Significance

We describe the development of a small molecule that mediates the degradation of bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins and its application in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Few therapeutic options exist to treat CRPC, especially CRPC tumors expressing constitutively active androgen receptor (AR) splice variants that lack the ligand-binding domain and can effect androgen-independent transactivation of target genes. Importantly, we demonstrate that targeted degradation of BET proteins using proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology causes cell death in cultured prostate cancer cells and results in tumor growth inhibition or regression in mouse models of CRPC, including models that express high levels of AR splice variant 7. Our work thus contains a significant potential therapeutic advance in the treatment of this cancer.

Keywords: BET, BRD4, protein degradation, prostate, PROTAC

Abstract

Prostate cancer has the second highest incidence among cancers in men worldwide and is the second leading cause of cancer deaths of men in the United States. Although androgen deprivation can initially lead to remission, the disease often progresses to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), which is still reliant on androgen receptor (AR) signaling and is associated with a poor prognosis. Some success against CRPC has been achieved by drugs that target AR signaling, but secondary resistance invariably emerges, and new therapies are urgently needed. Recently, inhibitors of bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family proteins have shown growth-inhibitory activity in preclinical models of CRPC. Here, we demonstrate that ARV-771, a small-molecule pan-BET degrader based on proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology, demonstrates dramatically improved efficacy in cellular models of CRPC as compared with BET inhibition. Unlike BET inhibitors, ARV-771 results in suppression of both AR signaling and AR levels and leads to tumor regression in a CRPC mouse xenograft model. This study is, to our knowledge, the first to demonstrate efficacy with a small-molecule BET degrader in a solid-tumor malignancy and potentially represents an important therapeutic advance in the treatment of CRPC.

Dysregulation of signaling mediated by the androgen receptor (AR) is among the best-established mechanisms underlying prostate cancer (PCa). Androgen ablation by surgical or chemical castration brings about remission of localized PCa in the great majority of early-stage patients (1–3). However, the disease eventually progresses to a more aggressive form known as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), which presents clinically as an increase in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) while circulating testosterone remains at castration levels (4). Although the etiology of disease progression can be complex, it is thought that high AR expression resensitizes tumor cells to low levels of adrenal androgens (5). Although CRPC is now known to be reliant on androgen signaling, traditional endocrine therapies are ineffective against it (6). Until recently, the only treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for metastatic CRPC were microtubule-disrupting taxanes such as docetaxel and cabazitaxel, which provide only a modest survival benefit (7). Second-generation AR-axis inhibitors such as abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide have now been granted FDA approval against metastatic CRPC. Although both drugs result in improved survival among patients, approximately a third of patients demonstrate no serum PSA response to these drugs (8–10). The rest acquire secondary resistance, marked by a restoration of AR signaling and serum PSA levels (11). This reactivation of AR signaling is partly mediated by constitutively active AR splice variants that lack the ligand-binding domain (12–14). Interestingly, a growing body of literature suggests that these truncated AR variants require functional full-length AR (FL-AR) to mediate drug resistance. Specifically, the AR variants AR-V7 and ARv567es have been shown to heterodimerize with FL-AR, enable its nuclear localization, and facilitate the expression of canonical AR target genes (15, 16). Similarly, simultaneous antisense-oligo–mediated down-regulation of AR-V7 and FL-AR offers no additional benefit over FL-AR down-regulation alone in enzalutamide-resistant LnCaP-derived xenografts (17). These data taken together argue strongly for the development of new strategies to tackle AR signaling in CRPC (18).

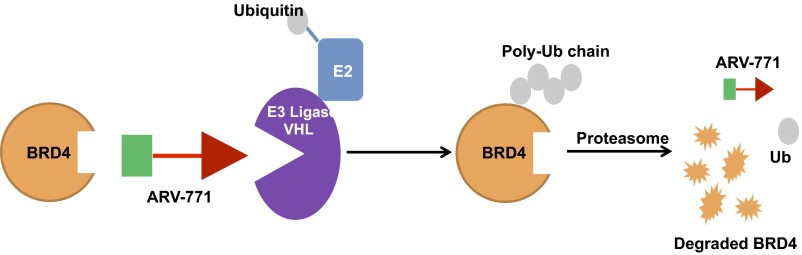

Inhibition of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family of proteins has been proposed as an epigenetic approach in tackling CRPC. BET inhibitors result in growth inhibition in tumor models of CRPC (19–21). In addition, BET proteins 2, 3, and 4 (BRD2/3/4) bind AR directly, in a manner that is disrupted by BET inhibitors (20). This disruption results in abrogation of AR-mediated transcription, thus making BET proteins an attractive target in CRPC. Interestingly, although BET inhibitors attenuate AR transcriptional activity, their effect on AR protein levels is controversial. Two recent studies claim that BET inhibition does not alter FL-AR levels (19, 20). However, one report shows attenuation of both FL-AR and AR-V7 levels (22). We and others have recently developed small-molecule degraders of BET proteins (23–25). These heterobifunctional molecules, known as “proteolysis targeting chimeras” (PROTACs), contain a ligand for a target protein of interest connected via a linker to a ligand for an E3 ubiquitin ligase (26, 27). Thereby, treatment of cells with a PROTAC results in the formation of a trimeric complex that allows ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the target protein via the proteasome (Fig. S1) (28). We previously demonstrated that a BET PROTAC that recruits the E3 ligase cereblon (CRBN) results in potent BET degradation and sustained inhibition of downstream signaling in Burkitt lymphoma cell lines (23). A second group developed CRBN-based BET PROTACs in parallel and demonstrated tumor growth inhibition (TGI) with intraperitoneal delivery in an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subcutaneous xenograft mouse model (25).

Fig. S1.

BRD4 PROTAC schematic.

In this study, we demonstrate that ARV-771, a von Hippel–Landau (VHL) E3 ligase-based BET PROTAC, is highly active against cellular models of CRPC. ARV-771 in these cells results in rapid BET protein degradation with DC50 (the drug concentration that results in 50% protein degradation) values <1 nM. Interestingly, ARV-771–mediated BET degradation leads to the decrease of both FL-AR and AR-V7 at the transcript level. In contrast, treatment of CRPC cells with BET inhibitors leads to the suppression of AR-V7 but not of FL-AR levels. Moreover, ARV-771 causes significantly greater apoptotic cell death than a BET inhibitor. Finally, subcutaneous delivery of ARV-771 is efficacious in two different mouse models of CRPC and results in tumor regression in enzalutamide-resistant 22Rv1 xenografts. Thus, this study validates BET protein degradation as a promising clinical strategy against metastatic CRPC and demonstrates the feasibility of treating solid-tumor malignancies with small-molecule–mediated protein degradation using PROTACs.

Results

ARV-771 Is a Potent BET Degrader in Cellular Models of CRPC.

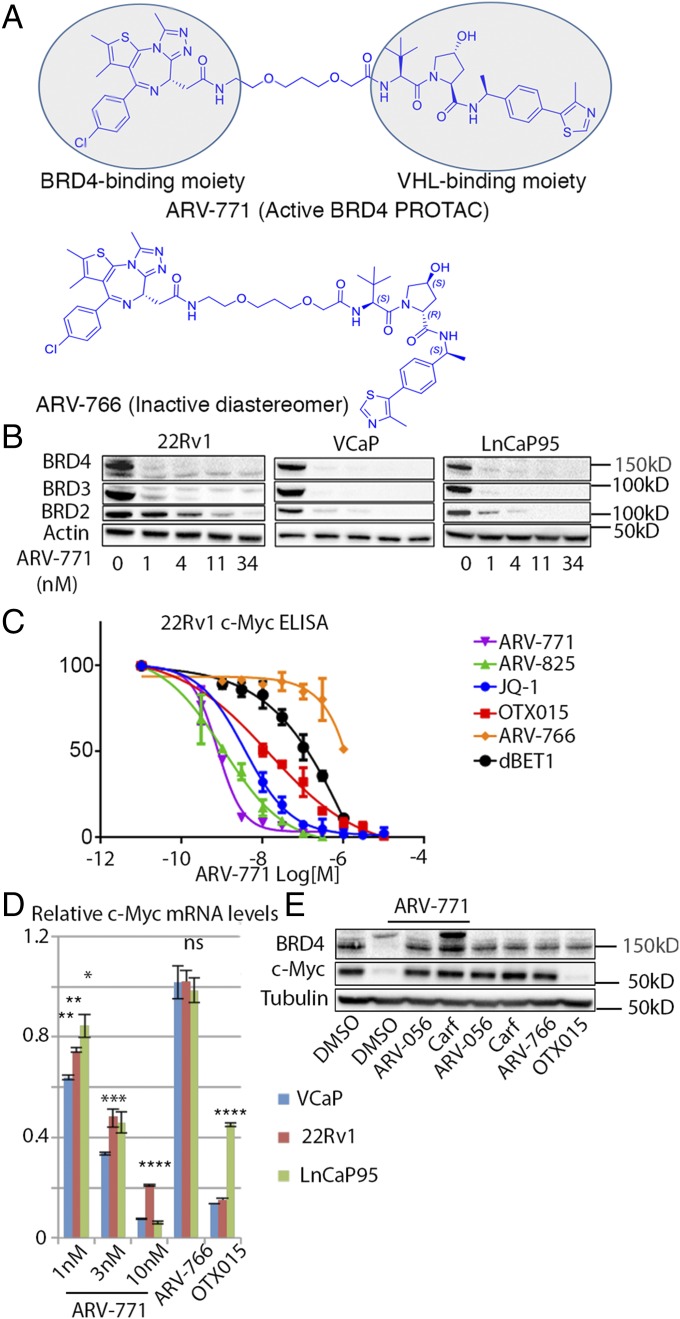

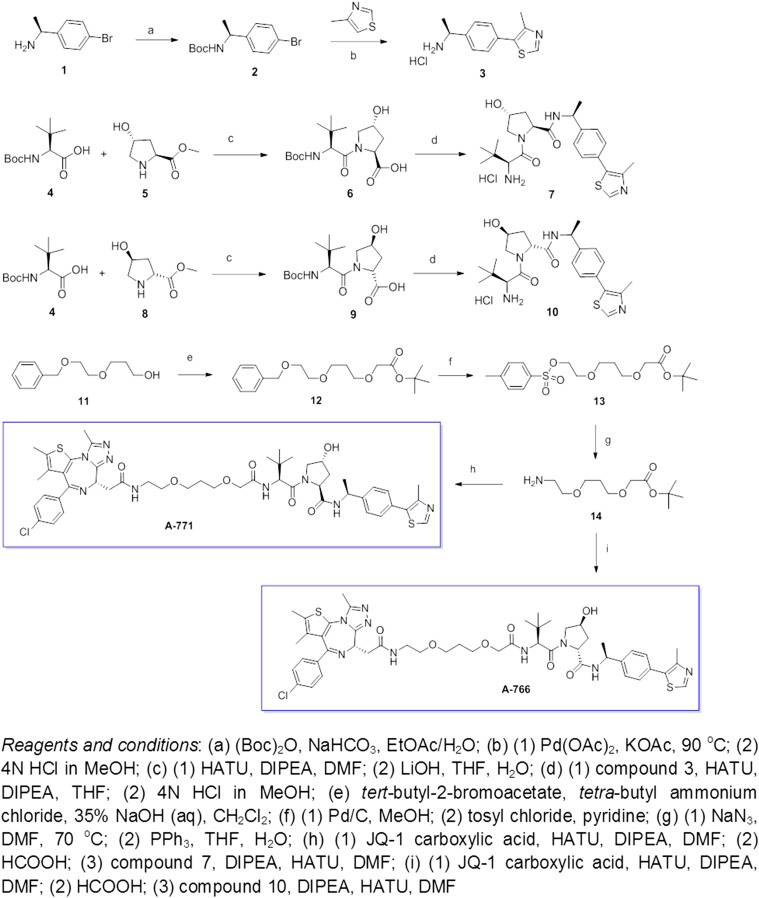

To meet our twin goals of developing a highly potent BET protein degrader that also possesses a pharmacokinetic (PK) profile favorable for in vivo testing, we used the triazolo-diazepine acetamide BET-binding moiety derived from BET inhibitors in clinical development (29). The BET-binding ligand was conjugated via a connecting linker to a recently described HIF-1α–derived (R)-hydroxyproline containing a VHL E3 ligase-binding ligand (30) to generate BET PROTACs. Lead molecules generated by varying linker length and composition were optimized for drug-like properties to obtain PROTACs suitable for in vivo studies. To this end, the BET PROTAC ARV-771 was developed. We also designed ARV-766, a diastereomer of ARV-771 with the opposite configuration at the hydroxyproline, which has no affinity for VHL, as a negative control for BET degradation (Fig. 1A). ARV-771 potently degrades BRD2/3/4 in 22Rv1 cells with a DC50 < 5 nM (Fig. 1B). We confirmed equally potent activity in the VCaP and LnCaP95 CRPC cell lines (Fig. 1B). Next, we ensured loss of BET function with ARV-771 by measuring levels of the c-MYC protein, a downstream effector of BET proteins. Indeed, treatment with ARV-771 resulted in depletion of c-MYC with an IC50 <1 nM (Fig. 1 C and D). In the same assay, the BET inhibitors JQ-1 and OTX015 were respectively approximately 10- and 100-fold less potent than ARV-771. Similarly, dBET1, a CRBN-based BET degrader reported in the literature, was ∼500-fold weaker than ARV-771. ARV-825 (23), a CRBN-based PROTAC with suboptimal PK, was as potent as ARV-771 in suppressing c-MYC. We determined the binding affinity of ARV-771 and the diastereomer ARV-766 for BET bromodomains to be comparable to that of Kd of JQ-1 as reported in the literature (31) (Fig. S2A). However, ARV-766 demonstrated only marginal suppression of c-MYC, suggesting that BET PROTACs have lower cellular permeability than JQ-1 and that the remarkable potency of ARV-771 is most likely caused by the “catalytic” nature of its cellular activity (26). The c-MYC suppression was indeed at the mRNA level, as determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 1D). Finally, we confirmed the VHL and proteasome dependence of ARV-771 activity by blocking it with an excess of the VHL ligand ARV-056 (Fig. S2B) or with the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, treatment with ARV-771 resulted in the appearance of a high-molecular-weight band in the BRD4 immunoblot, which is notably stronger in the presence of carfilzomib. Our efforts to characterize this band as ubiquitinated BRD4 proved inconclusive (Fig. S2C), and we hypothesize that it could represent a preproteolytic aggregated BRD4 species. The identity of the BRD4 bands was confirmed using RNAi (Fig. S2D).

Fig. 1.

ARV-771 is a potent pan-BET degrader. (A) Chemical structures of ARV-771 and the inactive diastereomer ARV-766, which is unable to bind VHL. (B) Incubation of the indicated CRPC cell lines with ARV-771 for 16 h results in depletion of BRD2/3/4 in 22Rv1, VCaP, and LnCaP95 cells. The Western blot is representative of three independent experiments (n = 3). (C) ARV-771 treatment for 16 h results in suppression of cellular c-MYC levels measured by ELISA. The assay was performed in triplicate (n = 3). (D) ARV-771–mediated c-MYC suppression occurs at the mRNA level, as determined by qPCR analysis following 16-h treatment at the indicated concentrations. c-MYC levels were also monitored in the same cell lines by qPCR following a 16-h treatment with either 1 μM ARV-766 or 1 μM OTX015. The results shown represent an average of two biological replicates, each measured in triplicate (n = 3). (E) ARV-771–mediated BRD4 degradation at 8 h is blocked by 30-min pretreatment with either an excess of VHL ligand ARV-056 (10 μM) or the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib (1 μM). The Western blot is representative of two independent experiments (n = 2). All data represent mean values ± SEM (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). P values were determined using GraphPad Prism using an unpaired parametric t test with Welch’s correction.

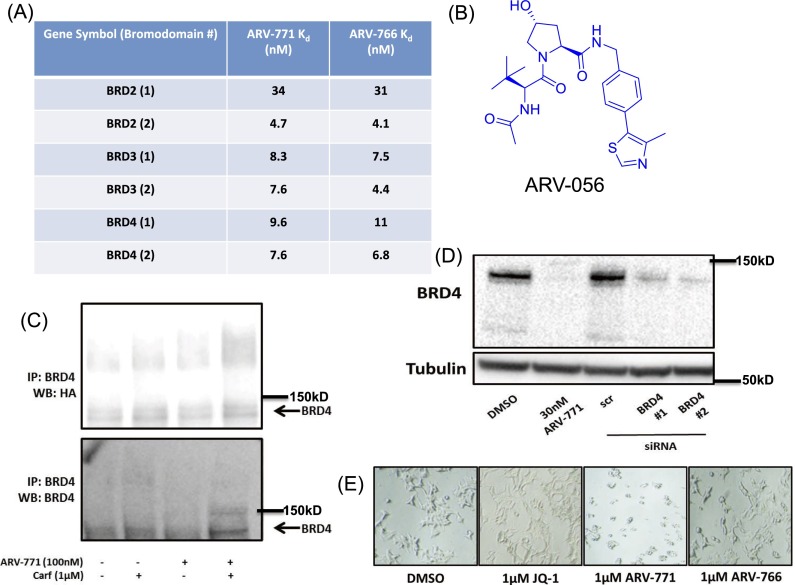

Fig. S2.

(A) Kd values of ARV-771 and ARV-766 against BRD1 and BRD2. (B) VHL ligand ARV-056. (C) BRD4 immunoprecipitated from 22Rv1 cells transfected with HA-Ubiquitin. (D) RNAi confirmation of BRD4 band identity in vitro. (E) ARV-771 treatment results in a change in 22Rv1 cellular morphology consistent with apoptosis. (Magnification: 20×.)

ARV-771 Treatment of CRPC Cells Results in Apoptosis.

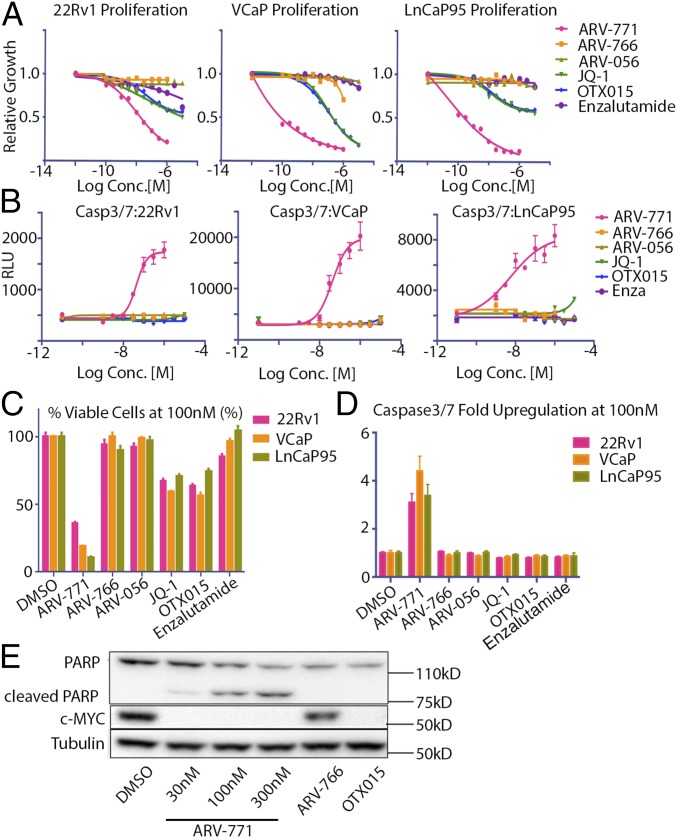

We next examined the effect of ARV-771 on cell proliferation. In the three cell lines tested (22Rv1, VCaP, and LnCaP95), ARV-771 was 10- to 500-fold more potent than JQ-1 or OTX015. Under our test conditions, both the diastereomer ARV-766 and enzalutamide had minimal effect on the proliferation of any of these cell lines, and the VHL ligand ARV-056 was completely inactive (Fig. 2 A and C). Notably, ARV-771 treatment had a pronounced effect on cell morphology consistent with apoptosis (Fig. S2E), which we corroborated by demonstrating that ARV-771 treatment was associated with significant caspase activation (Fig. 2 B and D). Finally, we confirmed the rapid induction of apoptosis with ARV-771 by demonstrating significant poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in 22Rv1 cells 16 h after PROTAC treatment (Fig. 2E). Under the same conditions, ARV-766 and the BET inhibitor OTX015 failed to induce any detectable PARP cleavage.

Fig. 2.

ARV-771 treatment results in cell death in CRPC cell lines. (A) Antiproliferative effect of ARV-771 in CRPC cell lines after 72-h treatment. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). (B) Treatment with ARV-771 for 24 h leads to caspase activation in CRPC cell lines. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). (C) Quantification of results in A. (D) Quantification of results in B. (E) A 24-h ARV-771 treatment leads to PARP cleavage in 22Rv1 cells. All data represent mean values ± SEM (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). P values were determined using GraphPad Prism using an unpaired t test with a false-discovery rate of 1%.

ARV-771 Suppresses FL-AR and AR-V7 Expression.

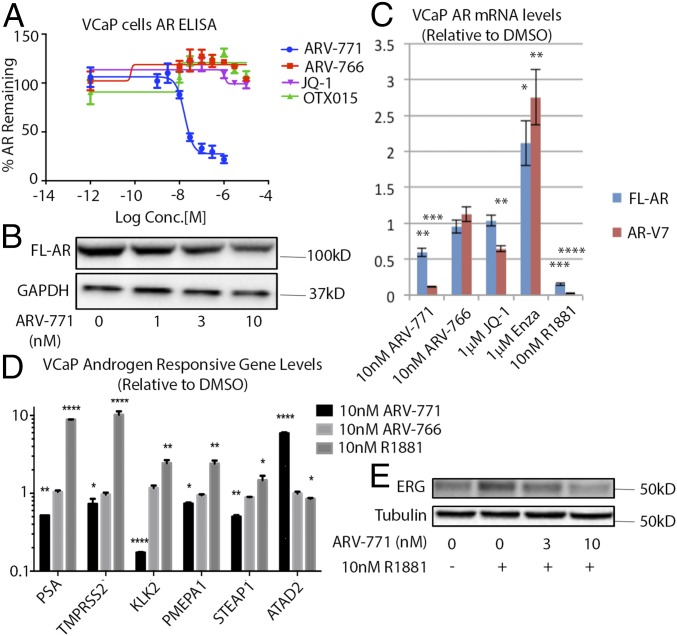

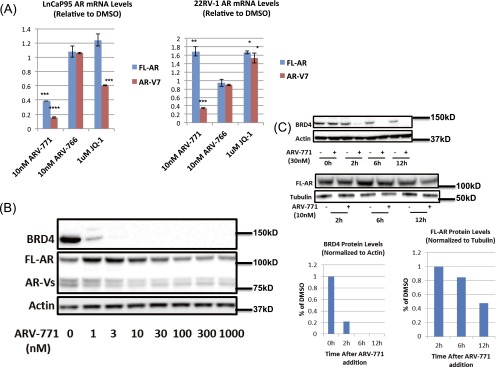

Although BET inhibitor activity against CRPC cells arises from mechanisms such as c-MYC suppression as well as from the inhibition of AR-driven transcription (19, 20), we hypothesized that BET depletion with ARV-771 may result in additional cellular effects. Interestingly, ARV-771, but not JQ-1 or OTX015, significantly lowered AR protein levels in VCaP cells as measured by ELISA (Fig. 3A) and immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). Although only FL-AR was detectable at the protein level in VCaP cells, expression of the mRNA encoding both FL-AR and the AR-V7 could be measured readily. AR-V7 is the best studied of the transcriptionally active AR splice variants detected in the clinic and has been hypothesized to play a role in acquired resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone (6, 11, 12, 32–34). We observed down-regulation of both FL-AR and AR-V7 mRNA upon treatment with 10 nM ARV-771 in VCaP cells (Fig. 3C). Although the BET inhibitor JQ-1 lowered AR-V7 levels in this assay, it had no effect on FL-AR. Similar results were obtained in LnCaP95 cells (Fig. S3A). In 22Rv1 cells, however, the levels of FL-AR showed more complex regulation in response to ARV-771, whereas AR-V7 levels were attenuated (Fig. S3B). As expected, ARV-766 showed no effect on either FL-AR or AR-V7 levels. The time course of AR down-regulation and BRD4 degradation also was established in VCaP cells. Interestingly, although the loss of BRD4 was complete by 6 h following ARV-771 treatment, levels of FL-AR took longer to attenuate (Fig. S3C). Treatment with the synthetic androgen R1881 down-regulated both transcripts, and enzalutamide had the opposite effect, as has been reported previously (35–37). Finally, we showed that ARV-771 has an antiandrogenic effect on a number of AR-regulated genes in VCaP cells (Fig. 3D). In addition, we carried out an RNA-sequencing experiment in 22Rv1 cells in which we analyzed changes in gene expression upon treatment with either 30 nM ARV-771 or 500 nM OTX015 (Datasets S1 and S2). Interestingly, although AR signaling was not identified by an unbiased bioinformatics analysis as one of the top five networks targeted by ARV-771 (Dataset S3), the levels of a number of AR-regulated genes (ELL2, PMEPA1, STEAP1, FAM105A, ATAD2, ENDOD1, and ZNF189) were found to be attenuated by >50% in this experiment. Similarly, immunoblotting for ERG, which also is regulated by AR in VCaP cells, revealed that the induction of this gene by the synthetic androgen R1881 could be blocked by ARV-771 pretreatment, providing further evidence that BET degradation with the PROTAC blocks AR signaling (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

ARV-771 treatment attenuates AR signaling. (A) ARV-771 treatment for 16 h results in lower FL-AR levels as measured by ELISA. The assay was performed in triplicate (n = 3). (B) ARV-771–mediated lowering of FL-AR levels demonstrated by immunoblotting after a 16-h treatment. The Western blot is representative of two independent experiments (n = 2). (C) mRNA levels of FL-AR and AR-V7 are lowered by a 16-h ARV-771 treatment in VCaP cells, as determined by qPCR analysis. The result shown is an average of two biological replicates, each measured in triplicate (n = 3). (D) Levels of androgen-responsive genes in response to a 16-h ARV-771 treatment. The result is an average of two biological replicates, each measured in triplicate (n = 3). (E) ERG induction by a 16-h treatment with R1881 in VCaP cells is blocked by a 1-h ARV-771 pretreatment. All data represent mean values ± SEM (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). P values were determined using GraphPad Prism using an unpaired parametric t test with Welch’s correction.

Fig. S3.

(A) FL-AR and AR-V7 mRNA levels in LnCaP95 and 22Rv1 cells. (B) AR protein levels in 22Rv1 cells in response to ARV-771. (C) Kinetics of depletion of BRD4 and FL-AR following ARV-771 treatment in VCaP cells. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

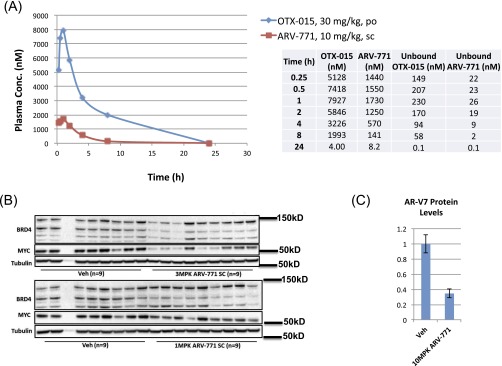

ARV-771 Induces Degradation in Vivo.

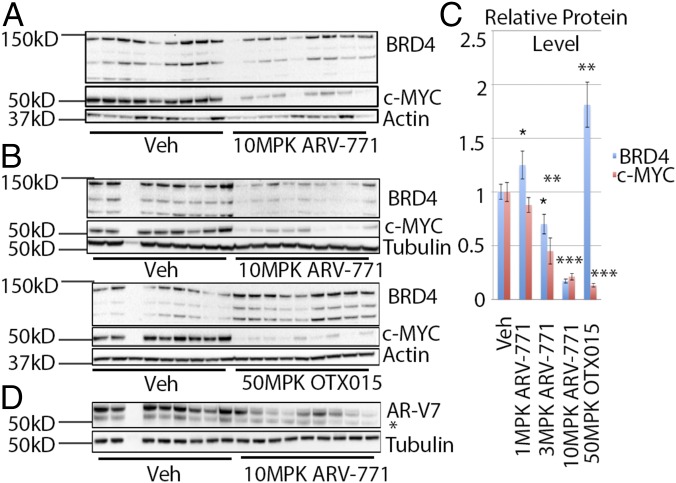

We next established that ARV-771 possesses physicochemical attributes that are favorable for in vivo experiments (Table S1). Consistent with these data, the PK profile of ARV-771 revealed that a single subcutaneous administration of a 10-mg/kg dose resulted in plasma drug levels significantly above the predicted efficacious concentration [c-MYC IC90 = 100 nM with 50% (vol/vol) mouse serum] (Table S1) for 8–12 h (Fig. S4A). Importantly, treatment of noncastrated male Nu/Nu mice bearing AR-V7+ 22Rv1 tumor xenografts with daily subcutaneous injections of ARV-771 at 10 mg/kg for 3 d resulted in 37% and 76% down-regulation of BRD4 and c-MYC levels, respectively, in tumor tissue (Fig. 4A). Separately, 2 wk of daily dosing resulted in a dose-dependent suppression of BRD4 and c-MYC in tumors with 10 mg/kg >80% knockdown of both at 8 h following the last 10-mg/kg dose. (Fig. 4 B and C and Fig. S4B). The corresponding 8-h ARV-771 plasma concentration of 1,200 ± 230 nM in these mice (Table S2) was significantly higher than its c-MYC IC90 in mouse serum, consistent with the robust BRD4 and c-MYC knockdown that was observed. Interestingly, administration of c-MYC 50 mg/kg OTX015 by oral gavage resulted in c-MYC down-regulation but also in an accumulation of BRD4 protein (Fig. 4 B and C). Finally, we also observed a marked down-regulation in levels of AR-V7 in the 22Rv1 tumors after ARV-771 treatment (Fig. 4D and Fig. S4C).

Table S1.

Physicochemical and PK (Pharmacokinetic) properties of ARV-771

| Properties | Value |

| MW/cPSA/clogD @ pH 7.4 | 985/208/2.55 Å2 |

| c-MYC IC90 with 50% mouse serum | 100 nM |

| Aqueous solubility in PBS | 17.8 µM |

| Permeability A to B/B to A in MDCK-MDR1 and PAMPA assay | 0.09/1.6110−6 cm/s (MDCK-MDR1), 1.49 10−6 cm/s (PAMPA) |

| Parent compound remaining after 60-min incubation with mice liver microsomes | 54.2% |

| Plasma protein binding, human/mouse | 93.1/98.5% bound |

| hERG IC50 | >30 µM |

| Mouse PK, i.v., 1 mg/kg | |

| CL | 24.0 mL/min/kg |

| AUC | 0.70 μM·h |

| Vss | 5.28 L/kg |

| Mouse PK, s.c. 10 mg/kg | |

| Cmax | 1.73 µM |

| Tmax | 1.0 h |

| AUC | 7.3 μM·h |

| F | 100% |

AUC, area under the curve; CL, clearance rate; clogD, calculated clogD value; Cmax, maximum concentration; cPSA, calculated polar surface area; F, oral bioavailability; i.v., intravenous; MW, molecular weight; PAMPA, parallel artificial membrane permeability assay; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; s.c., subcutaneous; Tmax, time to reach maximum concentration; Vss, steady state volume of distribution.

Fig. S4.

(A) PK profile of ARV-771 and OTX015 in mice after a single dose with the indicated route and concentration. (B) Down-regulation of BRD4 and MYC with 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg ARV-771 in a 14-d 22Rv1 tumor xenograft study. (C) Quantification of the Western blot in Fig. 4D.

Fig. 4.

ARV-771 is a potent in vivo PROTAC. (A) BRD4 down-regulation and c-MYC suppression in 22Rv1 tumor xenografts implanted in Nu/Nu mice after daily subcutaneous administration of 10 mg/kg ARV-771 for 3 d. Each treatment cohort contained nine animals (n = 9). (B) Effect of ARV-771 and OTX015 on BRD4 and c-MYC levels by immunoblotting in a 14-d 22Rv1 tumor xenograft study. Each treatment cohort contained nine animals (n = 9). (C) Quantification of results in B and Fig. S4B. Quantification of the highest BRD4 band in B is shown. Quantification of all three bands gave the same result. (D) AR-V7 levels in 22Rv1 tumor xenografts are also lowered by daily subcutaneous injection of 10 mg/kg ARV-771 in a 14-d 22Rv1 tumor xenograft study. All data represent mean values ± SEM. In all experiments, tumors and plasma were harvested 8 h after the last dose for analysis (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). P values were determined using GraphPad Prism using an unpaired parametric t test with Welch’s correction.

Table S2.

Plasma concentrations of ARV-771 in mice treated subcutaneously once daily with 10 mg/kg ARV-771

| Animal no. | ARV-771 concentration (nM) |

| 1 | 1,250 |

| 2 | 2,260 |

| 3 | 924 |

| 4 | 355 |

| 5 | 355 |

| 6 | 1,770 |

| 7 | 1,070 |

| 8 | 2,380 |

| 9 | 1,010 |

| 10 | 615 |

Mean, 1,200 nM; SEM, 230 nm.

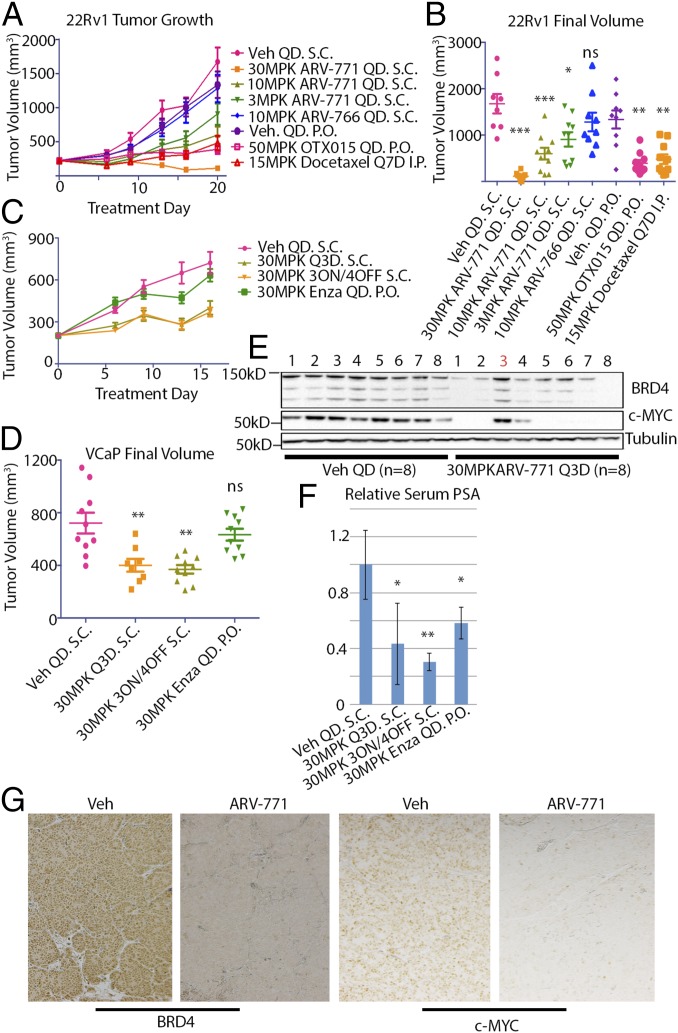

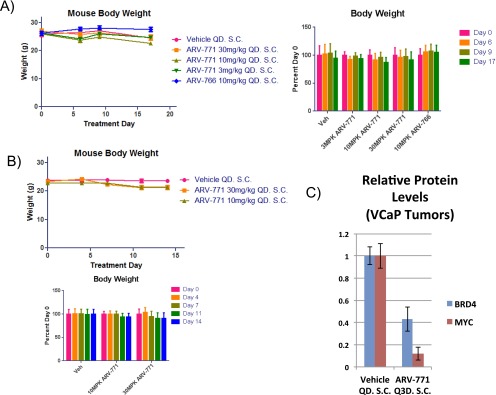

ARV-771 Induces Regression in 22Rv1 Tumor Xenografts.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that BET degradation with ARV-771 should result in improved efficacy as compared with BET inhibition in the context of an animal model of CRPC. For this purpose, we first examined the 22Rv1 tumor xenograft model, in which the BET inhibitor OTX015 has been reported to result in TGI (21). Daily subcutaneous administration of ARV-771 in noncastrated male Nu/Nu mice bearing 22Rv1 tumors resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in average tumor size as compared with vehicle administration (Fig. 5 A and B). Strikingly, the 30-mg/kg dose of ARV-771 induced tumor regression, with 2 of 10 mice being devoid of any palpable tumor mass after treatment. No significant difference in tumor size was seen with treatment with the diastereomer ARV-766 as compared with vehicle control, validating the applicability of the PROTAC mechanism in vivo. Interestingly, OTX015 resulted in 80% TGI in our hands, outperforming the reported results (21) but still representing progressive disease. The TGI achieved with OTX015 probably can be explained by its PK profile, which reveals much higher plasma concentrations of the molecule than of ARV-771 (Fig. S4A). Docetaxel treatment, representing the current chemotherapeutic approach in drug-resistant metastatic CRPC, resulted in TGI similar to that achieved with OTX015, proving that BET degradation represents an improvement over the current clinical treatment regimen in cases of enzalutamide- or abiraterone-resistant PCa. Crucially, no treatment resulted in a significant loss in body weight, providing evidence that the observed tumor shrinkage was not a product of systemic in vivo toxicity (Fig. S5A). Interestingly, we did observe noticeable skin discoloration, suggesting an overall deterioration of skin health, originating at the injection site in the mice receiving chronic ARV-771 dosing but not in those receiving the inactive epimer ARV-766. BRD4 depletion in the skin recently has been shown to result in epithelial hyperplasia, along with follicular dysplasia and subsequent alopecia (38). However, these severe effects have been shown to be rapidly reversible, and in our experiments the appearance of the skin returned to normal after a 2- to 3-d dosing holiday.

Fig. 5.

ARV-771 is efficacious in multiple tumor xenograft models of CRPC. (A) Results of an efficacy study in 22Rv1 tumor xenografts implanted in Nu/Nu mice showing tumor regression with 30 mg/kg subcutaneously once daily ARV-771 dosing. Each treatment cohort contained 10 animals (n = 10). (B) Scatter plot of the results from A demonstrating dose-dependent TGI with ARV-771. (C) Intermittent dosing schedules of ARV-771 are sufficient to induce TGI in CB17 SCID mice bearing VCaP tumor xenografts. Each treatment cohort contained 10 animals (n = 10). (D) Scatter plot of the results from C. (E) ARV-771 dosing results in pharmacodynamic depletion of BRD4 and suppression of c-MYC in the VCaP tumor xenograft model. (F) PSA levels in serum from the mice in C were analyzed by ELISA, showing suppression of levels with ARV-771 treatment. The numbers of replicates for treatments shown in the graph were 8, 5, 8, and 8, respectively. (G) Immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples from vehicle- and ARV-771–treated VCaP tumor-bearing mice. All data represent mean values ± SEM. In all experiments, tumors and plasma were harvested 8 h after the last dose (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). P values were determined using GraphPad Prism using an unpaired parametric t test with Welch’s correction.

Fig. S5.

(A) Body weights of mice in the 22Rv1 xenograft study. (B) Body weights of mice in the VCaP xenograft study. (C) Quantification of immunoblots in Fig. 5E.

Next, we confirmed that ARV-771 efficacy in 22Rv1 tumor xenografts was not an artifact of cellular lineage. Specifically, we chose the VCaP tumor model, which represents the clinical setting of AR overexpression following androgen-deprivation therapy. Because the CB17 SCID mice bearing VCaP xenografts did not tolerate daily dosing of either ARV-771 or OTX015, we explored intermittent dosing in this experiment. Noncastrated male CB17 SCID mice bearing VCaP tumor xenografts were treated with two intermittent dosing schedules of ARV-771, every 3 d (Q3D) or 3 d on/4 d off, for a total of 16 d, during which the vehicle arm underwent a quadrupling of tumor size (Fig. 5 C and D). Both dosing schedules resulted in an identical 60% TGI over this time course without significant loss in body weight in either arm (Fig. S5B). In comparison, enzalutamide had a marginal impact on tumor growth. Although we observed no alopecia with ARV-771 dosing in the CB17 SCID mice, the lack of tolerance for daily dosing does suggest potentially significant toxic effects. With chronic intermittent dosing in our experiment, toxicity presented primarily as hunching of the spine, along with lethargy and decreased mobility in PROTAC-treated mice.

BRD4 levels in tumor samples from the Q3D arm were found to be down-regulated by an average of 57% compared with vehicle, with an 88% drop in corresponding c-MYC levels (Fig. 5E and Fig. S5C). Plasma PK analysis of the Q3D arm revealed that the lack of BRD4 and c-MYC suppression in animal no. 3 (Fig. 5E) was explained by the corresponding low levels of the drug in circulation (Table S3), further consolidating the PK/pharmacodynamic relationship with ARV-771. Crucially, ARV-771 lowered circulating PSA, a surrogate for PCa tumor burden in the clinic, by 60% or 80% by ELISA, depending on the dosing schedule (Fig. 5F). Surprisingly, although enzalutamide had little impact on tumor growth, it resulted in a 40% reduction in PSA serum levels. Finally, we confirmed our findings of BRD4 and c-MYC suppression with immunohistochemical analysis of tumor samples collected from the vehicle and ARV-771 Q3D cohorts (Fig. 5G).

Table S3.

Plasma concentrations of ARV-771 in mice treated s.c. with 10 mg/kg ARV-771 Q3D

| Animal no. | ARV-771 concentration (nM) |

| 1 | 2,210 |

| 2 | 2,040 |

| 3 | 95.8 |

| 4 | 380 |

| 5 | 2,070 |

| 6 | 2,790 |

| 7 | 951 |

| 8 | 798 |

Mean, 1,400 nM; SEM, 350 nm.

Discussion

Despite recent advances in antiandrogen therapy, 20–40% of patients with metastatic CRPC demonstrate de novo resistance to the newly FDA-approved drugs abiraterone and enzalutamide, and the remaining patients acquire resistance during treatment (8–11). Several BET inhibitors have recently shown promising efficacy in preclinical models of CRPC (19–21). Although the specific mechanisms behind this activity are a subject of intense scrutiny, BET inhibitors are thought to function partly by blocking BRD4 localization to AR target loci, thereby inhibiting AR-mediated transcription (20), and partly by abrogating c-MYC transcription (19).

PROTACs, which are chimeric bifunctional small molecules that recruit an E3 ligase to force the destruction of a target protein of interest, have been developed by us and others as BET protein-targeting agents (23–25). Until now, none of these BET PROTACs has been reported to have in vivo activity in a solid-tumor malignancy. Moreover, the physicochemical properties of the first-generation BET PROTAC shown to be efficacious in a mouse model of AML necessitated intraperitoneal delivery, which usually is not a clinically relevant route of administration. Here we have described a VHL-based BET targeting PROTAC, ARV-771, which shows <5 nM potency of BRD2/3/4 degradation in several prostate cancer cell lines. ARV-771 also has an antiproliferative effect that is up to 500-fold more potent than the BET inhibitors JQ-1 and OTX015 in these cell lines. Although we believe that ARV-771 and BET inhibitors share some common mechanism(s) of action, we hypothesize that protein depletion with a PROTAC could result in pleiotropic outcomes that would not be accessible with traditional inhibitors. Interestingly, it recently has been discovered that one of the mechanisms of acquired resistance to BET inhibitors in breast cancer involves completely BRD-independent transcriptional regulation mediated by BRD4 (39). Similarly, in the same study, BRD4 knockdown by shRNA was shown to have much more significant antitumor effects than mere small-molecule inhibition. A separate study reported increased sensitivity of breast cancer lines to BRD4 siRNA compared with BET inhibition (40). Given these emerging data, and because BET family proteins are known to have scaffolding functions whereby they interact with a variety of transcriptional regulators through their extraterminal and C-terminal domains (41, 42), we hypothesized that a BET degrader would have a more profound effect than a BET inhibitor on the growth and/or survival of prostate tumor cells. Our observation that ARV-771 lowers levels of FL-AR in addition to AR-V7 in VCaP cells, whereas BET inhibitors impact only the latter, supports this hypothesis. These data are consistent with other reports that show no impact of BET inhibitors on FL-AR levels (19, 20), although one recent study claims that BET inhibitors do decrease FL-AR levels (22). Accumulating evidence in the literature suggests that AR splice variants may mediate castration resistance, in part by heterodimerization with FL-AR and activation of the latter in an androgen-independent manner (15, 16, 37). Although the attenuation of AR transcript variant levels is likely only one among many antiproliferative mechanisms downstream of the depletion of important epigenetic regulators such as BRD2/3/4, it nonetheless is of considerable importance in the context of PCa. The superiority of a BET PROTAC compared with a BET inhibitor is demonstrated by the observations that ARV-771 induces apoptosis in CRPC cells grown in vitro, whereas JQ-1 and OTX015 have only a cytostatic effect in the same time frame. Furthermore, ARV-771 induces regression of 22Rv1 xenografts compared with the 80% TGI that occurs in mice treated with OTX015. This effect clearly establishes the value of BET degraders over inhibitors, which, although efficacious in vivo, still result in progressive disease. Taken together, our results strongly support pursuing PROTAC-mediated BET degradation as a therapeutic strategy in CRPC.

Materials and Methods

All experiments described in this paper were approved by the Arvinas Senior Management Team. All human-derived materials used in this study were obtained from commercial vendors and did not require informed consent. For full methods, see SI Materials and Methods.

Reagents.

The 22Rv1 and VCaP cell lines were purchased from ATCC. LnCap95 cells were a generous gift from Alan Meeker at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. BRD2 (5848), BRD4 (13440), PARP (9532), and c-MYC (5605) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. BRD3 (sc-81202) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were c-MYC (ab32072, Abcam) and BRD4 (a301-985a50, Bethyl Laboratories). Actin and tubulin antibodies were purchased from Sigma.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (catalog no. 89900, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with protease inhibitors (EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Tablets, catalog no. 88266, Pierce). Lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g, and the supernatants were used for SDS/PAGE. Western blotting was carried out following standard protocols.

RT-qPCR.

Cells were treated as indicated and were pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 2 min, followed by washing with PBS. Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit (catalog no. 74104), and cDNA was generated using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (catalog no. 4368814, Thermo Fisher). qPCR was performed using the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time Thermocycler. The primer sets used for RT-PCR are listed in Table S4.

Table S4.

qPCR primer sequences

| Gene | Primers |

| c-MYC | GGC TCC TGG CAA AAG GTC A |

| CTG CGT AGT TGT GCT GAT GT | |

| PSA/KLK3 | CAC AGG CCA GGT ATT TCA GGT |

| GAG GCT CAT ATC GTA GAG CGG | |

| FL-AR | GACGACCAGATGGCTGTCATT |

| GGGCGAAGTAGAGCATCCT | |

| AR-V7 | CAGGGATGACTCTGGGAGAA |

| GCCCTCTAGAGCCCTCATTT | |

| TMPRSS2 | CAA GTG CTC CAA CTC TGG GAT |

| AAC ACA CCG ATT CTC GTC CTC | |

| KLK2 | TCA GAG CCT GCC AAG ATC AC |

| CAC AAG TGT CTT TAC CAC CTG T | |

| PMEPA1 | TGT CAG GCA ACG GAA TCC C |

| CAG GTA CGG ATA GGT GGG C | |

| STEAP1 | CCC TTC TAC TGG GCA CAA TAC A |

| GCA TGG CAG GAA TAG TAT GCT T | |

| ATAD2 | GGA AAA ACC TCG TCA CCA GAG |

| CGC CTG TTC ATT CGT TTA CAG TA | |

| HPRT | CCT GGC GTC GTG ATT AGT GAT |

| AGA CGT TCA GTC CTG TCC ATA A |

Immunohistochemistry.

Tumor tissue was dissected, fixed in 10% (vol/vol) formalin (HT501128-4L, Sigma), and embedded in paraffin (catalog no. MER HWW, Mercedes Medical). Tumor sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in an ethanol series. Slides then were permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100 (in PBS) for 10 min; antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH = 6) at 100 °C for 10 min and then was blocked with Avidin-Biotin Reagents (SP-2001, Vector Laboratories), followed by 10% (vol/vol) horse serum block. Slides then were incubated with either anti-c-MYC (rabbit monoclonal, ab32072, Abcam) or anti-BRD4 (a301-985a50, Bethyl Laboratories) at a 1:1,000 dilution overnight at 4 °C. On the next day, after washing with PBS, slides were blocked with 3% (vol/vol) H2O2 (in PBS), followed by incubation with biotinylated horse anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 30 min. Peroxidase ABC Substrate (PK-6100, Vector Laboratories) was applied for 30 min, and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (SK-4100, Vector Laboratories) was used for color development. Nuclei were counterstained with Gill III hematoxylin and lithium carbonate.

c-MYC ELISA.

22Rv1 cells (30,000 cells per well) were dosed with compounds serially diluted at 1:3 ratio for an eight-point dose curve. The medium was aspirated, and cells were washed once with PBS. RIPA buffer (50 μL) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors was used to lyse cells. Lysates were centrifuged and transferred to a 96-well c-MYC ELISA plate (catalog no. KH02041, Novex, Life Technologies).

AR ELISA.

VCaP cells (40,000 cells per well) were dosed with compounds serially diluted at 1:3 ratio for an eight-point dose curve. Medium was aspirated, and cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (9803, Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged and transferred to a 96-well Androgen Receptor ELISA plate (PathScan Total Androgen Receptor Sandwich ELISA Kit 12850, Cell Signaling Technology).

Cell Proliferation Assay Protocol.

22Rv1 cells (5,000 cells per well) were dosed with compounds serially diluted 1:3 for a 10-point dose curve for 72 h. CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (G7573, Promega) was added, and the plate was read on a luminometer. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Apoptosis Assay Protocol.

22Rv1 cells (5,000 cells per well) were dosed with compounds serially diluted 1:3 for a 10-point dose curve for 48 h. Caspase-Glo 3/7 (Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay G8093, Promega) was added, and the plate was read on a luminometer. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

RNA Sequencing.

22Rv1 cells were treated with DMSO, 30 nM ARV-771, or 500 nM OTX015 for 6 h, trypsinized, and pelleted. Total RNA was extracted using the QIAGEN RNeasy kit. RNA samples were sequenced, and the bioinformatics analysis was performed at the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Microarray Core, using twofold gene up- or down-regulation as an arbitrary cut-off.

Animal Studies.

All experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the New England Life Sciences Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and were implanted subcutaneously with 5 × 106 22Rv1 or VCaP cells in Matrigel (Corning Life Sciences). Dosing was carried out for up to 3 wk, depending on the experiment. Mice were sacrificed 8 h after the final dose. Plasma and tissues were harvested and flash frozen for further analysis. All PK analysis was carried out at Drumetix Laboratories. Plasma PSA was analyzed by the PathScan Total PSA/KLK3 Sandwich ELISA Kit (14119, Cell Signaling Technology) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Chemical Synthesis.

Detailed procedures for the synthesis of ARV-771 and ARV-766 are provided in SI Materials and Methods. For the synthetic scheme, see Fig. S6.

Fig. S6.

Synthetic scheme for ARV-771 and ARV-766.

SI Materials and Methods

Reagents.

22Rv1 and VCaP cell lines were purchased from ATCC. LnCap95 cells were a generous gift from Alan Meeker at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. 22Rv1 and VCaP cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. LnCaP95 cells were cultured in Phenol Red-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Media and serum were purchased from Invitrogen. BRD2 (5848), BRD4 (13440), PARP (9532), c-MYC (5605) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. BRD3 (sc-81202) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were c-MYC (ab32072, Abcam) and BRD4 (a301-985a50, Bethyl Laboratories). Actin and tubulin antibodies were purchased from Sigma.

Human c-MYC ELISA Assay Protocol.

22Rv1 cells were seeded at 30,000 cells per well at a volume of 75 μL per well in RPMI + 10% (vol/vol) FBS medium in 96-well plates and were grown overnight at 37 °C. Cells were dosed with compounds at a 4× concentration diluted in 0.4% DMSO; compounds were serially diluted 1:3 for an eight-point dose curve. Twenty-five microliters of compounds were added to cells for a final concentration starting at 300 nM:0.3 nM in 0.1% DMSO and were incubated for 18 h. The medium was aspirated, and cells were washed once with PBS and aspirated. Cells were lysed in 50 μL RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Tx-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate] supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Plates were incubated on ice for 15 min and then were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 2,300 × g. Fifty microliters of cleared lysate from a 96-well assay plate were placed in a 96-well c-MYC ELISA plate (catalog no. KH02041, Novex, Life Technologies). Standard c-MYC was reconstituted with standard diluent buffer; the standard curve range is 333–0 pg/mL, diluted 1:2 for an eight-point dose curve. The rest of the assay was performed following the protocol from the c-MYC ELISA kit. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

AR ELISA.

VCaP cells were seeded at 40,000 cells per well at a volume of 100 μL per well in RPMI + 5% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped serum medium in 96-well plates and were grown for 2 d at 37 °C. Cells were dosed with compounds at a 100× concentration diluted in 1% DMSO; compounds were serially diluted 1:3 for an eight-point dose curve. One microliter of compound was added to cells for a final concentration starting at 10 μM or 1 μM in 0.01% DMSO and was incubated for 18 h. Medium was aspirated, and cells were lysed in 100 μL cell lysis buffer (9803, Cell Signaling Technology) [20 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM disodium EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 μg/mL leupeptin] supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Plates were incubated on ice for 10 min and then were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 2,300 × g. Five microliters of cleared lysate from a 96-well assay plate was added to a 96-well Androgen Receptor ELISA plate (PathScan Total Androgen Receptor Sandwich ELISA Kit 12850, Cell Signaling Technology) containing 100 μL of sample diluent. The rest of the assay was performed following the protocol from the Androgen Receptor ELISA kit. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Cell Proliferation Assay Protocol.

22Rv1 cells were seeded at 5,000 cells per well at a volume of 75 μL per well in RPMI + 10% (vol/vol) FBS medium in 96-well plates and were grown overnight at 37 °C. Cells were dosed with compounds at a 4× concentration diluted in 0.4% DMSO; compounds were serially diluted 1:3 for a 10-point dose curve. Twenty-five microliters of compounds were added to cells for a final concentration starting at 300 nM:0.3 nM in 0.1% DMSO and were incubated for 72 h. In a separate plate, 100 μL of 5,000 cells per well were plated in eight wells. Then 100 μL of CellTiter-Glo (CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay G7573, Promega) was added, incubated for 30 min, and then was read on a luminometer to assess the initial signal for cell growth. After 72 h, 100 μL of CellTiter-Glo was added, incubated for 30 min, and read on a luminometer. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Apoptosis Assay Protocol.

22Rv1 cells were seeded at 5,000 cells per well at a volume of 75 μL per well in RPMI + 10% (vol/vol) FBS medium in 96-well plates and were grown overnight at 37 °C. Cells were dosed with compounds at a 4× concentration diluted in 0.4% DMSO; compounds were serially diluted 1:3 for an eight-point dose curve. Twenty-five microliters of compounds were added to cells for a final concentration starting at 300 nM:0.3 nM in 0.1% DMSO and were incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, 100 μL of Caspase-Glo 3/7 (Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay G8093, Promega) was added, incubated for 30 min, and read on a luminometer. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Animal Studies.

Mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facilities at New England Life Sciences. All experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the New England Life Sciences Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Nu/Nu mice and CB17 SCID mice were obtained at age 4–5 wk from Charles River Laboratories and were implanted subcutaneously with 5 × 106 22Rv1 cells or 5 × 106 VCaP cells in Matrigel (Corning Life Sciences). After 10–14 d, mice bearing tumors >200 mm3 were randomized into the indicated number of groups with 10 mice in each group, ensuring that mean tumor volumes (±5 mm3) were identical in each group. Dosing was carried out through the indicated route and with the indicated schedule for each drug for up to 3 wk, depending on the experiment. Mice were killed 8 h after the final dose. Blood was collected, processed to plasma, and flash frozen for PK analysis. Tissues were harvested and flash frozen for further analysis. All PK analysis was carried out at Drumetix Laboratories. Two of the 10 animals in each study arm were randomly excluded in pharmacodynamic analyses for greater technical ease of running a 20-well protein gel. For PSA ELISA, only samples with at least 25 μL of plasma remaining after PK analysis were used using the PathScan Total PSA/KLK3 Sandwich ELISA Kit (14119, Cell Signaling Technology) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Procedures for the Synthesis of ARV-771 and ARV-766.

Preparation of (S)-tert-butyl -1-(4-bromophenyl)-ethyl carbamate (compound 2).

To a mixture of (S)-1-(4-bromophenyl)ethanamine (3.98 g, 19.9 mmol) and NaHCO3 (1.24 g, 14.8 mmol) in water (10 mL) and ethyl acetate (10 mL), (Boc)2O (5.20 g, 23.8 mmol) at 5 °C was added. The reaction continued for 2 h. TLC showed the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was filtered. The solid fraction was collected and suspended in a mixture of hexane (10 mL) and water (10 mL) for 0.5 h. The mixture was filtered, and the solid fraction was collected and dried in an oven at 50 °C to afford the title compound as a white solid (5.9 g, 98.7%). 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.28 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.36 (s, 9H), 4.55–4.60 (m, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (br, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H).

Preparation of (S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethanamine hydrochloride (compound 3).

A mixture of compound 2 (4.0 g, 13.3 mmol), 4-methylthiazole (2.64 g, 26.6 mmol), palladium (II) acetate (29.6 mg, 0.13 mmol), and potassium acetate (2.61 g, 26.6 mmol) in N,N-dimethylacetamide (10 mL) was stirred at 90 °C under nitrogen for 18 h. After cooling to ambient temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered. Fifty milliliters of water was added to the filtrate, and the resulting mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 4 h. The reaction mixture was filtered. The solid was collected by filtration and dried in an oven at 50 °C to afford (S)-tert-butyl 1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl carbamate (3.48 g, 82.3%) as a gray solid. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.33 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.38 (s, 9H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 4.64–4.68 (m, 1H), 7.23 (br d, 0.5H), 7.39 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (br d, 0.5H), 8.99 (s, 1H); LC-MS [M+1]+: 319.5.

This solid material (1.9 g, 6.0 mmol) was dissolved in 4N HCI in methanol (5 mL, 20 mmol, prepared from acetyl chloride and methanol), and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 3 h. The mixture was filtered, and the solid was collected and dried in an oven at 60 °C to afford (S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethanamine hydrochloride (1.3 g, 85%) as a light green solid. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.56 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 2.48 (s, 3H), 4.41–4.47 (m, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.4Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.75 (s, 3H), 9.17 (s, 1H); LC-MS [M+1]+: 219.2.

Preparation of (2S, 4R)-1-{(S)-2-[(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl}-4-hydroxypyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid (compound 6).

HATU (2.15 g, 5.7 mmol; Aldrich) was added to a solution of (S)-2-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoic acid (1.25 g, 5.4 mol), (2S,4R)-methyl 4-hydroxypyrrolidine-2-carboxylate hydrochloride (0.98 g, 5.4 mmol), and DIPEA (2.43 g, 18.9 mmol; Aldrich) in dimethylformamide (10 mL) at 0 °C under nitrogen. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 18 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (30 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (15 mL × 4). The combined organic layer was washed twice with 5% (vol/vol) citric acid (10 mL), twice with saturated NaHCO3 solution (10 mL), and twice with brine (10 mL) and was dried over Na2SO4. The organic solution was filtered and concentrated to afford (2S, 4R)-methyl 1-{(S)-2-[(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl}-4-hydroxypyrrolidine-2-carboxylate as a pale yellow oil (1.93 g, 100% yield). This crude product (1.93 g) and lithium hydroxide hydrate (2.2 g, 54 mmol) were taken into tetrahydrofuran (THF) (20 mL) and water (10 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 18 h. THF was removed by concentration. The residue was diluted with ice water (10 mL) and the pH was slowly adjusted to 2–3 with 3N HCI. The resulting suspension was filtered and washed with water (6 mL × 2). The solid was collected by filtration and was dried in an oven at 50 °C to afford the title compound as a white solid (1.4 g, 75% for two steps). 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 6.50 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 5.19 (br s, 1H), 4.32 (br s, 1H), 4.25 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 3.57–3.66 (m, 2H), 2.08–2.13 (m, 1H), 1.85–1.91 (m, 1H), 1.38 (s, 9H), 0.94 (s, 9H).

Preparation of (2S,4R)-1-[(S)-2-amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl]-4-hydroxy-N-[(S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl]-pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (compound 7).

HATU (1.6 g, 4.2 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of compound 6 (1.21 g, 3.5 mmol), compound 3 (0.9 g, 3.5 mmol), and DIPEA (1.36 g, 10.5 mmol) in anhydrous THF (15 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting mixture was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and was stirred for 2 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. THF was removed by concentration. Water (15 mL) was added to the residue, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 4 h and then was filtered. The solid was collected and dried in an oven at 50 °C to give a white solid. This solid was suspended in methanol (10 mL), and activated carbon (150 mg) was added. The resulting mixture was heated to 80 °C and was stirred for 1 h. The mixture was filtered while it was hot. Water (5 mL) was added to the filtrate at 80 °C. The resulting mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, and stirring continued for 18 h. The suspension was filtered. The solid was collected and dried in an oven at 50 °C to afford tert-butyl-{(S)-1-[(2S,4R)-4-hydroxy]-2-[ (S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethylcarbamoyl]pyrrolidin-1-yl}-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl-carbamate (1.41 g, 74.2%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.05 (s, 9H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.47 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 2.04–2.10 (m, 1H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.58–2.64 (m, 1H), 3.23 (s, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 11.2 Hz, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (br, 1H), 4.79 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.04–5.11 (m, 1H), 5.22 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.42 (m, 4H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.6 Hz 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H). This solid (1.04 g, 1.9 mmol) was dissolved in 4N HCI in methanol (3.0 mL), and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 3 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was concentrated to remove all volatiles under reduced pressure to give a light yellow solid. The solid was added to tert-butyl methyl ether (5 mL), and the resulting mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 4 h. The reaction mixture was filtered, and the solid was collected and dried in an oven at 50 °C to afford compound 7 (0.92 g, 100%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.03 (s, 9H), 1.38 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.72–1.79 (m, 1H), 2.09–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 3.48–3.52 (m, 1H), 3.75–3.79 (m, 1H), 3.88–3.90 (m, 1H), 4.31 (br, 1H), 4.56 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.89–4.95 (m, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 8.20 (br, 3H), 8.67 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 9.22 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 170.7, 167.1, 153.0, 146.5, 145.7, 132.5, 129.4, 129.3, 126.9, 69.4, 59.3, 58.5, 56.9, 48.3, 38.4, 34.8, 26.6, 23.0, 15.7; LC-MS [M+1]+: 445.6.

Preparation of (2R,4S)-1-[(S)-2-amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl]-4-hydroxy-N-[(S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl]-pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (compound 10).

Compound 10 was synthesized using the method described for the preparation of compound 7 using (2R,4S)-methyl 4-hydroxypyrrolidine-2-carboxylate hydrochloride. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 1.14 (s, 9H), 1.55 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 2.00–2.05 (m, 1H), 2.51–2.58 (m, 1H), 2.65 (s, 3H), 3.77–3.81 (m, 1H), 3.88–3.92 (m, 1H), 4.06 (br, 1H), 4.41–4.46 (m, 1H), 4.56–4.60 (m, 1H), 5.07–5.12 (m, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 10.02 (s, 1H). LC-MS [M+H]+: 445.3.

Preparation of tert-butyl 2-(3-(2-(benzyloxy)ethoxy)propoxy)acetate (compound 12).

A mixture of 3-(2-(benzyloxy)ethoxy)propan-1-ol (6.7 g, 31.86 mmol, prepared from 2-benzyloxyethanol and allyl bromide in two steps of ether formation and hydroboration), tert-butyl 2-bromoacetate (12.4 g, 63.73 mmol), tetra-butyl ammonium chloride (8.9 g, 31.86 mmol), and 35% (vol/vol) sodium hydroxide aqueous solution (35 mL) in dichloromethane (35 mL) was stirred at room temperature overnight. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The mixture was partitioned between methylene chloride (100 mL) and water (100 mL). The organic layer was collected, washed with brine (100 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a residue that was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography [eluted with 10–20% (vol/vol) ethyl acetate in hexane] to afford compound 12 (4.1 g, yield 40%) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.47 (s, 9H), 1.88–1.95 (m, 2H), 3.57–3.63 (m, 8H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 7.27–7.35 (m, 5H).

Preparation of tert‐butyl 2‐(3‐{2‐[(4-methylbenzenesulfonyl)oxy]ethoxy}propoxy)acetate (compound 13).

A mixture of tert‐butyl 2‐{3‐[2‐(benzyloxy)ethoxy]propoxy}acetate (4.1 g, 12.64 mmol) and palladium on carbon [10% (wt/vol), 160 mg] in methanol (30 mL) was stirred at 40 °C overnight under hydrogen atmosphere (hydrogen balloon). TLC showed that the reaction was complete. Palladium on carbon was removed through filtration and washed twice with methanol (20 mL). The combined filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford tert-butyl 2-[3-(2-hydroxyethoxy)propoxy]acetate (2.81 g, crude) as a colorless oil that was used in the next step without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.48 (s, 9H), 1.87–1.93 (m, 2H), 2.36 (br, 1H), 3.56–3.58 (m, 2H), 3.60–3.64 (m, 4H), 3.72–3.74 (m, 2H), 3.96 (s, 2H). This oily material (2.81 g, crude) and tosyl chloride (2.7 g, 14.21 mmol) in pyridine (8 mL) were stirred at room temperature for 1 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (70 mL) and water (60 mL). The organic layer was collected, washed with cold hydrochloric acid (1N, 80 mL) and then with brine (100 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a crude residue that was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography [eluted with 10–20% (vol/vol) ethyl acetate in hexane] to afford tert‐butyl 2‐(3‐{2‐[(4-methylbenzenesulfonyl)oxy]ethoxy}propoxy)acetate (3.9 g, yield 84%) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.48 (s, 9H), 1.78–1.85 (m, 2H), 2.45 (s, 3H), 3.49–3.56 (m, 4H), 3.62 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 4.15 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H).

Preparation of tert-butyl 2-(3-(2-aminoethoxy)propoxy)acetate (compound 14).

A mixture of tert‐butyl 2‐(3‐{2‐[(4-methylbenzenesulfonyl)oxy]ethoxy}propoxy)acetate (3.9 g, 10.04 mmol) and sodium azide (783 mg, 12.04 mmol) in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (10 mL) was stirred at 70 °C for 2 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature and was partitioned between ethyl acetate (70 mL) and water (30 mL). The organic layer was collected, washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a crude residue that was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography [eluted with 10–20% (vol/vol) ethyl acetate in hexane] to afford tert-butyl 2-(3-(2-azidoethoxy)propoxy)acetate (1.89 g, yield 73%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.48 (s, 9H), 1.89–1.94 (m, 2H), 3.36 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.59–3.64 (m, 6H), 3.96 (s, 2H). This oily material (1.79 g, 6.9 mmol), triphenylphosphine (2.71 g, 10.35 mmol), and water (0.6 mL) in tetrahydrofuran (20 mL) were stirred at room temperature for 3 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (60 mL) and water (30 mL). The organic layer was collected, washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a crude residue that was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography [eluted with 50–80% (vol/vol) ethyl acetate in hexane] to afford tert-butyl 2-(3-(2-aminoethoxy)propoxy)acetate (1.37 g, yield 85%) as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.48 (s, 9H), 1.87–1.94 (m, 2H), 2.85 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.45–3.48 (m, 2H), 3.57 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.61 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 2H).

Preparation of (2S, 4R)-1-[(2S)-2-{2-[3-(2-{2-[(9S)-7-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,5,13-trimethyl-3-thia-1,8,11,12-tetraazatricyclo[8.3.0.0 (2, 6)]trideca-2(6),4,7,10,12-pentaen-9-yl]acetamido}ethoxy)propoxy]acetamido}-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl]-4-hydroxy-N-[(1S)-1-[4-(4-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)phenyl]ethyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide (compound ARV-771).

HATU (2.65 mg, 6.97 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of (S)-2-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl) acetic acid (900 mg, 2.32 mmol, the carboxylic acid of JQ-1, prepared from JQ-1 in formic acid), tert-butyl 2-(3-(2-aminoethoxy)propoxy)acetate (650 mg, 2.79 mmol), and N-ethyl-N-isopropylpropan-2-amine (1.5 g, 11.61 mmol) in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (6 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 min. LC-MS showed that the reaction was complete. The mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (100 mL) and water (40 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (50 mL × 2). The combined organic layers were collected, washed with brine (100 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a crude residue that was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography [eluted with 2–10% (vol/vol) methanol in dichloromethane] to afford (S)-tert-butyl 2-(3-(2-(2-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)acetamido)ethoxy)propoxy)acetate (800 mg, yield 58%) as a white solid. This solid (800 mg, 1.30 mmol) in formic acid (5 mL) was stirred at 60 °C for 1 h. TLC showed that the reaction was complete. The volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure to afford (S)-2-(3-(2-(2-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)acetamido)ethoxy)propoxy)acetic acid as a crude yellow oil without further purification. The oily material (700 mg, crude), (2S,4R)-1-[(S)-2-amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl]-4-hydroxy-N-[(S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl]-pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (compound 7, 920 mg,1.91 mmol), and N-ethyl-N-isopropylpropan-2-amine (1.05 g, 8.11 mmol) in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (8 mL) were added to HATU (1.85 g, 4.87 mmol) at 0 °C, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 min. LC-MS showed that the reaction was complete. The mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (60 mL) and water (30 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (30 mL × 2). The combined organic layers were collected, washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a crude residue that was purified by preparative HPLC to afford ARV-771 (404.1 mg, yield 32%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 1.06 (s, 9H), 1.51 & 1.59 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1. 93–2.00 (m, 3H), 2.20–2.25 (m, 1H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.71 (s, 3H), 3.45–3.67 (m, 10H), 3.75–3.78 (m, 1H), 3.85–3.88 (m, 1H), 3.95–4.05 (m, 2H), 4.45 (br, 1H), 4.59–4.71 (m, 3H), 4.99–5.04 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.49 (m, 8H), 7.57 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H); LC-MS (ES+): m/z 986.4/988.4 [M+H+].

Preparation of (2R, 4S)-1-[(2S)-2-{2-[3-(2-{2-[(9S)-7-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,5,13-trimethyl-3-thia-1,8,11,12-tetraazatricyclo[8.3.0.0 (2, 6)]trideca-2(6),4,7,10,12-pentaen-9-yl]acetamido}ethoxy)propoxy]acetamido}-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl]-4-hydroxy-N-[(1S)-1-[4-(4-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)phenyl]ethyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide (compound ARV-766).

This compound was prepared using the procedure described for the synthesis of compound ARV-771 by using the key intermediate compound 10 instead of compound 7 to provide ARV-766 as an off-white powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.71–8.75 (m, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 7.83 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.43 (m, 9H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.02 Hz, 1H), 5.13 (t, J = 7.34 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (dd, J = 4.70, 8.61 Hz, 1H), 4.57–4.63 (m, 2H), 4.04–4.10 (m, 2H), 3.90 (d, J = 15.65 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (dd, J = 4.21, 10.66 Hz, 1H), 3.48–3.69 (m, 9H), 3.45 (d, J = 6.46 Hz, 1H), 3.27 (dd, J = 5.67, 14.87 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (s, 3H), 2.49–2.54 (m, 3H), 2.35–2.42 (m, 4H), 2.19 (s, 1H), 1.81–1.92 (m, 2H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.47 (d, J = 7.04 Hz, 3H), 1.02–1.12 (m, 9H). LC-MS (ES+): m/z 986.30/988.31 [M+H+].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.M.C. received support from NIH Grant R35CA197589.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: C.M.C. is the founder and Chief Scientific Advisor of, and possesses shares in, Arvinas, LLC.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1521738113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wong YNS, Ferraldeschi R, Attard G, de Bono J. Evolution of androgen receptor targeted therapy for advanced prostate cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(6):365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aragon-Ching JB. The evolution of prostate cancer therapy: Targeting the androgen receptor. Front Oncol. 2014;4:295. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trewartha D, Carter K. Advances in prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(11):823–824. doi: 10.1038/nrd4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mottet N, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;59(4):572–583. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CD, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karantanos T, Corn PG, Thompson TC. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: Mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene. 2013;32(49):5501–5511. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: Progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6(2):76–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bono JS, et al. COU-AA-301 Investigators Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan CJ, et al. COU-AA-302 Investigators Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):138–148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scher HI, et al. AFFIRM Investigators Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonarakis ES, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1028–1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J, Van der Steen T, Tindall DJ. Are androgen receptor variants a substitute for the full-length receptor? Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(3):137–144. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu C, Luo J. Decoding the androgen receptor splice variants. Transl Androl Urol. 2013;2(3):178–186. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2013.09.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprenger CCT, Plymate SR. The link between androgen receptor splice variants and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Horm Cancer. 2014;5(4):207–217. doi: 10.1007/s12672-014-0177-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu D, et al. Androgen receptor splice variants dimerize to transactivate target genes. Cancer Res. 2015;75(17):3663–3671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao B, et al. Androgen receptor splice variants activating the full-length receptor in mediating resistance to androgen-directed therapy. Oncotarget. 2014;5(6):1646–1656. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto Y, et al. Generation 2.5 antisense oligonucleotides targeting the androgen receptor and its splice variants suppress enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer cell growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(7):1675–1687. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzman DL, Antonarakis ES. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: Latest evidence and therapeutic implications. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2014;6(4):167–179. doi: 10.1177/1758834014529176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyce A, et al. Inhibition of BET bromodomain proteins as a therapeutic approach in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2013;4(12):2419–2429. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asangani IA, et al. Therapeutic targeting of BET bromodomain proteins in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2014;510(7504):278–282. doi: 10.1038/nature13229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Civenni G, et al. Abstract 2625: Targeting prostate cancer stem cells (CSCs) with the novel BET bromodomain (BRD) protein inhibitor OTX015. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2625. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan SC, et al. Targeting chromatin binding regulation of constitutively active AR variants to overcome prostate cancer resistance to endocrine-based therapies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(12):5880–5897. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, et al. Hijacking the E3 ubiquitin ligase cereblon to efficiently target BRD4. Chem Biol. 2015;22(6):755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zengerle M, Chan K-H, Ciulli A. Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(8):1770–1777. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter GE, et al. DRUG DEVELOPMENT. Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science. 2015;348(6241):1376–1381. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bondeson DP, et al. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(8):611–617. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckley DL, et al. HaloPROTACS: Use of small molecule PROTACs to induce degradation of HaloTag fusion proteins. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(8):1831–1837. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deshaies RJ. Protein degradation: Prime time for PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):634–635. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filippakopoulos P, Knapp S. Targeting bromodomains: Epigenetic readers of lysine acetylation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(5):337–356. doi: 10.1038/nrd4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckley DL, et al. Targeting the von Hippel-Lindau E3 ubiquitin ligase using small molecules to disrupt the VHL/HIF-1α interaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(10):4465–4468. doi: 10.1021/ja209924v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Filippakopoulos, et al. (2010) Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468:1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Qu Y, et al. Constitutively active AR-V7 plays an essential role in the development and progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7654. doi: 10.1038/srep07654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu R, et al. Distinct transcriptional programs mediated by the ligand-dependent full-length androgen receptor and its splice variants in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72(14):3457–3462. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprenger C, Uo T, Plymate S. Androgen receptor splice variant V7 (AR-V7) in circulating tumor cells: A coming of age for AR splice variants? Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1805–1807. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin L, et al. Role of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in negative regulation of PSMA expression. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Z, et al. Rapid induction of androgen receptor splice variants by androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(6):1590–1600. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson PA, et al. Constitutively active androgen receptor splice variants expressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer require full-length androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(39):16759–16765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolden JE, et al. Inducible in vivo silencing of Brd4 identifies potential toxicities of sustained BET protein inhibition. Cell Reports. 2014;8(6):1919–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shu S, et al. Response and resistance to BET bromodomain inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer. Nature. 2016;529(7586):413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature16508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcotte R, et al. Functional genomic landscape of human breast cancer drivers, vulnerabilities, and resistance. Cell. 2016;164(1-2):293–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belkina AC, Denis GV. BET domain co-regulators in obesity, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(7):465–477. doi: 10.1038/nrc3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi J, Vakoc CR. The mechanisms behind the therapeutic activity of BET bromodomain inhibition. Mol Cell. 2014;54(5):728–736. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.