Significance

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) is a deadly tick-borne viral pathogen. Since first being reported in China in 2009, SFTSV has spread throughout South Korea and Japan, with mortality rates reaching up to 30%. The surface of the SFTSV virion is decorated by two glycoproteins, Gn and Gc. Here, we report the atomic-level structure of the Gc glycoprotein in a conformation formed during uptake of the virion into the host cell. Our analysis reveals the conformational changes that the Gc undergoes during host cell infection and provides structural evidence that these rearrangements are conserved with otherwise unrelated alpha- and flaviviruses.

Keywords: emerging virus, phlebovirus, viral membrane fusion, bunyavirus, structure

Abstract

An emergent viral pathogen termed severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) is responsible for thousands of clinical cases and associated fatalities in China, Japan, and South Korea. Akin to other phleboviruses, SFTSV relies on a viral glycoprotein, Gc, to catalyze the merger of endosomal host and viral membranes during cell entry. Here, we describe the postfusion structure of SFTSV Gc, revealing that the molecular transformations the phleboviral Gc undergoes upon host cell entry are conserved with otherwise unrelated alpha- and flaviviruses. By comparison of SFTSV Gc with that of the prefusion structure of the related Rift Valley fever virus, we show that these changes involve refolding of the protein into a trimeric state. Reverse genetics and rescue of site-directed histidine mutants enabled localization of histidines likely to be important for triggering this pH-dependent process. These data provide structural and functional evidence that the mechanism of phlebovirus–host cell fusion is conserved among genetically and patho-physiologically distinct viral pathogens.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV; also known as Huaiyangshan virus) constitutes one of the most dangerous human pathogens within the Phlebovirus genus of the Bunyaviridae family. Since emerging in China in 2009, thousands of infections have been reported in humans throughout China, South Korea, and Japan. Upon zoonosis from ticks to humans, SFTSV causes thrombocytopenia, leukocytopenia, febrile illness, and in severe cases encephalitis (1–3). SFTSV belongs to the Bhanja phlebovirus serocomplex, and genomic analysis reveals that the virus has evolved extensively over the last 150 y, having diverged into at least five different clusters (4). Although a recent study suggested that many SFTSV infections are subclinical (5), mortality rates reach up to 30% in a clinical setting (1) and there are currently no vaccines or antivirals against the virus.

The negative-sense and single-stranded genome of SFTSV is divided into three RNA segments: S, M, and L. The M segment encodes two glycoproteins, Gn and Gc, which facilitate host cell entry and are derived by cleavage of a polyprotein precursor by cellular proteases during translation (6). Similar to related phleboviruses, Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) and Uukuniemi virus (UUKV), SFTSV Gn and Gc likely form higher order pentamers and hexamers on the virion envelope in an icosahedral T = 12 symmetry (7–10). The N-linked glycans displayed by this glycoprotein complex are important determinants of tissue and receptor tropism and are recognized by the C-type lectin host cell receptor, DC-SIGN, during viral attachment (11, 12). Following receptor recognition, the virion is endocytosed into the host cell (13–15), and the metastable Gc orchestrates fusion of endosomal and viral membranes, facilitating release of viral RNA into the cytosol. Interestingly, SFTSV is also capable of cell entry via extracellular vesicles, which likely allows evasion of the host immune system (16). Structural studies of the cognate Gc from RVFV (17) in the prefusion conformation revealed that the phleboviral Gc forms a class II architecture, which has been also observed for envelope glycoproteins from positive-sense RNA viruses from the Togaviridae and Flaviridae families (18, 19). A similar class II architecture has also been observed in cell–cell fusion proteins, although the mechanism of membrane fusion is likely to differ from viral fusion as evident by the absence of a hydrophobic fusion loop (20).

A detailed mechanism of membrane fusion by class II viral fusion proteins has been proposed, where pH-dependent triggering of the glycoprotein is thought to arise during endosomal trafficking of the virus (21–23). It is expected that the acidic environment within endocytotic compartments activates a “histidine switch,” which disrupts protein–protein contacts on the virion surface such that hydrophobic residues located at the apex of the molecule are exposed and extended into the target host membrane. Upon membrane binding, togaviral and flaviviral fusion glycoproteins form trimers (21, 24) that are believed to trigger hemifusion (25, 26). The concerted action of two or more trimers is thought to be required to draw together virion and host cell membranes, in a process ultimately leading to membrane merger (25, 26).

To deepen our understanding of the mechanism of phlebovirus–host cell membrane fusion during host cell infection, we solved the crystal structure of the soluble ectodomain of SFTSV Gc to 2.45-Å resolution. SFTSV Gc crystallized in a three-domain (I–III), trimeric postfusion configuration. By comparison of our SFTSV Gc structure to the prefusion structure of the RVFV Gc, we show that the fusogenic rearrangements of the phleboviral Gc are analogous to those observed for the envelope fusion glycoproteins of alpha- (family Togaviridae) and flaviviruses (family Flaviviridae), indicating a conserved mechanism of membrane fusion between these otherwise nonrelated groups of viruses. Interestingly, we identify two putative fusion loops, which are likely inserted into the host membrane during host cell entry. The conformation of these hydrophobic loops remains unchanged between pre- and postfusion RVFV and SFTSV Gc structures despite exhibiting low sequence conservation. By reverse genetics and rescue of site-directed fusion loop mutants, we show that these residues are stringently required for the virus lifecycle. We also present evidence that histidines in domains I and III of the Gc are essential for the virus life cycle and, by analogy to RVFV (15), likely contribute to the pH-induced conformational rearrangements of the molecule. These data provided structural and functional evidence for a unified mechanism of membrane fusion between phlebo-, flavi-, and alphaviruses.

Results and Discussion

The SFTSV Gc Ectodomain Forms Putative Trimers at Acidic pH.

The ectodomain of SFTSV Gc (residues 563–996, Fig. 1A), lacking 39 residues proximal to the predicted C-terminal transmembrane region, was recombinantly expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells in the presence of the α-mannosidase I inhibitor, kifunensine (27). Soluble SFTSV Gc was purified from cell supernatant, and N-linked glycosylation was cleaved to single acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) moieties with endoglycosidase F1 (28).

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of SFTSV Gc in the postfusion conformation. (A) Domain diagram of the full M segment of SFTSV containing Gn and Gc with the crystallized ectodomain colored by domain: domain I in red, domain II in yellow, and domain III in blue. (B) SFTSV Gc in the postfusion trimeric conformation. The full trimer is shown on Left in cartoon representation and is colored according to domain as in A. Glycans observed in the crystal structure are shown as green sticks. On Right, a single protomer is shown in cartoon representation with the remainder of the trimer shown as a white van der Waals surface.

Similar to that observed for the Gc glycoprotein from the related RVFV Gc (17), SFTSV Gc eluted as a single monomeric species on size exclusion (SEC) at neutral pH (8.0). Upon acidification (5.0), we observed a mixture of monomeric and putative trimeric species, consistent with rearrangements of the molecule to a postfusion state (Fig. S1) (29). These observations are suggestive that an acidic environment is necessary for the formation of SFTSV Gc trimers.

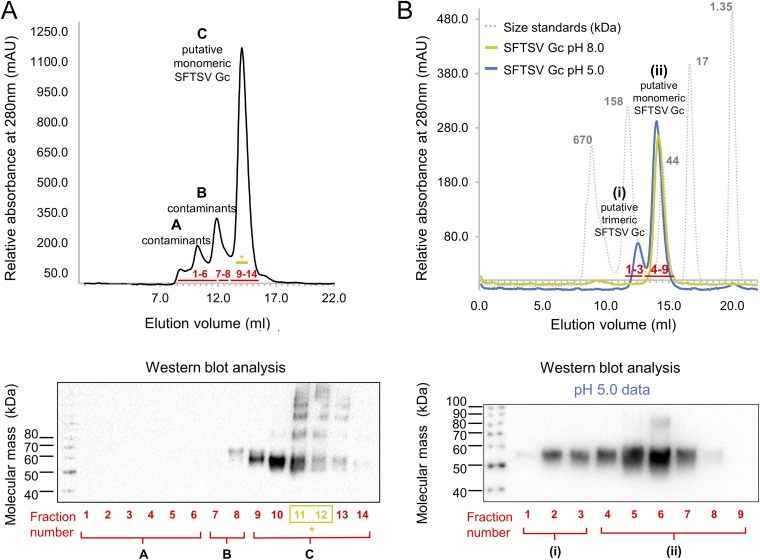

Fig. S1.

Size exclusion (SEC) and Western blot analysis of purified SFTSV Gc. SEC was performed on a Superdex Increase 200 10/30 column (Amersham) equilibrated in 150 mM NaCl and either 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, or 20 mM citrate–NaOH, pH 5.0 (see SI Materials and Methods). (A) SEC of SFTSV Gc run at pH 8.0 following immobilized nickel affinity purification revealed one major peak (peak C) and two minor peaks (peaks A and B). Western blot analysis of fractions confirmed that peaks A and B contained contaminants from recombinant protein expression and peak C contained hexa-histidine–tagged SFTSV Gc. Fractions colored in olive green (*) were pooled and used for further SEC analysis in B. (B) Peak fractions 11 and 12 from SEC performed in A were split in two and run at pH 8.0 and pH 5.0. A gel filtration standard (Bio-Rad, gray) was run on the same column for comparison. At pH 8.0 (green), a single peak (ii) corresponding to putative monomeric SFTSV Gc was observed. At pH 5.0 (blue), a second small peak (i), corresponding to a putative trimer, was observed in addition to peak ii. Western blot analysis of pH 5.0 SEC fractions revealed that both the monomeric (ii) and putative trimeric (i) peaks were composed of SFTSV Gc, indicating that exposure to acidic environments may trigger SFTSV Gc trimerization in solution.

Crystal Structure of SFTSV Gc in the Trimeric Postfusion Conformation.

The structure of SFTSV Gc was solved by the single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) method, with a platinum derivative (K2PtCl6) (Table 1). A single trimer of SFTSV Gc was observed in the asymmetric unit. In line with both our SEC analysis at acidic pH (Fig. S1) and previously reported structures of dengue virus (DENV) E (21) and Semliki Forest virus (SFV) E1 (24) glycoproteins in trimeric states, we suggest that our SFTSV Gc is in a postfusion conformation. Each protomer of the trimer is composed of three domains: I, II, and III (Fig. 1B). Domain I consists of an elongated 13-stranded β-sandwich at the central core of the structure, domain II consists of a five-stranded β-sandwich and a six-stranded β-sheet, and domain III consists of a seven-stranded β-barrel–like module and forms extensive protein–protein contacts (1,321 Å2) with domain I. Overlay analysis reveals little deviation in structure between symmetry-related Gc protomers. The average root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) was 0.64 Å over 428 Cα residues, with the greatest differences detected at regions responsible for forming crystallographic contacts (Fig. S2). Unlike what has been observed for SFV E1 (24), analysis of crystallographic packing did not reveal any physiologically relevant higher order oligomeric arrangements of SFTSV Gc trimers.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement

| Crystallographic parameters | K2PtCl6 SAD data | Native data |

| Data collection | ||

| Beamline | I04, DLS | I03, DLS |

| Resolution range, Å | 108.62–2.89 (2.97–2.89) | 108.51–2.45 (2.51–2.45) |

| Space group | I212121 | I212121 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c, Å | 147.2, 152.3, 160.9 | 147.4, 152.3, 160.4, |

| α, β, γ, ° | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| No. of crystals | 3 | 2 |

| Wavelength, Å | 1.072 | 1.008 |

| Unique reflections | 40,765 (2,964) | 66,293 (4,838) |

| Completeness, % | 99.9 (98.9) | 99.8 (99.3) |

| Rmerge, %* | 16.4 (63.7) | 10.2 (108.4) |

| I/σI | 22.1 (2.6) | 15.7 (1.8) |

| Average redundancy | 34.1 (6.0) | 8.1 (7.8) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution range | 108.51–2.45 (2.51–2.45) | |

| No. of reflections | 66,125 (2,792) | |

| Rwork, %† | 19.0 | |

| Rfree, %‡ | 23.2 | |

| rmsd | ||

| Bonds, Å | 0.002 | |

| Angles, ° | 0.500 | |

| Molecules per a.s.u. | 3 | |

| Atoms per a.s.u. | ||

| protein/carbohydrate/ water | 9,565/42/104 | |

| Average B factors, Å2 | ||

| protein/carbohydrate/ water | 81.3/103.6/62.5 | |

| Ramachandran plot, % | ||

| Most favored region | 96.9 | |

| Allowed region | 3.0 | |

| Outliers | 0.1 |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the relevant outer resolution shell. a.s.u., asymmetric unit; rmsd, root-mean-square deviation from ideal geometry.

Rmerge = Σhkl Σi|I(hkl;i) – <I(hkl)>|/Σhkl ΣiI(hkl;i), where I(hkl;i) is the intensity of an individual measurement and <I(hkl)> is the average intensity from multiple observations.

Rfactor = Σhkl||Fobs| – k|Fcalc||/Σhkl|Fobs|.

Rfree is calculated as for Rwork, but using only 5% of the data that were sequestered before refinement.

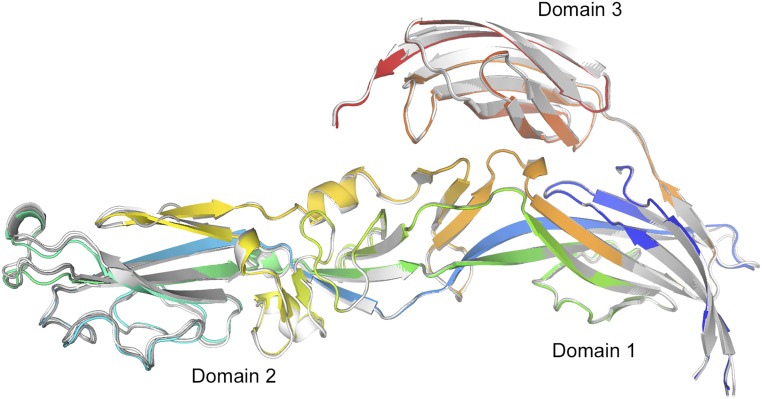

Fig. S2.

Structure and fold of SFTSV Gc protomer. An overlay of the three SFTSV Gc chains observed in the asymmetric unit is shown. One protomer of SFVTSV Gc is shown in cartoon representation and is colored as a rainbow ramped from blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus), and the other two overlaid protomers are shown in gray. The average rmsd is 0.64 Å over 428 Cα residues.

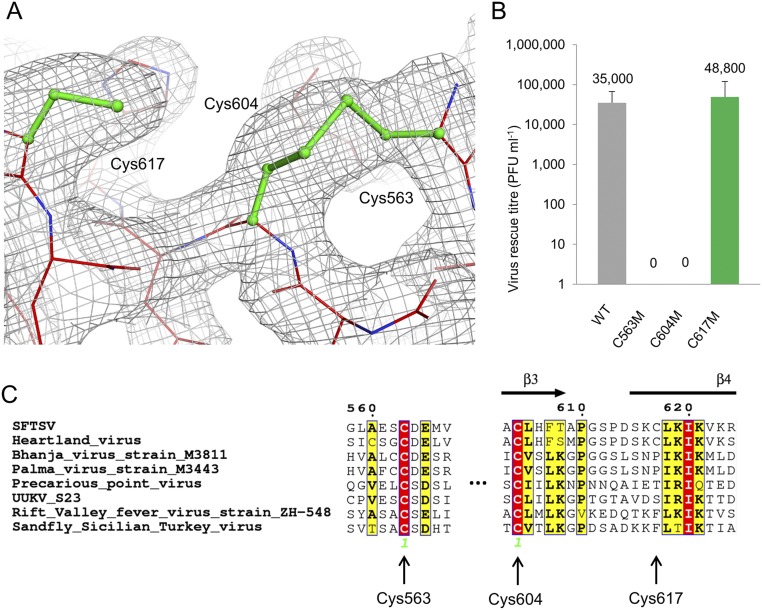

The SFTSV Gc ectodomain is stabilized by 13 disulphide bonds in a pattern that is well-conserved across phleboviruses (Fig. S3). In addition to these disulphide bond pairs, we also observed an unpaired cysteine, Cys617, in domain I of the molecule. Cys617 is solvent exposed and located in close proximity to the Cys563−Cys604 disulphide pairing (Fig. S4). This lone cysteine is present in Heartland phlebovirus Gc, but a phenylalanine (Phe744) is found in the equivalent position in RVFV Gc (Fig. S4). Mutagenesis of the cysteine to methionine (C617M) had no effect upon soluble expression of SFTSV Gc (Fig. S5). Similarly, rescue of live SFTSV further confirmed that this aberrant cysteine has little influence upon virus replication, where the C617M mutant recovered to wild-type levels (Fig. S4).

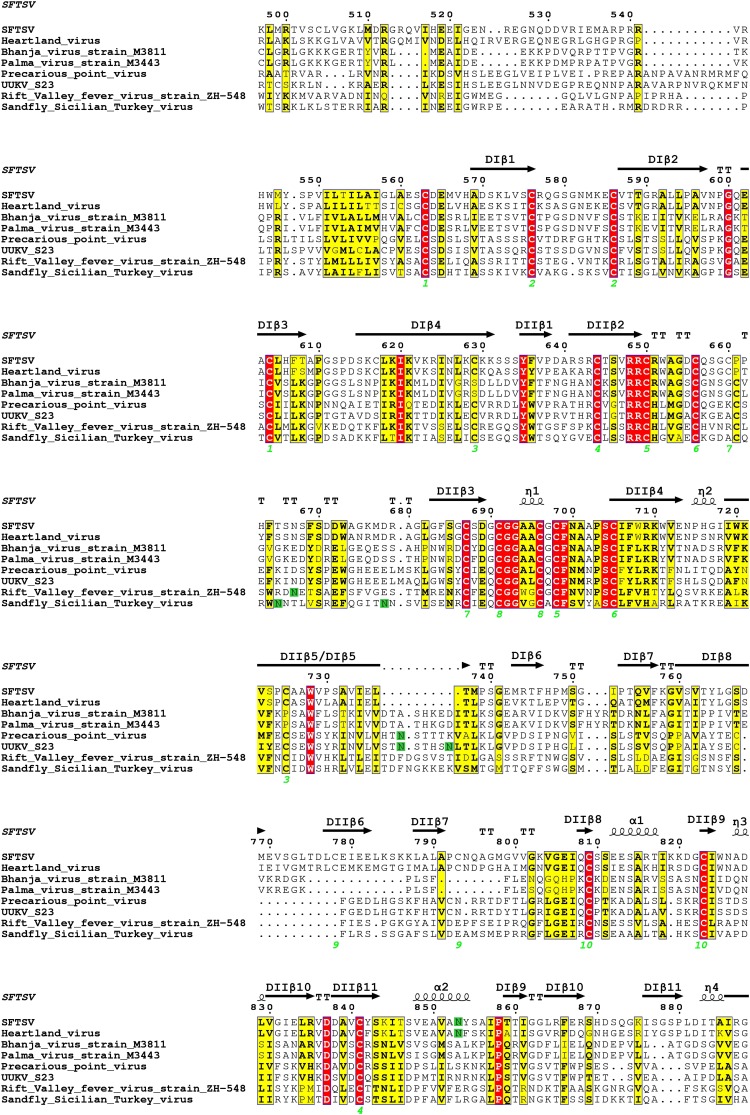

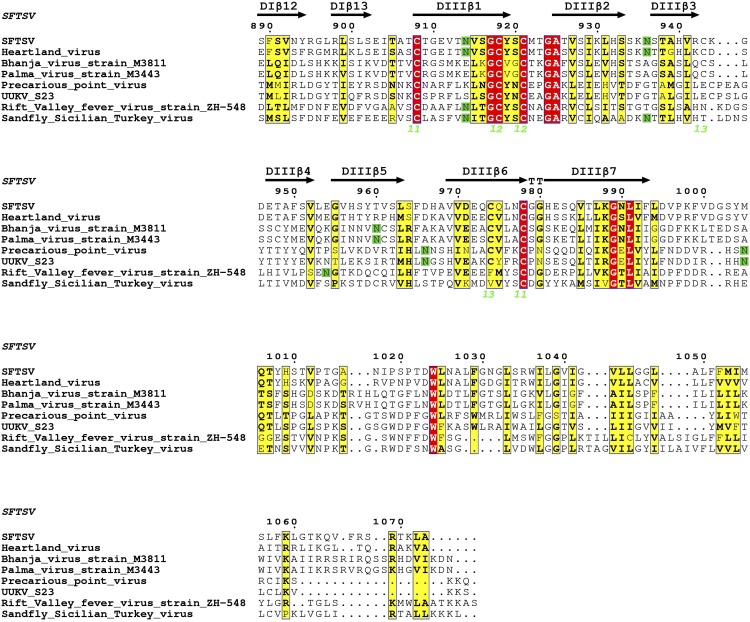

Fig. S3.

Sequence alignment of phleboviral Gc glycoproteins of selected phleboviruses, numbered according to SFTSV. Sequences of eight phleboviral M segments from four distinct clades were chosen and aligned (see Materials and Methods). The alignment numbering is based on SFTSV M segment. Fully conserved residues are shown in red and partially conserved residues in yellow. Residues highlighted green are predicted to be glycosylated; disulfide bonds observed in the SFTSV Gc crystal structure are numbered below the sequence in lime green. Secondary structure elements are labeled above the alignment, with β-strands shown as arrows and with helices (α-helix, α; 310 helix η) shown as spirals.

Fig. S4.

Aberrant Cys617 is found solely in SFTSV and Heartland virus. (A) Electron density (2Fo-Fc contoured at 1.0 σ, gray) around cysteines Cys563, Cys604, and Cys617 in SFTSV Gc. (B) SFTSV encoding single cysteine mutations (C563M, C604M, and C617M) were derived by reverse genetics, and the titers of these recombinant viruses, measured in PFUs, were compared with that of WT SFTSV. Only the C617M mutants were rescued and titrated to levels comparable with the WT virus, whereas C563M and C604M failed to rescue. (C) Sequence alignment of selected phleboviruses (colored and annotated as in Fig. S3) reveals that Cys563 and Cys604 are conserved among all selected phleboviruses, but Cys617 is only found in the closely related Heartland virus.

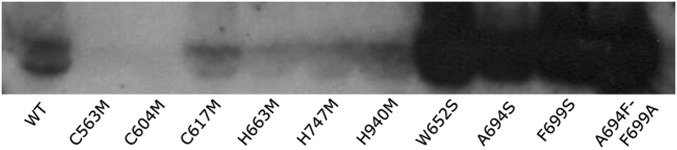

Fig. S5.

Western blot analysis confirms the secreted and soluble expression of SFTSV Gc ectodomain mutants in mammalian HEK 293T cells (see SI Materials and Methods). The WT SFTSV Gc ectodomain construct crystallized in this manuscript was used as a control. Two mutants, C563M and C604M, were not secreted and folded. All other mutants were expressed at levels equivalent to or greater than WT. Fusion loop mutants W652S, A694S, F966S, and A694F-F699A exhibited a greater level of overall expression with respect to WT, which may possibly be attributed to the increased protein stability achieved by the removal of solvent-exposed hydrophobic amino acids in the putative fusion loops.

We note that in addition to this free cysteine being present in several species of SFTSV, it is also observed in the related Heartland phlebovirus (Fig. S3). Indeed, unpaired cysteines, with no obvious functional roles, have also been observed in other virus families. For example, such a free cysteine motif has been observed on the attachment glycoprotein of an African henipavirus (30).

Rearrangements of Gc Are Conserved with Flavi- and Alphaviruses.

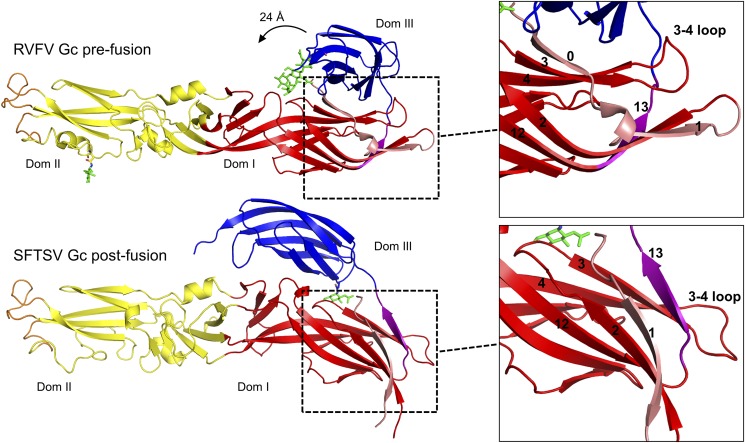

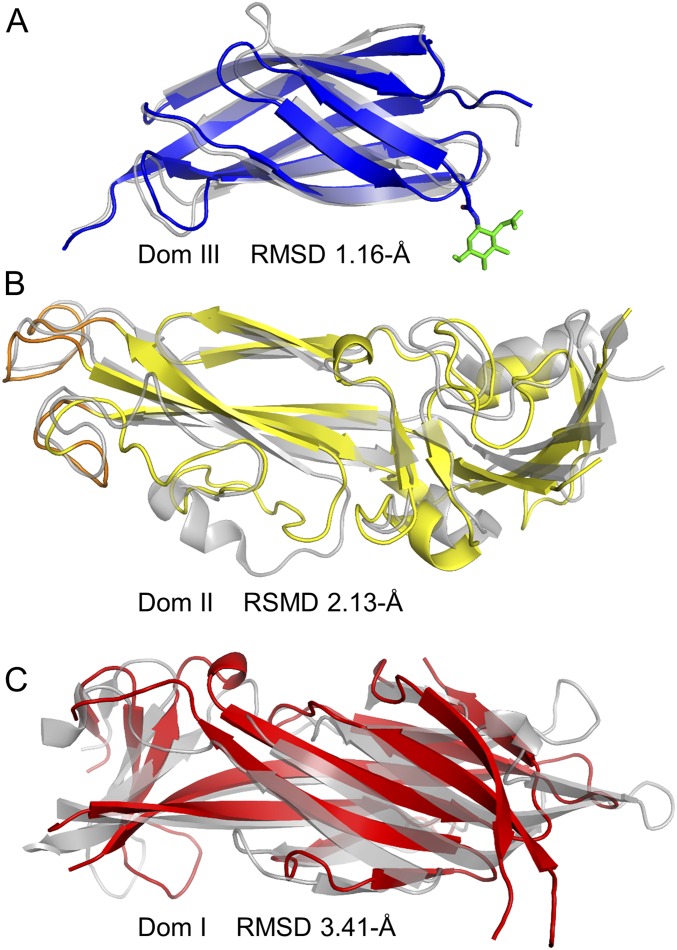

The crystal structure of RVFV Gc in the prefusion conformation constitutes the closest structural relative of SFTSV Gc (∼25% sequence identity) (17). Structural comparison of prefusion RVFV Gc and postfusion SFTSV Gc revealed that the transition from pre- to postfusion states involves major conformational changes to the molecule (Fig. 2). Although the pre- and postfusion conformations of the primarily β-stranded domain III (rmsd of 1.16 Å over 81 Cα residues) are very similar (Fig. S6A), large structural rearrangements are observed upon overlay of domain II (rmsd of 2.13 Å over 117 Cα residues; Fig. S6B) and domain I (3.41 Å rmsd over 109 Cα residues; Fig. S6C) of RVFV Gc and SFTSV Gc. Structural changes to domain I include modifications to secondary structure, where hydrogen bonds linking the first strand, “0,” of the β-sandwich to the third strand, “3,” are displaced and replaced by an extension of the last β-strand, “13” (Fig. 2). A similar restructuring also occurs in the fusogenic rearrangements of SFV E1 protein (24, 31) and DENV E protein (21).

Fig. 2.

Structural rearrangements of phleboviral Gc from prefusion to postfusion conformations. Single protomers of RVFV Gc (PDB ID code 4HJ1) and SFTSV Gc are shown in cartoon representation and colored as in Fig. 1. Glycans are shown as green sticks. Zoom-in panels of domain I are shown on the right side and highlight the strand swap occurring between pre- and postfusion states. In the postfusion conformation, strand 13 (purple) reorientates around the 3–4 loop, forming a β-sheet with strands 3 and 4, and strand 0 (pink) becomes continuous with strand 1 (pink).

Fig. S6.

Overlay analysis of individual SFTSV Gc and RVFV Gc domains. Structures are shown as cartoons, with RVFV Gc colored gray and SFTSV Gc colored according to domain boundaries (domain I, red; domain II, yellow; and domain III, blue). Calculated rmsd values are shown. Overlay of (A) domain III (1.16 Å rmsd over 81 Cα residues), (B) domain II (2.13 Å rmsd of over 117 Cα residues), and (C) domain I (3.41 Å rmsd over 109 Cα residues).

In addition to domain I refolding, we also observed a 24-Å shift in the position of domain III between pre- (RVFV Gc) and postfusion (SFTSV Gc) conformations (Fig. 2). In our postfusion SFTSV Gc structure, the amount of protein−protein contacts made by a single domain III with the rest of the oligomeric assembly is more than two times greater (1,321 Å2) than that observed for domain III in the prefusion RVFV Gc structure (570 Å2) (32). Similarly, an increase in protein–protein contacts made by domain III has been observed in DENV E (21, 33) (from 826 to 1,315 Å2) and SFV E1 (24, 31) proteins (from 572 to 1,530 Å2). It is likely that the formation of such extended protein–protein contacts is energetically favorable and stabilizes the postfusion conformation of the Gc (24).

The Conformationally Conserved Hydrophobic Fusion Loops.

An essential feature of the class-II fusion glycoprotein architecture is the hydrophobic fusion loop located at the apex of domain II, which is inserted into the host membrane and draws the viral and host membranes together upon fusogenic rearrangements of the molecule (21). In contrast to a single fusion loop, which performs this function in alpha- and flaviviruses, structural analysis of RVFV Gc in the prefusion state revealed two putative fusion loops. These loops are also present in SFTSV Gc (Cys650–Cys656, loop 1; Cys691–Cys705, loop 2) and are similarly composed of hydrophobic amino acids, including Ala694, Ala695, Ala701, Trp652, and Phe699 (Fig. 3A). However, in contrast to the prefusion RVFV Gc structure, these loops are fully solvent-accessible and not concealed within oligomeric protein–protein contacts. Interestingly, these loops form a strikingly similar conformation to that observed in RVFV Gc (17), where superposition reveals little difference in structure (rmsd of 0.75 Å over 22 Cα residues) (Fig. 3A). The conserved conformation of the two loops is consistent with that observed in the DENV E protein fusion loop (21) but contrasts the conformational changes observed in the fusion loop of SFV E1 protein (24), which may occur as a result of crystallographic packing.

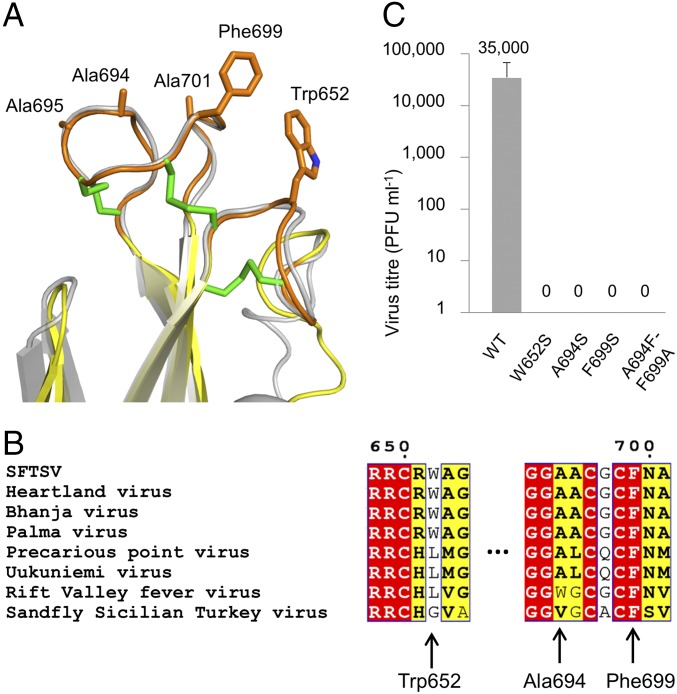

Fig. 3.

The putative fusion loops of SFTSV Gc are conformationally rigid and contain functionally essential residues. (A) An overlay of the fusion loops of SFTSV Gc (colored as in Fig. 1) and RVFV Gc (gray; PDB ID code 4HJ1) reveals highly similar conformations. Side chains from hydrophobic amino acids from SFTSV Gc are shown as orange sticks. Disulphide bonds are shown as green sticks. (B) Sequence alignment of fusion loops across selected phleboviruses. Residues highlighted red are fully conserved and yellow are partially conserved. Residues tested by site-directed mutagenesis are highlighted by arrows. Phe699 is fully conserved, whereas Trp652 is more varied among phleboviral sequences (SI Materials and Methods). (C) SFTSV encoding single and double site-directed mutations at the putative fusion loops were derived by reverse genetics, and the titers of these recombinant viruses, measured in plaque forming units (PFUs), were compared with wild-type (WT) SFTSV.

Aromatic residues Trp652 and Phe699, from loops 1 and 2, respectively, dominate the hydrophobic landscape of these putative fusion loops and extend outwards toward the solvent. Given the relative size and positioning of the Trp652 and Phe699 side chains away from the molecule and toward a hypothetical virion membrane surface, we hypothesized that these residues must be functionally indispensable for virus infectivity. To assess the importance of these residues, we performed rescue of live SFTSV with single mutations W652S, A694S, and F699S and a double mutant, A694F/F699A (Fig. 3C). Although these mutants still passed through the folding pathway required for secretion (Fig. S5), they proved refractory to replication in the context of live virus. These results underscore the sensitivity of this loop region to sequence variation (Fig. 3B), whereby only limited changes in sequence can preserve functionality.

N-Linked Glycosylation on SFTSV Gc.

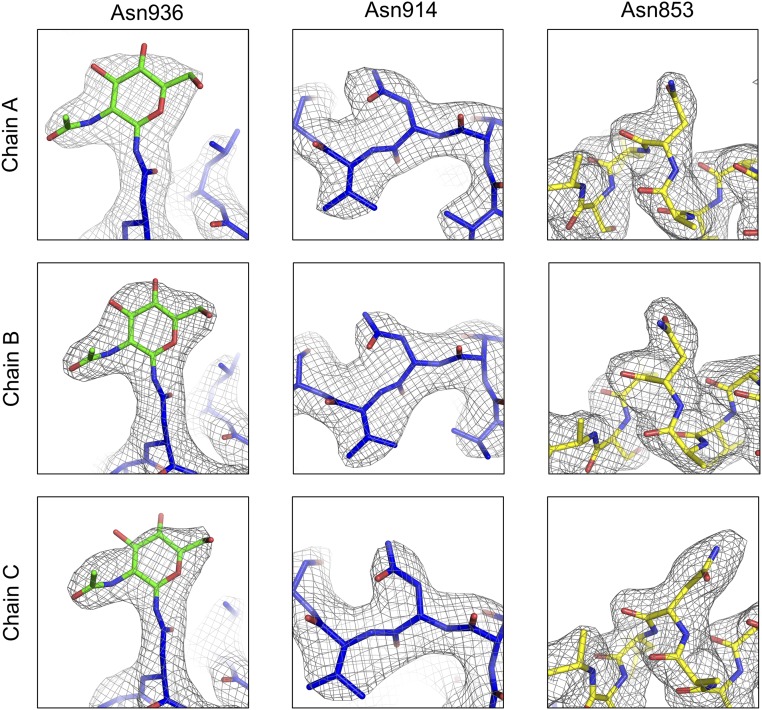

Three N-linked glycosylation sequons are present in our expressed SFTSV Gc ectodomain: As853, Asn914, and Asn936. Analysis of electron density at these sites in each of the three protomers revealed the presence of N-GlcNAc moieties at Asn914 and at least partial occupancy at Asn936. No glycan electron density was observed at Asn853, but as with Asn936, this may arise due to linkage flexibility as well as incomplete sequon occupancy (Fig. S7).

Fig. S7.

Electron density of SFTSV Gc glycans. Three N-linked glycosylation sites are predicted for SFTSV Gc: Asn853, Asn914, and Asn936. The 2Fo-Fc map is shown in gray at 1.0 σ, and only the glycan of Asn936 could be built with confidence.

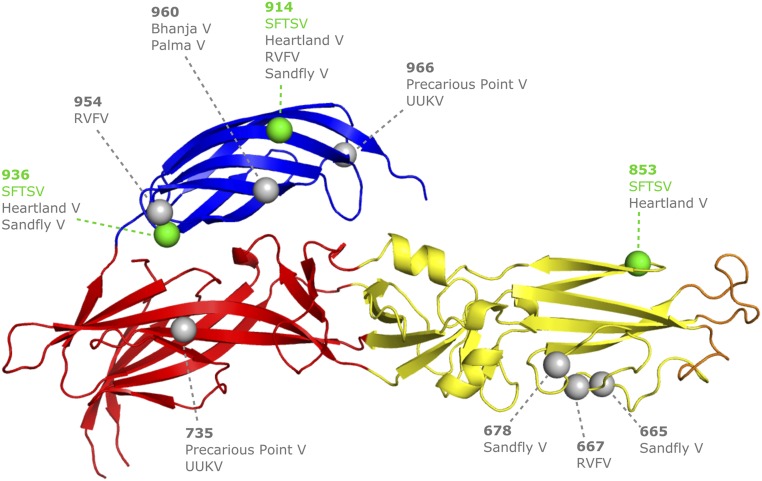

Given that SFTSV entry into a host cell is DC-SIGN–dependent (12) and that the glycans presented by the related UUKV Gc are predominantly oligomannose-type (34–36), it is likely that Gc glycosylation on SFTSV is important for lectin-mediated host cell entry. To assess whether the Gc glycans are accessible to processing during recombinant expression, we performed glycan analysis by HILIC-UPLC (hydrophilic interaction chromatography–ultra performance liquid chromatography) and assessed the levels of oli-gomannose-type glycans using endoglycosidase H digestion (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S8). Unlike our glycoprotein preparations for crystallography, no mannosidase inhibitors were included during expression. We observed negligible levels of hybrid- and oligomannose-type populations with the spectrum dominated with processed complex-type glycans. This suggests a model whereby any oligomannose-type glycans that may contribute to DC-SIGN–mediated attachment are likely to arise only through steric limitations to glycan processing due to the higher order protection effects by the quaternary Gn–Gc assembly. We note that the number and position of glycosylation sites are not well-conserved across phleboviruses, suggesting that the DC-SIGN dependency for infection may be variable (Fig. S9) and that the presentation of putative DC-SIGN glycan ligands is likely to be heterogeneous.

Fig. S8.

Glycan analysis of SFTSV Gc. Enzymatically released glycans of the recombinantly expressed ectodomain of SFTSV Gc, produced in the absence of glycosylation inhibitors, were fluorescently labeled and probed by HILIC-UPLC analysis. (Upper) The overall glycan profile before (black) and after (magenta) endoglycosidase H digestion. Negligible levels of hybrid- and oligomannose-type glycans are revealed, with the spectrum being dominated by processed, complex-type glycans. (Lower) The glycan profile before (black) and after (blue) disialylation, highlighting a significant abundance of sialic acid-containing N-linked glycans.

Fig. S9.

Position of glycosylation sites from selected phleboviruses mapped onto the crystal structure of SFTSV Gc. Predicted glycosylation sites of the eight selected phleboviruses (Fig. S3) were analyzed and placed on equivalent sites on SFTSV Gc as spheres. The site numbering corresponds to the SFTSV Gc amino acid sequence. Glycosylation sites belonging to SFTSV Gc are shown in green, and sites of other viruses are shown in gray.

Histidine-Dependent Function.

Surface exposed histidine residues are a canonical feature of class-II fusion machinery (37, 38). During virion trafficking through endosomal compartments, protonation of histidine–imidazole side chains (at pKa ∼6.0) is thought to trigger conformational changes of the fusion protein, catalyzing the merger of virion and host membranes (14, 15). Such residues are often found in charged environments and may form irreversible salt bridges or hydrogen bonds with negatively charged residues, stabilizing the postfusion conformation of the glycoprotein (38). In alpha- and flaviviruses, many of these functionally important histidines appear to colocalize near the interface between domains I and III (39, 40).

A similar histidine dependency has been observed for phleboviruses, with Gc residues His778, His857, and His1087 having been shown to be key for RVFV infectivity (15). However, in contrast to the localized patch of functionally important histidines in alpha- and flaviviruses, His778, His857, and His1087 are interspersed throughout domains I, II, and III of RVFV Gc, respectively. Although no functional role for His857 was suggested by crystallographic analysis of RVFV Gc, His778 has been proposed to stabilize Gc fusion peptide–host envelope interactions and His1087 colocalizes near the domain I/III interface (17). Interestingly, none of these histidines are conserved with SFTSV Gc. Nevertheless, we were able to identify histidines, His663, His747, and His940, at nearby sites on our SFTSV Gc structure (Fig. 4A). To assess the functional importance of these residues, we introduced single H663M, H747M, and H940M mutations to SFTSV Gc. Although none of these mutations had an observable effect upon protein folding or secretion of soluble SFTSV Gc (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S5), only the H663M mutation could be rescued to levels close to the wild-type using our reverse genetics system. Indeed, H747M was rescued to very low titers, and H940M could not be rescued (Fig. 4B). The sensitivity of the SFTSV lifecycle to these mutations is consistent with the histidine-triggered fusion mechanism observed in alpha- and flaviviruses (39, 41). Additionally, as observed in DENV E, where histidine residues stabilize the postfusion conformation of the glycoprotein (40), H747 forms a hydrogen bond that may stabilize the postfusion conformation of SFTSV Gc (Fig. 4A). The successful rescue of H663M, on the other hand, is suggestive that this residue is not as crucial for virus replication and may not play a substantial role in stabilizing the fusion peptide–host envelope interaction, as suggested for His778 in RVFV (17). These data highlight the importance of surface-exposed histidines in the phleboviral lifecycle and reveal that these residues need not be absolutely conserved among phleboviruses to play similar functional roles.

Fig. 4.

Surface-exposed His663, His747, and His940 on SFTSV Gc domains I and III play integral roles in the virus life cycle. (A) A single SFTSV Gc protomer is shown in cartoon representation (colored as in Fig. 1) with the remainder of the trimer shown as a white van der Waals surface. Selected surface-exposed histidines are shown as purple sticks. Zoom-in panels highlight the location of these residues within each of the three domains, and residues surrounding His747 and His940 from adjacent protomers are shown as white sticks. (B) SFTSV encoding single mutations of His663, His747, and His940 were derived by reverse genetics, and the titers of these recombinant viruses, measured in PFUs, were compared with that of WT SFTSV.

Conclusions

It is now evident that the phleboviral Gc fusion glycoprotein is both functionally and structurally analogous to the fusion glycoproteins of alpha- and flaviviruses. Similarly, our analyses revealed that the phleboviral Gc adopts a trimeric postfusion arrangement, encodes fusion loops at the apex of the molecule, and is functionally dependent upon surface-exposed histidines. In addition to this conserved functionality, alpha-, flavi-, and phleboviruses are also united in their ability to recognize DC-SIGN receptor to enable viral attachment (42, 43), a recognition event facilitated by the presentation of oligomannose-type carbohydrates on the viral surface. These biosynthetically immature glycans are generally an uncommon feature among secreted cellular glycoproteins, and our data suggest that such carbohydrate structures arise from constraints on glycan biosynthesis imposed by the local virus structure during folding and assembly. Indeed, the influence of local protein structure in limiting glycan processing has been observed in many viruses, including alpha- (44) and flaviviruses (45).

It is interesting to contemplate the evolutionary origin of this conserved class-II fold, especially as this architecture has been observed in cell–cell fusion proteins (20). Given the absence of any apparent genetic homology between organisms using this fold for membrane fusion, it is conceivable that the class-II fusion scaffold has evolved considerably from a common viral ancestor, as has been suggested for the lineage of viruses harboring upright β-barrel capsid proteins (46). As revealed by the crystal structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans EFF-1 fusion protein (20), it is also possible that the class-II fold is of cellular origin and viruses have coopted it, adding functionality to the scaffold [e.g., the addition of hydrophobic fusion peptide(s)] in the process. Irrespective, the conservation of this fold is reflective of the absolute necessity for genetically and patho-biologically diverse viruses to preserve a fundamental function throughout a long evolutionary history.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

The ectodomain of SFTSV Gc, residues 563–996 from the M segment (UniProt accession no. R4V2Q5), was cloned into the pHLSec vector (47). HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with 2 mg of DNA per liter of cell media in the presence of 1 μg/mL kifunensine (28). The supernatant was collected 5–6 d after transfection, clarified, and dialyzed against buffer containing 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl. The dialyzed protein was captured by immobilized metal affinity chromatography using a HisTrap nickel column and deglycosylated overnight at room temperature using endoglycosidase F1 (67 μg per 1 mg of protein). Deglycosylated Gc was further purified by SEC chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/30 column in buffer containing 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl. The total yield of purified and deglycosylated SFTSV Gc was ∼0.5 mg/L of tissue culture media.

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

SFTSV Gc ectodomain was crystallized using the sitting-drop vapor method (48) after 5 d with a protein concentration of 3.5 mg/mL in precipitant containing 45% (vol/vol) pentaerythriotol 426 and 0.1 M sodium acetate at pH 4.6 (49). Crystals were cryo-cooled in precipitant solution using liquid nitrogen. Native X-ray data were collected at a 1.008-Å wavelength on a PILATUS 6M detector at Diamond Light Source (DLS) on beamline I03. X-ray data were indexed, integrated, and scaled in XIA2 (50). Crystallographic statistics are summarized in Table 1. For phasing, crystals were soaked in K2PtCl6 for 90 min. Peak anomalous data were collected at the LIII edge of platinum on a PILATUS 6M detector at DLS on beamline I04 at 1.072 Å. Initial phases were obtained using the SAD method in autoSHARP (51), and Buccaneer, as implemented in autoSHARP, was used for initial model building (52). The first rounds of refinement were carried out using Refmac5 (53) and then PHENIX (54) with translation–libration–screw-rotation restraints. Manual model building was performed in Coot (55), and final structure validation was done using MolProbity (56).

Generation of Recombinant SFTSV from cDNA.

Plasmid pTVT7-HB29M containing a full-length cDNA to the HB29 M segment (GenBank accession no. KP202164) was mutated by site-directed mutagenesis to introduce the following single amino acid substitutions (W652S, A694S, F699A, C563M, C604M, C617M, H663M, H747M, and H940M) and double amino acid substitution (A694F-F699A) into the HB29 M polyprotein. Recombinant SFTSV was generated as previously described (57). Three independent attempts were performed for each Gc mutant with corresponding wild-type controls. After 5 d, the virus-containing supernatants were collected, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, and stored at –80 °C. Stocks of recombinant viruses were grown in Vero E6 cells at 37 °C by infecting at multiplicity of infection of 0.01 and harvesting the culture medium at 7 d postinfection.

Virus Titration by Plaque Assay.

Vero E6 cells were infected with serial dilutions of virus and incubated under an overlay consisting of DMEM supplemented with 2% FCS and 0.6% Avicel (FMC BioPolymer) at 37 °C for 7 d. Cell monolayers were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Following fixation, cell monolayers were stained with Giemsa to visualize plaques.

SI Materials and Methods

Western Blot Analysis.

The hexa-histidine tag was probed using a primary mouse antibody specific to the poly-histidine tail (Qiagen product no. 34660) and a horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma product no. A1068). Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) was used for detection according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Buffer Exchange by Dialysis for SEC Analysis.

For oligomerization studies, SFTSV Gc purified by SEC in 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, was placed in a Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette (Thermo Scientific) and dialyzed against 3,000× volume of buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Citrate-NaOH, pH 5.0. Dialysis was performed in two stages: first at room temperature for 3 h and second at 4 °C overnight in fresh buffer.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

A series of site-directed mutants (C563M, C604M, C617M, H663M, H747M, H940M, W562S, A694S, F699S, and the A694F/F699A double mutant) specific to the SFTSV Gc ectodomain were prepared by PCR-driven overlap extension, as previously described (58). Each SFTSV Gc ectodomain mutant was cloned into the pHLSec vector (47), which adds a hexa-histidine tail to the C terminus of the construct. All SFTSV Gc mutants were of the same length as the crystallized soluble ectodomain, residues 563–996. Site-directed SFTSV Gc mutant constructs were expressed in HEK293T cells in a 24-well plate format using Lipofectamine 2000 as the transfection reagent. HEK293T supernatant was probed for soluble SFTSV Gc expression by Western blot 48 h following transfection.

Multiple Sequence Alignment.

A list of representative phlebovirus sequences was based on previously published work (59). The sequences were obtained from GenBank (accession numbers are given in parentheses): Bhanja virus strain M3811 (JQ956377), Heartland virus (JX005845), Palma virus strain M3443 (JQ956380), Precarious Point virus (HM566179), RVFV strain Smithburn (DQ380193.1), Sandfly fever Turkey virus (NC_015411), SFTSV strain HN6 (HQ141596), and UUKV (UUKGPM). The sequences were aligned using the online Clustal Omega (60) server available at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The sequence alignment was rendered using the online server ESPript 3.0 (61) (espript.ibcp.fr).

Glycan Analysis.

Glycan release, labeling, and analysis were performed as described previously (62, 63). Briefly, a 10-μg sample of purified recombinant SFTSV Gc protein was subjected to SDS/PAGE analysis using Coomassie blue stain to identify the target glycoprotein. The SFTSV Gc gel band was excised and washed with five cycles of alternating acetonitrile and water washes. Glycan release and labeling was performed as described previously. Briefly, N-linked glycans were released enzymatically by incubation of the washed gel pieces with peptide N-Glycosidase F [New England Biolabs (NEB)] at 37 °C for 16 h. Glycans were eluted by extensive washing with water followed by drying in a SpeedVac concentrator. The isolated glycans were fluorescently labeled by resuspension in 30 μL of water followed by addition of 80 μL labeling mixture [30 mg/mL 2-aminobenzoic acid and 45 mg/mL sodium cyanoborohydride in a solution of sodium acetate trihydrate (4% wt/vol) and boric acid (2% wt/vol) in methanol] and incubated at 80 °C for 1 h. Excess label was removed using Spe-ed Amide-2 cartridges.

The abundance of sialic acids and the oligomannose content was determined by digestion with α-neuraminidase (NEB) and endoglycosidase H (NEB), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Digested glycans were extracted using a polyvinylidene fluoride protein-binding membrane plate (Millipore) and then resolved by HILIC-UPLC using a 2.1-mm × 10-mm Acquity BEH Amide Column (1.7-μm particle size) (Waters) as described previously (63). Data processing was performed using Empower 3 software.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of beamlines I03 and I04 at DLS for support. K.H. is supported by Medical Research Council (MRC) Grant MR/N00065X/1, and J.T.H. by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (649053). Work in the M.C. laboratory is supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative Neutralizing Antibody Center CAVD grant and the Scripps CHAVI-ID (1UM1AI100663). Work at the University of Glasgow is supported by Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award 099220/Z/12/Z (to R.M.E.). T.A.B. is supported by the MRC (MR/L009528/1 and MR/N002091/1). The Wellcome Trust Centre of Human Genetics is funded through a Core Award (090532/Z/09/Z).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5G47).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1603827113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yu X-J, et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1523–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui N, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome bunyavirus-related human encephalitis. J Infect. 2015;70(1):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding F, et al. Epidemiologic features of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China, 2011-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(11):1682–1683. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam TT-Y, et al. Evolutionary and molecular analysis of the emergent severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Epidemics. 2013;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, et al. Antibodies against severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in healthy persons, China, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(8):1355–1357. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.131796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulmanen I, Seppälä P, Pettersson RF. In vitro translation of Uukuniemi virus-specific RNAs: Identification of a nonstructural protein and a precursor to the membrane glycoproteins. J Virol. 1981;37(1):72–79. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.1.72-79.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freiberg AN, Sherman MB, Morais MC, Holbrook MR, Watowich SJ. Three-dimensional organization of Rift Valley fever virus revealed by cryoelectron tomography. J Virol. 2008;82(21):10341–10348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01191-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huiskonen JT, Overby AK, Weber F, Grünewald K. Electron cryo-microscopy and single-particle averaging of Rift Valley fever virus: Evidence for GN-GC glycoprotein heterodimers. J Virol. 2009;83(8):3762–3769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02483-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overby AK, Pettersson RF, Grünewald K, Huiskonen JT. Insights into bunyavirus architecture from electron cryotomography of Uukuniemi virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2375–2379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708738105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman MB, Freiberg AN, Holbrook MR, Watowich SJ. Single-particle cryo-electron microscopy of Rift Valley fever virus. Virology. 2009;387(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lozach PY, et al. DC-SIGN as a receptor for phleboviruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(1):75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann H, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia virus glycoproteins are targeted by neutralizing antibodies and can use DC-SIGN as a receptor for pH-dependent entry into human and animal cell lines. J Virol. 2013;87(8):4384–4394. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02628-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmon B, et al. Rift Valley fever virus strain MP-12 enters mammalian host cells via caveola-mediated endocytosis. J Virol. 2012;86(23):12954–12970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02242-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozach PY, et al. Entry of bunyaviruses into mammalian cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(6):488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Boer SM, et al. Acid-activated structural reorganization of the Rift Valley fever virus Gc fusion protein. J Virol. 2012;86(24):13642–13652. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01973-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvas JA, Popov VL, Paulucci-Holthauzen A, Aguilar PV. Extracellular vesicles mediate receptor-independent transmission of novel tick-borne bunyavirus. J Virol. 2015;90(2):873–886. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02490-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dessau M, Modis Y. Crystal structure of glycoprotein C from Rift Valley fever virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(5):1696–1701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217780110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rey FA, Heinz FX, Mandl C, Kunz C, Harrison SC. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 A resolution. Nature. 1995;375(6529):291–298. doi: 10.1038/375291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lescar J, et al. The Fusion glycoprotein shell of Semliki Forest virus: An icosahedral assembly primed for fusogenic activation at endosomal pH. Cell. 2001;105(1):137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Vargas J, et al. Structural basis of eukaryotic cell-cell fusion. Cell. 2014;157(2):407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature. 2004;427(6972):313–319. doi: 10.1038/nature02165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiasny K, Allison SL, Marchler-Bauer A, Kunz C, Heinz FX. Structural requirements for low-pH-induced rearrangements in the envelope glycoprotein of tick-borne encephalitis virus. J Virol. 1996;70(11):8142–8147. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8142-8147.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bitto D, Halldorsson S, Caputo A, Huiskonen JT. Low pH and anionic lipid dependent fusion of uukuniemi phlebovirus to liposomes. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(12):6412–6422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.691113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbons DL, et al. Conformational change and protein-protein interactions of the fusion protein of Semliki Forest virus. Nature. 2004;427(6972):320–325. doi: 10.1038/nature02239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao LH, Klein DE, Schmidt AG, Peña JM, Harrison SC. Sequential conformational rearrangements in flavivirus membrane fusion. eLife. 2014;3:e04389. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Espósito DL, Nguyen JB, DeWitt DC, Rhoades E, Modis Y. Physico-chemical requirements and kinetics of membrane fusion of flavivirus-like particles. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1702–1711. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbein AD, Tropea JE, Mitchell M, Kaushal GP. Kifunensine, a potent inhibitor of the glycoprotein processing mannosidase I. JBC. 1990;265(26):15599–15605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang VT, et al. Glycoprotein structural genomics: Solving the glycosylation problem. Structure. 2007;15(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaney MC, Rey FA. Class II enveloped viruses. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13(10):1451–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee B, et al. Molecular recognition of human ephrinB2 cell surface receptor by an emergent African henipavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(17):E2156–E2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501690112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roussel A, et al. Structure and interactions at the viral surface of the envelope protein E1 of Semliki Forest virus. Structure. 2006;14(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):6986–6991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832193100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crispin M, et al. Uukuniemi Phlebovirus assembly and secretion leave a functional imprint on the virion glycome. J Virol. 2014;88(17):10244–10251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01662-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuismanen E. Posttranslational processing of Uukuniemi virus glycoproteins G1 and G2. J Virol. 1984;51(3):806–812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.806-812.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pesonen M, Kuismanen E, Pettersson RF. Monosaccharide sequence of protein-bound glycans of Uukuniemi virus. J Virol. 1982;41(2):390–400. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.2.390-400.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mueller DS, et al. Histidine protonation and the activation of viral fusion proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 1):43–45. doi: 10.1042/BST0360043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kampmann T, Mueller DS, Mark AE, Young PR, Kobe B. The role of histidine residues in low-pH-mediated viral membrane fusion. Structure. 2006;14(10):1481–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin ZL, Zheng Y, Kielian M. Role of conserved histidine residues in the low-pH dependence of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein. J Virol. 2009;83(9):4670–4677. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02646-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nayak V, et al. Crystal structure of dengue virus type 1 envelope protein in the postfusion conformation and its implications for membrane fusion. J Virol. 2009;83(9):4338–4344. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02574-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritz R, Stiasny K, Heinz FX. Identification of specific histidines as pH sensors in flavivirus membrane fusion. J Cell Biol. 2008;183(2):353–361. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klimstra WB, Nangle EM, Smith MS, Yurochko AD, Ryman KD. DC-SIGN and L-SIGN can act as attachment receptors for alphaviruses and distinguish between mosquito cell- and mammalian cell-derived viruses. J Virol. 2003;77(22):12022–12032. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12022-12032.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tassaneetrithep B, et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197(7):823–829. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crispin M, et al. Structural plasticity of the Semliki Forest virus glycome upon interspecies transmission. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(3):1702–1712. doi: 10.1021/pr401162k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hacker K, White L, de Silva AM. N-linked glycans on dengue viruses grown in mammalian and insect cells. J Gen Virol. 2009;90(Pt 9):2097–2106. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.012120-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abrescia NG, Bamford DH, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. Structure unifies the viral universe. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:795–822. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060910-095130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aricescu AR, Lu W, Jones EY. A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 10):1243–1250. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter TS, et al. A procedure for setting up high-throughput nanolitre crystallization experiments. Crystallization workflow for initial screening, automated storage, imaging and optimization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61(Pt 6):651–657. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gulick AM, Horswill AR, Thoden JB, Escalante-Semerena JC, Rayment I. Pentaerythritol propoxylate: A new crystallization agent and cryoprotectant induces crystal growth of 2-methylcitrate dehydratase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58(Pt 2):306–309. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901018832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winter G. xia2: An expert system for macromolecular crystallography data reduction. J Appl Cryst. 2010;43(1):186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vonrhein C, Blanc E, Roversi P, Bricogne G. Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;364:215–230. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-266-1:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 9):1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vagin AA, et al. REFMAC5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brennan B, et al. Reverse genetics system for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. J Virol. 2015;89(6):3026–3037. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03432-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(4):924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swei A, et al. The genome sequence of Lone Star virus, a highly divergent bunyavirus found in the Amblyomma americanum tick. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sievers F, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robert X, Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Web Server issue):W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neville DC, Dwek RA, Butters TD. Development of a single column method for the separation of lipid- and protein-derived oligosaccharides. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(2):681–687. doi: 10.1021/pr800704t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pritchard LK, et al. Structural constraints determine the glycosylation of HIV-1 envelope trimers. Cell Reports. 2015;11(10):1604–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]