Abstract

Gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina is an autosomal recessive condition characterized by peripheral multiple sharp areas of chorioretinal atrophy which become confluent with age. Macula and central vision is typically involved late in the disease. Macular involvements such as cystoid macular edema, epimacular membrane, and choroidal neovascularization have been reported in gyrate atrophy. In this report, we present a family with diminished central vision presenting within 8 years of age. All of three siblings had typical peripheral chorioretinal atrophic lesions of gyrate atrophy and hyperornithinemia. On spectral domain optical coherence tomography, two of elder siblings showed macular edema. Hyporeflective spaces appeared to extend from outer nuclear layer to the inner nuclear layer level separated by multiple linear bridging elements in both eyes. Ultrawide field fluorescein angiogram (UWFI) even in late phase did not show any leak at macula suggesting foveoschisis. Foveoschisis in gyrate atrophy has not been reported before.

Keywords: Cystoid macular edema, fundus dystrophies, macular dystrophy, maculoschisis, scanning laser ophthalmoscope

Introduction

Ultrawide field imaging and fluorescein angiogram (UWFI, UWFA, Optos, Inc., Marlborough, Ma, USA) uses scanning laser technology to provide a pseudocolor image of the fundus up to 82% or 200 degrees compared to the available fundus cameras, which have field capturing capacity of 30° and 50° with maximum of 140° with montage. Gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina is a rare autosomal recessive chorioretinal dystrophy characterized by sharply demarcated circular or oval areas of chorioretinal atrophy in the mid periphery of fundus, which coalesce with time and spread anteriorly and posteriorly. Cystoid macular edema is a known complication of gyrate atrophy,[1,2,3] but no previous reports of foveoschisis exist in indexed peer-reviewed literature (PubMed search).

Case Reports

Three siblings - a 6-year-old male, a 7-year-old female, and an 8-year-old male presented to us with complaints of decreased vision. Parents were normal, with 6/6 vision in both eyes, and normal fundus. There was no history of consanguineous marriage.

Case 1

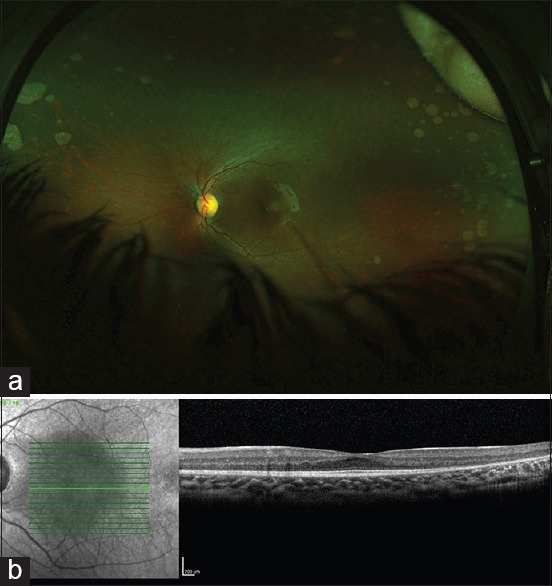

The youngest sibling, a 6-year-old boy, had best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/12 in both eyes. His anterior segment and intraocular pressures (IOP) were normal. There was no squint or nystagmus. Fundus showed few peripheral scalloped areas of chorioretinal atrophy in both eyes [Figure 1a]. Central macular thickness (CMT) in optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Spectralis® HRA + OCT, Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) was 271 μm in the right eye and 259 μm in the left eye, with no evidence of cysts or schisis in fovea [Figure 1b].

Figure 1.

(a) Ultrawide field fundus image of the left eye of youngest child of 6-year-old age (Case 1) shows peripheral scalloped lesions of gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina. (b) Optical coherence tomogram did not show any cystic changes at fovea

Case 2

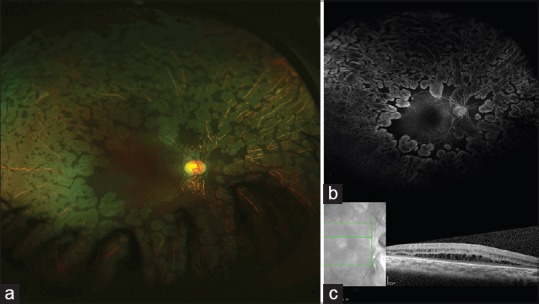

The 7-year-old girl had BCVA of 6/36 vision in the right eye and 6/24 in the left eye. There was no nystagmus or squint. Anterior segment examination and IOP were normal. There were sharply demarcated areas of focal chorioretinal atrophy in both fundi [Figure 2a]. Fluorescein angiogram even in the late phase did not show any leak at macula [Figure 2b]. There was increased CMT in both the eyes (CMT of 558 μm and 431 μm in the right and left eyes, respectively), with hyporeflective spaces separated by multiple linear bridging elements suggestive of foveoschisis [Figure 2c]. The schisis cavities coalesced at the foveal centre forming rounded cyst like cavities.

Figure 2.

(a) Ultrawide field fundus image of 7-year-old girl (Case 2) shows multiple distinct focal areas of chorioretinal atrophy suggestive of gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina. (b) Ultrawide field fundus fluorescein angiogram did not show any leak at macula even in late phase. (c) Optical coherence tomogram showed hyporeflective spaces separated by multiple linear bridging elements suggestive of foveoschisis

Case 3

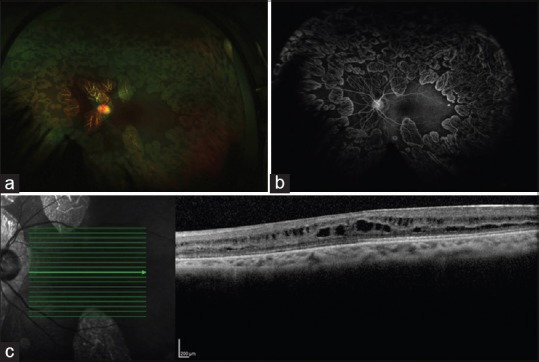

The oldest sibling, an 8-year-old boy, had BCVA of 6/36 vision in the right eye and 6/24 in the left eye. There was no nystagmus or squint. Anterior segment examination and IOP were normal. Multiple, coalescent areas of chorioretinal atrophy sparing the posterior pole were seen in both eyes. These were scalloped in appearance with well-circumscribed borders separating these from normal tissue [Figure 3a]. There was no leak at macula in the late phase of fluorescein angiogram [Figure 3b]. CMT was 308 μm in the right eye and 333 μm in the left eye, with multiple hyporeflective areas apparently extending from the outer nuclear layer to the inner nuclear layer with multiple vertical intervening bridges of retinal tissue suggestive of foveoschisis [Figure 3c]. Electroretinogram showed diminished rod response. Plasma ornithine level was 776.7 nmol/ml (normal 10-163 nmol/ml).

Figure 3.

(a) Ultrawide field fundus image of the left eye of 8-year-old boy (Case 3) shows multiple sharply demarcated lesions sparing macula, typical of gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina. (b) Ultrawide field fundus fluorescein angiogram did not show any leak at macula even in late phase. (c) Optical coherence tomogram showed multiple hyporeflective areas with vertical intervening bridges of retinal tissue suggestive of foveoschisis

Discussion

UWFI and UWFA help to evaluate fundus with a single panoramic view in choroidal dystrophies.[4] Early peripheral lesions of gyrate atrophy can be picked up with UWFI [Figure 1a]. Macula and central vision have been classically reported to be involved late in gyrate atrophy. Macular changes including cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membrane,[1] and choroidal neovascular membrane[5] have been reported in gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina. Oliveira et al.[2] reported one 12-year-old boy with hyperornithinemia, gyrate atrophy, and cystoid macular edema with leak at fovea on fluorescein angiogram. Time domain OCT showed “bilateral intraretinal cysts, areas of low reflectivity with occasional high-signal elements bridging the retinal layers and intraretinal thickening” in the patient. However, OCT findings and macular thickening in the absence of any leak at macula in UWFA even in late phase in our patients, suggest foveoschisis rather than cystoid macular edema. In the case series reported by Vannas-Sulonen,[3] the macula was affected in 9 of 21 patients. In six patients, there were pigment epithelial window defects at macula, in two patients, the patches of chorioretinal atrophy were central, and one patient had bilateral cystoid macular edema. Foveoschisis was seen in the two older siblings in this family (7 and 8 years of age), whereas the youngest sibling of 6-year-old age did not show foveoschisis. Thus, gyrate atrophy may present in pediatric age group with macular involvement and decrease in central vision in the form of foveoschisis. Early diagnosis is of prime importance to prevent progression of disease, especially in younger children because some cases may respond to oral pyridoxine therapy and arginine-restricted diet. UWFI and UWFA can help in documentation and monitoring of the peripheral lesions of gyrate atrophy in a single panoramic image.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge invaluable support and suggestions by Trina Sengupta Tripathy, without which the manuscript would have been incomplete. The authors acknowledge Prabhakar Singh, Rashmi Singh, Alkananda Behera, Abdul Rasheed, and Shreyans Jain for their help in data collection for the manuscript.

References

- 1.Feldman RB, Mayo SS, Robertson DM, Jones JD, Rostvold JA. Epiretinal membranes and cystoid macular edema in gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina. Retina. 1989;9:139–42. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198909020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira TL, Andrade RE, Muccioli C, Sallum J, Belfort R., Jr Cystoid macular edema in gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina: A fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography evaluation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:147–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vannas-Sulonen K. Progression of gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina. A long-term follow-up by fluorescein angiography. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1987;65:101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1987.tb08499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan A, Kaines A, Jain A, Reddy S, Schwartz SD, Sarraf D. Ultra-wide-field and autofluorescence imaging of choroidal dystrophies. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41:e1–5. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20101025-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marano F, Deutman AF, Pinckers AJ, Aandekerk AL. Gyrate atrophy and choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1295. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140495035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]