in human serum. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;149:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh G, Gutierrez A, Xu K, Blair IA. Liquid chromatography/electron capture atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/mass spectrometry: analysis of pentafluorobenzyl derivatives of biomolecules and drugs in the attomole range. Anal Chem. 2000;72:3007–3013. doi: 10.1021/ac000374a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu L, Spink DC. Analysis of steroidal estrogens as pyridine-3-sulfonyl derivatives by liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2008;375:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson RE, Grebe SK, Kane ODJ, Singh RJ. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of estradiol and estrone in human plasma. Clin Chem. 2004;50:373–384. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tai SS, Welch MJ. Development and evaluation of a reference measurement procedure for the determination of estradiol-17beta in human serum using isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6359–6363. doi: 10.1021/ac050837i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu X, Veenstra TD, Fox SD, Roman JM, Issaq HJ, Falk R, et al. Measuring fifteen endogenous estrogens simultaneously in human urine by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6646–6654. doi: 10.1021/ac050697c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamashita K, Okuyama M, Watanabe Y, Honma S, Kobayashi S, Numazawa M. Highly sensitive determination of estrone and estradiol in human serum by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2007;72:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin YH, Chen CY, Wang GS. Analysis of steroid estrogens in water using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry with chemical derivatizations. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1973–1983. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang WC, Regnier FE, Sliva D, Adamec J. Stable isotope-coded quaternization for comparative quantification of estrogen metabolites by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;870:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nishio T, Higashi T, Funaishi A, Tanaka J, Shimada K. Development and application of electrospray-active derivatization reagents for hydroxysteroids. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44:786–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arai S, Miyashiro Y, Shibata Y, Kashiwagi B, Tomaru Y, Kobayashi M, et al. New quantification method for estradiol in the prostatic tissues of benign prostatic hyperplasia using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2010;75:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keski-Rahkonen P, Desai R, Jimenez M, Harwood DT, Handelsman DJ. Measurement of Estradiol in Human Serum by LC-MS/MS Using a Novel Estrogen-Specific Derivatization Reagent. Anal Chem. 2015;87:7180–7186. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Settlage J, Oglesby T, Rajasekaran A, Williard C, Scott G. The importance of chromatographic resolution when analyzing steroid biomarkers. Steroids. 2015;99:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Couchman L, Vincent RP, Ghataore L, Moniz CF, Taylor NF. Challenges and benefits of endogenous steroid analysis by LC-MS/MS. Bioanalysis. 2011;3:2549–2572. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Keevil BG. Novel liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods for measuring steroids. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taylor PJ. Matrix effects: the Achilles heel of quantitative high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Souverain S, Rudaz S, Veuthey JL. Matrix effect in LC-ESI-MS and LC-APCI-MS with off-line and on-line extraction procedures. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1058:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guo T, Gu J, Soldin OP, Singh RJ, Soldin SJ. Rapid measurement of estrogens and their metabolites in human serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry without derivatization. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van EA, Lanckmans K, Sarre S, Smolders I, Michotte Y. Validation of bioanalytical LC-MS/MS assays: evaluation of matrix effects. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:2198–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Novakova L. Challenges in the development of bioanalytical liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method with emphasis on fast analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1292:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm368107.pdf. 2013. Ref Type: Online Source

- 83.Harwood DT, Handelsman DJ. Development and validation of a sensitive liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay to simultaneously measure androgens and estrogens in serum without derivatization. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;409:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ciccimaro E, Blair IA. Stable-isotope dilution LC-MS for quantitative biomarker analysis. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:311–341. doi: 10.4155/bio.09.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berg T, Strand DH. (1)(3)C labelled internal standards--a solution to minimize ion suppression effects in liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analyses of drugs in biological samples? J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:9366–9374. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stockl D, Dewitte K, Thienpont LM. Validity of linear regression in method comparison studies: is it limited by the statistical model or the quality of the analytical input data? Clin Chem. 1998;44:2340–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bland JM, Altman DG. Agreed statistics: measurement method comparison. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:182–185. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823d7784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eliuk S, Makarov A. Evolution of Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry Instrumentation. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif ) 2015;8:61–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-071114-040325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li X, Franke AA. Improved profiling of estrogen metabolites by orbitrap LC/MS. Steroids. 2015;99:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bransfield LA, Rennie A, Visvanathan K, Odwin SA, Kensler TW, Yager JD, et al. Formation of two novel estrogen guanine adducts and HPLC/MS detection of 4-hydroxyestradiol-N7-guanine in human urine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1622–1630. doi: 10.1021/tx800145w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mauras N, Santen RJ, Colon-Otero G, Hossain J, Wang Q, Mesaros C, et al. Estrogens and Their Genotoxic Metabolites Are Increased in Obese Prepubertal Girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2322–2328. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]