Highlights

-

•

PI and HPVG caused by ischaemia usually results in death if conservatively managed.

-

•

A 93 year old male survived this despite non-operative management.

-

•

Aggressive surgical intervention is not always in the patients’ best interest.

-

•

Further work is needed to identify patients who may survive conservative treatment.

Keywords: Pneumatosis intestinalis, Hepatic portal venous gas, Conservative, Survival, Non-operative, Ischaemia

Abstract

Introduction

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) are typically associated and are likely to represent a spectrum of the same disease. The causes of both entities range from benign to life-threatening conditions. Ischaemic causes are known to be fatal without emergency surgical intervention.

Presentation of case

In this case a 93 year old male experienced acute abdominal pain radiating to his back, with nausea and vomiting and a 2-week history of altered bowel habit. Examination revealed abdominal tenderness and distension. He had deranged white cell count (WCC) and renal function. Computed tomography (CT) revealed PI with associated HPVG. The cause was due to ischaemic pathology. The patient was managed conservatively with antibiotics and was discharged 7 days later with resolution of his abdominal pain and WCC.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of HPVG secondary to PI is poorly understood but usually indicates intestinal ischaemia, thought to carry a mortality of around 75%. HPVG in the older patient usually necessitates emergency surgery however this is not always in the patient’s best interest.

Conclusion

There are few reported cases of patient survival following conservative management of PI and HPVG secondary to ischaemic pathology. This case demonstrates the possibility of managing this condition without aggressive surgical intervention especially when surgery would likely result in mortality due to frailty and morbidity. Further work is required to identify suitable patients.

1. Introduction

The use of computed tomography (CT) has resulted in a more frequent diagnosis of pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) [1], [2]. PI is characterised by submucosal gas within the gastrointestinal tract. HPVG is defined as gas anywhere within the portal venous system from the superior mesenteric vein and its tributaries to the intrahepatic system. HPVG is typically allied with PI and is likely to represent a spectrum of the same disease [1], [3]. Both entities result from a variety of benign to life-threatening pathologies. PI or HPVG caused by ischaemic disease, with or without mesenteric thrombus, has almost unanimously been reported to have fatal outcomes without operative intervention [1], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Here we report a rare case of PI and HPVG caused by ischaemic pathology which was managed conservatively without mortality. This document has been reported in line with the CARE criteria [9].

2. Case report

A 93 year old man presented with acute abdominal pain which radiated to his back, associated with nausea and vomiting. He had complained of altered bowel habit for 2 weeks prior to admission. He had generalised abdominal tenderness and distension but no features of peritonism. He was apyrexial. His blood pressure, pulse and oxygen saturations were all within normal limits. He had a background of type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, diverticulosis, varicose eczema, deep vein thrombosis for which he was taking warfarin and an extensive smoking history. He had no previous history of abdominal surgery. His WCC (white cell count) was elevated (18.1 × 109/L) and his renal function demonstrated acute kidney injury. His liver function and amylase remained normal. His INR was 3.4 and PTT 34.8 s. His arterial blood gas did not demonstrate acidosis and his lactate and bicarbonate were within normal range. An abdominal x-ray demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel.

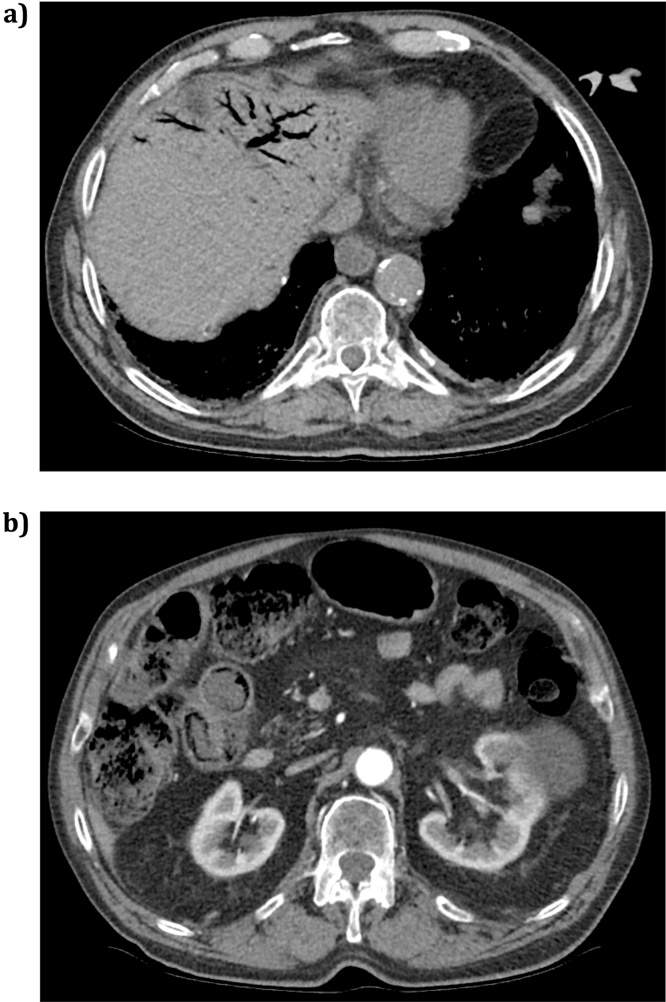

To exclude a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, a triple phase CT of his abdomen and pelvis was performed (Fig. 1). This was approximately 2 hours after admission to the emergency department. The CT demonstrated pneumatosis intestinalis in the terminal and distal ileum. The loops demonstrated wall oedema with increased enhancement on the arterial phase with marked surrounding vessel hyperaemia and fat stranding, strongly suggestive of acute small bowel ischaemia. There was also portal venous gas in the left lobe of the liver. The proximal and mid small bowel appeared normal. The coeliac axis, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) were all patent, but had non-stenotic calcification at their ostia. There was no evidence of mesenteric venous gas or intraperitoneal fluid or free air. The colon was faecally loaded and therefore ischaemic changes within the caecum could not be commented upon. The rest of the intra-abdominal organs appeared normal except for a large left renal cyst.

Fig. 1.

CT images from patient demonstrating (a) hepatic portal venous gas and (b) pneumatosis intestinalis in the terminal ileum.

Due to his co-morbidities and general frailty it was felt that he was unlikely to survive operative intervention. Therefore intravenous antibiotics were initiated for conservative management (piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g TDS) along with a nasogastric tube and intravenous fluids. His warfarin was withheld due to bleeding risk, though he was not given a reversal agent. His clinical condition improved following 5 days of IV antibiotics. His warfarin was restarted and he was subsequently discharged from hospital 7 days after admission, without abdominal pain, and his WCC had returned to normal range. The patient remained alive at the time of writing this article 3 months after the initial presentation.

3. Discussion

Due to the more liberal use of CT scanning in modern surgical units, PI and HPVG are increasingly detected [1], [2]. Most cases of HPVG are associated with PI and therefore PI and HPVG are likely to represent a spectrum of the same disease, with gas tracking through the portal venous system [1], [3].

PI causing HPVG has a poorly understood pathogenesis. Causes can broadly be separated into four categories: infection; mechanical; ischaemic; and iatrogenic. The pathogenesis of the mechanical theory can be explained by high pressures causing gas to track into the mesenteric veins from the intestinal lumen via intestinal endothelial and mucosal breakdown, such as in small bowel obstruction; or due to mucosal breaches in ulcerative disease [3], [4]. The bacterial theory is thought to result from fermenting bacteria passing into the submucosa, resulting in PI which tracks into the HPV [3], [4]. Ischaemic pathology results in breaches of the mucosal surface and proliferation of gas producing organisms [2]. In ischaemic disease, arterial embolic disease is the most common cause; however low-flow secondary to sepsis, venous thrombosis, vasculitis and arterio-spasm have also been documented [1], [8], [10]. Iatrogenic causes of portal venous gas include GI luminal instrumentation, vascular cannulation, or pharmacotherapy [2], [3].

HPVG associated with PI usually indicates intestinal ischaemia or necrosis and was previously thought to carry an “all-cause” mortality of around 75% [3], [5], [8], [11], [12], [13]. However, more recent studies have demonstrated a mortality of less than 40%, though this includes benign and iatrogenic causes of HPVG [11], [14], [15]. This improvement in mortality may also be at least partially explained by the increased use of CT, or by improved emergency surgical technique and decision making [10]. HPVG in the older patient is even more suggestive of mesenteric ischaemia and is usually a peri-mortem sign, indicating a necessity for emergency surgery [3]. Although early surgical intervention in ischaemic pathology can be lifesaving, it still carries high mortality [1], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [10], [16]. In extremes of age, and when a patient has extensive co-morbidities, surgery may not be in the patient’s best interest, as the laparotomy may also not be survivable [1]. However, here we have reported a case of mesenteric ischaemia, resulting from impaired arterial flow secondary to sepsis, causing PI and HPVG. The patient was treated conservatively with non-operative management and survived to be discharged from hospital.

It would be beneficial to distinguish accurately between those cases of PI and HPVG that require operative intervention, as an emergency, and those where conservative treatment may be indicated; especially if they are unlikely to survive an operation. Wayne et al. reviewed 88 cases of HPVG or PI, in 86 patients [1]. In their ischaemic series, all patients had extensive cardiovascular risk factors, and lactate levels were normal in approximately 50% of these patients, as with our patient. The authors concluded that lactate, pH, WCC and bicarbonate were poor predictors of ischaemia [1]. Again, like the present patient, there were a large number of patients in their ischaemic subgroup who had both large and small bowel PI, suggesting SMA involvement. All four patients who were managed non-operatively, died during this author’s series [1]. However, our patient has identified that there are a small number of patients who may survive ischaemic pathology without operative intervention using antibiotic therapy. Urokinase and prostaglandin E1 have been suggested as suitable additions to the emergency surgeon’s armoury when dealing with PI and HPVG in ischaemic pathology but they were not used in this case [8], [12]. We therefore believe that in some cases of ischaemic HPVG and PI, the decision not to operate should not be considered to carry a 100% mortality rate, especially where the surgeon has doubts regarding “fitness for theatre.”

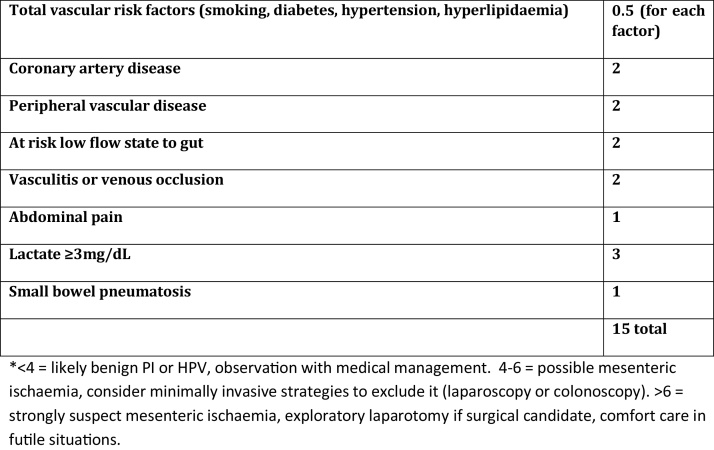

It could be argued that this case was not caused by ischemic pathology however Wayne et al. also reviewed patients with PI and HPVG due to benign pathology, few had cardiovascular risk factors, and they had an average age of 57, much lower than the ischaemic group [1]. 10 patients in this group who were managed non-operatively were alive at 30 days [1]. Only 8% of patients with benign disease had a vascular disease score > 4 (Fig. 2), both had negative laparotomies, and were discharged without complications. According to their algorithm our patient would have scored 9.5; therefore it is highly likely that his PI and HPVG was indeed caused by mesenteric ischaemia. Despite this, he survived with conservative management.

Fig. 2.

Proposed vascular disease score adapted from publication by Wayne et al. [1]. Assuming the patient is not critically ill and does not have a mechanical or iatrogenic cause of PI or HPVG the patient should be assessed using this score.

McElvanna et al. also demonstrated two cases of HPVG due to non-ischaemic pathology; both of which survived non-operative management [11]. It is therefore necessary to identify patients with benign versus ischaemic pathology, due to the poor non-operative outcome in the ischaemic group. Wayne et al. concluded that coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, abdominal pain, lactate greater than 3 mg/dL and small bowel PI were all predictors of ischaemic pathology (Fig. 2) [1]. The present patient had all of these except a raised lactate. Greenstein et al. also attempted to determine the need for surgical intervention in PI. The authors concluded that a WCC > 12 × 109/L, age greater than or equal to 60 years, emesis and HPVG were indicators for the need for surgical intervention [4]. Once more, our patient had all 4 of these, and was treated conservatively with good result.

There have been a small number of previously reported survivors of ischaemic PI and HPVG who underwent conservative treatment, Pineda Bonilla et al. reported a 68 year old with HPVG secondary to gastric ischaemia resulting from a peptic ulcer which resolved with conservative care, however the authors did not specify their management strategy [17]. Ohtsubo et al. reported a case of PI and HPVG in an 82 year old who survived with conservative treatment consisting of urokinase and total parenteral nutrition [12]. Our report has detailed specific management strategies that the authors used to care for this patient. Further evaluation is needed to identify which patients may survive conservative therapy.

4. Conclusion

To our knowledge there have only been a small number of case reports of survivors of non-operative management of PI and HPVG secondary to ischaemic pathology [12], [17], [18]. Our report suggests that in select cases it is possible to manage PI and HPVG without aggressive surgical intervention, especially if the patient was unlikely to survive surgery. Surgeons should be reminded that the decision to manage a patient conservatively does not result in certain mortality. Further work must be done to identify patients who can be managed successfully in this way, especially when operative management is high risk.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical approval

There was no ethical approval required for this case report.

Funding

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this information.

Author contribution

EJN, CSJW, KM, CEE and JVT were responsible for the patients’ care. EJN and PM wrote the original manuscript. CSJW, KM, CEE and JVT critically reviewed and made multiple revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved the report prior to submission.

Guarantor

Edward J Nevins.

References

- 1.Wayne E., Ough M., Wu A. Management algorithm for pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas: treatment and outcome of 88 consecutive cases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010;14(3):437–448. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abboud B., El Hachem J., Yazbeck T., Doumit C. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15(29):3585–3590. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammed H., Khot U.P., Thomas D. Portal venous gas–case report and review of the literature. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(4):400–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenstein A.J., Nguyen S.Q., Berlin A. Pneumatosis intestinalis in adults: management, surgical indications, and risk factors for mortality. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2007;11(10):1268–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan S.C., Wan Y.L., Cheung Y.C., Ng S.H., Wong A.M.C., Ng K.K. Computed tomography findings in fatal cases of enormous hepatic portal venous gas. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;11(19):2953–2955. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i19.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris M.S., Gee A.C., Cho S.D. Management and outcome of pneumatosis intestinalis. Am. J. Surg. 2008;195(5):679–683. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monneuse O., Pilleul F., Barth X. Portal venous gas detected on computed tomography in emergency situations: surgery is still necessary. World J. Surg. 2007;31(5):1065–1071. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsuyoshi A., Hamada S., Tachibana T. Pathogenic mechanisms of intestinal pneumatosis and portal venous gas: should patients with these conditions be operated immediately? Surg. Case Rep. 2015;1(104):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40792-015-0104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagnier J.J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013(5):38–43. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alqahtani S., Coffin C.S., Burak K., Chen F., MacGregor J., Beck P. Hepatic portal venous gas: a report of two cases and a review of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and approach to management. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2007;21(5):309–313. doi: 10.1155/2007/934908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McElvanna K., Campbell A., Diamond T. Hepatic portal venous gas-three non-fatal cases and review of the literature. Ulst. Med. J. 2012;81(2):74–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtsubo K., Okai T., Yamaguchi Y. Pneumatosis intestinalis and hepatic portal venous gas caused by mesenteric ischaemia in an aged person. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;36:338–340. doi: 10.1007/s005350170100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiesner W., Mortele K.J., Glickman J.N., Ji H., Ros P.R. Pneumatosis intestinalis and portomesenteric venous gas in intestinal ischemia: correlation of CT findings with severity of ischemia and clinical outcome. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001;177(6):1319–1323. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iannitti D.A., Gregg S.C., Mayo-Smith W.W., Tomolonis R.J., Cioffi W.G., Pricolo V.E. Portal venous gas detected by computed tomography: is surgery imperative? Dig. Surg. 2003;20(4):306–315. doi: 10.1159/000071756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita H., Shinozaki M., Tanimura H. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch. Surg. 2001;136(12):1410–1414. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson A.L., Millington T.M., Sahani D. Hepatic portal venous gas: the ABCs of management. Arch. Surg. 2009;144(6):575–581. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.88. (discussion 581) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pineda Bonilla J.J., Diehl D.L., Babameto G.P., Smith R.E. Massive hepatic portal venous gas and gastric pneumatosis secondary to gastric ischemia. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013;78:540. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muroya H.D., Hidaka A., Kojima S. A case of hepatic portal venous gas and pneumatosis intestinalis caused by transit type ischemia. J. Kurume Med. Assoc. 2014;77:325–330. [Google Scholar]