Abstract

Biliary atresia is the most common cause of end-stage liver disease and liver cirrhosis in children, and the leading indication for liver transplantation in the paediatric population. There is no cure for biliary atresia; however, timely diagnosis and early infant age at surgical intervention using the Kasai portoenterostomy optimize the prognosis. Late referral is a significant problem in Canada and elsewhere. There is also a lack of standardized care practices among treating centres in this country. Biliary atresia registries currently exist across Europe, Asia and the United States. They have provided important evidence-based information to initiate changes to biliary atresia care in their countries with improvements in outcome. The Canadian Biliary Atresia Registry was initiated in 2013 for the purpose of identifying best standards of care, enhancing public education, facilitating knowledge translation and advocating for novel national public health policy programs to improve the outcomes of Canadian infants with biliary atresia.

Keywords: Biliary atresia, Databases, Delivery of Health Care, Paediatric liver disease, Registries

Abstract

L’atrésie des voies biliaires est la principale cause d’insuffisance hépatique terminale et de cirrhose chez les enfants, et la première indication de transplantation du foie au sein de la population d’âge pédiatrique. Aucun traitement ne guérit l’atrésie des voies biliaires, mais un diagnostic rapide et le jeune âge du nourrisson au moment de l’intervention chirurgicale par hépato-porto-entérostomie de Kasai optimisent le pronostic. L’orientation tardive vers un spécialiste constitue un problème important au Canada et ailleurs. Par ailleurs, il n’existe pas de protocole de soins standardisés dans les centres de traitement du pays. On trouve des registres d’atrésie des voies biliaires en Europe, en Asie et aux États-Unis, lesquels ont fourni de l’information importante fondée sur des données probantes pour susciter des changements aux soins de cette affection dans ces pays et favoriser une amélioration des résultats. Le Registre canadien d’atrésie des voies biliaires a été créé en 2013 pour définir les meilleures normes de soins, améliorer l’éducation publique, favoriser le transfert des connaissances et prôner de nouveaux programmes de politiques en santé publique en vue d’améliorer le sort des nourrissons canadiens présentant une atrésie des voies biliaires.

Biliary atresia (BA) is the most frequent cause of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and liver disease-related death in children, and the leading indication for liver transplantation in the paediatric population, accounting for 75% of liver transplants in children <2 years of age (1). While not an inherited condition, BA is a congenital disease caused by a fibrosclerosing obliterative lesion of the large bile ducts that progresses uniquely in the neonatal period. In Canada, the incidence of BA is one in 19,000 live births (2), a rate similar to that in Western Europe but lower than in Asia (one in 7000 to one in 9000 live births [3,4]). The condition manifests in the first weeks after birth with persistent jaundice and pale acholic stools due to a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in otherwise healthy and thriving neonates. Several phenotypes for BA have been recently identified: 70% to 95% of cases have no other anomalies (isolated BA) (2,5–9); 5% to 15% have BA in association with structural malformations including polysplenia and situs inversus (2,5–9); 5% to 10% have BA with a cystic dilation of the common bile duct not infrequently identified on prenatal ultrasonography (cystic BA) (1,5); and approximately 10% have BA associated with cytomegalovirus infection (10).

There is no cure for BA. However, early recognition with urgent referral is currently the best prognostic variable associated with outcomes. The current standard of BA care, regardless of phenotype, is sequential surgical management with an initial hepatic portoenterostomy (Kasai procedure [KP]), followed by liver transplantation for cases that progress to end-stage liver disease. Left untreated, all cases of BA result in death by three years of age (11).

The Canadian Biliary Atresia Registry (CBAR) is a new data collection project that will prospectively follow the assessment, management and outcomes of all BA patients nationally, with the goal of evaluating and improving practices in BA care. CBAR is a national collaboration between the Canadian Association of Pediatric Surgeons and the Canadian Pediatric Hepatology Research Group, the two principal associations of health care professionals involved in the management of BA patients in Canada. CBAR also includes representation from families with children diagnosed with BA and adolescent BA patients.

THE CHALLENGE OF LATE REFERRAL FOR BA

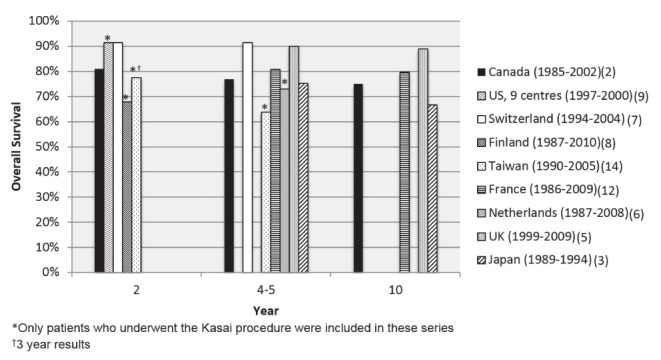

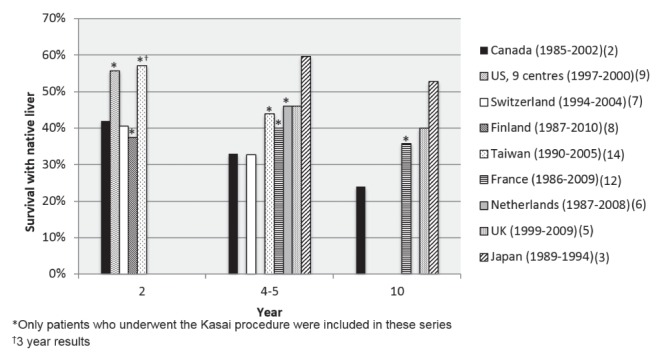

The most important and well established prognostic factor influencing the rate of post-KP patient survival without liver transplant (native liver survival) is patient age at the time of KP: the older the patient is at the time of KP, the less favourable their long-term native liver survival (2,3,6,7,12). In Canada, the best rate for long-term native liver outcome, 49% at 10 years, was observed in infants who underwent KP at <30 days of age (2). In contrast, those undergoing their KP at >90 days of age had significantly worse four- and 10-year native liver survival (23% and 15%, respectively) (2). Yet, the median age at the time of KP is 65 days in Canada, with almost 20% of cases having ‘late referral’ and untimely surgical intervention after 90 days of age (2). Long-term native liver survival rates for BA in Canada would appear to be lower than the rates observed in Western Europe and Asia (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1).

Overall survival of patients diagnosed with biliary atresia according to country. UK United Kingdom; US United States

Figure 2).

Patient survival with native liver according to country. UK United Kingdom; US United States

In Canada, all cases of BA are managed at highly specialized university-based paediatric hospitals once they are recognized. However, the approach to BA care among centres is not standardized, with variations in diagnostic workup and postoperative management (13). Moreover, there has been no formal attempt in Canada to centralize the care of BA patients or operative procedures for BA, either within centres or on a national level. Centralization has occurred in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, and the most recent reports suggest that there may be an improvement in outcomes (5); however, more long-term data are needed. While a recent study did not find a significant difference in outcomes among Canadian centres managing different numbers of cases (13), the overall numbers are small and additional data are needed to determine whether caseload per centre is related to long-term outcomes.

Another issue in Canada is the lack of standardized postnatal screening for BA and educational policies for primary care physicians to promote earlier referral of infants with persistent hyperbilirubinemia that could represent BA and facilitate more timely surgical intervention. Similar to elsewhere in the world, there are several reasons why ‘late’ referral and delayed diagnosis exist for BA in Canada. First, BA is a rare disease and few primary care providers will see even one case in their career. Second, neonatal jaundice is a very common problem for most newborns and is almost always a self-limited, nonpathological condition. The majority of breastfed newborns who experience prolonged jaundice >2 weeks after birth have benign ‘breast milk jaundice’. Given the very high likelihood that persistent jaundice in newborns is inconsequential, it is understandable that jaundice, as an early indicator of BA, is often overlooked by health care providers. Although the Canadian Paediatric Society recommends bilirubin testing in all newborns with jaundice beyond two weeks of age, this is often not done. Third, the assessment of stool colour and the monitoring for pale stools in the first few weeks of life (another clinical indicator of BA) is not a routine practice among caregivers or parents. Fourth, the routine postnatal care visit schedule in Canada is a barrier to early detection of BA. Despite recommendations for postnatal well-baby visits at one, two and four weeks, we contend that most newborn infants are seen by their health care providers at two and then at eight weeks of age, when they receive their first vaccination. By eight weeks of age, the window of opportunity for ‘timely’ referral and intervention has passed.

To overcome the issue of late referral, some countries have introduced a stool colour card screening program for BA that has demonstrated improvement in the timing of KP and long-term native liver survival (14). In Canada, British Columbia (BC) has recently introduced a home-based screening program for BA using an infant stool colour card (www.perinatalservicesbc.ca). A stool colour card is given to all parents after delivery. The card directs the parents to monitor their infant’s stool colour for the first month of life and to call a toll-free number if they detect an abnormal stool colour. The program is predicted to be highly cost effective based on a Canadian cost-effectiveness analysis (15), at an estimated $22,000 per life-year gained. Additionally, a new laboratory policy in BC and Alberta requires all laboratories that receive a requisition for bilirubin testing in a child between seven days and one year of age to test both the total and conjugated (direct) bilirubin. A flag appears on the report stating that:

...conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in infants is considered pathologic when the conjugated bilirubin is >20% of the total bilirubin. Prompt evaluation is necessary especially to assess for biliary atresia.

Other Canadian provinces have not yet introduced such policies to facilitate earlier detection and referral of infants who potentially have BA.

THE ROLE OF DATA REGISTRIES IN PAEDIATRIC HEALTH CARE DELIVERY AND ADVOCACY

Paediatricians are well aware of the impact that registries have had on improving patient outcomes. Registries collecting data on specific populations or diseases are becoming an increasingly common method of examining standards of care and disease outcomes, and promoting public health policy (16). Especially for rare diseases, registries can provide outcome information that cannot be gleaned from single-centre studies and clinical trials. While clinical trials are conducted in controlled settings, and are restricted to specific populations and timeframes, registries examine outcomes in broader populations treated in real clinical settings, often over long periods of time (16). With a national health care system, ease of data sharing between regions and lack of competition-driven patient-care systems, Canada is well-suited for the establishment of large population-based registries. Successful examples that have provided evidence to inform and advance care of paediatric patients include the Canadian Neonatal Network (17), the Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAPSNet) (18) and the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Registry (19).

BA registries

The establishment of national and regional BA registries elsewhere in the world has improved BA outcomes. In England and Wales, registry data regarding BA survival rates prompted the National Health Service to mandate that BA care be centralized to three centres in the country: London, Birmingham and Leeds (5). Subsequent registry data confirmed that native liver survival and overall patient survival at five years in the United Kingdom had significantly improved after centralization (5). Finland’s national registry also recorded significant outcome improvements following centralization of care to a single national centre in that country (8). In contrast, the French national registry has shown that outcomes are improved while maintaining a decentralized care policy provided that a strong collaborative and consultative care model is maintained among centres (12). Similar national registries exist in Japan (3), Taiwan (4), the Netherlands (6), and elsewhere across Europe (7,20) and the United States (21), although the latter is a consortium of several highly specialized centres and not a nationwide registry. In addition to evaluating patient outcomes, these registries have led to improvements in cooperation, communication, education and disease awareness among health care professionals, paraprofessionals, public policy personnel and the general public involved in BA care in their respective countries.

THE CBAR – OBJECTIVES

The CBAR project was born when a family, whose child had been operated on for BA at the Montreal Children’s Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre (Montreal, Quebec), directed a large corporate philanthropic grant to the hospital’s foundation to start the registry. The first planning meeting, held in September 2013, and funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, set the framework to initiate the project. Further funding continues to be provided by the Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation through the family’s ongoing fundraising efforts, and by the Children with Intestinal and Liver Disorders Foundation of Canada (CH.I.L.D.).

The goal of CBAR, as a population-based disease-specific cohort, is to generate critical epidemiological data regarding BA in Canada and to provide clinical data that can be used to develop evidence-informed standards of BA care. CBAR will also enhance public education and BA awareness, facilitate knowledge translation throughout the country, and advocate for public health policies and care standards to improve outcomes of children born with BA. It will analyze variations in care standards among centres to identify best practices, and it will benchmark overall Canadian outcomes against existing BA registry data worldwide. CBAR will provide invaluable feedback to inform the efficacy of differing provincial public health care policies, for example, the stool card screening program in BC and the bilirubin testing laboratory policy in BC and Alberta.

CBAR ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE AND DATA COLLECTION

The organizational structure of CBAR is modelled after the CAPSNet (www.capsnetwork.org), a successful national database established by the Canadian Association of Pediatric Surgeons in 2005. CAPSNet itself was built on the very successful Canadian Neonatal Network (www.canadianneonatalnetwork.org). The CBAR steering committee, comprising both health care professionals and laypersons, is responsible for ensuring that the registry achieves its stated goals. The committee provides guidance regarding data collection, data analysis and any related collaborative projects that emerge. It also provides direction on CBAR’s communication including the CBAR website, annual reporting and knowledge translation. The steering committee is a geographically representative group comprised of paediatric surgeons, gastroenterologists, parents and patients, representing the gamut of stakeholders invested in optimizing outcomes of patients with BA in Canada.

Each participating centre has access to its own data. As with CAPSNet, researchers interested in completing an analysis with aggregate CBAR data will submit a formal proposal to the steering committee to be vetted. The proposal is to be approved by the steering committee before any analyses will be performed. The steering committee will also review any manuscripts or presentations produced using CBAR data before submission. CBAR must be acknowledged as an author on all publications and presentations.

All 14 university-based tertiary paediatric hospital centres in Canada are participating in CBAR, effectively encompassing every patient with BA nationally to create this unique population-based registry. By autumn 2016, we anticipate that all sites will be actively entering new cases into the database, with retrospective data entry of cases identified since January 1, 2014. It is expected that the annual accrual across all sites will be between 18 and 22 patients. The registry plans to collect data for the next 10 years.

Each CBAR site has two investigators, one paediatric surgeon and one paediatric gastroenterologist, who are responsible for overseeing patient recruitment, data collection and research ethics approval. Many larger sites use a research assistant to collect and enter data into the database. At smaller sites, the site investigators may do this themselves. CBAR will follow patients from the time they are referred to the tertiary centre until they receive a liver transplant, transition to adult care or die. CBAR will collect information in the following areas: demographics, referral process, initial consultation at the tertiary centre, surgical procedure, immediate postoperative hospital stay, regular follow-up care, inpatient or outpatient events related to their BA and basic short-term outcome information on any transplants they receive.

CBAR CHALLENGES

CBAR has faced certain challenges that are common to multisite data registries and studies. Ethics agreements must be in place and renewed yearly at each of the participating sites. Research ethics requirements vary among different provinces and sites. Most require patient informed consent to be obtained, which poses unique challenges in the context of a rare disease database. Due to the small numbers that are expected to accrue each year, it is possible that refusal to participate from even one or two patients each year could statistically skew the data set. Negotiation of clinical subsite agreements that outline the rights and responsibilities of the contributing site and the coordinating site can be lengthy and can significantly delay the start of data collection.

Another challenge common to multicentre registries is the process of using the data in future analyses. Most sites require an additional ethics application each time registry data are used in a study. Because there is no centralized research ethics board in Canada, the applications must be completed individually at each site and may take several months to gain approval. Consequently, each analysis may require a significant investment of time for ethics applications before use of data.

SUMMARY

BA is the most serious paediatric liver disease, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. National BA registries have generated evidence-based data that have led to improved outcomes in their respective countries. A Canadian BA registry (www.cbar.ca) has now been established with the aim to identify best standards of BA care for children in Canada, and for patient education and advocacy. The goal of CBAR is to improve the outcomes of children affected with this devastating and uniquely paediatric liver disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hartley JL, Davenport M, Kelly DA. Biliary atresia. Lancet. 2009;374:1704–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60946-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreiber RA, Barker CC, Roberts EA, et al. Biliary atresia: The Canadian experience. J Pediatr. 2007;151:659–65. 665.e.1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nio M, Ohi R, Miyano T, et al. Five- and 10-year survival rates after surgery for biliary atresia: A report from the Japanese Biliary Atresia Registry. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YC, Chang MH, Liao SF, et al. Decreasing rate of biliary atresia in Taiwan: A survey, 2004–2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e530–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davenport M, Ong E, Sharif K, et al. Biliary atresia in England and Wales: Results of centralization and new benchmark. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1689–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vries W, de Langen ZJ, Groen H, et al. Biliary atresia in the Netherlands: Outcome of patients diagnosed between 1987 and 2008. J Pediatr. 2012;160:638–644.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wildhaber BE, Majno P, Mayr J, et al. Biliary atresia: Swiss national study, 1994–2004. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:299–307. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181633562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lampela H, Ritvanen A, Kosola S, et al. National centralization of biliary atresia care to an assigned multidisciplinary team provides high-quality outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:99–107. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.627446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shneider BL, Brown MB, Haber B, et al. A multicenter study of the outcome of biliary atresia in the United States, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2006;148:467–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zani A, Quaglia A, Hadzić N, Zuckerman M, Davenport M. Cytomegalovirus-associated biliary atresia: An aetiological and prognostic subgroup. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1739–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chitsaz E, Schreiber RA, Collet JP, Kaczorowski J. Biliary atresia: The timing needs a changin’. Can J Public Health. 2009;100:475–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03404348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chardot C, Buet C, Serinet MO, et al. Improving outcomes of biliary atresia: French national series 1986–2009. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber RA, Barker CC, Roberts EA, Martin SR, the Canadian Pediatric Hepatology Research Group Biliary Atresia in Canada: The effect of Centre Caseload Experience on Outcome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:61–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d67e5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lien TH, Chang MH, Wu JF, Chen HL, Lee HC, Chen AC. Effects of the infant stool color card screening program on 5-year outcome of biliary atresia in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2011;53:202–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.24023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber RA, Masucci L, Kaczorowski J, et al. Home-based screening for biliary atresia using infant stool colour cards: A large-scale prospective cohort study and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Med Screen. 2014;21:126–32. doi: 10.1177/0969141314542115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones S, James E, Prasad S. Disease registries and outcome research in children: Focus on lysosomal storage disorders. Pediatr Drugs. 2011;13:33–47. doi: 10.2165/11586860-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Canadian Neonatal Network The Canadian Neonatal NetworkTM. c2009. < www.canadianneonatalnetwork.org/portal> (Accessed July 16, 2015)

- 18.The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network. c2015. < www.capsnetwork.org/portal/ContactUs.aspx> (Accessed July 16, 2015)

- 19.Cystic Fibrosis Canada The Canadian CF Registry. < www.cysticfibrosis.ca/cf-care/cf-registry> (Accessed July 16, 2015)

- 20.Petersen C, Harder D, Abola Z, et al. European biliary atresia registries: Summary of a symposium. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008;18:111–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokol RJ. New North American research network focuses on biliary atresia and neonatal liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:1. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]