Abstract

Aim:

To evaluate and compare the efficacy of combination of ranibizumab or bevacizumab with photodynamic therapy (PDT) in treating choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) on long-term follow-up.

Materials and Methods:

Of 42 eyes, 18 were treated with bevacizumab (Group A) and 24 with ranibizumab (Group B) in combination with verteporfin PDT. Treatment was initiated after informed consent. Complete ophthalmic examination including optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed at presentation, 1 month, 3 months, and subsequent follow-up visits. OCT measures used were lesion thickness (LT) of the CNV, retinal thickness above the lesion (RT), and central macular thickness (CMT). Mean follow-up period was 33 months (median 18, range 1-84). Additional treatment on follow-up was left at treating surgeon's discretion.

Results:

Visual acuity improved significantly from baseline by 0.3 LogMAR in Group A and 0.26 LogMAR in Group B. LT decreased significantly from 1st month onward and remained significant at all the subsequent visits, in both the groups. CMT and RT showed a decreasing trend in both the groups. No difference was seen in visual acuity (VA), LT, CMT, and RT between Group A and Group B at any of the visits. The mean number of additional anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections given postcombination therapy were 1.5 (median 1, range 0-7) injections per eye.

Conclusions:

PDT in combination with either ranibizumab or bevacizumab was equally effective in preventing vision loss in eyes with wet-Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). Such combination also reduces the economic burden of the treatment.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, bevacizumab, choroidal neovascularization, combination therapy, photodynamic therapy, ranibizumab

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) has presented itself as a significant epidemiological public health challenge in both the developed and developing nations. According to the Western population-based studies such as Beaver Dam Eye Study and Blue Mountain Eye Study, the prevalence of ARMD varies from 1.7% to 1.2%.[1] ARMD is a major public health problem in India with a prevalence of early ARMD at 2.7% and late ARMD at 0.6% in a study in South Indian population.[2] A study conducted in India in 2007 revealed that the economic burden of treatment with ranibizumab for 2 years (26 weekly injections) amounts to $23,474.21 while bevacizumab on the other hand costs $722.28 though it is used as “off-label.”[3]

Along with the economic benefit of combination therapies, the rationale for combining the various therapies stems from the fact that a single therapy may not be able to counter all the pathophysiologic pathways acting via the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that lead to choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) formation and increased vascular permeability, the two main causes of reduced vision in ARMD. Anti-VEGF injections alone have thought to suppress the VEGF in short-term only to have a rebound as their effects wear off in 4-6 weeks. Similarly, the photodynamic therapy (PDT) induced collateral damage to capillaries adjacent to CNVM leading to capillary thrombosis, and subsequent ischemia of the normal retina may lead to an early rebound in VEGF production.[4] However, there is a theoretical possibility of achieving synergistic effects when both PDT and anti-VEGF are used in combination.

This paper is thus an attempt to investigate and compare the role of combination of PDT with the two commonly used anti-VEGF agents, bevacizumab and ranibizumab, in the management of ARMD in Indian population to reduce the economic burden.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective, interventional case series of patients diagnosed with wet-ARMD and treated with a combination of PDT with either ranibizumab or bevacizumab at a tertiary eye care hospital in India. The patients were divided into two groups, Group A consisting of patients treated with verteporfin-PDT and bevacizumab and Group B patients treated with verteporfin-PDT and ranibizumab. Patients with myopia >6 diopter, CNVM due to other causes, and the need for more than one PDT session were excluded from the study. Patients were followed up on the 1st postinjection day and then monthly for a minimum of 3 months. Each time visual acuity, slit lamp biomicroscopy, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed while fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was done when indicated.

Assessments

A detailed history and a complete ophthalmic examination followed by FFA and OCT were performed.

Optical coherence tomography parameters

OCT (Stratus Zeiss, GmBH USA) was used to measure (1) lesion thickness (LT) defined as the actual height of the lesion, (2) retinal thickness (RT) above the lesion (measured from anterior border of the retinal nerve fiber layer to the anterior border of the lesion), and (3) central macular thickness (CMT) measured by 6 mm macular thickness scan passing through the central 1 mm of the macula manually by means of calipers.

Technique of photodynamic therapy and intravitreal injections

PDT preceded the anti-VEGF injection by 2 days, and all other measures were taken to minimize light exposure. Full fluence PDT was performed using verteporfin dye as per the TAP protocol while 0.05 ml bevacizumab or ranibizumab was injected at the discretion of the treating physician with standard aseptic technique in operation theater after written informed consent and disclosure of off-label status of bevacizumab.

Criteria for retreatment

The retreatment was based on evidence of activity in CNVM including subretinal fluid (SRF), new exudates, increased RT on OCT and active leakage on FFA.

Anatomical outcome

On examination: Any signs of activity of the CNVM (exudation, SRF)

On OCT: Reduction in lesion size, absorption of SRF, reduction in retinal edema overlying the CNVM, and backscattering.

Functional outcome

An improvement was defined by gain in visual acuity by 2 Snellen lines and a fall by 2 lines was considered as deterioration. One Snellen line plus or minus the presenting visual acuity was defined as stable.

All the best-corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) were converted to LogMAR using standard conversion chart of Holladay et al.

Statistical analysis

Grouped statistics was analyzed using parametric paired t-test and nonparametric (Mann-Whitney test) wherever appropriate. Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS software version 9.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was assumed when P < 0.05.

All the study methods adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki 1968 guidelines.

Ethical committee clearance was obtained for the project.

Results

Patient characteristics

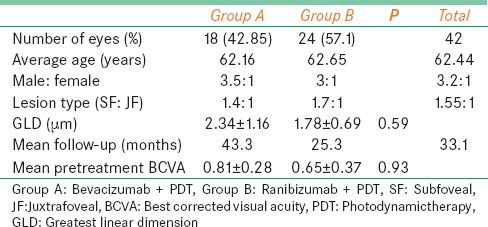

Of 148 patients treated for ARMD between January 2006 and June 2007, 42 were divided into two groups. Group A, comprising 18 patients, were treated with intravitreal bevacizumab and PDT and Group B, comprising 24 patients, treated with intravitreal ranibizumab and PDT. The mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of all patients was 62.4 ± 9.4 years (Group A was 62.16 years, Group B was 62.65 years). The male to female ratio was 3.5:1 in Group A and 3:1 in Group B. Systemic diseases such as hypertension was seen in 15 (36%) patients and diabetes mellitus was seen in 8 (19%) patients. The mean ± SD LogMAR BCVA was 0.81 ± 0.28 LogMAR in Group A and 0.65 ± 0.37 in Group B. The mean follow-up period in Group A was 43 months (median: 47; range: 3-84) while in Group B, it was 25 months (median: 17; range: 3-74) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Combination photodynamic therapy with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: Baseline characteristics

Treatment outcome in Group A

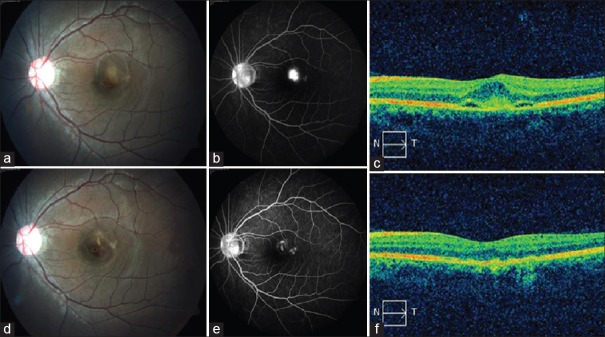

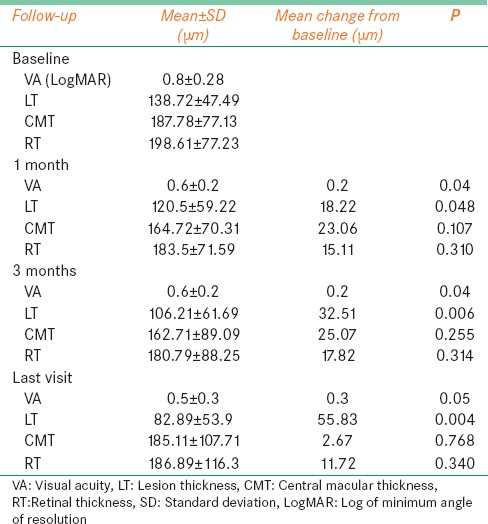

Baseline VA, LT, CMT, and RT over the lesion in Group A were 0.8 ± 0.28 LogMAR, 138.72 ± 47.49 μm, 187.78 ± 77.13 μm, and 198.61 ± 77.23 μm, respectively. Significant improvements in visual acuity were seen at 1 month (P = 0.04), 3 months (P = 0.04), and last follow-up (P = 0.05). Similarly, LT decreased significantly postcombination therapy to 120 ± 59.22 μm at 1 month (P = 0.048), 106.21 ± 61.69 μm at 3 months (P = 0.006), and 82.89 ± 53.9 μm at last follow-up (P = 0.004). Although both CMT and RT showed a decreasing trend, they could not reach statistical significance at any follow-up [Table 2]. Figure 1 demonstrates the resolution of CNV following PDT with bevacizumab after 3 months.

Table 2.

Combination photodynamic therapy with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: Treatment outcome in Group A

Figure 1.

(a) Fundus photograph shows juxtafoveal choroidal neovascular membrane with associated hemorrhage and subretinal fluid. (b) Fundus fluorescein angiography late phase shows intense leak from choroidal neovascularization with fuzzy borders. (c) Optical coherence tomography shows spindle-shaped hyper-reflective membrane between retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina with subretinal fluid. (d) Fundus image 3 months postphotodynamic therapy and bevacizumab shows regression of choroidal neovascularization, resolution of retinal hemorrhage, and subretinal fluid. (e) Late phase fundus fluorescein angiography shows minimal staining of the scar with no leakage. (f) Optical coherence tomography demonstrates complete resolution of the subretinal fluid with normal foveal dip and regression of the membrane

Treatment outcome in Group B

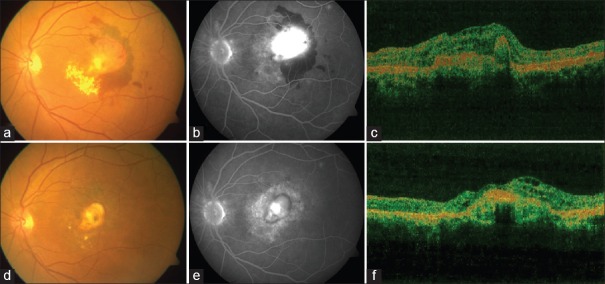

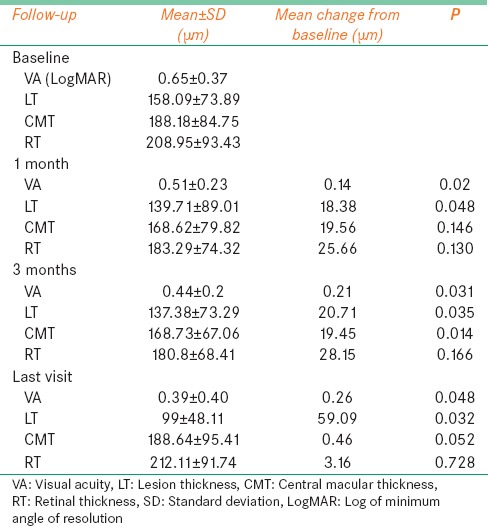

Baseline VA, LT, CMT, and RT over the lesion in Group B were 0.65 ± 0.37 LogMAR, 158.09 ± 73.89 μm, 188.18 ± 84.75 μm, and 208.95 ± 93.43 μm, respectively. VA showed significant improvement postcombination therapy. It improved to 0.51 ± 0.23 LogMAR at 1 month (P = 0.02), 0.44 ± 0.2 LogMAR at 3 months (P = 0.031), and 0.39 ± 0.40 LogMAR (P = 0.048) at last visit. LT also decreased significantly to 139.71 ± 89.01 μm at 1 month (P = 0.048), 137.38 ± 73.29 μm at 3 months (P = 0.035), and 99 ± 48.11 μm at last visit (P = 0.032). CMT decreased to 168.62 ± 79.82 μm at 1 month (P = 0.146), 168.73 ± 67.06 μm at 3 months (P = 0.014), and 188.64 ± 95.41 μm at last visit (P = 0.052). RT over the lesion was 183.29 ± 74.32 μm at 1 month (P = 0.13), 180.8 ± 68.41 μm at 3 months (P = 0.166), and 212.11 ± 91.74 μm at last visit (P = 0.728) [Table 3]. Figure 2 demonstrates the resolution of CNV following PDT with ranibizumab after 3 months.

Table 3.

Combination photodynamic therapy with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: Treatment outcome in Group B

Figure 2.

(a) Fundus image shows large subfoveal choroidal neovascularization with fresh subretinal hemorrhage and exudates. (b) Late phase fundus fluorescein angiography shows intense leakage from choroidal neovascularization and shadowing from subretinal hemorrhage. (c) Optical coherence tomography reveals hyperreflective membrane between retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina with subretinal fluid and overlying retinal thickening. (d) Fundus image 3 months after combination therapy with ranibizumab shows regression of choroidal neovascularization and resolution of subretinal hemorrhage. (e) Staining of the scar seen on late stage of fundus fluorescein angiography. (f) Optical coherence tomography reveals shadowing from scarred membrane with resolution of surrounding edema

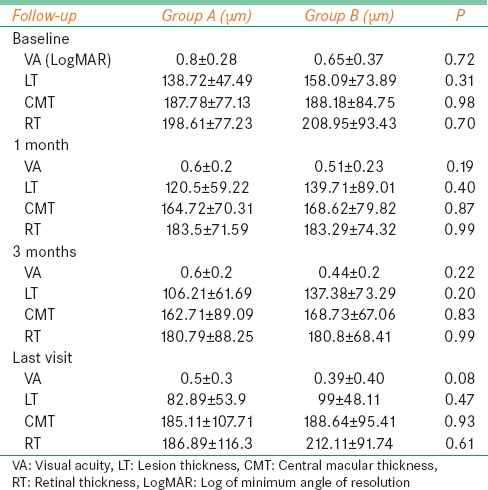

Comparison between the groups

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar in both the groups [Tables 1 and 4]. There was no statistically significant difference in any of the functional and anatomical parameters evaluated in the study between the two groups at any follow-up. Both the groups were equally effective in the management of choroidal neovascularization secondary to ARMD [Table 4].

Table 4.

Combination photodynamic therapy with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: Comparison of visual acuity, lesion thickness, central macular thickness, and retinal thickness between the groups

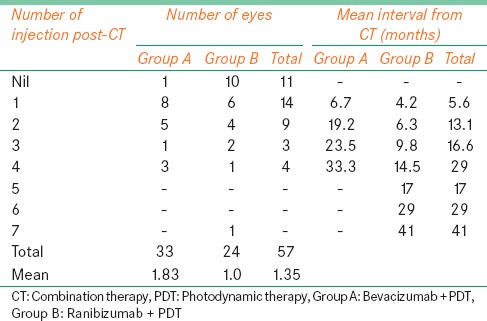

Additional treatment on long-term follow-up

The mean follow-up period of all the patients was 33 months. Overall, 57 anti-VEGF injections were given postcombination therapy, out of which 33 (58%) injections were given to Group A and 24 (42%) were given to group B. The mean number of additional injections given in Group A was 1.83 (1, 0-4) injections per eye while it was 1.0 (1, 0-7) injection per eye in Group B. Eleven eyes (26%) did not receive any additional treatment postcombination therapy. Fourteen eyes received 1 injection, 9 eyes received 2 injections, 3 eyes received 3 injections, and 4 eyes received 4 anti-VEGF injections postcombination therapy. Only 1 patient from Group B received a total of 7 additional anti-VEGF injections postcombination therapy [Table 5].

Table 5.

Combination photodynamic therapy with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration: Additional treatment on follow-up

The average interval between the first and additional injections given postcombination therapy was 6.7 months in Group A while it was 4.2 months in Group B. For those who received 2nd injection, the average interval from combination therapy was 19.2 months in Group A and 6.3 months in Group B while it was 23.5 months in Group A and 9.8 months in Group B for 3rd injection. The average interval for 4th injection was 33.3 months in Group A and 14.5 months in Group B. Only one patient received more than 4 injections postcombination therapy [Table 5].

Discussion

This study shows that both bevacizumab and ranibizumab are equally effective when combined with PDT for the management of wet-ARMD. Furthermore, combination therapy drastically reduces the total number of anti-VEGF injections required for the treatment, hence reduces the economic burden of the disease.

While ranibizumab is an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of CNVM in ARMD, bevacizumab is used as an “off-label” drug.[3] The safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in management of wet-ARMD have been well-established by MARINA[5] and ANCHOR[6] trials. The noninferiority of bevacizumab when compared to ranibizumab has also been well established by CATT[7] and IVAN[8] trials. Both of these drugs can theoretically be combined with PDT.

The TAP[9] study demonstrated the benefits of PDT in predominantly classic subfoveal choroidal neovascularization. In the VIO[10] study, which evaluated the role of PDT in occult with no classic CNV, no significant difference in VA was noted in the PDT and the sham groups. Such limited benefits of PDT in occult and minimally classic CNV could possibly be related to the deeper location of these membranes reducing the amount of light exposure during treatment. Anti-VEFGs are believed to be more effective in such deeply located membranes as they can attain significant concentration within the lesion by diffusion.[11] PDT has been shown to be inferior to ranibizumab when both used as monotherapy.[6]

The DENALI[4] study group evaluated the role of combination therapy of PDT with ranibizumab in the management of predominantly classic neovascularization secondary to ARMD and demonstrated the noninferiority of the combination therapy when compared with ranibizumab monotherapy. MONT BLANC[12] study also showed comparable results between the combination group and ranibizumab monotherapy group. Lazic and Gabric[11] reported beneficial effect of combination of bevacizumab with PDT.

The findings of our study demonstrate that both the combinations of ranibizumab with PDT and bevacizumab with PDT were equally effective, and there was no difference in the outcome measures between the two groups. Our findings are in agreement with the recently published CATT trial and IVAN study in which bevacizumab and ranibizumab did not differ significantly in improving the visual acuity.[7,8] Thus, even in combination with the PDT, the efficacy of the bevacizumab and ranibizumab appears to be similar. We also did not observe any difference in the adverse effects between the two groups. However, except for the lesion thickness in the Group B, the rest of the parameters measured on the OCT showed only a trend of improvement without any significant change. We attribute this to the PRN use of the injections. In the CATT trial, it has been shown that the results of the PRN groups for both ranibizumab and bevacizumab were inferior to the monthly treatment groups. Apparently, the PDT does not cover the periods of VEGF activity when the effect of the anti-VEGF agents has abated.[12]

Studies of intravitreal anti-VEGF monotherapies for CNV due to ARMD reveal that therapy must be frequently administered for a prolonged but unknown period to maintain the VA benefit.[13,14,15,16] Previous reports have demonstrated the beneficial effect of combination therapy on reducing the number of retreatment injections. In the DENALI[4] study, 20% of patients did not receive any further treatment postcombination therapy. In our study also, 26% of the patients did not receive any further treatment on long-term follow-up. In our study, the average treatment free interval in Group A was 6 months while in Group B, it was 4 months. This is very similar to the results of both DENALI[4] and MONT BLANC[12] studies which demonstrated a treatment-free interval of 4 months or more in 81% and 3 months or more in 95% of eyes, respectively. We attribute the longer interval of retreatment in Group A to the longer duration of action of bevacizumab.

Effectiveness of combination therapy in reducing the number of retreatment visits

This has been reported in the previous studies.[4,12,17] RADICAL[18] and TORPEDO[19] study groups demonstrated that significantly fewer retreatments were required in PDT with ranibizumab group than ranibizumab monotherapy group over a period of 2 years. In our study, 3 or more additional anti-VEGF injections were required only in 19% of the eyes while 26% required no additional treatment on long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

No significant difference was found in anatomical as well as functional visual outcome between bevacizumab and ranibizumab when used in combination along with PDT. Our study demonstrates that the visual acuity stabilization and gains in both the ranibizumab and bevacizumab combinations are similar and given the cost of therapy, the patient may be given more options to choose from.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Mr. Marutha Muthu Thenarasu, MSc, PGDPS, for his help with the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, Meuer SM, Huang GH. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam eye study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1767–79. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nirmalan PK, Katz J, Robin AL, Tielsch JM, Namperumalsamy P, Kim R, et al. Prevalence of vitreoretinal disorders in a rural population of southern India: The Aravind Comprehensive Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:581–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azad R, Chandra P, Gupta R. The economic implications of the use of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs in age-related macular degeneration. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:441–3. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.36479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser PK, Boyer DS, Cruess AF, Slakter JS, Pilz S, Weisberger A. DENALI Study Group. Verteporfin plus ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: Twelve-month results of the DENALI study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1001–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, Boyer DS, Kaiser PK, Chung CY, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DM, Michels M, Kaiser PK, Heier JS, Sy JP, Ianchulev T ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Two-year results of the ANCHOR study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:57–65.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IVAN Study Investigators. Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, Downes SM, Lotery AJ, et al. Ranibizumab versus bevacizumab to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration: One-year findings from the IVAN randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group. Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, Ying GS, Jaffe GJ, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: One-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials - TAP report. Treatment of age-related macular degeneration with photodynamic therapy (TAP) Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1329–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser PK. Visudyne in Occult CNV (VIO) Study Group. Verteporfin PDT for subfoveal occult CNV in AMD: Two-year results of a randomized trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1853–60. doi: 10.1185/03007990903038616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazic R, Gabric N. Verteporfin therapy and intravitreal bevacizumab combined and alone in choroidal neovascularization due to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen M, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lanzetta P, Wolf S, Simader C, Tokaji E, et al. Verteporfin plus ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: Twelve-month MONT BLANC study results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abraham P, Yue H, Wilson L. Randomized, double-masked, sham-controlled trial of ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: PIER study year 2. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:315–24.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Eldem B, Guymer R, Korobelnik JF, Schlingemann RO, Axer-Siegel R, et al. Efficacy and safety of monthly versus quarterly ranibizumab treatment in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: The EXCITE study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:831–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, Dubovy SR, Michels S, Feuer W, et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Year 2 of the PrONTO Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:43–58.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel PJ, Tufail A. for the ABC Trial Investigators. Optimizing individualized therapy with bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2012 doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31823f0ba3. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31823f0ba3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heier JS, Boyer DS, Ciulla TA, Ferrone PJ, Jumper JM, Gentile RC, et al. Ranibizumab combined with verteporfin photodynamic therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Year 1 results of the FOCUS Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1532–42. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.11.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datseris I, Kontadakis GA, Diamanti R, Datseris I, Pallikaris IG, Theodossiadis P, et al. Prospective comparison of low-fluence photodynamic therapy combined with intravitreal bevacizumab versus bevacizumab monotherapy for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30:112–7. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.833268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberg L, Leys A. Treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with a variable ranibizumab dosing regimen and one-time reduced-fluence photodynamic therapy: The TORPEDO trial at 2 years. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:943–56. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]