Abstract

Cofactors of LIM domain proteins, CLIM1 and CLIM2, are widely expressed transcriptional cofactors that are recruited to gene regulatory regions by DNA-binding proteins, including LIM domain transcription factors. In the cornea, epithelium-specific expression of a dominant negative (DN) CLIM under the keratin 14 (K14) promoter causes blistering, wounding, inflammation, epithelial hyperplasia, and neovascularization followed by epithelial thinning and subsequent epidermal-like differentiation of the corneal epithelium. The defects in corneal epithelial differentiation and cell fate determination suggest that CLIM may regulate corneal progenitor cells and the transition to differentiation. Consistent with this notion, the K14-DN-Clim corneal epithelium first exhibits increased proliferation followed by fewer progenitor cells with decreased proliferative potential. In vivo ChIP-sequencing experiments with corneal epithelium show that CLIM binds to and regulates numerous genes involved in cell adhesion and proliferation, including limbally enriched genes. Intriguingly, CLIM associates primarily with non-LIM homeodomain motifs in corneal epithelial cells, including that of estrogen receptor α. Among CLIM targets is the noncoding RNA H19 whose deregulation is associated with Silver-Russell and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndromes. We demonstrate here that H19 negatively regulates corneal epithelial proliferation. In addition to cell cycle regulators, H19 affects the expression of multiple cell adhesion genes. CLIM interacts with estrogen receptor α at the H19 locus, potentially explaining the higher expression of H19 in female than male corneas. Together, our results demonstrate an important role for CLIM in regulating the proliferative potential of corneal epithelial progenitors and identify CLIM downstream target H19 as a regulator of corneal epithelial proliferation and adhesion.

Keywords: cell proliferation, epithelial cell, estrogen receptor, eye, gene regulation, stem cells, coregulators, corneal epithelium, noncoding RNA

Introduction

CLIMs3 are a family (CLIM1/LDB2 and CLIM2/NLI/LDB1) of ubiquitously expressed cofactors (1–3) that form homo- and possibly heterodimers (1, 4) to mediate gene activation. Known to be important for stemness, CLIM2 is required for the maintenance of fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells (5). It is also required for maintenance of epithelial stem cells in the crypts of the small intestine (6), in the bulge of hair follicles (7), and in the basal layer of the mammary gland (8). Intriguingly, CLIM2 has also been shown to regulate the final stages of erythroid differentiation (9). Thus it is likely that this factor acts at multiple stages of differentiation, maintaining progenitor cells in stem cell niches while also promoting cell differentiation at later stages outside of the niche.

Characterized by their N-terminally located dimerization domain and C-terminally located LIM interaction domain, CLIM proteins lack DNA binding capacity and rely on interactions with other transcription factors to regulate gene expression. Through homodimerization, CLIM has the potential to bring together multiple interacting proteins into large multiprotein complexes that coordinate and integrate different input signals to regulate transcription (10). It has also been suggested that the dimerization of CLIM proteins can mediate chromatin looping between promoters and enhancers (11). Although numerous interacting partners of CLIM have been identified in various organs, the DNA-binding proteins that recruit CLIM to gene regulatory regions in corneal epithelial cells remain undefined as does the transcriptional regulatory role of CLIM in this system.

Noncoding RNAs, an integral component of gene regulation during development, confer an additional layer of complexity to transcriptional regulation. H19, one of a few long noncoding RNAs conserved between mouse and human, is a key regulator of proliferation during embryonic development, acting to antagonize the growth-promoting effects of IGF2. Located adjacent to each other, the H19 and Igf2 genes are imprinted: IGF2 is expressed from the paternal allele, and H19 is expressed from the maternal allele (12). Differential methylation of an insulator element between the two genes determines which promoter can make contact with downstream enhancers, highlighting the importance of chromatin structure in gene regulation (12). Both IGF2 and H19 are highly expressed in fetal tissues, and both are down-regulated in most tissues soon after birth (13). Although much work has been done to establish the mechanism whereby imprinting affects gene regulation in this system, many questions remain about the tissue- and temporally specific regulation of this locus during development as well as the tissue-specific functions of this noncoding RNA. In particular, little is known about the expression of H19 and IGF2 in cornea, and nothing is known about the potential role of H19 in corneal epithelial cells. Interestingly, however, H19 is expressed at a higher level in female than male corneas (14).

Clim2 knock-out mice die at embryonic day E9.5 with severe patterning defects (10), whereas Clim1 knock-out mice are phenotypically normal, suggesting redundancy in function between the two genes. To avoid the embryonic lethality and the complex issue of redundancy, we developed a mouse expressing a dominant negative (DN) CLIM under the Krt14 promoter (K14-DN-Clim), targeting DN-CLIM to the basal layer of stratified epithelial tissues, including epidermis, hair follicles, mammary gland, and cornea (7, 15). The K14-DN-Clim mice exhibit decreased numbers of hair follicle stem cells, resulting in hair loss, and have abnormal corneas (7).

Right after birth, the K14-DN-Clim mice develop epithelial hyperplasia and corneal opacity (7). Due to defective cell adhesion, caused at least in part by decreased expression of the hemidesmosome component BP180, stromal edema and blistering frequently occur, resulting in a strong inflammatory reaction and neovascularization. Recurrent wounding and inflammation persist, dramatically perturbing the ability of the corneal epithelium to maintain homeostasis. After this period of hyperplasia, the epithelium of K14-DN-Clim mice undergoes thinning around postnatal days 11 and 16 that persists up to 5 months of age at which point the corneal epithelium begins to develop abnormal characteristics that mimic epidermal differentiation, including cornification in the upper layers of the epithelium; occasional terminal phenotype mice also develop sebaceous- or goblet-like cells in the corneal epithelium.

Although we have shown that cell adhesion defects cause blistering and wounding (7), they alone cannot fully explain the defects in the DN-CLIM cornea, suggesting additional regulatory roles for CLIM. In this study, we investigated the early cellular and molecular mechanisms of action for CLIM in the corneal epithelium. When CLIM complexes are disrupted in the corneal epithelium, there is an initial increase in proliferation followed by a reduction in self-renewal capacity of epithelial progenitor cells. Through gene expression profiling of K14-DN-Clim corneas and in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) experiments, we identify a number of genes known to be involved in epithelial progenitor cell function that are likely directly regulated by CLIM, including regulators of cell proliferation. Among these is the locus of the noncoding RNA H19. We demonstrate a previously undefined role for H19 as a negative regulator of proliferation in corneal progenitor cells and a modulator of genes encoding adhesion molecules. Furthermore, we show that CLIM acting in concert with ERα binds to and activates H19 expression to temper proliferation levels. Thus our study suggests that CLIM-regulated H19 contributes to the balance between proliferation and differentiation in corneal epithelial progenitor cells.

Experimental Procedures

Isolation of RNA from Mouse Cornea and Human Corneal Epithelial Cells for Microarray Gene Expression Analysis

Eye globes were removed from K14-DN-Clim transgenic mice and wild type littermates immediately after sacrifice. Whole corneas were dissected, removing all non-corneal tissues but retaining the peripheral cornea, or limbal region. Total RNA from whole cornea was isolated with TRIzol (Life Technologies) and further purified with the Qiagen RNeasy Micro kit. Corneal RNA sample purity was validated by qPCR expression of tissue-specific markers and the absence of markers for adjacent tissues.

Postnatal day 3 (P3) samples were prepared for microarray with NuGEN Ovation RNA Amplification System V2 and NuGEN FL-Ovation cDNA Biotin Module V2 (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA). Gene expression was assessed with Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays with three mice for each genotype. For human cornea epithelial cells, we used Affymetrix Human 1.0 ST arrays.

Microarray Data Analysis

Array data were quantified with Expression Console version 1.1 software (Affymetrix, Inc.) using the PLIER Algorithm default values. Expression values were then filtered as present/absent at expression 150. Cyber-T web server (16) was utilized to compare wild type and K14-DN-Clim samples and primary human corneal epithelial scrambled control with siH19 for statistically significant differential expression. Gene ontology analysis was performed using DAVID (17, 18).

Culture of Primary Mouse Corneal Epithelial Cells

After sacrifice, mice were sprayed with 70% EtOH, and a drop of Betadine was applied to each eye for 15 s. Eyes were flushed with PBS + penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). Whole eye globes were washed 3 × 10 min in PBS + penicillin/streptomycin. Corneal epithelium was isolated by digestion in Eagle's minimal essential medium + Dispase (20× Dispase, CellNTec) with 50 mm sorbitol and penicillin/streptomycin for 2 h at 37 °C, vortexing the whole eye globes gently every 15 min to aid separation. Corneal epithelial sheets were then peeled off the eye globes. The corneal epithelial sheets were trypsinized for 15 min at 37 °C to obtain a single cell suspension and plated at 100,000 cells/well in a 6-well dish using cells from one eye for each well. A 40-μm strainer was used to exclude cell aggregates. Prior to plating, culture dishes were coated with a 1:15 dilution of PureCol, incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, and rinsed twice with PBS + penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were grown in CnT50 medium (CellNTec). To verify the identity of the cultured primary corneal epithelial cells after 2 weeks in culture, we performed qPCR on a panel of limbal and basal cell markers, corneal differentiation markers, and epidermal differentiation markers (see Fig. 3A). At day 0 of isolation, the isolated epithelial cells had high expression of progenitor cell markers ABCG2 and KRT19 and low expression of corneal epithelial differentiation markers like KRT12. After 2 weeks in culture, the expression of these progenitor markers still remained high compared with differentiation markers. Additionally, loricrin, a marker of epidermal differentiation, was low at all time points (Fig. 3A), indicating these cells were not transitioning to an epidermal cell fate as has been noted in other studies (19) These results suggest that these cells remain progenitor-like after 2 weeks in culture. In some experiments, cell cultures were stained with Ki67 antibody (Abcam ab15580; 1:1000) and Hoechst 3342 (Thermo Scientific; 1 μg/ml). The ratio of positive cells was determined from sequential images across the center of the well, counting a total of 800–1000 Hoechst-positive cells per replicate using ImageJ.

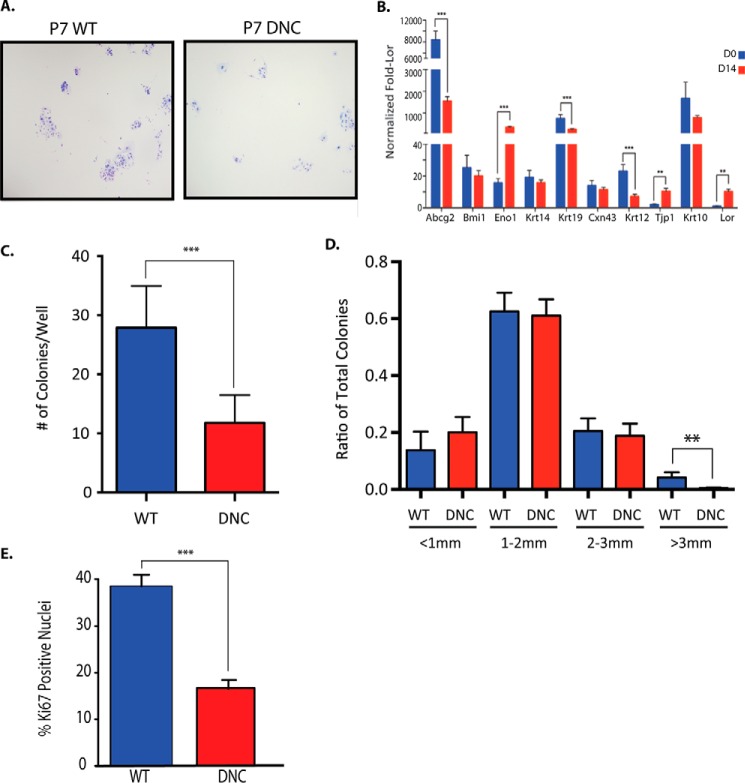

FIGURE 3.

Corneal epithelial progenitor cells are decreased in K14-DN-Clim mice at P7. A, Giemsa stained representative images of colony forming assays from P7 WT and DN-CLIM (DNC) primary corneal epithelial colonies (4×). B, comparison of expression levels across different marker genes at Day 0 (D0) and Day 14 (D14), normalized to loricrin (Lor) expression levels. All data were also normalized to 18S RNA. C, quantification of the number of colonies/well for WT and DN-CLIM corneal epithelial cells (n = 7 WT and 7 DN-CLIM mice). D, the ratio of colonies by size from P7 WT and DN-CLIM cells (n = 7 WT and 7 DN-CLIM mice). E, percentage of ki67-positive nuclei in WT and DN-CLIM corneal epithelial colonies. A t test was used to determine significance: **, p = 0.01; ***, p = 0.001. Error bars represent S.E.

Colony Forming Assays

Primary corneal epithelial cells were isolated as described above and plated at 10,000 cells/well in a 12-well dish. Medium was changed every 3 days. After 2 weeks, cells were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, washed 3 × 5 min with PBS, and stained with Giemsa (Sigma) for 15 min. Wells were then rinsed with distilled H2O, dried, and photographed under a dissection microscope.

BrdU Labeling of K14-DN-Clim Mice

K14-DN-Clim mice and wild type littermates were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg/ml BrdU solution (BD Biosciences; 50 μg/g of body weight) 2 h prior to sacrifice. Whole eye globes were dissected, fixed in neutral buffered formalin at 4 °C overnight followed by processing for paraffin embedding. Eyes were sectioned at 8 μm and stained with rat anti-BrdU (Abcam) and biotinylated anti-rat IgG (Vector Laboratories). Labeling was detected with the Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB)/DAB+ Chromogen Solution (Dako).

Transfections

Primary human corneal epithelial cells were transfected with Lipofectamine LTX with Plus reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Medium was changed after 16 h, and cells were collected 72 h after the addition of transfection reagents. For the siH19 experiments, 100,000 cells in suspension per well (12-well plates) were transfected with 30 nm control (Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus Control pool, D-001810-10-05) or H19 (a pool of Qiagen GeneSolution SI03650598, SI03650605, SI03650612, and SI03650619) siRNAs in triplicate for 72 h before RNA isolation.

MTT Assays

Human corneal epithelial cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. Wells were transfected with the following vectors: empty vector (pcDNA3.1), DN-CLIM (20), and H19 (Dharmacon 3449920). Medium was changed after 16 h. 72 h after transfection, 20 μl of MTT assay reagent (Promega) was added to each well and incubated in the dark for 2 h. Absorbance was read at 490 nm.

ChIP-PCR and ChIP-Seq

ChIP assays were performed as described previously (21, 22) on corneal epithelial cells isolated from P7 mice as described above. The P7 time point was selected as the earliest stage from which sufficient chromatin could be obtained from the corneal epithelial tissue. The following antibodies were used: IgG (Sigma) (for ChIP-PCR only) and anti-Myc tag (Invitrogen); the DN-CLIM construct contains a Myc tag at its N terminus (20). ChIP-qPCR assays were performed with the following antibodies: FOXO1 (Abcam ab39670), RUNX1 (Abcam ab23980), ER (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-543), and CLIM1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc28695). Primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 4. Sequencing libraries were generated for two replicate Myc tag ChIP samples using the Illumina Tru-Seq kit according to the Illumina protocol for ChIP-Seq library preparation with some modification: following previously published protocols (23, 24), after adaptor ligation, 14 cycles of PCR amplification were performed prior to size selection of the library. Clustering and 50-cycle single end sequencing were performed on the Illumina Hi-Seq 2000 Genome Analyzer. Reads were aligned to the mouse mm9 genome using Bowtie (version 0.12.7) with only uniquely aligning reads retained (25). MACS (version 1.4.2) was used to call peaks with an input control sample (26). The 60% of peaks that overlapped between the two replicates were used for all subsequent analyses. MEME and Cistrome were used for motif analysis (27, 28). Galaxy was used to analyze overlaps between ChIP-Seq peaks and genome features (29–31).

Animal Model and Procedures

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of California Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee animal protocol number 2001-2239).

Results

CLIM Regulates Genes Important for Progenitor Cell Maintenance and Tissue Homeostasis

To identify early transcriptional changes that could give insights into the cause of the striking terminal phenotype of the K14-DN-Clim corneas, we characterized the gene expression differences in whole corneas from WT and K14-DN-Clim mice at P3. We identified 1099 differentially expressed genes with a significance of p < 0.05 and a -fold cutoff of 1.5; 361 genes are up-regulated, and 738 genes are down-regulated (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Up-regulated genes are overrepresented in eye development-related gene ontology (GO) categories (17, 18) (Fig. 1A). These include retinal/neural crest factors, such as OPN1SW and RCVRN, which are not normally expressed in the cornea. The enriched GO categories for the down-regulated genes included blood vessel development, cell adhesion, and extracellular matrix organization, linking gene expression changes to the loss of epithelial adhesion, neovascularization, and stromal edema in the K14-DN-Clim corneas. Regulation of proliferation is also a down-regulated category (Fig. 1A). The cell adhesion category of CLIM-regulated genes contains a diverse group of proteins, including numerous laminins, integrins, and claudins. Among the cell proliferation genes down-regulated by K14-DN-Clim in the cornea are cell cycle inhibitors CDKN1A/p21 and CDKN1B/p27 and noncoding RNA H19, a negative regulator of proliferation, consistent with the hyperproliferation observed in the early postnatal period in DN-CLIM corneas (7). We also found enrichment for components of several signaling pathways among the down-regulated genes (Fig. 1B). These include focal adhesion, TGFβ, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and cytokine signaling pathways. In sum, the gene expression changes at P3 are consistent with epithelial hyperplasia, impaired adhesion, and neovascularization observed in the cornea of K14-DN-Clim mice (7).

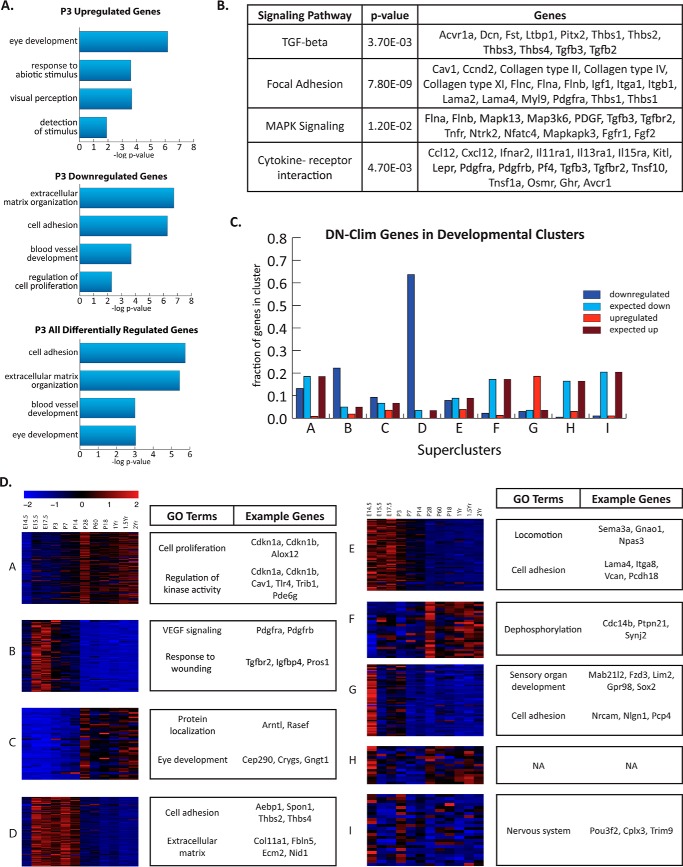

FIGURE 1.

Microarray gene expression analysis of P3 whole corneas reveals genes and pathways with altered expression in K14-DN-Clim mice. A, gene ontology and pathway analysis for differentially expressed genes in P3 DN-CLIM corneas. Separate GO analysis of up-regulated genes and down-regulated genes in P3 DN-CLIM corneas is also shown (n = 3 WT and 3 DN-CLIM mice). B, significant enrichment of signaling pathways among down-regulated genes in P3 DN-CLIM corneas as determined by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. A list of affected genes is shown. C, overlap of genes affected by DN-CLIM with previously defined (32) superclusters of genes (A–I) with similar expression patterns and functional classifications across development and aging of the cornea. The graph shows the fraction of genes in each cluster whose expression is affected by DN-CLIM as well as the fraction expected based on a random overlap. As the number of genes that belong to each supercluster varies, the expected number of overlapping genes is variable. D, heat maps showing previously described normal gene expression patterns of DN-CLIM-affected genes in each developmental cluster. For each cluster, selected GO categories and genes altered in the K14-DN-Clim mice are shown. GEO accession number, GSE59205. NA, not applicable.

CLIM Targets Share Similar Expression Dynamics across Corneal Development

We previously profiled gene expression changes in the cornea over the lifetime of the mouse (from embryonic day E14 through 2 years), identifying genes with similar spatial and temporal expression patterns, allowing the definition of nine superclusters (32). By overlapping these data with genes differentially regulated in K14-DN-Clim mice, we found that several of the previously described developmental time course clusters harbor an overrepresentation of genes affected by DN-CLIM (Fig. 1, C and D). Of the genes up-regulated by DN-CLIM, many belong to Supercluster G, which contains genes involved in eye development and nervous system function. Many K14-DN-Clim down-regulated genes are found in Supercluster B, which is enriched for genes most highly expressed in the stroma, containing many genes with functions in extracellular matrix organization. Response to wounding is among the enriched GO categories for DN-CLIM-affected genes in this cluster; the majority of genes that fall into this category, like TGFBR2, IGFBP4, and PROS1, are stromally enriched and likely represent secondary effects of DN-CLIM expression in the corneal epithelium. Down-regulated genes are also highly enriched in Supercluster D. As in Supercluster B, Supercluster D contains many genes that are involved in the processes of cell adhesion and extracellular matrix organization, including AEBP1, THBS1, and SPON1 (Fig. 1D), correlating well with the observed adhesion defect in the DN-CLIM corneas. Together, these data indicate that CLIM has a broader role in regulating the adhesion of corneal epithelial cells than previously recognized (7).

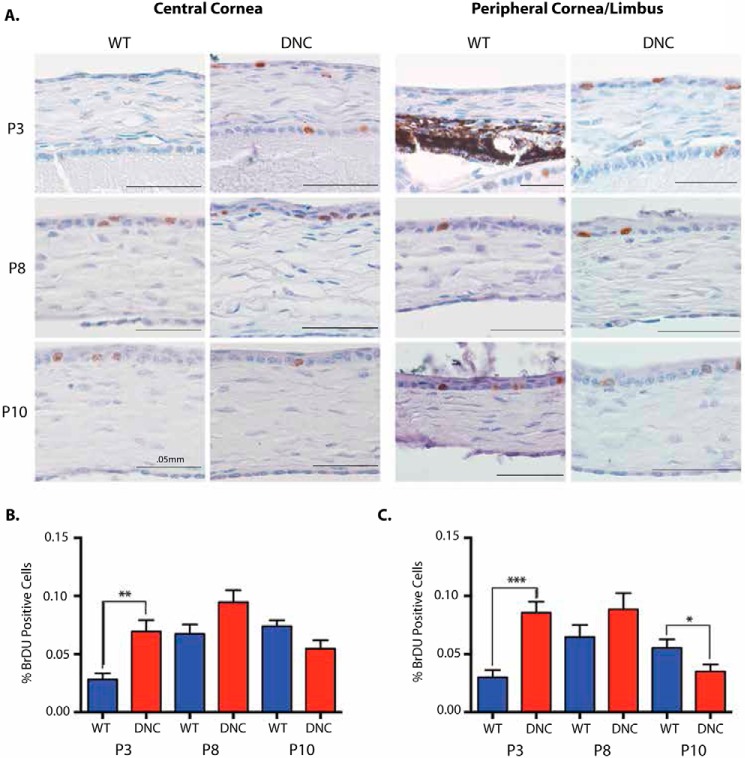

Disrupting CLIM in the Corneal Epithelium Alters Proliferation Dynamics

The enrichment of cell proliferation regulators among the genes affected by K14-DN-Clim in the P3 cornea is consistent with previous observations that the K14-DN-Clim phenotype includes a period of hyperplasia followed by epithelial thinning (7). Therefore, CLIM may play a role in maintaining the progenitor population and in regulating the balance between cell proliferation and differentiation. To study the proliferation dynamics of the developing K14-DN-Clim corneal epithelium, we evaluated BrdU incorporation at P3, P8, and P10 in both the peripheral/limbal (Fig. 2, A and B) and central cornea (Fig. 2, A and C). At P3, the number of proliferating cells was significantly higher in K14-DN-Clim mice in both the central and peripheral cornea. A similar trend was observed at P8, although the difference did not reach statistical significance at this time point. By P10, BrdU labeling decreased in K14-DN-Clim mice with significantly fewer proliferating cells in the peripheral/limbal cornea. Therefore, the corneal epithelium in K14-DN-Clim mice proliferates more actively than wild type cornea in the early days after birth, but as the phenotype progresses, as early as P10, the K14-DN-Clim limbally located corneal epithelial cells are less proliferative.

FIGURE 2.

Corneal epithelial cell proliferation dynamics are altered in K14-DN-Clim mice. A, representative images of BrdU labeling in the cornea at the indicated times (40×). Left panels, central cornea; right panels, peripheral/limbal cornea. B, quantification of the fraction of BrdU-labeled cells in central cornea at the indicated times (n = 3 WT and 3 DN-CLIM (DNC) mice). C, quantification of the fraction of BrdU-labeled cells in peripheral/limbal cornea at the indicated times (n = 3 WT and 3 DN-CLIM mice). A t test was used to determine significance: *, p = 0.05; **, p = 0.01; ***, p = 0.001. Error bars represent S.E.

Disruption of CLIM Leads to Increased Followed by Decreased Proliferative Potential of Corneal Epithelial Progenitor Cells

To test whether the epithelial progenitor cells are perturbed in young K14-DN-Clim mice and whether these effects are intrinsic to the progenitor cells, we adapted a method of culturing primary corneal epithelial cells in colony forming assays (Fig. 3, A and B). After isolation, the epithelial cells have high expression of progenitor cell markers ABCG2 and KRT19 and low expression of corneal epithelial differentiation markers like KRT12, CNX43, and TJP1. After 2 weeks in culture, we detect changes in expression of some of the markers tested, including an increase in differentiation-associated ENO1 and TJP1; however, expression of progenitor markers ABCG2 and KRT19 still remain high compared with differentiation markers. Additionally, loricrin, a marker of epidermal differentiation, is low at all time points (Fig. 3B and supplemental Table 3). These results suggest that the cells remain corneal epithelial progenitor-like after 2 weeks in culture.

Corneal epithelial cells from K14-DN-Clim mice formed significantly fewer colonies than those from wild type littermates (Fig. 3, C and D). In addition, the size of K14-DN-Clim corneal epithelial cell colonies was smaller than controls with the ratio of all K14-DN-Clim colonies skewed toward smaller sized colonies and away from large colonies, which comprised up to 10% of wild type colonies but less than 2% of K14-DN-Clim colonies (Fig. 3D). Additionally, there are fewer ki67-positive cells in the K14-DN-Clim compared with WT colonies (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that already at P7 K14-DN-Clim mice have fewer corneal epithelial progenitor cells with decreased proliferative potential compared with wild type mice. Together, the data also suggest that the initial corneal epithelial hyperplasia followed by thinning in K14-DN-Clim mice starting at P11 is due to altered intrinsic proliferative potential of corneal epithelial progenitors.

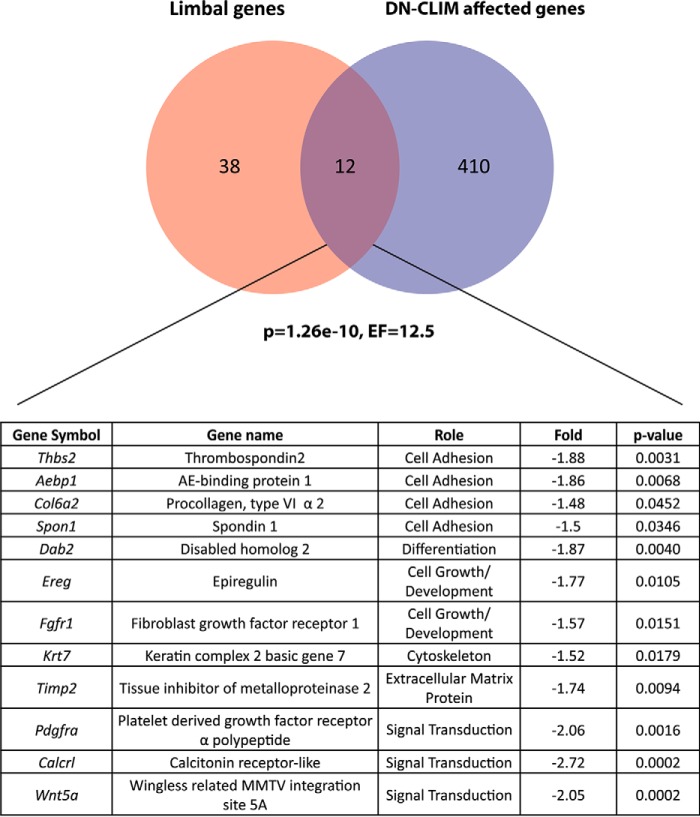

Limbally enriched Genes Are Regulated by CLIM

Considering the effect of CLIM on corneal epithelial progenitors, we next sought to gain insights into the effect of DN-CLIM on the expression of genes characteristic for limbal epithelial cells. We took advantage of previously published data comparing gene expression in central corneal and limbal cell populations captured by laser microdissection in the mouse (33) (Fig. 4). There is a statistically significant overlap of genes differentially regulated by DN-CLIM at P3 and the limbal epithelially enriched genes determined by the aforementioned study (33). Interestingly, all of the limbal epithelially enriched genes that are affected by DN-CLIM in the mouse cornea are down-regulated, further supporting a role for CLIM as transcriptional activators of a gene program regulating corneal progenitor cells (Fig. 4). Among these are genes involved in cell growth, cell adhesion, and extracellular matrix deposition (Fig. 4). These categories are highly similar to the GO categories found in the overall analysis for genes affected by DN-CLIM in the cornea. Several of the down-regulated limbally enriched genes that are in the K14-DN-Clim cornea, including THBS2, a cell adhesion gene, and WNT5A, an inhibitor of the canonical Wnt pathway in some systems, are also significantly down-regulated in the aging cornea (32), further supporting a causal link between CLIM and the regenerative potential of the cornea.

FIGURE 4.

Previously defined limbally enriched genes (33) significantly overlap with differentially regulated genes in P3 K14-DN-Clim corneas. The overlapping genes and their roles are listed with the -fold decrease in DN-CLIM corneas as well as p value for the differential regulation. The hypergeometric distribution was used to determine significance. EF, enrichment factor; AE, adipocyte enhancer; MMTV, murine mammary tumor virus.

ChIP-Seq Identifies Direct Targets of CLIMs

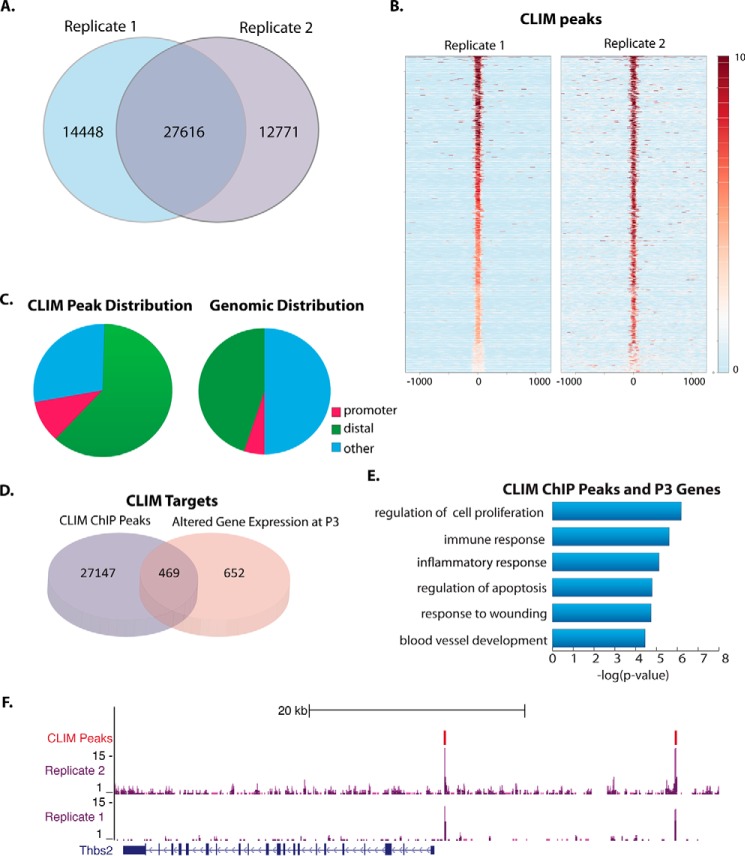

To identify which of the genes whose expression is affected by K14-DN-Clim are direct targets of CLIMs, we performed ChIP-Seq on corneal epithelium isolated from P7 mouse corneas using an antibody to the Myc tag of DN-CLIM. The P7 time point was selected as the earliest age from which sufficient chromatin could be obtained from corneal epithelium for ChIP-Seq. ChIP experiments were performed in duplicate; at a 5% false discovery rate cutoff, ∼60% (27,616) of the peaks overlapped between the two replicates (Fig. 5, A and B). To minimize false positives in our analyses, these 27,616 overlapping peaks were used for all further analyses.

FIGURE 5.

ChIP-Seq identifies direct targets of CLIMs in corneal epithelium. A, overlap of ChIP-Seq peaks from each Myc tag ChIP replicate. B, plot of density of ChIP-Seq reads from each replicate centered on CLIM peaks from replicate 2. The scale shows the intensity of ChIP-Seq reads within the selected regions. C, distribution of ChIP-Seq peaks across genomic features: promoter, 0–2-kb window upstream of TSS; distal, 50 kb upstream of TSS through 5 kb downstream of TSS. D, overlap of ChIP-Seq peaks and genes affected by DN-CLIM in P3 corneas. E, GO analysis of genes affected by DN-CLIM at P3 that have a CLIM peak within 40 kb. F, CLIM peaks in the upstream region of thrombospondin 2 (Thbs2). GEO accession number, GSE49409.

Whereas 10% of CLIM peaks were found in proximal promoter regions, the great majority were found in distal regions, defined as 50 kb upstream through 5 kb downstream of a TSS, excluding proximal promoters (0–2 kb upstream of TSS); these distal binding sites are candidate locations for regulatory regions like enhancers (Fig. 5C). This genomic distribution of CLIM peaks deviates strongly from the background genomic distribution, consistent with previous ChIP-Seq studies for CLIM in erythroid cells (9) and for the CLIM-interacting factor LIM homeodomain (LHX) 2 in hair follicle stem cells (34).

CLIM Target Genes Are Involved in Both Stem Cell Maintenance and Epithelial Differentiation

We next overlapped the CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks in corneal epithelium with genes whose transcripts were affected by DN-CLIM in P3 corneas. Four hundred sixty-nine genes, representing ∼40% of differentially regulated transcripts, also had a nearby CLIM ChIP-Seq peak (Fig. 5D). These genes were enriched for a subset of GO categories from the analysis of all genes bound by CLIM, including cell proliferation, blood vessel development, eye development, and cytoskeletal development (Fig. 5E), categories that are explanatory for the phenotype of the DN-CLIM cornea. Among the cell proliferation genes is H19, which encodes a noncoding RNA. Many proteins involved in extracellular matrix interaction and focal adhesion signaling are also directly bound by CLIM, including thrombospondins, integrins, collagens, and filamin. Furthermore, several of the limbally enriched genes that are affected by DN-CLIM at P3 (Fig. 4) also have CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks in the corneal epithelium at P7; these include Wnt5a, Fgfr1, and Thbs2 (Fig. 5F). Together, these data indicate that CLIM directly controls a number of different genes involved in regulation of corneal epithelial progenitor cell function.

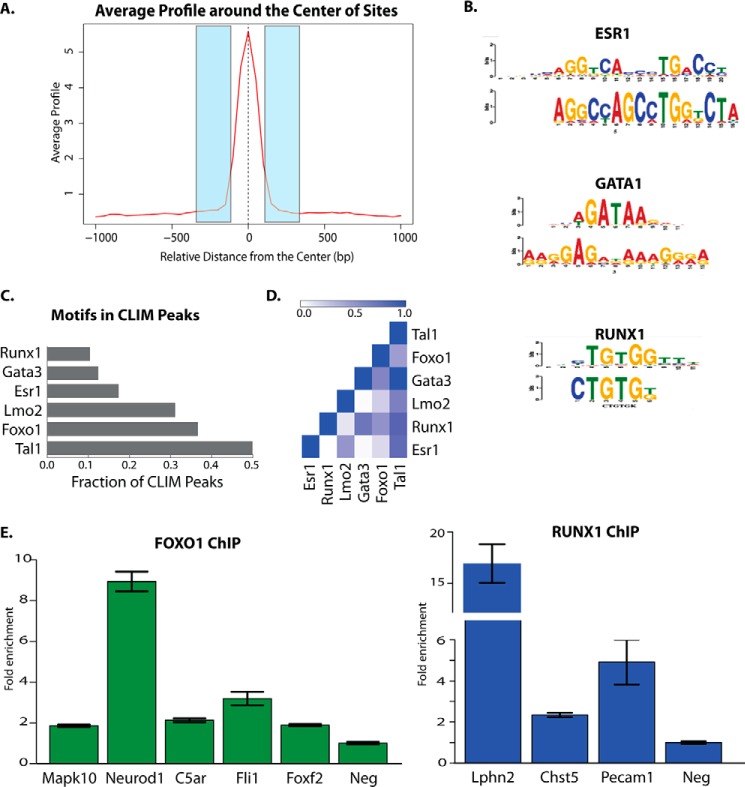

CLIM Binding Sites Are Enriched for Selective Transcription Factor Motifs

Next we sought to identify the transcription factors recruiting CLIM to target genes in the corneal epithelium. Interrogating the 250 bases of flanking DNA from each side of the center summits of the ChIP-seq peaks (Fig. 6A) with the non-biased motif search algorithm MEME, we found overrepresented DNA-binding motifs that were highly similar to the GATA, RUNX1, and ERα (ESR1) motifs (Fig. 6B). Directed motif searches on the CLIM binding regions revealed an enrichment of motifs for additional factors known to interact with CLIM in other systems, including GATA factors, TAL1, LMO2, GFI1, and FOXO1 (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, LHX motifs were not enriched in CLIM binding regions. To determine whether CLIM might associate with multiple DNA-binding proteins, we looked for co-occurrence of motifs within the ChIP-Seq peaks (Fig. 6D). Nearly all GATA3 motifs had nearby TAL1 motifs, indicating that these two factors bind together. Additionally, we found an increase in the co-occurrence of GATA3 and RUNX1 motifs as well as an increase in the number of ESR1 and LMO2 motifs found together in peaks, indicating that biases exist in the grouping of CLIM-associated transcription factors at different locations. These findings also suggest that CLIM primarily associates with non-LHX DNA-binding proteins in the corneal epithelium. To confirm the co-occupancy of the DNA-binding proteins whose motifs are enriched within CLIM peaks, we performed ChIP-qPCR experiments with mouse corneal epithelium using antibodies to RUNX1 and FOXO1. Both factors bind to a subset of their predicted motifs within the tested CLIM peaks (Fig. 6E), indicating that these factors bind with CLIM in vivo in developing corneal epithelium.

FIGURE 6.

ChIP-Seq identifies CLIM-associated DNA-binding proteins in corneal epithelium. A, schematic of regions flanking CLIM peaks used for motif analysis. B, enriched motifs found by MEME in regions flanking peaks. C, enriched motifs found in flanking 250 bp of ChIP-Seq peaks by directed motif searches. D, co-occurrence of motifs found in CLIM peaks. E, ChIP-qPCR for FOXO1 and RUNX1 binding to their predicted DNA-binding motifs within selected CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks. Error bars represent S.E. Neg, negative control region.

CLIM Targets H19 to Regulate Corneal Epithelial Proliferation Dynamics

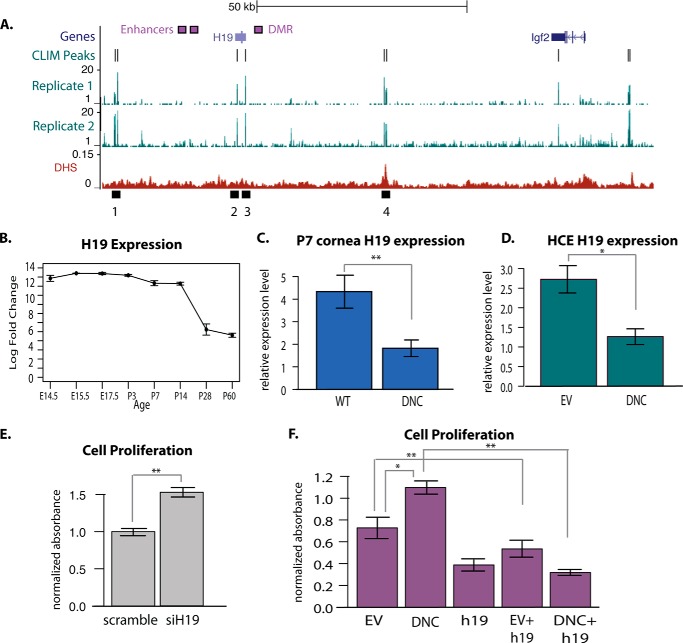

One of the genes bound by CLIM with expression changes in the DN-CLIM cornea encodes the noncoding RNA H19 (Fig. 7A), a factor with well defined roles in regulation of proliferation and growth in other systems. During development, H19 counteracts the growth-promoting role of adjacent factor IGF2, thereby reducing proliferation in progenitor cells (12). We did not find evidence that CLIM binds to the differentially methylated region involved in imprinting of the locus or to the two enhancers that regulate H19 and Igf2 based on the imprinting methylation at the differentially methylated region. However, DN-CLIM binds to two sites overlapping the H19 gene body (Fig. 7A) and to additional upstream and downstream sites, many of which overlap previously defined H19 enhancers and DNase-hypersensitive regions (35, 36). Similar to other tissues, the expression of H19 is highest in the cornea during embryogenesis and decreases strongly after completion of development between P14 and P28 (Fig. 7B). We validated by qPCR that cornea H19 expression levels are also decreased in DN-CLIM mice compared with WT littermate controls at P7 as they are at P3 (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, H19 is also down-regulated in primary human corneal epithelial cells in the presence of DN-CLIM (Fig. 7D), indicating that CLIM regulates H19 in a cell-autonomous manner.

FIGURE 7.

DN-CLIM regulates noncoding RNA H19. A, view of DN-CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks and wig files at the H19/Igf2 locus. The lowest panel shows DNase hypersensitivity at the H19/Igf2 locus (DHS) in G1E cells. Black boxes 1–4 represent CLIM binding regions selected for further analyses. B, expression of H19 across mouse cornea development and aging. C, expression of H19 in WT and DN-CLIM (DNC) corneas at P7 (n = 4 WT and 6 DNC). D, expression of H19 in empty vector (EV)- and DN-CLIM (DNC)-transfected human corneal epithelial cells (n = 6 empty vector and 4 DN-CLIM). E, MTT cell proliferation assays for cells transfected with scrambled control or siH19 (n = 6 per condition). F, MTT cell proliferation assays for cells transfected with the indicated constructs (n = 6 per condition). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.E.

We next performed a series of knockdown studies to determine whether H19 affects human corneal epithelial cell proliferation and whether the effects of DN-CLIM on corneal epithelial cell proliferation could be mediated through its regulation of H19. Knockdown of H19 by siRNA caused an increase in proliferation (Fig. 7E), suggesting that H19 is a repressor of corneal epithelial progenitor cell proliferation. Conversely, expression of H19 in corneal epithelial cells leads to decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 7F), further supporting a proliferation-suppressive role of H19 in corneal epithelial cells. Cells transfected with DN-CLIM alone showed an increase in proliferation (Fig. 7F), consistent with the reduction in H19 gene expression (Fig. 7D). However, in the presence of H19, DN-CLIM could not increase proliferation, supporting the idea that DN-CLIM, at least in part, affects proliferation through regulation of H19 (Fig. 7F). Together, these data indicate that CLIM, acting in a cell-autonomous manner, regulates corneal epithelial cell proliferation via H19.

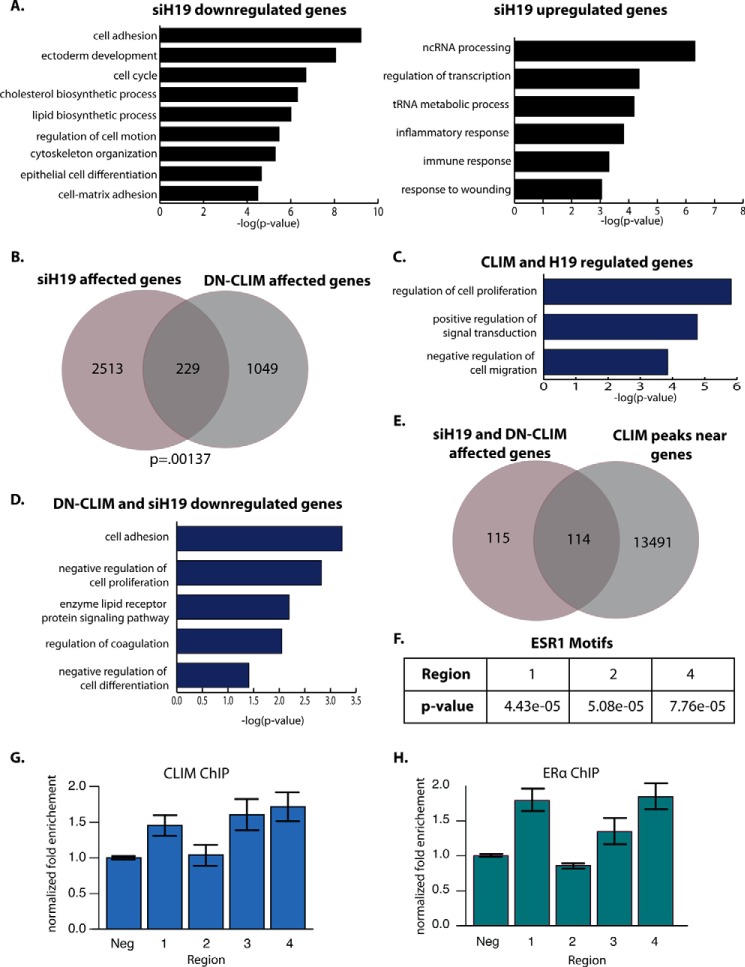

H19 Has a Broad Gene-regulatory Role in Corneal Epithelial Cells

Next we wanted to understand the gene-regulatory role of H19 in corneal epithelial cells and to explore whether CLIM activation of H19 might account for non-cell proliferation effects of CLIM. We used siRNA to knock down H19 in primary human corneal epithelial cells. Microarray gene expression analysis revealed that 1336 genes are down-regulated 1.5-fold or more by siH19 compared with scrambled control and that 1406 genes are up-regulated at least 1.5-fold at a p value cutoff of 0.01 (supplemental Table 5). Down-regulated genes are enriched in GO categories related to cell adhesion, epithelial development, cell cycle, and lipid metabolism (Fig. 8A). Up-regulated genes are enriched in noncoding RNA processing and transcriptional regulation categories (Fig. 8A). These data indicate that the direct or indirect gene-regulatory role of H19 in corneal epithelial cells is much broader than an effect on cell cycle regulators. In particular, H19 appears to up-regulate a number of genes encoding cell adhesion molecules.

FIGURE 8.

H19 and DN-CLIM regulate a shared set of genes in human corneal epithelial cells. A, GO analysis for genes down-regulated 1.5-fold or more in siH19 compared with scrambled control and for genes up-regulated 1.5-fold or more in siH19 compared with scrambled control (p < 0.01, n = 3). B, overlap of siH19-affected genes in primary human cornea epithelial cells and DN-CLIM-affected genes in P3 mouse cornea. C, GO analysis for genes affected by both siH19 and DN-CLIM. D, GO analysis for genes down-regulated by both siH19 and DN-CLIM. E, overlap of genes affected by both siH19 and DN-CLIM with genes that have a nearby CLIM peak. F, estrogen receptor motifs in DN-CLIM-bound regions at the H19 gene locus. G, ChIP-qPCR with CLIM1/2 at the indicated regions of the H19 locus (see Fig. 7A). H, ChIP-qPCR with ERα at the indicated regions of the H19 locus. GEO accession number, GSE80387. Error bars represent S.E. ncRNA, noncoding RNA; Neg, negative control region.

In comparing genes affected by siH19 with those affected by DN-CLIM, we found a small but significant overlap of 229 genes that are affected both by DN-CLIM and H19 (Fig. 8B). As expected, these shared targets are most strongly enriched for GO categories related to cell proliferation. They are also enriched for signal transduction and cell migration categories (Fig. 8C). Interestingly, genes that are down-regulated by both H19 and DN-CLIM are most highly enriched in categories related to cell adhesion and cell proliferation (Fig. 8D), suggesting that the additional adhesion defects observed in the K14-DN-Clim mouse cornea may also be caused by reduced H19. Approximately half of the genes affected by DN-CLIM and siH19 are also bound by CLIM (Fig. 8E), indicating that, in part, CLIM and H19 target the same genes.

CLIM and ERα Co-occupy the H19 Locus

H19 has been shown to be more highly expressed in the female cornea than in male cornea (14). Because the estrogen receptor motif was enriched within the CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks, we looked for high scoring ER motifs in the CLIM-bound regions at the H19 locus. CLIM-bound regions 1, 2, and 4 near H19 (Figs. 7A and 8F) contain strong ER motifs, suggesting that estrogen signaling may regulate H19 expression and that CLIM may bind with ER to regulate H19 expression. ChIP experiments in P7 mouse corneal epithelium verified that both CLIM and ER bind to regions 1 and 4 of the H19 locus and that CLIM also binds region 3 (Figs. 7A and 8, G and H). Previously published data on ER binding across numerous human breast cancer cell lines reveal that ER localizes to many sites within the H19/Igf2 locus, including a site immediately upstream of H19 and a site overlapping enhancer signals between H19 and Igf2 (37); the homologous regions for both of these are bound by CLIM and ER in mouse cornea epithelium, suggesting that ERα may regulate H19 more broadly across tissues. Together, these results identify a role for H19 in modulating corneal epithelial proliferation and indicate that CLIMs bind with ER to regulate H19.

Discussion

In this study, we provide genomic and functional evidence that CLIM, acting in an epithelium-intrinsic manner, regulates the proliferation dynamics of corneal epithelial progenitor cells. Using combined gene expression analyses and ChIP-Seq approaches, we identified direct genomic targets of CLIMs, including H19, a noncoding RNA that acts to suppress corneal epithelial progenitor cell proliferation. We show that, in addition to modulating the expression of cell proliferation regulators, H19 directly or indirectly affects the expression of multiple cell adhesion genes in corneal epithelial cells. Furthermore, we also identify a previously uncharacterized role for the estrogen receptor in the corneal epithelium both as a cofactor of CLIMs in corneal epithelium and as a potential upstream regulator of H19.

CLIMs Regulate Cell Proliferation and Repopulation Dynamics in the Corneal Epithelium

The DN-CLIM corneas exhibit a striking misregulation of genes involved in cell proliferation, an aspect crucial for progenitor maintenance and tissue homeostasis. Together, the BrdU incorporation data and colony forming assays suggest that the corneal epithelial progenitor cell population is altered in K14-DN-Clim mice with an initial increase in proliferation followed by a decrease by P10. The DN-CLIM corneal epithelial cells also have less repopulating potential compared with WT. This initial increase in proliferation, characterized by a reduction in cell cycle inhibitor expression, may cause the stem cell compartment to exhaust its potential early, resulting in later reductions in proliferation and repopulating capacity. A number of cell cycle inhibitors, including Cdkn1b and H19, are bound directly by CLIM and misregulated in K14-DN-Clim corneas, suggesting that they are direct targets of CLIM. Based on the large number of potential direct CLIM targets within the Wnt signaling pathway, CLIM likely further influences the cell cycle through its regulation of Wnt signaling.

CLIM Interacts with Distinct Cohorts of Transcription Factor Binding Sites to Regulate Gene Expression in the Cornea

Identifying genome-wide CLIM binding sites in the cornea through ChIP-Seq experiments provided insights into the mechanisms of CLIM function in cornea, including information on potential binding partners recruiting CLIM to chromatin. Thus we found that several DNA-binding motifs were enriched in CLIM binding regions, including motifs for TAL1, GATA, RUNX1, and others; all are factors known to interact with CLIM in other systems (2, 38, 39). Our validation of FOXO1 and RUNX1 binding to a subset of their motifs within CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks indicates that these interactions occur in the corneal epithelium. Not all motifs for these two factors were found to be occupied in our ChIP-PCR experiments. However, these sites could be bound at other developmental time points or could be bound by other FOXO or RUNX family members, as we only tested for FOXO1 and RUNX1 binding.

Intriguingly, among the enriched motifs flanking CLIM peaks was the motif for ERα (ESR1). CLIM has previously been shown to be a cofactor for ERα in mammary epithelia but not in stratified epithelia; in mammary epithelial cells, CLIM functions to enhance ERα-mediated gene expression (40). Estrogen receptors are expressed in all ocular surface tissues, including the cornea. This is interesting as a recent study highlighted the sex-specific differences in corneal wound healing (41).

CLIM was originally identified through its interaction with LHX proteins (1–3). Therefore, it is interesting to note that the motif for LHX was not enriched within the flanking regions of CLIM ChIP-Seq peaks. This is in contrast to hair follicle stem cells where CLIM seems to function through interactions with LHX2 (7, 42). The low expression of LHX proteins in the cornea (32), combined with the lack of enriched LHX motifs adjacent to CLIM chromatin binding sites, suggests that in the corneal epithelium CLIM primarily interacts with other factors to effect its regulation of gene targets and that the exact composition of the CLIM-mediated multiprotein complexes varies with tissue type. LIM domain only (LMO) proteins, strongly expressed in the corneal epithelium, may play a role in recruiting CLIM to non-LHX complexes (32).

The biases we discovered in co-occurrence rates for motifs of different CLIM-interacting partners indicate that CLIM can act through different protein complexes in the same cell type to regulate gene expression. We found that TAL1 motifs are strongly enriched near all other CLIM cofactors tested. Additionally, the GATA and RUNX motifs are commonly found together as are the ESR and LMO2 motifs. An interaction between LMO4 and ERα has been described previously in mammary epithelium (43) and striatum (44); our unbiased ChIP-Seq approach provides evidence of this interaction between LMO factors and ERα in corneal epithelium as well. These data suggest that CLIM plays a role in bringing together different transcription factors to function synergistically at specific regulatory locations. It is tempting to speculate that that these preferences for specific combinations of CLIM co-binding transcription factors may be a mechanism of regulation that is also active in other CLIM-expressing tissues.

CLIM Regulates Noncoding RNA H19

We identified the noncoding RNA H19 as a CLIM target in corneal epithelium, adding to the mechanistic complexity of CLIM-mediated transcriptional regulation and defining for the first time a role for H19 as a regulator of proliferation in the corneal epithelium. Our findings also point to a broader role for H19 in corneal epithelial development as we show that H19 affects the expression of genes involved in a wide range of functions, including cell adhesion, lipid metabolism, noncoding RNA processing, and immune response. The overlap of genes regulated by H19 and CLIM suggests that CLIM influences gene expression at a subset of its downstream targets through regulation of H19; interestingly, these targets include not only cell proliferation genes but also genes involved in cell adhesion as well as other functional categories. The idea that CLIM acts on H19 to mediate regulation of downstream targets is further supported by the finding that approximately half of the genes regulated by both CLIM and H19 do not have a nearby CLIM ChIP-Seq peak; it is likely that CLIM regulates these targets through binding and activation of H19.

Located adjacent to each other along the chromosome, H19 and Igf2 have opposing roles in regulating proliferation. Expression is determined by imprinted methylation at a region between H19 and Igf2, termed the differentially methylated region, that directs shared downstream enhancer elements to the proper promoter (Igf2 on the paternal allele and H19 on the maternal allele) (45). Neither differentially methylated region nor the two downstream enhancers are bound by CLIMs, but additional regions further downstream of H19 that have been shown to be enhancers specifically for H19 are bound by CLIM as is an upstream enhancer (46). Because the selectivity of the enhancers in the region is key to proper expression of the locus, the structure and chromatin looping formed between enhancer and promoter are crucially important. Due in part to its ability to homodimerize, CLIM has been shown to play a major role in forming and maintaining chromatin loops at the β-globin locus during hematopoiesis (11). Thus it is plausible that CLIM functions at the H19/Igf2 locus to regulate chromatin structure and interactions between enhancers and promoters.

Two developmental syndromes are linked to misregulation of the H19/Igf2 locus. Silver-Russell syndrome causes growth defects and is associated with loss of paternal IGF2 expression. Ophthalmologic abnormalities, including refractive errors, have been linked to this syndrome, suggesting that proper regulation of the Igf2/H19 locus is important for the development of ocular structures (47). The converse syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann, associated with hypermethylation of the locus, causes excessive growth and predisposes patients toward tumor development (48). Additionally, sex-specific expression of H19 and IGF2 has been documented; both are significantly more highly expressed in the iris, retina, ciliary bodies, eyecup, and cornea of the female mouse eye compared with the male (14). This is intriguing as our studies show that DN-CLIM binding at H19 overlaps ER motifs, and we find that CLIMs and ERα bind to the same regions within the H19 locus. CLIM and ERα have been shown to interact directly in mammary epithelium (40); our study is the first to suggest that CLIMs may interact with the estrogen receptor outside of reproductive tissues and that CLIMs may act together with ERα to up-regulate expression of H19.

CLIMs Act through Unique Mechanisms to Modulate Progenitor Cells in Different Tissues

CLIMs play a number of roles in progenitor cell maintenance: they promote quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells (49), maintain hair follicle stem cells in the epidermis through interaction with LHX2 (7, 34, 42, 50), and maintain the proliferative potential of basal stem cells, acting upstream of Fgfr2 in mammary epithelium (15). In our studies characterizing CLIM regulation of corneal epithelial progenitor cell maintenance, we did not find evidence for CLIM binding to the proximal Fgfr2 promoter, and motif analysis suggests that CLIM acts independently of LHX factors in the cornea. Additionally, H19 is not misregulated by DN-CLIM in mammary epithelial nor hair follicle stem cells. These results therefore indicate that, although CLIMs have a broad role in regulating progenitor cell dynamics in many tissues, they do so through unique mechanisms in different tissues.

Author Contributions

D. N. S., R. H. K., and B. A. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. D. N. S., R. H. K., M. L. S., H. H., J. K. C., W. W., and Z. Y. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the University of California Irvine Genomics High-Throughput Facility for work on the whole genome expression arrays and sequencing.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01EY019413 and R01AR44882 (to B. A.), T15LM00744 (to R. H. K. and M. L. S.), F32AR065356 (to H. H.), and T32GM08620 (to J. K. C.) and by California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Grant TG2-01152 (to D. S. and M. L. S.). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession numbers GSE59205, GSE49409, and GSE80387.

This article contains supplemental Tables 1–5.

- CLIM

- cofactor of LIM domain proteins

- DN

- dominant negative

- K14

- keratin 14

- Seq

- sequencing

- LHX

- LIM homeodomain

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- P

- postnatal day

- GO

- gene ontology

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- TSS

- transcription start site

- ESR

- estrogen receptor.

References

- 1. Jurata L. W., Kenny D. A., and Gill G. N. (1996) Nuclear LIM interactor, a rhombotin and LIM homeodomain interacting protein, is expressed early in neuronal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11693–11698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agulnick A. D., Taira M., Breen J. J., Tanaka T., Dawid I. B., and Westphal H. (1996) Interactions of the LIM-domain-binding factor Ldb1 with LIM homeodomain proteins. Nature 384, 270–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bach I., Carrière C., Ostendorff H. P., Andersen B., and Rosenfeld M. G. (1997) A family of LIM domain-associated cofactors confer transcriptional synergism between LIM and Otx homeodomain proteins. Genes Dev. 11, 1370–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Storbeck C. J., Wagner S., O'Reilly P., McKay M., Parks R. J., Westphal H., and Sabourin L. A. (2009) The Ldb1 and Ldb2 transcriptional cofactors interact with the Ste20-like kinase SLK and regulate cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4174–4182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li L., Jothi R., Cui K., Lee J. Y., Cohen T., Gorivodsky M., Tzchori I., Zhao Y., Hayes S. M., Bresnick E. H., Zhao K., Westphal H., and Love P. E. (2011) Nuclear adaptor Ldb1 regulates a transcriptional program essential for the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 129–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dey-Guha I., Mukhopadhyay M., Phillips M., and Westphal H. (2009) Role of ldb1 in adult intestinal homeostasis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 5, 686–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu X., Mannik J., Kudryavtseva E., Lin K. K., Flanagan L. A., Spencer J., Soto A., Wang N., Lu Z., Yu Z., Monuki E. S., and Andersen B. (2007) Co-factors of LIM domains (Clims/Ldb/Nli) regulate corneal homeostasis and maintenance of hair follicle stem cells. Dev. Biol. 312, 484–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salmans M. L., Yu Z., Watanabe K., Cam E., Sun P., Smyth P., Dai X., and Andersen B. (2014) The co-factor of LIM domains (CLIM/LDB/NLI) maintains basal mammary epithelial stem cells and promotes breast tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soler E., Andrieu-Soler C., de Boer E., Bryne J. C., Thongjuea S., Stadhouders R., Palstra R. J., Stevens M., Kockx C., van Ijcken W., Hou J., Steinhoff C., Rijkers E., Lenhard B., and Grosveld F. (2010) The genome-wide dynamics of the binding of Ldb1 complexes during erythroid differentiation. Genes Dev. 24, 277–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mukhopadhyay M., Teufel A., Yamashita T., Agulnick A. D., Chen L., Downs K. M., Schindler A., Grinberg A., Huang S. P., Dorward D., and Westphal H. (2003) Functional ablation of the mouse Ldb1 gene results in severe patterning defects during gastrulation. Development 130, 495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng W., Lee J., Wang H., Miller J., Reik A., Gregory P. D., Dean A., and Blobel G. A. (2012) Controlling long-range genomic interactions at a native locus by targeted tethering of a looping factor. Cell 149, 1233–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaffer C. R., Grinberg A., and Pfeifer K. (2001) Regulatory mechanisms at the mouse Igf2/H19 locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8189–8196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gabory A., Jammes H., and Dandolo L. (2010) The H19 locus: role of an imprinted non-coding RNA in growth and development. BioEssays 32, 473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reinius B., and Kanduri C. (2013) Elevated expression of H19 and Igf2 in the female mouse eye. PLoS One 8, e56611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salmans M. L., Yu Z., Watanabe K., Cam E., Sun P., Smyth P., Dai X., and Andersen B. (2014) The Co-Factor of LIM domains (CLIM/LDB/NLI) maintains basal mammary epithelial stem cells and promotes breast tumorigenesis. PLoS Genetics 10, e1004520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kayala M. A., and Baldi P. (2012) Cyber-T web server: differential analysis of high-throughput data. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W553–W559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sherman B. T., Huang da W., Tan Q., Guo Y., Bour S., Liu D., Stephens R., Baseler M. W., Lane H. C., and Lempicki R. A. (2007) DAVID Knowledgebase: a gene-centered database integrating heterogeneous gene annotation resources to facilitate high-throughput gene functional analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 8, 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang da W., Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawakita T., Espana E. M., He H., Yeh L. K., Liu C. Y., and Tseng S. C. (2004) Calcium-induced abnormal epidermal-like differentiation in cultures of mouse corneal-limbal epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 3507–3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bach I., Rodriguez-Esteban C., Carrière C., Bhushan A., Krones A., Rose D. W., Glass C. K., Andersen B., Izpisúa Belmonte J. C., and Rosenfeld M. G. (1999) RLIM inhibits functional activity of LIM homeodomain transcription factors via recruitment of the histone deacetylase complex. Nat. Genet. 22, 394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu Z., Mannik J., Soto A., Lin K. K., and Andersen B. (2009) The epidermal differentiation-associated Grainyhead gene Get1/Grhl3 also regulates urothelial differentiation. EMBO J. 28, 1890–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hopkin A. S., Gordon W., Klein R. H., Espitia F., Daily K., Zeller M., Baldi P., and Andersen B. (2012) GRHL3/GET1 and trithorax group members collaborate to activate the epidermal progenitor differentiation program. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmidt D., Wilson M. D., Spyrou C., Brown G. D., Hadfield J., and Odom D. T. (2009) ChIP-seq: using high-throughput sequencing to discover protein-DNA interactions. Methods 48, 240–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gordon W. M., Zeller M. D., Klein R. H., Swindell W. R., Ho H., Espetia F., Gudjonsson J. E., Baldi P. F., and Andersen B. (2014) A GRHL3-regulated repair pathway suppresses immune-mediated epidermal hyperplasia. J. Clin. Investig. 124, 5205–5218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., and Salzberg S. L. (2009) Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C. A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D. S., Bernstein B. E., Nusbaum C., Myers R. M., Brown M., Li W., and Liu X. S. (2008) Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bailey T. L., Boden M., Buske F. A., Frith M., Grant C. E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W. W., and Noble W. S. (2009) MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu T., Ortiz J. A., Taing L., Meyer C. A., Lee B., Zhang Y., Shin H., Wong S. S., Ma J., Lei Y., Pape U. J., Poidinger M., Chen Y., Yeung K., Brown M., Turpaz Y., and Liu X. S. (2011) Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol. 12, R83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blankenberg D., Von Kuster G., Coraor N., Ananda G., Lazarus R., Mangan M., Nekrutenko A., and Taylor J. (2010) Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 19, Unit 19.10.1–19.10.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giardine B., Riemer C., Hardison R. C., Burhans R., Elnitski L., Shah P., Zhang Y., Blankenberg D., Albert I., Taylor J., Miller W., Kent W. J., and Nekrutenko A. (2005) Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 15, 1451–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goecks J., Nekrutenko A., Taylor J., and Galaxy Team (2010) Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 11, R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stephens D. N., Klein R. H., Salmans M. L., Gordon W., Ho H., and Andersen B. (2013) The Ets transcription factor EHF as a regulator of cornea epithelial cell identity. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 34304–34324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou M., Li X. M., and Lavker R. M. (2006) Transcriptional profiling of enriched populations of stem cells versus transient amplifying cells. A comparison of limbal and corneal epithelial basal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19600–19609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Folgueras A. R., Guo X., Pasolli H. A., Stokes N., Polak L., Zheng D., and Fuchs E. (2013) Architectural niche organization by LHX2 is linked to hair follicle stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell 13, 314–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosenbloom K. R., Sloan C. A., Malladi V. S., Dreszer T. R., Learned K., Kirkup V. M., Wong M. C., Maddren M., Fang R., Heitner S. G., Lee B. T., Barber G. P., Harte R. A., Diekhans M., Long J. C., Wilder S. P., Zweig A. S., Karolchik D., Kuhn R. M., Haussler D., and Kent W. J. (2013) ENCODE data in the UCSC Genome Browser: year 5 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D56–D63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kent W. J., Sugnet C. W., Furey T. S., Roskin K. M., Pringle T. H., Zahler A. M., and Haussler D. (2002) The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12, 996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ross-Innes C. S., Stark R., Teschendorff A. E., Holmes K. A., Ali H. R., Dunning M. J., Brown G. D., Gojis O., Ellis I. O., Green A. R., Ali S., Chin S. F., Palmieri C., Caldas C., and Carroll J. S. (2012) Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature 481, 389–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meier N., Krpic S., Rodriguez P., Strouboulis J., Monti M., Krijgsveld J., Gering M., Patient R., Hostert A., and Grosveld F. (2006) Novel binding partners of Ldb1 are required for haematopoietic development. Development 133, 4913–4923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Visvader J. E., Mao X., Fujiwara Y., Hahm K., and Orkin S. H. (1997) The LIM-domain binding protein Ldb1 and its partner LMO2 act as negative regulators of erythroid differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13707–13712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnsen S. A., Güngör C., Prenzel T., Riethdorf S., Riethdorf L., Taniguchi-Ishigaki N., Rau T., Tursun B., Furlow J. D., Sauter G., Scheffner M., Pantel K., Gannon F., and Bach I. (2009) Regulation of estrogen-dependent transcription by the LIM cofactors CLIM and RLIM in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 69, 128–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang S. B., Hu K. M., Seamon K. J., Mani V., Chen Y., and Gronert K. (2012) Estrogen negatively regulates epithelial wound healing and protective lipid mediator circuits in the cornea. FASEB J. 26, 1506–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rhee H., Polak L., and Fuchs E. (2006) Lhx2 maintains stem cell character in hair follicles. Science 312, 1946–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh R. R., Barnes C. J., Talukder A. H., Fuqua S. A., and Kumar R. (2005) Negative regulation of estrogen receptor α transactivation functions by LIM domain only 4 protein. Cancer Res. 65, 10594–10601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lasek A. W., Gesch J., Giorgetti F., Kharazia V., and Heberlein U. (2011) Alk is a transcriptional target of LMO4 and ERα that promotes cocaine sensitization and reward. J. Neurosci. 31, 14134–14141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Singh P., Lee D.-H., and Szabó P. E. (2012) More than insulator: multiple roles of CTCF at the H19-Igf2 imprinted domain. Front. Genet. 3, 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Drewell R. A., Arney K. L., Arima T., Barton S. C., Brenton J. D., and Surani M. A. (2002) Novel conserved elements upstream of the H19 gene are transcribed and act as mesodermal enhancers. Development 129, 1205–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Andersson Grönlund M., Dahlgren J., Aring E., Kraemer M., and Hellström A. (2011) Ophthalmological findings in children and adolescents with Silver-Russell syndrome. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95, 637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Azzi S., Abi Habib W., and Netchine I. (2014) Beckwith-Wiedemann and Russell-Silver Syndromes: from new molecular insights to the comprehension of imprinting regulation. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 21, 30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Povinelli B. J., and Nemeth M. J. (2014) Wnt5a regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and repopulation through the Ryk receptor. Stem Cells 32, 105–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mardaryev A. N., Meier N., Poterlowicz K., Sharov A. A., Sharova T. Y., Ahmed M. I., Rapisarda V., Lewis C., Fessing M. Y., Ruenger T. M., Bhawan J., Werner S., Paus R., and Botchkarev V. A. (2011) Lhx2 differentially regulates Sox9, Tcf4 and Lgr5 in hair follicle stem cells to promote epidermal regeneration after injury. Development 138, 4843–4852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.