Abstract

Acinetobacter johnsonii is generally recognized as a nonpathogenic bacterium although it is often found in hospital environments. However, a newly identified isolate of this species from a frost-plant-tissue sample, namely, A. johnsonii MB44, showed significant nematicidal activity against the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans. To expand our understanding of this bacterial species, we generated a draft genome sequence of MB44 and analyzed its genomic features related to nematicidal attributes. The 3.36 Mb long genome contains 3636 predicted protein-coding genes and 95 RNA genes (including 14 rRNA genes), with a G + C content of 41.37 %. Genomic analysis of the prediction of nematicidal proteins using the software MP3 revealed a total of 108 potential virulence proteins. Some of these proteins were homologous to the known virulent proteins identified from Acinetobacter baumannii, a pathogenic species of the genus Acinetobacter. These virulent proteins included the outer membrane protein A, the phospholipase D, and penicillin-binding protein 7/8. Moreover, one siderophore biosynthesis gene cluster and one capsular polysaccharide gene cluster, which were predicted to be important virulence factors for C. elegans, were identified in the MB44 genome. The current study demonstrated that A. johnsonii MB44, with its nematicidal activity, could be an opportunistic pathogen to animals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2668-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acinetobacter johnsonii, Genome, Nematicidal activity

Background

Bacterial species of the genus Acinetobacter are ubiquitous in nature and are usually found in the hospital environment; some of these species have been implicated in a variety of nosocomial infections (Bergogne-Berezin and Towner 1996). For instance, Acinetobacter baumannii is known as a global nosocomial pathogen for its ability to cause hospital outbreaks and develop antibiotic resistance (Dijkshoorn et al. 2007; Peleg et al. 2008); A. pittii and A. nosocomialis have been reported to be associated with human infections (Chuang et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2013). Certain Acinetobacter species are currently emphasized in discussions on pathogenicity and mechanisms of multidrug resistance. However, the species A. johnsonii, which was identified to encode an extended-spectrum β-lactamase that confers resistance against penicillins, cephalosporins, and monobactams (Zong 2014), has been scarcely reported to cause animal or human disease.

In this study, an A. johnsonii MB44 strain was isolated from a frost-plant-tissue sample in the process of screening for ice-nucleating bacteria (Li et al. 2012). Bioassay reveals the significant virulence of this strain against the model organism, Caenorhabditis elegans. To date, the human-pathogen A. baumannii and A. nosocomialis have been reported for their pathogenicity against C. elegans (Vila-Farres et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2004). Therefore, to identify the potential virulence factors and better understand the molecular mechanism of its ability to infect nematodes, we performed genome sequencing of A. johnsonii MB44. The genomic features and the potential nematode-virulent genes were reported herein.

Methods

Bacterial culture and genomic DNA preparation

A clonal population of A. johnsonii strain MB44 was derived from a single colony serially passaged three times. The bacterium was grown under incubation at 28 °C on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates (1.5 % agar) containing 0.5 % NaCl. Colonies were inoculated into 5 mL of LB medium with shaking at 28 °C for 24 h. Aliquots (250 μL) from the LB cultures were inoculated into 25 mL of LB broth in a 100 mL flask and incubated at 28 °C for 20 h. Cells were pelleted successively into one 1.5 mL centrifuge tube at 12,000 rpm. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Bacterial DNA Kit (GBCBIO), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quality and quantity were determined with a Nanodrop spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA).

Nematode toxicity bioassay

For pathogenicity assay, C. elegans strain N2 was maintained at NGM agar with E. coli OP50 as food source. Assay was conducted with age synchronized L4 stage worms. A. johnsonii MB44 was grown in LB broth for 24 h. The cells were collected, re-suspended, and diluted in M9 buffer to make desired initial concentrations (based on OD600). Assay was conducted in 96 well plate such as each well contained 150 µL of cell suspension, 5 µL of 8 mM 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUdR), 40 µL M9 buffer and 40–50 L4 worms. Killing of worms was observed after 72 h.

Phylogenetic analysis

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the reference strains used for phylogenetic analysis were obtained from GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Benson et al. 2015). To construct the phylogenetic tree, these sequences were collected and nucleotide sequence alignment was carried out using ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994). The software MEGA v.5.05 (Tamura et al. 2011) was used to generate phylogenetic trees based on 16S rRNA genes under the neighbor-joining approach (Saitou and Nei 1987).

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of MB44 was sequenced by a commercial service at Beijing BerryGenomics Co., Ltd. using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Genomic DNA was sequenced with the Illumina sequencing platform by the paired-end strategy (2 × 125 bp) and the details of library construction and sequencing can be found at the Illumina website, yielding 8,593,104 total reads and providing 137-fold coverage of the genome. ABySS v.1.3.7 (Simpson et al. 2009) was employed for sequence assembly and the optimal value of k-mer is 90. The final draft assembly contained 75 contigs and the total size of the genome is 3.36 Mb. Contigs were ordered based upon Acinetobacter lwoffii WJ10621 (Hu et al. 2011) as reference genome using Mauve (Darling et al. 2004). The circular genome of A. johnsonii MB44 was generated using Artemis (Rutherford et al. 2000).

Genome annotation

Automated genome annotation was completed by the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/). The coding sequences (CDSs) were predicted using software Glimmer v.3.02 (Delcher et al. 2007). The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the NCBI non-redundant database, UniProt, and Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) databases. The whole genomic tRNAs were identified using tRNAscan-SE v.1.21 (Lowe and Eddy 1997), and rRNAs were found by RNAmmer v.1.2 Server (Lagesen et al. 2007). Genes with signal peptides were predicted by SignalP (Petersen et al. 2011). In addition, genes carrying trans-membrane helices were predicted by TMHMM (Moller et al. 2001); and CRISPR repeats were searched using CRISPRFinder (Grissa et al. 2007).

Comparative genomics

The draft genome sequence of A. johnsonii MB44 (GenBank accession no. LBMO00000000.1) was compared with the available complete genome of A. baumannii AB307-0294 (GenBank: NC_011595.1) and A. pittii ANC4052 (GenBank: APQO00000000.1). A web server, named OrthoVenn (Wang et al. 2015), was adopted to identify orthologous clusters among the genomes of these species. The function of each orthologous cluster was deduced by BLASTP (Altschul et al. 1997) analysis against UniProt databases. A Venn diagram was created using the web application Venny (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/) with the orthologous cluster ID list. The average nucleotide identity among these species was calculated by the ANI (average nucleotide identity) calculator (Goris et al. 2007).

Data deposition

This whole-genome shotgun project was deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession LBMO00000000. The version described in this paper is version LBMO01000000.

Results and discussion

Microbial features, classification, and nematode toxicity bioassay of MB44

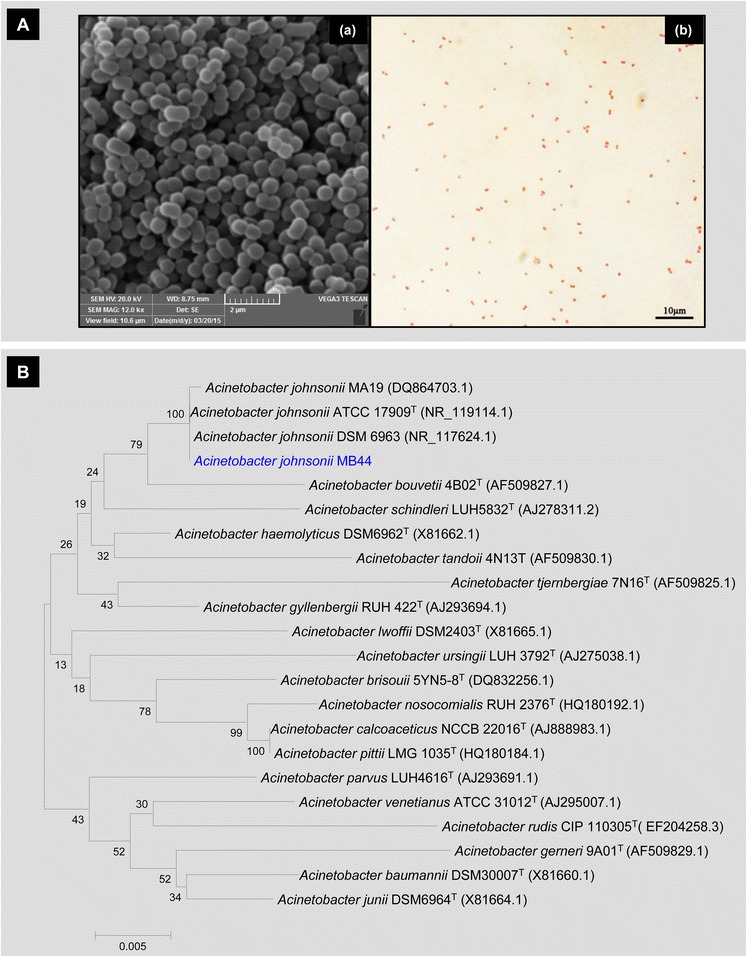

Acinetobacter johnsonii MB44 is a Gram-negative, non-sporulating, short, rod-shaped cells of 1.5–2.5 μm in length and 0.9–1.6 μm in width (Fig. 1A). MB44 cells are nonmotile and aerobic. The Kligler iron agar, nitrate reduction, oxidase reaction, and urea hydrolysis tests are negative, but the catalase and citrate utilization tests are positive. The microbe’s optimum growth temperature is 28–30 °C and no growth occurs at 37 °C or above. Lactose and glucose are fermented, but not for xylose. The DNA content (mol%) is 41.37 %. Prior to whole-genome sequencing, a 1434 bp 16S rRNA gene sequence was amplified by PCR using 27F (AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT) then sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene of A. johnsonii MB44 is shown in Fig. 1B. As displayed, 99.65 % sequence identity to the 16S rRNA gene of A. johnsonii ATCC 17909T was visualized.

Fig. 1.

General characteristics of A. johnsonii MB44. A Micrographs of A. johnsonii MB44 cells in the exponential growth phase. (a) Cells under scanning electron microscopy; (b) Gram-stained cells under optical microscopy. B Neighbor-joining tree generated using MEGA 5 on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequences. Bootstrap values are shown as percentages of 1000 replicates when these values are greater than 50 %. The scale bar represents 0.5 % substitution per nucleotide position

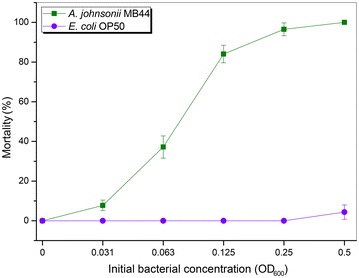

Unexpectedly, A. johnsonii MB44 exhibited remarkable nematicidal activity against C. elegans. As shown in Fig. 2, the MB44 suspension conferred over 80–100 % mortality to C. elegans after 72 h of host–pathogen interaction. This finding suggests the potential virulence of this strain to different animals. The strain could hence serve as a significant model microorganism for studying the fortuitous or potential bacterial pathogens in hospital environment.

Fig. 2.

Bioassay of A. johnsonii cells against C. elegans L4 larva. A. johnsonii MB44 showed evident toxicity to C. elegans by the liquid killing assay. We used the fermentation product of A. johnsonii MB44 to test the strain’s toxicity against L4 nematodes in 96-well plates over six various initial bacterial concentrations (OD600) while comparing with the normal laboratory food E. coli OP50. Error bars represent the standard deviations from mean averages over three independent experiments

General features of the A. johnsonii MB44 genome sequence

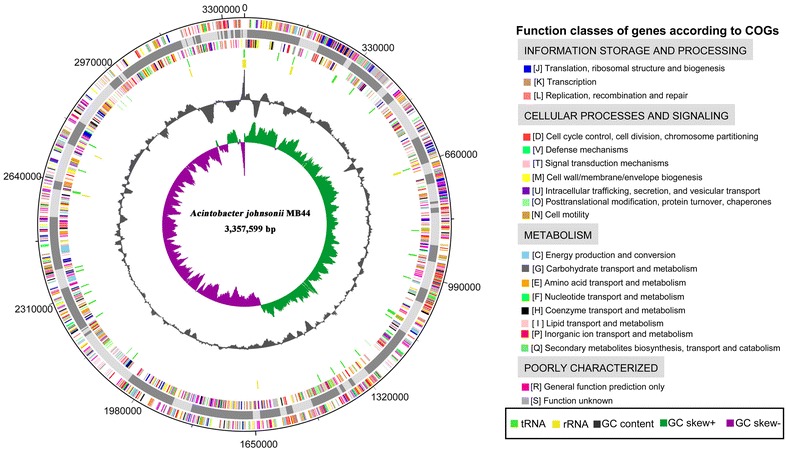

The draft genome sequence consists of a chromosome of 3,357,599 bp in size. Moreover, 5.35 % of the predicted genes encoded signal peptides and 20.93 % of the genes possessed trans-membrane helices. A total of 58.0 % of CDSs could be assigned to the COG database. The distribution of genes into COG functional categories (Table 1; Fig. 3) shows that 39 predicted CDSs were involved in secondary metabolites biosynthesis and transport, such as siderophore synthesis, whereas 30 predicted CDSs were related to defense mechanisms, including several multidrug resistance efflux pumps.

Table 1.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Category | Codea | Value | %Ageb | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information storage and processing | J | 143 | 3.94 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| K | 118 | 3.25 | Transcription | |

| L | 183 | 5.05 | Replication, recombination and repair | |

| Cellular processes and signaling | D | 25 | 0.69 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 30 | 0.83 | Defense mechanisms | |

| T | 68 | 1.88 | Signal transduction mechanisms | |

| M | 156 | 4.30 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis | |

| N | 25 | 0.69 | Cell motility | |

| U | 33 | 0.91 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion | |

| O | 92 | 2.54 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | |

| Metabolism | C | 139 | 3.83 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 73 | 2.01 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | |

| E | 179 | 4.94 | Amino acid transport and metabolism | |

| F | 52 | 1.43 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism | |

| H | 91 | 2.51 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | |

| I | 134 | 3.70 | Lipid transport and metabolism | |

| P | 150 | 4.14 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | |

| Q | 39 | 1.08 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | |

| Poorly characterized | R | 243 | 6.70 | General function prediction only |

| S | 185 | 5.10 | Function unknown |

aFunctional categories are represented according to the codes assigned by NCBI

bThe total is based on the total number of predicted CDSs in the genome

Fig. 3.

Circular representation of the A. johnsonii MB44 chromosome. The reference genome of Acinetobacter lwoffii WJ10621 was used to reorder the contigs of A. johnsonii MB44. The circular map was generated using Artemis. Circles from the center to the outside: GC skew (spring green and purple), GC content (black), rRNA (yellow), tRNA (green), genes on reverse strand colored by COG categories, 75 contigs in alternative grays, genes on forward strand colored by COG categories

Comparative genomics

Acinetobacter baumannii is known as nosocomial pathogen for its ability to cause hospital outbreaks (Dijkshoorn et al. 2007; Peleg et al. 2008). A. pittii has been recently reported for its ability to cause disease in human (Wang et al. 2013). However, A. johnsonii was hardly reported to cause animal or human disease. Comparative genomics between A. baumannii, A. pittii and A. johnsonii will indicate the reason behind different abilities of these three strains to cause nosocomial infections at genome level. The general features of the genome sequence of A. baumannii AB307-0294, A. pittii ANC 4052, and A. johnsonii MB44 are shown in Table 2. The genome size of A. johnsonii MB44 was smaller than those of A. baumannii AB307-0294 and A. pittii ANC 4052. Moreover, the GC content of A. johnsonii MB44 was higher compared with those of A. baumannii AB307-0294 and A. pittii ANC 4052. Previously, ANI value between A. johnsonii MB44 and A. johnsonii ATCC 17909T was calculated and it was found as 95.65 % (Tian et al. 2016). Furthermore, the ANI value between A. johnsonii MB44 and A. baumannii AB307-0294 was 79.72 %, whereas the ANI value between A. johnsonii MB44 and A. johnsonii XBB1 was 95.93 %, A. johnsonii MB44 and A. johnsonii SH046 was 95.81 %. This finding indicates that evolutionary relationship of A. pittii ANC 4052 and A. baumannii AB307-0294 are closer than that of A. johnsonii MB44.

Table 2.

Comparison among the genome characteristics of A. baumannii AB307-0294, A. pittii ANC 4052, and A. johnsonii MB44

| Feature | A. johnsonii MB44 | A. baumannii AB307-0294 | A. pittii ANC 4052 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finishing quality | Draft | Complete | Draft |

| Accession number | LBMO00000000 | NC_011595 | APQO00000000 |

| Origin | Frost plant tissue | Blood | Blood |

| Genome size (bp) | 3,357,599 | 3,760,981 | 3,95,339 |

| G + C Content (mol%) | 41.37 | 39.00 | 38.80 |

| CDSs | 3626 | 3513 | 3766 |

| rRNA genes | 14 | 18 | 18 |

| tRNA genes | 81 | 73 | 74 |

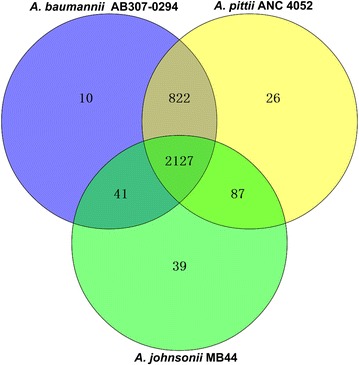

The predicted proteome of A. johnsonii MB44 was assigned into orthologous clusters, along with the proteomes of A. baumannii AB307-0294 and A. pittii ANC 4052 to predict unique and/or shared characteristics among these species. As calculated within OrthoVenn, a total of 2127 putative orthologous proteins were shared among A. baumannii AB307-0294, A. pittii ANC 4052, and A. johnsonii MB44 (Fig. 4). A. baumannii AB307-0294 exhibited more shared orthologous proteins compared with A. johnsonii MB44 and the other two species. A. baumannii and A. pittii are both implicated in serious human infection. Hence, the genes shared by A. baumannii AB307-0294 and A. pittii ANC 4052 but were absent in A. johnsonii MB44 may be relevant in the two former species’ s ability to cause nosocomial infection.

Fig. 4.

Visualization of the OrthoVenn output comparing the number of unique and/or shared orthologs of A. baumannii AB307-0294, A. pittii ANC 4052, and A. johnsonii MB44

Genes predicted virulent to C. elegans

To predict the virulent proteins in the genomic data of A. johnsonii MB44, a software named MP3 (Gupta et al. 2014) was used to analyze the pathogenicity and comprehend the mechanism of pathogenesis by a hybrid Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Hidden Markov Model (HMM) approach. A total of 108 proteins of A. johnsonii MB44, with consistent predictions from both HMM and SVM, were classified as nematode-pathogenic (Additional file 1: Table S1). These putative virulent proteins were divided into four groups on the basis of mechanism of pathogenesis, particularly, structure/adhesion/colonization, invasion, secretion, and resistance (Roth 1988; Wu et al. 2008) (Table 3). Genes involved in the biosynthesis of fimbriae, LPS (lipopolysaccharide), porin, membrane protein, and phospholipase may promote pathogen adherence and invasion of host cells. These genes associated with Types I and II secretion systems may assist the transport of toxin. Transporters classified under the ATP-binding cassette superfamily, resistance–nodulation–division family, and major facilitator superfamily, which are associated with multidrug efflux pumps, may play important roles in antimicrobial resistance.

Table 3.

Prediction of pathogenic proteins in A. johnsonii MB44 using MP3

| Classification | Subclassification | Pathogenic proteins (HS)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure/adhesion/colonization | Fimbriae | AAU60_14105 | AAU60_12470 | AAU60_14060 |

| AAU60_14040 | AAU60_14030 | AAU60_13085 | ||

| AAU60_14155 | AAU60_14035 | |||

| LPS | AAU60_08620 | |||

| Porin | AAU60_04175 | AAU60_08060 | ||

| Membrane protein | AAU60_03545 | AAU60_00920 | AAU60_00205 | |

| AAU60_00470 | AAU60_06630 | AAU60_09350 | ||

| AAU60_01560 | AAU60_04550 | AAU60_13935 | ||

| AAU60_12465 | AAU60_06330 | |||

| Invasion | Phospholipase | AAU60_09055 | AAU60_12925 | |

| Secretion | Type I secretion system | AAU60_04920 | AAU60_04935 | AAU60_13170 |

| Type II secretion system | AAU60_10120 | AAU60_01405 | AAU60_08540 | |

| AAU60_10125 | AAU60_01400 | AAU60_08535 | ||

| ABC transporter | AAU60_06635 | AAU60_00105 | AAU60_07820 | |

| AAU60_10860 | AAU60_10765 | AAU60_05600 | ||

| AAU60_04745 | AAU60_09575 | AAU60_15185 | ||

| AAU60_14255 | AAU60_15880 | AAU60_10855 | ||

| RND transporter | AAU60_15305 | AAU60_13180 | AAU60_06585 | |

| MFS transporter | AAU60_15825 | AAU60_07305 | AAU60_08870 | |

| AAU60_07850 | AAU60_07470 | AAU60_15415 | ||

| Resistance | Drug/multi-drug resistance | AAU60_03375 | AAU60_03380 | AAU60_01105 |

| AAU60_00855 | ||||

aHS: predictions from both HMM (hidden markov model) and SVM (hybrid support vector machines) modules are in consensus

Acinetobacter baumannii is the most prevalent nosocomial pathogen of the genus Acinetobacter; thus, several recently identified virulence factors in A. baumannii (Cerqueira and Peleg 2011) have been found as homologous proteins in A. johnsonii MB44 (Table 4). Due to its known virulence factors against animal cells, A. baumannii was used as reference species for the prediction of nematicidal genes of MB44. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) is a key virulence factor of A. baumannii, which localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells (Choi et al. 2005). Previous investigations revealed that OmpA can localize to the nucleus of eukaryotic cells and induce cytotoxicity (Choi et al. 2008a, b). The outer membrane protein (AAU60_12465) in A. johnsonii MB44 shared a 89 % amino acid sequence similarity with OmpA of A. baumannii ATCC 19606, inferring the former’s potential as a virulent protein. Moreover, phospholipase D (PLD) was demonstrated in A. baumannii to participate in the growth in human serum and epithelial cell invasion (Jacobs et al. 2010). Penicillin-binding protein 7/8 (PBP-7/8) is important for the survival of A. baumannii in a rat-soft-tissue infection model (Russo et al. 2009). The predicted phospholipase (AAU60_07280, AAU60_12565) and penicillin-binding protein in A. johnsonii MB44 (AAU60_01255) exhibited a high similarity to PLD and PBP-7/8. We therefore speculate that these genes may function as important virulence factors in A. johnsonii MB44.

Table 4.

Potential virulent proteins in A. johnsonii MB44 and known homologous A. baumannii virulent proteins

| Protein function | Gene accession number | Major motif | Virulent protein | Microorganism | Amino acid similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin-binding protein 7/8 | AAU60_01255 | Transpeptidase superfamily | PBP-7/8 | A. baumannii strain 307-0294 | 82 |

| Phospholipase D | AAU60_07280 | PLDc_SF superfamily | PLD | A. baumannii strain 98-37-09 | 62 |

| AAU60_12565 | PLDc_SF superfamily | PLD | A. baumannii strain 98-37-09 | 85 | |

| Outer membrane protein A | AAU60_12465 | OmpA_C-like superfamily | OmpA | A. baumannii ATCC 19606 | 89 |

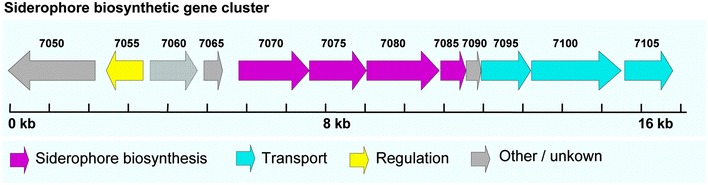

Putative genes involved in siderophore biosynthesis and transport

Recent studies demonstrated that iron acquisition systems are important virulence factors in some pathogenic bacteria; such pathogens employed siderophores to acquire growth-essential iron from the host (Schaible and Kaufmann 2004; Weinberg 2009). The iron-binding siderophore produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is found to be a key virulence factor in disrupting mitochondrial and iron homeostasis in C. elegans (Kirienko et al. 2015). The ability to synthesize siderophores was believed to potentially affect the virulence of A. johnsonii MB44 against C. elegans. In the draft genome of A. johnsonii MB44, four secondary metabolite gene clusters were found using the antiSMASH pipeline (Weber et al. 2015), including one siderophore cluster (AAU60_07050–AAU60_07105). The siderophore gene cluster (Fig. 5) consists of 16,761 bp of nucleotide sequence, putatively containing four siderophore biosynthesis genes (AAU60_07070–AAU60_07085). Protein products of these four genes show high identity (63–79 %) to a recognized siderophore gene cluster of A. haemolyticus ATCC 17906T (Funahashi et al. 2013). In the putative siderophore cluster of A. johnsonii MB44, three genes (AAU60_7095–AAU60_7105) were involved in the transport of siderophore. AAU60_7100 encodes a TonB-dependent siderophore receptor. The products of AAU60_7095 and AAU60_7105, which belong to the major facilitator superfamily of proteins, act as siderophore transporter and exporter, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Gene organization of the putative siderophore biosynthesis gene cluster found in A. johnsonii MB44 genome. The putative 16.76 kb gene cluster carries 12 open reading frames (AAU60_07070–AAU60_07085). The proteins encoded by siderophore biosynthesis genes (colored magenta) of the siderophore biosynthetic gene cluster showing high identity (63–79 %) to an identified siderophore gene cluster of A. haemolyticus ATCC 17906T

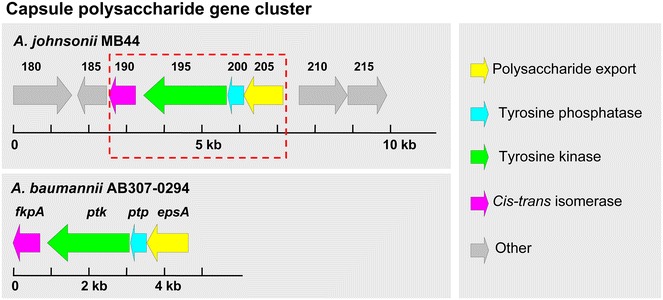

Capsular polysaccharide gene cluster

Capsules are important virulence factors that enable pathogenic bacteria to avoid the host defense mechanisms by their antiphagocytic ability (Heumann and Roger 2002). The K1 capsular polysaccharide from A. baumannii AB307-0294 has been demonstrated in a rat-soft-tissue infection model as a major virulence factor (Russo et al. 2010). The capsular cluster of A. baumannii AB307-0294 consists of 10 kb of sequence containing four genes (fkpA, ptk, ptp, and epsA), facilitating the polymerization and transport of capsular polysaccharide. These genes were aligned against the genome sequence of A. johnsonii MB44 with BLAST. Subsequently, four genes (AAU60_00190–AAU60_00205), with amino-acid sequences exhibiting high similarity (78–80 %) to the capsular gene cluster of A. baumannii AB307-0294, were found to constitute the capsular cluster of A. johnsonii MB44 (Fig. 6; Table 5). Therefore, these four genes were putatively involved in capsular polysaccharide polymerization and transport of A. johnsonii MB44. Prior studies suggested that insertions in genes involved in the capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis of Staphylococcusaureus reduce C. elegans deaths (Bae et al. 2004). Accordingly, we speculate that capsular polysaccharide may be a virulence factor of A. johnsonii MB44 involved in C. elegans lethal infection.

Fig. 6.

Genetic organization and conservation of the capsule polysaccharide cluster found in the A. johnsonii MB44 genome. The capsular cluster of A. johnsonii MB44 consists of four open reading frames (AAU60_00190–AAU60_00250). The identified capsular cluster of A. baumannii AB307-0294 is shown for comparison. The proteins encoded by the capsular cluster shown in the red dashed border exhibit high similarity (78–80 %) to the capsular gene cluster of A. baumannii AB307-0294

Table 5.

Summary of homology searches for the open reading frames found in the putative capsule cluster of A. johnsonii MB44

| ORF (aa) (A. johnsonii MB44) | Homologous protein (aa) (A. baumannii AB307-0294) | Identity/similarity (%) (aa overlap) | Function predicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAU60_00190 (234) | FkpA (240) | 66/78 (242) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase |

| AAU60_00195 (731) | Ptp (727) | 65/80 (714) | Protein tyrosine kinase |

| AAU60_00200 (142) | Ptp (142) | 64/80 | Tyrosine phosphatase |

| AAU60_00205 (344) | EpsA (366) | 63/79 | Polysaccharide export outer membrane protein |

Conclusions

In this study, we presented a whole-genome analysis of A. johnsonii MB44 to identify its potential virulence factors against C. elegans. The MB44 genome contained 108 virulent proteins predicted by MP3, and four proteins showed high identity to the known virulent proteins in the pathogenic A. baumannii. Furthermore, one siderophore biosynthesis gene cluster and one capsular polysaccharide gene cluster were identified, which were relevant to nematicidal activity of pathogenic bacteria. The current study demonstrated that A. johnsonii, which was generally recognized as a nonpathogenic bacterium, could be an opportunistic pathogen to animals.

Authors’ contributions

ST performed most of the experiments, made most of the data evaluation and drafted parts of the manuscript. MA and LX participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. LL conceived and directed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, Grant 2013CB127504) and grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31570123 and 31270158).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional file

10.1186/s40064-016-2668-5 The predicted nematode-virulent genes in A johnsonii genome.

Contributor Information

Shijing Tian, Email: lilin@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Muhammad Ali, Email: lilin@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Li Xie, Email: lilin@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Lin Li, Phone: +86-27-8728 6952, Email: lilin@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae T, Banger AK, Wallace A, Glass EM, Aslund F, Schneewind O, Missiakas DM. Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes identified by bursa aurealis mutagenesis and nematode killing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12312–12317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404728101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D30–D35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergogne-Berezin E, Towner KJ. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:148–165. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira GM, Peleg AY. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenicity. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:1055–1060. doi: 10.1002/iub.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, et al. Outer membrane protein 38 of Acinetobacter baumannii localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1127–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A targets the nucleus and induces cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:309–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, Lee JS, Lee YC, Park TI, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii invades epithelial cells and outer membrane protein A mediates interactions with epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Sheng WH, Li SY, Lin YC, Wang JT, Chen YC, Chang SC. Influence of genospecies of Acinetobacter baumannii complex on clinical outcomes of patients with Acinetobacter bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:352–360. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:939–951. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi T, Tanabe T, Maki J, Miyamoto K, Tsujibo H, Yamamoto S. Identification and characterization of a cluster of genes involved in biosynthesis and transport of acinetoferrin, a siderophore produced by Acinetobacter haemolyticus ATCC 17906T. Microbiology. 2013;159:678–690. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.065177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Tiedje JM. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W52–W57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Kapil R, Dhakan DB, Sharma VK. MP3: a software tool for the prediction of pathogenic proteins in genomic and metagenomic data. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heumann D, Roger T. Initial responses to endotoxins and Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;323:59–72. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, et al. Whole-genome sequence of a multidrug-resistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter lwoffii. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5549–5550. doi: 10.1128/JB.05617-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs AC, et al. Inactivation of phospholipase D diminishes Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1952–1962. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00889-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirienko NV, Ausubel FM, Ruvkun G. Mitophagy confers resistance to siderophore-mediated killing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1821–1826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424954112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, et al. Molecular characterization of an ice nucleation protein variant (inaQ) from Pseudomonas syringae and the analysis of its transmembrane transport activity in Escherichia coli. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1097–1108. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller S, Croning MD, Apweiler R. Evaluation of methods for the prediction of membrane spanning regions. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:646–653. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.7.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA. Virulence mechanisms of bacterial pathogens. Washington: American Society for Microbiology; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Russo TA, et al. Penicillin-binding protein 7/8 contributes to the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:513–521. doi: 10.1086/596317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo TA, et al. The K1 capsular polysaccharide of Acinetobacter baumannii strain 307-0294 is a major virulence factor. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3993–4000. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00366-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. Iron and microbial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:946–953. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJ, Birol I. ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 2009;19:1117–1123. doi: 10.1101/gr.089532.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MG, Des Etages SG, Snyder M. Microbial synergy via an ethanol-triggered pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3874–3884. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3874-3884.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Ali M, Xie L, Li L. Draft genome sequence of Acinetobacter johnsonii MB44, exhibiting nematicidal activity against Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e01772–15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01772-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Farres X, et al. Loss of LPS is involved in the virulence and resistance to colistin of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter nosocomialis mutants selected in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2981–2986. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen T, Yu R, Lu X, Zong Z. Acinetobacter pittii and Acinetobacter nosocomialis among clinical isolates of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex in Sichuan, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76:392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Coleman-Derr D, Chen G, Gu YQ. OrthoVenn: a web server for genome wide comparison and annotation of orthologous clusters across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W78–W84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, et al. antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg ED. Iron availability and infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HJ, Wang AH, Jennings MP. Discovery of virulence factors of pathogenic bacteria. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong Z. The complex genetic context of blaPER-1 flanked by miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements in Acinetobacter johnsonii. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]