Abstract

Nurse-like cells (NLCs) play a central role in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) because they promote the survival and proliferation of CLL cells. NLCs are derived from the monocyte lineage and are driven toward their phenotype via contact-dependent and -independent signals from CLL cells. Because of the central role of NLCs in promoting disease, new strategies to eliminate or reprogram them are needed. Successful reprogramming may be of extra benefit because NLCs express Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) and thus could act as effector cells within the context of antibody therapy. IFNγ is known to promote the polarization of macrophages toward an M1-like state that is no longer tumor-supportive. In an effort to reprogram the phenotype of NLCs, we found that IFNγ up-regulated the M1-related markers CD86 and HLA-DR as well as FcγRIa. This corresponded to enhanced FcγR-mediated cytokine production as well as rituximab-mediated phagocytosis of CLL cells. In addition, IFNγ down-regulated the expression of CD31, resulting in withdrawal of the survival advantage on CLL cells. These results suggest that IFNγ can re-educate NLCs and shift them toward an effector-like state and that therapies promoting local IFNγ production may be effective adjuvants for antibody therapy in CLL.

Keywords: cell-cell interaction, Fc receptor, interferon, signal transduction, tumor immunology

Introduction

Nurse like cells (NLCs)3 are tumor-nurturing cells derived from CD14+ monocytes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. In vitro studies have classified NLCs as CLL-specific, tumor-associated macrophage-like cells functioning as immune regulators and also possible inducers of emerging drug resistance (1–3). It has been shown recently that, in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma, a high density of CD68+/CD163+ tumor-associated macrophages was significantly correlated with unfavorable prognosis and poor clinical outcome (4).

Given the crucial role NLCs play in CLL cell survival, a number of immune modulators have been screened for their suitability as therapy against them. Burger et al. (3) showed that SDF-1-blocking antibodies reduced the protective effects of NLCs on CLL cells. Morande et al. (5) recently showed that NLCs were susceptible to Aplidin-induced death, suggesting that its anti-tumoral effects were from targeting CLL cells and NLCs simultaneously. Schulz et al. (6) showed that treatment with lenalidomide changed the functional and phenotypic nature of NLCs by interfering with their nurturing properties.

Interferons have been widely accepted as modulators of macrophage plasticity and activation, and it is known that IFNγ is capable of promoting the differentiation of monocytic cells (7). With regard to therapeutic use, Miller et al. (8) have shown that IFNγ is beneficial for treating immune disorders such as systemic sclerosis and that it displays antitumor and antiangiogenic effects both in vitro and in vivo. IFNγ treatment has also been shown to induce antineoplastic immune responses by sensitizing tumor cells to apoptosis via up-regulation of both MHC class I and II molecules and by enhancing antitumor immune activity while decreasing M2 characteristics in immune cells (9, 10). IFNγ has been successfully used in cases of ovarian cancer, multiple myeloma (11), and bladder carcinoma and, recently, in malignant gliomas (12).

Here we examined the effects of IFNγ on the phenotype and function of NLCs. We found that IFNγ significantly increased the expression of the M1-related markers CD86 and HLA-DR as well as the phagocytic receptor FcγRI. Concurrently, the prosurvival ligand CD31 was down-regulated. Consistent with this, IFNγ-treated NLCs showed superior phagocytic ability toward both opsonized sheep RBCs (SRBCs) and rituximab-coated CLL cells as well as withdrawal of support for CLL cell survival. These results show that IFNγ can reprogram NLCs to function as immune effectors and suggest that therapies that enhance IFNγ production locally may be valuable treatments for CLL, particularly when combined with monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab.

Experimental Procedures

Patient Samples

Peripheral blood was collected from CLL patients with informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under approval from the Institutional Review Board of Ohio State University.

NLC Culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from CLL patient blood by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone Laboratories, Grand Island, NY), 2 mm l-glutamine (Invitrogen), and penicillin/streptomycin (56 units/ml, 56 μg/ml; Invitrogen). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured at high density (10 × 106 cells/ml, 2 ml/well) in 6-well tissue culture plates (Corning Costar, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 14 days to allow the development of NLCs (2, 3).

Reagents and Antibodies

TRIzol was from Invitrogen. Reverse transcriptase, random hexamers, and SYBR Green PCR mixture were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). qPCR primers were as follows: GAPDH (forward, 5′-ATTCCCTGGATTGTGAAATAGTC-3′; reverse, 5′-ATTAAAGTCACCGCCTTCTGTAG-3′), 18S RNA (forward, 5′-TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA-3′), FcγRI (CD64) (forward, 5′-GGCAAGTGGACACCACAAAGGCA-3′; reverse, 5′-GCTGGGGGTCGAGGTCGAGGTCTGAGT-3′), CD86 (forward, 5′-GGGCCGCACAAGTTTTGA-3′; reverse, 5′-GCCCTTGTCCTTGATCTGAA-3′), and CD31 (forward, 5′-ATTGCAGTGGTTATCATCGGAGTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCGTTGTTGGAGTTCAGAAGTGG-3-′). qPCR primers for HLA-DQ (Hs.PT.58.15134093), HLA-DR (Hs.PT.58.15096946), NOS-2 (Hs.PT.58.14740388), and SDF-1 (Hs.PT.58.27881121) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology (San Diego, CA).

Unconjugated F(ab')2 of 32.2 (anti-FcγRI) was from Medarex (Annandale, NJ), and FITC-conjugated F(ab')2 goat anti-mouse IgG was from Life Technologies. Anti-human CD68-FITC and anti-human HLA-DR Alexa Fluor 488 were from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Anti-human CD86-PE (phycoerythrin), anti-human CD80-PERCP (peridinin chlorophyll A protein), anti-human CD200-R-PE, and anti-human CD14-APC (allophycocyanin) were from BD Biosciences. The wheat germ agglutinin conjugates Alexa Fluor 488 and 647 were purchased from Life Technologies. Recombinant IFNγ was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Rituximab and Herceptin (Genentech, San Francisco, CA) were purchased commercially.

CLL Cell Enrichment

CLL-enriched fractions were prepared using the Rosette-Sep B cell kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Flow Cytometry Staining of Surface and Intracellular Markers

NLCs were harvested using 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen) followed by gentle scraping. After Fc receptor blockade, cells were incubated with 1 μg of surface marker antibody at 1 × 106 cells/ml for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice with FACS buffer (PBS, 0.1% sodium azide, and 2% FBS). Intracellular staining was done for CD68 using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit following the protocol of the manufacturer (BD Biosciences). An LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used for flow cytometry, and FlowJo (FlowJo, Ashland, OR) software was used for analysis.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and chloroform extraction followed by DNase (Invitrogen) treatment and reverse-transcribed, and cDNA was used for qPCR. GAPDH and 18S RNA were used for normalization. The relative copy number was calculated as 2(−ΔCt) (13).

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis assays were performed as described previously (14). Briefly, NLCs were pretreated with IFNγ or PBS for 72 h. SRBCs (Colorado Serum Co., Denver, CO) were fluorescently labeled using PKH26 dye (Sigma) according to the instructions of the manufacturer and then opsonized with anti-SRBC antibody (Sigma) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. SRBCs were mixed with NLCs, and then cells were gently pelleted by slow centrifugation and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Non-ingested SRBCs were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) at room temperature for 10 min. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Ingested RBCs were counted using fluorescence immersion oil microscopy. The phagocytic index was calculated as the total number of SRBCs ingested by 50 NLCs.

CLL Cell Survival Assay

Nurse-like cells were pretreated with 10 ng/ml IFNγ or PBS control for 72 h. Cells were counted and left overnight for adherence in quadruplicate in 96-well tissue culture plates (5 × 104/100 μl of medium). CLL cells were added at (5 × 105/100 μl) and incubated for 24 h. Non-adherent CLL B cells (100 μ ∼ 5 × 105) were harvested and stained with Annexin V FITC/propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) using the protocol of the manufacturer. Data are represented as the percentage of total live CLL cells (Annexin V FITC− propidium iodide−).

NLC Phagocytosis of CLL Cells

CLL cells were enriched as described previously, incubated with 10 μg/ml rituximab on ice for 2 h, washed with PBS, and then labeled with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (5.0 μg/ml, Life Technologies) for 10 min at room temperature. Simultaneously, NLCs were harvested, washed, and incubated with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (5.0 μg/ml, Life Technologies) for 10 min at room temperature. Following washes, co-incubations of NLCs with CLL cells for 60 min at a ratio of 1:5 (NLC:CLL) were done. Cells were then washed and fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were placed onto microscope slides with ProLong® Gold mounting solution (Thermo Scientific) and then examined using confocal microscopy.

Statistics

For NLC gene expression studies, paired two-tailed Student's t tests were used to compare untreated relative copy numbers to IFNγ-treated relative copy numbers. For the phagocytosis results, paired two-tailed Student's t tests were used to compare the mean phagocytic index control versus IFNγ-treated cells. For the inhibitor experiments, mixed-effect modeling was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). Significance was counted as p ]ltequ] 0.05.

Results

Characterization of NLCs

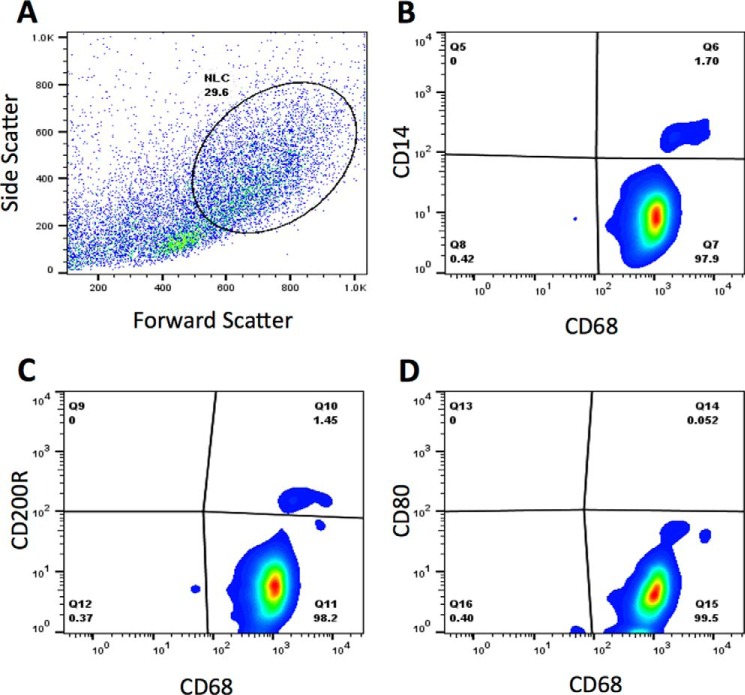

CLL-patient NLCs were derived as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and their characteristics were confirmed via flow cytometry (Figs. 1, A–D). Gating based on forward and side scatter was done in accordance with previous work (1–3) (Fig. 1A). The results showed that the cells were CD68+ and CD14dim (Fig. 1B), with some CD68+ cells also showing expression of CD200R (Fig. 1C). All cells were CD80− (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of NLCs. A–D, NLCs were generated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NLCs were analyzed using flow cytometry. Graphs show scatter (A), CD14 (B), CD200R (C), and CD80 (D) in the CD68+ population.

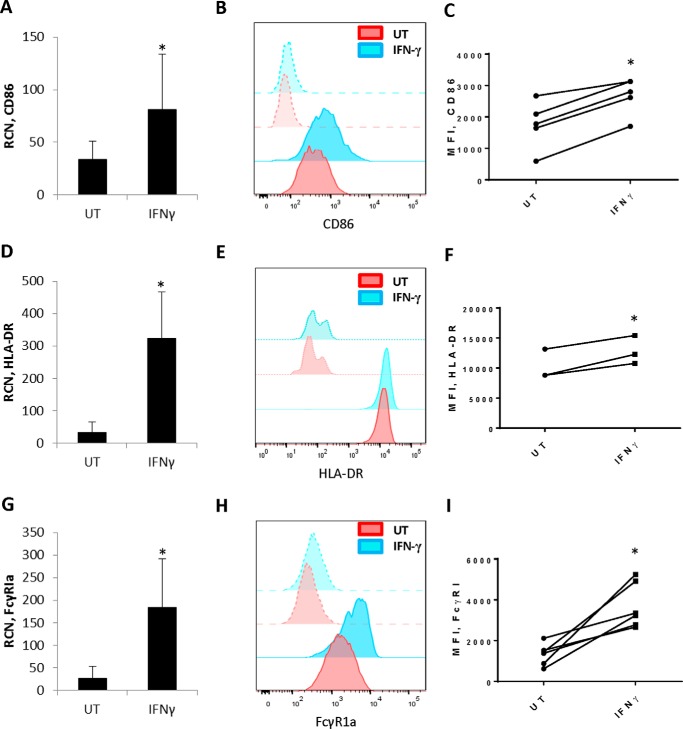

IFNγ Enhances NLC Expression of CD86, HLA-DR, and FcγRI

NLCs have been described as counterparts to tumor-associated macrophages seen within solid tumors (1, 15, 16). This led to the question of whether they could be reprogrammed away from their tumor-supportive phenotype. Because of their similarities with solid-tumor macrophages, the possibility existed that treatment with cytokines such as IFNγ (9) might be effective. To test this, we treated NLCs for 72 h with IFNγ and measured levels of the M1-related markers (17) NOS2 (nitric-oxide synthase 2), HLA-DR, and CD86. Results showed that IFNγ led to variable effects with NOS2, increasing for some donors and decreasing for others (data not shown). Transcripts for the T cell coactivator CD86 were significantly elevated (Fig. 2A), with a corresponding increase in surface expression (Fig. 2, B and C). Likewise, HLA-DR was significantly elevated at the transcriptional (Fig. 2D) as well as cell surface levels (Fig. 2, E and F) by IFNγ.

FIGURE 2.

IFNγ elicits expression of CD86, HLA-DR and FcγRIa in NLCs. NLCs were generated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NLCs were treated with or without 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 72 h. A, D, and G, qPCR done to measure CD86 (A, n = 6), HLA-DR (D, n = 4), and FcγR1 (G, n = 6). B, E, and H, NLCs were treated as above, and flow cytometry was done for CD86 (B), HLA-DR (E), and FcγRI (H). Histograms show fluorescence intensity of each respective marker. Solid red, untreated (UT); transparent red, isotype control; solid blue, IFNγ-treated, transparent blue, isotype control. Representative histograms are shown. C, F, and I, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for CD86 (C, n = 5), HLA-DR (F, n = 3), and FcγRI (I, n = 6). *, p ≤ 0.05.

We also examined FcγRI, which is the high-affinity IgG receptor and thus can play a role in antibody-mediated responses (18). This receptor has been shown to respond to IFNγ in healthy donor monocytes and macrophages (19, 20) as well as in primary acute myeloid leukemia cells (21). Results showed that treatment of NLCs with IFNγ significantly increased FcγRI transcript (Fig. 2G) and protein (Fig. 2, H and I). However, FcγRIIa, FcγRIIb, FcγRIIIa, and γ chain levels were unaffected (data not shown).

We also tested the effect of IFNγ on SDF-1 levels because this is a major protumoral factor produced by NLCs (3). However, no effect of IFNγ on SDF-1 transcript was seen (data not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that IFNγ does not effect a complete shift toward an M1 phenotype in NLCs but that it does up-regulate molecules involved with effector functions.

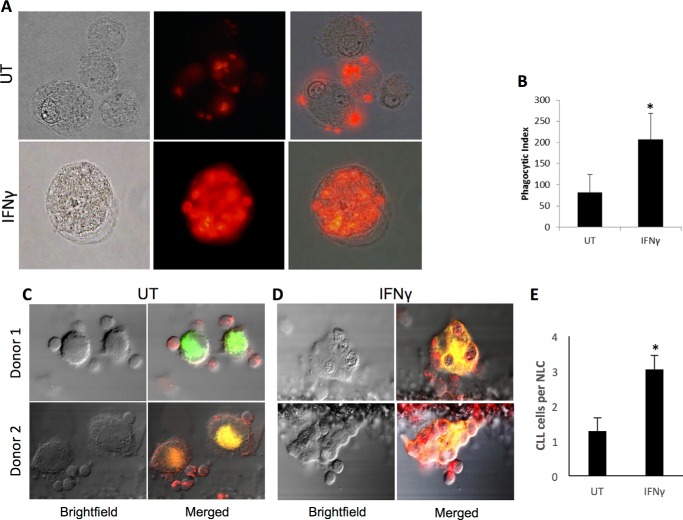

IFNγ Enhances Phagocytosis by NLCs

Because IFNγ increased expression of the high-affinity IgG receptor FcγRI, we tested the effects of IFNγ on phagocytosis. We treated NLCs with IFNγ for 72 h and then measured their ability to ingest fluorescently labeled, opsonized SRBCs. The results showed that IFNγ-treated NLCs ingested significantly more SRBCs than untreated NLCs (p = 0.034, Fig. 3A, plotted in B).

FIGURE 3.

IFNγ enhances phagocytosis by NLCs. NLCs (n = 3 donors) were treated for 72 h with or without 10 ng/ml IFNγ and used in phagocytosis assays. A, representative microscopy images of untreated (UT, top panels) and IFNγ-treated (bottom panels) cells. Shown are bright-field (left panels), fluorescence (center panels), and merged (right panels) images. B, phagocytic index of untreated versus IFNγ-treated NLCs. C—E, NLCs (n = 5 donors) were treated as above and tested for phagocytosis of CLL cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Images show untreated (C) and IFNγ-treated NLCs (D). E, the average number of CLL cells ingested by NLCs. Error bars represent standard deviation. *, p ≤ 0.05.

Next, we tested whether IFNγ-treated NLCs would be capable of phagocytosing antibody-coated CLL cells. We treated NLCs with IFNγ for 72 h as above, membrane-labeled them with fluorescent dye, and then incubated them for 1 h with membrane-labeled CLL cells that were opsonized with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, which is commonly used for the treatment of CLL. We examined phagocytosis via confocal microscopy between untreated (Fig. 3C) and IFNγ-treated (Fig. 3D) NLCs and found that IFNγ significantly increased the number of ingested CLL cells (Fig. 3E).

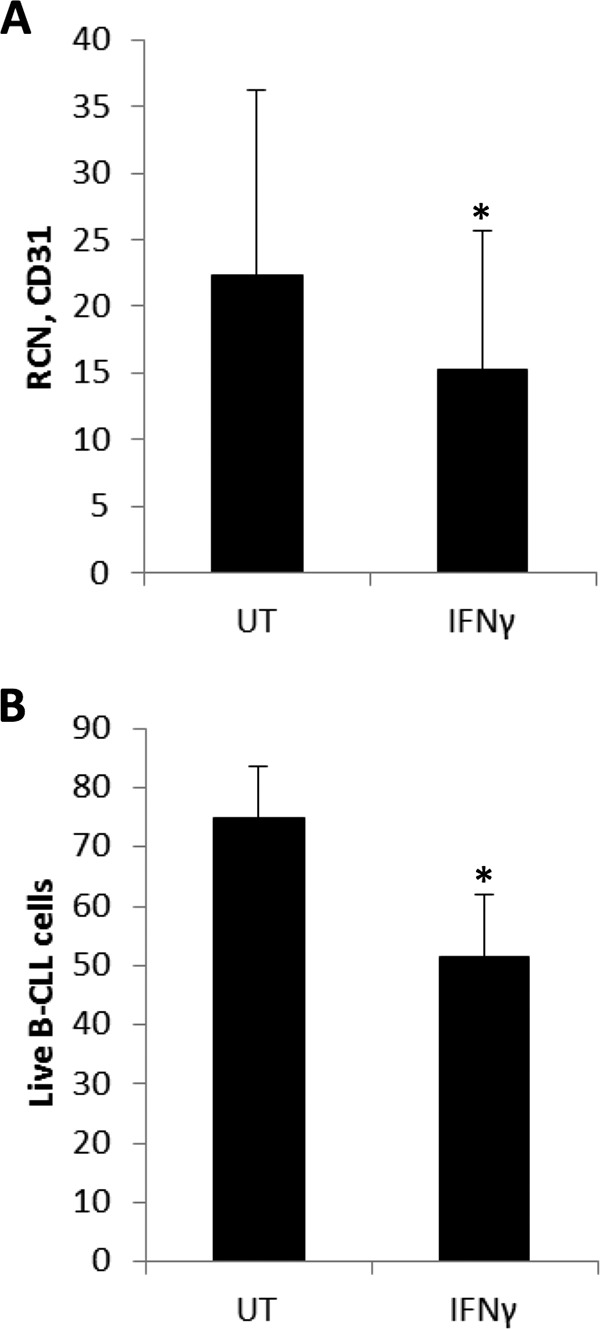

IFNγ Down-regulates CD31 and Reduces NLC-mediated Survival of CLL Cells

CD38/CD31 interactions in cooperation with CD100 promote survival of CLL cells, and it has been shown that blocking antibodies against CD31 can disrupt CLL cell survival (22). Hence, we tested the effects of IFNγ treatment on the expression of CD31 in NLCs. The results showed that 72-h treatment with IFNγ led to a significant reduction in CD31 (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

IFNγ down-regulates CD31 and reduces NLC-mediated survival of CLL cells. A, NLCs (n = 13 donors) were treated without or with 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 72 h, and CD31 was measured using qPCR. UT, untreated. B, NLCs were treated as above and then co-cultured with non-autologous CLL cells for 24 h. Annexin V FITC-propidium iodide staining was done with CLL cells, and double-negative cells were counted as live (n = 4 donors).

The above led us to test whether IFNγ-induced NLC polarization would be sufficient to interfere with NLC-dependent CLL cell survival. We treated NLCs for 72 h and then co-cultured them with CLL cells for 24 h. CLL cell survival was measured by Annexin/propidium iodide staining. The results showed that IFNγ treatment significantly reduced the survival of CLL cells within the co-cultures (Fig. 4B) despite not accelerating the death of control CLL cells in single culture (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we found that treatment of NLCs with IFNγ could reprogram them toward a more effector-like phenotype and also in such a way that they no longer supported the survival of CLL cells. IFNγ also significantly enhanced the phagocytic ability of NLCs against opsonized SRBCs as well as rituximab-coated CLL cells. These findings suggest that IFNγ could serve to improve the outcome of antibody therapy for CLL. They also support the earlier observation that NLCs resemble M2-like tumor-associated macrophages (15) because the latter have been found to respond to IFNγ (9).

In addition, these data suggest that SDF-1, although important for CLL cell survival, is by itself not sufficient. IFNγ did not significantly decrease NLC SDF-1 but did decrease CLL cell survival in NLC/CLL cultures. This is in agreement with Burger et al. (3), who found that supplementing CLL cells with SDF-1 offered some but not full protection against apoptosis. Additional survival stimuli such as CD31/CD38 interactions, along with others yet to be tested, are likely to contribute to CLL cell survival. Quantifying the full effects of IFNγ on NLCs with regard to their interactions with CLL cells will require further study.

Direct administration of IFNγ continues to be tested for conditions including macular edema, HIV, and various tumor types (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov). A synthetic version of IFNγ (Actimmune) was approved for the treatment of chronic granulomatous disease as well as to delay the progression of malignant osteopetrosis (http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm109130.htm). Our results suggest that such IFNγ administration may be beneficial against CLL as well. Within the context of antibody therapy, IFNγ would be induced in natural killer cells, which could act locally upon the NLCs. This could be further strengthened by the co-administration of agents such as IL-12 (23), CpG (24), and TLR8 agonists (25). Such co-treatment would be predicted to significantly enhance antibody-mediated clearance of CLL cells and may also inhibit the development of new NLCs. Given the importance of CD20 antibody-based therapy in prolonging survival of CLL patients, this could represent a major advance for this currently incurable disease.

Author Contributions

J. C. B., S. T., and J. P. B. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. S. G., K. F., S. E., B. F. R., and L. R. performed the experiments, collected the data, and summarized the results. X. M. analyzed and interpreted the data and contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors gave final approval to the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Huiqing Fang for assistance with culturing and sample preparation.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01-CA095426 and R01 CA162411 (to S. T. and J. C. B.) and T32 HL007946 (to B. F. R.) and by Ohio State University College of Medicine McWhinney Bridge Fund 244749 (to J. P. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- NLC

- nurse-like cell

- CLL

- chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- FcγR

- Fcγ receptor

- SRBC

- sheep RBC

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Ysebaert L., and Fournié J. J. (2011) Genomic and phenotypic characterization of nurse-like cells that promote drug resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 52, 1404–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsukada N., Burger J. A., Zvaifler N. J., and Kipps T. J. (2002) Distinctive features of “nurselike” cells that differentiate in the context of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 99, 1030–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burger J. A., Tsukada N., Burger M., Zvaifler N. J., Dell'Aquila M., and Kipps T. J. (2000) Blood-derived nurse-like cells protect chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells from spontaneous apoptosis through stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood 96, 2655–2663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marchesi F., Cirillo M., Bianchi A., Gately M., Olimpieri O. M., Cerchiara E., Renzi D., Micera A., Balzamino B. O., Bonini S., Onetti Muda A., and Avvisati G. (2015) High density of CD68+/CD163+ tumour-associated macrophages (M2-TAM) at diagnosis is significantly correlated to unfavorable prognostic factors and to poor clinical outcomes in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. 33, 110–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morande P. E., Zanetti S. R., Borge M., Nannini P., Jancic C., Bezares R. F., Bitsmans A., González M., Rodríguez A. L., Galmarini C. M., Gamberale R., and Giordano M. (2012) The cytotoxic activity of Aplidin in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is mediated by a direct effect on leukemic cells and an indirect effect on monocyte-derived cells. Invest. New Drugs 30, 1830–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schulz A., Dürr C., Zenz T., Döhner H., Stilgenbauer S., Lichter P., and Seiffert M. (2013) Lenalidomide reduces survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in primary cocultures by altering the myeloid microenvironment. Blood 121, 2503–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perussia B., Dayton E. T., Fanning V., Thiagarajan P., Hoxie J., and Trinchieri G. (1983) Immune interferon and leukocyte-conditioned medium induce normal and leukemic myeloid cells to differentiate along the monocytic pathway. J. Exp. Med. 158, 2058–2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller C. H., Maher S. G., and Young H. A. (2009) Clinical use of interferon-γ. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1182, 69–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duluc D., Corvaisier M., Blanchard S., Catala L., Descamps P., Gamelin E., Ponsoda S., Delneste Y., Hebbar M., and Jeannin P. (2009) Interferon-γ reverses the immunosuppressive and protumoral properties and prevents the generation of human tumor-associated macrophages. Int. J. Cancer 125, 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prasse A., Germann M., Pechkovsky D. V., Markert A., Verres T., Stahl M., Melchers I., Luttmann W., Müller-Quernheim J., and Zissel G. (2007) IL-10-producing monocytes differentiate to alternatively activated macrophages and are increased in atopic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 464–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergsagel D. E., von Wussow P., Alexanian R., Avvisati G., Bataille R., Barlogie B., Borden E., Caligaris-Cappio F., Deicher H., and Durie B. G. (1990) Interferons in the treatment of multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 8, 1444–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kane A., and Yang I. (2010) Interferon-γ in brain tumor immunotherapy. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 21, 77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gavrilin M. A., Bouakl I. J., Knatz N. L., Duncan M. D., Hall M. W., Gunn J. S., and Wewers M. D. (2006) Internalization and phagosome escape required for Francisella to induce human monocyte IL-1β processing and release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 141–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shah P., Fatehchand K., Patel H., Fang H., Justiniano S. E., Mo X., Jarjoura D., Tridandapani S., and Butchar J. P. (2013) Toll-like receptor 2 ligands regulate monocyte Fcγ receptor expression and function. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 12345–12352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giannoni P., Pietra G., Travaini G., Quarto R., Shyti G., Benelli R., Ottaggio L., Mingari M. C., Zupo S., Cutrona G., Pierri I., Balleari E., Pattarozzi A., Calvaruso M., Tripodo C., et al. (2014) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia nurse-like cells express hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-MET) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and display features of immunosuppressive type 2 skewed macrophages. Haematologica 99, 1078–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boissard F., Fournié J. J., Laurent C., Poupot M., and Ysebaert L. (2015) Nurse like cells: chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated macrophages. Leuk. Lymphoma 56, 1570–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mosser D. M. (2003) The many faces of macrophage activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Graziano R. F., and Fanger M. W. (1987) Fc γ RI and Fc γ RII on monocytes and granulocytes are cytotoxic trigger molecules for tumor cells. J. Immunol. 139, 3536–3541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guyre P. M., Morganelli P. M., and Miller R. (1983) Recombinant immune interferon increases immunoglobulin G Fc receptors on cultured human mononuclear phagocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 72, 393–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perussia B., Dayton E. T., Lazarus R., Fanning V., and Trinchieri G. (1983) Immune interferon induces the receptor for monomeric IgG1 on human monocytic and myeloid cells. J. Exp. Med. 158, 1092–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Notter M., Ludwig W. D., Bremer S., and Thiel E. (1993) Selective targeting of human lymphokine-activated killer cells by CD3 monoclonal antibody against the interferon-inducible high-affinity Fc γ RI receptor (CD64) on autologous acute myeloid leukemic blast cells. Blood 82, 3113–3124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deaglio S., Vaisitti T., Bergui L., Bonello L., Horenstein A. L., Tamagnone L., Boumsell L., and Malavasi F. (2005) CD38 and CD100 lead a network of surface receptors relaying positive signals for B-CLL growth and survival. Blood 105, 3042–3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parihar R., Nadella P., Lewis A., Jensen R., De Hoff C., Dierksheide J. E., VanBuskirk A. M., Magro C. M., Young D. C., Shapiro C. L., and Carson W. E. 3rd. (2004) A phase I study of interleukin 12 with trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-overexpressing malignancies: analysis of sustained interferon γ production in a subset of patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 5027–5037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roda J. M., Parihar R., and Carson W. E. 3rd. (2005) CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides act through TLR9 to enhance the NK cell cytokine response to antibody-coated tumor cells. J. Immunol. 175, 1619–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stephenson R. M., Lim C. M., Matthews M., Dietsch G., Hershberg R., and Ferris R. L. (2013) TLR8 stimulation enhances cetuximab-mediated natural killer cell lysis of head and neck cancer cells and dendritic cell cross-priming of EGFR-specific CD8+ T cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 62, 1347–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]