Abstract

Resveratrol is a naturally occurring polyphenol, possesses several pharmacological activities including anticancer, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antinociceptive, and antiasthmatic activity. Little is known about its hepatoprotective action mechanisms. This study was conceived to explore the possible protective mechanisms of resveratrol compared with the hepatoprotective silymarin in thioacetamide (TAA)-induced hepatic injury in rats. Thirty-two rats were equally divided into four groups; normal control (i), TAA (100 mg/kg) (ii), TAA + silymarin (50 mg/kg) (iii), and TAA + resveratrol (10 mg/kg) (iv). Liver function and histopathology, pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and apoptotic markers were examined. Data were analyzed using ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc test. Compared to TAA-intoxicated group, resveratrol mitigated liver damage, and inflammation as noted by less inflammatory infiltration, hydropic degeneration with decreased levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interferon-gamma by 78.83, 18.12, and 64.49%, respectively. Furthermore, it reduced (P < 0.05) alanine and aspartate aminotransferases by 36.64 and 48.09%, respectively, restored hepatic glutathione content and normalized superoxide dismutase and malondialdehyde levels. While it inhibited nuclear factor-kappa B, cytochrome 2E1, and enhanced apoptosis of necrotic hepatocytes via increasing caspase-3 activity. Our findings indicated that the potential hepatoprotective mechanisms of resveratrol are associated with inhibition of inflammation, enhancing the apoptosis of necrotic hepatocytes, and suppression of oxidative stress.

Keywords: Caspase-3, cytotoxicity, liver inflammation, pro-inflammatory cytokines, resveratrol

INTRODUCTION

Despite the prevalence of liver diseases worldwide with high morbidity and mortality rates, medical treatment is still inadequate. Corticosteroids and antiviral drugs are used to decrease liver diseases progression, yet they have known adverse effects.[1] A safe therapy to prevent this progression is still banging.

Thioacetamide (TAA)-induced hepatic injury is an important model; it perfectly mimics human chronic hepatic diseases.[2] Furthermore, the use of hepatocyte cultures are now well acceptable to examine the drug's safety and present a good alternative to whole animal experiments.[3] Upon liver injury, nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) is induced, leading to production of various inflammatory factors including interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).[4] NF-κB activation would contribute to massive hepatocytes death, inflammation, and activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) leading to fibrosis.[5] However, when NF-κB activation is inhibited, HSCs will undergo enhanced apoptosis.[6]

Modulation of hepatic inflammation and oxidative damage play an important role in protecting against associated morbid changes, thus study of compounds that could be useful as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents such as phenolic compounds is gaining more interest. Resveratrol (3,45 trihydroxystilbene) is a phytoalexin, naturally occurring polyphenol, possesses cardioprotective, neuroprotective, antidiabetic, and anti-asthmatic activities[7] and protects against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity.[8] This study evaluates the safety of resveratrol in comparison to the classic hepatoprotective silymarin in vitro using primary isolated hepatocytes. Moreover, to shed light on the possible mechanisms by which resveratrol could protect rats against TAA-induced liver injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Silymarin, Legalon® (Chemical Industries Development, Egypt). Resveratrol, Resveratrol Extra® (Pure Encapsulations Inc., Sudbury, MA, USA). Collagenase-IV, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and TAA (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., USA). Hank's Balanced Salt Solution with and without Ca2+/ Mg2+ and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Lonza, Bioproducts, Belgium). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, South America), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) kits (Spectrum, MDSS, Hannover, Germany). TNF-α, IL-6, and interferon-gamma (INF-γ) ELISA complete tests (Koma Biotech, Korea). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH) kits (Biodiagnostic, Egypt).

Animals

Male albino rats weighing 150 g were provided by the Schistosome Biological Supply Center of Theodor Bilharz Research Institute (TBRI), housed under standard conditions of temperature and humidity, with free access to food and water ad libitum. All experiments conducted after approved by the Institutional Review Board of TBRI.

Isolation and culture of primary hepatocytes

Hepatocytes were isolated using collagenase perfusion of liver[9] and were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% inactivated FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin maintained at 37°C/5% CO2. The cells viability was determined by fraction of cells excluding “trypan blue.” Hepatocytes (>85% viability) were seeded on 96-well collagen coated plates in 200 µl medium at a density of 5 × 103/well.

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide cytotoxicity assay

After 24 h incubation, the medium was replaced with 200 µl fresh medium and cells were treated with various concentrations (5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 300, and 500 µg/ml) of silymarin or resveratrol dissolved in 0.1% DMSO for 24 or 48 h. Hepatocytes with 0.1% DMSO were used as control. After each incubation period, 20 µl of 5 mg/ml MTT solution was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C/5% CO2. The culture medium was aspirated and formazin crystals were dissolved in 200 µl DMSO. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm and the background subtracted at 620 nm.[10] Two independent experiments using separately prepared hepatocytes were carried out.

Experimental design

Thirty-two rats were divided equally into four groups. Normal control (i) received the drug vehicle (cremophor-El). Rats injected intraperitonealy with TAA in a dose of 100 mg/kg once/week for four successive weeks (ii). Rats received either silymarin (iii) or resveratrol (iv) in a daily oral dose of 50 or 10 mg/kg, respectively, along with TAA for 1 month. Animals were sacrificed 24 h after the last dose of treatment by decapitation under light ether anesthesia. Blood samples were immediately collected and livers were dissected and divided into two parts, the first part was used for histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations and the second part (1 g) was homogenized (1:5 w/v) in ice-cold 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The homogenate was centrifuged at 7700 rpm and the supernatant was used for assay of oxidative stress markers.

Biochemical assays

Serum pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and INF-γ were assayed according to protocols provided by ELISA kits. Serum AST, ALT and hepatic GSH content, and SOD activity were estimated using kits as per the manufacturer instructions as well as malondialdehyde (MDA) level.[11]

Histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations

Five µm thick sections of paraffinized liver stained with hematoxylin and eosin were examined histopathologically under Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH 07745 Jena, Germany) with × 200 magnification power. For immunohistochemistry, liver paraffin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated on positive charged glass slides. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by incubation in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in absolute methanol for 30 min. Sections were incubated in 5% skimmed milk for 30 min at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave (700W) treatment in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 7.4) for 15 min. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-rat caspase-3, cytochrome 2E1 (CYP2E1), and NF-кB primary antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, USA) at dilutions of 1:100 1:150 and 1:150, respectively. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in secondary antibodies. A brown color develops after addition of 3-diaminobenzidine for 2–4 min, washed in distilled water and counter stained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 1 min at room temperature. The percent of positively stained brown nuclei (NF-кB) or brown cytoplasm (caspase-3 and CYP2E1) in 10 successive fields at magnification of ×200 was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Cell viability percentages were calculated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (San Diego, CA, USA), and data were statistically analyzed using paired Student's t-test. For in vivo study, data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed using ANOVA test followed by Tukey post hoc test (SPSS version 16.0, Chicago, IL, USA). P > 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In vitro cytotoxicity

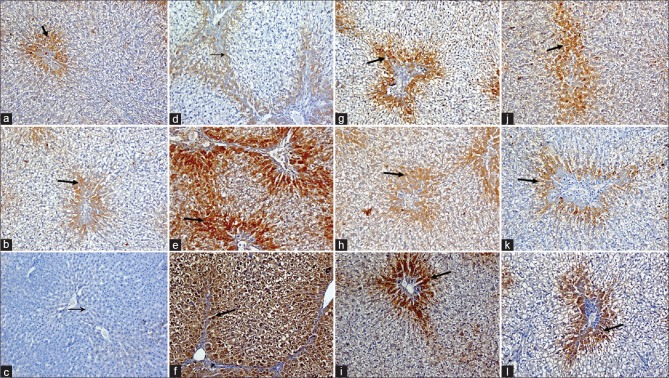

Results expressed as means of percentages of living cells compared to control indicated that silymarin and resveratrol did not reveal any toxic effect after 24 and 48 h [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Effect of various concentrations of silymarin or resveratrol on primary isolated hepatocytes viability after 24 and 48 h. Results are expressed as mean of percentages of living cells compared to control ± standard error of the mean.aP < 0.05 compared to 100% control cell viability

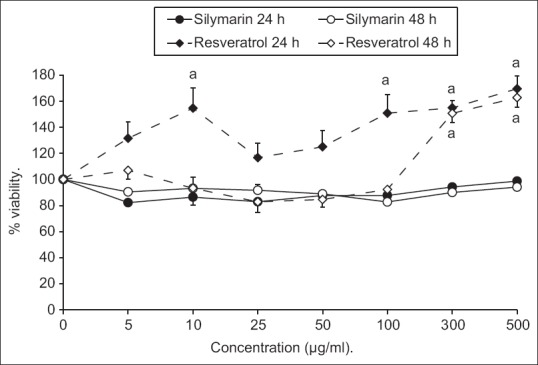

Effect of resveratrol on liver function, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress markers

The effects of resveratrol on all the biochemical parameters were shown in Table 1. A significant increase in serum ALT and AST by 113.74 and 105.98%, respectively, and in TNF-α, IL-6, and INF-γ by 550.3, 34.82, and 252.42%, respectively, was observed in TAA-intoxicated rats compared to normal control. Furthermore, MDA was significantly higher (95.1%) concomitant with depletion in GSH content and SOD activity by 62.01% and 60.76, respectively. Treatment with either silymarin or resveratrol significantly (P < 0.05) reduced ALT and AST compared to TAA group. Meanwhile, TNF-α, IL-6, and INF-γ were markedly reduced by the use of resveratrol or silymarin with the advantage of resveratrol in restoring INF-γ level to the normal rather than silymarin. The oxidative stress parameters were normalized in resveratrol-treated group, except GSH content.

Table 1.

Effect of resveratrol (10 mg/kg) or silymarin (50 mg/kg), on biochemical markers in rats with thioacetamide.induced hepatic injury

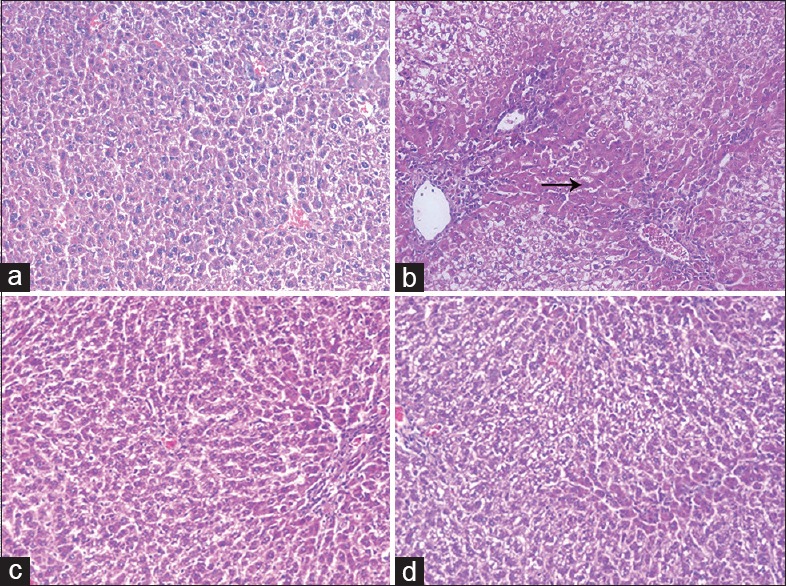

Effect of resveratrol on liver histopathology

Liver sections of normal rats showed normal cellular architecture [Figure 2a]. In contrast, TAA-intoxicated rats' liver showed severe degenerative changes, hydropic degeneration, necrosis, and infiltration of inflammatory cells [Figure 2b]. Meanwhile, liver sections of silymarin or resveratrol-treated groups showed an almost normal pattern of liver tissue, decreased hydropic degeneration with lymphocyte infiltration and recovery from necrosis [Figure 2c and d].

Figure 2.

Histopathological examination of liver sections from (a) normal rats showing normal hepatic architecture, (b) thioacetamide-intoxicated rats showing severe disturbances in hepatic architecture and portal tract inflammation with severe lymphocyte infiltration and focal spotty necrosis (black arrow), (c) silymarin-treated rats showing almost normal hepatic architecture with mild dilation of sinusoids and lymphocyte infiltration, and (d) resveratrol-treated rats showing normal hepatic architecture and mild number of chronic inflammatory cells infiltration (H and E, ×200)

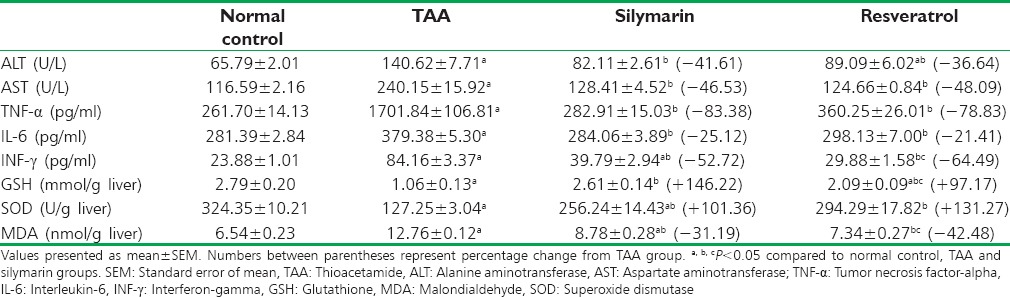

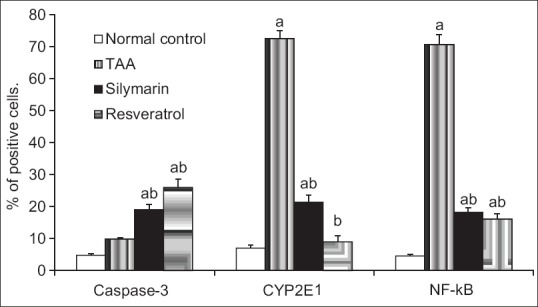

Effect of resveratrol on caspase-3, cytochrome 2E1, and nuclear factor-kappa B

TAA injection did not produce significant change in caspase-3, with a significant increase in NF-кB and CYP2E1 positive cells (15.34, 10.34 fold, respectively) when compared to normal rats [Figures 3 and 4]. Treatment with resveratrol or silymarin significantly reduced both NF-кB (77.33%, 74.22%, respectively) and CYP2E1 (87.57%, 70.44%, respectively) compared to TAA-intoxicated rats, whereas increased the percent of caspase-3 positive stained cells significantly (165.31%, 93.87%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for caspase-3, cytochrome 2E1, and nuclear factor-kappa B in rat liver sections. Normal rats (a, b and c, respectively) showing few number of positive hepatocytes for caspase-3 and cytochrome 2E1 as brownish cytoplasmic stain and nuclear factor-kappa B as brownish nuclear stain (black arrows), thioacetamide-intoxicated rats (d, e, and f, respectively) showing few positive hepatocytes (centrilobular and periportal areas) with mild density for caspase-3, and many positive hepatocytes (centrilobular and periportal areas) with severe density cytochrome 2E1 and nuclear factor-kappa B (black arrows), meanwhile, silymarin (g, h, and i, respectively) and resveratrol (j, k, and l, respectively)-treated rats showing many positive hepatocytes (periportal areas) with moderate density for caspase-3 and few positive hepatocytes (periportal areas) with mild density cytochrome 2E1 and nuclear factor-kappa B (black arrows), (IHC, DAB, ×200)

Figure 4.

Percentage of positively stained brown cytoplasm (caspase-3, cytochrome 2E1) or brown nuclei (nuclear factor-kappa B), in 10 successive fields.a,bP < 0.05 compared to normal control and thioacetamide groups

DISCUSSION

On primary isolated hepatocytes cultures, silymarin and resveratrol showed no toxicity after 24 and 48 h incubations. Meanwhile, resveratrol increased significantly cell viability relative to control cells. This finding might be related to the powerful antioxidant effect of resveratrol resulting in less death of primary hepatocytes because of normal turnover with release of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This is in accordance with those authors,[12] who reported resveratrol-related induction of phase-II and antioxidant enzymes in cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, resveratrol significantly reduced ceramide content in plasma membranes of senescent hepatocytes, known to accumulate with the onset of aging-associated inflammation.[13]

It is known that high levels of ROS induce cell damage and are involved in several human pathologies including liver cirrhosis and fibrosis.[14] Moreover, GSH plays a key role in detoxifying the reactive toxic metabolites of many toxins, whereas MDA is the end product of lipid peroxidation.[15] Consequently, the use of compounds having antioxidant properties may protect or mitigate many diseases associated with ROS. In this study, resveratrol showed almost normalized levels of SOD and MDA, with silymarin normalized GSH content.

Concerning hepatic inflammation herein, resveratrol normalized pro-inflammatory cytokines levels, whereas silymarin normalized only TNF-α and IL-6. This was evident by the less numbers of chronic inflammatory cells and diminished hepatic necrosis as shown histopathologically. It is worthy noted that levels of TNF-α and IL-6 are elevated in both infiltrating inflammatory cells and hepatocytes in chronic liver injuries including viral or alcoholic liver diseases, hepatitis, ischemia, and biliary obstruction.[16] In this context, Rivera et al.[17] reported that resveratrol may help in stabilization of hepatocytes membrane accelerating regeneration of parenchymal cells, thus protecting against membrane fragility and decreasing leakage of liver markers into the circulation of CCl4-intoxicated rats.

Resveratrol showed a powerful hepatoprotective activity than silymarin as evidenced by the enhanced decrease in CYP2E1 positive cells, which play a vital role in the suppression of conversion of TAA to its reactive toxic metabolite TASO2 that initiates necrosis by covalently binding to liver macromolecules.[18]

Inflammation and apoptosis are always associated with hepatic injuries that can induce an immune response, activate HSCs, and inhibit extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation.[19] Moreover, when hepatocytes undergo apoptosis and fail to regenerate, the apoptotic hepatocytes are replaced by abundant ECM.[20] Our study, therefore, stressed measuring NF-κB and caspase-3 as important factors in hepatic injury. Importantly, results of this investigation indicated that resveratrol decreased significantly NF-κB, which in turn, further downregulated activation of HSCs, hence forced activated HSCs to undergo apoptosis. Meanwhile, TAA-induced hepatic injury did not show significant difference in the regulatory level of apoptosis when compared to normal control. Fortunately, resveratrol enhanced apoptosis as expressed by higher percent of caspase-3 activity. This upregulation may be to remove necrotic damaged hepatocytes or/and activated HCSs leading to decrease in all signs of liver damage and inflammation.

CONCLUSION

Resveratrol and silymarin showed anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity, yet resveratrol revealed a more pronounced potential effects. Our findings indicated that resveratrol regulate liver injury through caspase-3 activation and inhibition of NF-κB and CYP2E1, which play an important role in suppression of TAA biotransformation to its toxic metabolite. Therefore, resveratrol could be a good safe candidate drug in the suppression of liver injury.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the internal research project 101/A for basic and applied research, a grant from Theodor Bilharz Research Institute.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:474–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie Y, Wang G, Wang H, Yao X, Jiang S, Kang A, et al. Cytochrome P450 dysregulations in thioacetamide-induced liver cirrhosis in rats and the counteracting effects of hepatoprotective agents. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:796–802. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.043539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van de Bovenkamp M, Groothuis GM, Meijer DK, Olinga P. Liver fibrosis in vitro: Cell culture models and precision-cut liver slices. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007;21:545–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwabe RF, Schnabl B, Kweon YO, Brenner DA. CD40 activates NF-kappa B and c-Jun N-terminal kinase and enhances chemokine secretion on activated human hepatic stellate cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:6812–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen H, Sheng L, Chen Z, Jiang L, Su H, Yin L, et al. Mouse hepatocyte overexpression of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) triggers fatal macrophage-dependent liver injury and fibrosis. Hepatology. 2014;60:2065–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.27348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anan A, Baskin-Bey ES, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Shah VH, Gores GJ. Proteasome inhibition induces hepatic stellate cell apoptosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:335–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.21036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saiko P, Szakmary A, Jaeger W, Szekeres T. Resveratrol and its analogs: Defense against cancer, coronary disease and neurodegenerative maladies or just a fad? Mutat Res. 2008;658:68–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sener G, Toklu HZ, Sehirli AO, Velioglu-Ogünç A, Cetinel S, Gedik N. Protective effects of resveratrol against acetaminophen-induced toxicity in mice. Hepatol Res. 2006;35:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–83. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Z, Li Y. Potent induction of cellular antioxidants and phase 2 enzymes by resveratrol in cardiomyocytes: Protection against oxidative and electrophilic injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;489:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lançon A, Delmas D, Osman H, Thénot JP, Jannin B, Latruffe N. Human hepatic cell uptake of resveratrol: Involvement of both passive diffusion and carrier-mediated process. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:1132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu D, Zhai Q, Shi X. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cell responses. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S26–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Recknagel RO, Glende EA, Jr, Briton RS. Free radical damage and lipid peroxidation. In: Meeks RG, editor. Hepatotoxicology. Florida: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 401–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández-Muñoz I, de la Torre P, Sánchez-Alcázar JA, García I, Santiago E, Muñoz-Yagüe MT, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits collagen alpha 1(I) gene expression in rat hepatic stellate cells through a G protein. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:625–40. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera H, Shibayama M, Tsutsumi V, Perez-Alvarez V, Muriel P. Resveratrol and trimethylated resveratrol protect from acute liver damage induced by CCl4 in the rat. J Appl Toxicol. 2008;28:147–55. doi: 10.1002/jat.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chilakapati J, Korrapati MC, Shankar K, Hill RA, Warbritton A, Latendresse JR, et al. Toxicokinetics and toxicity of thioacetamide sulfoxide: A metabolite of thioacetamide. Toxicology. 2007;230:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu L, Kong M, Han YP, Bai L, Zhang X, Chen Y, et al. Spontaneous liver fibrosis induced by long term dietary Vitamin D deficiency in adult mice is related to chronic inflammation and enhanced apoptosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;93:385–94. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duval F, Moreno-Cuevas JE, González-Garza MT, Rodríguez-Montalvo C, Cruz-Vega DE. Liver fibrosis and protection mechanisms action of medicinal plants targeting apoptosis of hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2014;2014:373295. doi: 10.1155/2014/373295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]