Abstract

Aims and background

Exfoliated cells in human stool offer excellent opportunities to non-invasively detect molecular markers associated with colorectal tumorigenesis, and to evaluate the effects of exposures to exogenous and endogenous carcinogenic or chemopreventive substances. This pilot study investigated the feasibility of determining DNA methylation and RNA expression simultaneously in stool specimens treated with a single type of nucleic acid preservatives.

Methods

Stool specimens from 56 volunteers that were preserved up to a week with RNAlater were used in this study. Bisulfite sequencing was used to determine methylation at 27 CpG loci on the estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) promoter. Taqman assay was used for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions to measure cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mRNA expression. Subjects’ basic demographic and other selected risk factors for colorectal cancer were captured through questionnaires and correlated with the levels of these markers.

Results

Less than 10% of the samples failed in individual assays. Overall, 24.0% of the CpG loci on the ESR1 promoter were methylated. COX2 expression and alcohol use were positively correlated; an inverse association was present between EGFR expression and cigarette smoking; and subjects using anti-diabetic medication had higher ESR1 methylation. In addition, higher EGFR expression levels were marginally associated with history of polyps and family history of colorectal cancer.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that simultaneous analyses for DNA and RNA markers are feasible in stool samples treated with a single type of nucleotide preservatives. Among several associations observed, the association between EGFR expression and polyps deserves further investigation as a potential target for colorectal cancer screening. Larger studies are warranted to confirm some of our observations.

Keywords: stool test, DNA, RNA, colorectal cancer

Introduction

It has been estimated that approximately 1.5 million human colonic epithelial cells can be isolated per gram of human stool1,2. Thus, exfoliated cells in stool offer excellent opportunities to non-invasively detect molecular markers associated with colorectal tumorigenesis, as well as to evaluate the effects of luminal and systemic exposures of colorectal epithelial cells to exogenous and endogenous carcinogenic or chemopreventive substances3,4.

Most stool-based screening tests for molecular markers utilize fresh or frozen stool specimens. This requires prompt transfer of sample from the subject’s home to a testing laboratory, which may not always be practical. However, new technologies have recently become available to preserve DNA and RNA for a period of time at room temperature, so that immediate processing is no longer necessary5,6. Such technologies may greatly facilitate screening tests and epidemiological studies. In fact, mutations, microsatellite instability, and aberrant promoter methylation in several candidate genes have already been introduced in colorectal cancer screening3,7,8. In addition, methylation in other genes, including the estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1), are suggested to serve as a marker for both aging and colorectal cancer9. A number of genes that are overexpressed in colorectal cancer tissue also represent potential targets for new therapy and RNA-based screening. Of particular interest are cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), which has already been tested in several studies for screening8,10, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), for which an anti-EGFR therapy has been approved by the FDA for advanced colorectal cancer11. Importantly, aberrant promoter methylation and COX2 and EGFR expressions have been shown to be influenced by environmental factors12-16 that are associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer, e.g., alcohol intake17 and cigarette smoking18,19, as well as with reduced risk, such as aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use20.

Although some clinical studies have employed DNA preservatives for stool testing7,21-23, media that can preserve both DNA and RNA are highly desirable in order to examine different types of markers simultaneously. Despite the perceived difficulty in recovering good quality RNA from stool samples, our laboratory recently reported the use of commercially available preservatives that enabled analysis of mRNA for a specific gene in most stool samples tested5. In that study, we compared comprehensively several commercially available preservatives in both DNA and RNA quantity and quality as well as in PCR inhibitory effects in order to choose one that works best for downstream DNA and mRNA analyses5,6. The aims of this cross-sectional study were (i) to test the feasibility of a selected preservative, RNAlater, to quantify fecal ESR1 promoter methylation and EGFR and COX2 mRNA expression; and (ii) to examine whether these molecular markers were affected by age, gender, alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, regular aspirin use, colorectal polyp history, and family history of colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The subjects included in this study were individuals aged 48 or older or those younger than 48 with a history of polyps. Ineligibility criteria included recent use (within a month) of oral antibiotics (due to their effects on intestinal bacteria) or medications known to affect methylation (including some antineoplastic, antirheumatic, and anti-AIDS agents such as 5-FU derivatives, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and AZT, and other medications, such as hydralazine and procainamide), recent history of an infectious type of diarrhea, or a history of major colorectal surgery (i.e., hemicolectomy or total colectomy). Those with a history of colorectal cancer were also ineligible for this study. The study comprised 2 phases: the initial phase for the development and validation of fecal specimen collection, processing, and stool marker assays, and the second phase for application of a single selected stool collection/processing method to community volunteers. The first phase involved 10 patients being evaluated at a vascular clinic, the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center (Detroit, MI), that have been described in more detail elsewhere6; the second phase involved 53 community volunteers who were recruited through flyers and personal referral. Among the 63 study subjects, 12 reported a previous diagnosis of colorectal polyps. The research protocol was approved by the human investigation committees of the Wayne State University and the VA Medical Center, and signed informed consent was obtained from each study participant.

Sample collection and processing

The sample collection and processing procedures for the initial phase have been described previously5,6. Briefly, fresh stool samples were collected and tested after storage with several commercially available preservatives for 5 days, in comparison with stool samples immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Based on these results, we chose RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) as the preservative to be used in the second phase. Although RNAlater is a non-toxic chemical, it is an irritant. Thus, to minimize the risk of accidental exposure for prospective participants, we invented a special fume-free device that enabled subjects to mix a stool aliquot with the solution without contacting or inhaling the chemical (International Patent Appln. No. PCT/US 08/1089). The device contains 5 mL of RNAlater solution, and a collection spoon with an ejectable tip to hold an approximately 0.2 g stool aliquot. Two kits were provided to each participant with instructions for sending collected samples back to our laboratory by priority mail in leak-free plastic bags in an envelope that we provided. Upon receipt, samples were centrifuged, and pellets were transferred to -80 °C. For each subject, total RNA was extracted from 1 of the 2 samples using the RNA PowerSoil™ (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) method, and DNA was extracted by a Qiagen Stool kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from the second sample, except in the case of 1 participant from whom only 1 satisfactory sample was received which was processed for RNA only. All extraction procedures followed original manufacturers’ standard procedures for RNA and human DNA extraction.

Data concerning subjects’ medical history, family history, smoking, drinking, body weight and height were obtained through structured questionnaires. All subjects in phase 1, and 8 subjects in phase 2 were interviewed in person to complete the questionnaires. Nine subjects in phase 2 were interviewed over the telephone, while the remainder of the subjects in phase 2 chose to complete the questionnaires by themselves at home and to return them by mail. The information about subjects’ characteristics were not shared with laboratory personnel who performed the assays to ensure unbiased assessments.

DNA methylation assays

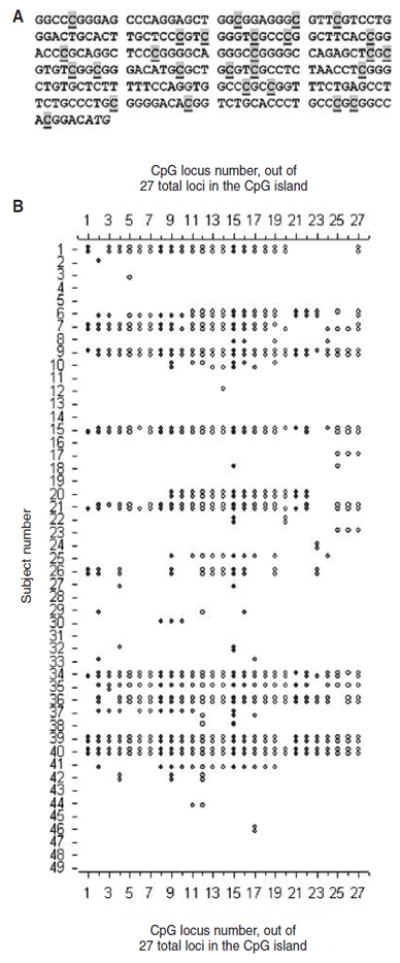

DNA (2 μg) was denatured in 0.3 M NaOH, treated with 3 M sodium metabisulfite and 0.5 M hydroquinone for 20 heating cycles (95 °C 30 s alternating with 50 °C 15 min), then purified, desulfonated, and precipitated in 40 mM sodium acetate in 96% ethanol at -80 °C. In order to increase specificity and sufficient amplification of this human DNA target, we used nested PCR to amplify the 5’-untranslated region at bases -247 to -1 upstream from the ATG start codon of ESR1, which contained 27 CpG sites (Figure 1A). Primers in the first-round amplification were LP-ER-403 (5’-GAG-TGA-TGT-TTA-AGT-TAA-TGT-TAG-GGT-AAG-3’) and RP-ER-403 (5’-ATC-TAA-TAC-AAT-AAA-ACC-AC-CCA-AAT-ACT-3’), and those in the second round were LP-ER-290 (5’-GAG-ATT-AGT-ATT-TAA-AGT-TGG-AGG-TT-3’) and RP-ER- 290 (5’-AAT-ATA-AAA-AAT-CAT-AAT-CAT-AAT-CC-3’). Purified bisulfite-treated DNA or PCR product from the preceding round was amplified using 10 pmol each of primers, 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase, 1.25 mM MgCl2, dNTPs and PCR buffer (Applied Biosystems) in a final volume of 50 μL. The first-round PCR thermocycle consisted of 93 °C for 3 min initial denaturation, 40 cycles of amplification (45 s 93 °C, 45 s 55 °C primer annealing, 1 min 72 °C elongation), and 7 min final 72 °C elongation. Second-round PCR was identical except that the annealing step was at 50 °C.

Figure 1.

A) CpG island analyzed in this paper. The 27 potentially methylated CpG sites in the 5’-untranslated genomic sequence of ESR1 are highlighted and underlined. The italic ATG is the translation start codon of the gene. B) Methylation at the 27 loci illustrated in 1A for 2 clones of DNA sequences derived from each of 49 subjects. Symbols indicate a methylated CpG; blanks denote no methylation.

The PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels, purified with a Rapid Gel Extraction System® (Marligen Biosciences, Inc, Rockville, MD, USA), and then cloned for sequencing using the TOPO TA Cloning® kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Two clones were analyzed for each sample. After confirming the presence of the target DNA region in each amplicon by reamplification, DNA was purified and sequenced. The presence of methylation at each of the 27 CpG sites was determined by comparing the resultant sequences with the reference human genomic sequence, scoring sites as methylated or non-methylated according to the presence of C or T, respectively. DNA extracted from MCF-7 and SW-48 cell lines were used as negative and positive controls.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions (qRT-PCR)

The expression levels of 3 genes were quantified by qRT-PCR in 3 samples from the first phase and 28 from the second phase that had at least 0.5 μg of total RNA left (n = 31). This reduction in the sample size was partly due to heavy usage of some of the samples (particularly those in phase 1) for other purposes. cDNA was prepared from total RNA isolated from stool using the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The cDNA was preamplified using the TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix Kit with pooled TaqMan assay mixes for PTGS2, EGFR, and RPLP0 (the gene for protein P0 of the large ribosomal subunit, considered a housekeeping gene for internal reference control), for 10 cycles. Expression analysis for PTGS2, EGFR, and RPLP0 were run using TaqMan assay mixes. The assays were run in triplicate at 3 concentrations (1:5, 1:10 and 1:20 dilution) with no template controls on an AB7900. PCR efficiencies for each primer set were assessed by changes in threshold cycle numbers by 2-fold dilution specified above. The mean change by dilution was almost identical for the 3 genes, 1.0349 for EGFR, 09968 for COX2, and 1.0987 for RPLP0, and little different from the expected value, 1.000. All reactions were run with standard conditions as per manufacturers’ protocols.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented for each stool marker after averaging 2 methylation frequencies from bisulfite sequencing and 9 repeated measures (triplicate assays at the 3 concentrations) for Ct values. Relative quantification of gene expression was performed by computing the difference in PCR threshold cycle numbers (Ct values) between RPLP0 and the target genes (PTGS and EGFR). Levels of each marker were then categorized into 3 levels (approximate tertiles); negative, low and high, based on the overall distribution. The prevalence (%) of the selected characteristics of the study subjects was calculated by the level of each stool marker and the distributions of these characteristics by stool marker level were tested by Fisher’s exact test. In addition, if the selected characteristics were originally given as continuous values, Spearman’s correlation co-efficients between the stool markers and those covariates were calculated. All P values were 2 sided.

Results

Among the 52 samples tested for ESR1 methylation, 3 failed to amplify the ESR1 gene after bisulfite treatment, and 2 of the 31 RNA samples tested failed to amplify RPLP0. Thus, the effective sample size was 49 for DNA methylation, and 29 for RNA expression assay (Table 1). Altogether, there were 55 study subjects aged 27-73 years (median 60 years) including 10 with a history of polyps. For the bisulfite sequencing analysis of ESR1 methylation, a total of 2,646 loci were sequenced for the 49 subjects, and 634 (24.0%) were found to be methylated. A high intra-individual (clone) correlation was present among methylated loci, i.e., methylation clustered within individuals/clones (Figure 1B). The median number of methylated CpG sites out of the 27 tested for each subject was 1.5, while 9 subjects had average values of 20 or above. EGFR transcript levels were higher than those of RPLP0 for most of the RNA samples. COX2 was expressed in approximately two-thirds of the samples, and the median expression level was lower than that of RPLP0 (Table 1).

Table 1. Numbers of study subjects included and median and range of the test results for each marker.

| Markers | No. tested | No. failed | Effective sample size | No. with undetectable levels | Median* | Range of detectable levels* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR1 methylation | 52 | 3 | 49 | 14 | 1.5 | 0.5 - 27.0 |

| EGFR expression | 31 | 2 | 29 | 2 | 0.556 | -2.398-4.143 |

| COX2 expression | 31 | 2 | 29 | 10 | -0.942 | -3.049-4.874 |

| Total | 56 | 55 | (Age 27-73, median 60 years, 53% male) | |||

Values are expressed as the number of detected methylation sites out of the 27 loci for ESR1 and differences in threshold cycle numbers (Ct values) from a housekeeping gene for EGFR and COX2.

Tables 2-4 present the associations between these molecular markers and subjects’ characteristics. For ESR1 methylation (Table 2), the average number of methylated CpG islands out of the 27 loci were grouped as follows; negative: 0 and 0.5 (borderline positive), low: 1-9.5 loci, and high: equal or above 10 loci. There were no subjects whose samples yielded values between 6.5 and 10. Participants’ demographics, history of polyps or family history of colorectal cancer were not associated with the level of ESR1 methylation.

Table 2. Prevalence (%) of selected characteristics among 49 subjects according to ESR1 promoter methylation status.

|

ESR1 methylation*

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Definition | Negative (n = 17) | Low (n = 19) | High (n = 13) | P value for Fisher’s exact test | P value for Spearman correlation |

| Age | ≥60 | 58.8 | 47.4 | 53.9 | 0.826 | 0.274 |

| Gender | Male | 47.1 | 52.6 | 61.5 | 0.720 | - |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| Ever | 47.1 | 57.9 | 46.2 | 0.817 | - | |

| ≥20 pack-years | 29.4 | 26.3 | 15.4 | 0.707 | 0.574 | |

| Alcohol | ≥1 drin k/day | 52.9 | 47.4 | 53.9 | 1.000 | 0.678 |

| Colorectal polyp | 17.7 | 21.1 | 15.4 | 1.000 | - | |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | 5.9 | 21.1 | 0.0 | 0.198 | - | |

| Regular aspirin use | 47.1 | 26.3 | 38.5 | 0.459 | - | |

Negative <1, Low 1.0-9.5, High ≥10 methylated out of 27 CpG loci.

Table 4. Prevalence (%) of selected characteristics among 29 subjects according to COX2 expression levels.

| Cox2 expression*

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Definition | Negative (n = 10) | Low (n = 9) | High (n = 10) | P value for Fisher’s exact test | P value for Spearman correlation |

| Age | ≥60 | 30.0 | 55.6 | 40.0 | 0.575 | 0.320 |

| Gender | Male | 69.7 | 55.6 | 60.0 | 0.893 | - |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| Ever | 80.0 | 44.4 | 70.0 | 0.296 | - | |

| ≥20 pack-y ears | 30.0 | 11.1 | 40.0 | 0.450 | 0.985 | |

| Alcohol | ≥1 drink/day | 30.0 | 33.3 | 80.0 | 0.061 | 0.026 |

| Colorectal polyp | 20.0 | 11.1 | 30.0 | 0.847 | - | |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | 10.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 0.754 | - | |

| Regular aspirin use | 0.0 | 66.7 | 30.0 | 0.005 | - | |

Negative: no expression, Low: lower than a housekeeping gene, High; higher than a housekeeping gene.

For EGFR (Table 3), the expression levels were grouped into those less than RPLP0, those 0 to 1.5 Ct units greater than RPLP0, and those more than 1.5 Ct units greater than RPLP0.1.5 Ct units change may be interpreted as ~2.82 fold change when PCR efficiencies are exactly the same for a target and a reference gene. The proportion of subjects who had ever smoked tended to decrease with EGFR expression levels, and the correlation between EGFR expression levels and the number of pack-years of cigarette smoking was statistically significant (P = 0.046). In addition, we observed marginally significant associations between higher expression levels and history of polyps (P = 0.050) and family history of colorectal cancer (P = 0.089).

Table 3. Prevalence (%) of selected characteristics among 29 subjects according to EGFR expression levels.

|

EGFR expression*

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Definition | Low (n = 10) | Interme diate (n = 9) | High (n = 10) | P value for Fisher’s exact test | P value for Spearman correlation |

| Age | ≥60 | 40.0 | 55.6 | 30.0 | 0.575 | 0.873 |

| Gender | Male | 60.0 | 66.7 | 60.0 | 1.000 | - |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| Ever | 90.0 | 66.7 | 40.0 | 0.066 | - | |

| ≥20 pack-years | 40.0 | 33.3 | 10.0 | 0.344 | 0.046 | |

| Alcohol | ≥1 drin k/day | 40.0 | 55.6 | 50.0 | 0.897 | 0.066 |

| Colorectal polyp | 0.0 | 44.4 | 20.0 | 0.050 | - | |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | 0.0 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 0.089 | - | |

| Regular aspirin use | 30.0 | 33.3 | 30.0 | 1.000 | - | |

Low: negative or lower than a housekeeping gene, Intermediate: 0 to 1.5 Ct units greater expression, High: more than 1.5 Ct units greater expression than a housekeeping gene.

The proportion of subjects who consumed at least 1 alcoholic drink per day tended to be higher in subjects expressing COX2, particularly in subjects whose samples yielded a high COX2 level (i.e., higher than RPLP0) (Table 4). The correlation coefficient between COX2 expression and the number of alcoholic drinks consumed per week by the subject was also statistically significant (P = 0.026). In addition, regular aspirin users (3 or more times per week) were more common among subjects expressing COX2 (P = 0.005). Finally, there was a marginally significant correlation (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.366, P = 0.051) between EGFR and COX2 expression. None of these correlated with ESR1 methylation.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that fecal samples collected in a commercially available nucleic acid preservative are adequate for testing DNA methylation and gene expression. A recently invented device for participants to self-collect, preserve, and mail fecal samples safely was used reliably by more than 50 subjects. Moreover, significant correlations between expression of EGFR and COX2 and various aspects of participants’ medical histories, smoking, and alcohol use were observed.

ESR1 was chosen for methylation analysis for healthy volunteers in this study, because its hypermethylation has been associated not only with colorectal tumors but also with aging9,24,25. However, no association with age was observed in our study. This may reflect the relatively narrow age range of our subjects since our study population consisted of individuals generally recommended for colorectal cancer screening. Because of this study design, all subjects were between 48 and 73 years old, except for one subject who was 27 years old but had a history of polyps. Alternatively, as most earlier reports were based on gastrointestinal disease or surgery clinics, age-related gastrointestinal pathologies may have confounded these associations with age. Studies have revealed that methylation status in specific gene promoters is affected by an assortment of environmental factors, but our study found little evidence of an effect of these environmental factors on ESR1 promoter methylation in exfoliated gastrointestinal cells. These discrepancies may arise from differences in tissues (normal vs tumor) and genes analyzed12-16.

EGFR is a member of the tyrosine kinase family of cell surface receptors that play key roles in regulating proliferation, differentiation and transformation of cells in many tissues. EGFR overexpression and increased tyrosine kinase activities have been associated with many malignancies including colorectal cancer26 and its precursor lesions such as colorectal polyps, and ulcerative colitis27. Thus, our observation that subjects reporting a history of colorectal polyps tended to exhibit higher EGFR expression in their exfoliated cells may have significant clinical implications. In addition, Brandt et al. reported that a polymorphic repeat sequence in the EGFR gene, leading to EGFR overexpression, was associated with a family history of cancer28, consistent with our observation of a greater prevalence of a family history of colorectal cancer among individuals with higher EGFR expression. The finding that smoking was a negative predictor of EGFR expression is intriguing in view of growing observations that non-smokers are more responsive to anti-EGFR therapies for non-small cell lung cancer than smokers29-33. Non-smokers are also more likely to display EGFR activation34 and mutations31,35-38 that lead to gene amplification and increased sensitivity to anti-EGFR agents39,40, and increased gene copy numbers31,41. Although the data specific to colorectal cancer outcome by smoking status are limited, the importance of EGFR copy number for clinical response to anti-EGFR treatment for colorectal cancer has previously been recognized42.

Increased COX2 expression was associated with alcohol drinking and regular aspirin use in our study. The association with alcohol intake is intriguing, as alcohol intake has been convincingly associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, especially for men17. In support of this association, increased cell regeneration and proliferation has been observed in experimental animals treated with ethanol as well as in chronic alcoholic patients43-45. These effects of alcohol have been hypothesized to be medicated through prostaglandin production (via COX), lipid peroxidation, generation of reactive oxygen species, and proinflammatory cytokine induction17,46,47. The increase in COX2 expression among regular aspirin users was unexpected. However, since aspirin inhibits COX2 activity at a post-translational level20, aspirin may drive gene expression in a compensatory fashion if there is an underlying disease leading to regular aspirin use. Because of the widespread use of this class of medications, caution should be exercised in evaluating COX2 expression data as a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening10.

This study has several limitations. First, we are fully aware that the sample size of this study is small and thus relates the low statistical power for detecting a modest effect size. Inadequate statistical power may also account for the lack of an observed statistical association between the extent of ESR1 methylation and covariates studied. On the other hand, there is a high likelihood that some of the associations observed in this study were chance findings due to multiple comparisons. Apparently, the associations found in our study need to be confirmed with larger samples as well as in independent populations. In fact, this study was designed to serve as a pilot to develop methodology for larger population studies.

Second, only 2 colonies were cloned for quantifying the degree of ESR1 methylation for each subject. Analysis of more colonies per sample could have more accurately reflected quantitative changes in a larger number of exfoliated cells. Furthermore, although DNA and RNA preservation and extraction methods were adequate to obtain measurements for most subjects, some degradation did still occur, and this could be improved. In the present study, several adjustments were important for ensuring the success of our analyses. For instance, for DNA methylation analysis, we found that amplifications were more robust and reproducible targeting sequences of 300 bp or shorter (data not shown). This constrained choices of CpG islands. The bisulfite sequencing protocol is also highly labor intensive. For further studies on genes more closely related to colorectal cancer, higher throughput methods, e.g., Taqman quantitative methylation-specific PCR, pyrosequencing, and MALDI-TOF48,49, need to be developed. To compensate for low yields of human RNA, samples were subjected to a pre-amplification process after reverse transcriptase reactions. The use of different RNA pre-amplification technologies50 may maximize the potential of these degraded samples.

Finally, our data concerning family history and history of polyps were self-reported, not confirmed by medical records. Thus, a certain degree of misclassification of family history may be present51. In addition, polyps could not be histologically defined and thus included hyperplastic polyps beside adenoma, although these polyps have been acknowledged as a high risk lesion for colorectal cancer52.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that simultaneous analyses for DNA and RNA markers are feasible in stool samples treated with a single type of nucleotide preservatives. This also provides promising information to advance the use of stool markers for identifying or monitoring high-risk individuals and for early detection of colorectal cancer. Specifically, EGFR expression in exfoliated cells in stool samples deserves further investigation as a potential target for colorectal cancer screening, while caution should be exercised in interpreting the data on COX2 expression. Larger studies are warranted to confirm some of the observed associations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Research Enhancement Program of Wayne State University. The authors thank Ms Ann Bankowski for study subject enrollment and for data and sample collection, and Ms Christina Haska for technical assistance in the development of methylation assays.

References

- 1.Iyengar V, Albaugh GP, Lohani A, Nair PP. Human stools as a source of viable colonic epithelial cells. FASEB J. 1991;5:2856–2859. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.13.1655550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desilets DJ, Davis KE, Nair PP, Salata KF, Maydonovitch CL, Howard RS, Kikendall JW, Wong RK. Lectin binding to human colonocytes is predictive of colonic neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborn NK, Ahlquist DA. Stool screening for colorectal cancer: Molecular approaches. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:192–206. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis CD. Use of exfoliated cell from target tissues to predict responses to bioactive food components. J Nutr. 2003;133:1769–1772. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Y, Majumdar APN, Nechvatal JM, Ram JL, Basson MD, Heilbrun LK, Kato I. Exfoliated cells in stool: A source for RT-PCR based analysis of biomarkers of gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:455–458. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nechvatal JM, Ram JL, Basson MD, Namprachan P, Niec SR, Badsha KZ, Matherly LH, Majumdar AN, Kato I. Fecal collection, ambient preservation, and DNA extraction for PCR amplification of bacterial and human markers from human feces. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;72:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itzkowitz SH, Jandorf L, Brand R, Rabeneck L, Schroy PC, 3rd, Sontag S, Johnson D, Skoletsky J, Durkee K, Markowitz S, Shuber A. Improved fecal DNA test for colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung WK, To KF, Man EP, Chan MW, Hui AJ, Ng SS, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Detection of hypermethylated DNA or cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA in fecal samples of patients with colorectal cancer or polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1070–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Issa JP, Ottaviano YL, Celano P, Hamilton SR, Davidson NE, Baylin SB. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet. 1994;7:536–540. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanaoka S, Yoshida K, Miura N, Sugimura H, Kajimura M. Potential usefulness of detecting cyclooxygenase 2 messenger RNA in feces for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:422–427. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallböhmer D, Zhang W, Gordon M, Yang DY, Yun J, Press OA, Rhodes KE, Sherrod AE, Iqbal S, Danenberg KD, Groshen S, Lenz HJ. Molecular determinants of cetuximab efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3536–3544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Engeland M, Weijenberg MP, Roemen GMJM, Brink M, de Bruine AP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA, Baylin SB, de Goeij AFPM, Herman JG. Effects of dietary folate and alcohol intake on promoter methylation in sporadic colorectal cancer: the Netherlands Cohort Study on Diet and Cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3133–3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zochbauer-Muller S, Lam S, Toyooka S, Virmani AK, Toyooka KO, Seidl S, Minna JD, Gazdar AF. Aberrant methylation of multiple genes in the upper aerodigestive tract epithelium of heavy smokers. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:612–616. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong TS, Man MWL, Lam AKY, Wei WI, Kwong YL, Yuen APW. The study of p16 and p15 gene methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their quantitative evaluation in plasma by real-time PCR. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1881–1887. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira MA, Tao L, Wang W, Li Y, Umar A, Steele VE, Lubet RA. Modulation by celecoxib and difluoromethylornithine of the methylation of DNA and the estrogen receptor-alpha gene in rat colon tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1917–1923. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toyooka S, Maruyama R, Toyooka KO, McLerran D, Feng Z, Fukuyama Y, Virmani AK, Zochbauer-Muller S, Tsukuda K, Sugio K, Shimizu N, Shimizu K, Lee H, Chen CY, Fong KM, Gilcrease M, Roth JA, Minna JD, Gazdar AF. Smoke exposure, histologic type and geography-related differences in the methylation profiles of non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:153–160. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WCRF/AICR: 4.8 Alcoholic drinks. Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. AICR; Washington DC: 2007. pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2765–2778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botteri E, Iodice S, Raimondi S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Cigarette smoking and adenomatous polyps: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:388–395. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IARC: IARC handbooks of cancer prevention. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Vol. 1. IARC; Lyon: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson J, Whitney DH, Durkee K, Shuber AP. DNA stabilization is critical for maximizing performance of fecal DNA-based colorectal cancer tests. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2005;14:183–191. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176768.18423.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou H, Harrington JJ, Klatt KK, Ahlquist DA. A sensitive method to quantify human long DNA in stool: relevance to colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1115–1119. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itzkowitz S, Brand R, Jandorf L, Durkee K, Millholland J, Rabeneck L, Schroy PC, 3, Sontag S, Johnson D, Markowitz S, Paszat L, Berger BM. A simplified, noninvasive stool DNA test for colorectal cancer detection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2862–2770. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Issa JP, Ahuja N, Toyota M, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. Accelerated age-related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3573–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakami K, Ruszkiewicz A, Bennett G, Moore J, Grieu F, Watanabe G, Iacopetta B. DNA hypermethylation in the normal colonic mucosa of patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:593–598. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khazaie K, Schirrmacher V, Lichtner RB. EGF receptor in neoplasia and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1993;12:255–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00665957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malecka-Panas E, Kordek R, Biernat W, Tureaud J, Liberski PP, Majumdar APN. Differential activation of total and EGF receptor tyrosine kinase in the rectal mucosa in patients with adenomatous polyps, ulcerative colitis and colon cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:435–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandt B, Hermann S, Straif K, Tidow N, Buerger H, Chang-Claude J. J Modification of breast cancer risk in young women by a polymorphic sequence in the egfr gene. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller VA, Kris MG, Shah N, Patel J, Azzoli C, Gomez J, Krug LM, Pao W, Rizvi N, Pizzo B, Tyson L, Venkatraman E, Ben-Porat L, Memoli N, Zakowski M, Rusch V, Heelan RT. Bron-chioloalveolar pathologic subtype and smoking history predict sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1103–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Zhu CQ, Kamel-Reid S, Squire J, Lorimer I, Zhang T, Liu N, Daneshmand M, Marrano P, da Cunha Santos G, Lagarde A, Richardson F, Seymour L, Whitehead M, Ding K, Pater J, Shepherd FA. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1331–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E, Bartolini S, Ceresoli GL, Bemis L, Haney J, Witta S, Danenberg K, Domenichini I, Ludovini V, Magrini E, Gregorc V, Doglioni C, Sidoni A, Tonato M, Franklin WA, Crino L, Bunn PA, Jr, Varella-Garcia M. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang XT, Li LY, Mu XL, Cui QC, Chang XY, Song W, Wang SL, Wang MZ, Zhong W, Zhang L. The EGFR mutation and its correlation with response of gefitinib in previously treated Chinese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1334–1342. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark GM, Zborowski DM, Santabarbara P, Ding K, Whitehead M, Seymour L, Shepherd FA. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group: Smoking history and epidermal growth factor receptor expression as predictors of survival benefit from erlotinib for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer in the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study BR.21. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:389–394. doi: 10.3816/clc.2006.n.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Z, Bepler G, Cantor A, Haura EB. Small tumor size and limited smoking history predicts activated epidermal growth factor receptor in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:308–316. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugio K, Uramoto H, Ono K, Oyama T, Hanagiri T, Sugaya M, Ichiki Y, So T, Nakata S, Morita M, Yasumoto K. Mutations within the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR gene specifically occur in lung adenocarcinoma patients with a low exposure of tobacco smoking. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:896–903. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bae NC, Chae MH, Lee MH, Kim KM, Lee EB, Kim CH, Park TI, Han SB, Jheon S, Jung TH, Park JY. EGFR, ERBB2, and KRAS mutations in Korean non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;173:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mounawar M, Mukeria A, Le Calvez F, Hung RJ, Renard H, Cortot A, Bollart C, Zaridze D, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Brambila E, Hainaut P. Patterns of EGFR, HER2, TP53, and KRAS mutations of p14arf expression in non-small cell lung cancers in relation to smoking history. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5667–5672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Na II, Rho JK, Choi YJ, Kim CH, Park JH, Koh JS, Ryoo BY, Yang SH, Lee JC. The survival outcomes of patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer differ according to EGFR mutations and the P21 expression. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sasaki H, Kawano O, Endo K, Yukiue H, Yano M, Fujii Y. EGFRvIII mutation in lung cancer correlates with increased EGFR copy number. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, Singh B, Heelan R, Rusch V, Fulton L, Mardis E, Kupfer D, Wilson R, Kris M, Varmus H. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon YK, Sung SW, Chung JH, Park WS, Seo JW, Kim CW, Chung DH. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic implications of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene copy number and protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moroni M, Veronese S, Benvenuti S, Marrapese G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Gambacorta M, Siena S, Bardeli A. Gene copy number for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and clinical response to antiEGFR treatment in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:279–286. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seitz HK, Simanowski UA. Cell turnover in the gastroin-testinal tract and the effect of ethanol. In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, editors. Alcohol and the gastrointestinal tract. CRC Press; Boca Rato, FL: 1996. pp. 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simanowski UA, Homann N, Knühl M, Arce L, Waldherr R, Conradt C, Bosch FX, Seitz HK. Increased rectal cell proliferation following alcohol abuse. Gut. 2001;49:418–422. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincon P, Wunderer J, Simanowski UA, Koll M, Preedy VR, Peters TJ, Werner J, Waldherr R, Seitz HK. Inhibition of alcohol-associated colonic hyperregeneration by alpha-to-copherol in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:100–106. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046341.31828.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amin PB, Diebel LN, Liberati DM. The intestinal epithelial cell modulates the effect of alcohol on neutrophil inflammatory potential. J Trauma. 2007;63:1223–1229. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815b83fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleming S, Toratani S, Shea-Donohue T, Kashiwabara Y, Vogel SN, Metcalf ES. Pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression in the murine small intestine and liver after chronic exposure to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:579–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shames DS, Minna JD, Gazdar AF. Methods for detecting DNA methylation in tumors: from bench to bedside. Cancer Lett. 2007;251:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho SM, Tang WY. Techniques used in studies of epigenome dysregulation due to aberrant DNA methylation: an emphasis on fetal- based adult diseases. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:267–282. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coudry RA, Meireles SI, Stoyanova R, Cooper HS, Carpino A, Wang X, Engstrom PF, Clapper ML. Successful application of microarray technology to microdissected formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:70–79. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soegaard M, Jensen A, Frederiksen K, Høgdall E, Høgdall C, Blaakaer J, Kjaer SK. Accuracy of self-reported family history of cancer in a large case-control study of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:469–479. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Young GP, Sano Y, Chiu HM, Byeon SJ, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Solano J, Rerknimitr R, Matsuda T, Wu KC, Ng S, Leung SY, Makharia G, Chong VH, Ho KY, Brooks D, Lieberman DA, Chan FK. Asia Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer: Asia Pacific consensus recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2008;57:1166–1176. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.146316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]