Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomies (LCs) are the gold standard treatment of symptomatic gallstone disease worldwide. However, with this technique comes the increased risk of retained spilled gallstones. We describe a case of a 77-year-old man who presented 2 months after undergoing a LC, with right upper quadrant pain. Abdominal ultrasound scan showed no significant complications, but he continued to have grumbling pains. These were investigated with an abdominal CT scan, prompting suspicion of a colorectal malignancy with pleural metastasis. However, on review by two different multidisciplinary teams, the final conclusion was probable residual gallstones with associated inflammation. This diagnosis was rather dramatically confirmed when the patient went on to expel gallstones percutaneously from his back and coughed out of his respiratory tract. This case highlights the importance of operative documentation of spilled gallstones, which can, in addition to more surprising consequences, mimic malignancy on investigation. This can lead to delay in correct management and cause undue patient distress.

Background

Laparoscopic cholecystectomies (LCs) have become the gold standard for surgically treating symptomatic gallstones. It is estimated that gallstones are spilled in 6–30% of LCs, making this a relatively common complication.1 2 During an open procedure, spilled gallstones can be more easily retrieved using sponges and direct vision; however, this is more technically difficult with a laparoscopic approach. Complications from gallstones spilled during routine LC are said to occur in around 0.08–0.3% of cases and can lead to significant morbidity.3 4

The progression of spilled gallstones to complications has been attributed to the presence of infected bile and multiple pigmented stones that lead to an inflammatory reaction and abscess formation.5 Other complications include sinuses, pseudo-obstruction, haematuria and cholelythoptysis (coughing up gallstones) among others.6–9

A recent review of the literature by Sathesh-Kumar et al10 recommended that secondary prevention (ie, after spillage) should ideally consist of good irrigation with saline to dilute any infected bile, and all stones should be gathered into a retrieval bag or even a surgical glove, if possible.11

In our case, after the spillage of gallstones during a difficult LC for severe cholecystitis complicated by multiple adhesions, 3 L of saline was used to washout the patient's abdomen. Recovery of the spilled stones was subsequently attempted but not successful due to their microscopic nature.

The key learning point of this case was the striking similarity of the patient's symptoms to a clinical presentation of malignancy with metastasis. It identifies the clear need to make the patient and other clinicians acutely aware when gallstones are spilled during an LC so that this is considered as a differential during future hospital admissions and clinical encounters.

Case presentation

A 77-year-old man presented to his general practitioner (GP) 2 months after a LC for severe cholecystitis, reporting of pain in his right upper quadrant, which was sharp in nature and had ‘just not settled since his operation’, and was no longer manageable with regular analgaesia.

His medical history comprised of a coronary artery bypass grafting for ischaemic heart disease, previous transient ischemic attacks and depression.

He was seen in the Upper gastrointestinal outpatient clinic. An ultrasound scan was performed, which, although technically difficult due to his body habitus and overlying bowel gas, showed neither collection nor haematoma, and the biliary system looked of normal calibre.

One month later, he was referred again by his GP, this time to the care of the elderly physicians, with persistent lethargy, general malaise, persistently raised inflammatory markers and an episode of haemoptysis. On examination, he looked generally unwell, with some mild tenderness in his right loin and lower quadrant but no palpable masses. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. A CT scan of his abdomen was then arranged. There was a degree of suspicion at this point that the correlation between onset of symptoms and his recent operation might not be a coincidence.

Investigations

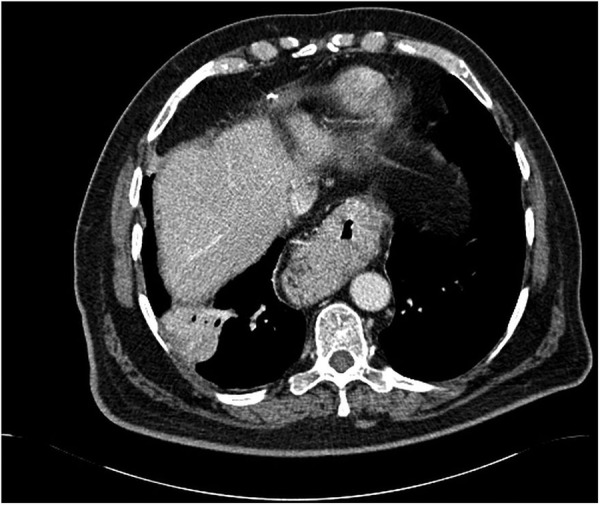

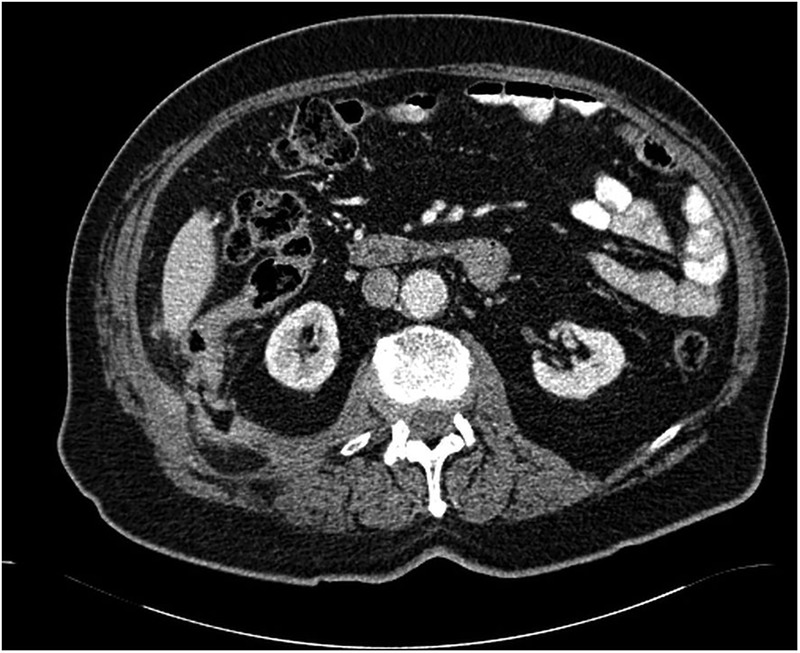

CT of the abdomen showed a new soft tissue mass (3 cm) abutting the pleura and the right lung base, with a significant thickening of the colon just proximal to the hepatic flexure (figures 1 and 2), with appearances in keeping with a contained retroperitoneal perforation.

Figure 1.

CT imaging of the base of the right lung showing a suspicious inflammatory lesion.

Figure 2.

CT imaging of the splenic flexure showing significant retroperitoneal inflammation with perforation of the bowel.

Differential diagnosis

Radiological diagnosis was as follows: perforated malignancy of ascending colon with peritoneal and right basal pleural deposits. Iatrogenic injury to ascending colon during this patient's LC seemed very unlikely given its retroperitoneal position, but there were some postoperative inflammatory changes surrounding the gallbladder bed.

Treatment

In view of the CT scan results, the patient was investigated with a colonoscopy and bronchoscopy to exclude possible malignancy. These results were discussed at the lung and colorectal multidisciplinary team meetings, where the presence of a malignancy was excluded, and it was concluded that the patient's symptoms were due to a chronic sepsis secondary to spilt gallstones. This had produced an inflammatory reaction in Morrison's pouch and in the right pleural base transdiaphragmatically.

Outcome and follow-up

Two weeks later the patient re-presented to his GP, with a 5×3 cm hard, tender and immobile lump in his right lumbar region. With the concern that this might be a possible metastatic deposit, the patient was admitted to hospital.

The patient was taken to theatre for an exploration under anaesthesia of his right lumbar region. This revealed a fistula expelling numerous stones.

It was concluded that the patient's spilled gallstones had led to inflammatory reactions in Morrison's pouch, affecting the retroperitoneal colonic wall at the hepatic flexure and, interestingly, in the posterior abdominal wall, with fistula formation through to the right lumbar region.

The spilled gallstones also produced an inflammatory mass in the right lower lobe of his lung, involving the bronchioles, possibly due to transdiaphragmatic inflammation and subsequent fistula formation through the diaphragm. This led to repeated episodes of small volume haemoptysis during admission, including the exporating of three gallstones! Both events were the consequence of normal chronic inflammatory processes designed to expel foreign bodies, in this case, gallstone fragments.

A repeat CT scan at 6 months showed resolution of both, the pleural and pericolonic inflammation, and on review in clinic, the patient's symptoms had resolved with a full return to normal life.

Discussion

The surgical literature is rife with case reports documenting the array of clinical presentations associated with complications from spilled gallstones, as reviewed by Sathesh-Kumar et al.10 Of note, these complications can occur days to years after the original operation, with case reports of intra-abdominal abscesses occurring over a year later.7 8

Spilled gallstones most commonly occur due to perforation of the gallbladder by laparoscopic instruments or during dissection of the gallbladder from the hepatic bed. An increased risk of perforation of the gallbladder has been shown in acutely inflamed gallbladders as well as those surrounded with dense adhesions.10 Therefore, in cases with higher risk of perforation, surgeons should be acutely aware of the need for precise dissection with careful handling of friable tissue and, if available, use retrieval bags for the storage and removal of the gallbladder from the abdomen.

If gallstones are spilled, the recommended secondary prevention consists of good irrigation with saline to dilute any infected bile, and all stones should be retrieved into a retrieval bag or even a surgical glove, if possible.12 The Sathesh-Kumar review also upheld the opinion that conversion to open surgery to retrieve spilled gallstones is not supported and would lead to overall increased patient morbidity. Another case report has supported inserting a drain and giving antibiotics to patients with retained stones, but this is not supported elsewhere in the literature.13

Of interest to this case, complications from spilled gallstones appear to commonly manifest in only one presentation for each patient. Both cholelithoptysis and lumbar/flank abscesses have been noted in individual previous cases, but not with a combined presentation, as with this unfortunate patient.7 9

In this case, the intraoperative management of spilled gallstones was in line with expert opinion and, on reflection, it seems that any further initial intervention would have been overzealous. However, this case report highlights the need to have a clear record in the operative note of any spilled gallstones and the action taken as prevention of spilled gallstones is evidently preferential to managing the consequences. As demonstrated here, complications can have far reaching impact from increased stress for the patient, workload for doctors and cost to the hospital.

Learning points.

Patients who have spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomies should be informed postprocedure and the information documented clearly in the operation note.

This information should be included in referrals/multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) when masses or abscesses are found postoperatively, with a high degree of suspicion that spilled gallstones may be the causative agent if symptoms are clearly linked to the operation date.

This case proves the clear benefit of an MDT discussion of difficult cases where a complete review of the patient’s notes can be achieved with many highly skilled specialists in attendance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Schäafer M, Suter C, Klaiber C et al. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A relevant problem? A retrospective analysis of 10,174 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc 1998;12:305–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memon MA, Deeik RK, Maffi TR et al. The outcome of unretrieved gallstones in the peritoneal cavity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A prospective analysis. Surg Endosc 1999;13:848–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deziel DJ, Millikan KW, Economou SG et al. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a national survey of 4292 hospitals and an analysis of 77,604 cases. Arm J Surg 1993;165:9–14. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80397-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zehetner J, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W. Lost gallstones in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: all possible complications. Am J Surg 2007;193:73–8. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson EJ, Nagy AG. Don't cry over spilled stones? Complications of gallstones spilled during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report and literature review. Can J Surg 1997;40:300–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Läuffer JM, Krähenbühl L, Baer HU et al. Clinical manifestations of lost gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1997;7:103–12. 10.1097/00019509-199704000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zilbershtein S, Kessler A, Greenbertg R et al. Multilocular flank abscess due to stone migration following laparoscopic cholecystectomy with spillage of gallstones. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2006;16:374–7. 10.1089/lap.2006.16.374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simopoulos C, Polychronidis A, Perente S et al. Intraperitoneal Abscess after an undetected spilled stone. Sure Endosc 2000;14:594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quail JF, Soballe PW, Gramins DL. Thoracic gallstones: a delayed complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014;15:69–71. 10.1089/sur.2012.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sathesh-Kumar T, Saklani AP, Vinayagam R et al. Spilled gall stones during laparascopic cholecystectomy: a review of the literature. Postgrad Med J 2004;80:77–9. 10.1136/pmj.2003.006023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice DC, Memon MA, Jamison RL et al. Long-term consequences of intra-operative spillage of bile and gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 1997;1:85–90; discussion 90-1. 10.1007/s11605-006-0014-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helme S, Samdani T, Sinha P. Complications of spilled gallstones following laparascopic cholecystectomy: a case report and literature overview. J Med Case Rep 2009;3:8926 10.4076/1752-1947-3-8626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hand AA, Self ML, Dunn E. Abdominal wall abscess formation two years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS 2006;10:105–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]