Abstract

Objectives

Measurement of soil contamination levels has been considered a feasible method for dose estimation of internal radiation exposure following the Chernobyl disaster by means of aggregate transfer factors; however, it is still unclear whether the estimation of internal contamination based on soil contamination levels is universally valid or incident specific.

Methods

To address this issue, we evaluated relationships between in vivo and soil cesium-137 (Cs-137) contamination using data on internal contamination levels among Minamisoma (10–40 km north from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant), Fukushima residents 2–3 years following the disaster, and constructed three models for statistical analysis based on continuous and categorical (equal intervals and quantiles) soil contamination levels.

Results

A total of 7987 people with a mean age of 55.4 years underwent screening of in vivo Cs-137 whole-body counting. A statistically significant association was noted between internal and continuous Cs-137 soil contamination levels (model 1, p value <0.001), although the association was slight (relative risk (RR): 1.03 per 10 kBq/m2 increase in soil contamination). Analysis of categorical soil contamination levels showed statistical (but not clinical) significance only in relatively higher soil contamination levels (model 2: Cs-137 levels above 100 kBq/m2 compared to those <25 kBq/m2, RR=1.75, p value <0.01; model 3: levels above 63 kBq/m2 compared to those <11 kBq/m2, RR=1.45, p value <0.05).

Conclusions

Low levels of internal and soil contamination were not associated, and only loose/small associations were observed in areas with slightly higher levels of soil contamination in Fukushima, representing a clear difference from the strong associations found in post-disaster Chernobyl. These results indicate that soil contamination levels generally do not contribute to the internal contamination of residents in Fukushima; thus, individual measurements are essential for the precise evaluation of chronic internal radiation contamination.

Keywords: internal radiation exposure, whole body counter, transfer factor, countermeasure, Cs-134, Cs-137

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We undertook the first study after Japan's 2011 Fukushima nuclear incident to clarify whether soil contamination levels are useful for estimating internal contamination levels among residents living in radio-contaminated areas.

We used the data in Minamisoma city, which had soil contamination levels equivalent to those of Zone III in Chernobyl, where the local government offered the internal radiation screening programme free of charge to all residents.

Whole body counter screenings were voluntary, and this study is limited to data from Minamisoma, and it is unclear whether these results are generalisable to other towns or villages.

Introduction

Radiation exposure can generate long-term health risks, including tumours.1 2 Cumulative radiation exposure is a serious public concern among residents in areas contaminated by radiation after nuclear accidents.3 Chronic internal radiation exposure accounts for a substantial fraction of long-term cumulative radiation exposure among residents due to sustained contamination of locally grown produce, as was the case after the Chernobyl disaster;4 thus, precise evaluation of chronic internal contamination among residents is of great importance for providing accurate and effective countermeasures.5

However, carrying out individual evaluations requires substantial human and material costs in addition to time; this type of evaluation is often impossible due to lack of measurement devices, consent or interest in screening services.6 In these situations, assessment of food and soil contamination levels is often the only feasible method for estimating levels of internal contamination.7 While internal contamination can be estimated through pathways such as food, water and air, a strong correlation has been reported between soil and internal contamination levels, and the use of soil contamination as an internal contamination marker was recommended as a simple and effective method after the Chernobyl disaster.8 In 1996, 10 years after the Chernobyl disaster, the Ukraine was divided into zones based on the levels of soil contamination, with Zone I representing the highest level of contamination (Cesium-137: Cs-137 deposition density >1480 kBq/m2). Residents living in Zone II (555–1480 kBq/m2) have higher levels of internal contamination than those living in Zone III or Zone IV (185–555 kBq/m2 and 37–555 kBq/m2, respectively) and these conditions have persisted even 25 years after the disaster.9

The efficacy of this estimation method has been assessed using a transfer coefficient to estimate the degree to which radioactive substances transfer from soil to growing food,10 and subsequently estimating the internal contamination levels of residents in each area by modelling the intake of these foods, as described by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR).8 Several researches post-Chernobyl disaster addressed the relationship of radionuclide soil contamination to the human’s internal contamination, and showed the difficulty in assuming a predictable relationship between them.11–15 However, there has been no study that evaluates if this soil contamination-based estimation method for internal contamination levels is an appropriate approach in the context of the Fukushima disaster.

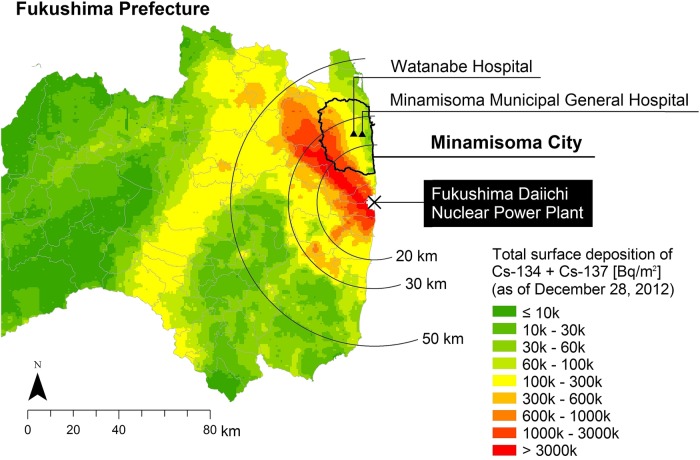

After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident on 11 March 2011,16 a number of radiation measurements were performed, including soil contamination and individual whole body counter (WBC) screenings.17 Minamisoma city is located 10–40 km from the power plant, with part of the city falling under the mandatory exclusion zone,18 and has offered WBC internal radiation exposure screenings free of charge to all residents since July 201119 (figure 1). According to measurements made 2 months after the accident (April 2011), over half of Minamisoma city, where many people continue to live, had soil contamination levels equivalent to those of Zone III in Chernobyl.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Minamisoma city on the base map of radiocesium deposition distribution as of 28 December 2012 (the data source of radiocesium deposition levels is described in the ‘Home soil contamination levels’ section).

To clarify whether soil contamination levels are similarly useful for estimating internal contamination levels following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident, this study assessed the relationship between chronic internal and soil contamination, and evaluated the efficacy of using soil contamination as a marker for internal contamination based on the results of continuous internal radiation exposure monitoring in Minamisoma city.

Materials and methods

In order to assess the possible associations between soil and internal contamination levels in Minamisoma residents, data on internal contamination levels were accessed through the records of WBC screenings that took place 2–3 years following the accident (12 March 2013 to 11 March 2014). Age, sex, weight, levels of internal Cs-137 contamination, date of screening, residential address, and dietary intakes and behaviours (avoiding products from Fukushima or not) were ascertained for all screening participants based on responses to questionnaires administered at the time of the screenings. Soil contamination as of the day of screening was calculated using data on each patient's residential address.

The excretion of Cs is faster in children compared to adults, and as internal contamination levels of Cs have been marginal, with almost no internal contamination detected in children in Minamisoma,20 it was impossible to accurately assess associations between soil contamination and internal contamination in children. For this reason, the present study only included WBC screening participants aged 16 years and older.

WBC screening in Minamisoma city

Since July 2011, the free WBC screenings in Minamisoma city have targeted all Minamisoma residents.19 Those who wish may undergo screenings once a year. Information on screenings is distributed by the local government and publicised in magazines. These screenings take place at two hospitals in the city that host permanent WBC systems. The WBC machine in Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital is a stereoscopic machine with two 3×5×16 inch NaI scintillation detectors (Fastscan Model 2251; Canberra, Inc, Meriden, Connecticut, USA). A 30 cm stool was used for residents below 130 cm in height. The WBC device in Watanabe Hospital is in the shape of a chair and has two 3×5×16 inch NaI scintillation detectors (WBC-R43-22458; Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd, Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan). The detection limits of both machines are 220 Bq/body for Cs-134 and 250 Bq/body for Cs-137 following a 2 min scan. Calibration was performed on the basis of recommendations from the respective companies.

Home soil contamination levels

Data were collected from the official website of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).21 After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, MEXT has conducted repeated airborne monitoring within an 80 km zone from the nuclear power plant. Monitoring is performed 300 m above the ground, with a track width of about 1.85 km, and estimates the deposition of radioactive substances on the ground surface based on the air dose rate 1 m above the ground surface The recorded data are the average of the measured values within circles 600 m in diameter at ground level. The data contain the Cs (Cs−134+Cs−137) deposition levels (Bq/m2) and the latitude and longitude coordinates of their monitoring points.

The soil contamination levels at each participant household were calculated as follows. First, since the most recent soil contamination data were measured in 2012, and therefore did not match the study period (12 March 2013 to 11 March 2014), a time extrapolation method was applied to estimate the soil contamination levels on the date of WBC measurement. We considered two MEXT monitoring results in 2012: the fifth monitoring performed between 22 and 26 June 2012, and the sixth monitoring between 31 October and 16 November 2012.

Second, the MEXT monitoring results were averaged by a 500-m2 mesh on the basis of the Japan Profile for Geographical Information Standards (elevation and slope angle fourth mesh data), developed by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport in Japan, so that each participant's home was assigned to one of the mesh areas. This approach enabled us to estimate soil contamination levels at each participant’s home on the date of their WBC measurements.

Food choices/behaviours

A self-reported dietary preference assessment questionnaire was administered to the participants at the time of their WBC screening. This questionnaire contained items on food and water consumption. The food-related items asked whether the respondents selected certain supermarket produce (fish, meat, rice, vegetable/fruits, mushroom and milk) based on their origin (Fukushima vs non-Fukushima), or whether they shopped at local farms. The water-related questions asked whether the respondents avoided drinking tap water.

Analysis

We used Tobit regression analysis to evaluate the relationship between internal and soil contamination after adjusting for potential covariates. Since WBC measurement has a limited detection capability, the levels of internal contamination in a large number of screening participants fell below the detection threshold, resulting in zero measurement values. Tobit regression is an appropriate analysis method that adjusts standard linear regression models for left-censoring effects such as those observed with WBCs. Justification for the use of Tobit regression analysis in the context of WBC measurements post-Fukushima disaster can be found elsewhere.22 23 Since a small number of outliers in terms of internal contamination levels were expected in the screening programme, the natural logarithm of the measurement value (ie, the body burden of Cs-137 concentration (Bq/body)) was employed as the dependent variable in the models. Accordingly, the regression coefficients for each of the independent variables were computed on a logarithmic scale; we therefore used the exponentiated forms of the coefficients in the regression results to indicate the multiplicative change in Cs-137 contamination levels for a per-unit increase in the variables, which is presented as ‘relative risk (RR)’ in the resulting table. In addition, in order to support clinical and policy interpretations, we considered body concentration (Bq/kg) rather than body burden (Bq/body) as an outcome measure by adding the natural logarithm of weight as an offset variable to the independent variables. The offset restricts the coefficient of weight to a value of 1, which theoretically enabled us to move weight to the left side of the equation in order to transform body burden into body concentration.22 23

The confounding variables considered during analysis were age, sex, height, dwelling location (Minamisoma city or different places within or out of the Fukushima Prefecture), date of screening and season of the examination (spring, summer, autumn or winter). All of these variables were included as covariates in the models and tested for multicollinearity using partial F tests. Although our data set contained the results of the food choices/behaviour assessments (ie, participant foodstuff procurement preferences for supermarket or locally grown produce) because only a small proportion of participants reported consuming locally grown products, it was difficult to construct stable multivariate regression models; we therefore did not consider these assessments in the regression analyses.

Since some uncertainty might exist regarding the soil contamination levels, we conducted sensitivity analyses by constructing regression models where the levels of soil contamination were analysed in two types of categorical forms—equal intervals and quantiles; that is, we made the three regression models as described below:

Model 1: soil contamination in continuous form;

Model 2: soil contamination in categorical forms with equal intervals;

Model 3: soil contamination in categorical forms with quantiles.

Equal interval means that the range of values (ie, soil contamination levels in this study) is divided into the specified number of classes, with each interval having the same width. Quantiles are a set of cut-off points that divide the population into equally sized classes. Geospatial processing of data was conducted using ArcGIS V.10.2 and all statistical analyses were performed using STATA/MP V.13.

Results

In the second year after the accident (12 March 2013–31 March 2014), 7987 people underwent internal radiation screening, more than 90% of whom were living in Minamisoma city (table 1). Each individual underwent WBC screening only once over the surveyed time. Their mean age was 55.4 years (range: 16–95 years), and 4560 (57.1%) were female. Internal contamination was detected in 145 participants (1.8%). Among these participants with detectable levels of Cs-137, the mean body burden and concentrations were 558.6 Bq/body (range: 252–16 810 Bq/body) and 9.0 Bq/kg (range: 3.0–247.2 Bq/kg), respectively. The proportion of people consuming locally grown produce was low, at 12.6% for rice and 25.8% for vegetable/fruits, and extremely low for fish, meat, mushrooms and milk, at 2.1–3.4%, depending on produce type. There was no statistical relationship between Cs soil contamination and the proportion of those who avoided Fukushima produce (table 2), and few people consumed locally grown produce without radiation inspection certificates (0.1–6.1%, depending on produce type).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (n=7987)

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 55.4 (18.4) |

| Gender (N, %) | |

| Male | 3427 (42.9) |

| Female | 4560 (57.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean, SD) | 23.8 (3.8) |

| Dwelling site (N, %) | |

| Minamisoma city | 7236 (90.6) |

| Inside Fukushima | 525 (6.6) |

| Outside Fukushima | 226 (2.8) |

| Internal contamination (N, % of those detected) | 145 (1.8) |

| Product purchase pattern (N, % of those who considered the geographical origin of products) | |

| Fish | 2388 (29.9) |

| Meat | 2828 (35.4) |

| Rice | 2321 (29.1) |

| Vegetable/fruits | 3746 (46.9) |

| Mushrooms | 2138 (26.8) |

| Milk | 3024 (37.9) |

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

χ2 Test results from cross tabulation of the percentage of participants who considered the geographical origin of products and radiocesium deposition level at the dwelling location

| Radiocesium deposition (kBq/m2) |

p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >25 | (25–50) | (50–75) | (75–100) | 100< | ||

| Product type | ||||||

| Fish | 69.8 | 70.3 | 70.4 | 69.3 | 71.8 | 0.91 |

| Meat | 63.8 | 64.8 | 66.1 | 63.0 | 67.5 | 0.33 |

| Rice | 70.0 | 71.6 | 72.1 | 70.4 | 71.8 | 0.59 |

| Vegetable/fruits | 53.3 | 52.7 | 54.2 | 54.0 | 49.0 | 0.44 |

| Mushrooms | 72.9 | 74.0 | 73.8 | 71.7 | 72.2 | 0.70 |

| Milk | 60.5 | 62.9 | 64.5 | 63.1 | 61.7 | 0.10 |

Table 3 presents the associations between internal and soil Cs-137 contamination levels. Models 1, 2 and 3 considered soil contamination as continuous and categorical (equal intervals and quantiles) values, respectively. Classification of soil contamination levels in models 2 and 3 was performed on five classes, which is the maximum number of groups, where each class had sufficient numbers of participants to produce stable models. No problematic correlations between covariates were detected in any model.

Table 3.

Tobit regression models for the relationship between Cs-137 level (bq/kg) and covariates

| Variables | Relative risk (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Radiocesium deposition (10 kbq/m2)† | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05)* | ||

| Class 1 | – | Ref. | Ref. |

| Class 2 | – | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.71) | 1.00 (0.69 to 1.46) |

| Class 3 | – | 1.11 (0.81 to 1.52) | 1.29 (0.90 to 1.85) |

| Class 4 | – | 1.20 (0.83 to 1.75) | 1.39 (0.98 to 1.97) |

| Class 5 | – | 1.73 (1.19 to 2.53)** | 1.47 (1.04 to 2.07)* |

| Age (years) | |||

| (16–40) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| (40–65) | 1.44 (0.97 to 2.14) | 1.44 (0.97 to 2.13) | 1.44 (0.97 to 2.12) |

| 65– | 2.20 (1.45 to 3.33)*** | 2.20 (1.45 to 3.34)*** | 2.17 (1.44 to 3.29)*** |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 0.52 (0.39 to 0.71)*** | 0.52 (0.39 to 0.71)*** | 0.53 (0.39 to 0.71)*** |

| Height (cm) | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00)* | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00)* | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00)* |

| Location | |||

| Minamisoma city | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Inside Fukushima | 0.89 (0.58 to 1.38) | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.37) | 0.92 (0.60 to 1.43) |

| Outside Fukushima | 0.70 (0.28 to 1.76) | 0.75 (0.29 to 1.90) | 0.79 (0.31 to 2.03) |

| Examination date | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00)** | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00)** | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00)** |

| Season of examination | |||

| Spring | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Summer | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.85)** | 0.66 (0.51 to 0.84)** | 0.67 (0.52 to 0.86)** |

| Autumn | 1.25 (0.89 to 1.76) | 1.25 (0.89 to 1.76) | 1.27 (0.90 to 1.79) |

| Winter | 1.31 (0.82 to 2.09) | 1.31 (0.82 to 2.09) | 1.33 (0.83 to 2.12) |

*<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001.

†Classes 1–5 indicate (0–2.5), (2.5–5.0), (5.0–7.5), (7.5–10.0) and 10.0–, respectively, for model 2, and (0–1.1), (1.1–2.8), (2.8–4.3), (4.3–6.3) and 6.3–, respectively, for model 3.

We identified a statistically significant association between internal and continuous soil Cs-137 contamination levels (model 1, p value <0.001), although there was only a slight association (RR: 1.03 per 10 kBq/m2 increase in soil contamination, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05). Analysis of categorical soil contamination levels revealed statistical (but not clinical) significance only in relatively higher soil contamination levels, with RR of Cs-137 levels above 100 kBq/m2 compared to those below 25 kBq/m2 of 1.75 and 95% CI of 1.20 to 2.54 (model 2, p value <0.01) and above 63 kBq/m2 compared to those below 11 kBq/m2 of 1.45 and 95% CI of 1.03 to 2.05 (model 3, p value <0.05). These results indicate a statistically significant relationship between the internal and soil Cs-137 contamination levels; however, the effect of living in areas with relatively lower soil contamination levels (in terms of the equal interval/quantile classifications in the context of Minamisoma city) on internal Cs-137 contamination levels may be so low that it was undetectable in this study. Since model 1–3 showed similar results for the regression estimates on the soil contamination, the uncertainty in the soil contamination data might be marginal.

In addition to soil contamination levels, several other covariates were associated with internal Cs-137 levels (table 3). For example, the older age group (over 65 years) had significantly higher internal contamination than the younger age group (16–40 years), with RR ranging from 2.17 to 2.20 depending on the models. Internal contamination levels in women were half those in men, with RR ranging from 0.52 to 0.53 depending on the models. Internal contamination levels in summer were lower than those in spring, with RR ranging from 0.66 to 0.67 depending on the models. Dwelling locations were not significantly associated with internal Cs-137 contamination levels. Given the small CIs (or SE) of each covariate for the regression estimates, the uncertainty in the WBC data used in this study might be small.

Discussion

Some previous studies in the context of the Chernobyl disaster demonstrated difficulty in estimating the levels of internal contamination based on radionuclide deposition or soil contamination.12 24 25 This study supports their findings in the case of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident.

This study revealed that internal and soil contamination were not associated at low levels, and only loose/small associations were observed in areas with slightly higher levels of soil contamination. These results indicate that soil contamination levels generally do not contribute to the internal contamination of residents in this area, representing a clear difference from the strong associations found in post-disaster Chernobyl, where residents had no choice but to consume local produce, regardless of its potential contamination level.

Several reasons could be raised for this difference. First, regardless of soil contamination levels, the majority of participants consumed foodstuffs that had undergone scrupulous control before reaching the market in Fukushima. This study showed that the proportions of residents consuming produce in supermarkets or locally grown produce with radiation inspection certificates were overwhelmingly large (93.9–99.9%, depending on produce type, which is comparable to those in our previous study).20 Since the first few weeks after the disaster, food products have undergone strict contamination screening before distribution and previous research has reported extremely low contamination levels in products originating within and outside the Fukushima Prefecture.16 A primary cause of internal contamination is consumption of contaminated food products; however, in situations where the available foods are thoroughly screened, internal contamination levels may be low even in residents living in highly contaminated areas.

Second, previous research has found high levels of internal contamination to be associated with continued consumption of particular foods, such as mushrooms, mountain vegetables and wild game, which are locally grown and consumed outside of the market and without radiation inspection. In this study, few participants reported consuming home-grown food products and the lack of difference in consumption patterns by area may partially explain the limited association between soil contamination and internal contamination levels. However, individuals continuously consuming foods outside of market control may have high levels of internal contamination. Individual assessment of internal radiation remains important in order to identify these people. Third, there is a geographical, social and cultural difference such as food habits, including consumption of forest products, between Japan and the Chernobyl disaster-stricken inland areas in Europe. In societies such as Fukushima, with highly developed food markets and freedom for residents to move as they wish, control of food products released to the market is highly important. With successful food control, the soil contamination levels in the areas in which the residents are living may not affect their internal contamination levels.26 27

It is to be noted that several covariates including age, sex and seasons of examinations were associated with high internal Cs-137 levels. While the older aged group showed significantly higher levels of internal Cs-137 than the younger aged group, this finding is presumably because the rates of Cs metabolism in body and renal Cs excretion show a decrease with age. The seasonal changes in the levels of internal Cs-137 were assumed to be due to the changes in consumption of contaminated locally grown produce such as mushroom and mountain vegetables during harvesting, as was shown in previous studies in Chernobyl.24

Caution is necessary in interpreting the slight association between soil and internal contamination in areas with comparatively high soil contamination. The reason for this finding is not clear but may be related to occupational or lifestyle differences between residents or areas. With a larger number of participants, it is possible that an association between soil contamination and internal contamination could have been found in areas with lower soil contamination levels. However, this study suggests that soil contamination might have little to no impact on the internal contamination among residents. Control of market foods may make it possible to control levels of internal radiation, even among residents inhabiting areas with highly contaminated soil.

When comparing similar levels of soil contamination, it should be noted that there are extreme differences between internal radiation in residents of areas around Chernobyl and those in Fukushima.28 This may be influenced by Fukushima's lower levels of radiation transfer coefficients from soil to plants,29–31 countermeasures such as food screening policies and decontamination efforts, greater freedom around choice of food products and increased availability of foods from outside Fukushima.32 33 However, identification of the contributory factors is outside the scope of this study and warrants further research. Nevertheless, it appears that soil contamination may not always be an effective marker of internal contamination in Fukushima.

This study has several limitations. First, the WBC screenings were voluntary, which may have led to over-screening of those particularly cautious in regard to radiation protection or under-screening of those who have fears of being detected and having to undergo pressures to change their dietary behaviour, and underestimation of the actual levels of internal contamination. Contrarily, those with high levels of internal contamination may seek screening for fear of potential irradiation, which could lead to an overestimation of internal contamination. Second, this study is limited to data from Minamisoma, and it is unclear whether these results are generalisable to other towns or villages. Third, in addition to food intake behaviours and the degree of soil contamination, additional factors such as the policies of each town or village, types of vegetables grown in each place, accessibility of radiation-related information and fear of radiation may differ greatly even within the Fukushima Prefecture. These results may not be applicable to residents living in areas that are more highly contaminated than those in this study.

Conclusion

Low levels of internal and soil contamination were not associated, and only loose associations were observed in areas with slightly higher levels of soil contamination in Fukushima, most likely due to the rigorous control of market food. Thus, individual WBC measurements are essential for the precise evaluation of chronic internal radiation contamination among residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Minamisoma city employees and all measurement staff at Minamisoma Municipal General and Watanabe Hospitals, especially Masatsugu Tanaki, Emi Maeda, Minoru Kobayashi and Tatsuo Hanai, for data collection and management. Without their involvement, our study could not have reached its present form.

Footnotes

Contributors: MT, KS, TM and YK acquired the data, which were analysed and interpreted by all the authors. MT, SN, SK and CL drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised for important intellectual content by all the authors. SN and TF performed the statistical analyses. TO and YK provided administrative, technical and material support. SK, TO and YK served as the study supervisors. All authors were responsible for the study concept and design. All authors have approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by Japan Health Foundation grant number 145100000258 (MT).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of University of Tokyo approved the study design (authorisation number 25-40-1011). For the use of internal contamination data, written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kamiya K, Ozasa K, Akiba S et al. Long-term effects of radiation exposure on health. Lancet 2015;386:469–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61167-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNSCEAR. Summary of low-dose radiation effects on health. UNSCEAR 2010 Report: “Summary of low-dose radiation effects on health” New York: United Nations, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimoto A, Nomura S, Tsubokura M et al. The relationship between media consumption and health-related anxieties after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e65331 10.1371/journal.pone.0065331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Likhtarev IA, Kovgan LN, Vavilov SE et al. Internal exposure from the ingestion of foods contaminated by 137Cs after the Chernobyl accident. Report 1. General model: ingestion doses and countermeasure effectiveness for the adults of Rovno Oblast of Ukraine. Health Phys 1996;70:297–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsubokura M, Kato S, Nomura S et al. Reduction of high levels of internal radio-contamination by dietary intervention in residents of areas affected by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster: a case series. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e100302 10.1371/journal.pone.0100302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toohey RE. Scientific issues in radiation dose reconstruction. Health Phys 2008;95:26–35. 10.1097/01.HP.0000285798.55584.6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pröhl G, Mück K, Likhtarev I et al. Reconstruction of the ingestion doses received by the population evacuated from the settlements in the 30-km zone around the Chernobyl reactor. Health Phys 2002;82:173–81. 10.1097/00004032-200202000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNSCEAR. Annex D: exposures from the Chernobyl accident. UNSCEAR 1988 report: sources, effects and risks of ionizing radiation New York: United Nations, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura Y, Okubo Y, Hayashida N et al. Evaluation of the relationship between current internal 137Cs exposure in residents and soil contamination west of Chernobyl in Northern Ukraine. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0139007 10.1371/journal.pone.0139007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nisbet AF, Woodman RF. Soil-to-plant transfer factors for radiocesium and radiostrontium in agricultural systems. Health Phys 2000;78:279–88. 10.1097/00004032-200003000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarkrog A. Environmental studies on radioecological sensitivity and variability with special emphasis on the fallout nuclides Sr-90 and Cs-137 Rise-R-437. Vol Part II. Roskilde, Denmark: Rise National Laboratory, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zvonova IA, Jesko TV, Balonov MI et al. 134Cs and 137Cs whole-body measurements and internal dosimetry of the population living in areas contaminated by radioactivity after the Chernobyl accident. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 1995;62:213–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rääf CL, Hubbard L, Falk R et al. Ecological half-time and effective dose from Chernobyl debris and from nuclear weapons fallout of 137Cs as measured in different Swedish populations. Health Phys 2006;90:446–58. 10.1097/01.HP.0000183141.71491.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ICRP. ICRP publication 67: age-dependent doses to members of the public from intake of radionuclides—part 2 ingestion dose coefficients. Vol 23 New York: International Commission on Radiological Protection, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNSCEAR. Annex C: radioactive contamination due to nuclear explosions. UNSCEAR 1977 report: sources and effects of ionizing radiation New York: United Nations, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinhauser G, Brandl A, Johnson TE. Comparison of the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear accidents: a review of the environmental impacts. Sci Total Environ 2014;470–471:800–17. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merz S, Shozugawa K, Steinhauser G. Analysis of Japanese radionuclide monitoring data of food before and after the Fukushima nuclear accident. Environ Sci Technol 2015;49:2875–85. 10.1021/es5057648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, Yan W, Oba A et al. Radiation-driven migration: the case of Minamisoma City, Fukushima, Japan, after the Fukushima nuclear accident. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:9286–305. 10.3390/ijerph110909286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayano RS, Watanabe YN, Nomura S et al. Whole-body counter survey results 4 months after the Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP accident in Minamisoma City, Fukushima. J Radiol Prot 2014;34:787–99. 10.1088/0952-4746/34/4/787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsubokura M, Kato S, Nomura S et al. Absence of internal radiation contamination by radioactive cesium among children affected by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster. Health Phys 2015;108:39–43. 10.1097/HP.0000000000000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Japan_Atomic_Energy_Agency. Airborne Monitoring in the Distribution Survey of Radioactive Substances. http://emdb.jaea.go.jp/emdb/en/portals/b224/ (accessed 9 Dec 2015).

- 22.Nomura S, Tsubokura M, Gilmour S et al. An evaluation of early countermeasures to reduce the risk of internal radiation exposure after the Fukushima nuclear incident in Japan. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:425–33. 10.1093/heapol/czv080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugimoto A, Gilmour S, Tsubokura M et al. Assessment of the risk of medium-term internal contamination in Minamisoma City, Fukushima, Japan, after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident. Environ Health Perspect 2014;122:587–93. 10.1289/ehp.1306848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarkrog A. Concept of seasonality in the light of the Chernobyl accident. Analyst 1992;117:497–9. 10.1039/an9921700497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rääf CL, Hubbard L, Falk R et al. Transfer of 137Cs from Chernobyl debris and nuclear weapons fallout to different Swedish population groups. Sci Total Environ 2006;367:324–40. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsubokura M, Kato S, Nihei M et al. Limited internal radiation exposure associated with resettlements to a radiation-contaminated homeland after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e81909 10.1371/journal.pone.0081909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim E, Kurihara O, Tani K et al. Intake ratio of 131I to 137Cs derived from thyroid and whole-body doses to Fukushima residents. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2016;168:408–18. 10.1093/rpd/ncv344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNSCEAR. Annex A: levels and effects of radiation exposure due to the nuclear accident after the 2011 great east-Japan earthquake and tsunami. UNSCEAR 2013 report: sources, effects and risks of ionizing radiation New York: United Nations, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamashita J, Enomoto T, Yamada M et al. Estimation of soil-to-plant transfer factors of radiocesium in 99 wild plant species grown in arable lands 1 year after the Fukushima 1 Nuclear Power Plant accident. J Plant Res 2014;127:11–22. 10.1007/s10265-013-0605-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujimura S, Muramatsu Y, Ohno T et al. Accumulation of (137)Cs by rice grown in four types of soil contaminated by the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident in 2011 and 2012. J Environ Radioact 2015;140:59–64. 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2014.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonze MA, Mourlon C, Calmon P et al. Modelling the dynamics of ambient dose rates induced by radiocaesium in the Fukushima terrestrial environment. J Environ Radioact 2016;161:22–34. 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa A, Tanigawa K, Ohtsuru A et al. Health effects of radiation and other health problems in the aftermath of nuclear accidents, with an emphasis on Fukushima. Lancet 2015;386:479–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohtsuru A, Tanigawa K, Kumagai A et al. Nuclear disasters and health: lessons learnt, challenges, and proposals. Lancet 2015;386:489–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60994-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]