Significance

Mammalian sperm possess a Golgi-derived exocytotic organelle, the acrosome, located on the apical region of the head. Proper biogenesis of the acrosome is essential for the fertilization process because the aberrant acrosome formation results in the sterility or subfertility of males. Here, we show that the acrosome formation is governed by two forms of proacrosin-binding protein ACRBP, wild-type ACRBP-W and variant ACRBP-V5, which are generated by pre-mRNA alternative splicing of Acrbp. ACRBP-V5 is involved in the formation and configuration of the acrosomal granule during early spermiogenesis, whereas the inactive status of proacrosin in the acrosome is maintained by ACRBP-W until acrosomal exocytosis.

Keywords: mouse, spermiogenesis, fertilization, acrosomal biogenesis, alternative splicing

Abstract

Proper biogenesis of a sperm-specific organelle, the acrosome, is essential for gamete interaction. An acrosomal matrix protein, ACRBP, is known as a proacrosin-binding protein. In mice, two forms of ACRBP, wild-type ACRBP-W and variant ACRBP-V5, are generated by pre-mRNA alternative splicing of Acrbp. Here, we demonstrate the functional roles of these two ACRBP proteins. ACRBP-null male mice lacking both proteins showed a severely reduced fertility, because of malformation of the acrosome. Notably, ACRBP-null spermatids failed to form a large acrosomal granule, leading to the fragmented structure of the acrosome. The acrosome malformation was rescued by transgenic expression of ACRBP-V5 in ACRBP-null spermatids. Moreover, exogenously expressed ACRBP-W blocked autoactivation of proacrosin in the acrosome. Thus, ACRBP-V5 functions in the formation and configuration of the acrosomal granule during early spermiogenesis. The major function of ACRBP-W is to retain the inactive status of proacrosin in the acrosome until acrosomal exocytosis.

The acrosome of mammalian sperm is a cap-shaped, exocytotic vesicle present on the apical surface of the head (1, 2). Acrosomal biogenesis takes place at the initial step of spermiogenesis, a process during which haploid spermatids differentiate into sperm and which can be divided into four phases: the Golgi, cap, acrosome, and maturation phases (1–5). In rodent spermatids, proacrosomal vesicles (granules) containing a variety of proteins assemble and fuse with one another to form a single, sphere acrosomal granule in the center of the acrosomal vesicle at the Golgi phase (1). At the cap phase, the acrosomal granule forms a head cap-like structure that gradually enlarges to cover the nucleus. The head cap continues to elongate outlining the dorsal edge, protruding apically at the acrosome phase, and then the structure of the acrosome is completed at the end of maturation phase.

The lumen of the acrosomal vesicle, which is surrounded by inner and outer acrosomal membranes, contains soluble and aggregated (acrosomal matrix) components (2, 5). The acrosome reaction is a fusion event between outer acrosomal and plasma membranes at multiple sites (2, 6). Consequently, the soluble components are dispersed from the acrosome, and the status of the sperm head is newly reorganized following gradual release of the matrix components (7). Sperm serine protease acrosin (ACR) localized in the acrosomal matrix has been shown to play a crucial role in dispersal of the acrosomal matrix components (8, 9). Because only acrosome-reacted sperm are capable of fusing with the oocyte plasma membrane, the acrosome reaction is physiologically essential for fertilization (2). Indeed, once sperm are acrosome-reacted, an acrosomal membrane-spanning protein, IZUMO1, migrates on the acrosomal membrane, is exposed on the surface of sperm head, and interacts with Juno glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored on the oocyte plasma membrane to achieve the sperm/oocyte fusion (10, 11).

An acrosomal protein, ACRBP (also known as sp32), is a binding protein specific for the precursor (proACR) and intermediate forms of ACR (12–14). ACRBP also has been identified as a member of the cancer/testis antigen family; ACRBP is normally expressed exclusively in the testis, but is also expressed in a wide range of different tumor types, including bladder, breast, liver, and lung carcinomas (15–17). Mammalian ACRBP is initially synthesized as a ∼60-kDa precursor protein (ACRBP-W) in spermatogenic cells, and the 32-kDa mature ACRBP (ACRBP-C) is posttranslationally produced by removal of the N-terminal half of the precursor ACRBP-W during spermatogenesis and/or epididymal maturation of sperm (14, 18). In the mouse, two forms of Acrbp mRNA, wild-type Acrbp-W and variant Acrbp-V5 mRNAs, are produced by pre-mRNA alternative splicing of Acrbp (18). Similarly to other mammalian ACRBP-W, mouse ACRBP-W starts to be synthesized in pachytene spermatocytes and immediately processed into ACRBP-C (Fig. S1). The intron 5-retaining splice variant mRNA produces a predominant form of ACRBP, ACRBP-V5, that is also present in pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids, but is absent in elongating spermatids (18). Functional analysis in vitro reveals that ACRBP-V5 and ACRBP-C possess a different domain capable of binding each of two segments in the C-terminal region of proACR (18). Moreover, autoactivation of proACR is remarkably accelerated by the presence of ACRBP-C (14, 18). Thus, we postulated that, at least in the mouse, ACRBP-V5 and ACRBP-C may differentially function in the transport/packaging of proACR into the acrosomal granule during spermiogenesis and in the promotion of ACR release from the acrosome during acrosomal exocytosis, respectively.

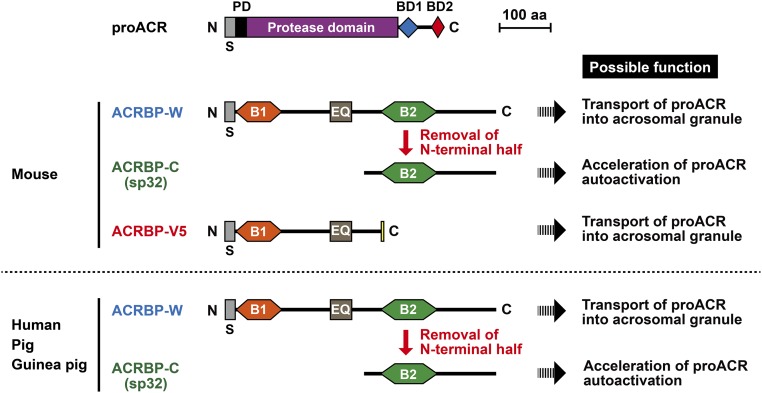

Fig. S1.

Schematic representation of mammalian proacrosin (proACR) and ACRBP. ACR, a trypsin-like serine protease, is initially synthesized as a prepro-protein with an N-terminal signal peptide (S) in pachytene spermatocytes and localized as proACR in the sperm acrosome. proACR is autoactivated by cleavage of the peptide bond between the prodomain (PD) and the protease domain and then is converted to the mature ACR by removal of the C-terminal domain containing two ACRBP-binding domains (BD1 and BD2). Another acrosomal protein, ACRBP, is a binding protein specific for the precursor (proACR) and intermediate forms of ACR. A precursor protein of ACRBP (ACRBP-W) is also synthesized in pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids, and the mature ACRBP (ACRBP-C known as sp32) is posttranslationally produced by removal of the N-terminal half of ACRBP-W during spermatogenesis and/or epididymal maturation of sperm. In the mouse, two forms of Acrbp mRNA, wild-type Acrbp-W and variant Acrbp-V5 mRNAs, are produced by pre-mRNA alternative splicing of Acrbp. Similarly to other mammalian ACRBP-W, mouse ACRBP-W is processed to ACRBP-C. The intron-5–retaining splice variant mRNA produces a predominant form of ACRBP, ACRBP-V5, that is present in pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids, but is absent in elongating spermatids. The protein sequence of ACRBP-V5 is distinguished from that of ACRBP-W by only five amino acids at the C terminus (yellow box), whereas both proteins contain a domain (EQ) rich in Glu and Gln. Moreover, ACRBP-W contains two different domains, B1 and B2, capable of binding BD2 and BD1 in the C-terminal region of proACR, respectively. Thus, ACRBP-C and ACRBP-V5 bind proACR through the interactions between B2 and BD1 and between B1 and BD2, respectively. Possible functions of ACRBP-W, ACRBP-V5, and ACRBP-C are also indicated.

In this study, to elucidate the physiological roles of ACRBP in spermiogenesis and fertilization, we have produced ACRBP-null mutant mice lacking both ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5. The mutant mice were then rescued by transgenic expression of ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5. The severely reduced fertility of ACRBP-null males was significantly recovered by introduction either of exogenous ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5. On the basis of the data obtained, the specialized functions of ACRBP-W/ACRBP-C and ACRBP-V5 in acrosome formation and acrosomal exocytosis are discussed.

Results

Generation of Mice Lacking ACRBP.

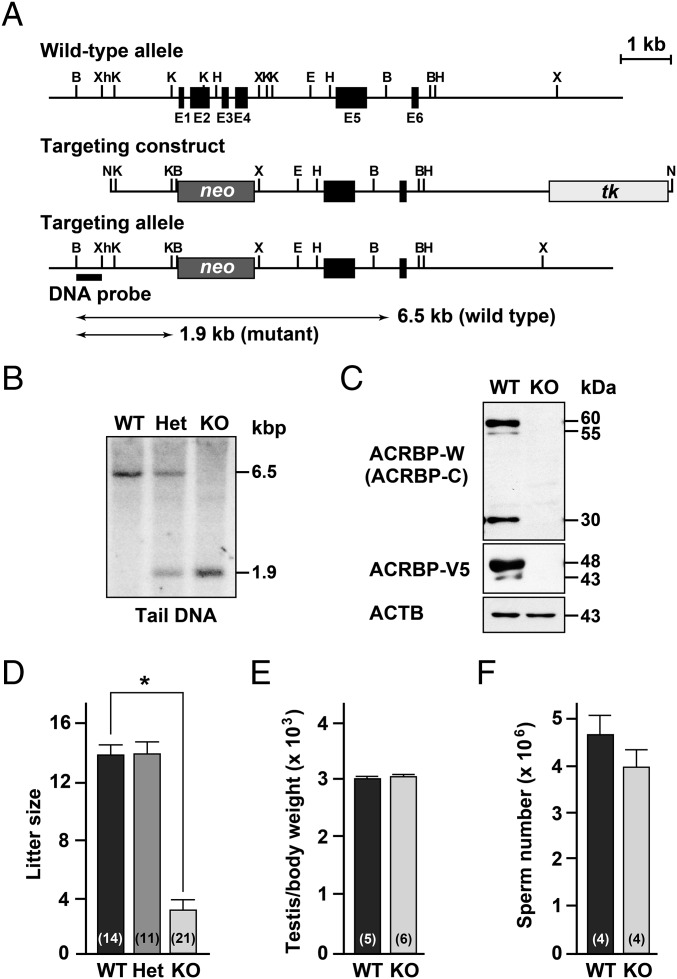

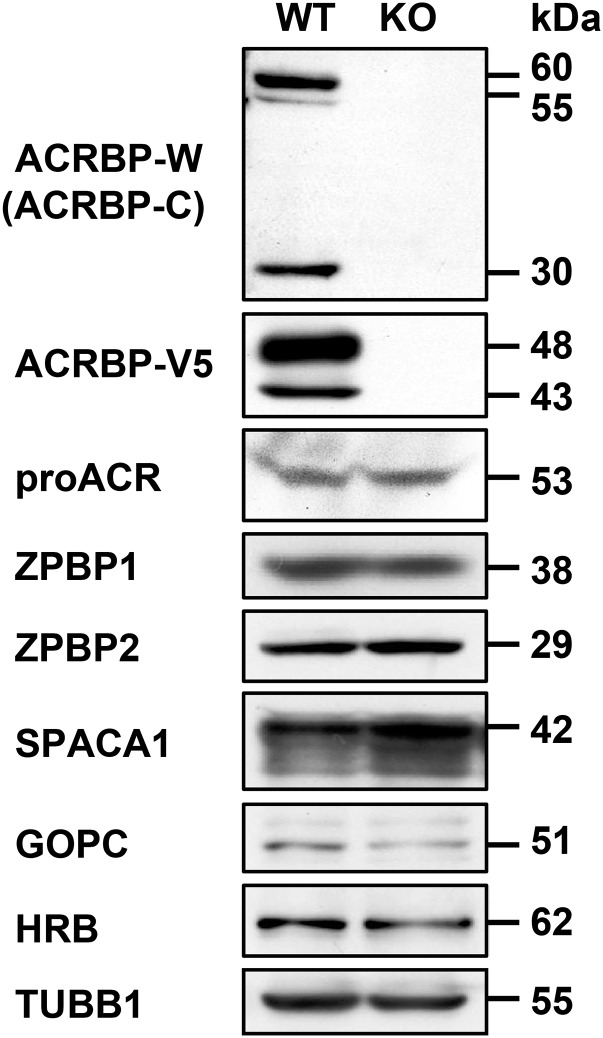

To uncover the functional role of ACRBP in spermiogenesis and fertilization, we produced mice carrying a null mutation of Acrbp using homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells. A targeting construct was designed to delete both ACRBP-W and the variant form ACRBP-V5 by replacing the 472-nucleotide protein-coding region of exons 1–4 with the neomycin-resistant gene neo (Fig. 1A). The genotype of wild-type (Acrbp+/+), heterozygous (Acrbp+/−), and homozygous (Acrbp−/−) mice for the targeted mutation of Acrbp were identified by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA (Fig. 1B). Immunoblot analysis of testicular protein extracts indicated the loss of 60/55- and 48/43-kDa doublets corresponding to ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5, respectively (Fig. 1C). The Acrbp−/− testis also lacked 30-kDa ACRBP-C (14, 18) posttranslationally produced from ACRBP-W during spermatogenesis. Mating of Acrbp+/− male and female mice yielded an expected Mendelian frequency of Acrbp−/− mice [Acrbp+/+:Acrbp+/−:Acrbp−/− = 25 (21%):64 (54%):29 (25%) for 118 offspring from 10 litters] (Fig. S2A). Acrbp−/− male and female mice were normal in behavior, body size, and health condition. Although Acrbp+/− males exhibited normal fertility, the fertility of Acrbp−/− males was dramatically reduced; 3 of 10 Acrbp−/− males produced no offspring a month after mating with wild-type females despite normal plug formation. Even when the females that mated with the Acrbp−/− males became pregnant, the litter sizes were significantly decreased (Fig. 1D). The Acrbp−/− females exhibited normal fertility (Fig. S2B). In addition, no significant difference in the testicular weight and the number of cauda epididymal sperm were found between Acrbp+/+ and Acrbp−/− (Fig. 1 E and F). These data demonstrate that the loss of ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 results in severely reduced male fertility.

Fig. 1.

Generation of ACRBP-deficient male mice. (A) Targeting strategy of Acrbp. Exons 1–4 (E1–E4, closed box) encoding the N-terminal 157-residue sequence of ACRBP (ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5) in Acrbp was replaced by neo (darkly shaded box). For negative selection, tk (lightly shaded box) was included at the 3′-end of the targeting construct. Restriction enzyme sites indicated are as follows: B, BamH1; Xh, XhoI; K, KpnI; H, HindIII; X, XbaI; E, EcoRI; N, NotI. (B) Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNAs from wild-type (Acrbp+/+, WT), heterozygous (Acrbp+/−, Het), and homozygous (Acrbp−/−, KO) mice were digested with BamHI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and subjected to Southern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled BamHI/XhoI fragment (DNA probe) as a probe. (C) Immunoblot analysis of testicular extracts. Proteins were probed with anti–ACRBP-C, anti–ACRBP-V5, and anti-ACTB (β-actin) antibodies. (D) Fertility of KO male mice. The WT, Het, and KO males (4, 6, and 10 different mice, respectively) were mated with WT females, and the litter sizes were counted. Total numbers of the WT females mated are indicated in parentheses. All statistical significances are calculated using the Student t test. *P < 0.01. Note that the WT and Het males examined were all fertile, and 3 of 10 KO males produced no offspring a month after mating with the females despite normal plug formation. (E and F) Testicular weight and sperm number of KO mice. The body and testis weights of WT and KO mice were measured 10–14 wk after birth (E). The numbers of sperm in the epididymides were also counted (F). The numbers in parentheses indicate those of males tested.

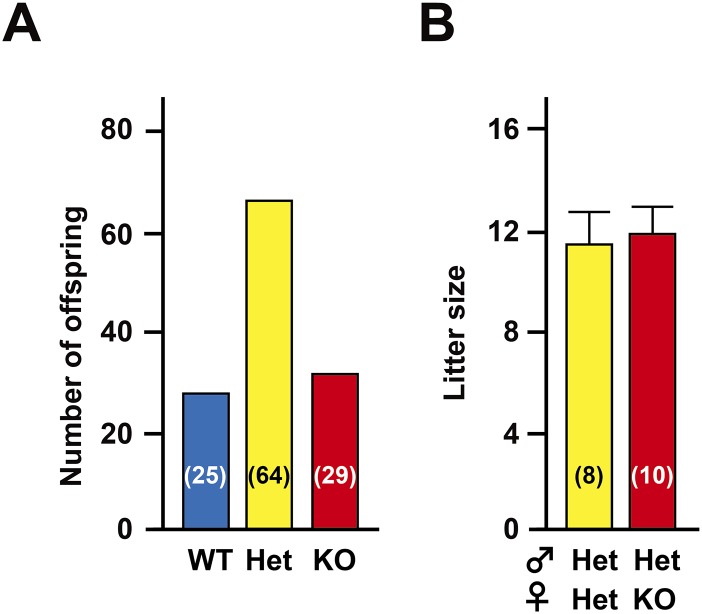

Fig. S2.

Fertility of mice carrying a null mutation of Acrbp. (A) Genotyping of offspring born. Male mice heterozygous for a null mutation of Acrbp (Het) were mated with the Het females. The genotypes of wild-type (WT), Het, and homozygous (KO) mice from a total of 10 litters were identified by PCR of tail DNAs. The numbers in parentheses indicate those of the offspring genotyped. (B) Fertility of KO females. The Het and KO female mice were mated with Het males, and the litter sizes were counted. The female mice examined were all fertile. The numbers in parentheses indicate those of the females mated. Data are represented as means ± SE.

Acrosome Formation in ACRBP-Deficient Testis.

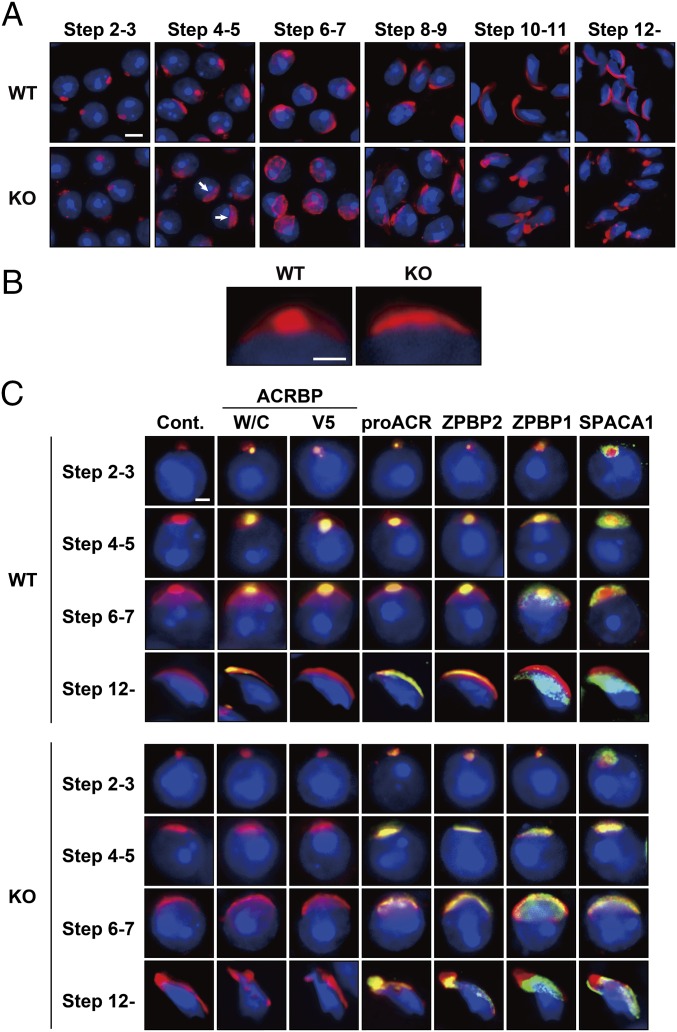

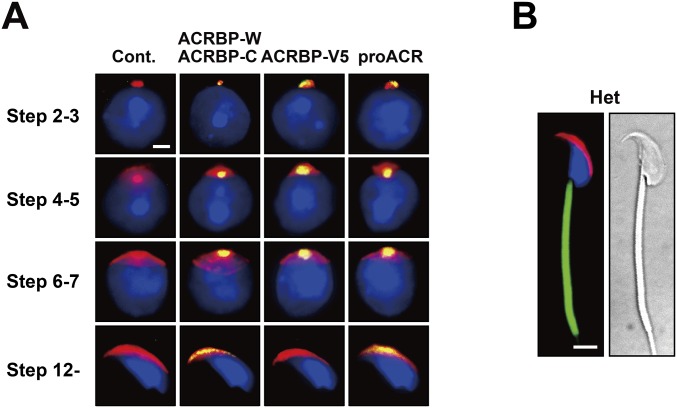

We next examined the acrosomal status of Acrbp−/− spermatogenic cells, using Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA) capable of binding mainly the outer acrosomal membrane (19). Consistent with already published reports (1, 20–22), a single, sphere acrosomal granule was formed in the center of the acrosomal vesicle of Acrbp+/+ spermatids by assembly of proacrosomal vesicles at steps 2 and 3 (Golgi phase) of spermiogenesis (Fig. 2A). The acrosomal granule gradually enlarged to form a head cap-like structure covering the nucleus at steps 4–7 (cap phase), and then the head cap further elongated, outlining the dorsal edge. In Acrbp−/− spermatids, proacrosomal vesicles normally assembled at the Golgi phase. However, Acrbp−/− spermatids at the cap phase lacked a large acrosomal granule (arrows in Fig. 2A), leading to a diffuse pattern of head cap distribution in the anterior region of the nucleus (Fig. 2B). Consequently, the acrosomal structure of Acrbp−/− spermatids was severely deformed at the later steps of spermiogenesis.

Fig. 2.

Abnormal acrosomal biogenesis in ACRBP-deficient spermatids. (A and B) Absence of acrosomal granule. Haploid spermatids of wild-type (WT) and ACRBP-deficient (KO) mice were stained with fluorescent dye-labeled lectin PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Note that KO spermatids display a diffused pattern of head cap distribution (arrows in A) because of the lack of a large acrosomal granule in the center of acrosomal vesicle. (Scale bars: 6.0 and 2.0 μm in A and B, respectively. (C) Subcellular localization of acrosomal proteins. Spermatids were immunostained with antibodies against proteins indicated (green). The acrosome and nucleus were also stained with fluorescent dye-labeled PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue), respectively. No immunoreactive signal was detected when preimmune serum was used as the probe (Cont.). (Scale bar, 2.0 μm.)

To examine the localization of acrosomal proteins in Acrbp−/− spermatids, we carried out immunostaining analysis using antibodies against four acrosomal proteins, ACRBP-W/ACRBP-C, ACRBP-V5, proACR, and ZPBP2, and two other proteins, ZPBP1 and SPACA1, attached and anchored on the inner acrosomal membrane at the equatorial segment, respectively (Fig. 2C). The levels of proACR, ZPBP2, ZPBP1, and SPACA1 in testicular extracts were comparable between Acrbp+/+ and Acrbp−/− mice (Fig. S3). ACRBP-W/ACRBP-C, ACRBP-V5, proACR, and ZPBP2 in Acrbp+/+ spermatids accumulated in the acrosomal granule until steps 6 and 7 and were then distributed along the dorsal edge of the sperm head. ZPBP1 and SPACA1 were initially present around the acrosomal granule and then spread to the equatorial region, as described previously (23, 24). Essentially similar results were obtained in Acrbp+/− spermatids (Fig. S4A). The assembly of acrosomal proteins in Acrbp−/− spermatids was normal at the Golgi phase (Fig. 2C). However, these proteins were localized throughout the acrosomal vesicle at the early cap phase, without forming an acrosomal granule-like structure, and then scattered over the nucleus, because of the fragmented structures of acrosome.

Fig. S3.

Immunoblot analysis. Proteins in testicular extracts from wild-type (WT) and ACRBP-deficient (KO) mice were separated by SDS/PAGE and probed with antibodies against the proteins indicated.

Fig. S4.

Morphological analysis of Acrbp+/− spermatids and epididymal sperm. (A) Subcellular localization of acrosomal proteins. Acrbp+/− spermatids were immunostained with antibodies against proteins indicated (green). The acrosome and nucleus were also stained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue), respectively. No immunoreactive signal was detected when preimmune serum was used as the probe (Cont.). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (B) Sperm morphology. The acrosome, mitochondria, and nucleus of Acrbp+/− (Het) epididymal sperm were stained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red), MitoTracker Green FM (green), and Hochest 33342 (blue), respectively. (Scale bar, 4 μm.)

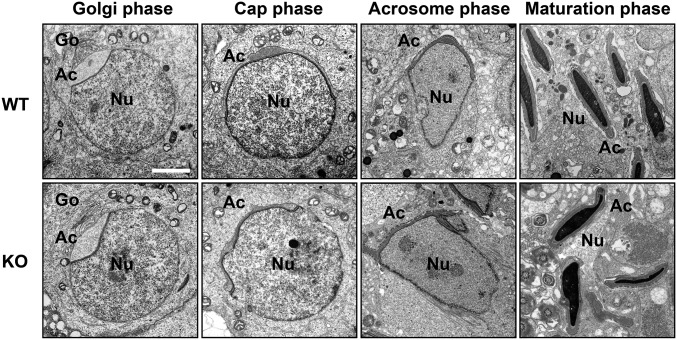

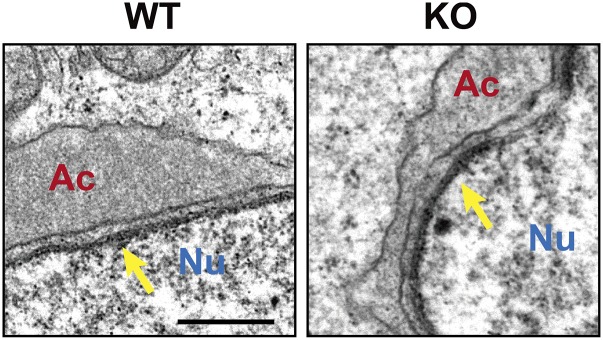

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images indicated no obvious difference in the morphology of spermatids at the Golgi phase between Acrbp+/+ and Acrbp−/− mice (Fig. 3). The acrosomal vesicle was located adjacent to the Golgi apparatus having a well-defined polarized structure with ordered stacks of sacculi. However, Acrbp−/− spermatids at the cap phase displayed at least two morphological defects in the acrosome, compared with Acrbp+/+ spermatids: the abnormal shape of the acrosomal vesicle and the lack of the electron-dense acrosomal granule in the center of acrosomal vesicle. As spermiogenesis proceeded, the morphological abnormality of the acrosome in Acrbp−/− spermatids became more severe. In addition to the acrosome, the nucleus of Acrbp−/− spermatids was deformed to some extent (Fig. 3 and Fig. S5). These results suggest that either ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5 or both may play essential roles in the formation of the sphere acrosomal granule and in the retention of acrosomal proteins in the acrosomal granule.

Fig. 3.

Abnormal morphology of ACRBP-deficient spermatids. Ultrathin sections of spermatids from wild-type (WT) and ACRBP-deficient (KO) mice were analyzed by TEM. Ac, acrosomal vesicle; Go, Golgi apparatus; Nu, nucleus. (Scale bar, 2.0 μm.)

Fig. S5.

Nuclear morphology of ACRBP-deficient spermatids. Ultrathin sections of wild-type (WT) and ACRBP-deficient (KO) mice were analyzed by TEM. Arrows indicate acroplaxome. Ac, acrosomal vesicle; Nu, nucleus. (Scale bar, 0.5 μm.)

Characterization of ACRBP-Deficient Epididymal Sperm.

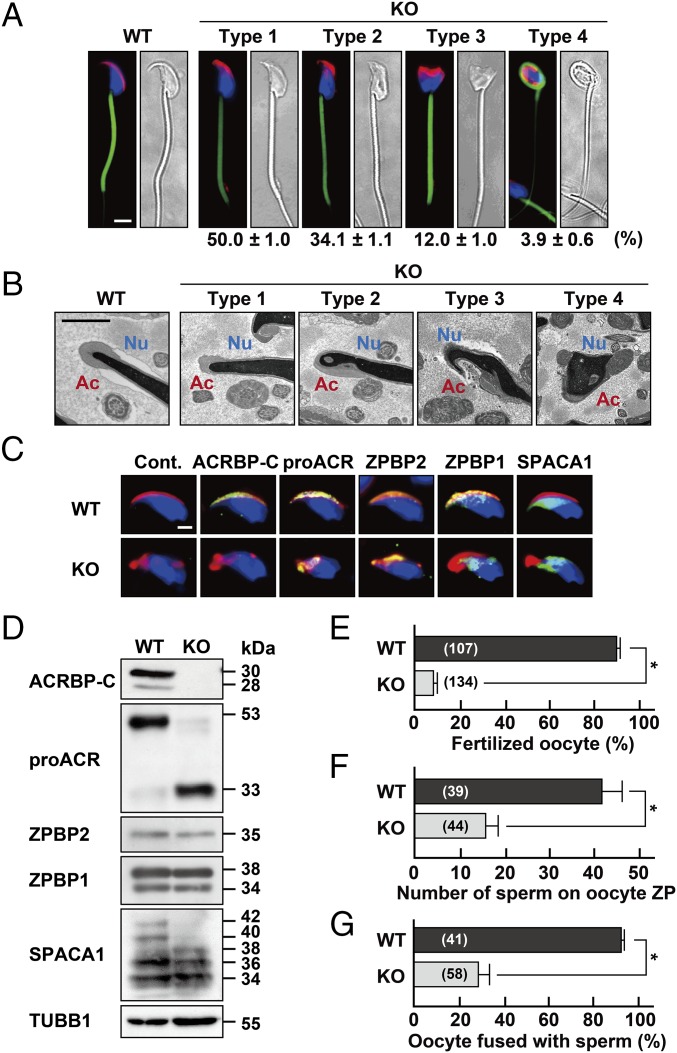

Because Acrbp−/− male mice exhibited a severely reduced fertility (Fig. 1D), we asked whether cauda epididymal sperm of Acrbp−/− mice are morphologically and functionally normal. Although the hook-shaped acrosome in Acrbp+/+ sperm was also observed in Acrbp+/− sperm (Fig. S4B), Acrbp−/− sperm exhibited a continuous variation in the shapes of the acrosome and nucleus (Fig. 4A). We thus divided the whole population of Acrbp−/− sperm into four types (types 1, 2, 3, and 4). The nucleus of type 1 Acrbp−/− sperm was morphologically similar to that of Acrbp+/+ sperm, despite the fact that the acrosome of type 1 sperm was partially fragmented on the head or was not fully elongated to the dorsal edge. The nuclear shapes of type 2 and type 3 sperm were moderately and severely affected, respectively, in addition to the fragmented structure of acrosome. Moreover, type 4 sperm displayed both the fragmented acrosome and a round-headed shape with a coiled midpiece around the deformed nucleus, similarly to GOPC-, ZPBP1-, and SPACA1-null sperm (23–25). The rates of type 1, type 2, type 3, and type 4 sperm were ∼50%, 34%, 12%, and 4% of total Acrbp−/− sperm, respectively. The morphological change may occur during sperm maturation in the epididymis, as is the case for GOPC- and ZPBP1-null sperm (23, 25) because the type 4 sperm was barely found in the Acrbp−/− testis. When the morphology of Acrbp−/− sperm was further analyzed by TEM, the acrosome and nucleus showed structural abnormalities (Fig. 4B). All types of Acrbp−/− sperm possessed the deformed acrosome. Notably, the nucleus of type 2, type 3, and type 4 sperm was abnormally condensed, indicating that the defect in the nuclear condensation is accompanied by the loss of ACRBP. However, Acrbp−/− sperm as well as Acrbp+/+ sperm contained the typical 9 + 2 microtubule axoneme in the flagella. Immunostaining analysis of Acrbp−/− sperm verified the aberrant localization of proACR, ZPBP2, ZPBP1, and SPACA1 on the head, although two acrosomal proteins, proACR and ZPBP2, were still present predominantly in the fragmented acrosomal vesicles (Fig. 4C). Thus, the loss of ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 in spermatids is linked to the abnormal structure of epididymal sperm.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of ACRBP-deficient epididymal sperm. (A) Sperm morphology. The acrosome, mitochondria, and nucleus of cauda epididymal sperm from wild-type (WT) and ACRBP-deficient (KO) mice were stained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red), MitoTracker Green FM (green), and Hochest 33342 (blue), respectively. The KO sperm were morphologically divided into four types, and the rate of each cell type was determined. (Scale bar, 4.0 μm.) (B) TEM analysis. Ac, acrosome; Nu, nucleus. (Scale bar, 1.0 μm.) (C) Immunostaining analysis. Sperm were immunostained with antibodies against proteins indicated (green) and also stained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). No immunoreactive signal was detected when preimmune serum was used as the probe (Cont.). (Scale bar, 2.0 μm.) (D) Immunoblot analysis. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and probed with antibodies against the sperm proteins indicated. (E–G) Functional assays of sperm. Capacitated sperm were subjected to assays for IVF (E), sperm/ZP binding (F), and sperm/oocyte fusion (G). The numbers in parentheses indicate those of the oocytes examined. All statistical significances are calculated using the Student t test. *P < 0.01.

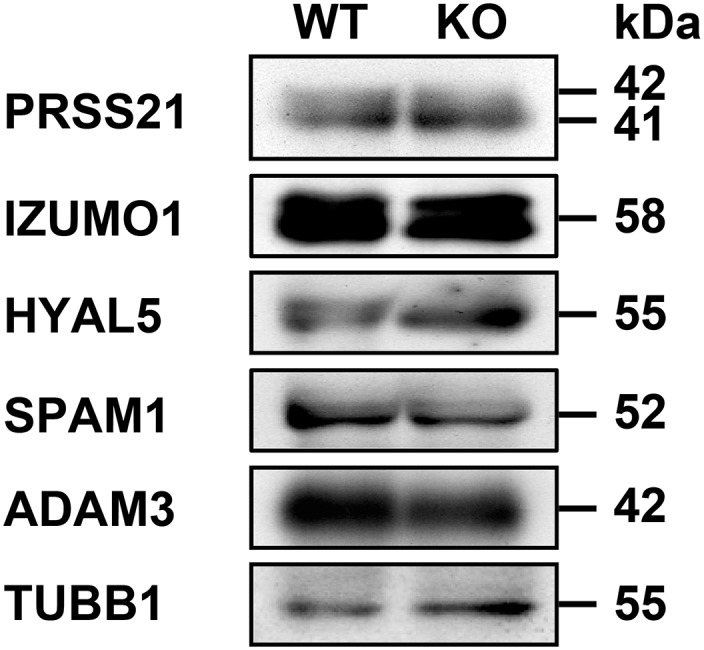

To examine whether acrosomal proteins, including proACR, are quantitatively and qualitatively affected by the loss of ACRBP, we carried out immunoblot analysis of protein extracts from epididymal sperm (Fig. 4D). Intriguingly, proACR was mostly processed into a mature form of ACR in Acrbp−/− sperm, whereas the levels of ZPBP1 and ZPBP2 were similar between Acrbp+/+ and Acrbp−/− sperm. The 42- and 40-kDa forms of SPACA1 also exhibited a very low abundance in Acrbp−/− sperm. In addition, Acrbp−/− sperm normally contained five membrane proteins, IZUMO1 (10), zona pellucida (ZP)-binding protein ADAM3 (26), hyaluronidases SPAM1 and HYAL5 (27, 28), and GPI-anchored serine protease PRSS21 (29), as shown in Fig. S6. Thus, ACRBP is required for the maintenance of the enzymatically inactive ACR zymogen (proACR) in the acrosome. It is also suggested that SPACA1 may be one of the target proteins for ACR.

Fig. S6.

Immunoblot analysis. Proteins in extracts of cauda epididymal sperm from wild-type (WT) and ACRBP-deficient (KO) mice were separated by SDS/PAGE and probed with antibodies against proteins indicated.

We next examined the function of Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm. In vitro fertilization (IVF) assays using cumulus-intact oocytes indicated a pronounced defect of Acrbp−/− sperm in fertilizing the oocytes (Fig. 4E). The IVF rate in Acrbp−/− sperm was less than 10% of that in Acrbp+/+ sperm. The abilities of Acrbp−/− sperm to bind the cumulus-free oocyte ZP and to fuse with the ZP-free oocytes were also diminished markedly (Fig. 4 F and G). Computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA) of capacitated epididymal sperm revealed that the rates of three parameters—total motility, rapid motility, and hyperactivation—in Acrbp−/− mice were significantly lower than those in Acrbp+/+ mice (Table S1). Notably, Acrbp−/− sperm exhibited a remarkably high rate of static cells. We also examined the motility of each type of Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm by live imaging (Movie S1). Type 1 Acrbp−/− sperm were indistinguishable from the type 2 sperm based on morphology, without staining of the acrosome and nucleus. Compared with Acrbp+/+ sperm, type 1/type 2 Acrbp−/− sperm were characterized by irregular patterns of flagellar beating and head rotations. The flagellar beating of the type 3 sperm was fairly dysfunctional, whereas the type 4 sperm displayed the loss in the forward movement. In addition to the aberrant flagellar beating, Acrbp−/− sperm, as well as mouse sperm lacking either one of catalytic subunit PPP3CC and regulatory subunit PPP3R2 of Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent serine-threonine phosphatase calcineurin (30), exhibited the defect in the bending motion of the midpiece. The frequencies of the midpiece bending in type 1/type 2 and type 3 Acrbp−/− sperm were modestly and severely reduced, respectively. The abnormal bending motion in Acrbp−/− sperm may be due to the deformed structure of the acrosome because ACRBP is localized exclusively in the acrosome (18). We could not examine the type 4 sperm, because of the entwinement of the midpiece around the nucleus (Fig. 4A). These data demonstrate the severely impaired function of Acrbp−/− sperm in vitro, consistent with the reduced fertility of Acrbp−/− male mice (Fig. 1D).

Table S1.

Motility of capacitated epididymal sperm

| Mouse sperm | ||

| CASA parameter | Wild type | ACRBP-null† |

| Total motility (%) | 86.8 ± 4.4 | 61.4 ± 4.0*, |

| Progressive motility (%) | 55.0 ± 2.8 | 32.8 ± 3.4* |

| Rapid motility (%) | 66.6 ± 3.4 | 36.2 ± 3.4* |

| Static cell (%) | 13.2 ± 4.4 | 38.6 ± 4.0* |

| Average path velocity (μm/s) | 115.4 ± 5.6 | 104.1 ± 6.0 |

| Amplitude of lateral head displacement (μm) | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.6** |

| Linearity (%) | 43.2 ± 0.7 | 51.0 ± 2.1* |

| Hyperactivation (%)‡ | 25.2 ± 2.9 | 19.8 ± 3.0* |

Cauda epididymal sperm were capacitated by incubation in TYH medium for 2 h and subjected to CASA. At least 200 sperm were examined from each sperm sample from three different mice (n = 3).

All statistical significances were calculated using the Student t test (*P < 0.01; **P < 0.05).

Hyperactivated motility of sperm was defined as velocity of curvilinear ≥ 180 μm/s, amplitude of lateral head displacement ≥ 9.5 μm, and linearity ≤ 38%.

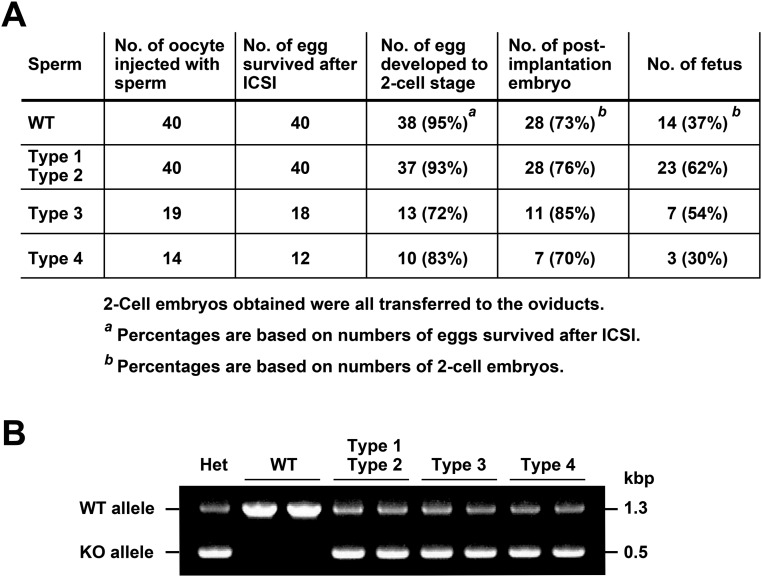

Globozoospermia, a severe form of teratozoospermia, is a human infertility syndrome characterized by a round-headed morphology of sperm without an acrosome (31, 32). The intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatment for globozoospermia patients results in a low success rate of fertilization, because of a reduced ability to activate the oocytes. In this study, we ascertained whether the oocytes are activated by ICSI using Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm (Fig. S7A). Most of the oocytes microinjected with the heads of type 1/type 2 or type 3 Acrbp−/− sperm (the whole cell for the type 4 sperm due to the failure to separate the head and tail) were successfully activated and reached the two-cell stage. All fetuses derived from Acrbp−/− sperm were verified to possess the Acrbp-null allele (Fig. S7B). Thus, despite the abnormal nuclear condensation, the nucleus of Acrbp−/− sperm is functionally active in pronuclear formation and subsequent embryonic development.

Fig. S7.

Development of mouse oocytes after ICSI using ACRBP-deficient sperm. (A) Development of the oocytes following microinjection of sperm. The head of a single epididymal sperm from wild-type mice (WT), type 1/type 2, or type 3 Acrbp−/− mice was separated from the tail by applying a few Piezo pulses and injected into the cumulus-free oocyte. The injected oocytes were cultured at 37 °C for 24 h under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. Embryos that reached the two-cell stage were transferred into the oviducts of pseudopregnant mice on the day after sterile mating with a vasectomized male (day 0.5). On day 19.5, the uteri of the recipient mice were examined for the presence of live term fetuses. Note that type 1 Acrbp−/− sperm were indistinguishable from the type 2 sperm based on morphology, without staining of the acrosome and nucleus, and that the type 4 sperm, whose head and tail could not be separated by Piezo pulses, were injected as the whole cell. (B) Genotyping of ICSI-derived fetuses. PCR was carried out using fetal genomic DNAs as templates. The tail DNA of Acrbp+/− mouse (Het) was also analyzed by PCR as a control. Two DNA fragments with the sizes of 1.3 and 0.5 kbp, originated from the wild-type (WT) and null-mutated (KO) alleles, respectively, were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Production of Transgenic Mice Expressing Exogenous ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5.

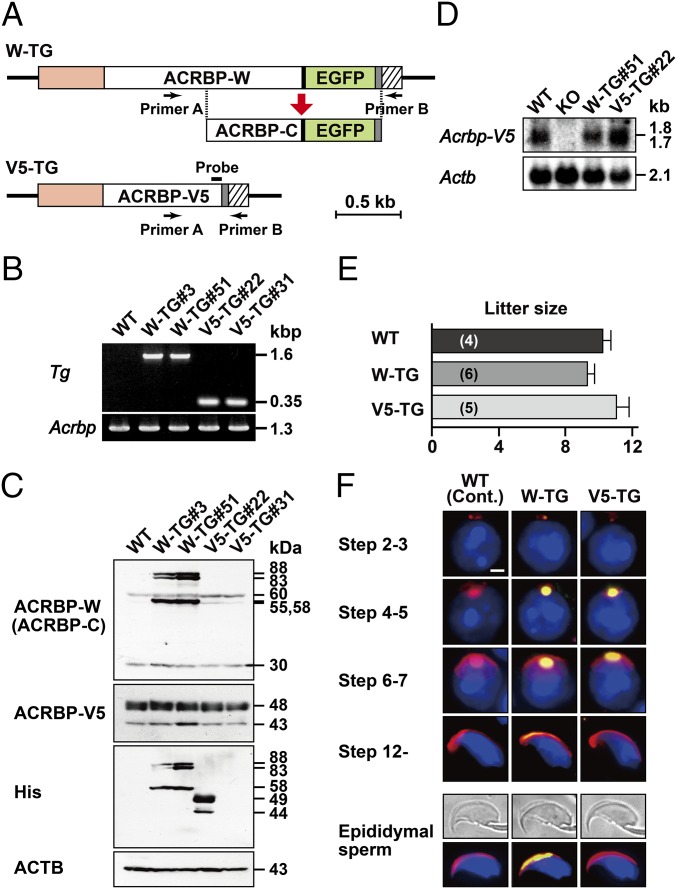

We generated two transgenic mouse lines (WTW-TG and WTV5-TG) expressing exogenous ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 under the control of the Acrbp promoter, respectively (Fig. 5A). The entire protein-coding region of ACRBP-W was designed to fuse with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). The transgenically expressed ACRBP-W-EGFP and ACRBP-V5 proteins also contained a myc-His tag at the C terminus. We randomly selected two lines each of WTW-TG (#3 and #51) and WTV5-TG (#22 and #31) mice from seven and five transgene-expressing lines, respectively (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Establishment and characterization of transgenic mouse lines expressing exogenous ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5. (A) Transgene constructs. Two transgene constructs encoding ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 (W-TG and V5-TG, respectively) were designed to include the Acrbp promoter region (orange) at the 5′-end. The protein-coding regions of ACRBP-W, ACRBP-V5, and EGFP are indicated by open and green boxes, respectively. Closed, shaded, and hatched boxes represent the Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly linker, the myc-His tag, and the 3′-untranslated region of the bovine growth hormone gene, respectively. The location of a PCR primer set (primer A and primer B) is also indicated by arrows. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR product. Two transgenic mouse lines, WTW-TG and WTV5-TG, were established. PCR was carried out using tail genomic DNAs of each of the wild-type (WT), WTW-TG#3, WTW-TG#51, WTV5-TG#22, and WTV5-TG#31 mice as a template (Tg). Endogenous Acrbp as a control was also examined by PCR analysis (Acrbp). (C) Immunoblot analysis of testicular extracts. Proteins were probed with anti–ACRBP-C, anti–ACRBP-V5, anti–His-Tag, and anti-ACTB antibodies. (D) Northern blot analysis. Total cellular RNAs of testicular tissues from WT, ACRBP-deficient (KO), WTW-TG#51, and WTV5-TG#22 mice were probed with 32P-labeled DNA fragment coding for ACRBP-V5 (A) or ACTB as probes. (E) Fertility of transgenic male mice. The WT, WTW-TG#51, and WTV5-TG#22 males (two different mice for each) were mated with WT females, and the litter sizes were counted. The males were all fertile. The numbers in parentheses indicate those of the WT females mated. (F) Immunostaining analysis. The subcellular localization of exogenously expressed ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 in spermatids and epididymal sperm was examined by immunostaining with anti-Myc antibody (green). No immunoreactive signal was detected in WT spermatids and sperm when preimmune serum was used as the probe (Cont.). Cells were also counterstained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). (Scale bar, 2.0 μm.)

Immunoblot analysis indicated that testicular extracts of WTW-TG#3 and WTW-TG#51 mice contain an 88/83-kDa doublet and a 58-kDa protein corresponding to myc-His–tagged ACRBP-W-EGFP and ACRBP-C-EGFP, respectively (Fig. 5C), in addition to endogenous 60/55-kDa ACRBP-W and 30-kDa ACRBP-C (18). The levels of ACRBP-W-EGFP and ACRBP-C-EGFP in the WTW-TG#3 and WTW-TG#51 testes were more than threefold higher than those of endogenous ACRBP-W and ACRBP-C in the wild-type, WTW-TG#3, and WTW-TG#51 testes. When the blots were probed with anti–ACRBP-V5 antibody, the abundance of endogenous ACRBP-V5 as a 48/43-kDa doublet (18) was comparable among wild-type and four transgenic mice including WTV5-TG#22 and WTV5-TG#31 mice. Because no immunoreactive band corresponding to exogenously expressed ACRBP-V5 tagged with myc-His was detectable, we used anti-His antibody as a probe (Fig. 5C). A doublet of 49- and 44-kDa myc-His–tagged ACRBP-V5 proteins was found only in the WTV5-TG#22 testis, indicating that anti–ACRBP-V5 antibody raised against the C-terminal seven-residue peptide of ACRBP-V5 (18) poorly recognizes myc-His–tagged ACRBP-V5. To estimate the expression level of exogenous ACRBP-V5, we carried out Northern blot analysis of testicular total RNAs (Fig. 5D). The level of Acrbp-V5 mRNA in WTV5-TG#22 testis was approximately twice as abundant as those in the wild-type and WTW-TG#51 testes. Assuming that the WTV5-TG#22 testis contains a mixture of endogenously and exogenously expressed Acrbp-V5 mRNAs with approximate sizes of 1.7 and 1.8 kb, respectively, these two mRNAs are equivalently expressed in the WTV5-TG#22 testis. We thus selected WTW-TG#51 and WTV5-TG#22 transgenic mice for further analysis.

WTW-TG#51 and WTV5-TG#22 males were all fertile and produced normal litter sizes when mated with wild-type females (Fig. 5E). Immunostaining analysis verified that acrosome formation in spermatids of the WTW-TG#51 and WTV5-TG#22 testes is normal (Fig. 5F). The localization of exogenously expressed ACRBP-W-EGFP and ACRBP-V5 in acrosomal vesicles was similar to those of endogenous ACRBPs (Figs. 2C and 5F). Consistent with our previous data (18), no exogenous ACRBP-V5 was found in the acrosome of cauda epididymal sperm. Thus, acrosome formation is unaffected by transgenic expression of ACRBP-W-EGFP and ACRBP-V5 in spermatids.

Rescue of Phenotypical Abnormality in ACRBP-Deficient Mice.

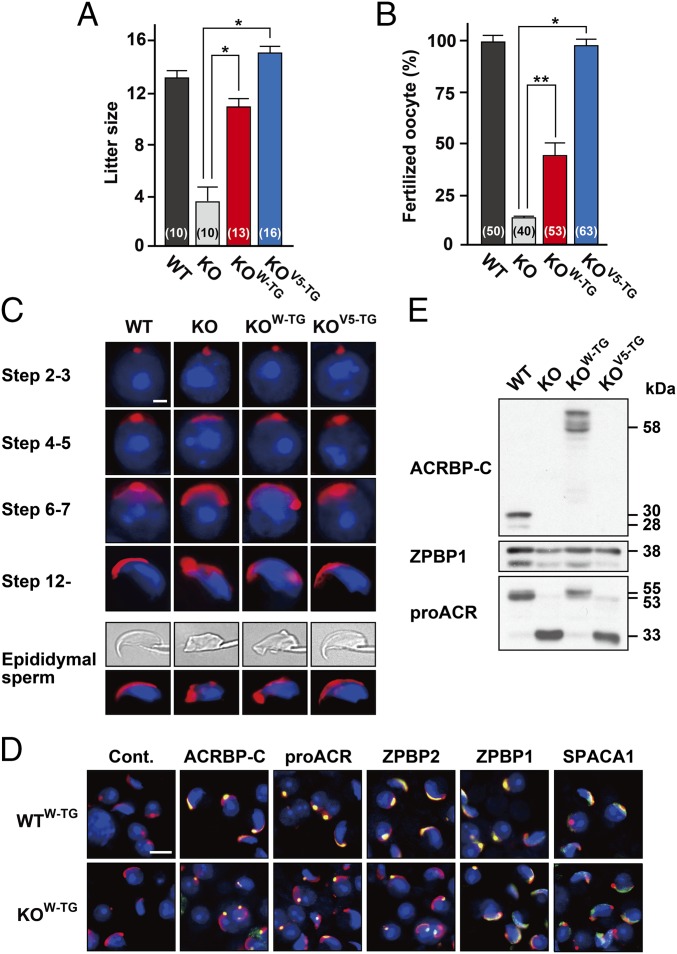

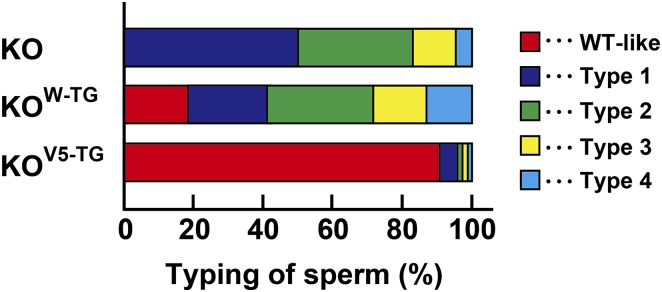

To examine whether the phenotypical abnormality of Acrbp−/− mice is rescued by transgenic introduction of ACRBP-W-EGFP or ACRBP-V5 into the knockout background, Acrbp−/− mice carrying the Acrbp-W-EGFP (termed KOW-TG) or Acrbp-V5 transgene (KOV5-TG) were obtained by crossing between Acrbp−/− and WTW-TG#51 or WTV5-TG#22 mice and then by mating the F1 males with Acrbp−/− females. Mating of KOV5-TG male mice with wild-type females resulted in an average litter size similar to that obtained by the wild-type pairs (Fig. 6A). KOW-TG males also exhibited a significant increase in the litter sizes compared with Acrbp−/− males. The impaired fertility of Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm in vitro was recovered moderately and greatly by exogenous expression of ACRBP-W-EGFP and ACRBP-V5, respectively (Fig. 6B). Formation of acrosomal granules was normal in KOW-TG and KOV5-TG spermatids at the Golgi phase (Fig. 6C). Importantly, the fragmented acrosomal structure of elongating spermatids and epididymal sperm in Acrbp−/− mice was recovered to a nearly normal level by exogenous ACRBP-V5 expression. Similarly to ZPBP1-null spermatids (23), the acrosomal granules in KOW-TG spermatids were eccentrically localized in the acrosomal vesicle at the cap phase. Indeed, immunostaining of KOW-TG spermatids revealed that spermatogenic cell-specific proteins, including proACR and ZPBP2, in acrosomal granules are not distributed in the center of acrosomal vesicles (Fig. 6D). When the acrosome and nucleus of epididymal sperm from KOV5-TG mice were stained with fluorescent probes, ∼90% of total KOV5-TG sperm displayed a morphology comparable to that of wild-type sperm (Fig. S8). However, KOW-TG mice possessed only a limited number of wild-type–like sperm (almost 18% of total cells) and still contained type 1, type 2, type 3, and type 4 sperm at the rates of 22%, 31%, 16%, and 13%, respectively. Thus, ACRBP-V5 plays a crucial role in the formation and configuration of the acrosomal granule during spermiogenesis. It is also suggested that ACRBP-W partially contributes to acrosomal granule formation and is not implicated in the configuration of the acrosomal granule in the acrosomal vesicle.

Fig. 6.

Rescue of phenotypical abnormality in ACRBP-deficient spermatids by transgenic expression of ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5. (A) Fertility. ACRBP-deficient (KO) male mice carrying the ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 transgenes (KOW-TG and KOV5-TG mice, respectively) were generated. The wild-type (WT), KO, KOW-TG, and KOV5-TG males (three, three, three, and four different mice, respectively) were mated with WT females, and the litter sizes were counted. The male mice examined were all fertile. The numbers in parentheses indicate those of the WT females mated. All statistical significances are calculated using the Student t test. *P < 0.01. (B) IVF assays. Capacitated cauda epididymal sperm were subjected to IVF assays using the cumulus-intact oocytes. The numbers in parentheses indicate those of the oocytes examined. **P < 0.05; *P < 0.01. (C) Morphological analysis. Spermatids and cauda epididymal sperm were stained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). (Scale bar, 2.0 μm.) (D) Subcellular localization of acrosomal proteins. Spermatids were immunostained with antibodies against the proteins indicated (green). The acrosome and nucleus were also stained with fluorescent-dye–labeled PNA (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue), respectively. No immunoreactive signal was detected when preimmune serum was used as the probe (Cont.). (Scale bar, 8.0 μm.) (E) Immunoblot analysis. Proteins of epididymal sperm extracts from WT, KO, KOW-TG, and KOV5-TG mice were probed with anti–ACRBP-C, anti-proACR, and anti-ZPBP1 antibodies.

Fig. S8.

Rescue of phenotypical abnormality in ACRBP-deficient mice. Cauda epididymal sperm of ACRBP-deficient mice (KO) expressing the Acrbp-W-EGFP (KOW-TG) or Acrbp-V5 transgene (KOV5-TG) were divided into four types (types 1, 2, 3, and 4) based on the acrosomal and nuclear morphologies, as described in Fig. 4A. KOW-TG and KOV5-TG sperm were stained with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated PNA and Hoechst 33342, randomly selected (200 cells per each assay) and counted. For comparison, the rate of each type of KO sperm is shown (Fig. 4A). WT-like, sperm showing the morphology comparable to that of wild-type sperm.

We also asked whether aberrant processing of proACR in Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm (Fig. 4D) occurs when either ACRBP-W-EGFP or ACRBP-V5 is exogenously expressed. Immunoblot analysis of epididymal sperm extracts revealed that proACR remains unprocessed in KOW-TG mice (Fig. 6E). In contrast, proACR in KOV5-TG sperm was converted mostly to a 33-kDa form of ACR, similarly to Acrbp−/− sperm. These data suggest that ACRBP-C functions in the maintenance of proACR as an enzymatically inactive ACR zymogen in the acrosome.

Discussion

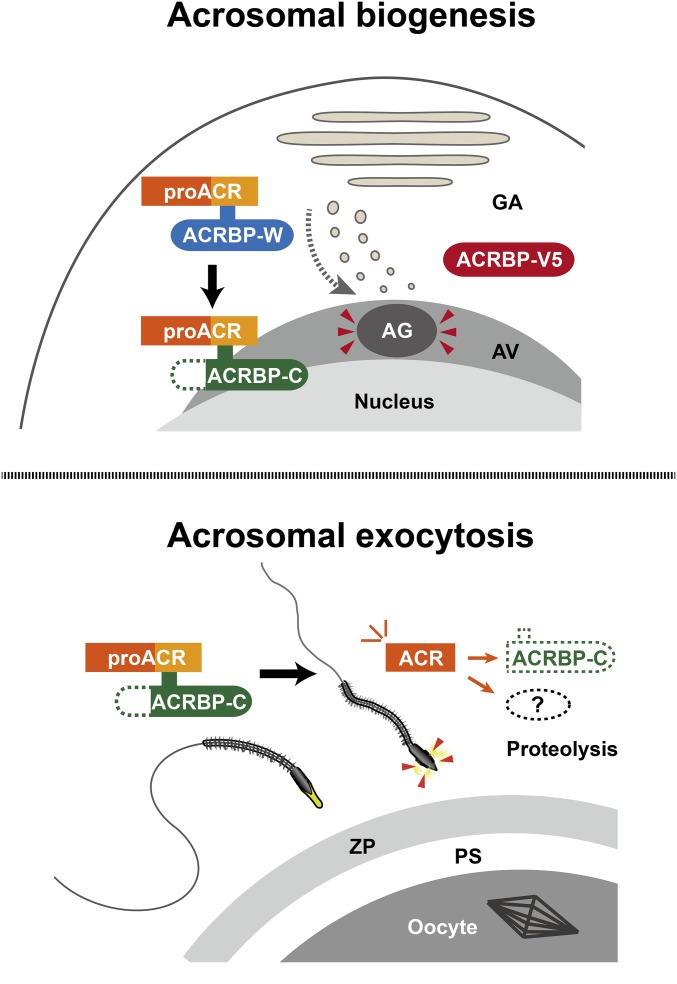

This study describes the functional specialization of two ACRBP proteins, ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5, that are produced by pre-mRNA alternative splicing in the mouse (18). The Acrbp−/− male mice lacking both ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 show a severely reduced fertility (Fig. 1), because of aberrant formation of the acrosome (Figs. 2 and 3). Although proacrosomal vesicles normally assemble, Acrbp−/− early spermatids fail to form a large acrosomal granule (Fig. 2). The impaired ability to produce the acrosomal granule in the Acrbp−/− spermatids is linked to the fragmented structure of the acrosome, further leading to the abnormally round-headed shape structure and reduced motility of Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm (Fig. 4 and Table S1). The aberrant formation of the acrosomal granule is recovered by transgenic expression of either ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5 in Acrbp−/− spermatids, although exogenous ACRBP-W expression results in the eccentric localization of the acrosomal granule in the acrosome vesicle (Fig. 6). Moreover, transgenic introduction of ACRBP-W maintains proACR as an enzymatically inactive zymogen in the acrosome by preventing the zymogen from processing into a mature form of ACR (Fig. 6). Thus, ACRBP-V5 plays the key role in the formation and configuration of the acrosomal granule into the center of the acrosomal vesicle during early spermiogenesis. ACRBP-W also seems to partially contribute to the acrosomal granule formation. However, because ACRBP-W is immediately processed into ACRBP-C in spermatids (18), the major role of ACRBP-W is the retention of the inactive status of proACR in the acrosome through the ACRBP-C function, in addition to the promotion of ACR release from the acrosome during acrosomal exocytosis (14, 18), as described in Fig. 7 and Fig. S1.

Fig. 7.

Functional roles of mouse ACRBP in spermiogenesis and fertilization. ACRBP-V5 functions in the formation and configuration of an acrosomal granule in round spermatids (Upper). Because ACRBP-V5 is proteolytically degraded in elongating spermatids (18), this protein may be also involved in the enlargement/elongation of the acrosomal granule. ACRBP-W is synthesized in haploid spermatids and then immediately converted into ACRBP-C by removal of the N-terminal half (18). The major function of ACRBP-W and ACRBP-C is to retain the inactive status of proACR in the acrosomal granule, although ACRBP-W partially contributes to the assembly of acrosomal proteins, including proACR, to form an acrosomal granule. In the fertilization process (Lower), sperm contain only ACRBP-C that promotes ACR release from the acrosome during acrosomal exocytosis. Acrosomal components, including ACRBP-C, are probably degraded by enzymatically active ACR that is released. AG, acrosomal granule; AV, acrosomal vesicle; GA, Golgi apparatus; PS; perivitelline space; ZP, zona pellucida.

Deletions and mutations in some human genes, including SPATA16, PICK1, DPY19L2, and ZPBP1, have been identified in globozoospermia patients (33–38). Gene-knockout mice, including ZPBP1-null (23), SPACA1-null (24), and GOPC-null mice (25), are known to exhibit the phenotype similar to that of human globozoospermia (39–47). Our data indicate that a small population (∼4%) of Acrbp−/− epididymal sperm are round-headed but still possess the fragmented acrosome on the head (Fig. 4), thus suggesting that ACRBP may not be directly involved in the globozoospermia-related phenotype. Of the mutant mice relating to globozoospermia, the acrosome is completely deficient in the Gopc−/− mice (25). As described above, Zpbp1−/− mice exhibit the eccentric localization of the acrosomal granule in spermatids (23), whereas early spermatids of Spaca1−/− mice apparently lack the acrosomal granule in the acrosome (24). The phenotypes of Zpbp1−/− and Spaca1−/− spermatids resemble those of KOW-TG and Acrbp−/− spermatids, respectively. However, the abnormally developing acrosome is gradually lost from the Zpbp1−/− and Spaca1−/− spermatids at later stages of spermiogenesis (23, 24). The levels of ZPBP1 and SPACA1 are significantly low in the Gopc−/− testis (24). Despite a normal level of ZPBP1 in the Spaca1−/− testis, the Zpbp1−/− testis exhibits a greatly reduced level of SPACA1 (24). Importantly, the Acrbp−/− testis normally contains globozoospermia-related proteins, including GOPC, ZPBP1, and SPACA1 (Fig. S3). Thus, the reason why Acrbp−/− spermatids and epididymal sperm still contain the fragmented acrosome may be due to the fact that ACRBP is localized exclusively in the acrosomal matrix, together with proACR (5). Because ZPBP1 and SPACA1 are an inner acrosomal membrane-associated protein and an integral acrosomal membrane protein, respectively (23, 24), it appears that the functional role of ACRBP may be spatiotemporally different from those of GOPC, ZPBP1, and SPACA1 during acrosome formation. We note that the loss of functional ACRBP in human globozoospermia and teratozoospermia patients still remains an open question. Thus, it is important to evaluate the gene mutations in the future.

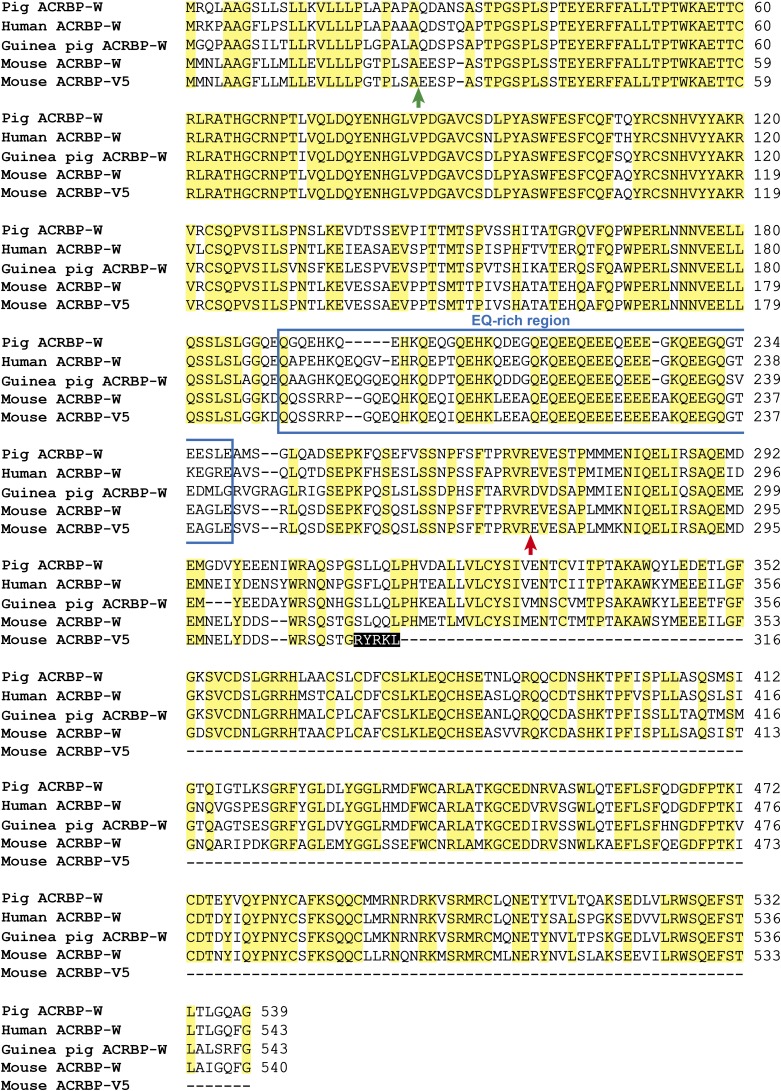

The phenotype of KOW-TG mice is also similar to that of proprotein covertase subtilisin/kexin type 4 (PCSK4; also known as PC4 or SPC5)-null mice (48): the abnormally eccentric localization of the acrosomal granule and the fragmented structure of acrosome. The loss of PCSK4 results in the failure of ACRBP-W proteolytic processing into the mature ACRBP-C in testicular and epididymal sperm (48), implying that the failure of ACRBP-W processing in Pcsk4−/− spermatids may be attributed to abnormal formation of the acrosome. However, despite the phenotypical similarity between the Pcsk4−/− and KOW-TG mice, exogenously expressed ACRBP-W in spermatids and sperm is normally converted into ACRBP-C (Figs. 5 and 6). These results suggest that the ACRBP-W processing, which is presumably catalyzed by PCSK4 directly or indirectly (48), may not be involved in the observed phenotypes of Pcsk4−/− and KOW-TG mice. On the other hand, the concentric localization of acrosomal granule is recovered only by transgenic expression of ACRBP-V5 in Acrbp−/− spermatids (Fig. 6). As described previously (18), ACRBP-V5 is present in the acrosomal granules of round spermatids and then is proteolytically degraded in elongating spermatids. Thus, our present data suggest a possible involvement of ACRBP-V5 in the enlargement/elongation of the acrosomal granule in the acrosome of elongating spermatids; the retention of acrosomal proteins in the acrosomal granule may be released by the disappearance of ACRBP-V5. Indeed, the time period for the appearance and disappearance of ACRBP-V5 matches well with that for the dynamic changes in the structure of acrosomal granule (Fig. 2). Moreover, because the protein sequence of ACRBP-V5 is distinguished from that of ACRBP-W by only five amino acids at the C terminus (Fig. S9), the 5-residue sequence probably acts as the key determinant of the ACRBP-V5 function. How ACRBP-V5 is degraded by proteolytic enzymes, including PCSK4, in spermatids remains to be answered.

Fig. S9.

Sequence alignment of ACRBP-W between mouse and other mammalian species. Mouse ACRBP-V5 is also compared with pig, human, guinea pig, and mouse ACRBP-Ws. The ACRBP proteins contain the region rich in E and Q (blue box). Letters on black- and yellow-background boxes indicate five amino acids in the C terminus of ACRBP-V5 sequence and identical amino acids among five proteins, respectively. The locations of putative cleavage sites for the N-terminal signal peptide and the conversion of ACRBP-W into ACRBP-C are indicated by green and red arrows, respectively. Dashes represent gaps introduced to optimize the sequence alignment.

We (14, 18) previously demonstrated that, although two transcripts encoding ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 are generated in the mouse testis, the pig and guinea pig testes produce only a single mRNA coding for ACRBP-W. A single ACRBP-W mRNA is also transcribed in the human testis (15). Our preliminary experiments indicated that Acrbp-V5 mRNA, in addition to Acrbp-W mRNA, is produced specifically in rodent animals, including rat and hamster. One of the most puzzling questions is whether the single ACRBP-W protein in human, pig, and guinea pig serves the functions of both ACRBP-W and ACRBP-V5 in the mouse. The amino acid sequence of mouse ACRBP-W shares 71–75% identity with those of the human, pig, and guinea pig proteins, whereas the sequence identity of ACRBP-W is around 80% among the three nonrodent animals (Fig. S9). It is thus conceivable that the functional diversity of ACRBP-W is not merely explained by the sequence alignment. Meanwhile, rodent animal sperm usually possess a falciform-shaped head, whereas the heads of pig, guinea pig, and human sperm are spatulate (1, 2). The morphological variation of the sperm heads between rodent and nonrodent animals presumably reflects the difference in the enlargement/elongation of the acrosomal granule in the acrosomal vesicle. If so, ACRBP-V5 may not be essential for the acrosome formation in nonrodent animals. Another possibility is that the time for ACRBP-W conversion into ACRBP-C differs between rodent and nonrodent animals. Although ACRBP-W is immediately processed into ACRBP-C in early spermatids in the mouse (18), the proteolytic processing may occur at later stages of spermiogenesis or during epididymal sperm maturation in the nonrodent animals. In this case, the lack of ACRBP-V5 in nonrodent animals can be compensated by the unprocessed form of ACRBP-W. To explore these possibilities, further studies are required. At any rate, our present study provides an example of cell organellar biogenesis regulated by pre-mRNA alternative splicing.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Mutant Mice Lacking ACRBP.

A targeting vector containing an expression cassette (49) of neo flanked by ∼1.3- and 6.5-kbp genomic regions of Acrbp at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively, was constructed as described previously (50). The MC1 promoter-driven herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene (tk) was also inserted into the 6.5-kbp Acrbp genomic region at the 3′-end. Following electroporation of the targeting vector, which had been linearized by digestion with NotI, into mouse D3 ES cells, homologous recombinants were selected using G418 and gancyclovir as described previously (50). Five ES cell clones carrying the targeted mutation were selected and injected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice (Japan SLC). The blastocysts were transferred to pseudopregnant foster mothers to obtain chimeric male mice. The male mice were crossed to ICR (Institute of Cancer Research)-strain females (Japan SLC) to establish mouse lines heterozygous for the Acrbp mutation. The homozygous mice were obtained by mating of the heterozygous males and females. All animal experiments were performed ethically, and experimentation was in accord with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at University of Tsukuba.

Establishment of Transgenic Mouse Lines Expressing Exogenous ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5.

The 500-bp 5′-flanking region of Acrbp was amplified by PCR, and the DNA fragment was ligated to the cDNA fragment encoding ACRBP-W or ACRBP-V5. The ACRBP-W construct was also designed to fuse with a linker, Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly (51), and EGFP at the C terminus. These two transgene constructs were introduced into appropriate restriction endonuclease sites of pcDNA3.1-myc-His (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and digested with restriction enzymes. The linearized DNA fragments were then microinjected into pronuclei of one-cell embryos from BDF1 mice (Japan SLC) to establish transgenic mouse lines, as described previously (52). Transmission of the transgenes in founder mouse lines was validated by PCR of tail DNAs using a set of two oligonucleotide primers (primer A: 5′-TCAGAGCCCAAGTTTCAATC-3′; primer B: 5′-TAGAAGGCACAGTCGAGG-3′). The founder mice were bred with ICR mice to establish stable transgenic lines that were maintained by mating with ICR mice.

Hybridization Analysis.

Genomic DNA was prepared from mouse tail, digested by BamHI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). Total cellular RNAs were extracted from testicular tissues using Isogen (Nippon Gene) as described previously (53). The RNA samples were glyoxylated, separated by electrophoresis on agarose gels, and transferred onto nylon membranes. Hybridization was carried out as described previously (53).

Preparation of Protein Extracts.

Testicular tissues of mice (3–5 mo old) were homogenized at 4 °C in a lysis buffer, pH 7.4, consisting of 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 0.15 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 75 U/mL aprotinin, using a Potter-Elvehjem glass homogenizer (AS ONE Co.) fitted with a Teflon pestle (10 strokes). Cauda epididymal sperm were lysed in the same lysis buffer by pipetting at 4 °C. The homogenates were centrifuged at 11,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant solution was used as a source of protein extracts. Protein concentration was determined using a Coomassie protein assay reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antibodies.

His-tagged recombinant ZPBP1 and ZPBP2 containing the amino acid sequences at positions 101–406 and 22–253, respectively, were produced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3), as described previously (18, 23). The recombinant proteins were purified on a Ni-NTA His column (Merck Millipore), emulsified with Freund’s complete (Becton Dickenson) or incomplete adjuvant (Wako), and injected into female New Zealand White rabbits (SLC). Antibodies were affinity-purified on Sepharose 4B columns previously coupled with GST-tagged recombinant ZPBP1 and ZPBP2 as described previously (18). Polyclonal antibodies against ACRBP-C, ACRBP-V5, ACR, SPAM1, HYAL5, ADAM3, IZUMO1, and SPACA1 were prepared as described previously (10, 18, 24, 27, 28, 54, 55). Anti-ACTB (clone AC-15) and anti-TUBB1 (clone 2-28-33) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-His-Tag, anti-GOPC/PIST, anti-HRB/AGFG1, anti-PRSS21/TESP5, and anti-Myc (clone 9E10) antibodies were the products of Medical and Biological Laboratories, Abcam, Proteintech, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and ThermoFisher Scientific, respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies against rabbit, mouse, or goat IgG (H + L) were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibodies against rabbit or mouse IgG were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred onto Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Merck Millipore). The blots were blocked with 4% (wt/vol) skim milk in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 0.15 M NaCl at room temperature for 1 h, incubated with primary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h, and then treated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase at room temperature for 1 h. The immunoreactive proteins were visualized by using an ECL Western Blotting Detection kit (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences), followed by exposure to X-ray films (Fujifilm).

Immunostaining Analysis.

Cauda epididymal sperm were dispersed in a 0.2-mL drop of TYH (Toyoda–Yokoyama–Hoshi) medium (56) free of BSA. The sperm suspension was transferred into a 1.5-mL microtube, washed with PBS by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min, fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2, on ice for 15 min, washed with cold PBS, and then treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 15 min. The fixed cells were blocked with 3% (vol/vol) normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 on ice for 30 min, washed with the same buffer, incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h, washed, and then reacted with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit or mouse IgG antibody for 1 h. After washing with PBS, sperm cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated PNA (3 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Hoechst 33342 (2.5 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min, washed with PBS, mounted, and then observed under an IX-71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus), as described previously (57). Spermatogenic cells were prepared from seminiferous tubules as described previously (58). After blocking with 3% (vol/vol) normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, the cell samples were treated with primary antibodies, reacted with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit or mouse IgG antibody, incubated with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled PNA and Hoechst 33342, and then observed, as described above.

TEM Analysis.

Fresh tissues of cauda epididymides and testes were fixed in 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, for 30 min at room temperature, washed with PB, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 30 min at 4 °C, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections (90 nm) were prepared by using a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome (Reichert Technologies, Inc.), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and then observed under a JEM1400 TEM (JEOL) at 80-kV accelerating voltage.

CASA.

Parameters of sperm motility were quantified by CASA using an integrated visual optical system (IVOS) software (Hamilton-Thorne Biosciences) as described previously (59). Briefly, cauda epididymal sperm were capacitated by incubation for 2 h in a 0.1-mL drop of TYH medium at 37 °C under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. An aliquot of the capacitated sperm suspension was transferred into a prewarmed counting chamber (depth = 20 μm), and more than 200 sperm were examined for each sample using standard settings (30 frames acquired at a frame rate of 60 Hz at 37 °C) as described previously (60, 61). Hyperactivated motility of sperm was determined by using the SORT function of the IVOS software (61). Sperm were classified as “hyperactivated” when the trajectory met the following criteria (61): curvilinear velocity ≥ 180 μm/s, linearity ≤ 38%, and amplitude of lateral head displacement ≥ 9.5 μm.

IVF Assays.

ICR mice (8–10 wk old) were superovulated by intraperitoneal injection of pregnant mare’s serum gonadotropin (5 units; Aska Pharmaceutical Co.) followed by human CG (hCG) (5 units; Aska Pharmaceutical) 48 h later. The cumulus-intact metaphase II-arrested oocytes were isolated from the oviductal ampulla of superovulated mice 14 h after hCG injection and placed in a 90-μL drop of TYH medium. Cauda epididymal sperm were capacitated by incubation in a 0.1-mL drop of TYH medium for 2 h at 37 °C under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. An aliquot (1.5 × 104 cells/10 μL) of the capacitated sperm suspension was mixed with the above-mentioned 90-μL drop of TYH medium containing the oocytes to give a final concentration of 1.5 × 102 sperm/μL. The mixture (0.1 mL) was incubated for 6 h at 37 °C under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. The fertilized oocytes were treated with bovine testicular hyaluronidase (350 units/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min to remove cumulus cells, fixed in PBS containing 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and washed with PBS containing 0.5% PVP. The female and male pronuclei in the fertilized oocytes were stained with Hoechst 33342 (2.5 μg/mL) and then viewed under an IX-71 fluorescence microscope as described previously (59).

Sperm/ZP-Binding Assays.

The cumulus-free, ZP-intact oocytes were prepared by treatment with bovine testicular hyaluronidase for 15 min, washed with TYH medium, and placed in a 90-μL drop of TYH medium. Capacitated epididymal sperm (3.0 × 104 cells/10 μL) were mixed with the 90-μL drop containing the cumulus-free oocytes and two-cell embryos, and the mixture (0.1 mL) was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. The oocytes were transferred to a 0.1-mL drop of TYH medium, washed by pipetting to remove loosely bound and unbound sperm, fixed in PBS containing 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and 0.5% PVP for 15 min, and washed with PBS containing 0.5% PVP. After staining with Hoechst 33342 (2.5 μg/mL), the numbers of sperm tightly bound to the ZP were counted under an Olympus IX-71 fluorescence microscope, as described previously (59). The two-cell embryos were used as an internal negative control for nonspecific and loose sperm binding.

Sperm/Oocyte Fusion Assays.

The cumulus-free, ZP-intact oocytes were treated with acid Tyrode (Sigma-Aldrich), washed with TYH medium, treated with Hoechst 33342 (2.5 μg/mL) for 10 min, and washed three times with TYH medium as described previously (59). The Hoechst-labeled, ZP-free oocytes in a 90-μL drop of TYH medium were mixed with capacitated epididymal sperm (1.5 × 104 cells/10 μL), and the mixture (0.1 mL) was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. The oocytes were washed with PBS containing 0.5% PVP, fixed in PBS containing 0.25% glutaraldehyde and 0.5% PVP, and then observed under an Olympus IX-71 fluorescence microscope.

ICSI.

ICSI was carried out according to the already published procedure (62), using a micropipette attached to a Piezo-electric actuator (PrimeTech). Briefly, a single epididymal sperm was sucked into an injection pipette, and the sperm head was separated from the tail by applying a few Piezo pulses to the head–tail junction. The cumulus-free oocytes were prepared from superovulated BDF1 mice (Japan SLC) as described above. The sperm head was injected into the oocyte in Hepes-buffered CZB (Chatot–Ziomek–Bavister) medium (63). Type 4 Acrbp−/− sperm, the head and tail of which could not be separated by Piezo pulses, were injected into the oocyte as the whole cell. The injected oocytes were cultured in CZB medium at 37 °C for 24 h under 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in air. Embryos that reached the two-cell stage were transferred into the oviducts of pseudopregnant ICR mice on the day after sterile mating with a vasectomized male (day 0.5). On day 19.5, the uteri of the recipient mice were examined for the presence of live term fetuses.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are represented as the mean ± SE (n ≥ 3). The Student t test was used for statistical analysis; significance was assumed for P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NPO Biotechnology Research and Development for generation of mutant mice, and Ms. J. Sakamoto for transmission electron microscope analysis. This work was supported in part by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (to Y. Kanemori and T.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522333113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Leblond CP, Clermont Y. Spermiogenesis of rat, mouse, hamster and guinea pig as revealed by the periodic acid-fuchsin sulfurous acid technique. Am J Anat. 1952;90(2):167–215. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yanagimachi R. Mammalian fertilization. In: Kobil E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol 1. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 189–317. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abou-Haila A, Tulsiani DR. Mammalian sperm acrosome: Formation, contents, and function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;379(2):173–182. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL. The acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex and the shaping of the spermatid head. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67(4):271–284. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buffone MG, Foster JA, Gerton GL. The role of the acrosomal matrix in fertilization. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52(5-6):511–522. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072532mb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okabe M. The cell biology of mammalian fertilization. Development. 2013;140(22):4471–4479. doi: 10.1242/dev.090613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KS, Gerton GL. Differential release of soluble and matrix components: Evidence for intermediate states of secretion during spontaneous acrosomal exocytosis in mouse sperm. Dev Biol. 2003;264(1):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baba T, Azuma S, Kashiwabara S, Toyoda Y. Sperm from mice carrying a targeted mutation of the acrosin gene can penetrate the oocyte zona pellucida and effect fertilization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(50):31845–31849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagata K, et al. Acrosin accelerates the dispersal of sperm acrosomal proteins during acrosome reaction. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(17):10470–10474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue N, Ikawa M, Isotani A, Okabe M. The immunoglobulin superfamily protein Izumo is required for sperm to fuse with eggs. Nature. 2005;434(7030):234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bianchi E, Doe B, Goulding D, Wright GJ. Juno is the egg Izumo receptor and is essential for mammalian fertilization. Nature. 2014;508(7497):483–487. doi: 10.1038/nature13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baba T, Michikawa Y, Kashiwabara S, Arai Y. Proacrosin activation in the presence of a 32-kDa protein from boar spermatozoa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160(3):1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy DM, Oda MN, Friend DS, Huang TT., Jr A mechanism for differential release of acrosomal enzymes during the acrosome reaction. Biochem J. 1991;275(Pt 3):759–766. doi: 10.1042/bj2750759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baba T, et al. An acrosomal protein, sp32, in mammalian sperm is a binding protein specific for two proacrosins and an acrosin intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(13):10133–10140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ono T, et al. Identification of proacrosin binding protein sp32 precursor as a human cancer/testis antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(6):3282–3287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041625098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tammela J, et al. OY-TES-1 expression and serum immunoreactivity in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2006;29(4):903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehurst AW, et al. Tumor antigen acrosin binding protein normalizes mitotic spindle function to promote cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(19):7652–7661. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanemori Y, et al. Two functional forms of ACRBP/sp32 are produced by pre-mRNA alternative splicing in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2013;88(4):105. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.107425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortimer D, Curtis EF, Miller RG. Specific labelling by peanut agglutinin of the outer acrosomal membrane of the human spermatozoon. J Reprod Fertil. 1987;81(1):127–135. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0810127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell LD, Ettlin RA, Sinha Hikim AP, Clegg ED. Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis. Cache River Press; Clearwater, FL: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roqueta-Rivera M, Abbott TL, Sivaguru M, Hess RA, Nakamura MT. Deficiency in the omega-3 fatty acid pathway results in failure of acrosome biogenesis in mice. Biol Reprod. 2011;85(4):721–732. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.089524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito C, et al. Integration of the mouse sperm fertilization-related protein equatorin into the acrosome during spermatogenesis as revealed by super-resolution and immunoelectron microscopy. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;352(3):739–750. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1605-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YN, Roy A, Yan W, Burns KH, Matzuk MM. Loss of zona pellucida binding proteins in the acrosomal matrix disrupts acrosome biogenesis and sperm morphogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(19):6794–6805. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01029-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujihara Y, et al. SPACA1-deficient male mice are infertile with abnormally shaped sperm heads reminiscent of globozoospermia. Development. 2012;139(19):3583–3589. doi: 10.1242/dev.081778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao R, et al. Lack of acrosome formation in mice lacking a Golgi protein, GOPC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(17):11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162027899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamsadin R, et al. Male mice deficient for germ-cell cyritestin are infertile. Biol Reprod. 1999;61(6):1445–1451. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.6.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baba D, et al. Mouse sperm lacking cell surface hyaluronidase PH-20 can pass through the layer of cumulus cells and fertilize the egg. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(33):30310–30314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim E, et al. Identification of a hyaluronidase, Hyal5, involved in penetration of mouse sperm through cumulus mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(50):18028–18033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506825102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honda A, Yamagata K, Sugiura S, Watanabe K, Baba T. A mouse serine protease TESP5 is selectively included into lipid rafts of sperm membrane presumably as a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(19):16976–16984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyata H, et al. Sperm calcineurin inhibition prevents mouse fertility with implications for male contraceptive. Science. 2015;350(6259):442–445. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ. The biology of infertility: Research advances and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1197–1213. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrin A, et al. Molecular cytogenetic and genetic aspects of globozoospermia: A review. Andrologia. 2013;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2012.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dam AHDM, et al. Homozygous mutation in SPATA16 is associated with male infertility in human globozoospermia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(4):813–820. doi: 10.1086/521314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu G, Shi Q-W, Lu G-X. A newly discovered mutation in PICK1 in a human with globozoospermia. Asian J Androl. 2010;12(4):556–560. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elinati E, et al. Globozoospermia is mainly due to DPY19L2 deletion via non-allelic homologous recombination involving two recombination hotspots. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(16):3695–3702. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coutton C, et al. MLPA and sequence analysis of DPY19L2 reveals point mutations causing globozoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2549–2558. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yatsenko AN, et al. Association of mutations in the zona pellucida binding protein 1 (ZPBP1) gene with abnormal sperm head morphology in infertile men. Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18(1):14–21. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu F, Gong F, Lin G, Lu G. DPY19L2 gene mutations are a major cause of globozoospermia: Identification of three novel point mutations. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013;19(6):395–404. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu X, Toselli PA, Russell LD, Seldin DC. Globozoospermia in mice lacking the casein kinase II alpha′ catalytic subunit. Nat Genet. 1999;23(1):118–121. doi: 10.1038/12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang-Decker N, Mantchev GT, Juneja SC, McNiven MA, van Deursen JM. Lack of acrosome formation in Hrb-deficient mice. Science. 2001;294(5546):1531–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1063665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yildiz Y, et al. Mutation of beta-glucosidase 2 causes glycolipid storage disease and impaired male fertility. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(11):2985–2994. doi: 10.1172/JCI29224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao N, et al. PICK1 deficiency causes male infertility in mice by disrupting acrosome formation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(4):802–812. doi: 10.1172/JCI36230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lerer-Goldshtein T, et al. TMF/ARA160: A key regulator of sperm development. Dev Biol. 2010;348(1):12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paiardi C, Pasini ME, Gioria M, Berruti G. Failure of acrosome formation and globozoospermia in the wobbler mouse, a Vps54 spontaneous recessive mutant. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1(1):52–62. doi: 10.4161/spmg.1.1.14698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Audouard C, Christians E. Hsp90β1 knockout targeted to male germline: A mouse model for globozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(4):1475–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierre V, et al. Absence of Dpy19l2, a new inner nuclear membrane protein, causes globozoospermia in mice by preventing the anchoring of the acrosome to the nucleus. Development. 2012;139(16):2955–2965. doi: 10.1242/dev.077982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, et al. Atg7 is required for acrosome biogenesis during spermatogenesis in mice. Cell Res. 2014;24(7):852–869. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tardif S, Guyonnet B, Cormier N, Cornwall GA. Alteration in the processing of the ACRBP/sp32 protein and sperm head/acrosome malformations in proprotein convertase 4 (PCSK4) null mice. Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18(6):298–307. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tybulewicz VL, Crawford CE, Jackson PK, Bronson RT, Mulligan RC. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell. 1991;65(7):1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kashiwabara S, et al. Regulation of spermatogenesis by testis-specific, cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase TPAP. Science. 2002;298(5600):1999–2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1074632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagai T, Sawano A, Park ES, Miyawaki A. Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(6):3197–3202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051636098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407(3):313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kashiwabara S, et al. Identification of a novel isoform of poly(A) polymerase, TPAP, specifically present in the cytoplasm of spermatogenic cells. Dev Biol. 2000;228(1):106–115. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamagata K, Honda A, Kashiwabara SI, Baba T. Difference of acrosomal serine protease system between mouse and other rodent sperm. Dev Genet. 1999;25(2):115–122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)25:2<115::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishimura H, Kim E, Nakanishi T, Baba T. Possible function of the ADAM1a/ADAM2 Fertilin complex in the appearance of ADAM3 on the sperm surface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(33):34957–34962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toyoda Y, Yokoyama M, Hoshi T. Studies on fertilization of mouse eggs in vitro. Jpn J Anim Reprod. 1971;16(4):147–151. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamazaki T, Yamagata K, Baba T. Time-lapse and retrospective analysis of DNA methylation in mouse preimplantation embryos by live cell imaging. Dev Biol. 2007;304(1):409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kotaja N, et al. Preparation, isolation and characterization of stage-specific spermatogenic cells for cellular and molecular analysis. Nat Methods. 2004;1(3):249–254. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1204-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawano N, et al. Mice lacking two sperm serine proteases, ACR and PRSS21, are subfertile, but the mutant sperm are infertile in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2010;83(3):359–369. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.083089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mortimer ST. CASA: Practical aspects. J Androl. 2000;21(4):515–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bray C, Son J-H, Kumar P, Meizel S. Mice deficient in CHRNA7, a subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, produce sperm with impaired motility. Biol Reprod. 2005;73(4):807–814. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.042184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ogonuki N, et al. The effect on intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome of genotype, male germ cell stage and freeze-thawing in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chatot CL, Ziomek CA, Bavister BD, Lewis JL, Torres I. An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1989;86(2):679–688. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0860679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.