Significance

Locomotion requires peripheral sensory feedback from mechanosensitive proprioceptors. The molecular mechanisms underlying this proprioceptive locomotion control are largely unknown. Here we report that tmc, the Drosophila ortholog of the mammalian deafness gene tmc1, is expressed in larval peripheral sensory neurons and that these neurons require transmembrane channel-like (TMC) to respond to bending of the larval body. We further report that loss of TMC function causes locomotion defects. Finally, mammalian TMC1/2 are shown to rescue locomotion defects in tmc mutant larvae, providing evidence for a functional conservation between Drosophila and mammalian TMC proteins.

Keywords: proprioception, locomotion, mechanosensation

Abstract

Drosophila larval locomotion, which entails rhythmic body contractions, is controlled by sensory feedback from proprioceptors. The molecular mechanisms mediating this feedback are little understood. By using genetic knock-in and immunostaining, we found that the Drosophila melanogaster transmembrane channel-like (tmc) gene is expressed in the larval class I and class II dendritic arborization (da) neurons and bipolar dendrite (bd) neurons, both of which are known to provide sensory feedback for larval locomotion. Larvae with knockdown or loss of tmc function displayed reduced crawling speeds, increased head cast frequencies, and enhanced backward locomotion. Expressing Drosophila TMC or mammalian TMC1 and/or TMC2 in the tmc-positive neurons rescued these mutant phenotypes. Bending of the larval body activated the tmc-positive neurons, and in tmc mutants this bending response was impaired. This implicates TMC’s roles in Drosophila proprioception and the sensory control of larval locomotion. It also provides evidence for a functional conservation between Drosophila and mammalian TMCs.

Proprioception—the sense of positions, orientations, and movements of body parts—provides sensory feedback information for animals to maintain the right gestures and coordinate their body movements (1, 2). It has been known for centuries that proprioception is mediated by mechanosensitive proprioceptors (1, 3) such as mammalian muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs (2, 3). In insects, mechanosensory campaniform sensilla, trichoform sensilla, chordotonal organs, and stretch receptors reportedly serve proprioceptive roles (4–10).

Proprioceptors integrate various mechanical cues, which are thought to be detected by mechanogated ion channels (11), to keep track of the relative positions and to coordinate the movements of different parts of the body (11). The molecular mechanisms underlying proprioceptive transduction have just begun to be elucidated. Among mechanosensitive ion channel candidates such as certain members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (12–14), degenerin/epithelial sodium channels (DEG/ENaC) (15–17), Piezo (18–20), transmembrane channel-like (TMC) (21), K2P (22–24), and MscL (large-conductance mechanosensitive channel) (24, 25), TRPN and DEG/ENaC ion channels have been proposed to be mechanosensitive ion channels involved in proprioception in nematodes (26, 27), fruit flies (6, 9, 10) and zebrafish (28). Recently, it was reported that Piezo2 is essential for the mechanosensitivity of mammalian proprioceptors (29). However, whether other putative mechanosensitive ion channels participate in proprioception has remained unclear.

Tmc1, the founding member of the TMC gene family, was first reported for its role in auditory sensation owing to its genetic linkage to human deafness (30, 31) and its requirement for hearing in rodents (31). Eight transmembrane channel-like (tmc) genes have been identified in human and mouse genomes (32, 33). It has been suggested that TMC1 and TMC2 are likely essential components of the transduction channel complex in hair cells of the mouse inner ear (21, 34). The tmc-1 gene in nematode was reported to encode a sodium-sensitive cation channel and participates in sensing high concentrations of sodium (35), suggestive of diverse functions of the tmc genes. There is only one tmc gene (CG46121) in the Drosophila genome (32, 33), providing an opportunity to study potentially diverse roles of the tmc gene.

Here we report a previously unidentified role of the Drosophila tmc gene. We found that Drosophila TMC is expressed and functions in larval class I and class II dendritic arborization (da) neurons and bipolar dendrite (bd) neurons and likely provides sensory feedback for larval locomotion (7, 9). Larvae with loss-of-function mutation of tmc exhibited defective locomotion, and this phenotype can be rescued by expressing Drosophila TMC or mouse TMC1 and/or TMC2 in tmc-positive neurons. Our study shows that Drosophila TMC contributes to mechanosensation in the body-wall sensory neurons and plays a role in locomotion of Drosophila larvae.

Results

Generation of Drosophila tmc Mutants.

The tmc genes encode proteins with putative transmembrane domains that potentially function as channels (32, 33). Drosophila has one tmc gene (CG46121), which is evolutionarily related to mammalian tmc1 and tmc2 genes (32, 33). The Drosophila TMC protein sequence is highly conserved with TMC family members in other species, particularly in the predicted transmembrane domains that contain the characteristic TMC motif (Fig. S1), although it has a much longer loop flanked by two putative transmembrane domains (Fig. S1).

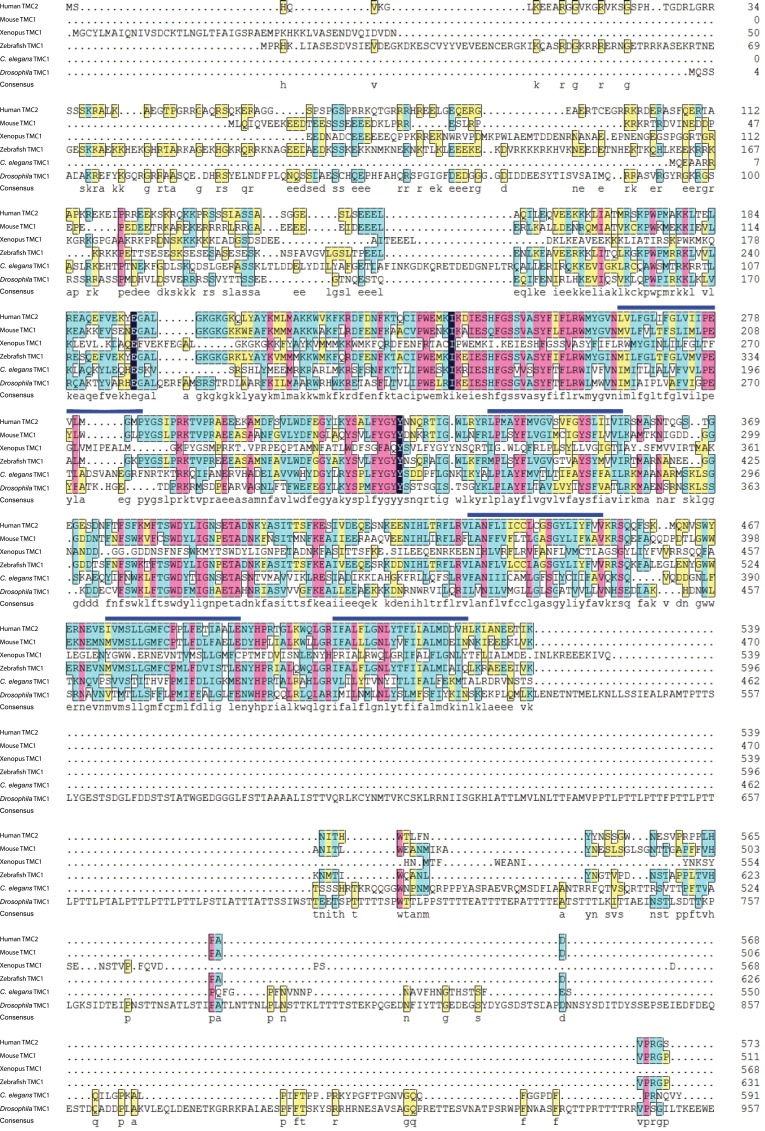

Fig. S1.

Protein sequence alignment between representative members of the TMC family, including human TMC2 (NP_542789), mouse TMC1 (NP_083229), Xenopus TMC1 (predicted, XP_002935639.1), zebrafish TMC1 (AIK19895.1), C. elegans TMC1 (NP_508221), and Drosophila TMC (AFH04369). Blue bars above the sequences indicate predicted transmembrane segments. Green shading indicates the predicted TMC domains. Transmembrane and TMC domains are largely conserved. Drosophila TMC is much longer than that in other TMC family members.

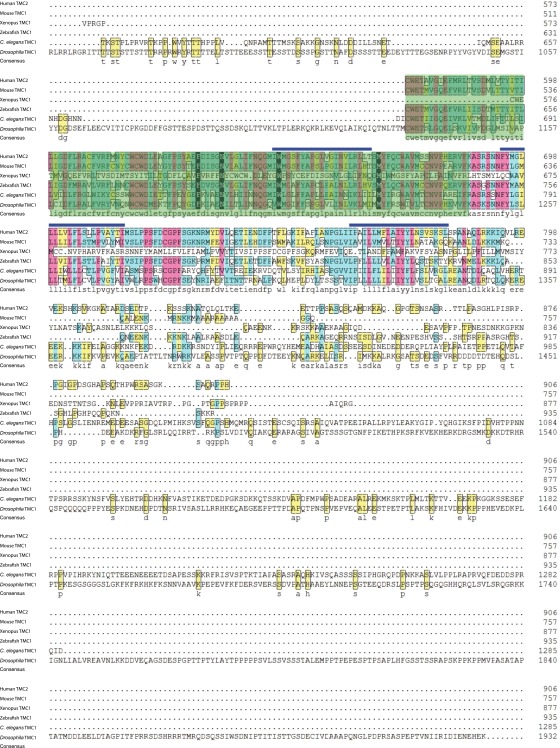

To investigate the Drosophila tmc gene function, we first generated a transgenic reporter allele, tmc-Gal4, and one tmc knock-in reporter allele, tmcGal4, in which the bulk of the coding sequence is removed (Fig. 1A). For tmcGal4, the Gal4 gene and the miniwhite gene were inserted into the tmc locus near the translation initiation codon of the Drosophila TMC isoform PD via ends-out homologous recombination (36, 37) so that about 7,000 bp of the tmc gene were replaced by the reporter construct (Fig. 1A). As a result, more than 1,000 amino acids, about one-half of the coding sequence of tmc, were deleted in the tmcGal4 allele, likely resulting in a null mutation of the tmc gene. This was confirmed by RT-PCR, which detected no tmc RNA in tmcGal4 larvae (Fig. 1B). tmc RNA was restored when we expressed a UAS-tmc rescue construct in tmcGal4 mutants via the Gal4 (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Generation of tmc reporter and mutant alleles. (A) Targeting schemes for the generation of the tmcGal4 mutant allele by homologous recombination and the generation of the tmc-Gal4 transgene. Black bars under CG46121-PD indicate the predicted transmembrane segments of Drosophila TMC (33). Red Bars above CG46121-PD indicate the predicted TMC domain (32). (B) Confirmation of the tmcGal4 mutation as a null allele for transcript expression by RT-PCR.

Drosophila TMC Is Expressed in Class I da Neurons, Class II da Neurons, and bd Neurons.

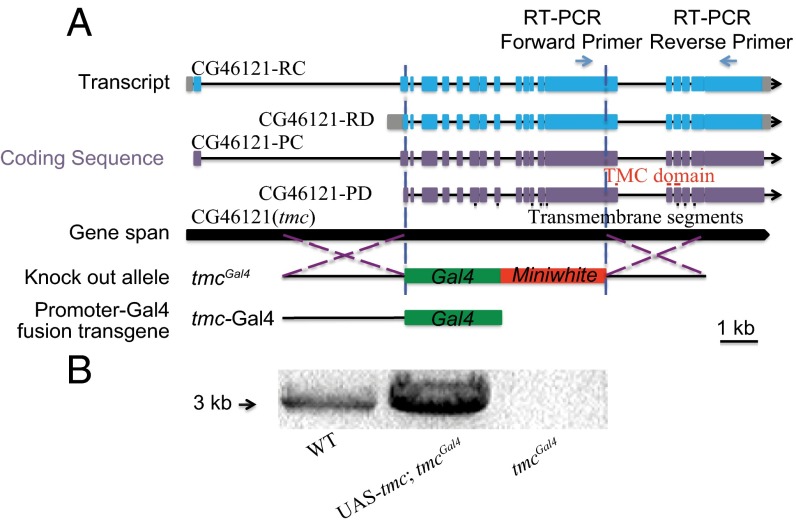

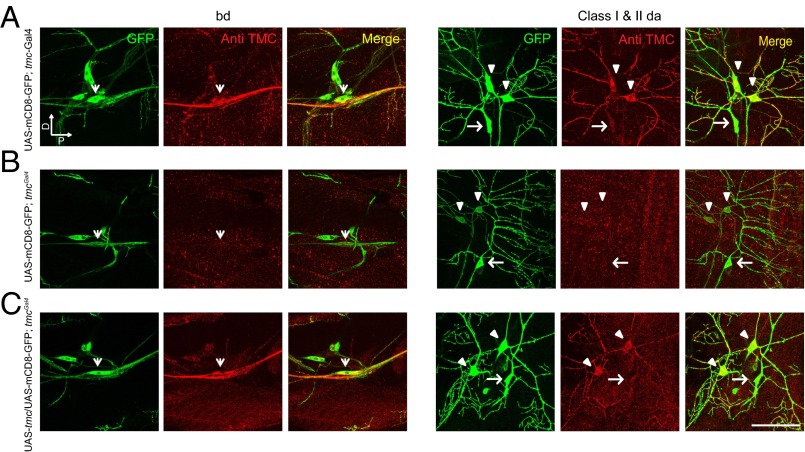

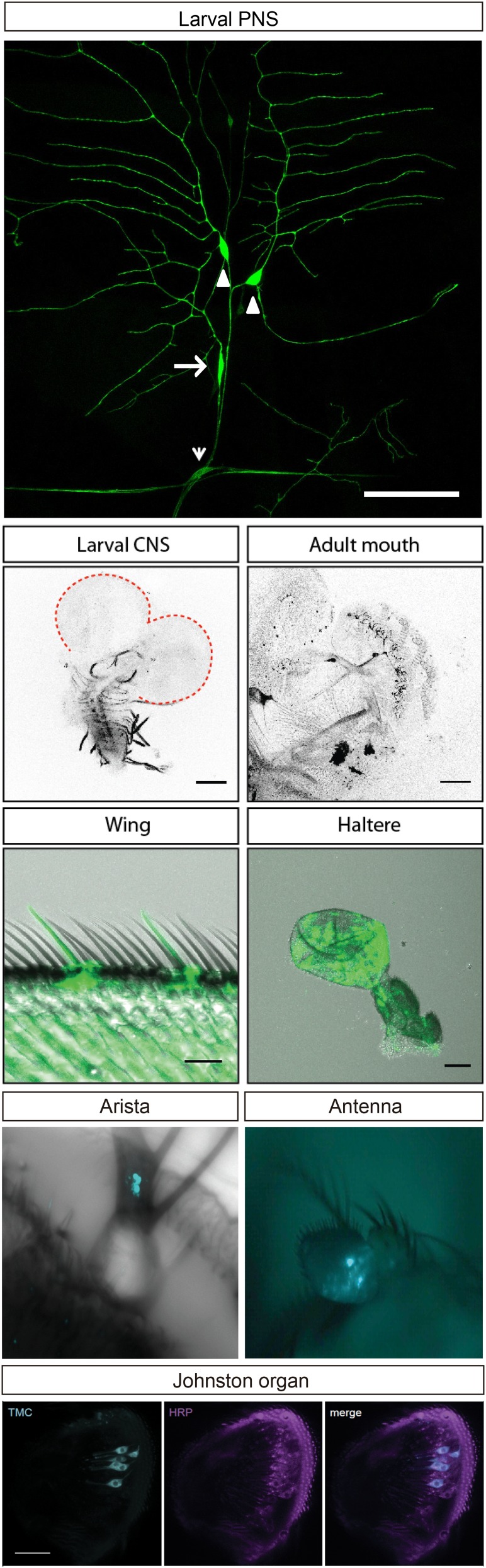

To gain first insights into the roles of Drosophila TMC, we first tested whether tmc is expressed in sensory neurons in Drosophila larvae by using the Gal4/UAS system. The tmc-Gal4 and tmcGal4 lines were used to drive the expression of the reporter UAS-mCD8-GFP. As revealed by the morphology and the position of the mCD8-GFP–positive neurons, class I and class II da neurons as well as bd neurons are labeled with both tmc-Gal4 and tmcGal4 (Fig. 2 A and B). We have also generated another independent tmc-Gal4 line and observed expression in the same cells (Fig. S2). In adult flies, tmc-Gal4 labeled subsets of neurons in the mouth parts, olfactory neurons in the antenna (38), wing bristle neurons (39), haltere neurons (40), arista neurons (41), and many other sensory neurons (Fig. S2), including a subset of chordotonal (Cho) neurons (42), the hearing neurons of the fly (Fig. S2). This broad expression pattern of tmc raises the possibility that the single Drosophila tmc gene might have multiple functions in different sensory organs, which might be split among the eight mammalian members of the TMC family.

Fig. 2.

Expression pattern of tmc. (A) Labeling via tmc-Gal4 and endogenous expression of Drosophila TMC in class I and class II da neurons and bd neurons. (B) Labeling via tmcGal4 revealing the loss of expression of Drosophila TMC in class I and class II da neurons and bd neurons. (C) Restoration of Drosophila TMC expression in class I and class II da neurons and bd neurons by expressing Drosophila TMC. Arrowheads: bd neuron. Triangle: class I da neuron. Arrows: class II da neuron. Green indicates GFP signals, and red indicates TMC immunofluorescent signals. (A, Left) “D” indicates dorsal, and “P” indicates posterior. (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

Fig. S2.

tmc-Gal4 expression in larvae and adult. tmc-Gal4 labels class I and class II da neurons and bd neurons. Arrowhead: bd neuron. Triangle: class I da neuron. Arrow: class II da neurons. There was no detectable expression of tmc-Gal4 in the larval CNS. In the adult fly, tmc-Gal4 labels sensory neurons in the mouth, wing, haltere, arista, the third segment of the antenna, and the Johnston organ.

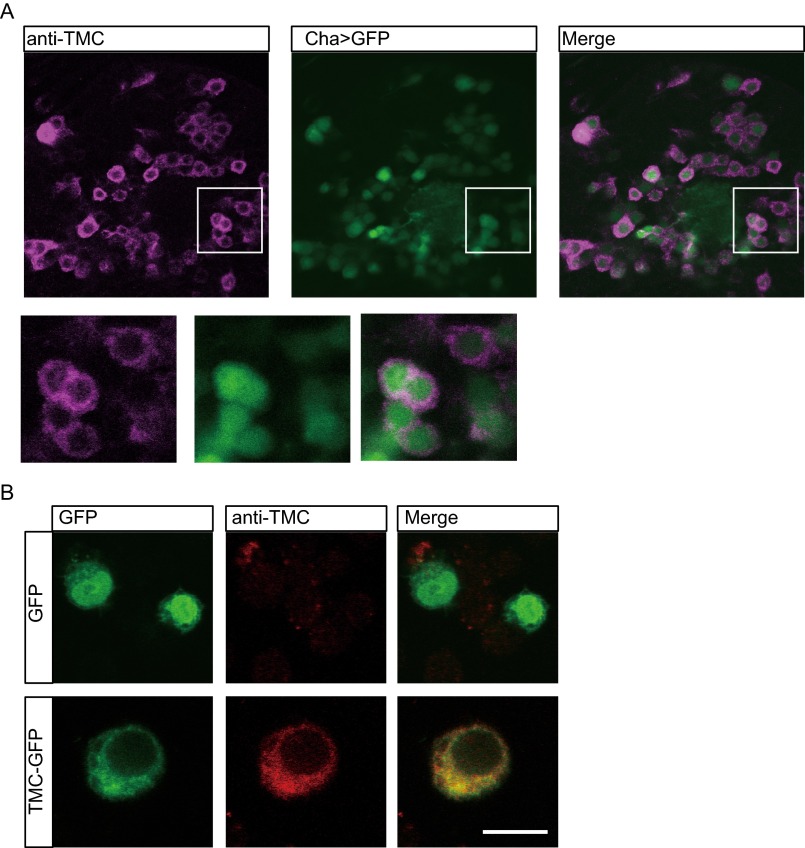

To examine the intrinsic expression pattern of Drosophila TMC, we generated an antibody against the C terminus of the Drosophila TMC protein. We first demonstrated the specificity of the antibody by immunostaining Drosophila TMC ectopically expressed in the fly brain neurons via Cha-Gal4 or in cultured Drosophila S2 cell lines. We found that immunofluorescence could be detected only in Drosophila TMC-expressing cells, suggesting that the antibody is specific (Fig. S3). Immunostaining of the larval body wall identified Drosophila TMC in class I and II da neurons and bd neurons in wild-type larvae (Fig. 2A), although no obvious immunofluorescence could be observed in tmc mutant larvae (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the immunofluorescence was restored by expressing of Drosophila TMC in tmc mutants (Fig. 2C). All of these results suggest that the antibody specifically recognizes Drosophila TMC proteins that are expressed in class I and class II da neurons and bd neurons.

Fig. S3.

Validation of the TMC antibody. (A) Immunostaining of Drosophila TMC ectopically expressed in the fly brain. Drosophila TMC was expressed in excitatory cholinergic neurons via Cha-Gal4. Fly genotype: Cha-Gal4, UAS-GFP; UAS-tmc. (Inset) Zoom-in of the cell-body region documenting enrichment of TMC around the cell membrane. (B) Immunostaining of TMC ectopically expressed in Drosophila S2R+ cells. Cells were transfected with TMC (Lower) or without TMC (Upper).

TMC Regulates Larval Locomotion.

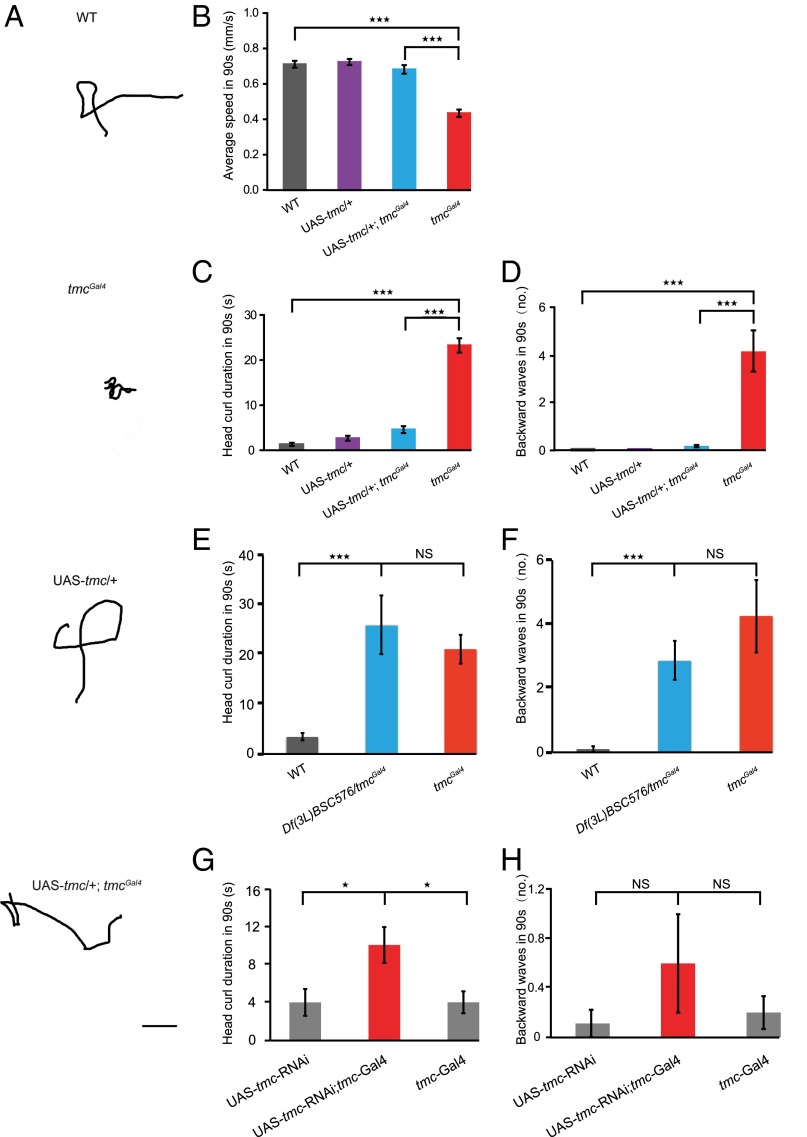

Given that class I da neurons and bd neurons that express tmc (Fig. 2A) are proprioceptors that provide feedback on larval crawling (7, 9), we examined the locomotion behavior of tmc mutant larvae. The locomotion trajectories of tmcGal4 larvae were distinct from those of wild-type w1118 larvae (Fig. 3A). We found that the crawling speeds of tmcGal4 larvae were significantly reduced compared with control larvae (Fig. 3B). Given that Drosophila larval locomotion includes several different types of movements, including linear forward crawling, turns, backward locomotion, and other movements (43, 44), we then analyzed the locomotion behavior in details. We found that tmcGal4 larvae exhibited a significantly enhanced head curl behavior, with the head curling to the left, right, or up, whereas the abdomen remained still (Fig. 3C and Movies S1 and S2); the larvae also showed increased backward locomotion (Fig. 3D and Movies S1 and S2). Both these phenotypes characterize abnormal locomotion behaviors that ensue from the loss of proprioceptive feedback (7). To confirm that these behavioral defects are indeed caused by tmc mutation, we first crossed tmcGal4 mutants with deficient flies that harbor a genomic deletion covering the tmc gene. We found that the behavioral defects of tmc mutants could not be complemented by the deletion allele (Fig. 3 E and F). Moreover, we found that knocking down the tmc gene by crossing tmc-Gal4 flies with UAS-tmc-RNAi flies led to similar although less severe behavioral defects, including enhanced head curl behavior and a tendency for backward movements (Fig. 3 G and H). Furthermore, we found that the behavioral defects in the tmcGal4 larvae were fully rescued by expressing Drosophila TMC using the Gal4 driver in tmcGal4 (Fig. 3 A–D). Taken together, our results demonstrate that Drosophila TMC is required for the normal crawling behavior in Drosophila larvae, likely functioning in class I and class II da neurons and bd neurons.

Fig. 3.

tmc is important for Drosophila larval locomotion. (A) Crawling trajectories of wild-type w1118 larvae, tmcGal4 mutants, UAS-tmc controls, and UAS-tmc; tmcGal4 larvae. (Scale bar, 1 cm.) Restoring tmc expression rescued the locomotion defects in locomotion speed (B), head curl duration in 90 s (C), and backward wave numbers (D) in 90 s. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to test for the statistical significance of the differences between wild-type w1118, tmcGal4, UAS-tmc, and rescue (UAS-tmc; tmcGal4) larvae. ***P < 0.001. (E) Head curl duration (in 90 s) and (F) backward wave numbers (in 90 s) are comparable between tmcGal4 and Df(3L)BSC576/tmcGal4 larvae, with significant increase compared with wild-type control. One-way ANOVA was used to test for the statistical significance of the differences between tmcGal4, UAS-tmc, and rescue (UAS-tmc; tmcGal4) larvae, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. ***P < 0.001. NS, not significant. (G) Head curl duration in 90 s and (H) backward wave numbers in 90 s of tmc-Gal4, UAS-tmc-RNAi, and tmc knockdown (UAS-tmc-RNAi; tmc-Gal4) larvae. One-way ANOVA was used to test for the statistical significance of the differences between tmc-Gal4, UAS-tmc-RNAi, and tmc knockdown (UAS-tmc-RNAi; tmc-Gal4) larvae, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. *P < 0.05. NS, not significant. n > 10.

Drosophila TMC-Positive Neurons Show Drosophila TMC-Dependent Response to Body Bending.

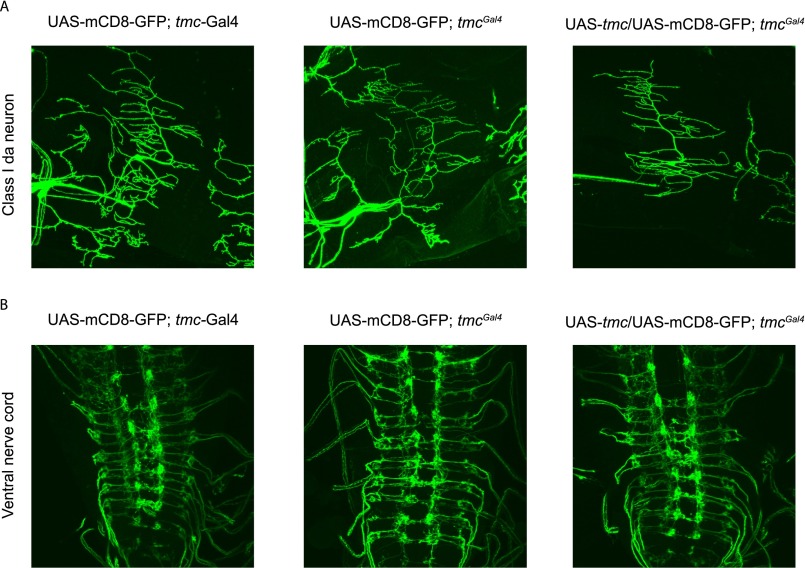

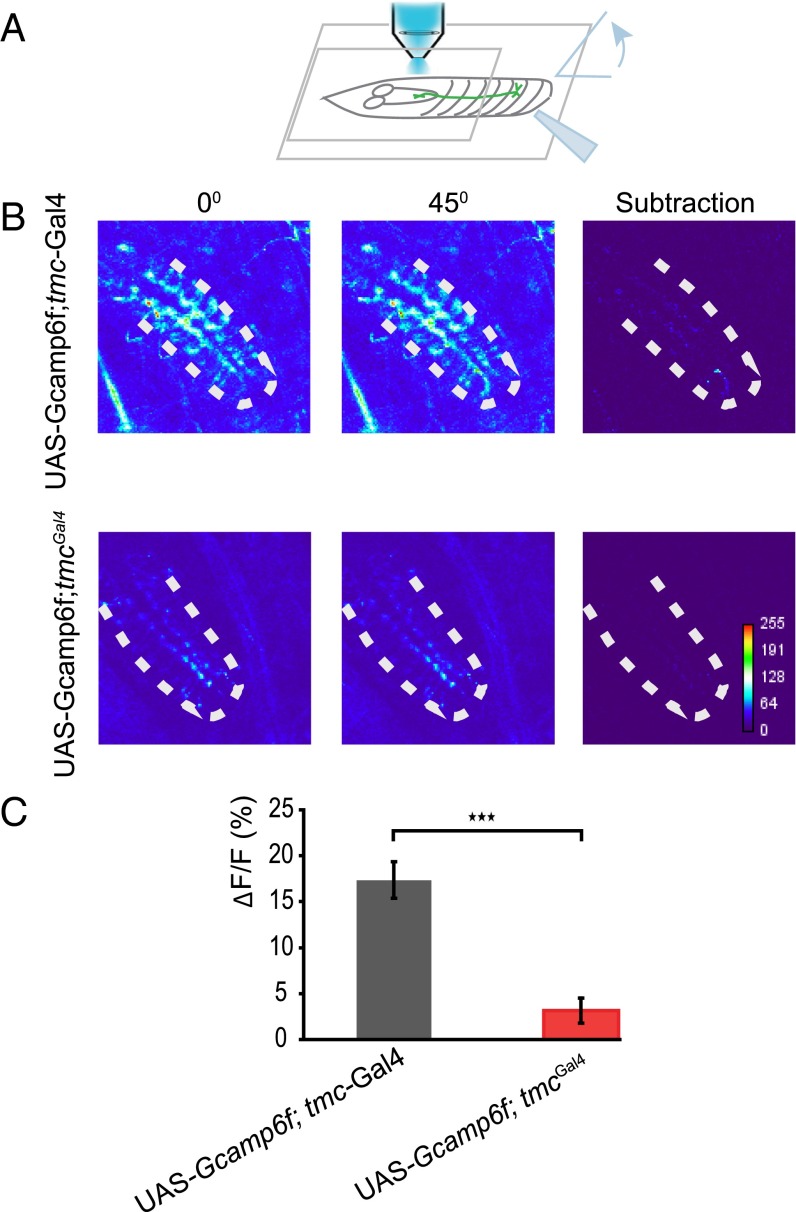

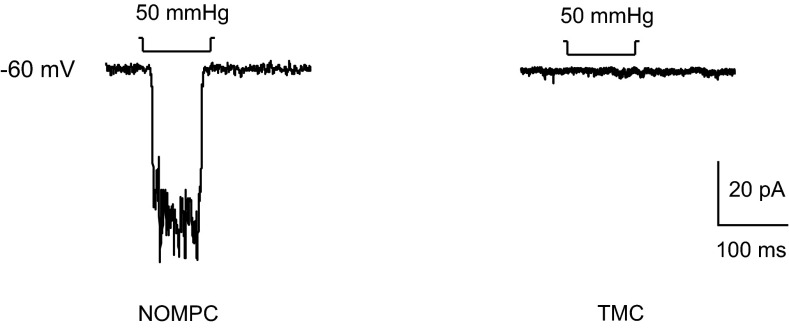

Mutation of Drosophila tmc did not cause obvious defects in the dendrite morphology of class I da neurons or axon targeting of tmc-Gal4–positive neurons (Fig. S4), indicating that TMC protein might participate in mechanotransduction rather than neural development. Class I da neurons and bd neurons extend their dendrites along the anterior–posterior body axis, potentially facilitating their sensitivity to body contraction and relaxation during locomotion. To test if they could sense body-wall deformations in a manner that requires tmc gene function, we performed Ca2+ imaging of the axon terminals of the tmc-expressing neurons inside the ventral nerve cord (VNC) of larvae with or without the loss-of-function mutation tmcGal4. The Ca2+ level of these axon terminals was monitored while the posterior portion of the body that contains the corresponding tmc-expressing cell bodies was bent to an angle of at least 45 degrees (Fig. 4A). In the control animals, tmc-Gal4–positive neurons were sensitive to body curvature, as the Ca2+ level was elevated by abdominal bending (Fig. 4 B and C). This response was significantly reduced in the tmc mutant larvae (Fig. 4 B and C). Drosophila TMC appears to play a role in the mechanotransduction of the class I da neurons and bd neurons that serve as proprioceptors during larval locomotion. However, heterologous expression of Drosophila TMC in S2 cells did not yield mechanosensitive channel activity (Fig. S5). Thus, it remains to be determined whether Drosophila TMC and/or other as-yet-unidentified channel proteins fulfill the function of mechanosensitive channels for proprioception in larval locomotion.

Fig. S4.

Dendrite morphology of class I da neurons and axon projection of tmc-positive neurons in ventral nerve cord. Neither (A) dendrite morphology of class I da neurons nor (B) axon projection of tmc-positive neurons in ventral nerve cord shows obvious defects in tmc mutant or tmc rescue flies.

Fig. 4.

Mechanosensitive calcium responses in the axon terminals of TMC-expressing neurons. (A) Experimental setup for imaging bending-evoked calcium signals in the axon terminals of TMC-expressing neurons. Bending was evoked using a glass probe. (B) Abdominal bending-evoked calcium signals in wild-type larvae and tmc mutant larvae. There is a GCaMP signal background difference between tmc-Gal4 and tmcGal4 due to the different expression levels between them. (C) Statistical analysis of the calcium responses in wild-type and tmc mutant larvae. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used to test the difference between wild-type w1118 and tmcGal4. ***P < 0.001. n ≥ 9.

Fig. S5.

Example traces of electrophysiological recordings from cultured S2 cells transfected with NOMPC or Drosophila TMC, documenting responses to mechanical stimuli in the former but not the latter.

Functional Conservation Between Drosophila TMC and Mammalian TMC Proteins.

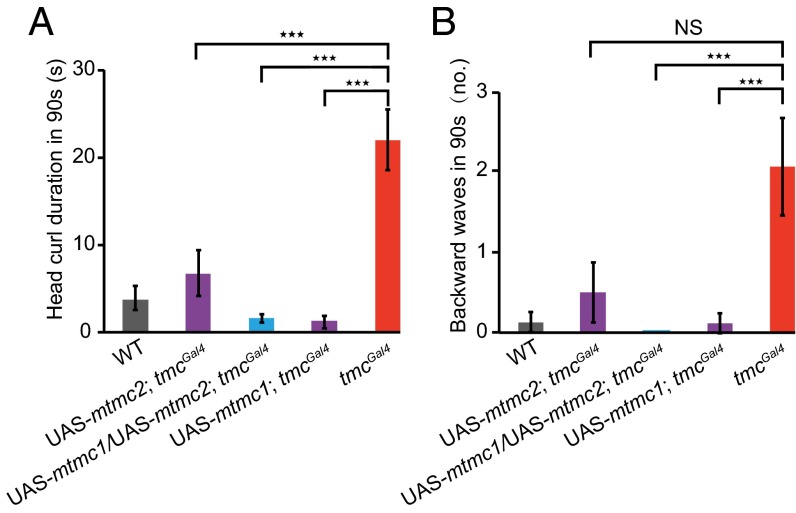

As Drosophila TMC is the only fly homolog for mammalian TMC proteins (21, 34), we asked whether mammalian TMC proteins could functionally complement the tmc mutant defects in larval locomotion. To answer this question, we expressed mouse TMC1 and/or TMC2 in tmcGal4-labeled neurons of tmc mutant larvae and examined their locomotion behavior. Intriguingly, we found that expression of both mouse TMC1 and TMC2 could fully rescue the behavioral defects due to loss of Drosophila tmc function (Fig. 5 A and B). In light of the proposal that TMC1 and TMC2 might form heteromers to function as channels (21, 34), it is noteworthy that expressing either mouse TMC1 or TMC2 alone could also fully or partially rescue the behavioral defects (Fig. 5 A and B). Hence, mammalian TMC1 and TMC2 seem able to recapitulate the proprioceptive roles of Drosophila TMC.

Fig. 5.

Mammalian TMC1 and TMC2 rescue locomotion defects in tmc mutants. (A) Head curl duration (in 90 s) and (B) backward wave numbers (in 90 s) of wild-type, UAS-mtmc2; tmcGal4, UAS-mtmc1/UAS-mtmc2; tmcGal4, and UAS-mtmc1; tmcGal4 larvae are significantly less than those of tmcGal4 larvae. One-way ANOVA was used to test for the statistical significance of the differences, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. ***P < 0.001. NS, not significant. n ≥ 8.

Discussion

Larval Locomotion Pattern Is Regulated by tmc That Is Expressed in Class I and Class II da Neurons and bd Neurons.

Proprioception is vital for animals to control their locomotion behavior, although the underlying mechanisms remain to be worked out in Drosophila and other animals (11). Here we report that the tmc gene contributes to proprioception and sensory feedback for normal forward crawling behavior in Drosophila larvae. We found that tmc is expressed in Drosophila larval sensory neurons (Fig. 2). Our behavioral and calcium imaging studies indicate that Drosophila TMC plays an important role in proprioception and regulation of crawling behavior (Figs. 3 and 4). Moreover, behavioral defects due to loss of tmc function in Drosophila were rescued by expressing mammalian TMC proteins, indicative of an evolutionarily conserved function (Fig. 5).

Differential Functions of Different Sensory Neurons in Regulating Locomotion.

Several types of body-wall sensory neurons appear to play a role in the larval locomotion regulation. Silencing Cho neurons results in increased frequency and duration of turning and reduced duration of linear locomotion (5), a phenotype similar to that caused by tmc mutation, suggesting that the Cho neurons and the tmc-expressing neurons might converge to the same motor output pathway. Interestingly, blocking class IV da neurons produces an opposite phenotype—fewer turns (6). Given that the central projection of class IV da neurons in the VNC is distinct from that of class I da neurons and bd neurons (45), it will be interesting to see how they regulate the same behavior in opposing manners.

Different neurons might use different mechanosensitive ion channels in coordinating proprioceptive cues, similar to what has been found in the touch-sensitive neurons. The TRPN channel NOMPC functions in class III da neurons to mediate gentle touch sensation (13) whereas the DEG/ENaC ion channels PPK and PPK26, the TRP channel Painless, and Piezo function in class IV da neurons to mediate mechanical nociception (10, 20, 46–48). As to proprioception, chordotonal organs, class I and class IV da neurons and bd neurons may all contribute to proprioception to regulate larval locomotion behavior (5–8, 10). It is reported that NOMPC is expressed in class I da neurons and bd neurons, and mutations of NOMPC cause prolonged stride duration and reduced crawling speed of mutant larvae (9). In contrast, the DEG/ENaC ion channels PPK and PPK26 function in class IV da neurons to modulate the extent of linear locomotion; reduction of these channel functions leads to decreased turning frequency and enhanced directional crawling (6, 10).

Evolutionary Conservation of TMC Functions.

Drosophila TMC protein exhibits sequence conservation with TMC family members in other species in the putative transmembrane domains, although it is much larger than its mouse or human homologs. It is of interest to determine whether the Drosophila TMC functions encompass a combination of functions of its mammalian homologs.

Among eight tmc genes in human and mice, tmc1 and tmc2 are found to be required for sound transduction in the hair cells of the inner ear (21, 30, 32–34, 49). However, these genes are very broadly expressed (30), so it is possible that they might also function in other tissues. In light of our finding that Drosophila TMC functions in sensory neurons to regulate locomotion and mouse TMC1 or TMC2 functionally rescue the fly mutant phenotype, it will be interesting to test whether TMC1 and TMC2 have similar functions in addition to their involvement in hearing. Our work indicates that the Drosophila tmc gene participates in proprioception. Whether mammalian tmc genes, including tmc1 and tmc2, participate in proprioception is an interesting open question.

In contrast to tmc1 and tmc2 in mammals and the Drosophila tmc gene, the tmc-1 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans was reported to contribute to high sodium sensation in ASH polymodal avoidance neurons, in which TMC-1 ion channels could be activated by high concentrations of extracellular sodium salts and permeate cations (35). It will be of interest to explore the potential roles of tmc genes in various species in mechanosensation or osmosensation.

How mammalian TMC1 and TMC2 function in sound transduction is still not fully understood, and whether they are the pore-forming channel subunits is under debate (50, 51). It remains to be shown whether TMC1 and TMC2 can yield channel activities in heterologous expression systems (52, 53), and they likely require other proteins for their function in mechanotransduction (54–56). We have attempted to ectopically express the Drosophila tmc gene product in a variety of heterologous systems. However, no obvious mechanosensitive currents could be detected when these cells are exposed to mechanical stimuli (Fig. S5). One possibility is that the Drosophila TMC protein fails to be trafficked to plasma membrane in the expression system that we used. Alternatively, additional components are required to form a mechanosensitive complex as gating of certain mechanogated ion channels such as NOMPC (57) might require interactions of ion channels with extracellular matrix and/or intracellular cytoskeleton. Analyses of Drosophila tmc gene functions in larval locomotion regulation in this study, and in other future behavioral studies, may provide an opportunity to search for additional components that are necessary for the function of TMC proteins.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks and Genetics.

Wild-type (w1118) and UAS-tmc-RNAi flies (Vienna Drosophila Resource Center stock no. 42558) were used (58). For behavioral assays, flies were cultured in an incubator in 12-h dark/light cycles. Behavioral tests were performed blind to genotypes.

Molecular Cloning and Generation of Transgenic Flies.

UAS-tmc-attB was generated by amplifying the tmc-coding sequence via RT-PCR and inserting the coding sequence into the pUAST-attB vector. P{nos-phiC31\int.NLS}X and P{CaryP}attP40 flies were used as the hosts for the transgenic insertion on the second chromosome. For UAS flies carrying mouse tmc genes, P{nos-phiC31\int.NLS}X, P{CaryP}attP40, and M{vas-int.Dm}ZH-2A, PBac{y[+]-attP-9A}VK00005 flies were used as the hosts for the transgenic insertion on the second and third chromosomes, respectively. UAS-mtmc1 and UAS-mtmc2 fly insertions were confirmed with PCR that detects a fraction of the tmc CDS. The tmc1 and tmc2 clones are a gift from Andrew Griffith, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorder, Bethesda. The tmc-Gal4 construct was generated by amplifying the Drosophila tmc promoter region via PCR (forward primer: ACGGTGGAATCCTGTTTGGTGA; reverse primer: CCTGCCTCGCTGTCCTTTGTAGA) and then cloning into the BamHI site of the pCasper-Aug-Gal4 vector. Transgenic flies were generated by P-element–mediated germ-line transformations.

Mutagenesis.

The tmcGal4 mutant fly was generated by ends-out homologous recombination (37). The 5′ and 3′ homologous arms of tmc were amplified from w1118 flies by PCR cloning and cloned into pw35-Gal4 vectors using the pEASY-Uni Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (Beijing TransGen Biotech Co.). Mutagenesis was performed as previously described (37, 48).

Antibodies and Immunostaining.

Antibody generation.

The peptide containing the last 23 amino acids (1909–1932: CDPRSASPEPTVNIIRIDIENEHEK) was injected into rabbit for antibody generation (YenZym antibody). The antiserum was affinity-purified to obtain the antibody for Drosophila TMC protein.

S2 cell staining.

S2 cells were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were blocked with 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibody [rabbit anti-TMC (1:200; YenZym Antibodies)] for 2 h and secondary antibody (Alexa 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG 1:200; Invitrogen) for 1 h. After washing briefly, cells were mounted on coverslip for imaging.

Fly brain whole-mount staining.

The whole brains were dissected out from Cha-Gal4; UAS-tmc-GFP flies and fixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA for 30 min at 4 °C. The brains were blocked with 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibody [rabbit anti-TMC (1:200; YenZym Antibodies)] overnight at 4 °C and with secondary antibody (Alexa 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG 1:200; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing briefly, brains were mounted on a coverslip for imaging.

Larval neuron staining.

Larval body-wall neuron immunohistochemical staining was performed as reported previously (59), except that the mounting medium used was VectaShield (Vector Laboratories). The filleted larvae were fixed for 20 min at room temperature (RT) and blocked with blocking buffer for 1 h RT. The samples were then incubated in blocking buffer containing Drosophila TMC antibody (1:300) for 2 h RT and after washing with secondary antibody for 2 h RT. Slides were imaged on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope using an oil immersion 40× objective.

Behavioral Assays.

The locomotion assay was performed similarly as previously described (5, 10). Videotaped locomotion behavior was analyzed offline using the Noldus software. Dislike turning behavior and head curl behavior duration were counted when the head of the larvae curled to the left, right, or up and its abdomen remained still. Backward locomotion numbers were counted when there was at least one backward wave of the whole body.

Calcium Imaging.

A wandering third instar larva was picked up and rinsed with water. The larva was then mounted on a glass slide with the ventral side up. A glass slip was pressed on the anterior part of the larval body to reduce movement, and only the posterior segments were exposed to mechanical stimulation. A glass probe was used to push the larval body laterally to achieve a certain degree. Once the larval body achieved the certain degree, the glass probe was released. The imaging data were acquired in a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. The newly available genetically coded calcium indicator GCaMP6f was used to measure the calcium signal. GCaMP6f was excited by 488-nm laser, and the fluorescent signals were collected as projections at a frame rate of about 8 Hz. The calcium signal was continuously collected before, during, and after the bending stimulation. The average GCaMP6f signal from the first 3 s before stimulus was taken as F0, and ΔF/F0 was calculated for each data point.

S2 Cell Transfection and Electrophysiological Recording.

S2 cell transfection, electrophysiological recording, and mechanical stimulation were performed as previously described (13). Briefly, Drosophila S2 cells were cultured at 25 °C in Schneider’s medium with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. S2 cells were transfected with an Effectene kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the product protocol. pUAST-tmc-GFP was cotransfected with pActin-Gal4. Electrophysiological recording was carried out 24–48 h after transfection. The bath solution contained 10 mM Hepes and 140 mM sodium methanesulfonate or 140 mM potassium methanesulfonate. The pipette solution contained 10 mM Hepes and 140 mM potassium Gluconic acid/140 mM cesium methanesulfonate. A glass probe or the recording pipette was used to give a mechanical stimulation or a negative/positive pressure, respectively. Movement steps of the glass probe were triggered and controlled by a Piezo amplifier or a Sutter MP285 manipulator. Pressure steps with a 10 mm⋅Hg increment were applied via a High Speed Pressure Clamp (HSPC, ALA-scientific), which was controlled and triggered by the pClamp software and Master-8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew Griffith (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorder) for mouse tmc clones; Dr. Craig Montell (University of California, Santa Barbara) for the pw35-Gal4 plasmids; the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center for UAS-tmc-RNAi fly stock; Susan Younger, Sandra Barbel, and Margret Winkler for technical support; Ulrich Müller and Bo Zhao (The Scripps Research Institute) for suggestions; and members of the Z.W. laboratory, L.Y.J. laboratory, D.F.E. laboratory, and M.C.G. laboratory for discussion. This work was supported by DFG Grants SFB 889 A1 and GO 1092/1-2 (to M.C.G.); a BRAINseed award (to Y.N.J.); NIH Grants R37NS040929 and 5R01MH084234 (to Y.N.J.) and DC004848 (to D.F.E.); the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant XDB02010005 (to Z.W.); and China 973 Project Grant 2011CBA0040 (to Z.W.). L.Y.J. and Y.N.J. are investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1606537113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hasan Z. Role of proprioceptors in neural control. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2(6):824–829. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90140-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz V. Proprioception and locomotor disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(10):781–790. doi: 10.1038/nrn939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1651–1697. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kernan MJ. Mechanotransduction and auditory transduction in Drosophila. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454(5):703–720. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caldwell JC, Miller MM, Wing S, Soll DR, Eberl DF. Dynamic analysis of larval locomotion in Drosophila chordotonal organ mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(26):16053–16058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535546100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ainsley JA, et al. Enhanced locomotion caused by loss of the Drosophila DEG/ENaC protein Pickpocket1. Curr Biol. 2003;13(17):1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes CL, Thomas JB. A sensory feedback circuit coordinates muscle activity in Drosophila. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35(2):383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song W, Onishi M, Jan LY, Jan YN. Peripheral multidendritic sensory neurons are necessary for rhythmic locomotion behavior in Drosophila larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):5199–5204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700895104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng LE, Song W, Looger LL, Jan LY, Jan YN. The role of the TRP channel NompC in Drosophila larval and adult locomotion. Neuron. 2010;67(3):373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorczyca DA, et al. Identification of Ppk26, a DEG/ENaC channel functioning with Ppk1 in a mutually dependent manner to guide locomotion behavior in Drosophila. Cell Reports. 2014;9(4):1446–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmas P, Hao J, Rodat-Despoix L. Molecular mechanisms of mechanotransduction in mammalian sensory neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(3):139–153. doi: 10.1038/nrn2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang L, Gao J, Schafer WR, Xie Z, Xu XZS. C. elegans TRP family protein TRP-4 is a pore-forming subunit of a native mechanotransduction channel. Neuron. 2010;67(3):381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan Z, et al. Drosophila NOMPC is a mechanotransduction channel subunit for gentle-touch sensation. Nature. 2013;493(7431):221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature11685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong J, Wang Q, Wang Z. NOMPC is likely a key component of Drosophila mechanotransduction channels. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38(1):2057–2064. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Hagan R, Chalfie M, Goodman MB. The MEC-4 DEG/ENaC channel of Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons transduces mechanical signals. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatzigeorgiou M, et al. Specific roles for DEG/ENaC and TRP channels in touch and thermosensation in C. elegans nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(7):861–868. doi: 10.1038/nn.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geffeney SL, et al. DEG/ENaC but not TRP channels are the major mechanoelectrical transduction channels in a C. elegans nociceptor. Neuron. 2011;71(5):845–857. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coste B, et al. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330(6000):55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coste B, et al. Piezo proteins are pore-forming subunits of mechanically activated channels. Nature. 2012;483(7388):176–181. doi: 10.1038/nature10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SE, Coste B, Chadha A, Cook B, Patapoutian A. The role of Drosophila Piezo in mechanical nociception. Nature. 2012;483(7388):209–212. doi: 10.1038/nature10801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan B, et al. TMC1 and TMC2 are components of the mechanotransduction channel in hair cells of the mammalian inner ear. Neuron. 2013;79(3):504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honoré E. The neuronal background K2P channels: Focus on TREK1. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(4):251–261. doi: 10.1038/nrn2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alloui A, et al. TREK-1, a K+ channel involved in polymodal pain perception. EMBO J. 2006;25(11):2368–2376. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilius B, Honoré E. Sensing pressure with ion channels. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35(8):477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sukharev SI, Blount P, Martinac B, Blattner FR, Kung C. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 1994;368(6468):265–268. doi: 10.1038/368265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tavernarakis N, Shreffler W, Wang S, Driscoll M. unc-8, a DEG/ENaC family member, encodes a subunit of a candidate mechanically gated channel that modulates C. elegans locomotion. Neuron. 1997;18(1):107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Feng Z, Sternberg PW, Xu XZS. A C. elegans stretch receptor neuron revealed by a mechanosensitive TRP channel homologue. Nature. 2006;440(7084):684–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidi S, Friedrich RW, Nicolson T. NompC TRP channel required for vertebrate sensory hair cell mechanotransduction. Science. 2003;301(5629):96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1084370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo SH, et al. Piezo2 is the principal mechanotransduction channel for proprioception. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(12):1756–1762. doi: 10.1038/nn.4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurima K, et al. Dominant and recessive deafness caused by mutations of a novel gene, TMC1, required for cochlear hair-cell function. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):277–284. doi: 10.1038/ng842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keats BJ, et al. The deafness locus (dn) maps to mouse chromosome 19. Mamm Genome. 1995;6(1):8–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00350886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurima K, Yang Y, Sorber K, Griffith AJ. Characterization of the transmembrane channel-like (TMC) gene family: Functional clues from hearing loss and epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Genomics. 2003;82(3):300–308. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keresztes G, Mutai H, Heller S. TMC and EVER genes belong to a larger novel family, the TMC gene family encoding transmembrane proteins. BMC Genomics. 2003;4(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawashima Y, et al. Mechanotransduction in mouse inner ear hair cells requires transmembrane channel-like genes. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(12):4796–4809. doi: 10.1172/JCI60405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatzigeorgiou M, Bang S, Hwang SW, Schafer WR. tmc-1 encodes a sodium-sensitive channel required for salt chemosensation in C. elegans. Nature. 2013;494(7435):95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong WJ, Golic KG. Ends-out, or replacement, gene targeting in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(5):2556–2561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535280100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moon SJ, Lee Y, Jiao Y, Montell C. A Drosophila gustatory receptor essential for aversive taste and inhibiting male-to-male courtship. Curr Biol. 2009;19(19):1623–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vosshall LB. Olfaction in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10(4):498–503. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palka J, Malone MA, Ellison RL, Wigston DJ. Central projections of identified Drosophila sensory neurons in relation to their time of development. J Neurosci. 1986;6(6):1822–1830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-06-01822.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cole ES, Palka J. The pattern of campaniform sensilla on the wing and haltere of Drosophila melanogaster and several of its homeotic mutants. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;71(Oct):41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foelix RF, Stocker RF, Steinbrecht RA. Fine structure of a sensory organ in the arista of Drosophila melanogaster and some other dipterans. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;258(2):277–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00239448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarman AP. Studies of mechanosensation using the fly. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(10):1215–1218. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.10.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green CH, Burnet B, Connolly KJ. Organization and patterns of inter specific and intraspecific variation in the behavior of Drosophila larvae. Anim Behav. 1983;31(Feb):282–291. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang JW, et al. Morphometric description of the wandering behavior in Drosophila larvae: Aberrant locomotion in Na+ and K+ channel mutants revealed by computer-assisted motion analysis. J Neurogenet. 1997;11(3-4):231–254. doi: 10.3109/01677069709115098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grueber WB, et al. Projections of Drosophila multidendritic neurons in the central nervous system: Links with peripheral dendrite morphology. Development. 2007;134(1):55–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.02666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tracey WD, Jr, Wilson RI, Laurent G, Benzer S. painless, a Drosophila gene essential for nociception. Cell. 2003;113(2):261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong L, Hwang RY, Tracey WD. Pickpocket is a DEG/ENaC protein required for mechanical nociception in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2010;20(5):429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo Y, Wang Y, Wang Q, Wang Z. The role of PPK26 in Drosophila larval mechanical nociception. Cell Reports. 2014;9(4):1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vreugde S, et al. Beethoven, a mouse model for dominant, progressive hearing loss DFNA36. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):257–258. doi: 10.1038/ng848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim KX, et al. The role of transmembrane channel-like proteins in the operation of hair cell mechanotransducer channels. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142(5):493–505. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beurg M, Kim KX, Fettiplace R. Conductance and block of hair-cell mechanotransducer channels in transmembrane channel-like protein mutants. J Gen Physiol. 2014;144(1):55–69. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201411173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holt JR, Pan B, Koussa MA, Asai Y. TMC function in hair cell transduction. Hear Res. 2014;311:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawashima Y, Kurima K, Pan B, Griffith AJ, Holt JR. Transmembrane channel-like (TMC) genes are required for auditory and vestibular mechanosensation. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467(1):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1582-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiong W, et al. TMHS is an integral component of the mechanotransduction machinery of cochlear hair cells. Cell. 2012;151(6):1283–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao B, et al. TMIE is an essential component of the mechanotransduction machinery of cochlear hair cells. Neuron. 2014;84(5):954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maeda R, et al. Tip-link protein protocadherin 15 interacts with transmembrane channel-like proteins TMC1 and TMC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(35):12907–12912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402152111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang W, et al. Ankyrin repeats convey force to gate the NOMPC mechanotransduction channel. Cell. 2015;162(6):1391–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dietzl G, et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448(7150):151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grueber WB, Jan LY, Jan YN. Tiling of the Drosophila epidermis by multidendritic sensory neurons. Development. 2002;129(12):2867–2878. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.