Significance

Birds are remarkably intelligent, although their brains are small. Corvids and some parrots are capable of cognitive feats comparable to those of great apes. How do birds achieve impressive cognitive prowess with walnut-sized brains? We investigated the cellular composition of the brains of 28 avian species, uncovering a straightforward solution to the puzzle: brains of songbirds and parrots contain very large numbers of neurons, at neuronal densities considerably exceeding those found in mammals. Because these “extra” neurons are predominantly located in the forebrain, large parrots and corvids have the same or greater forebrain neuron counts as monkeys with much larger brains. Avian brains thus have the potential to provide much higher “cognitive power” per unit mass than do mammalian brains.

Keywords: intelligence, evolution, brain size, number of neurons, birds

Abstract

Some birds achieve primate-like levels of cognition, even though their brains tend to be much smaller in absolute size. This poses a fundamental problem in comparative and computational neuroscience, because small brains are expected to have a lower information-processing capacity. Using the isotropic fractionator to determine numbers of neurons in specific brain regions, here we show that the brains of parrots and songbirds contain on average twice as many neurons as primate brains of the same mass, indicating that avian brains have higher neuron packing densities than mammalian brains. Additionally, corvids and parrots have much higher proportions of brain neurons located in the pallial telencephalon compared with primates or other mammals and birds. Thus, large-brained parrots and corvids have forebrain neuron counts equal to or greater than primates with much larger brains. We suggest that the large numbers of neurons concentrated in high densities in the telencephalon substantially contribute to the neural basis of avian intelligence.

Many birds have cognitive abilities that match or surpass those of mammals (1). Corvids and parrots appear to be cognitively superior to other birds, rivalling great apes in many psychological domains (1–3). They manufacture and use tools (4, 5), solve problems insightfully (6), make inferences about causal mechanisms (7), recognize themselves in a mirror (8), plan for future needs (9), and use their own experience to anticipate future behavior of conspecifics (10) or even humans (11), to mention just a few striking abilities. In addition, parrots and songbirds (including corvids) share with humans and a few other animal groups a rare capacity for vocal learning (12), and parrots can learn words and use them to communicate with humans (13).

Superficially, the architecture of the avian brain appears very different from that of mammals, but recent work demonstrates that, despite a lack of layered neocortex, large areas of the avian forebrain are homologous to mammalian cortex (14–16), conform to the same organizational principles (15, 17, 18), and play similar roles in higher cognitive functions (14, 19), including executive control (20, 21). However, bird brains are small and the computational mechanisms enabling corvids and parrots to achieve ape-like intelligence with much smaller brains remain unclear. The notion that higher encephalization (relative brain size deviation from brain–body allometry) endows species with improved cognitive abilities has recently been challenged by data suggesting that intelligence instead depends on the absolute number of cerebral neurons and their connections (22–25). This is in line with recent findings that absolute rather than relative brain size is the best predictor of cognitive capacity (26–28). However, although corvids and parrots feature encephalization comparable to that of monkeys and apes, their absolute brain size remains small (29, 30). The largest average brain size in corvids and parrots does not exceed 15.4 g found in the common raven (29) and 24.7 g found in the hyacinth macaw (30), respectively. Do corvids and parrots provide a strong case for reviving encephalization as a valid measure of brain functional capacity? Not necessarily: it has recently been discovered that the relationship between brain mass and number of brain neurons differs starkly between mammalian clades (31). Avian brains seem to consist of small, tightly packed neurons, and it is thus possible that they can accommodate numbers of neurons that are comparable to those found in the much larger primate brains. However, to date, no quantitative data have been available to test this hypothesis.

Here, we analyze how numbers of neurons compare across birds and mammals (32–39) of equivalent brain mass, and determine the cellular scaling rules for brains of songbirds and parrots. Using the isotropic fractionator (40), we estimated the total numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells in the cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, diencephalon, tectum, and brainstem in a sample of 11 parrot species, 13 vocal learning songbird species (including 6 corvids), and 4 additional model species representing other avian clades (Figs. S1 and S2). Because most of the cited mammalian studies analyzed cellular composition of only three brain subdivisions, namely the pallium (referred to as the cerebral cortex in those papers), the cerebellum, and rest of brain, we divided the avian brain identically to ensure an accurate comparison of neuronal numbers, densities, and relative distribution of neurons in birds and mammals. Specifically, the avian pallium (comprising the hyperpallium, mesopallium, nidopallium, arcopallium, and hippocampus) was compared with its homolog—the mammalian pallium (comprising the neocortex, hippocampus, olfactory cortices such as piriform and entorhinal cortex, and pallial amygdala) (14–16, 41). The avian subpallium (formed by the striatum, pallidum, and septum), diencephalon, tectum, and brainstem were pooled and compared with the same regions of mammalian brains that are referred to as “the rest of brain.” The cerebellum is directly compared between the two clades. The results of our study reveal that avian brains contain many more pallial neurons than equivalently sized mammalian brains.

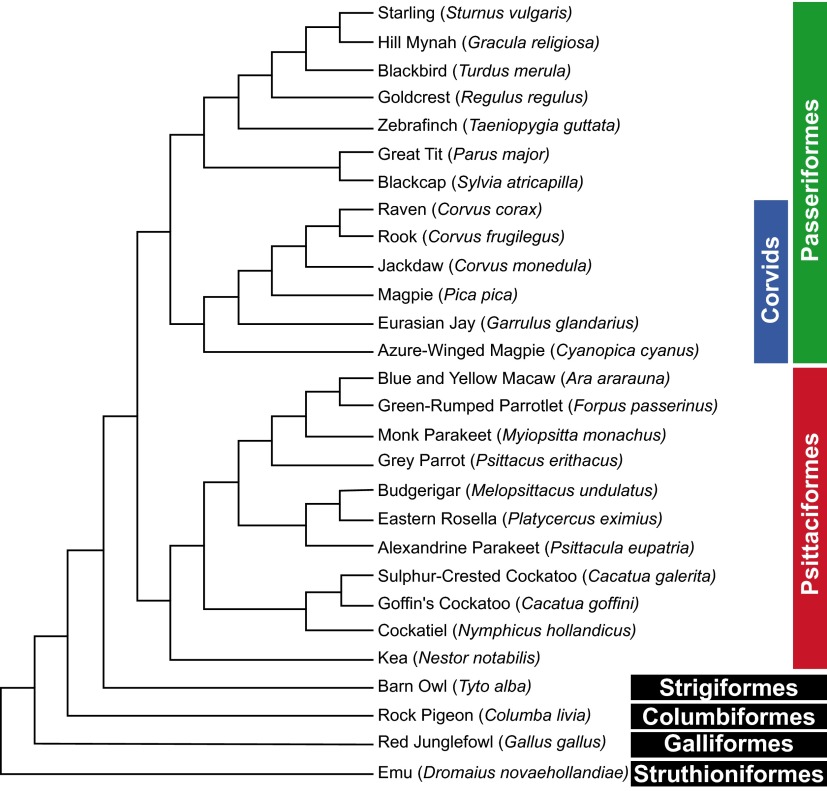

Fig. S1.

Phylogenetic relationships among the 28 species examined. The tree was constructed using birdtree.org/; its topology follows recent studies (46–49). Note that songbirds and parrots are sister groups and together with the distantly related barn owl belong to the clade core landbirds (Telluraves); the pigeon represents the Columbea, a basal clade of the Neoaves; the red junglefowl represents the Galloanseres, a sister group of Neoaves and the most basal clade of Neognathae; and the emu represents Paleognathae (tinamous and flightless ostriches), the most basal clade of extant birds (48). Also note that all passerine birds examined were vocal learners belonging to the clade Oscines.

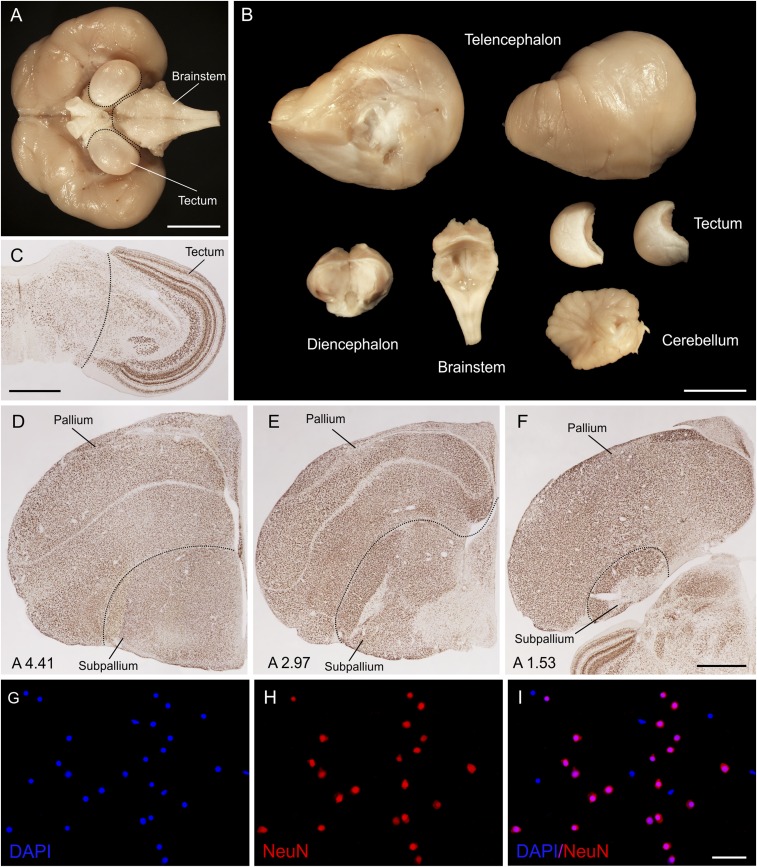

Fig. S2.

Brain dissection and labeling of neurons and nonneuronal cells. (A and B) Brain of the raven before and after the dissection. (A) Ventral side of the brain showing approximate lines of dissection of the brainstem and tectum. (B) Brain dissected into parts used for isotropic fractionation. (C) NeuN-immunolabeled transverse section of the zebra finch brain depicting the line of dissection of the tectum from the rest of the mesencephalon. (D–F) Dissection of the telencephalon into pallium and subpallium. NeuN-immunolabeled transverse sections of the zebra finch brain at rostral (D), intermediate (E), and caudal (F) telencephalic levels. Lines of dissection follow the pallial-subpallial lamina and divide the telencephalon into pallium (dorsal part) and subpallium (ventral part). Coordinates anterior to the Y point are indicated in millimeters at Bottom Left (64). (G–I) High-power micrographs showing a sample of homogenate from the telencephalon of the Eurasian jay; dissociated nuclei stained with DAPI (G) and immunolabeled with NeuN antibody (H), dual-fluorescence merge image (I). Note that neurons are double-labeled, whereas the nonneuronal cells are devoid of anti-NeuN immunoreactivity. [Scale bars: 10 mm (A and B); 1 mm (C and F); 50 µm (I).]

Results

Total Numbers of Neurons.

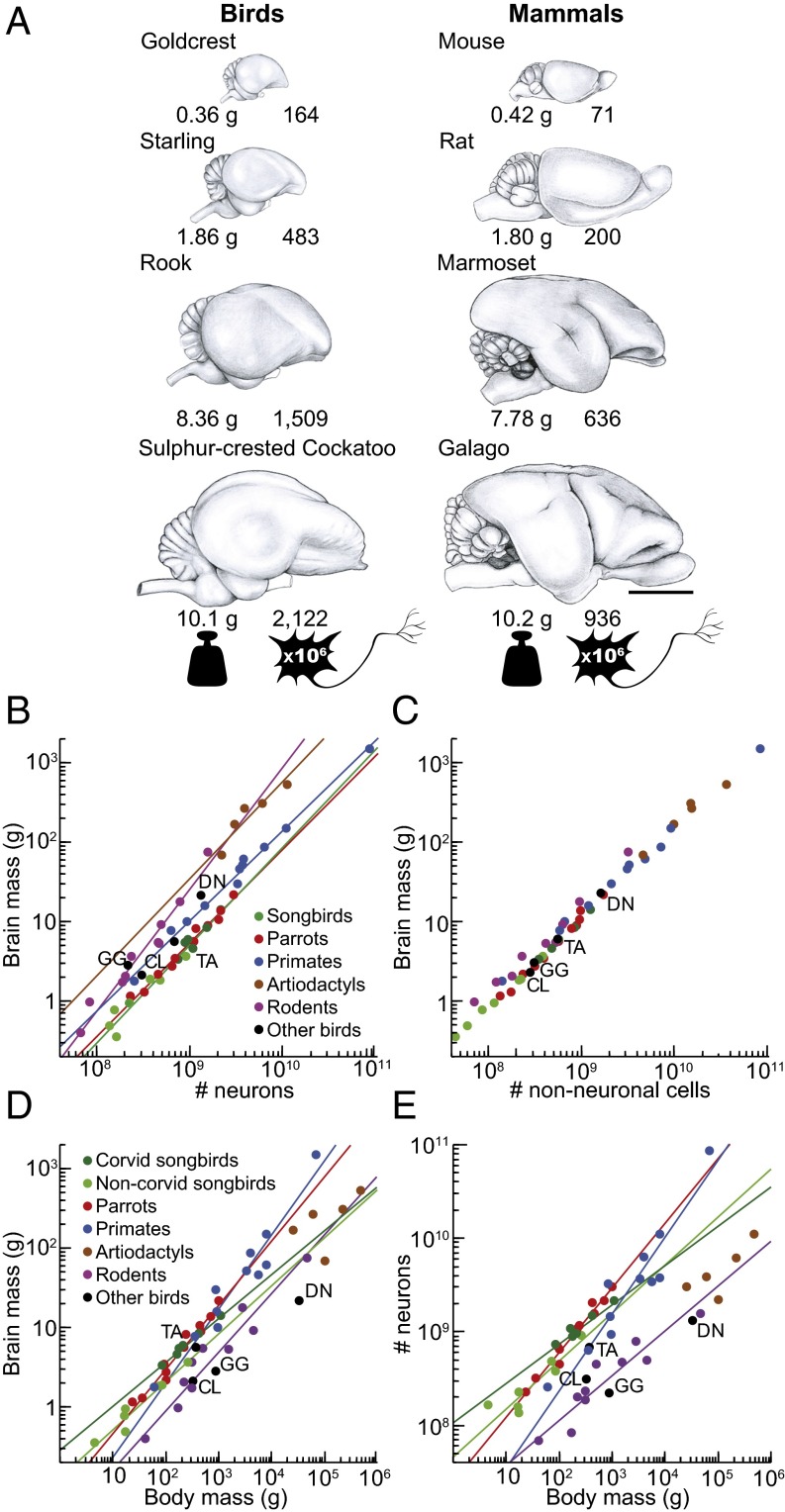

We found that the bird brains have more neurons than mammalian brains and even primate brains of similar mass (Fig. 1 A and B), and have very high neuronal densities (Fig. 2 B and C). Among the songbirds studied, weighing between 4.5 and 1,070 g, brain mass ranges from 0.36 to 14.13 g, and total numbers of neurons in the brain from 136 million to 2.17 billion (Fig. S3 and Table S1; for complete data see Datasets S1 and S2). In the parrots studied, body mass ranges between 23 and 1,008 g, brain mass from 1.15 to 20.73 g, and numbers of brain neurons from 227 million to 3.14 billion. Interestingly, the relationship between brain mass and the number of brain neurons can be described by similar power functions in these two bird groups (Table S2). Thus, songbirds and parrots with similar brain masses also have similar total numbers of brain neurons, as shown in Fig. 1B. Because the scaling exponents are significantly higher than 1.0 in both groups, any gain in number of brain neurons is accompanied by an even more pronounced gain of mass: a 10-fold increase in the number of neurons results in a 16.9- and 14.0-fold larger brain in songbirds and parrots, respectively. With their higher neuronal densities (Fig. 3 A–C), songbird and parrot brains accommodate about twice as many neurons as primate brains of the same mass and two to four times more neurons than rodent brains of equivalent mass (Fig. 1B). Songbirds and parrots also show a large brain mass for their body mass compared with nonprimate mammals (Fig. S4 A and B). Consequently, they have many more neurons than a nonprimate mammal of the same body size (Fig. 1E). For instance, the goldcrest’s body mass is ∼9-fold smaller than the mouse, but its brain has ∼2.3-fold more neurons. Large corvids and parrots possess the largest avian brains, harboring the highest absolute numbers of neurons (Fig. 1 D and E and Fig. S4C). Their total numbers of neurons are comparable to those of small monkeys or much larger ungulates (Fig. S5).

Fig. 1.

Cellular scaling rules for brains of songbirds and parrots compared with those for mammals. (A) Avian and mammalian brains depicted at the same scale. Numbers under each brain represent brain mass (in grams) and total number of brain neurons (in millions). Notice that brains of songbirds (goldcrest, starling, and rook) and parrots (cockatoo) contain more than twice as many neurons as rodent (mouse and rat) and primate (marmoset and galago) brains of similar size. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) (B) Brain mass plotted as a function of total number of neurons. Note that allometric lines for songbirds (green line) and parrots (red line) do not differ from each other, but they do differ from allometric lines for mammals (for statistics, see SI Results). (C) Brain mass plotted as a function of total number of nonneuronal cells. (D) Brain mass plotted as a function of body mass. (E) Total number of brain neurons plotted as a function of body mass. Allometric lines for the taxa examined are significantly different (for statistics, see SI Results). Each point represents the average values for one species. Data points representing noncorvid songbirds are light green, and data points representing corvid songbirds are dark green. The fitted lines represent reduced major axis (RMA) regressions and are shown only for correlations that are significant [coefficient of determination (r2) ranges between 0.831 and 0.997; P ≤ 0.021 in all cases]. Because nonneuronal scaling rules are very similar across the clades analyzed, the regression lines are omitted in C. Data for mammals are from published reports (for details, see Methods). CL, pigeon (Columba livia); DN, emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae); GG, red junglefowl (Gallus gallus); TA, barn owl (Tyto alba).

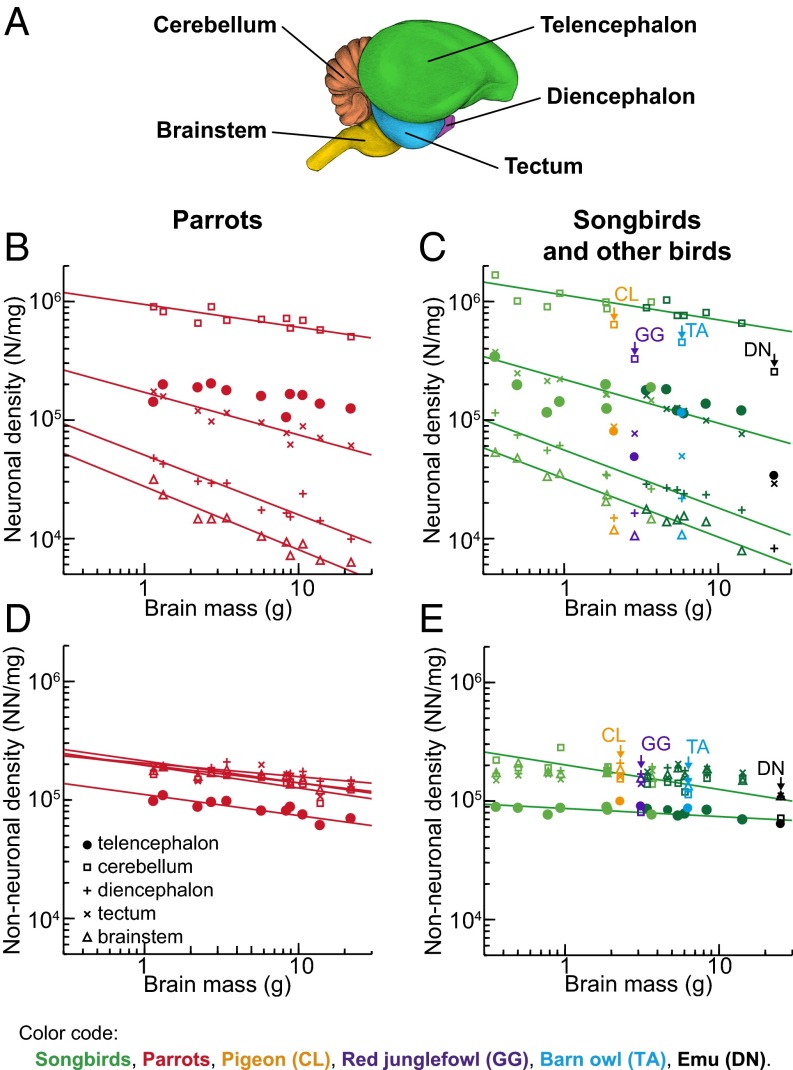

Fig. 2.

Cellular densities in avian brains. (A) Lateral view of the starling brain showing the brain regions analyzed (for details, see SI Methods and Fig. S2). Neuronal (B and C) and nonneuronal cell density (D and E) plotted as a function of brain mass. Data points representing noncorvid songbirds are light green, and data points representing corvid songbirds are dark green. All graphs are plotted using the same y-axis scale for comparison. Note that neuronal density varies greatly among principal brain divisions and decreases significantly with increasing brain mass in all divisions but the telencephalon, whereas nonneuronal cell density is similar across brain divisions and species, but lower in the telencephalon (for statistics, see SI Results). The fitted lines represent RMA regressions and are shown only for correlations that are significant (r2 ranges between 0.410 and 0.962; P ≤ 0.030 in all cases).

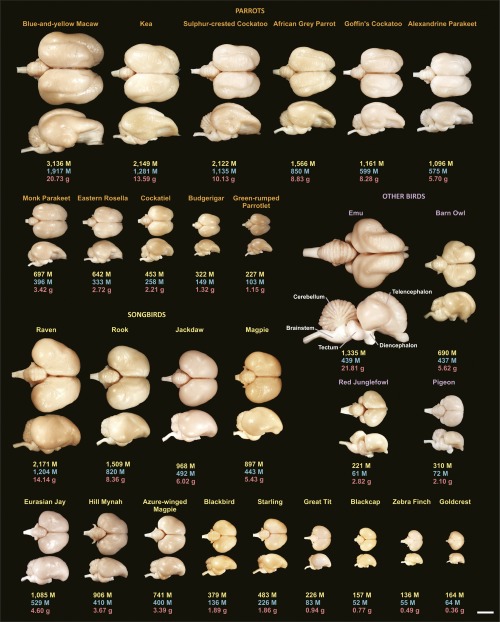

Fig. S3.

Brain size, morphology, and number of neurons for the avian species examined. Dorsal and lateral views of representative brains are accompanied by information concerning total number of brain neurons (yellow), number of pallial neurons (blue), and brain mass (red). M, million. (Scale bar, 10 mm.)

Table S1.

Cellular composition of the brains of 28 bird species

| Species | n | Body mass, g | Brain mass, g | Total neurons, ×106 | Total nonneurons, ×106 |

| Parrots | |||||

| Green-rumped parrotlet | 3 | 23.2 ± 0.7 | 1.146 ± 0.042 | 227.20 ± 3.81 | 135.00 ± 4.70 |

| Budgerigar | 3 | 35.3 ± 4.6 | 1.317 ± 0.041 | 321.82 ± 10.62 | 176.05 ± 4.26 |

| Cockatiel | 3 | 101.0 ± 4.6 | 2.205 ± 0.132 | 452.77 ± 44.51 | 234.66 ± 10.25 |

| Eastern rosella | 3 | 102.0 ± 3.4 | 2.716 ± 0.032 | 641.88 ± 79.00 | 318.17 ± 47.28 |

| Monk parakeet | 3 | 94.0 ± 1.7 | 3.420 ± 0.168 | 696.77 ± 75.26 | 393.49 ± 21.06 |

| Alexandrine parakeet | 3 | 223.0 ± 5.3 | 5.699 ± 0.492 | 1,096.26 ± 89.81 | 572.74 ± 28.11 |

| Goffin's cockatoo | 2 | 244.8 ± 3.5 | 8.275 ± 0.548 | 1,160.59 ± 101.87 | 792.22 ± 39.88 |

| Gray parrot | 2 | 453.5 ± 47.4 | 8.827 ± 0.859 | 1,565.93 ± 128.99 | 880.59 ± 2.06 |

| Sulfur-crested cockatoo | 1 | 430.0 | 10.131 | 2,121.93 | 1,001.81 |

| Kea | 1 | 708.0 | 13.593 | 2,148.67 | 975.57 |

| Blue and yellow macaw | 1 | 1,008.0 | 20.731 | 3,135.79 | 1,800.03 |

| Variation, max./min. | 43.3× | 18.1× | 13.8× | 13.3× | |

| Songbirds | |||||

| Goldcrest | 3 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 0.357 ± 0.022 | 163.87 ± 8.67 | 44.16 ± 6.57 |

| Zebra finch | 3 | 17.4 ± 2.1 | 0.494 ± 0.040 | 135.98 ± 6.82 | 59.75 ± 2.03 |

| Blackcap | 3 | 16.6 ± 1.3 | 0.774 ± 0.037 | 156.73 ± 18.91 | 86.28 ± 9.18 |

| Great tit | 3 | 17.1 ± 0.3 | 0.940 ± 0.066 | 225.98 ± 46.97 | 115.43 ± 23.43 |

| Starling | 3 | 73.1 ± 1.9 | 1.855 ± 0.047 | 482.50 ± 88.29 | 215.64 ± 13.49 |

| Blackbird | 3 | 85.0 ± 7.5 | 1.887 ± 0.117 | 379.41 ± 43.33 | 222.57 ± 27.48 |

| Azure-winged magpie | 2 | 84.1 ± 16.0 | 3.393 ± 0.486 | 740.59 ± 0.35 | 349.49 ± 33.17 |

| Hill mynah | 2 | 262.1 ± 30.7 | 3.670 ± 0.362 | 906.13 ± 45.38 | 380.79 ± 3.56 |

| Eurasian jay | 3 | 160.0 ± 12.5 | 4.597 ± 0.307 | 1,085.42 ± 159.56 | 484.42 ± 32.87 |

| Magpie | 3 | 178.6 ± 11.5 | 5.425 ± 0.617 | 897.27 ± 57.43 | 535.97 ± 15.96 |

| Jackdaw | 3 | 209.7 ± 25.1 | 6.023 ± 0.305 | 967.99 ± 106.66 | 565.92 ± 37.87 |

| Rook | 3 | 429.3 ± 35.6 | 8.357 ± 0.312 | 1,508.72 ± 38.25 | 855.55 ± 92.10 |

| Raven | 3 | 1,070.7 ± 73.2 | 14.135 ± 0.558 | 2,170.68 ± 72.67 | 1,242.85 ± 98.19 |

| Variation, max./min. | 237.9× | 39.6× | 16× | 28.1× | |

| Other birds | |||||

| Rock pigeon | 3 | 322.5 ± 22.7 | 2.095 ± 0.123 | 309.96 ± 33.33 | 262.18 ± 18.94 |

| Red junglefowl | 3 | 861.3 ± 107.3 | 2.819 ± 0.200 | 220.84 ± 44.50 | 286.68 ± 17.35 |

| Barn owl | 3 | 369.7 ± 37.7 | 5.618 ± 0.404 | 689.54 ± 39.64 | 522.49 ± 25.29 |

| Emu | 2 | 32,600.0 ± 1,414.2 | 21.811 ± 2.037 | 1,335.40 ± 29.01 | 1,528.66 ± 118.97 |

Species ordered by increasing brain size. All values are given as mean ± SD; n, number of individuals analyzed.

Table S2.

Cellular scaling rules for brains of parrots and songbirds

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Power law | r2 | P value (exponent) | 95% confidence interval |

| Parrots | |||||

| MBR | NBR | MBR = 2.669 × 10−10 × NBR1.144 | 0.979 | <0.000 1 | 1.020–1.269 |

| MTEL | NTEL | MTEL = 1.356 × 10−9 × NTEL1.075 | 0.967 | <0.000 1 | 0.928–1.221 |

| MDIE | NDIE | MDIE = 5.027 × 10−15 × NDIE2.031 | 0.827 | <0.000 1 | 1.395–2.668 |

| MTEC | NTEC | MTEC = 5.492 × 10−16 × NTEC1.998 | 0.945 | <0.000 1 | 1.645–2.350 |

| MCB | NCB | MCB = 3.030 × 10−11 × NCB1.198 | 0.974 | <0.000 1 | 1.052–1.344 |

| MBS | NBS | MBS = 1.752 × 10−20 × NBS2.968 | 0.911 | <0.000 1 | 2.304–3.633 |

| MBR | OBR | MBR = 3.267 × 10−10 × OBR1.170 | 0.989 | <0.000 1 | 1.076–1.263 |

| MTEL | OTEL | MTEL = 9.805 × 10−10 × OTEL1.126 | 0.991 | <0.000 1 | 1.043–1.208 |

| MDIE | ODIE | MDIE = 2.622 × 10−17 × ODIE1.102 | 0.989 | <0.000 1 | 1.015–1.189 |

| MTEC | OTEC | MTEC = 3.822 × 10−10 × OTEC1.160 | 0.938 | <0.000 1 | 0.943–1.380 |

| MCB | OCB | MCB = 2.440 × 10−10 × OCB1.160 | 0.970 | <0.000 1 | 1.031–1.343 |

| MBS | OBS | MBS = 2.567 × 10−10 × OBS1.186 | 0.987 | <0.000 1 | 1.081–1.288 |

| Songbirds | |||||

| MBR | NBR | MBR = 4.699 × 10−11 × NBR1.227 | 0.962 | <0.000 1 | 1.068–1.387 |

| MTEL | NTEL | MTEL = 4.678 × 10−11 × NTEL1.134 | 0.940 | <0.000 1 | 0.949–1.320 |

| MDIE | NDIE | MDIE = 2.322 × 10−16 × NDIE2.208 | 0.952 | <0.000 1 | 1.882–2.520 |

| MTEC | NTEC | MTEC = 2.024 × 10−14 ×NTEC1.736 | 0.934 | <0.000 1 | 1.440–2.033 |

| MCB | NCB | MCB = 2.013 × 10−11 × NCB1.206 | 0.972 | <0.000 1 | 1.072–1.340 |

| MBS | NBS | MBS = 2.776 × 10−17 × NBS2.445 | 0.950 | <0.000 1 | 2.081–2.810 |

| MBR | OBR | MBR = 1.536 × 10−9 × OBR1.093 | 0.998 | <0.000 1 | 1.060–1.125 |

| MTEL | OTEL | MTEL = 5.399 × 10−9 ×OTEL1.043 | 0.997 | <0.000 1 | 1.007–1.080 |

| MDIE | ODIE | MDIE = 6.292 × 10−9 × ODIE0.992 | 0.996 | <0.000 1 | 0.953–1.032 |

| MTEC | OTEC | MTEC = 1.465 × 10−9 × OTEC0.946 | 0.994 | <0.000 1 | 0.897–0.996 |

| MCB | OCB | MCB = 2.102 × 10−10 × OCB1.191 | 0.965 | <0.000 1 | 1.043–1.339 |

| MBS | OBS | MBS = 2.907 × 10−9 × OBS1.040 | 0.993 | <0.000 1 | 0.980–1.100 |

Power laws were calculated from the average species values listed in Tables S1 and S3–S5. BR, brain; BS, brainstem; CB, cerebellum; DIE, diencephalon; M, mass (in grams); N, number of neurons; O, number of other (nonneuronal) cells; r2, coefficient of determination calculated from the reduced major axis regression of species averages; TEC, tectum; TEL, telencephalon.

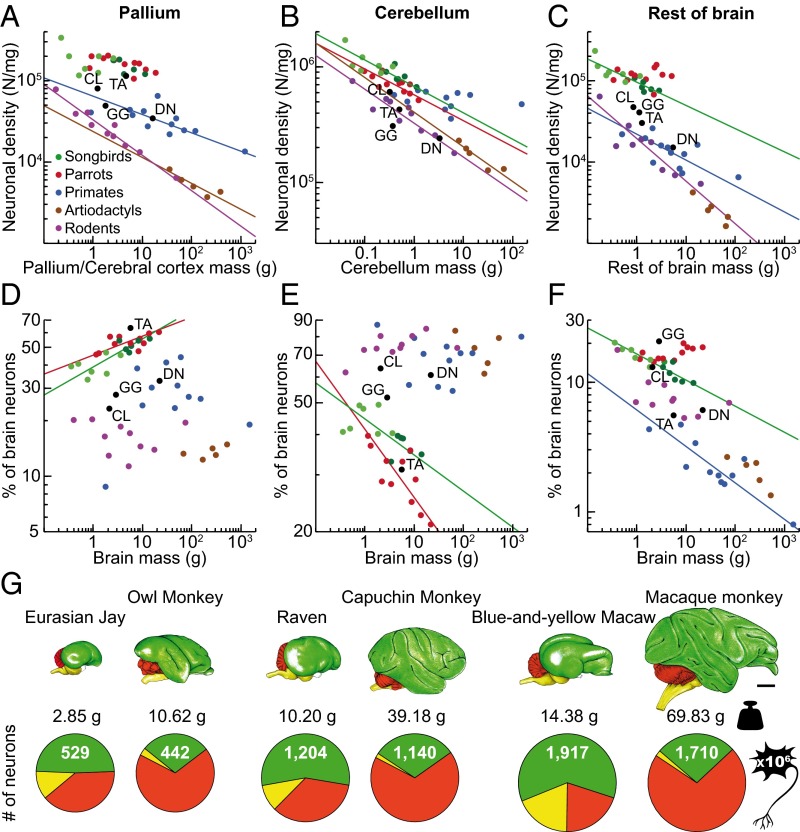

Fig. 3.

Neuronal densities and relative distribution of neurons in birds and mammals. (A–C) Neuronal densities in the pallium (A), cerebellum (B), and rest of the brain (C). Note that neuronal densities are higher in parrots and songbirds than in mammals (for statistics, see SI Results). (D–F) Average proportions of neurons contained in the pallium (D), cerebellum (E), and rest of the brain (F). Note that increasing proportions of brain neurons in the rest of the brain in parrots are attributable specifically to increasing numbers of neurons in the subpallium (Fig. 5). Data points representing noncorvid songbirds are light green, and data points representing corvid songbirds are dark green. The fitted lines represent RMA regressions and are shown only for correlations that are significant (r2 ranges between 0.389 and 0.956; P ≤ 0.033 in all cases). (G) Brains of corvids (jay and raven), parrots (macaw), and primates (monkeys) are drawn at the same scale. Numbers under each brain represent mass of the pallium (in grams) and total numbers of pallial/cortical neurons (in millions). Circular graphs show proportions of neurons contained in the pallium (green), cerebellum (red), and rest of the brain (yellow). Notice that brains of these highly intelligent birds harbor absolute numbers of neurons that are comparable, or even larger than those of primates with much larger brains. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) Data for mammals are from published reports (for details, see Methods). CL, pigeon; DN, emu; GG, red junglefowl; TA, barn owl.

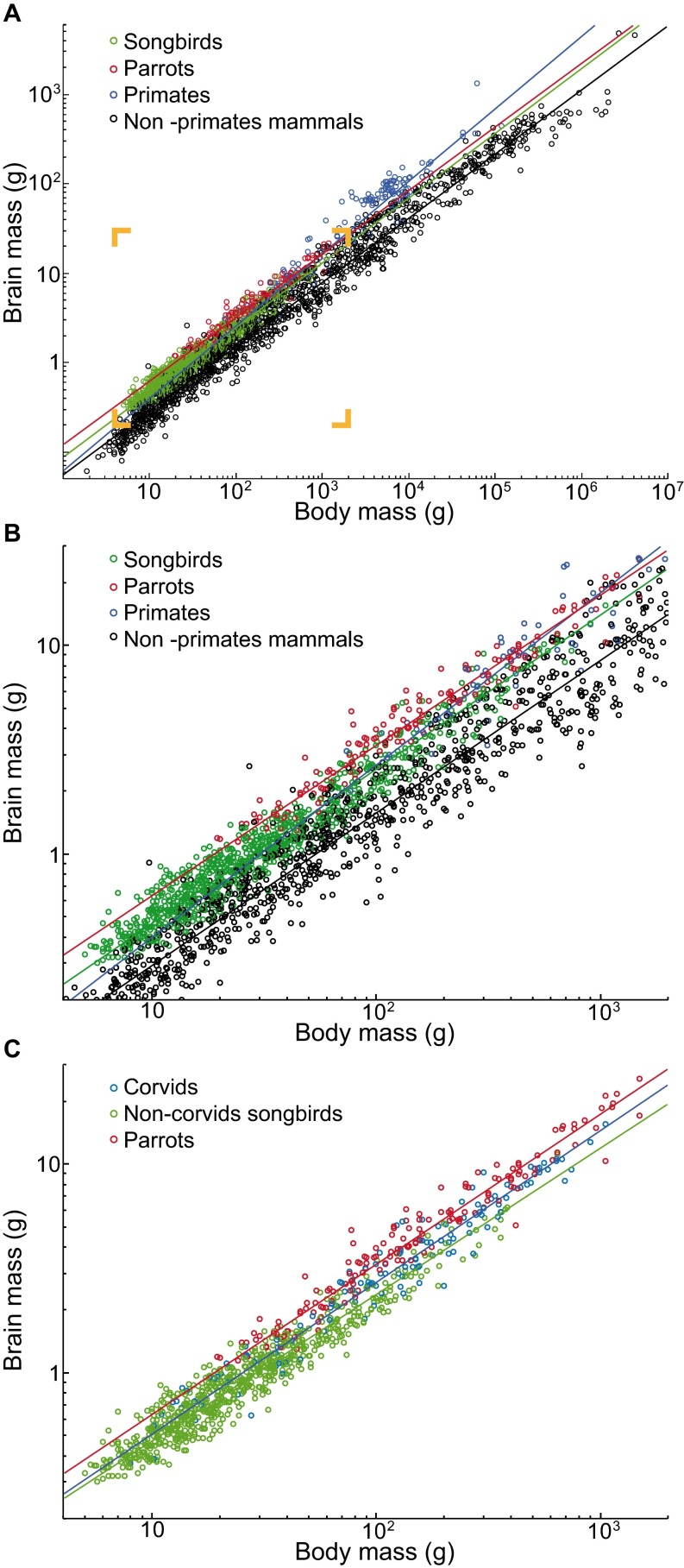

Fig. S4.

Brain–body scaling in birds and mammals. (A and B) Taxonomic differences in relative brain size among songbirds (including both Oscines and Suboscines), parrots, primates, and nonprimate mammals. Inset in A corresponds to the magnified view shown in B. Note that allometric lines for these taxonomic groups are significantly different [full-factorial ANCOVA, slopes: F(3,2618) = 78.43, P < 10−6; intercepts: F(3,2618) = 7.44, P < 10−4; post hoc analyses indicate that the regression line for primates has a different slope (P < 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons) and that parrots and songbirds have significantly larger brains for a given body mass than nonprimate mammals (P < 10−6 for both planned comparisons)]. (C) Relative brain size differences among parrots, corvids, and noncorvid songbirds. Note that allometric lines for these taxonomic groups are significantly different [slopes: F(2,996) = 4.24, P = 0.014; intercepts: F(2,996) = 5.99, P = 0.003; post hoc analyses indicate the regression line for songbirds has a different slope (P ≤ 0.045 for both pairwise comparisons) and that parrots have significantly larger brains for a given body mass than corvids (P < 10−6)]. Mean brain mass versus mean body mass for species are plotted; the fitted lines represent reduced major axis regressions. The relationship between brain mass and body mass can be described by the following power functions: songbirds, MBR = 0.087 × MBO0.737, r2 = 0.953; noncorvid songbirds, MBR = 0.096 × MBO0.698, r2 = 0.92; corvids, MBR = 0.097 × MBO0.725, r2 = 0.952; parrots, MBR = 0.123 × MBO0.716, r2 = 0.954; primates, MBR = 0.061 × MBO0.823, r2 = 0.925; nonprimate mammals, MBR = 0.055 × MBO0.730, r2 = 0.977; all values of P < 0.0001. The data on body mass and brain mass were collated from the literature (for references, see Dataset S3); cetaceans were excluded from the dataset.

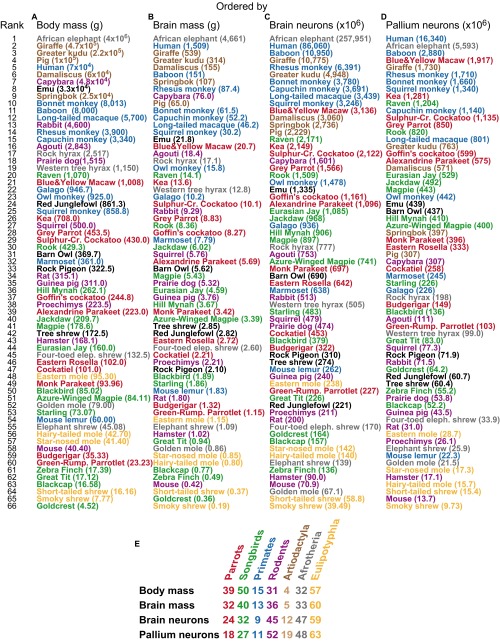

Fig. S5.

Quantitative data currently available for the avian and mammalian species examined with the isotropic fractionator. (A–D) Species ranked in descending order from the largest to the smallest body mass (A), brain mass (B), total number of brain neurons (C), and total number of pallial neurons (D). The mean values of these variables are given in brackets. (E) Median ranks for the avian and mammalian clades examined. Data for mammals are from published reports (32–39).

Relative Distribution of Mass and Neurons.

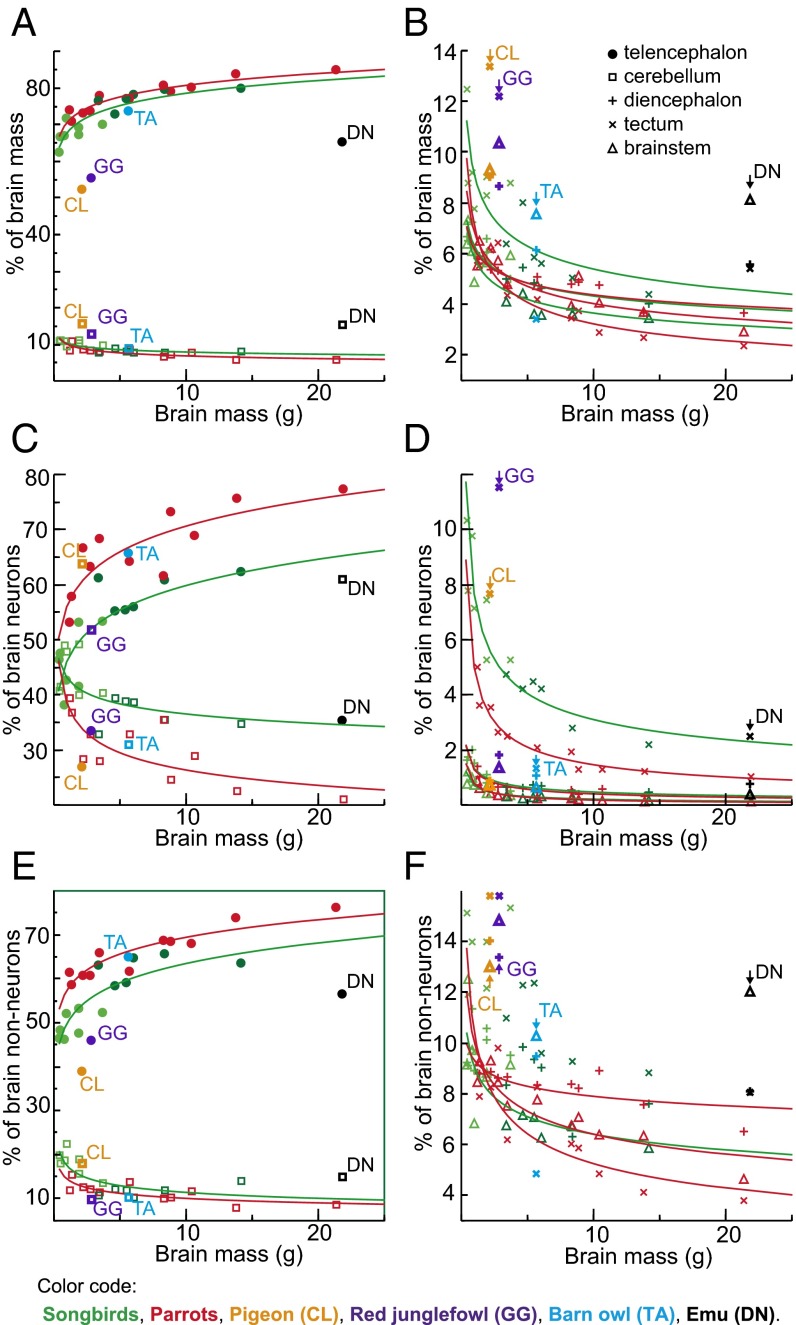

The bird/mammal comparison becomes even more striking when the relative distribution of neurons among the major brain components is taken into consideration. In the birds examined, the telencephalon mass fraction increases with brain size at the expense of all other brain components, ranging from 63% to 80% in songbirds, and from 71% to 85% in parrots (Fig. 4 A and B and Table S3); the relative proportion of the telencephalon resembles that reported for primates (42) (primates, 74 ± 5%; songbirds, 72 ± 6%; parrots, 78 ± 5%). The cerebellar mass fraction decreases from 11% to 8% in songbirds, and from 11% to 6% in parrots. Besides this, telencephalon mass scales approximately isometrically with the number of neurons, whereas all other brain components hyperscale in mass as they gain neurons (Table S2), because neuronal densities decrease and average neuronal sizes increase significantly as brains get larger within all brain parts but the telencephalon (Fig. 2 B and C). Thus, in contrast to mammals, larger brains of songbirds and parrots contain increasing proportions of neurons in the telencephalon, and correspondingly decreasing proportions of brain neurons in the cerebellum and other brain regions (Fig. 4 C and D). Neuronal densities in the avian pallium exceed those observed in the primate pallium by a factor of 3–4 (Fig. 3A). Hence, the telencephalon houses 38–62% of all brain neurons in songbirds and 53–78% in parrots (Fig. 4C); the pallium houses 33–55% in songbirds and 46–61% in parrots (Fig. 3D and Table S4). This markedly contrasts with the situation found in mammals, in which the pallium accounts for most of total brain volume, but the cerebellum houses a large majority of brain neurons (32–39) (Fig. 3 D–F). Notably, the human pallium contains a mere 19% of brain neurons but represents 82% of brain mass (38). Thus, when avian and mammalian brains of equivalent size are compared, avian pallial neurons greatly outnumber those observed in the mammalian pallium (Fig. 3G and Fig. S5). For instance, the goldcrest has ∼64 million pallial neurons, almost five times more than the mouse pallium. The raven or the kea have ∼1.2 billion pallial neurons, more than in the pallium of a capuchin monkey, and the blue-and-yellow macaw has ∼1.9 billion pallial neurons, more than in the pallium of a rhesus monkey.

Fig. 4.

Relative distribution of mass and cells in avian brains. Average percentages of mass (A and B), number of neurons (C and D), and number of nonneuronal cells (E and F) contained in the principal brain divisions relative to the whole brain in each species, plotted against brain mass. Data points representing noncorvid songbirds are light green, and data points representing corvid songbirds are dark green. The fitted lines represent RMA regressions and are shown only for correlations that are significant (r2 ranges between 0.389 and 0.956; P ≤ 0.023 in all cases). Note that both telencephalon mass fraction and proportions of neuronal and nonneuronal cells contained in the telencephalon increase with brain size.

Table S3.

Mass of the major brain divisions of 28 bird species

| Species | Telencephalon, g | Subpallium, % of Tel | Diencephalon, g | Tectum, g | Cerebellum, g | Brainstem, g |

| Parrots | ||||||

| Green-rumped parrotlet | 0.851 ± 0.039 | 16.0 | 0.067 ± 0.003 | 0.066 ± 0.004 | 0.098 ± 0.002 | 0.064 ± 0.003 |

| Budgerigar | 0.935 ± 0.039 | 17.1 | 0.078 ± 0.012 | 0.073 ± 0.002 | 0.144 ± 0.006 | 0.086 ± 0.005 |

| Cockatiel | 1.617 ± 0.098 | 15.4 | 0.119 ± 0.006 | 0.136 ± 0.010 | 0.196 ± 0.011 | 0.138 ± 0.016 |

| Eastern rosella | 2.009 ± 0.053 | 15.2 | 0.145 ± 0.002 | 0.175 ± 0.015 | 0.230 ± 0.017 | 0.156 ± 0.006 |

| Monk parakeet | 2.663 ± 0.168 | 15.9 | 0.162 ± 0.008 | 0.150 ± 0.005 | 0.281 ± 0.002 | 0.165 ± 0.013 |

| Alexandrine parakeet | 4.390 ± 0.412 | 16.7 | 0.292 ± 0.025 | 0.240 ± 0.009 | 0.506 ± 0.040 | 0.272 ± 0.013 |

| Goffin's cockatoo | 6.689 ± 0.429 | 17.7 | 0.399 ± 0.045 | 0.288 ± 0.001 | 0.571 ± 0.034 | 0.328 ± 0.038 |

| Gray parrot | 6.973 ± 0.780 | 14.8 | 0.431 ± 0.079 | 0.331 ± 0.035 | 0.638 ± 0.007 | 0.454 ± 0.028 |

| Sulfur-crested cockatoo | 8.072 | 16.2 | 0.496 | 0.304 | 0.836 | 0.423 |

| Kea | 11.383 | 16.7 | 0.504 | 0.372 | 0.825 | 0.509 |

| Blue and yellow macaw | 17.565 | 18.2 | 0.783 | 0.506 | 1.245 | 0.632 |

| Variation, max./min. | 20.7× | 11.7× | 7.7× | 12.7× | 9.9× | |

| Songbirds | ||||||

| Goldcrest | 0.225 ± 0.023 | 22.0 | 0.024 ± 0.002 | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.040 ± 0.002 | 0.023 ± 0.002 |

| Zebra finch | 0.327 ± 0.026 | 15.6 | 0.032 ± 0.006 | 0.043 ± 0.003 | 0.056 ± 0.009 | 0.036 ± 0.003 |

| Blackcap | 0.516 ± 0.036 | 12.0 | 0.056 ± 0.002 | 0.071 ± 0.003 | 0.084 ± 0.002 | 0.047 ± 0.004 |

| Great tit | 0.675 ± 0.051 | 14.0 | 0.056 ± 0.002 | 0.073 ± 0.008 | 0.090 ± 0.007 | 0.046 ± 0.004 |

| Starling | 1.287 ± 0.018 | 11.2 | 0.113 ± 0.008 | 0.155 ± 0.015 | 0.193 ± 0.013 | 0.107 ± 0.011 |

| Blackbird | 1.272 ± 0.120 | 14.2 | 0.125 ± 0.014 | 0.171 ± 0.007 | 0.213 ± 0.015 | 0.107 ± 0.009 |

| Azure-winged magpie | 2.594 ± 0.401 | 14.5 | 0.171 ± 0.014 | 0.217 ± 0.020 | 0.271 ± 0.035 | 0.140 ± 0.018 |

| Hill mynah | 2.577 ± 0.300 | 16.2 | 0.184 ± 0.007 | 0.323 ± 0.018 | 0.367 ± 0.015 | 0.218 ± 0.022 |

| Eurasian jay | 3.360 ± 0.296 | 15.1 | 0.251 ± 0.009 | 0.369 ± 0.034 | 0.411 ± 0.013 | 0.205 ± 0.004 |

| Magpie | 4.193 ± 0.520 | 11.4 | 0.263 ± 0.015 | 0.318 ± 0.035 | 0.453 ± 0.037 | 0.197 ± 0.021 |

| Jackdaw | 4.705 ± 0.221 | 11.5 | 0.280 ± 0.022 | 0.339 ± 0.010 | 0.483 ± 0.043 | 0.216 ± 0.012 |

| Rook | 6.648 ± 0.246 | 13.2 | 0.322 ± 0.013 | 0.425 ± 0.014 | 0.657 ± 0.036 | 0.306 ± 0.013 |

| Raven | 11.307 ± 0.450 | 9.8 | 0.570 ± 0.086 | 0.623 ± 0.073 | 1.145 ± 0.116 | 0.49 ± 0.012 |

| Variation, max./min. | 50.3× | 23.7× | 14.5× | 28.6× | 21.3× | |

| Other birds | ||||||

| Rock pigeon | 1.095 ± 0.090 | 16.5 | 0.190 ± 0.006 | 0.281 ± 0.016 | 0.332 ± 0.013 | 0.196 ± 0.014 |

| Red junglefowl | 1.567 ± 0.162 | 14.8 | 0.245 ± 0.014 | 0.345 ± 0.022 | 0.369 ± 0.024 | 0.293 ± 0.010 |

| Barn owl | 4.141 ± 0.328 | 7.0 | 0.347 ± 0.007 | 0.192 ± 0.006 | 0.510 ± 0.080 | 0.427 ± 0.011 |

| Emu | 14.238 ± 1.515 | 8.8 | 1.218 ± 0.072 | 1.184 ± 0.152 | 3.399 ± 0.181 | 1.773 ± 0.116 |

Species ordered by increasing brain size. All values are given as mean ± SD.

Table S4.

Number of neurons in the major brain divisions of 28 bird species

| Species | Telencephalon, ×106 | Subpallium, % of Tel | Diencephalon, ×106 | Tectum, ×106 | Cerebellum, ×106 | Brainstem, ×106 |

| Parrots | ||||||

| Green-rumped parrotlet | 120.84 ± 4.68 | 14.4 | 3.25 ± 0.49 | 11.44 ± 1.04 | 89.62 ± 5.08 | 2.05 ± 0.21 |

| Budgerigar | 186.00 ± 4.09 | 19.9 | 3.34 ± 0.16 | 11.72 ± 2.09 | 118.73 ± 8.31 | 2.03 ± 0.46 |

| Cockatiel | 301.81 ± 40.57 | 14.4 | 3.64 ± 1.68 | 16.11 ± 1.11 | 129.15 ± 7.77 | 2.06 ± 0.76 |

| Eastern rosella | 406.32 ± 77.24 | 18.0 | 4.30 ± 0.77 | 16.98 ± 2.62 | 211.98 ± 25.42 | 2.31 ± 0.49 |

| Monk parakeet | 476.50 ± 73.49 | 16.9 | 4.78 ± 1.33 | 17.49 ± 0.76 | 195.53 ± 22.69 | 2.47 ± 0.44 |

| Alexandrine parakeet | 703.96 ± 94.37 | 18.4 | 5.16 ± 0.96 | 22.95 ± 4.78 | 361.36 ± 10.29 | 2.84 ± 0.52 |

| Goffin's cockatoo | 715.08 ± 95.62 | 16.2 | 6.63 ± 0.37 | 22.71 ± 2.02 | 413.10 ± 7.67 | 3.07 ± 0.24 |

| Gray parrot | 1,147.54 ± 73.25 | 25.9 | 6.75 ± 2.71 | 20.90 ± 2.53 | 387.40 ± 51.18 | 3.35 ± 0.69 |

| Sulfur-crested cockatoo | 1,490.59 | 23.8 | 12.05 | 27.06 | 588.41 | 3.82 |

| Kea | 1,630.49 | 21.4 | 7.13 | 26.57 | 481.14 | 3.35 |

| Blue and yellow macaw | 2,459.15 | 22.0 | 7.85 | 31.22 | 633.52 | 4.06 |

| Variation, max./min. | 20.4× | 2.4× | 2.7× | 7.1× | 2× | |

| Songbirds | ||||||

| Goldcrest | 76.13 ± 5.77 | 15.7 | 2.73 ± 0.17 | 16.99 ± 1.39 | 66.78 ± 3.28 | 1.26 ± 0.10 |

| Zebra finch | 64.66 ± 2.84 | 14.6 | 2.40 ± 0.42 | 10.62 ± 0.50 | 56.61 ± 9.84 | 1.69 ± 0.46 |

| Blackcap | 59.71 ± 6.23 | 12.6 | 3.15 ± 0.24 | 15.34 ± 2.31 | 76.94 ± 13.02 | 1.58 ± 0.14 |

| Great tit | 96.38 ± 27.43 | 13.9 | 3.47 ± 0.67 | 16.19 ± 0.91 | 108.27 ± 20.71 | 1.67 ± 0.52 |

| Starling | 257.08 ± 66.07 | 12.0 | 4.00 ± 0.88 | 25.44 ± 0.54 | 193.74 ± 25.00 | 2.24 ± 0.58 |

| Blackbird | 157.63 ± 13.12 | 13.6 | 4.26 ± 0.55 | 28.26 ± 3.53 | 186.73 ± 33.99 | 2.52 ± 0.034 |

| Azure-winged magpie | 454.25 ± 36.08 | 12.0 | 4.99 ± 1.34 | 35.35 ± 0.60 | 243.49 ± 35.05 | 2.51 ± 0.65 |

| Hill mynah | 484.29 ± 49.32 | 15.3 | 4.90 ± 0.22 | 47.97 ± 0.33 | 365.74 ± 4.07 | 3.22 ± 0.24 |

| Eurasian jay | 600.49 ± 139.10 | 11.9 | 6.75 ± 0.66 | 45.95 ± 2.22 | 429.35 ± 28.75 | 2.88 ± 0.47 |

| Magpie | 497.94 ± 26.98 | 11.0 | 6.83 ± 1.14 | 40.44 ± 2.80 | 349.25 ± 27.82 | 2.82 ± 0.14 |

| Jackdaw | 541.37 ± 63.55 | 9.2 | 6.82 ± 1.55 | 40.94 ± 4.55 | 375.46 ± 41.89 | 3.39 ± 0.73 |

| Rook | 917.85 ± 68.58 | 10.6 | 7.56 ± 1.48 | 42.72 ± 3.59 | 536.28 ± 29.31 | 4.30 ± 0.45 |

| Raven | 1,355.34 ± 73.26 | 11.2 | 10.15 ± 2.99 | 47.65 ± 7.31 | 753.64 ± 27.34 | 3.90 ± 0.18 |

| Variation, max./min. | 22.7× | 4.2× | 4.5× | 13.3× | 3.1× | |

| Other birds | ||||||

| Rock pigeon | 83.35 ± 20.53 | 13.8 | 2.81 ± 0.69 | 23.76 ± 2.69 | 197.72 ± 11.37 | 2.31 ± 0.31 |

| Red junglefowl | 73.79 ± 2.46 | 17.8 | 4.02 ± 0.76 | 25.50 ± 3.26 | 114.45 ± 39.59 | 3.08 ± 0.57 |

| Barn owl | 453.73 ± 13.53 | 3.6 | 7.54 ± 1.19 | 9.33 ± 1.22 | 214.31 ± 32.07 | 4.63 ± 0.68 |

| Emu | 471.57 ± 3.54 | 6.8 | 10.22 ± 2.48 | 33.72 ± 3.74 | 814.61 ± 17.66 | 5.28 ± 1.60 |

Species ordered by increasing brain size. All values are given as mean ± SD.

Subpallium.

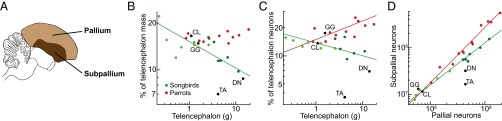

Although once believed to constitute almost the entire avian telencephalon (14), the subpallium (basal ganglia homolog) accounts only for 10–22% of total telencephalon volume in songbirds and for 15–18% in parrots, and houses only 9–16% of telencephalic neurons in songbirds and 14–24% in parrots (Tables S3 and S4). In songbirds, both the relative mass of the subpallium and the fraction of telencephalic neurons contained within it decrease with increasing telencephalon size (Fig. 5 B and C). In parrots, in contrast, the relative mass remains constant and neuronal fraction increases with telencephalon size. Therefore, large-brained parrots have a relatively larger subpallium within the telencephalon that accommodates relatively more telencephalic neurons than that of large-brained songbirds (Fig. 5 B–D), implying that parrots have evolved a specific, previously unrecognized cerebrotype (43) distinguished by a higher number of neurons allocated to the subpallium. Because subpallial structures play an important role in sensory and motor learning and execution of motor behavior (15, 44), we suggest that the relatively enlarged subpallium in large parrots is likely associated with their greater learning skills, including vocal learning, and enhanced foot and beak dexterity (5, 6, 13, 45).

Fig. 5.

Subpallium in avian telencephalon. (A) Diagram of sagittal section through the zebra finch brain showing relative position and size of the pallium and subpallium. (B and C) Average percentages of mass (B), number of neurons (C) contained in the subpallium relative to the whole telencephalon in each species, plotted against telencephalon mass. (D) Relationship between numbers of subpallial and pallial neurons. Note that, in parrots, the number of neurons in the subpallium increases faster than in the pallium (scaling exponent = 1.19 ± 0.13), whereas an opposite trend is observed in songbirds (scaling exponent = 0.91 ± 0.1). The fitted lines represent RMA regressions and are shown only for correlations that are significant (r2 ranges between 0.379 and 0.981; P ≤ 0.025 in all cases). Songbirds shown in green (data points representing noncorvids are light green, and data points representing corvids are dark green), parrots in red, and other birds in black. CL, pigeon; DN, emu; GG, red junglefowl; TA, barn owl.

Nonneuronal Scaling Rules.

Although neuronal scaling rules for avian brains differ from those for mammalian brains (Fig. 1B), nonneuronal scaling rules are shared between the two vertebrate classes (Fig. 1C and Table S2). In line with data from all mammals analyzed so far (32–39), the densities of nonneuronal (glial and endothelial) cells remain similar across bird species in all brain structures, except for the telencephalon, where nonneuronal cell density appears to be distinctively lower (Fig. 2 D and E). The latter may be a specific avian feature, as it has not been observed in mammals (31).

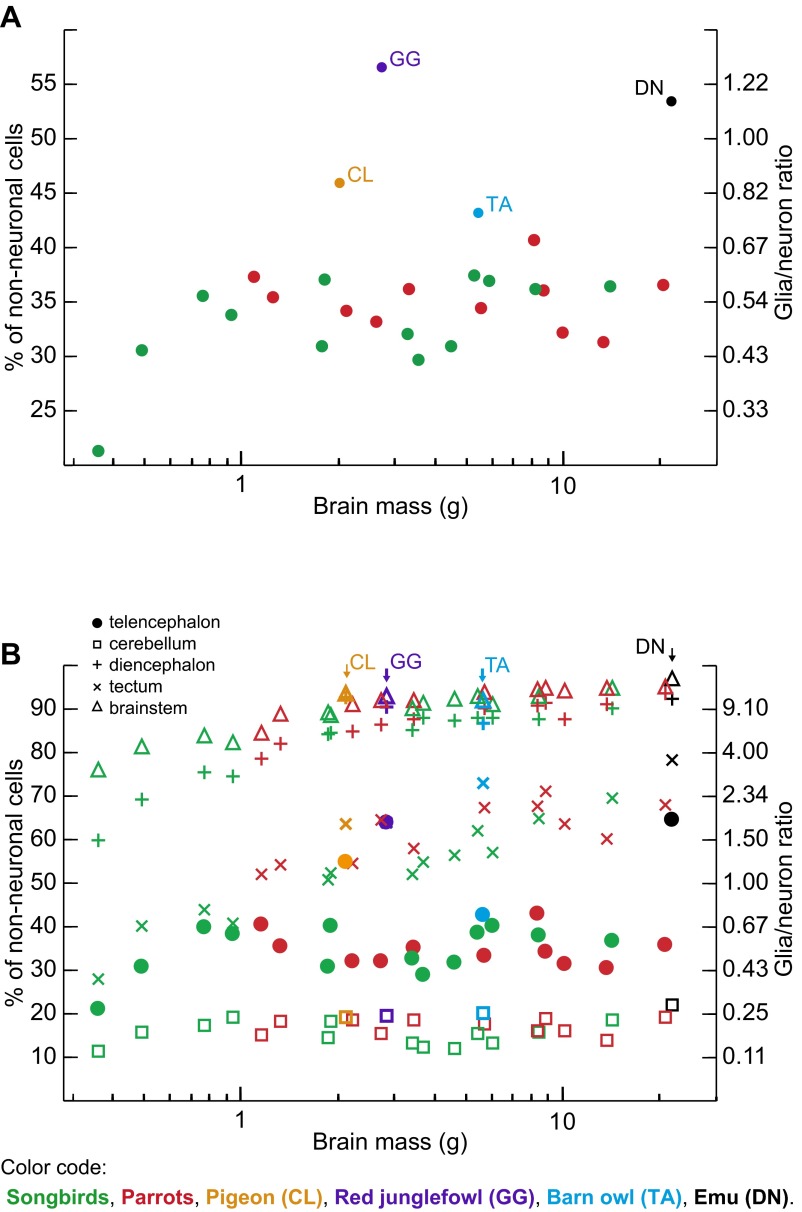

Glia/Neuron Ratio.

Neurons outnumber nonneuronal cells in both bird groups examined (Fig. S6A and Table S5). The proportion of nonneuronal cells in the brain ranges between 21% and 37% in songbirds and from 31% to 41% in parrots. Hence, the maximal glia/neuron ratio (if all nonneuronal cells were glial cells) for the whole brain ranges from 0.27 to 0.59 in songbirds and from 0.44 to 0.69 in parrots. Like in mammals (32–39, 46), the proportion of nonneuronal cells is very small in the cerebellum, varying between 12% and 19% in songbirds and between 14% and 19% in parrots, but, in contrast to mammals, nonneuronal cells also constitute a minor cellular fraction in the telencephalon, representing 21–40% of cells in songbirds and 31–43% of cells in parrots (Fig. S6B). Nonneuronal cells predominate in the remaining brain regions analyzed, representing in songbirds and parrots, respectively, 60–90% and 79–94% of all cells in the diencephalon, 28–70% and 52–71% of all cells in the tectum, and 76–95% and 85–95% of all cells in the brainstem (Fig. S6B). The fact that neurons constitute an extremely small cellular fraction in the diencephalon of many avian species is an unexpected finding. Given that nonneuronal cell densities are similar to those found in most other brain divisions investigated (Fig. 2 D and E), this is unlikely to be due to a technical error. The numeric preponderance of neurons over nonneuronal cells in the bird brain as a whole is therefore due to the disproportionately large numbers of neurons in the telencephalon and cerebellum.

Fig. S6.

Glia/neuron ratios for the avian species examined. Each point represents the average proportion of nonneuronal cells (left axis) and the glia/neuron ratio (right axis) for one species, plotted against the average brain mass for that species. Songbirds are shown in green, parrots in red, and other birds in black. (A) The overall glia/neuron ratio in the brain. Note the higher proportion of nonneuronal cells in all outgroup taxa. (B) Variation in the glia/neuron ratio among the principal brain divisions investigated. Note that nonneuronal cells constitute a minor cellular fraction in the telencephalon of all species except three representatives of basal bird lineages—the emu, the red junglefowl, and the pigeon. Also note the high proportion of nonneuronal cells in the brainstem and the diencephalon.

Table S5.

Number of nonneuronal cells in the brain divisions of 28 bird species

| Species | Telencephalon, ×106 | Subpallium, % of Tel | Diencephalon, ×106 | Tectum, ×106 | Cerebellum, ×106 | Brainstem, ×106 |

| Parrots | ||||||

| Green-rumped parrotlet | 83.01 ± 2.45 | 15.0 | 11.95 ± 1.05 | 12.42 ± 2.35 | 16.18 ± 0.21 | 11.45 ± 0.98 |

| Budgerigar | 103.22 ± 2.23 | 20.2 | 15.49 ± 3.29 | 13.92 ± 2.91 | 27.08 ± 4.59 | 16.35 ± 1.72 |

| Cockatiel | 142.78 ± 14.01 | 19.1 | 20.83 ± 2.14 | 19.45 ± 2.96 | 29.72 ± 4.78 | 21.88 ± 3.05 |

| Eastern rosella | 193.56 ± 40.48 | 15.3 | 27.47 ± 4.39 | 31.22 ± 0.85 | 38.96 ± 2.26 | 26.97 ± 4.38 |

| Monk parakeet | 259.75 ± 20.81 | 16.1 | 34.24 ± 0.53 | 24.40 ± 1.78 | 45.40 ± 2.50 | 29.70 ± 1.39 |

| Alexandrine parakeet | 353.72 ± 34.43 | 16.2 | 47.91 ± 5.07 | 47.38 ± 8.48 | 79.03 ± 7.98 | 44.70 ± 1.78 |

| Goffin's cockatoo | 544.50 ± 7.14 | 24.6 | 66.51 ± 9.81 | 48.00 ± 0.51 | 79.60 ± 15.59 | 53.60 ± 7.85 |

| Gray parrot | 602.93 ± 2.07 | 10.2 | 72.44 ± 5.46 | 51.88 ± 6.34 | 90.70 ± 2.96 | 62.63 ± 4.71 |

| Sulfur-crested cockatoo | 688.63 | 17.7 | 87.57 | 47.89 | 114.59 | 63.12 |

| Kea | 721.18 | 19.6 | 73.85 | 40.18 | 78.33 | 62.03 |

| Blue and yellow macaw | 1,383.27 | 16.3 | 115.1 | 66.95 | 152.48 | 82.23 |

| Variation, max./min. | 16.7× | 9.6× | 5.4× | 9.4× | 7.2× | |

| Songbirds | ||||||

| Goldcrest | 20.48 ± 5.03 | 21.6 | 4.09 ± 0.75 | 6.69 ± 0.19 | 8.85 ± 1.62 | 4.05 ± 0.37 |

| Zebra finch | 28.89 ± 1.23 | 19.5 | 5.45 ± 1.06 | 7.13 ± 0.99 | 10.79 ± 2.49 | 7.49 ± 0.92 |

| Blackcap | 39.8 ± 3.12 | 11.5 | 9.79 ± 0.79 | 12.08 ± 2.93 | 16.19 ± 2.57 | 8.41 ± 0.40 |

| Great tit | 60.11 ± 18.23 | 17.1 | 10.29 ± 1.75 | 11.20 ± 0.77 | 25.94 ± 5.47 | 7.90 ± 1.12 |

| Starling | 115.05 ± 8.09 | 14.6 | 21.84 ± 1.57 | 26.31 ± 1.42 | 33.68 ± 5.78 | 18.76 ± 1.34 |

| Blackbird | 106.02 ± 16.65 | 18.2 | 23.54 ± 0.36 | 31.18 ± 3.71 | 42.11 ± 8.19 | 19.72 ± 0.81 |

| Azure-winged magpie | 220.70 ± 14.36 | 15.9 | 29.20 ± 9.40 | 38.51 ± 4.45 | 37.46 ± 0.75 | 23.62 ± 5.70 |

| Hill mynah | 199.22 ± 8.05 | 18.6 | 36.30 ± 3.52 | 58.41 ± 1.74 | 51.85 ± 0.90 | 35.00 ± 0.12 |

| Eurasian jay | 282.53 ± 34.69 | 16.1 | 47.84 ± 3.71 | 59.62 ± 7.81 | 59.59 ± 12.83 | 34.83 ± 3.65 |

| Magpie | 316.64 ± 9.68 | 11.6 | 50.33 ± 5.41 | 66.29 ± 3.52 | 64.73 ± 8.41 | 37.99 ± 1.72 |

| Jackdaw | 366.72 ± 40.30 | 13.5 | 51.35 ± 6.03 | 54.36 ± 1.95 | 57.82 ± 3.60 | 35.67 ± 1.47 |

| Rook | 562.20 ± 79.47 | 14.6 | 54.05 ± 3.73 | 79.57 ± 10.68 | 102.14 ± 13.90 | 57.59 ± 9.50 |

| Raven | 790.64 ± 80.16 | 12.2 | 94.86 ± 13.90 | 110.13 ± 22.37 | 173.96 ± 4.03 | 73.27 ± 3.51 |

| Variation, max./min. | 38.6× | 23.2× | 16.5× | 19.7× | 18.1× | |

| Other birds | ||||||

| Rock pigeon | 102.02 ± 16.85 | 17.6 | 36.85 ± 1.58 | 41.55 ± 0.74 | 47.61 ± 3.58 | 34.16 ± 5.04 |

| Red junglefowl | 131.98 ± 9.48 | 17.0 | 38.42 ± 4.70 | 45.39 ± 7.09 | 28.28 ± 9.67 | 42.63 ± 0.98 |

| Barn owl | 339.01 ± 16.56 | 8.2 | 49.74 ± 4.50 | 25.39 ± 2.60 | 54.52 ± 10.61 | 53.82 ± 7.26 |

| Emu | 865.37 ± 74.72 | 11.2 | 124.24 ± 10.16 | 123.63 ± 16.28 | 231.05 ± 2.58 | 184.36 ± 20.40 |

Species ordered by increasing brain size. All values are given as mean ± SD.

Corvid Brain as a Scaled-Up Songbird Brain.

When considering the numbers of neurons and nonneuronal cells and their allocations to the major brain divisions, the same scaling rules apply to the brains of corvids and noncorvid songbirds (Figs. 1–5 and Table S2). Thus, it is not cellular composition but encephalization that sets corvids apart from other songbirds. Technically, residual brain mass calculated from regressions for all songbirds is significantly larger in corvids than in noncorvid songbirds [species examined in this study: t(2,11) = 2.542, P = 0.03, Fig. 1D; species collated from literature: t(2,848) = 7.55, P < 10−6, Fig. S4C]. Because corvid brains tend to be larger than brains of noncorvid songbirds for any given body size (Fig. 1D and Fig. S4C), corvids have larger total numbers of neurons than noncorvid songbirds of the same body size (Fig. 1E). We suggest that corvid brains are scaled-up songbird brains, just as humans brains are to brains of nonhuman primates (38, 47), and that large absolute numbers of neurons endow corvids with superior cognitive abilities.

Comparison with Other Birds.

The similarity of neuronal scaling rules between songbirds and parrots is not too surprising, considering their close phylogenetic relationship (48–51). The examination of outgroup taxa, however, suggests that, as in mammals (31), different neuronal scaling rules apply to various bird lineages. The closest relative to songbirds and parrots of the species sampled, the barn owl (Fig. S1) (48–51) resembles songbirds and parrots in terms of encephalization (Fig. 1D), relative telencephalon size (Fig. 4A), and neuronal densities in the telencephalon and diencephalon (Fig. 2C), but has a proportionally smaller subpallium (Fig. 5B) and lower neuronal densities in the tectum and cerebellum (Fig. 2C). The emu, the red junglefowl, and the pigeon, all species representing more basal bird lineages (Fig. S1), share lower degree of encephalization (Fig. 1D), a proportionally smaller telencephalon (Fig. 4A), small telencephalic and dominant cerebellar neuronal fractions (Fig. 4C), generally lower neuronal densities (Fig. 2C), and larger glia/neuron ratios (Fig. S6). Therefore, their brains harbor much smaller absolute numbers of neurons than brains of equivalently sized songbirds or parrots. For instance, although a red junglefowl is ∼50-fold heavier than a great tit, both birds have approximately the same number of brain neurons (Fig. 1E and Fig. S3). Remarkably, even in these basal birds, neuronal densities in the pallium are still comparable to those observed in the primate cortex (Fig. 3A). Thus, high neuronal density in the telencephalon appears characteristic of all birds. This means that neuronal densities in the primate pallium are matched by those of chicken and emu, but surpassed by those of songbirds and parrots.

Discussion

Assuming that brains of parrots and songbirds have diverged from the presumptive ancestral avian pattern found in all representatives of basal bird lineages examined and characterized by a mammal-like numerical preponderance of cerebellar neurons, we suggest that birds generally have higher neuronal densities than mammals, and further that parrots and songbirds have acquired an expanded telencephalon with increased neuronal densities. Two proximate, synergistic mechanisms likely contributed to this evolutionary process. First, just like the expansion of neocortex in primates (52), the expansion of the telencephalon in parrots and songbirds is associated with delayed and protracted neurogenesis, an expanded subventricular zone, and delayed neuronal maturation (53–55). It has been suggested that extensive posthatching neurogenesis and brain maturation promote learning from conspecifics and may have facilitated the emergence of specialized circuits that mediate vocal learning and possibly also other flexible and innovative behaviors (56). Second, analyses of brain gene expression profiles strongly suggest that songbirds and parrots independently evolved vocal learning pathways by duplication of preexisting, surrounding motor circuits (57, 58). Intriguingly, parrot pallial song nuclei underwent a further duplication event to evolve a unique additional circuit, the so-called shell song system, which seems to be particularly well developed in large-brained parrots (45). What ultimate mechanisms drive the evolution of the enlarged, neuron-rich telencephalon, which sets parrots and songbirds apart from the more basal birds we examined, remains poorly understood. We suggest that this expansion has been due to simultaneous selective pressures on cognitive enhancement and an evolutionary constraint on brain size, which may stem from the constraints on body size imposed by active flight. Altriciality and the extended parental care that has developed in avian ancestors simultaneously relaxed constraints on the duration of ontogenesis, a precondition for telencephalic expansion by the mechanisms described above (56). Moreover, a short neck relative to many other bird lineages may have reduced biophysical constraints on head size (cf. ref. 59).

Our finding of greater than primate-like numbers of neurons in the pallium of parrots and songbirds suggests that the large absolute numbers of telencephalic neurons in these two clades provide a means of increasing computational capacity, supporting their advanced behavioral and cognitive complexity, despite their physically smaller brains. Moreover, a short interneuronal distance, the corollary of the extremely high packing densities of their telencephalic neurons, likely results in a high speed of information processing, which may further enhance cognitive abilities of these birds. Thus, the nuclear architecture of the avian brain appears to exhibit more efficient packing of neurons and their interconnections than the layered architecture of the mammalian neocortex.

Further comparative studies on additional species are required to determine whether the high neuronal densities and preferential allocation of neurons to the telencephalon represent unique features of songbirds, parrots, and perhaps some other clades like owls, or have evolved multiple times independently in large-brained birds. More detailed quantitative studies should assess the distribution of neurons among various telencephalic regions involved in specific circuits subserving specific functions. The results, combined with behavioral studies, will enable us to determine the causal relationships between neuronal numbers and densities and perceptual, cognitive, and executive/motor abilities, and greatly advance our understanding of potential mechanisms linking neuronal density with information-processing capacity.

Methods

Experimental procedures were all approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Charles University in Prague. Altogether, 73 birds belonging to 28 species were used in this study (Table S1). Animals were killed by an overdose of halothane and perfused with 4% (wt/wt) paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed, postfixed for an additional 7–21 d, and dissected into the cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, diencephalon, tectum, and brainstem. In one individual per species, one hemisphere was dissected into the pallium and the subpallium. In these brain components, the total numbers of cells, neurons, and nonneuronal cells were estimated following the procedure of isotropic fractionation described earlier (40). The reduced major axis regressions to power functions were calculated to describe how structure mass, numbers of cells, and densities are interrelated across species. Analysis of covariance was used to compare scaling among groups (taxonomic orders or brain regions). To compare relative brain size between corvid and noncorvid songbirds, we computed t test on the residuals of a log–log regression of brain mass against body mass (residual brain mass, hereafter). For the comparison with cellular scaling rules reported previously for mammals, the reduced major axis regressions were calculated from quantitative data published for primates (33, 37, 38), rodents excluding the naked mole-rat (32, 39), and artiodactyls (36). In addition, the published quantitative data for Eulipothyphla (34) and Afrotheria (35) were used for comparison in Fig. S5. Further details are provided in Supporting Information.

SI Methods

Animals.

Three individuals per species were collected with some exceptions for large parrots, two songbird species, and the emu, in which only one or two birds were examined. The following species were purchased from local breeders: all species of parrots, zebra finch, azure-winged magpie, common hill myna, raven, emu, red junglefowl, and barn owl. According to some authors, the genetic integrity of the red junglefowl Gallus gallus is endangered due to hybridization with domestic or feral chickens at the edge of fragmented forests (60). Although we thus cannot exclude admixture of genes from domestic or feral chicken, the red junglefowl used in this study appeared to have a pure wild phenotype. The remaining birds were wild-caught in Czech Republic (Permission No. 00212/CS/2013 and 446/2013). All birds were sexually mature or at least had adult-like size and plumage coloration. We determined the sex of all animals upon dissection and found that we had included both males and females in the analysis. The sample sizes were too small to analyze sex differences.

Animals were killed by an overdose of halothane. They were weighed and immediately perfused transcardially with warmed PBS containing 0.1% heparin followed by cold phosphate-buffered 4% (wt/wt) paraformaldehyde solution. Skulls were partially opened and postfixed for 30–60 min, after which brains were dissected and weighed. Brains were postfixed for additional 7–21 d and then dissected. All procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Charles University in Prague, Ministry of Culture (Permission No. 47987/2013) and Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic (Permission No. 53404/ENV/13-2299/630/13).

Dissection.

Brains were dissected into distinct components using the Olympus SZX 16 stereomicroscope. The cerebral hemispheres were detached from the diencephalon by a straight cut separating the subpallium from the thalamus. The tectum (optic lobe) was bilaterally excised from the surface of the brainstem. The excised parts included most of the tectal gray, optic tectum, and torus semicircularis. Both left and right tectum were processed together. The cerebellum was cut off at the surface of the brainstem. Finally, the remaining structures were dissected into diencephalon (rostral part) and brainstem (caudal part) along the plane connecting the posterior commissure dorsally and hypothalamus–mesencephalon boundary ventrally. For most individuals, only one cerebral hemisphere was processed, because in our preliminary studies we detected negligible differences between left and right hemisphere mass and cell numbers. In one individual per species, the second hemisphere was dissected into the pallium and the subpallium. These hemispheres were embedded in agarose and sectioned on a vibratome at 300–500 μm (depending on size of a hemisphere) in the coronal plane. Under oblique transmitted light at the stereomicroscope and with the use of a microsurgical knife (Stab Knife Straight; 5.5 mm; REF 7516; Surgical Specialties Corporation), we manually dissected the pallium from subpallium on each section by cutting along the pallial-subpallial lamina, as defined by Reiner et al. (41). The subpallium included all major subpallial cell groups enumerated therein; the remaining parts of the telencephalon constituted the pallium. The dissected structures were dried with paper towel, weighed, incubated in 30% (wt/wt) sucrose solution until they sank, then transferred into antifreeze (30% glycerol, 30% ethylene glycol, 40% phosphate buffer), and frozen for further processing.

Isotropic Fractionator.

We estimated total numbers of cells, neurons, and nonneuronal cells following the procedure of isotropic fractionation described earlier (40). Briefly, each dissected brain division was homogenized in 40 mM sodium citrate with 1% Triton X-100 using Tenbroeck tissue grinders (Wheaton). When turned into an isotropic suspension of isolated cell nuclei, homogenates were stained with the florescent DNA marker DAPI, adjusted to a defined volume, and kept homogenous by agitation. The total number of nuclei in suspension, and therefore the total number of cells in original tissue, was estimated by determining density of nuclei in small fractions drawn from a homogenate. At least four 10-µL aliquots were sampled and counted using a Neubauer improved counting chamber (BDH; Dagenham) with an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with epifluorescence and appropriate filter settings (Olympus filters U-MWU2 for DAPI and U-MWG2 for Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary antibodies); additional aliquots (typically two to five) were assessed when needed to reach the coefficient of variation among counts ≤ 0.15. Once the total cell number was known, the proportion of neurons was determined by immunocytochemical detection of neuronal nuclear marker NeuN (61). This neuron-specific protein was detected by the mouse monoclonal antibody anti-NeuN (clone A60; Chemicon; dilution, 1:800), which was recently characterized by Western blotting with chick brain samples and shown to react with a protein of the same molecular weight as in mammals (62), indicating that it does not cross-react with other proteins in birds. The binding sites of the primary antibody were revealed by Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies; dilution, 1:500). An electronic hematologic counter (Alchem Grupa) was used to count simultaneously DAPI-labeled and NeuN-immunopositive nuclei in the Neubauer chamber. A minimum of 500 nuclei was counted to estimate percentage of double-labeled neuronal nuclei. Numbers of nonneuronal cells were derived by subtraction.

Data Analysis.

All analyses were performed using average values for each species; variables were log-transformed before the subsequent statistical analyses. Correlations between variables were assessed using nonparametric Spearman rank test. If a significance criterion of P < 0.05 was reached, the reduced major axis regressions were calculated to describe how structure mass, numbers of cells, and densities are interrelated across species. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare scaling among groups (taxonomic orders or brain regions). The significant interaction between categorical and continuous predictors in the full-factorial ANCOVA demonstrates statistically different slopes of the regression lines among groups and precludes the direct comparison of the magnitude of differences among groups based just on the differences in intercepts. In these cases, the group responsible for the significant interaction was excluded from the ANCOVA model, and, subsequently, the effect of categorical predictor was tested across groups with statistically homogenous slopes, and their differences were compared based on differences in the intercepts. The planned comparisons of least-squares means was used to examine significant pairwise differences. To compare relative brain size between corvid and noncorvid songbirds, we computed t test on the residuals of a log–log regression of brain mass against body mass (residual brain mass, hereafter). For the comparison with cellular scaling rules reported previously for mammals, the reduced major axis regressions were calculated from quantitative data published for primates (33, 37, 38), rodents excluding the naked mole-rat (32, 39), and artiodactyls (36). In addition, the published quantitative data for Eulipothyphla (34) and Afrotheria (35) were used for comparison in Fig. S4.

The regressions were calculated using RMA for JAVA 1.21 (63); ANCOVA and t test, using Statistica 10.0 (Stat Soft); and all other analyses were performed in JMP 10.0 (SAS Institute).

SI Results

The results of the ANCOVA are summarized below for selected, important comparisons among taxonomic orders and brain regions. They are listed in order, in which they appear in the figures.

Ad Fig. 1.

(B) Allometric lines for songbirds (green line) and parrots (red line) do not differ from each other [full-factorial ANCOVA, slopes: F(1,20) = 0.537, P = 0.47; intercepts: F(1,20) = 0.580, P = 0.46], but they do differ from allometric lines for mammals [slopes: F(4,40) = 4.290, P = 0.006; intercepts: F(4,40) = 3.595, P = 0.014; post hoc analyses indicate that the regression line for rodents has a different slope and that parrots and songbirds have significantly smaller brains for a given number of neurons than primates and artiodactyls, P < 10−6 for all planned comparisons].

(E) Allometric lines for the taxa examined are significantly different [slopes: F(5,38) = 3.653, P = 0.009; intercepts: F(5,38) = 2.558, P = 0.043; post hoc analyses indicate that the regression line for primates has a different slope and that parrots and songbirds have a significantly higher number of neurons for a given body mass than rodents and artiodactyls, P < 0.001 for all planned comparisons].

Ad Fig. 2.

(B and C) Neuronal density varies significantly among principal brain divisions in both parrots [slopes: F(4,45) = 16.2, P < 10−6; intercepts: F(4,45) = 233.0, P < 10−6] and songbirds [slopes: F(4,55) = 14.4, P < 10−6; intercepts: F(4,55) = 523.9, P < 10−6].

(D and E) Comparison of the telencephalon with data pooled for the all other structures examined indicate that nonneuronal cell density is significantly lower in the telencephalon than in the remaining brain divisions in both parrots [slopes: F(1,51) = 0.00, P = 0.995; intercepts: F(1,51) = 58.94, P < 10−6] and songbirds [slopes: F(1,61) = 0.0, P = 0.838; intercepts: F(1,61) = 238.0, P < 10−6].

Ad Fig. 3.

(A) Pallial neuronal densities are significantly higher in parrots and songbirds than in mammals [slopes: F(4,41) = 5.948, P = 0.0007; intercepts: F(4,41) = 75.688, P = < 10−6; post hoc analyses indicate that the regression line for rodents has a different slope and that parrots and songbirds have significantly higher telencephalic neuronal densities than primates and artiodactyls, P < 10−6 for all planned comparisons].

(B) Cerebellar neuronal densities tend to be higher in parrots and songbirds than in mammals [slopes: F(4,40) = 7.84, P < 10−4; intercepts: F(4,40) = 24.71, P = < 10−6; post hoc analyses indicate that the regression line for primates has a different slope and that parrots and songbirds have significantly higher cerebellar neuronal densities than rodents and artiodactyls, P < 10−4 for all planned comparisons].

(C) Neuronal densities in the rest of brain are significantly higher in parrots and songbirds than in mammals [slopes: F(4,41) = 4.876, P = 0.003; intercepts: F(4,41) = 86.875, P = < 10−6; post hoc analyses indicate that the regression line for parrots and for rodents differ in slope from other regression lines and that songbirds have significantly higher neuronal densities than primates and artiodactyls, P < 10−6 for all planned comparisons].

Ad Fig. 5.

(C) Allometric lines for songbirds (green line) and parrots (red line) differ significantly in slope [F(1,20) = 17.232, P = 0.0005].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Güntürkün, H. J. ten Donkelaar, T. Bugnyar, N. C. Bennett, M. Prevorovsky, and K. Kverkova for reading of the manuscript and discussions; V. Miller and T. Hajek for logistic support; Y. Zhang and V. Blahova for their assistance with experiments; Z. Pavelkova and B. Strakova for collecting data on avian and mammalian brain and body mass from the literature; L. Kratochvil for methodological advice; P. Benda and J. Mateju for help with acquiring animal experiment approvals; R. Vodicka for assistance with anaesthesia of the emu; and P. Benda and J. Mlikovsky for providing access to dissection facilities of the National Museum of the Czech Republic. This project was funded by Czech Science Foundation (14-21758S) (to P.N.), Grant Agency of Charles University (851613) (to M.K.), Specific Research Grant from Charles University in Prague (SVV 260 313/2016) (to M.K.), the European Social Fund and the state budget of the Czech Republic (CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0022) (to S.O.)., the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (to S.H.-H.), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (to S.H.-H.), and the James S. McDonnell Foundation (to S.H.-H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1517131113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Emery NJ. Cognitive ornithology: The evolution of avian intelligence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1465):23–43. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery NJ, Clayton NS. The mentality of crows: Convergent evolution of intelligence in corvids and apes. Science. 2004;306(5703):1903–1907. doi: 10.1126/science.1098410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton NS, Emery NJ. Avian models for human cognitive neuroscience: A proposal. Neuron. 2015;86(6):1330–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weir AA, Chappell J, Kacelnik A. Shaping of hooks in New Caledonian crows. Science. 2002;297(5583):981. doi: 10.1126/science.1073433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auersperg AMI, Szabo B, von Bayern AMP, Kacelnik A. Spontaneous innovation in tool manufacture and use in a Goffin’s cockatoo. Curr Biol. 2012;22(21):R903–R904. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber L, Gajdon GK. Technical intelligence in animals: The kea model. Anim Cogn. 2006;9(4):295–305. doi: 10.1007/s10071-006-0033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor AH, Miller R, Gray RD. New Caledonian crows reason about hidden causal agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(40):16389–16391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208724109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prior H, Schwarz A, Güntürkün O. Mirror-induced behavior in the magpie (Pica pica): Evidence of self-recognition. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(8):e202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raby CR, Alexis DM, Dickinson A, Clayton NS. Planning for the future by western scrub-jays. Nature. 2007;445(7130):919–921. doi: 10.1038/nature05575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery NJ, Clayton NS. Effects of experience and social context on prospective caching strategies by scrub jays. Nature. 2001;414(6862):443–446. doi: 10.1038/35106560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugnyar T, Schwab C, Schloegl C, Kotrschal K, Heinrich B. Ravens judge competitors through experience with play caching. Curr Biol. 2007;17(20):1804–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis ED. Learned birdsong and the neurobiology of human language. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1016:749–777. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pepperberg IM. The Alex Studies: Cognitive and Communicative Abilities of Grey Parrots. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvis ED, et al. Avian Brain Nomenclature Consortium Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate brain evolution. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(2):151–159. doi: 10.1038/nrn1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis ED, et al. Global view of the functional molecular organization of the avian cerebrum: Mirror images and functional columns. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521(16):3614–3665. doi: 10.1002/cne.23404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfenning AR, et al. Convergent transcriptional specializations in the brains of humans and song-learning birds. Science. 2014;346(6215):1256846. doi: 10.1126/science.1256846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanahan M, Bingman VP, Shimizu T, Wild M, Güntürkün O. Large-scale network organization in the avian forebrain: A connectivity matrix and theoretical analysis. Front Comput Neurosci. 2013;7:89. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2013.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calabrese A, Woolley SM. Coding principles of the canonical cortical microcircuit in the avian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(11):3517–3522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408545112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirsch JA, Güntürkün O, Rose J. Insight without cortex: Lessons from the avian brain. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17(2):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Güntürkün O. The avian “prefrontal cortex” and cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15(6):686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veit L, Nieder A. Abstract rule neurons in the endbrain support intelligent behaviour in corvid songbirds. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2878. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Striedter GF. Principles of Brain Evolution. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth G, Dicke U. Evolution of the brain and intelligence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(5):250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herculano-Houzel S. Brains matter, bodies maybe not: The case for examining neuron numbers irrespective of body size. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1225:191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dicke U, Roth G. 2016. Neuronal factors determining high intelligence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371(1685):20150180.

- 26.Deaner RO, Isler K, Burkart J, van Schaik C. Overall brain size, and not encephalization quotient, best predicts cognitive ability across non-human primates. Brain Behav Evol. 2007;70(2):115–124. doi: 10.1159/000102973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLean EL, et al. The evolution of self-control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(20):E2140–E2148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323533111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens JR. 2014. Evolutionary pressures on primate intertemporal choice. Proc Biol Sci 281(1786):20140499.

- 29.Mlikovsky J. Brain size and forearmen magnum area in crows and allies (Aves: Corvidae) Acta Soc Zool Bohem. 2003;67(1-4):203–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwaniuk AN, Dean KM, Nelson JE. Interspecific allometry of the brain and brain regions in parrots (Psittaciformes): Comparisons with other birds and primates. Brain Behav Evol. 2005;65(1):40–59. doi: 10.1159/000081110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herculano-Houzel S, Manger PR, Kaas JH. Brain scaling in mammalian evolution as a consequence of concerted and mosaic changes in numbers of neurons and average neuronal cell size. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:77. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herculano-Houzel S, Mota B, Lent R. Cellular scaling rules for rodent brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(32):12138–12143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604911103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herculano-Houzel S, Collins CE, Wong P, Kaas JH. Cellular scaling rules for primate brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3562–3567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611396104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarko DK, Catania KC, Leitch DB, Kaas JH, Herculano-Houzel S. Cellular scaling rules of insectivore brains. Front Neuroanat. 2009;3:8. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.008.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neves K, et al. Cellular scaling rules for the brain of afrotherians. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:5. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazu RS, Maldonado J, Mota B, Manger PR, Herculano-Houzel S. Cellular scaling rules for the brain of Artiodactyla include a highly folded cortex with few neurons. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:128. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabi M, et al. Cellular scaling rules for the brains of an extended number of primate species. Brain Behav Evol. 2010;76(1):32–44. doi: 10.1159/000319872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azevedo FA, et al. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513(5):532–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herculano-Houzel S, et al. Updated neuronal scaling rules for the brains of Glires (rodents/lagomorphs) Brain Behav Evol. 2011;78(4):302–314. doi: 10.1159/000330825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herculano-Houzel S, Lent R. Isotropic fractionator: A simple, rapid method for the quantification of total cell and neuron numbers in the brain. J Neurosci. 2005;25(10):2518–2521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4526-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiner A, et al. Avian Brain Nomenclature Forum Revised nomenclature for avian telencephalon and some related brainstem nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2004;473(3):377–414. doi: 10.1002/cne.20118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark DA, Mitra PP, Wang SSH. Scalable architecture in mammalian brains. Nature. 2001;411(6834):189–193. doi: 10.1038/35075564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwaniuk AN, Hurd PL. The evolution of cerebrotypes in birds. Brain Behav Evol. 2005;65(4):215–230. doi: 10.1159/000084313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reiner A, Medina L, Veenman CL. Structural and functional evolution of the basal ganglia in vertebrates. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28(3):235–285. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chakraborty M, et al. Core and shell song systems unique to the parrot brain. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0118496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herculano-Houzel S. The glia/neuron ratio: How it varies uniformly across brain structures and species and what that means for brain physiology and evolution. Glia. 2014;62(9):1377–1391. doi: 10.1002/glia.22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herculano-Houzel S. The human brain in numbers: A linearly scaled-up primate brain. Front Hum Neurosci. 2009;3:31. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.031.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hackett SJ, et al. A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history. Science. 2008;320(5884):1763–1768. doi: 10.1126/science.1157704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jetz W, Thomas GH, Joy JB, Hartmann K, Mooers AO. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature. 2012;491(7424):444–448. doi: 10.1038/nature11631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jarvis ED, et al. Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science. 2014;346(6215):1320–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1253451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prum RO, et al. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature. 2015;526(7574):569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature15697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146(1):18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Charvet CJ, Striedter GF. Developmental species differences in brain cell cycle rates between northern bobwhite quail (Colinus virginianus) and parakeets (Melopsittacus undulatus): Implications for mosaic brain evolution. Brain Behav Evol. 2008;72(4):295–306. doi: 10.1159/000184744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charvet CJ, Striedter GF. Developmental origins of mosaic brain evolution: Morphometric analysis of the developing zebra finch brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;514(2):203–213. doi: 10.1002/cne.22005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charvet CJ, Striedter GF. Causes and consequences of expanded subventricular zones. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34(6):988–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charvet CJ, Striedter GF. Developmental modes and developmental mechanisms can channel brain evolution. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:4. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feenders G, et al. Molecular mapping of movement-associated areas in the avian brain: A motor theory for vocal learning origin. PLoS One. 2008;3(3):e1768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chakraborty M, Jarvis ED. 2015. Brain evolution by brain pathway duplication. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370(1684):20150056.

- 59.Taylor MP, Wedel MJ. Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks. PeerJ. 2013;1:e36. doi: 10.7717/peerj.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peterson AT, Brisbin IL. Genetic endangerment of wild red junglefowl Gallus gallus? Bird Conserv Int. 1998;8(04):387–394. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116(1):201–211. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mezey S, et al. Postnatal changes in the distribution and density of neuronal nuclei and doublecortin antigens in domestic chicks (Gallus domesticus) J Comp Neurol. 2012;520(1):100–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.22696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bohonak AJ, van der Linde K. 2004 RMA: Software for reduced major axis regression, Java version. Available at www.kimvdlinde.com/professional/rma.html. Accessed January 5, 2015.

- 64.Nixdorf-Bergweiler B, Bischof H-J. 2007 A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Brain of the Zebra Finch, Taeniopygia guttata, with Special Emphasis on Telencephalic Visual and Song System Nuclei in Transverse and Sagittal Sections (National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD). Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2356/. Accessed March 3, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.