Significance

An important development in social psychology is the discovery of minor interventions that have large behavioral effects. A leading example is a recent PNAS paper showing that a modest intervention inspired by psychological theory—wording survey items to encourage subjects to think of themselves as voters (noun treatment) rather than as voting (verb treatment)—has a large positive effect on political participation (voter turnout). We replicate and extend these experiments. In a large-scale field experiment, we find that encouraging subjects to think of themselves as voters rather than as voting has no effect on turnout and we estimate that both are less effective than a standard get out the vote mobilization message.

Keywords: psychology, political science, intervention, field experiment, voter turnout

Abstract

One of the most important recent developments in social psychology is the discovery of minor interventions that have large and enduring effects on behavior. A leading example of this class of results is in the work by Bryan et al. [Bryan CJ, Walton GM, Rogers T, Dweck CS (2011) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(31):12653–12656], which shows that administering a set of survey items worded so that subjects think of themselves as voters (noun treatment) rather than as voting (verb treatment) substantially increases political participation (voter turnout) among subjects. We revisit these experiments by replicating and extending their research design in a large-scale field experiment. In contrast to the 11 to 14% point greater turnout among those exposed to the noun rather than the verb treatment reported in the work by Bryan et al., we find no statistically significant difference in turnout between the noun and verb treatments (the point estimate of the difference is approximately zero). Furthermore, when we benchmark these treatments against a standard get out the vote message, we estimate that both are less effective at increasing turnout than a much shorter basic mobilization message. In our conclusion, we detail how our study differs from the work by Bryan et al. and discuss how our results might be interpreted.

Recent work in social psychology has shown that very modest alterations in how a decision is described or structured can have outsized effects on the choices that people make. The discovery of brief interventions that dramatically alter behavior has been called “one of the most exciting developments in psychological science in recent years,” and the spectacular behavioral responses that follow minor interventions are described by one proponent as so remarkable that they sound more like “science fiction than science.” Indeed, much of what is now accepted science in fields outside of psychology, from mold that cures deadly infections to power plants that transform a few tons of uranium into the energy to light a city, would once have seemed like science fiction. Walton (1) has labeled these new approaches “wise interventions,” with the double meaning that they are both brilliantly effective and also savvy to the subtle truths of our psychology.

A prominent example of this new approach, in which a brief intervention is crafted based on a psychological theory, is a study showing how a minor difference in survey wording leads to large differences in the respondents’ voting in elections (i.e., their turnout behavior). [This study is one of three featured in the recent article by Walton (1) promoting “wise interventions.”] In a PNAS article, Bryan et al. (2) show that subtle linguistic differences in how the act of voting is framed can have large effects on participation. Bryan et al. (2) ground their theoretical argument in prior work showing that a behavior described using noun wording is perceived as a more stable and permanent attribute than a behavior described using a verb (3, 4). This distinction extends to self-perceptions; when a person describes an attribute as a central aspect of her identity using a noun (e.g., “I am a basketball fan”), she evaluates that characteristic as stronger, more stable, and more resilient than when she describes it using a descriptive action verb (e.g., “I watch basketball a lot”) (4). Drawing on this work, Bryan et al. (2) argue that priming individuals to think of themselves as voters (noun) rather than as individuals who vote (verb) raises the identity stakes associated with the decision to participate, thereby leading the noun treatment to produce a greater likelihood to vote than the verb treatment.

In three experiments with modest sample sizes, Bryan et al. (2) examined whether subjects who completed a 10-item survey about voting that described voting using noun wordings (e.g., “How important is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming election?”) rather than using verbs (e.g., “How important is it to you to vote in the upcoming election?”) were more likely to participate in politics. Because the noun wording “offers the possibility of claiming or reclaiming a personal attribute by engaging in that behavior” (ref. 2, p. 12653), those described as voters were expected to be more likely to turn out to vote.

Experiment 1 was a survey experiment, in which 34 subjects recruited from a university-administered online participant pool were randomly assigned to either the noun or verb version of a survey about the upcoming 2008 election. Those assigned to the noun condition were subsequently more likely to express an interest in registering to vote for the election (4.4 vs. 3.4 on a 5-point scale measured from “not at all interested” to “extremely interested”). Experiments 2 and 3 were conducted in the field and combined surveys administered online with turnout measured using state voter file records. In experiment 2, among 88 subjects successfully matched to a California voter file and not excluded for other reasons, those assigned to a noun rather than a verb form of a set of survey items similar to that used in experiment 1 were 14% points (95.5% vs. 81.8%) more likely to vote in the 2008 presidential election. In experiment 3, among 214 subjects successfully matched to a New Jersey voter file, those in the noun condition were 11% points (89.9% vs. 79.0%) more likely to vote in the 2009 gubernatorial election, a finding that is particularly interesting because only 47% of registered voters (registrants) voted in this race compared with 79% of registrants who voted in the 2008 presidential election in California.

The substantial increase in voting rates that Bryan et al. (2) generate through very subtle wording changes is noteworthy and somewhat surprising. In their two field experiments, for example, simply altering how an individual is described (as a voter vs. engaged in the act of voting) increases turnout by about 14% and 11% points, respectively. Although the authors do not directly assess the theoretical claim that the use of noun rather than verb language raised the identity stakes of voting in the subject’s subsequent decision to vote, the direction of the observed behavioral response is consistent with their proposed theoretical mechanism (2).

Compared to the numerous prior voter mobilization field experiments, which often involve several thousand or more subjects, the magnitude of these treatment effects is quite large. Although the mode of treatment administration (the internet) is different from that used in most other mobilization studies (e.g., direct mail or phone calls), prior work nearly always finds much smaller treatment effects. For example, a meta-analysis by Green and Gerber (5) of previous studies looking at the effect of direct mailing on turnout estimates the impact of a single piece of nonpartisan, nonadvocacy mail to be roughly 0.5% points or about 22 times smaller than the 11% point effect found in experiment 3 in the work by Bryan et al. (2). Even mail that invokes strong social pressure to partake in the socially desirable act of voting, which is frequently the most effective message, on average, raises turnout by only 2.3 points. Treatments administered by telephone are sometimes more effective than mailings, but compared with an uncontacted control group, the most effective calls (live calls made by volunteers), on average, increase turnout by only 2.9 points. Furthermore, the general finding in the literature is that mobilization effects are largest in less salient elections (during which baseline mobilization efforts are low and turnout is modest) and much less effective in the highest profile races [as in the presidential election context for experiments 1 and 2 in the work by Bryan et al. (2)] (6). [One reason it is hypothesized that it is harder to increase turnout in more salient races is that many more individuals are already “treated” by campaigns, the media, and the larger (social) campaign environment in ways that induce individuals to vote through many different psychological mechanisms.]

The intervention by Bryan et al. (2) increases turnout without providing strong political reasons for voting. However, this emphasis on encouraging participation by producing positive psychological associations with the act of voting rather than by encouraging voting for instrumental reasons is a common and sometimes effective approach. The personal instrumental benefits from voting are likely smaller than the costs of doing so, because the odds that a voter affects the outcome of a mass election (i.e., is “pivotal”) is approximately zero (7). In light of this argument, researchers have studied a number of alternative motivations for political participation. Experimental interventions shown to increase turnout include efforts to apply (as mentioned above) social pressure (8) as well as more subtle efforts to reinforce prosocial behavior by expressing gratitude for previous participation (9). However, although the election reminder in both the “noun” and “verb” treatment scripts may be expected to produce some voting increase, even the most effective messages used in previous trials seem much less effective than the novel “noun treatment” studied by Bryan et al. (2).

Given the significance of the research by Bryan et al. (2) as both a leading example of an important class of interventions and a specific means to encourage political participation, we conducted a large-scale field experimental study of these interventions to understand their absolute and relative effectiveness. In addition to comparing the relative efficacy of the noun and verb survey instruments, we also benchmark the effectiveness of these interventions to simply making contact (a nonpolitical placebo survey) and a standard get out the vote (GOTV) message that provides information about the upcoming election and mentions that many other people are expected to vote (a social norms message).

We make two central contributions. First, we show that the results reported in the work by Bryan et al. (2) may not generalize beyond the contexts present in the original experiments. [Because we use the treatment scripts tested in the work by Bryan et al. (2), our work can be considered a replication. However, given that some elements are different, alternatively, our study may instead quite reasonably be thought of as a test of robustness showing a failure to generalize rather than as a failure to replicate. Although our study uses the same 10-item treatment battery as that in the work by Bryan et al. (2), our experiments took place in a different political context (primary elections rather than presidential or gubernatorial general elections) and used live telephone callers rather than the internet to deliver the treatment scripts.] To be clear, that our findings differ does not suggest that there was anything wrong with the design or analysis in the pioneering study by Bryan et al. (2). Rather, we follow the suggestion of Bryan et al. (2), who note that it would be useful to understand “whether this [mobilization] effect would remain as strong if delivered at the population level” and that “many behaviors that policy-makers seek to encourage are similarly private…” (ref. 2, p. 12655). Our experiment, which is conducted on a much larger scale among a randomly selected set of all registrants and in several states with varying levels of electoral competitiveness, provides little evidence that the noun treatment is effective in increasing the frequency of voting over the verb treatment.

Second, our experiment, which appears to be the first independent attempt, to our knowledge, to test the method proposed by Bryan et al. (2), raises the possibility that the result reported in the work by Bryan et al. (2) may have been a false positive, perhaps induced by sampling variability. Our result implies that, even if the same experimental procedures used in the original study were repeated (a hypothetical proposal given that a prior electoral context cannot be perfectly reproduced), the original result might not hold. Follow-up studies that examine reproducibility and robustness are an important step in consolidating our understanding of a novel approach given the frequency with which initially promising findings are not found in subsequent studies, despite large effect sizes and small P values (10, 11). Overall, our results provide information that the larger scholarly and policy community should take into account when evaluating the accuracy and importance of the claim that these types of very minor interventions can be used to motivate significant behavioral changes, particularly because the noun treatment seems less effective than a standard voter mobilization message.

Study Details

Our field experiment was conducted during the 2014 primary elections in three states (Michigan, Missouri, and Tennessee) in which all registered citizens can vote in any party’s primary election. We first obtained a complete list of registered voters in each state. Before treatment assignment, we excluded records likely to be invalid or persons who could not be contacted by phone. In households with multiple registrants, one registrant was selected at random for inclusion in the sample. From this pool, subjects were then randomly assigned to a treatment, four of which we analyze here: the noun-based 10-item treatment script [the same script used in the work by Bryan et al. (2)], a parallel verb version of that treatment script [the same script used in the work by Bryan et al. (2)], a nonpolitical “placebo” intervention, and a standard GOTV message. [Complete phone scripts are provided in Supporting Information along with the scripts used by Bryan et al. (2) for comparison. Non-English speakers were excluded as noncontacted.] Treatment assignment was stratified by state, whether the registrant lived in a district with a competitive House race, and past record of voter participation. (Assignment stratum details are reported in Supporting Information. Registrants were assigned to the placebo message at twice the rate of the other interventions.)

Each message was delivered by telephone in the 4 days leading up to each state’s primary election by a professional survey vendor that we hired for the experiment. We remotely monitored a subset of the vendor’s calls to confirm that callers were following the scripts as written. After confirming contact with the selected person, all four interventions began with the same question asking whether the subject was a resident of his/her state. Subjects who were reached by telephone and answered in the affirmative are coded as contacted. When we present our statistical findings, we compare outcomes across treatments among subjects who we successfully contacted by phone using this common (treatment-independent) definition of contact (subjects are coded as contacted if and only if they answered yes when asked if they were a resident of their state). It is important to note that this question was asked before the portion of each script that branches into the respective treatment. Voting in the 2014 primary was measured using turnout as recorded in updated state voter files obtained from a vendor in March of 2015 and linked using the original voter file identification number. Individuals are coded as having voted if they are recorded as having done so in the official record, and they are coded as not having voted if they either are recorded as not having done so in the official record or no longer appear in the voter file.

Our vendor contacted 2,236 registrants in the “voter” (noun) condition, 2,232 in the “voting” (verb) condition, 4,402 in the placebo condition, and 2,229 in the GOTV condition. Note that the over 4,400 subjects assigned to the noun and verb conditions are many times the sample size of the two field experiments (experiments 2 and 3) reported in the work by Bryan et al. (2), and therefore, this study is less sensitive to sampling variability. Additionally, it is adequately powered to detect even small differences in treatment effectiveness. [Specifically, assuming a Type I error rate of 0.05, a Type II error rate of 0.2, and baseline turnout of about 29% (the observed rate among the subjects in the placebo condition), the study is sufficiently powered to detect about a 3% point increase in turnout over the placebo condition.]

Table S1 shows that treatment groups did not vary to a material degree for available covariates (age, year of registration, sex, race/ethnicity, and the number of times having voted in previous general, primary, and special elections). [A chi-squared test from a multinomial logit model for all covariates predicting assignment to treatment group is not significant (P = 0.82).]

Results

Effectiveness of Noun Vs. Verb Intervention.

We examine the behavioral response associated with the treatment by conducting differences in proportions tests for turnout between those in the voter and voting conditions. [For an overall additive scale as well as for 7 of 10 individual items in the treatment scripts, we find that the noun treatment induced more positive assessments (P < 0.05) of participation than that verb treatment. This pattern suggests that the treatments were successfully deployed and understood as different messages by recipients. Complete results are in Table S2.] In contrast to the findings by Bryan et al. (2), column 4 in Table 1 shows that participation rates in the two groups are statistically indistinguishable. Overall participation was 1.0 point lower for those in the noun condition than for those in the verb condition (30.1% vs. 31.1%; n = 4,468; P = 0.45). The 95% confidence interval for this estimate (−1.8 to 3.8 points) implies that the data are broadly consistent with effects from noun vs. verb in the +2% to −4% point range. The largest effect in the 95% confidence interval, 2% points, is far smaller than the lesser of the two estimates reported in the work by Bryan et al. (2).

Table 1.

Effect of voter and voting treatments on 2014 primary election turnout

| Sample | Proportion voting, voter treatment | Proportion voting, voting treatment | Difference of proportions (voter − voting) [SE] | Regression estimate of difference (voter − voting) [SE] | No. of observations (voter; voting) |

| Entire sample | 0.301 | 0.311 | −0.010 [0.014] | −0.004 [0.011] | 2,236; 2,232 |

| State: Michigan | 0.234 | 0.242 | −0.008 [0.019] | −0.007 [0.015] | 1,041; 1,015 |

| State: Missouri | 0.333 | 0.341 | −0.008 [0.028] | −0.005 [0.023] | 577; 563 |

| State: Tennessee | 0.383 | 0.393 | −0.009 [0.027] | 0.000 [0.021] | 618; 654 |

| No competitive house primary | 0.321 | 0.339 | −0.018 [0.018] | −0.011 [0.015] | 1,307; 1,305 |

| Either house primary competitive | 0.273 | 0.273 | 0.000 [0.021] | 0.004 [0.016] | 929; 927 |

| Ever voters | 0.326 | 0.338 | −0.013 [0.015] | −0.004 [0.012] | 2,047; 2,033 |

| Have voted in primary | 0.596 | 0.632 | −0.037 [0.024] | −0.014 [0.021] | 848; 832 |

| Have voted but never in primary | 0.135 | 0.135 | 0.000 [0.014] | 0.003 [0.013] | 1,199; 1,201 |

| No prior history of voting | 0.032 | 0.035 | −0.003 [0.018] | −0.003 [0.018] | 189; 199 |

| Predicted turnout >70% | 0.764 | 0.781 | −0.017 [0.030] | −0.007 [0.027] | 377; 407 |

The estimates in column 5 were generated from regression models including strata (strata × vote history × district competitiveness) fixed effects and state interacted with indicators for age, year of registration, sex, race/ethnicity, and the number of times voted in general, primary, and special elections (complete model results are reported in Table S3). No differences in proportions or regression estimates are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Also, we did not find evidence that the noun intervention is more effective when we partition the data by state, district electoral context, past patterns of voter participation, or expected turnout rates. Turnout was higher in the verb condition by 0.8 points in Michigan (24.2% vs. 23.4%; n = 2,056; P = 0.67), 0.8 points in Missouri (34.1% vs. 33.3%; n = 1,140; P = 0.77), and 1.0 point in Tennessee (39.3% vs. 38.3%; n = 1,272; P = 0.73). In noncompetitive primary districts, turnout was 1.8 points higher for those in the verb condition (33.9% vs. 32.1%; n = 2,612; P = 0.32), whereas in competitive primary districts, participation was nearly identical in both conditions (27.3%; n = 1,856; P = 0.98). Across groupings of past participation behavior, the verb treatment is more effective than the noun treatment for those who have ever voted (33.8% vs. 32.6%; n = 4,080; P = 0.39), ever voted in a primary (63.2% vs. 59.6%; n = 1,680; P = 0.13), and with no record of prior voting (3.5% vs. 3.2%; n = 388; P = 0.85). For registrants who had previously voted but never participated in a primary, turnout is 13.5% in both treatment groups (n = 2,400; P = 0.98). Finally, among registrants with a predicted baseline probability of voting greater than 70%, turnout is lower in the noun than in the verb condition. (Expected turnout is constructed based on the relationship between voting, demographics, and electoral context using the relationship observed among those in the voting condition. More details are in Supporting Information.)

The estimates reported in column 5 in Table 1 show that we obtain similar null results when we analyze our data using ordinary least squares regression, an approach that allows us to account for observable covariates and the stratified nature of our sampling method and treatment assignment. [Data are weighted by propensity to be assigned to treatment based on vote history, state, and district competitiveness. We also include indicators (fixed effects) for each assignment strata (state × district competitiveness × vote history).] The dependent variable is whether the individual voted in the 2014 primary (1, yes; 0, no), which we model as a function of assignment to the noun treatment (those receiving the verb treatment serve as the baseline category). Positive coefficient estimates indicate that turnout is higher in the noun than in the verb condition. We include as covariates indicators for the list of demographic, political, and participatory factors taken from the voter file and used in the balance tests. Each of these variables is interacted with a state indicator to capture variation in their effects across states. Full model results are in Table S3.

For the entire sample and 10 subsamples analyzed in Table 1, 9 of the estimates for noun minus verb treatment effect are negative or zero, implying the best guess of the effect of the noun rather than verb treatment is that it either reduces participation or leads to no difference in relative effects. For example, for the entire sample, the point estimate is −0.4% points, with a 95% confidence interval of about −2.6 to 1.8 points, which again excludes the smallest treatment estimate reported in the work by Bryan et al. (2). In two subsamples (places where either party primary was competitive or among voters who have never participated in a primary), we estimate positive effects, but they are substantively small and far from statistically significant.

Robustness.

The analyses in Table 1 include all individuals who confirmed their state of residence (i.e., answered the first question asked in both treatments). We could, however, adopt a stricter definition of treatment in light of the fact that some respondents break off contact (there is attrition) from this point to the end of the 10-question treatment script. For example, we might consider an individual treated if she, instead, provides a response to the second question asked in both treatments about awareness of the upcoming primary. Alternatively, we might restrict our attention to only those individuals who complete all 10 survey items (although because these items differ in the two treatment arms, this subsample may also be different across treatments, creating a possibility of selection bias). Panel A in Table S4 replicates the analysis in Table 1 for those who answered the election awareness item and confirms the pattern of finding little evidence that the noun treatment increases turnout (full model results for all analyses reported in Table S4 are in Tables S5–S7). Focusing on the regression estimates, the largest effect is −0.4 points. Similarly, when we restrict attention in panel B in Table S4 to those who completed the entire 10-item treatment script, the largest estimated regression coefficient is 1 point (with a SE of 3.3 points).

We also consider one potential source of the difference between our results and those reported in the work by Bryan et al. (2) that might follow from a difference in our experimental design. In their two field experiments, individuals were contacted the day before or the morning of the election, whereas our calls took place during the 4 days before each election. For this reason, in panel C in Table S4, we restrict our attention to the nonrandom subset of those individuals who completed the entire survey and were contacted the day before the election. (We did not call respondents on Election Day; in Tennessee, no calls were made the day before the election for budgetary reasons.) Focusing again on the regression estimates, for this entire subsample (n = 885), the point estimate is 0.2 points (SE = 2.5 points; not statistically significant). The largest estimate is 6.5 points (SE = 8.8 points; not statistically significant) for the subsample of respondents whose predicted baseline turnout rate was greater than 70% (n = 110). [For this subsample, we find that both the noun and verb treatments are less effective in inducing voting (have negative point estimates) compared with the nonpolitical placebo message discussed below.] Thus, even when we restrict attention to those who both completed the entire survey and did so just before the election, we continue to find no evidence that the noun intervention is more effective than the verb intervention in increasing participation.

Comparative Message Effectiveness.

The preceding analysis provides little evidence that completing a survey using a noun to describe the act of voting increases participation more than when a verb is used. Despite the absence of a difference between the two treatment groups, however, both the noun and verb treatment scripts might still positively affect participation and thus, serve as valuable mobilization tools. Alternatively, the political environment might have been such that no mobilization script was effective. To test these possibilities, we use the two additional treatments included in our experiment: a placebo condition and a standard GOTV message. Examining the effect of the latter message also allows us to understand whether, for this particular sample, electoral environment, and experimental protocol, a commonly used message can be effective in mobilizing voters.

Across the four treatments, the interviewer asked for the selected registrant by name, and as previously explained, our analysis is restricted to those subjects who confirmed that they were still residents of the state as determined from the official record. After this point, the treatments diverged. Subjects in the placebo condition received no political message but were, instead, asked how many times in the past 14 days that they had visited the grocery store. This treatment condition allows us to create a suitable comparison group of individuals—those who we can reach on the phone—for those who receive any message with political content. In the GOTV condition, subjects were asked a single question: “This [DAY], [STATE] will be holding primary elections to select which candidates will be on the ballot this November. Many [STATE] citizens are expected to turn out for this [DAY]’s election. Were you aware that [STATE]’s primary elections will be held this [DAY]?” The GOTV treatment, therefore, differed from the noun and verb conditions in two ways. First, it ended after this item and did not include a 10-item survey. Second, it mentioned that many citizens were expected to vote, a message that may make salient a norm of participation.

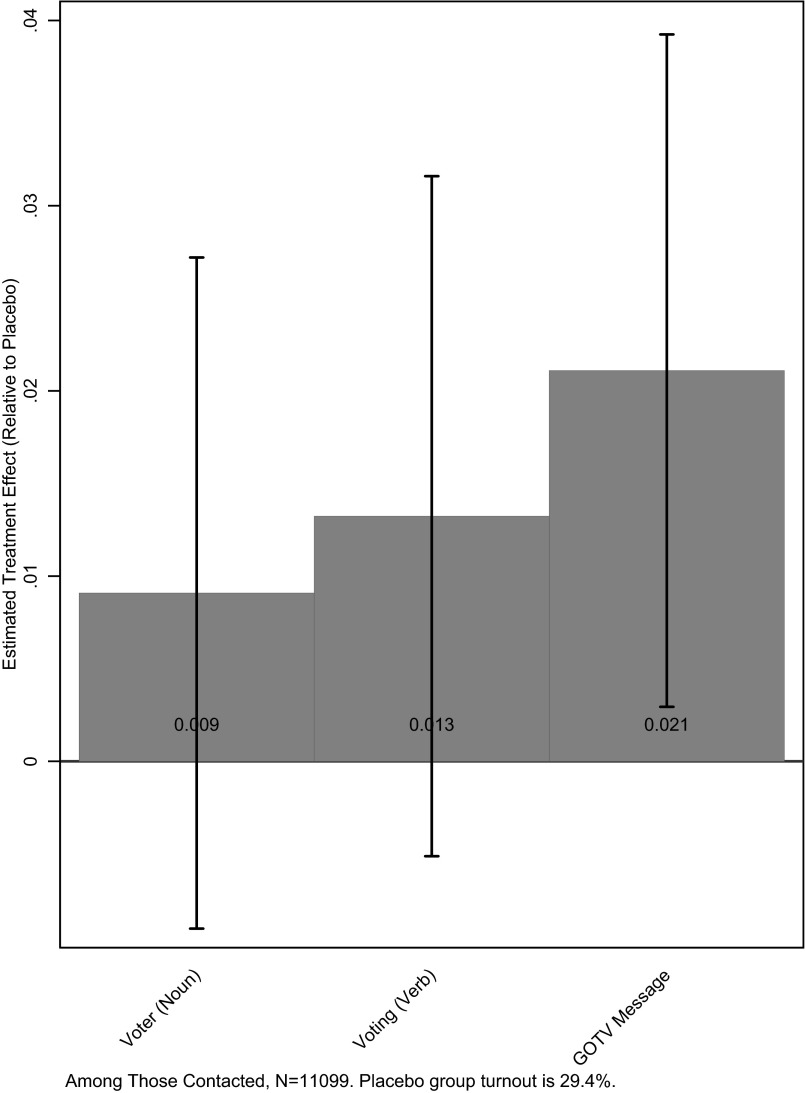

Fig. 1 displays the comparative effectiveness of each treatment in increasing participation relative to the placebo message (the 95% confidence interval for each estimate is indicated with the black capped lines). These estimates are derived from a regression model similar to that used in the analysis in Table 1 (full results are in Table S8). Compared with the placebo condition, those who received the voter (noun) intervention are 0.9 points more likely to vote, although the estimated difference between this treatment and the grocery (placebo) treatment is not statistically significant. Similarly, those who received the voting (verb) intervention are 1.3 points more likely to vote, although this estimate is also not statistically significant. As in Table 1, these treatment effects are indistinguishable from one another.

Fig. 1.

Comparative effectiveness of different treatments: point estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

Combining the noun and verb treatments, the average estimated effect relative to the placebo message is 1.1 points (P = 0.14). Although this 1.1% point effect is not large, it is similar to what prior research has found for other phone messages in other contexts, indicating that neither the noun nor the verb message has an outsized effect on participation. Furthermore, neither message is as effective as the (much shorter) standard GOTV message that provides the same information about the upcoming election and mentions that many voters will participate. As the third bar in Fig. 1 shows, that message increases turnout by a statistically significant 2.1% points (P < 0.05). When we compare the effect of the standard GOTV message with the pooled estimate of the noun and verb treatments, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the treatments are equally effective (P = 0.29 from a test of a linear combination of coefficients), but the point estimate for the standard GOTV intervention is 1 point larger. Additionally, given that both the noun and verb treatments are much longer (and therefore, more costly to administer), these findings suggest that those interested in mobilization are best served by using the shorter script.

Discussion

One of the most exciting areas of research in psychology is the discovery of brief psychological interventions that can cause substantial behavioral change. In this paper, we investigated the robustness of one of the most striking examples of this new class of interventions. Bryan et al. (2) found that subtle wording differences in question wording, specifically the use of a noun (voter) rather than a verb (voting) to describe an action, can generate significantly higher turnout rates when applied to the act of voting. This finding buttresses the general claim regarding the potential for large behavioral effects from minimal interventions, a claim with implications for both public policy and our understanding of choice. It also identifies an important new means for increasing political participation.

Building on the field experiments by Bryan et al. (2), we implemented their treatment language using a significantly larger sample in the context of the 2014 House primary elections. In contrast to the prior study, we find little evidence that priming individuals to think of themselves as voters produces higher participation rates than when describing them as engaged in the act of voting. Furthermore, these treatment calls increase turnout only modestly compared with a placebo call and seem less effective than a much shorter standard GOTV script.

Our failure to find the same differences in turnout identified by Bryan et al. (2) may stem from a number of factors. Specifically, there are several differences in the implementation of the two studies, such that our study is not an exact replication of the experimental conditions in the work by Bryan et al. (2). First, we examine an electoral context (a primary election) that differs from that used by Bryan et al. (2) (a presidential election and a gubernatorial election). Speculating in a posthoc fashion, perhaps the effect of noun vs. verb wording occurs only in high- or medium-profile elections, because the perceived loss of identity associated with failing to vote is weaker and less susceptible to priming in primary contests, where turnout is generally lower (turnout rates among registrants in our experimental settings were 28% in Tennessee, 25% in Missouri, and 21% in Michigan). However, as we note above, prior experimental work suggests that mobilization is typically more, not less, effective in modest turnout rather than the most salient elections (6), a pattern that holds for psychologically inspired mobilization messages, such as those that invoke social pressure in an effort to increase participation. Furthermore, if lower election intensity reduces treatment effectiveness, we would expect that Bryan et al. (2) would have found larger incremental turnout effects from the noun message in a presidential race (experiment 2; state turnout rate among registrants = 79.4%) than in a gubernatorial contest (experiment 3; state turnout rate among registrants = 47%), but their treatment effect estimates are similarly large in these two contexts.

Second, whereas Bryan et al. (2) relied on treatments administered through the internet that required subjects to read the 10 items and manually record their answers, our treatments were administered over the phone. Although it does not seem intuitive, perhaps subject attention is greater or the differentiation between noun and verb use is clearer to subjects when they read questions on a computer screen and manually select answers rather than listen to treatment items and answer questions orally.

Two other possibilities for our null finding relate to differences in the samples used. Because our sample (drawn from voter files in three states) was likely more representative than that used by Bryan et al. (2), their findings (or our findings) may be population-specific (convenience samples drawn from colleges campuses used in the first two studies) or state-specific (the third experiment was limited to New Jersey, and subjects had a much higher rate of turnout than the average registered voter in the New Jersey election studied). A second distinction is our reliance on a sample taken from existing voter rolls, which ensures that all participants were registered voters and makes it easier to accurately identify whether they voted. [In contrast, Bryan et al. (2) rely on self-reported registration and exclude from their analysis those who they cannot manually match to voter records postelection.]

Finally, our failure to find similar treatment effects may be caused by simple random chance. Although we cannot rule out this possibility, our experiment was designed with sufficient statistical power to detect substantially smaller treatment effects than those reported in the prior research.

Assuming chance does not account for our results, one interpretation of our failure to reproduce the findings in the work by Bryan et al. (2) is that the treatment effects previously reported are accurate but highly sensitive to electoral context, mode of communication, or subject characteristics. Learning that modest differences in design eliminate the effectiveness of a psychological intervention helps to guide our understanding of the limitations of its potential general significance as a tool for promoting the broad class of prosocial behaviors that Bryan et al. (2) suggest are analogous to voting. Given the differences between our results and the findings in Bryan et al. (2), it would be useful to prespecify, and then test, the specific circumstances under which theory would predict large differences in participation from the noun vs. verb experimental variation rather than our finding of no difference.

Methods

The goal of our research was to measure the effect of voter mobilization scripts on voter turnout in a natural setting. This research was approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Committee, which waived the requirement to obtain informed consent. The treatment materials used in the experiment informed subjects that participation was voluntary.

SI Description of Sampling Strategy

For this study, we first obtained voter files from a private vendor for Missouri, Tennessee, and Michigan. In all of these states, unaffiliated voters (i.e., voters not registered with a political party) can vote in any party’s primary elections without taking additional steps before arriving at the polls on Election Day. We then excluded records that, based on experience, are likely to be bad records or people who could not be reached by mail. Using the set of records that survived this screening, for each household with multiple registrants, we then randomly selected one voter from each household. We then selected a subset of these records (those with valid phone numbers for which the phone number was believed likely to be correct) for this experiment.

Every individual in the experimental samples was assigned to either control or a treatment group, but each individual in the samples did not have the same probability of being assigned to a treatment group. Assignment rates were based on two factors: individual vote history and political context. First, we constructed a dichotomous coding for whether an individual resided in a congressional district with a competitive or noncompetitive primary. Districts in our phone sample identified as having competitive partisan primaries are Michigan (Democratic: Districts 1, 8, 13, and 14; and Republican: Districts 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 11), Missouri (none), and Tennessee (Democratic: District 9; and Republican: District 4). Approximately 42% of our experimental subjects were selected from competitive districts, and about 58% were from noncompetitive districts.

Second, we tabulated the participation history of the voter. We partitioned the subjects into six groups based on their turnout histories as recorded in the voter file for the years 2008 to 2012. These six groups are listed.

-

i)

Primary voters (nonpresidential): voted in at least one nonpresidential primary in 2008, 2010, or 2012.

-

ii)

Primary voters (only presidential): voted in at least one presidential primary in 2008 or 2012 but did not vote in a nonpresidential primary in 2008, 2010, or 2012.

-

iii)

General election voters (nonpresidential): voted in at least one election between 2008 and 2012 other than the presidential general election in 2008 or 2012 and did not vote in any primary election in 2008, 2010, or 2012.

-

iv)

General election voters (only presidential): voted in a presidential election in 2008 or 2012 but did not vote in any other nonprimary election between 2008 and 2012 and did not vote in any primary election in 2008, 2010, or 2012.

-

v)

Never voters (new registrants): never voted but registered after November of 2012.

-

vi)

Never voters: never voted and registered before November of 2012.

We oversampled both types of general election voters (categories 3 and 4 above), thereby placing individuals who had previously voted but not in primary elections into treatment groups at a higher rate than the remainder of the sample. Furthermore, we undersampled primary voters (categories 1 and 2 above), thereby placing individuals who already showed a tendency to vote in primary elections into treatment groups at a lower rate than the remainder of the sample. Finally, we assigned never voters (categories 5 and 6 above) to treatment groups in proportion to their share in the overall sample. Specifically, for each of the states included in our phone experiment, we constructed state-level sampling weights, weighting each state’s population using the following formula:

Then, within strata defined by state, district competitiveness, and vote history categories, individuals included in the phone experiment reported in the text were randomly assigned to the noun or verb versions of the survey, a standard GOTV message, or a placebo survey. For statistical reasons, twice as many individuals were assigned to the placebo group than to the other experimental treatments. The regression analysis reported in the text accounts for this stratified sampling process.

SI Scripts Used in the Work by Bryan et al. (2)

Experiment 1.

-

i)

How important is it to you to (vote/be a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all important

Not too important

Neither important nor unimportant

Somewhat important

Extremely important

-

ii)

How much do you care about (voting/being a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither care nor don’t care

Somewhat

Very much

-

iii)

How much do you want to (vote/be a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither want nor don’t want

Somewhat

Very much

-

iv)

How personally relevant is it to you to (vote/be a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all relevant

Not too relevant

Neither relevant nor irrelevant

Somewhat relevant

Extremely relevant

-

v)

How difficult or easy do you think it is to (vote/be a voter) in the upcoming election?

Very difficult

Somewhat difficult

Neither difficult nor easy

Somewhat easy

Very easy

-

vi)

How convenient do you think it is to (vote/be a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all convenient

Not too convenient

Neither convenient nor inconvenient

Somewhat convenient

Extremely convenient

-

vii)

How consistent are your thoughts and feelings about (voting/being a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all consistent

Not too consistent

Neither consistent nor inconsistent

Somewhat consistent

Extremely consistent

-

viii)

How clear are your thoughts and feelings about (voting/being a voter) in the upcoming election?

Not at all clear

Not too clear

Neither clear nor unclear

Somewhat clear

Extremely clear

-

ix)

To what extent are your thoughts about (voting/being a voter) in the upcoming election the same as your feelings about (voting/being a voter)?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither the same nor not the same

Somewhat

Very much

-

x)

To what extent do your thoughts about (voting/being a voter) in the upcoming election differ from your feelings about (voting/being a voter)?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither differ not do not differ

Somewhat

Very much

Experiment 3.

The second experiment uses the same language except for minor word changes and always refers to “tomorrow’s” election.

-

i)

How important is it to you to (vote/be a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all important

Not too important

Neither important nor unimportant

Somewhat important

Extremely important

-

ii)

How much do you care about (voting/being a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither care nor don’t care

Somewhat

Very much

-

iii)

How much do you want to (vote/be a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither want nor don’t want

Somewhat

Very much

-

iv)

How personally relevant is it to you to (vote/be a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all relevant

Not too relevant

Neither relevant nor irrelevant

Somewhat relevant

Extremely relevant

-

v)

How easy do you think it is to (vote/be a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all easy

Not too easy

Neither difficult nor easy

Somewhat easy

Very easy

-

vi)

How convenient do you think it is to (vote/be a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all convenient

Not too convenient

Neither convenient nor inconvenient

Somewhat convenient

Extremely convenient

-

vii)

How consistent are your thoughts and feelings about (voting/being a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all consistent

Not too consistent

Neither consistent nor inconsistent

Somewhat consistent

Extremely consistent

-

viii)

How clear are your thoughts and feelings about (voting/being a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election?

Not at all clear

Not too clear

Neither clear nor unclear

Somewhat clear

Extremely clear

-

ix)

To what extent are your thoughts about (voting/being a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election the same as your feelings about (voting/being a voter)?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither the same nor not the same

Somewhat

Very much

-

x)

To what extent are your thoughts about (voting/being a voter) in (tomorrow’s/today’s) election different from your feelings about (voting/being a voter)?

Not at all

Not too much

Neither differ not do not differ

Somewhat

Very much

SI Telephone Treatment Scripts

VAR1: State.

VAR2: Day.

VAR3: Date.

Hi, could I speak to [name1] or [name2]? (Please enter identification number of target reached.)

Hi. My name is [interviewer’s first name], and I’m conducting a university research survey of registered voters. You can help us a lot by answering just a few questions. The survey is voluntary, and you don’t have to answer questions you don’t want to. I’m not selling anything, and the entire questionnaire will take fewer than 2 min to complete.

Are you currently a resident of [VAR1]?

01 Yes: Go to randomly assigned treatment

02 No: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

03 Other: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

04 Wouldn’t disclose: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

20 Declined conversation: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

21 Do not call: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

Voting (Verb) Treatment.

This [VAR2], [VAR1] will be holding primary elections to select which candidates will be on the ballot this November. Were you aware that [VAR1]’s primary elections will be held this [VAR2]?

1 Yes: Go to next question

2 No: Go to next question

96 Other: Go to next question

98 Refused: Go to next question

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How important is it to you to vote in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all important

2 Not too important

3 Neither important nor unimportant

4 Somewhat important

5 Extremely important

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How much do you care about voting in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all

2 Not too much

3 Neither care nor don’t care

4 Somewhat

5 Very much

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How much do you want to vote in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all

2 Not too much

3 Neither want nor don’t want

4 Somewhat

5 Very much

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How personally relevant is it to you to vote in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all relevant

2 Not too relevant

3 Neither relevant nor irrelevant

4 Somewhat relevant

5 Extremely relevant

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How difficult or easy do you think it is to vote in the upcoming primary election?

1 Very difficult

2 Somewhat difficult

3 Neither difficult nor easy

4 Somewhat easy

5 Very easy

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How convenient do you think it is to vote in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all convenient

2 Not too convenient

3 Neither convenient nor inconvenient

4 Somewhat convenient

5 Extremely convenient

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How consistent are your thoughts and feelings about voting in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all consistent

2 Not too consistent

3 Neither consistent nor inconsistent

4 Somewhat consistent

5 Extremely consistent

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How clear are your thoughts and feelings about voting in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all clear

2 Not too clear

3 Neither clear nor unclear

4 Somewhat clear

5 Extremely clear

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

To what extent are your thoughts about voting in the upcoming primary election the same as your feelings about voting?

1 Not at all

2 Not too much

3 Neither the same nor not the same

4 Somewhat

5 Very much

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

To what extent do your thoughts about voting in the upcoming primary election differ from your feelings about voting?

1 Not at all: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

2 Not too much: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

3 Neither differ nor not differ: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

4 Somewhat: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

5 Very much: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

96 Other: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

98 Refused: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

Voter (Noun) Treatment.

This [VAR2], [VAR1] will be holding primary elections to select which candidates will be on the ballot this November. Were you aware that [VAR1]’s primary elections will be held this [VAR2]?

1 Yes: Go to next question

2 No: Go to next question

96 Other: Go to next question

98 Refused: Go to next question

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How important is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all important

2 Not too important

3 Neither important nor unimportant

4 Somewhat important

5 Extremely important

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How much do you care about being a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all

2 Not too much

3 Neither care nor don’t care

4 Somewhat

5 Very much

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How much do you want to be a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all

2 Not too much

3 Neither want nor don’t want

4 Somewhat

5 Very much

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How personally relevant is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all relevant

2 Not too relevant

3 Neither relevant nor irrelevant

4 Somewhat relevant

5 Extremely relevant

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How difficult or easy do you think it is to be a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Very difficult

2 Somewhat difficult

3 Neither difficult nor easy

4 Somewhat easy

5 Very easy

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How convenient do you think it is to be a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all convenient

2 Not too convenient

3 Neither convenient nor inconvenient

4 Somewhat convenient

5 Extremely convenient

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How consistent are your thoughts and feelings about being a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all consistent

2 Not too consistent

3 Neither consistent nor inconsistent

4 Somewhat consistent

5 Extremely consistent

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

How clear are your thoughts and feelings about being a voter in the upcoming primary election?

1 Not at all clear

2 Not too clear

3 Neither clear nor unclear

4 Somewhat clear

5 Extremely clear

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

To what extent are your thoughts about being a voter in the upcoming primary election the same as your feelings about being a voter?

1 Not at all

2 Not too much

3 Neither the same nor not the same

4 Somewhat

5 Very much

96 Other

98 Refused

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

To what extent do your thoughts about being a voter in the upcoming primary election differ from your feelings about being a voter?

1 Not at all: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

2 Not too much: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

3 Neither differ nor not differ: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

4 Somewhat: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

5 Very much: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

96 Other: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

98 Refused: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

Placebo.

How many times in the last 14 days have you been to the grocery store?

1 Response provided [do not record response]: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

96 Other: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

97 Don’t know: Go to next question

98 Refused: Go to next question

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

If you had to guess, how many times in the last 14 days have you been to the grocery store?

1 Response provided [do not record response]: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

97 Don’t know: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

98 Refused: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

Standard GOTV Treatment.

This [VAR2], [VAR1] will be holding primary elections to select which candidates will be on the ballot this November. Many [VAR1] citizens are expected to turnout for this [VAR2]’s election. Were you aware that [VAR1]’s primary elections will be held this [VAR2]?

1 Yes: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

2 No: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

96 Other: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

98 Refused: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

99 Hung up: Thank you for your help. Goodbye

SI Expected Turnout Calculation Details

Predicted turnout is calculated using a logit model that predicts turnout using strata (state × district competitiveness × vote history) and observed covariates (state × [years since registered, years since registered missing, age, sex, sex unknown, and race indicators]) among cases in the labeled as voting condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors acknowledge funding from The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1513727113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Walton GM. The new science of wise psychological interventions. Psychol Sci. 2014;23(1):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan CJ, Walton GM, Rogers T, Dweck CS. Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(31):12653–12656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103343108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelman SA, Heyman GD. Carrot-eaters and creature-believers: The effects of lexicalization on children’s inferences about social categories. Psychol Sci. 1999;10(6):489–493. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walton GM, Banaji MR. Being what you say: The effect of essentialist linguistic labels on preferences. Soc Cogn. 2004;22(2):193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green DP, Gerber AS. Get Out the Vote! 3rd Ed Brookings Institution Press; Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arceneaux K, Nickerson DW. Who is mobilized to vote? A re-analysis of 11 field experiments. Am J Pol Sci. 2009;53(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downs A. An Economic Theory of Democracy. Addison-Wesley; Boston: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber AS, Green DP, Larimer CW. Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2008;102(1):33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panagopoulos C. Thank you for voting: Gratitude expression and voter mobilization. J Polit. 2011;73(3):707–717. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonsohn U. Small telescopes: Detectability and the evaluation of replication results. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(5):559–569. doi: 10.1177/0956797614567341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Open Science Collaboration PSYCHOLOGY. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349(6251):aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.