Abstract

Insights concerning leukemic pathophysiology have been acquired in various animal models and further efforts to understand the mechanisms underlying leukemic treatment resistance and disease relapse promise to improve therapeutic strategies. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a vertebrate organism with a conserved hematopoietic program and unique experimental strengths suiting it for the investigation of human leukemia. Recent technological advances in zebrafish research including efficient transgenesis, precise genome editing, and straightforward transplantation techniques have led to the generation of a number of leukemia models. The transparency of the zebrafish when coupled with improved lineage-tracing and imaging techniques has revealed exquisite details of leukemic initiation, progression, and regression. With these advantages, the zebrafish represents a unique experimental system for leukemic research and additionally, advances in zebrafish-based high-throughput drug screening promise to hasten the discovery of novel leukemia therapeutics. To date, investigators have accumulated knowledge of the genetic underpinnings critical to leukemic transformation and treatment resistance and without doubt, zebrafish are rapidly expanding our understanding of disease mechanisms and helping to shape therapeutic strategies for improved outcomes in leukemic patients.

Keywords: Zebrafish, T-ALL, B-ALL, AML, CLL, CML, Xenograft, Leukemia, Transplantation

Introduction

Leukemias are hematopoietic malignancies commonly subdivided into four major types—acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)—and other less common types, such as hairy cell leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia [1]. The incidence (number of new cases per year) of leukemias differs from their prevalence (total cases of disease). AML has the highest incidence, but CLL is the most prevalent. Although leukemia occurs more frequently in older adults, ALL is the most common form of cancer in children and adolescents. Leukemogenic processes are generally induced by multiple genetic changes including chromosomal translocations, mutations, and deletions [2, 3].

The Genetic Basis of Human Leukemia

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is characterized by constitutively activated NOTCH1 signaling accompanied by deletions of the tumor suppressor genes p16/INK4A and p14/ARF in more than 70% of cases (Table 1). This NOTCH1 activation is the result of mutations in the NOTCH1 gene, involving the extracellular heterodimerization and/or the C-terminal PEST domains [13], and about 15% of cases are associated with FBXW7 mutations that reduce the degradation of activated NOTCH1 [14, 15]. Additionally, aberrant expression of certain transcription factor genes, such as TAL1/SCL, TAL2, LYL1, BHLHB1, MYC, LMO1, and LMO2, contributes to T-ALL pathogenesis (Table 1) [4]. These transcription factors normally remain quiescent during T cell development, but become aberrantly activated during T-ALL pathogenesis. Their aberrant expression results from either recurrent chromosomal translocations or, in some cases, mutations affecting upstream regulatory pathways that can inactivate transcriptional repressor networks or induce aberrant transcriptional activation. B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) is characterized by aneuploidy or gross chromosomal rearrangements in approximately 75% of cases (Table 1). Chromosomal rearrangements affecting genes related to hematopoiesis, tumor suppression, and tyrosine kinase activity are common and in combination with further genetic aberrations such as aberrant oncogene activation, lead to the leukemic phenotype [16].

Table 1.

Summary of genetic alterations in human ALL, AML, CLL, and CML

| Disease | Gene activation, fusion, inactivation or mutations |

Translocations | Deletions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALL |

RB1, WT1, GATA3, CCND2, ETV6, RUNX1, EZH2, SUZ12, EED, PHF6, NOTCH1, FBXW7, PTEN, NRAS, NF1, JAK1, JAK3, FLT3, IL7R, CDKN2A/2B, BCL11B, LEF1, MYC, CDKN1B, NUP214-ABL1, TEL-AML1, EML1-ABL1, ETV6-ABL1, ETV6-JAK2, BCR-ABL1 |

t(14;21)(q11.2;q22) t(11;14)(p13;q11) t(1;14)(p32;q11) t(1;7)(p32;q34) t(7;7)(p15;q34) t(10;11)(p13;q14) t(11;19)(q23;p13) t(7;14)(q34;q13) t(14;20)(q11;p11) t(6;7)(q23;q34) t(7;19)(q34;p13) t(7;11)(q34;p15) t(7;12)(q34;p12) t(11;14)(p15;q11) t(7;9)(q34;q32) t(7;11)(q34;p13) inv(7)(p15q34) inv(14)(q11.2q13) inv(14)(q13q32.33) |

del(1p32) del(11p13) del(9q34) del(9p21) |

| AML |

IDH2, NRAS, TP53, KRAS, RUNX1, NPM1, FLT3, DNMT3A, IDH1, TET2, CEBPA, WT1, PTPN11, KIT, MYST3-NCOA2, AML1-ETO, NUP98-HOXA9 |

t(15;17) t(8;21)(q22;q22) inv(16)(11q23) inv(8)(p11q13) |

del(5q) del(7q) |

| CLL |

ZMYM3, CHD2, SF3B1, U2AF2, SFRS1, XPO1, ATM, TP53, LRP1B, MAPK1, MYD88, IGHV, NOTCH1, FBXW7, DDX3X, TLR2, POT1 |

t(14;18)(q32;q21) t(14;19)(q32;q13) t(11;14)(q13;q32) t(17;18)(p11;q11) |

del(11q22-23) del(17p13) del(13q14) |

| CML |

BCR-ABL1, EVI1, RB1, TP53, CDKN2A, ETV6-JAK2 |

t(9;22)(q34;q11) inv(3)(q21q26) t(3;21)(q26;q22) t(15;17) (q22;q12-21) |

IKZF1 Δ3–6 |

AML is a genetically complex disease that has historically been sub-classified based on both large-scale cytogenetic and individual gene abnormalities [17]. Importantly, knowledge about the mutational status of genes for FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA, and KIT is helping to refine treatment protocols; whereas other mutations—including DNMT3A, IDH1/2, and TET2—are poised to improve prognostic prediction (Table 1) [18]. Though the biological functions of many AML-related genes have been detailed [17], it remains an ongoing effort to assign driver vs. passenger mutations (i.e., to distinguish pathogenic driver mutations from coincident alterations). Such assignments will allow better definition of clinically relevant patient populations.

CLL is a leukemia subtype with high genetic heterogeneity, where the prevalence of any given mutation totals only 10–15% of cases (Table 1). However, associated gene mutations affect distinct pathways including those of NOTCH signaling, mRNA splicing, processing, and transport, and the DNA damage response (Table 1) [8]. Despite the quantity of genetic mutations in CLL, their roles in disease initiation and progression remain elusive. For instance, Quesada et al. defined 78 recurrently mutated CLL genes, with particular focus on the splicing factor SF3B1 [19]. As in T-ALL, NOTCH1 mutations are found in CLL cases, but it remains unclear whether these mutations drive leukemogenesis. Larger sample sizes may facilitate the detection of putative driver mutations affecting smaller patient subsets (2–5% of cases) [20]. The genetic heterogeneity in CLL has led to the investigation of numerous candidate genes and a handful of commonly affected pathways.

Unlike CLL, greater than 90% of CML cases are associated with a unifying genetic abnormality known as the Philadelphia chromosome—a specific chromosomal translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 9 & 22: t(9;22)(q34;q11) (Table 1) [21]. This translocation causes the expression and constitutive action of the oncogenic tyrosine kinase BCR-ABL1 [22]. The most common BCR-ABL1 fusion protein—p210BCR-ABL—results from translocation within the break point cluster region (BCR) between exons 12 and 16 on chromosome 22 (Table 1). This fusion protein activates a number of downstream signaling pathways, including: (a) RAS-MAPK signaling that transcriptionally upregulates BCL-2; (b) AKT signaling that stabilizes MYC and thus increases transcriptional activation of MYC downstream targets; and (c) STAT5 signaling that leads to the transcription of BCL-xL [23]. Although targeting the BCR-ABL1 fusion protein with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., Imatinib) is an effective therapeutic strategy for the management of CML during the chronic phase, the disease remains incurable upon progression [24].

Remaining Challenges in Leukemia Treatment

Intensification of standard therapeutic agents has improved the clinical outcome in many leukemia subtypes. However, 5-year survival rates for leukemia remain low: 68.8% for ALL, 24.9% for AML, 83.1% for CLL, and 58.6% for CML [1]. Among adult patients, only 20–30% with ALL and 30–35% (younger than 60 years) with AML achieve complete remission and are considered cured [2, 3]. These high mortalities are resulted from induction failure, disease progression and relapse, and toxicities associated with current treatment regimens [25]. For example, following disease relapse, patients with acute leukemia face an extremely poor 5-year survival rate (~10%) where treatment intensification often increases toxicity without improving outcome [26]. Direct and indirect toxicological complications include anthracycline-related cardiotoxicities, hepatotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy, central neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, cutaneous toxicity, myelosuppression—leading to anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and infection—capillary leak syndrome, cytokine release syndrome, hypogammaglobulinemia, graft-versus-host disease, and veno-occlusive disease [26–30]. The need for more tolerable and targeted therapies is clear.

The development of monoclonal antibodies, immunotherapies, cancer vaccines, and improvements in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are contributing to the more effective management and treatment of human leukemia. Antibody therapies are generally more tolerable than traditional chemotherapeutics and remain an area of developmental focus despite limited monotherapeutic efficacy [31]. Very recently, the bi-specific T-cell engager monoclonal antibody blinatumomab received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Other antibody therapeutics in clinical trial includes traditional naked antibodies, immunoconjugates, and immunotoxins [26]. As compared to traditional small molecule drugs, these next-generation antibody therapeutics are characterized by improved malignant-cell-specific cytotoxicity [31].

Immune-based strategies for leukemia treatment represent an area of growing research. Cancer vaccines and immunotherapies are currently in clinical trial and provide potential means of reducing relapse following chemotherapy and HSCT [25, 32]. Small clinical trials for ALL and CLL have demonstrated that patients’ own T cells can be genetically engineered (e.g. chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells) to potently eradicate cancer cells by targeting tumor antigens [32–34]. Additionally, drugs modifying cancer-related immunosuppression or enhancing innate immunity are likely to improve the efficacy and durability of next-generation leukemia treatments [1].

These advances, both as monotherapies and potentially as combination therapies with current standard protocols, promise to significantly advance the treatment of leukemia. To fully exploit this potential, research to identify and develop biomarkers that can predict drug efficacies in individual patients is necessary [35]. Predictive biomarkers will be valuable for assessing immunotherapies, particularly as applied to cancer vaccinations, where discordant patterns of antibody responses arise from even identical treatment regimens [36]. Unsurprisingly, even targeted therapies are not completely effective and are complicated by therapeutic resistance, characterized by the expansion of cancer clones lacking expression of the target gene [26]. Therefore, in vivo research using animal models of human leukemia will allow us to better understand mechanisms of treatment resistance, advanced disease, and treatment toxicities, along with immunopathologies.

Conservation of Zebrafish Hematopoietic Program

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a freshwater fish with unique characteristics, including high fecundity, rapid development, transparency, and closer homology to humans than invertebrates. Zebrafish hematopoiesis is highly conserved, making it well suited to study both normal hematopoiesis and malignant transformation [37–39]. As in mammals, the cellular components of zebrafish blood are produced and replenished by distinct yet overlapping waves of primitive and definitive hematopoiesis [37, 40, 41]. Beginning 12 hours post-fertilization (hpf), primitive erythropoiesis occurs in the intermediate cell mass and myelopoiesis initiates in the anterior lateral mesoderm. Definitive hematopoiesis begins around 26 hpf when hemogenic endothelial cells give rise to hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta—a structure within the aorta-gonad-mesonephros [42, 43]. These HSCs then migrate to secondary hematopoietic compartments: the caudal hematopoietic tissue (an intermediate site of hematopoiesis comparable to the liver of mammals), the thymus (an organ where T lymphocytes mature), and the kidney marrow (equivalent to mammalian bone marrow). HSCs in the kidney subsequently give rise to all hematopoietic lineages (erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid) throughout the life of the fish (Fig. 1).

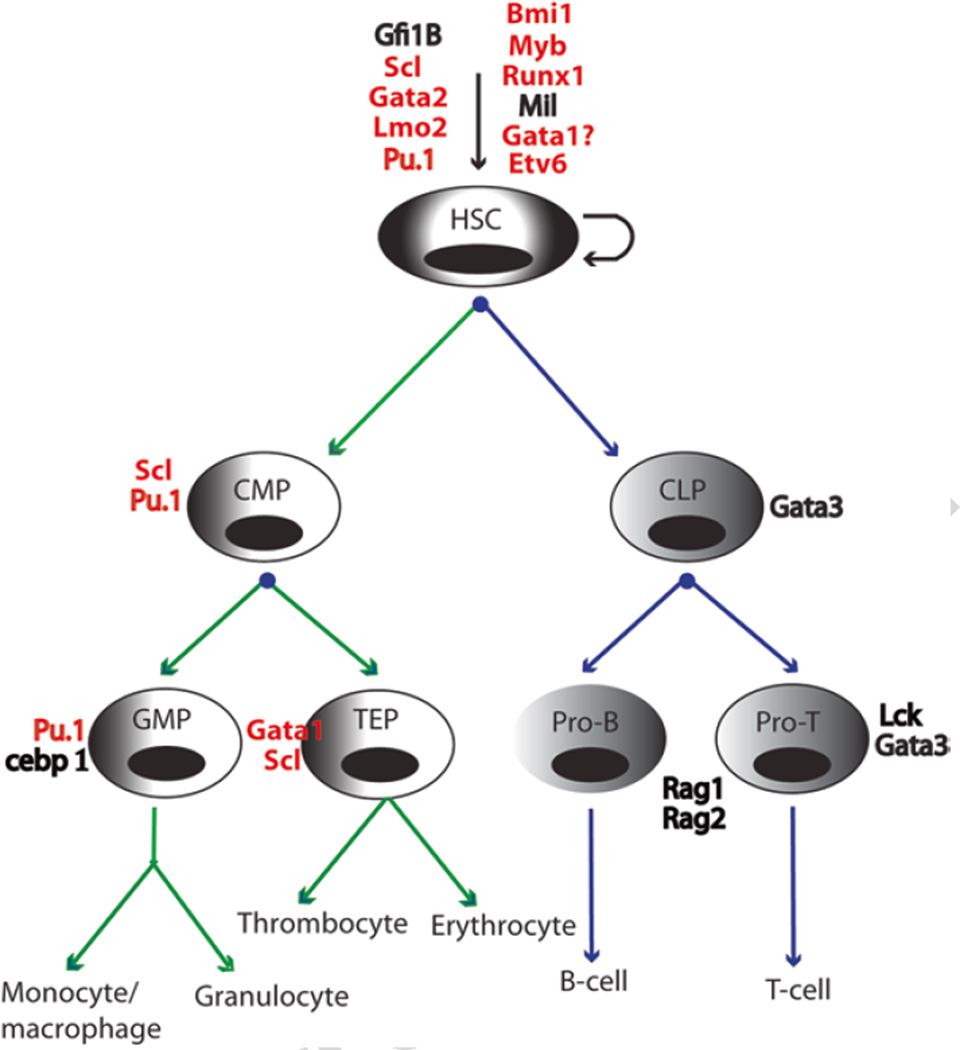

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of zebrafish definitive hematopoiesis. Green arrow lines indicate the myeloid lineage and blue arrow lines indicate the lymphoid lineage. Transcription factors implicated in hematopoiesis are shown next to each cell type and those associated with mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, or misexpression in leukemia are shown in red. HSC hematopoietic stem cells, CMP common myeloid progenitor, CLP common lymphoid progenitor, GMP granulo/cyte/macrophage progenitors, TEP thrombocyte and erythroid progenitor, Pro-B pro-B-lymphocytes, Pro-T pro-T-lymphocytes

Since 1963, and especially during the past two decades [44], significant knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying blood cell development has been acquired through investigations of gene inactivation and/or heritable mutations in zebrafish [45, 46]. Indeed, the genetic programs governing zebrafish blood cell development are highly conserved. Critical transcription factors such as Gata2, Scl (Tal1), Lmo2, Myb, and Runx1 control the self-renewal and differentiation of HSCs in zebrafish and mammals alike (Fig. 1) [46, 47]. Similarly, progenitor cell development is finely tuned by the expression of a number of specific transcription factors and regulators. For instance, the expression of pu.1 (spi1) and cebp 1 control the fate of granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMP) (Fig. 1) [48–50]. The transient expression of Rag1 and Rag2 recombinases promotes the maturation of T and B lymphocytes (Fig. 1) [51]. To ensure proper blood cell development, the expression of these genes must be tightly regulated and their aberrant expression often leads to differentiation arrest and malignant transformation.

Following the elucidation of these blood cell regulators, their promoter regions were isolated and characterized, thereby allowing the generation of transgenic zebrafish lines expressing fluorescent reporter genes and oncogenes implicated in hematopoietic malignancy. The use of multiple transgenic fluorescent reporter systems (e.g. green fluorescent protein [GFP], enhanced GFP [EGFP], and red fluorescent protein [RFP]) has facilitated the visualization and study of specific cell lineages and the monitoring of leukemic initiation and progression in live zebrafish [41, 45]. To date, transgenic lines of all three hematopoietic lineages have been generated: (a) gata1:dsRed2 for erythrocytes [52]; (b) pu.1:GFP for myeloid progenitor cells [50], mpo:GFP for neutrophils [53], lyzC:dsRed2 and mpeg:GFP for macrophages [54]; and (c) lck:EGFP for the T cell lineage exclusively [55], and rag1:GFP and rag2:GFP for both B and T cells [56, 57]. Additionally, the availability of CD41:GFP transgenic fish has facilitated the isolation of HSCs on the basis of GFP intensity, where low GFP intensity identifies HSCs and medium or high intensity identifies thrombocytes [58, 59]. In summary, investigations utilizing these transgenic and mutant fish have provided important insight into normal hematopoiesis and malignant transformation (detailed in the section “Leukemia Modeling and Mechanistic Insights”).

Technological Advances Enabling the Experimental Tractability of Zebrafish

In the last decade, researchers have developed and optimized multiple methodologies for the zebrafish, making this system particularly amenable to experimental manipulations. Improvements in transgenic techniques have enabled the misexpression of various oncogenes in blood lineages, while ongoing mutagenesis efforts within the zebrafish community have generated a large collection of mutants, facilitating forward genetic screens and identification of mutations modifying leukemic phenotypes. Moreover, the ability to precisely edit the zebrafish genome has facilitated the study of tumor suppressor inactivation in relation to leukemogenesis. Finally, the transparency and optical clarity of zebrafish embryos and the adult Casper strain—so called for its ghost-like appearance [60]—allow the tracking of leukemic cell behavior at single-cell resolution, in real time, without surgical intervention.

Transgenesis and Mutagenesis

The application of meganuclease I-SceI- or Tol2-mediated transgenesis has been shown to significantly improve rates of germ-line integration as compared to conventional transgenesis with linear-DNA injection (16–50% vs. 1–5%) [61, 62]. The ability to efficiently generate transgenic zebrafish in the injected (F0) generation represents a major advantage over other animal models, where the generation of stable transgenic animals typically requires two to three generations before these new lines can be used experimentally. The development of conditional transgenesis (e.g. Cre/lox-regulated, tamoxifen-regulated, GAL4-UAS-regulated, and tetracycline-inducible systems) has provided further capacity to enable the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressors with spatial and temporal specificity [63–66]. Moreover, the ability to deliver two to three transgenic constructs into the same cell through co-injection is particularly useful. Co-injection facilitates the identification of transgenic fish by the activity of a fluorescent reporter construct alongside the transgene of interest, enabling the selection of fish with positive transgene expression [67]. Additionally, the co-expression of multiple transgenes of interest in the same cells enables the dissection of multiple genetic pathways in the leukemic context [67, 68]. These improvements in transgenic techniques have led to the generation of various zebrafish leukemia models and the functional study of candidate leukemogenic genes (detailed in the section “Leukemia Modeling and Mechanistic Insights”).

While zebrafish transgenesis enables the misexpression of exogenous genes in a specific cell lineage, mutagenesis can effect enhanced expression, dominant-negative effects, and/or the inactivation of an endogenous gene throughout the entire organism. With UV irradiation, chemicals (e.g. N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea [ENU]), viruses, and transposons (e.g. Tol2) as mutagens, high-throughput mutagenesis projects have generated large collections of zebrafish mutants, including blood mutants, over the past two decades [69, 70]. These mutant fish represent a rich resource for investigators working to identify mutations capable of modifying leukemic onset and progression. A recent genetic suppressor screen utilizing a collection of insertional mutants led to the identification of dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase as an important contributor to Myc-induced T-ALL pathogenesis (Anderson and Feng, 2015, personal communications). Targeting Induced Local Lesions in Genomes (TILLING) combines the use of a chemical mutagen (e.g. ENU) with a single-base-mutation screening technique. With advances in whole-genome sequencing, TILLING-by-sequencing (Illumina) has been developed to rapidly identify single-nucleotide changes and thus significantly speed the screening process. This technique has led to the identification of multiple mutants affecting blood development, including the rag1R797stop and pu.1G242D mutants (Fig. 1) [71, 72]. The rag1R797stop mutant is defective in V(D)J recombination and fails to generate mature T and B cells [72]. The pu.1G242D mutant results in reduced Pu.1 activity and increased granulocytes with patterns comparable to human AML [71].

Gene Inactivation and Genome Editing

Gene inactivation is the preferred method for the functional study of tumor suppressors in the leukemic context. Although antisense morpholino oligonucleotides have been used for gene knockdown in zebrafish, they are susceptible to undesirable off-target effects and their transience is unsuited to studies in larval or adult fish [73]. Small hairpin RNA gene inactivation is effective in embryos [74]; however, its feasibility in adult fish remains to be proven. The zebrafish community has successfully adapted multiple genome editing techniques, including zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) technologies, enabling site-directed mutagenesis and precise single-base genome editing [75–77]. The Langenau group successfully applied TALENs to generate rag2E450fs mutants with reduced numbers of mature T and B cells [78, 79]. Both rag1R797stop and rag2E450fs mutant fish are immunocompromised and provide excellent tools for the long-term engraftment of various tissues and leukemic cells [72, 78]. With efficiencies comparable to ZFNs and TALENs, the CRISPR/Cas9 system provides an adaptable, simple, and rapid method to generate loss-of-function alleles by targeting open reading frames [76]. Because leukemia is a heterogeneous disease, often involving the simultaneous misexpression of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressors, the ability to genetically manipulate the zebrafish genome easily and precisely makes zebrafish particularly well suited for modeling human leukemia.

Improved Imaging Techniques

Given the optical clarity of embryos and the transparency of adult Casper fish, the zebrafish is an excellent model for tracking the movement of normal or malignant blood cells with live-cell imaging [80]. Fluorochrome labeling of each blood cell lineage enables researchers to monitor leukemic initiation, dissemination, and regression with a fluorescent microscope in real time. The most commonly used fluorochrome is GFP, though blue fluorescent protein (e.g., lyn-Cyan), zs Yellow, mCherry, and dsRed2 are available as well. To track fluorescent tumor cells, researchers fuse GFP or EGFP to an oncoprotein of choice; examples include EGFP-mMYC [81], EGFP-TEL-AML1 [82], EGFP-ICN1 [83], and MYST3/NCOA2-EGFP [84]. However, this strategy is limited by the fact that, in some cases, fast degradation of the oncogene can weaken the GFP signal. Additionally, the fluorochrome tag may adversely affect oncogene functionality and/or subcellular localization [80]. To avoid these pitfalls, co-injection is used to independently drive the expression of both the oncogene and the fluorescent protein with separate transgenic constructs within the same cells [67, 68].

Stereomicroscopy is broadly applied for the imaging and dissection of fluorescently labeled tissues in zebrafish. However, stereomicroscopes are limited to imaging fish individually. Moreover, it is difficult to acquire an image of the entire adult fish, even at low magnification. To facilitate high-throughput screening and scoring of zebrafish, the Langenau group developed a light emitting diode (LED) fluorescent macroscope system [85, 86]. This LED fluorescent macroscope is cost effective and capable of simultaneously imaging up to 30 fish within a petri dish. Additionally, LED macroscopy can differentiate five different fluorochromes and is suited to the real-time imaging and time-lapse video recording of live fish. A drawback of LED macroscopy is its reduced sensitivity, limiting detailed imaging of small tumors and single circulating cells.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) is a powerful technology with increased optical resolution and contrast. Laser light is focused on a single point within a defined focal plane, eliminating noise from other planes and reducing image distortions. Fluorescent scanning of multiple focal planes can be reconstructed as a z-series overlay and mapped in three dimensions onto a zebrafish anatomical atlas. Sabaawy et al. used LSCM to image EGFP-TEL1-RUNX1 expression in adult fish [82]. Zhang et al. demonstrated the ability to track and count circulating blood cells in adult zebrafish via the combination of LSCM and in vivo flow cytometry [87]. Disadvantages of LSCM scanning include its rate of acquisition (each pixel is acquired individually) and high levels of laser exposure, often causing tissue photobleaching and phototoxicity. By contrast, spinning disc confocal microscopy (SDCM) utilizes a disc with different pinhole apertures, allowing the acquisition of multiple pixels simultaneously, thereby decreasing laser exposure. Although the resolution of SDCM is not as good as that of LSCM, its imaging is significantly faster, thereby limiting photobleaching and phototoxicity.

Significant progress has been made in improving the tractability of zebrafish for the modeling and mechanistic elucidation of leukemogenesis. With the increasing sophistication and expansion of genetic techniques and imaging modalities, the zebrafish has proven its experimental utility in disease research alongside both murine models and cell culture systems.

Leukemia Modeling and Mechanistic Insights

As previously described, zebrafish have unique advantages that make them especially suited to the investigation of hematopoietic malignancies. To date, investigators have generated zebrafish models of T-ALL, B-ALL, and AML that can be experimentally manipulated to elucidate both the molecular and genetic components of leukemic transformation, progression, and maintenance.

Disease Modeling

T-ALL

Multiple zebrafish T-ALL models have been generated during the past 12 years. The first model was developed via transgenesis in the Look laboratory. In this T-ALL model, the murine c-Myc gene (mMyc) was fused to EGFP to drive the expression of the EGFP-mMyc fusion protein under the lymphocyte-specific rag2 promoter (Tables 1 and 2) [81]. This model provides the capacity to monitor the dissemination of tumor cells in a live vertebrate organism under a fluorescent microscope. However, high mortality rates among these heavily diseased leukemic fish preclude their fecundity. To overcome this, Langenau et al. developed a Cre/lox-regulated conditional system in which EGFP-mMyc expression is controlled by Cre-mediated recombination of the loxP-dsRed2-loxP cassette upon Cre mRNA injection (Table 2) [64]. This technique allows the maintenance of tumor-free rag2:loxP-dsRed2-loxP-EGFP-mMyc transgenic fish in the absence of Cre expression.

Table 2.

Summary of zebrafish models of leukemia

| Tumor | Method | Transgenes or genes disrupted | Earliest disease onset |

Characteristics/application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-ALL | Stable transgenesis | rag2:EGFP-mMyc | 22 days | The first zebrafish transgenic model of cancer | [81] |

| T-ALL | Cre/lox-regulated |

rag2:loxP-dsRed2-loxP-EGFP- mMyc Cre mRNA injection |

4 months | Similar to human T-ALL subtype with SCL and LMO2/LMO1 activation |

[64] |

| T-ALL | Cre/lox-regulated |

rag2:loxP-dsRed2-loxP-EGFP- mMyc;hsp70:Cre |

2 months | Heat-shock inducible; Elucidation of genetic basis of T-LBL dissemination to T-ALL; Determined the effect of p53 inactivation on Myc-induced T-ALL onset |

[88–90] |

| T-ALL | Tamoxifen-regulated | rag2:MYC-ER;mitfa | 4 weeks | Mechanistic dissection of MYC-PTEN-AKT- BIM regulation; Small molecule screens to identify perphenazine with anti-leukemic activity |

[63, 90, 91] |

| T-ALL | Stable transgenesis | rag2:EGFP-ICN1 | 5 months | Demonstrated the effect of bcl-2 to accelerate ICN1-induced T-ALL onset |

[83] |

| T-ALL | Transient transgenesis | rag2:Myr-Akt2 | 6 weeks | Determined the role of Akt2 in T-ALL maintenance and progression |

[63, 89] |

| T-ALL | Random ENU-mediated mutagenesis |

srk hlk otg |

3–6 months | Discovery of potential new genetic players for T-ALL |

[92] |

| B-ALL | Stable transgenesis |

β-actin:EGFP-TEL-AML1 ef1:EGFP-TEL-AML1 |

8 months | The first B-ALL model in zebrafish; Provided a tool for enhancer screens |

[82] |

| AML | Stable transgenesis | pu.1:MYST3-NCOA2-EGFP | 14 months | Demonstrated the oncogenic potential of the MYST3-NCOA2 fusion protein in vivo |

[84] |

| MPN | Cre/lox-regulated |

β-actin:loxP-dsRed2-loxP- KRASG12D; hsp70-Cre |

3–6 months | The first zebrafish MPN model; Studied the role of MAP/ERK pathway in MPN |

[93] |

| MPN | Stable transgenesis | hsp70:AML1-ETO | 1-dpf embryos | Expanded myelopoiesis in embryos with gene expression resembling human AML; Small molecule screens to identify the Cox1 inhibitor |

[94, 95] |

| MPN | Cre/lox-regulated |

pu.1:loxP-EGFP-loxP-NUP98- HOXA9; hsp70-Cre |

19–23 months | Zebrafish MPN model induced by NUP98-HOXA9; Applicable for small molecule screens |

[96] |

| MPN | GAL4-UAS-regulated |

fli1:GAL4-FF; UAS-GFP-HRASG12V |

Embryos | Discovery of repression of NOTCH signaling by RAS expression |

[97] |

| MPN | Transient mRNA injection | Cytoplasmic NPM1 mutant | Embryos | Increased primitive myeloid cells | [98] |

| MPN | Transient expression of mRNA |

RUNX1-CBF2T1 | Embryos | Perturbation of normal hematopoiesis | [99] |

| MPN | Heat-shock inducible Stable transgenesis |

EGFP:HSE:mMycN | 2 months | Myeloid blasts infiltration in zebrafish organs | [100] |

| MDS | TALENs | tet-2 inactivation | 11 months | Utilized genome editing technology to generate a MDS model in zebrafish |

[101] |

| MDS | TILLING | pu.1G242D | 18 months | Expanded myelopoiesis; Tested current standard therapeutics on these fish |

[71] |

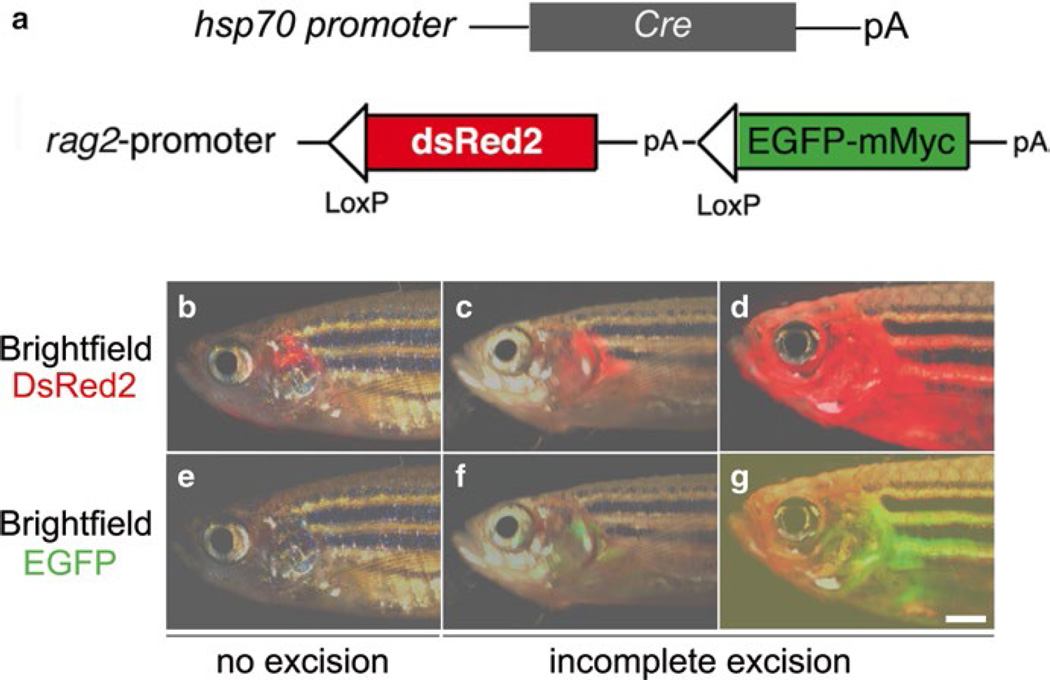

This conditional T-ALL model was further improved by outbreeding it with hsp70:Cre transgenic fish, generating rag2:loxP-dsRed2-loxP-EGFP-mMyc;hsp70:Cre double-transgenic fish (Fig. 2) [88]. Following heat-shock treatment at 3 days post fertilization (dpf), T-ALL developed in over 81% of double-transgenic fish around 120 dpf. In addition to this Cre/lox-regulated conditional T-ALL model, Gutierrez et al. developed a tamoxifen-regulated zebrafish model of T-ALL [63]. In this model, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT) treatment induces human MYC activation and T-ALL development in lymphocytes, and withdrawal of 4HT results in apoptosis and tumor regression (Fig. 3a, c). In addition to these MYC-induced T-ALL models, Chen et al. developed a zebrafish model of T-ALL by overexpressing the intracellular portion of human NOTCH1 (ICN1) under the rag2 promoter (Table 2) [83]. Constitutive murine Akt2 activation in lymphocytes also promotes T-ALL development with low penetrance in zebrafish (Table 2) [63]. In addition to transgenic T-ALL models mentioned above, Frazer et al. used ENU-mediated mutagenesis to identify three mutants—hrk, slk, and otg—developing genetic heritable T-ALL in the background of lck:EGFP transgenic fish [92] (Table 2). The gene identity of these mutations is currently under investigation.

Fig. 2.

The Cre/lox-regulated T-ALL model in zebrafish. (a) Schematic of the hsp70:Cre and rag2:loxP-dsRed2-loxP-EGFP-mMyc constructs, (b–g) Overlay of brightfield and fluorescence image of T cells expressing either dsRed2 and/or EGFP-mMyc shows T-LBL/T-ALL development in double transgenic rag2:loxP-dsRed2-loxP-EGFP-mMyc;hsp70:Cre fish, with no (red only) or incomplete (red+green) excision of loxP-dsRed2-loxP cassettes, (a–g). (Republished with permission from Wiley-Blackwell) [88

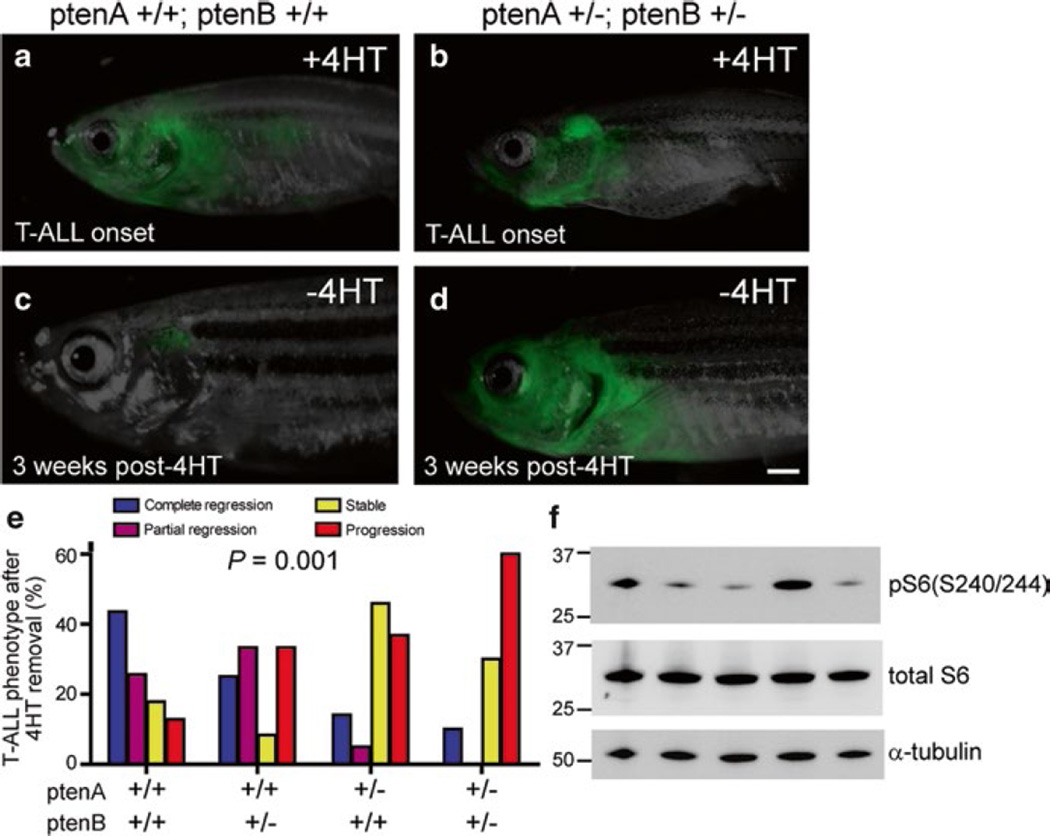

Fig. 3.

pten haploinsufficiency promotes loss of MYC transgene dependence, (a, c) One representative rag2:MYC-ER; rag2:GFP double-transgenic pten-wild-type zebrafish, shown at time of T-ALL onset (a) and 3 weeks after removal from 4HT (c). (b, d) Representative rag2:MYC-ER; rag2:GFP double-transgenic zebrafish that harbored heterozygous mutations of both ptenA and ptenB, shown at time of T-ALL onset (b) and 3 weeks after removal from 4HT (d). Bar, 1 mm. (e) Quantitation of T-ALL phenotypes after 4HT removal, based on pten genotype. Number of fish with T-ALL analyzed per genotype: ptenA +/+, ptenB +/+, n = 39; ptenA +/+, ptenB +/−, n = 12; ptenA +/−, ptenB +/+, n = 22; ptenA +/−, ptenB +/−, n = 10. (f) Western blot analysis for phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein, a marker of Akt pathway activation, in sorted T-ALL cells from five different rag2:MYC-ER pten–wild-type zebrafish in which T-ALL progressed despite MYC downregulation. Units for the molecular mass markers shown are in kD. (Republished with permission from The Rockefeller University Press) [63]

B-ALL

Modeling B-ALL in zebrafish has proven challenging. Mysteriously, oncogene overexpression driven by the rag2 promoter in both T and B lineages only leads to T-ALL development [63, 64, 81, 83, 88]. Despite multiple attempts in different laboratories using various oncogenes and promoters, the only zebrafish model of B-ALL generated to date is by overexpressing the TEL-AML1 fusion gene under ubiquitous promoters. The t(12, 21)(p13;q22) TEL-AML1 (ETV6-RUNX1) chromosomal translocation is the most common genetic rearrangement in childhood cancer, presenting in 25% of pediatric pre-B ALL (Table 1) [102]. Sabaawy et al. overexpressed the human TEL-AML1 gene under the elongation factor, β-actin, or rag2 promoters in an attempt to determine the cellular origin and molecular pathogenesis of TEL-AML1-induced B-ALL (Table 2) [82]. Interestingly, B-ALL arises in transgenic fish only when TEL-AML1 is expressed under ubiquitous promoters, but not when expressed under the lymphocyte-specific rag2 promoter. Leukemia development in these fish is associated with B cell differentiation arrest, loss of TEL expression, and an elevated Bcl-2/Bax ratio. Long disease latency (8–12 months) and low tumor penetrance (3%) in this model indicate the necessity of compound genetic alterations for B cell transformation. Thus, TEL-AML1 transgenic fish are useful for genetic screens to identify cooperating mutations that may accelerate B-ALL development in the context of TEL-AML1 expression.

AML and Other Myeloid Malignancies

The only AML model currently available was developed by the Delva group and is based on the inv(8)(p11q13) chromosomal abnormality (Tables 1 and 2) [84]. This chromosomal translocation fuses two histone acetyltransferase genes—MYST3 and NCOA2—together. Expression of the MYST3-NCOA2 fusion gene under the pu.1 (spi1) promoter led to AML development in 2 of 180 F0 mosaic fish at 14 and 26 months of life, respectively, with characteristics including an extensive invasion of myeloid blasts in the kidney. This study demonstrated the oncogenic potential of the MYST3-NCOA2 fusion gene resulting from the inv(8)(p11q13) chromosomal abnormality within an in vivo animal model.

In addition to the AML model described above, a number of zebrafish transgenic lines have been generated via the exploitation of additional genetic abnormalities in AML. Interestingly, instead of developing AML, these transgenic lines have developed myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), disorders with potential to progress to AML. The Look laboratory recently generated a zebrafish model of MDS through inactivation of the tumor suppressor Tet2 via TALENs [101]. TET2 encodes a DNA methylcytosine oxidase that is essential for demethylating DNA within genomic CpG islands [103]. TET2 loss-of-function mutations were found in multiple myeloid malignancies, including MDS, MPN, AML, and CML (Table 1) [104]. Notably, hematopoiesis in tet2 homozygous mutants is normal throughout embryogenesis and larval development, whereas progressive clonal myelodysplasia arises in aged adult fish.

One example of modeling MPN is the AML1-ETO transgenic fish generated by the Peterson group (Table 2) [94]. The AML1-ETO fusion protein results from the t(8;21)(q22;q22) chromosomal translocation in AML (Table 1). Patients expressing the AML1-ETO fusion gene exhibit an accumulation of granulocytic precursors in the bone marrow and peripheral blood [105]. Similarly, expressing the human AML1-ETO gene under the hsp70 promoter redirects myeloerythroid progenitor cells to the granulocytic cell fate, leading to the expansion of granulocyte precursors in transgenic AML1-ETO embryos. This change is accompanied by a loss of gata1 expression and an elevated pu.1 expression in myeloerythroid progenitor cells. This zebrafish model has been utilized to discover AML1-ETO-induced oncogenic signaling and to screen for compounds that exert anti-leukemic effects (see the section “Drug Discovery & Small Molecule Screens”).

An MPN model in NUP98-HOXA9 transgenic fish was developed in the Berman laboratory [96]. The NUP98-HOXA9 fusion protein is formed by translation of the 5′ region of nucleoporin 98 kDa (NUP98) on human chromosome 11 in frame to the 3′ coding sequence of homeobox A9 (HOXA9) on human chromosome 7 (Table 1) [96, 106]. Forrester et al. utilized Cre/lox recombination to conditionally express the human NUP98-HOXA9 gene under the pu.1 promoter (Table 2) [96]. Their study demonstrated that NUP98-HOXA9 expression impaired hematopoiesis, leading to an expansion of myeloid precursors [96]. Within 19–23 months, 23% of fish developed MPN. The NUP98-HOXA9 transgenic fish represents yet another tool for drug discovery and investigation of the pathogenesis of MPN. See Table 2 for details on other zebrafish MPN models [71, 93, 97, 100].

Mechanistic Insights

The availability of these models has allowed investigators to study the genetic basis of leukemia, from disease initiation to progression and drug resistance. Importantly, the molecular mechanisms underlying zebrafish leukemogenesis are strikingly similar to those in humans, providing a unique opportunity to utilize the imaging and genetic advantages intrinsic to zebrafish for continued insights into human disease. In this subsection, we will discuss several advances made by investigations of zebrafish leukemia models in conjunction with other experimental systems.

Genetic Similarities Between Human Disease and Zebrafish Models of Leukemia

As studies utilizing genome-wide approaches in zebrafish models emerged over the past few years, it became clear that gene expression signatures and genetic alterations in zebrafish models of leukemia are comparable to those in humans. Langenau et al. analyzed Myc-induced T-ALL cells in zebrafish and found that these cells upregulate scl and Imo2 oncogenes, resembling a major subtype of human T-ALL [64, 107]. Rudner et al. performed comparative genomic hybridization with Myc-induced zebrafish T-ALL cells obtained from transplanted fish, aiming to identify the recurrent genomic changes underlying disease relapse [108]. When zebrafish data were compared to a cohort of 75 published human T-ALL databases, 893 genes (67%) were found to overlap between fish and human T-ALL. Blackburn et al. performed gene expression profiling analysis on zebrafish T-ALL cells induced by activated Notch1 signaling [109]. A cross-comparison between zebrafish and human T-ALL microarray data revealed a conserved T-ALL signature shared between fish and human leukemia. Together, these studies support that zebrafish and human leukemia—particularly T-ALL—are driven and controlled by shared oncogenic pathways.

The NOTCH-MYC Axis

The NOTCH signaling pathway plays an indispensable role in hematopoiesis and T cell development [110]. Activating NOTCH1 mutations were discovered in both human and murine T-ALL samples [13, 111]. In zebrafish, overexpression of human ICN1 in the lymphocyte lineage leads to the activation of NOTCH1 downstream genes (e.g., her6 and her9) and T-ALL development [83]. Long latency and low penetrance of tumor development in this model indicates the requirement of additional cooperating mutations for leukemic transformation together with the activated NOTCH1 signaling. The oncogenic role of MYC in the lymphoid lineage was first suggested by clinical observation of the translocation of MYC into the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus (Eµ) in human Burkitt lymphoma cells [112, 113]. Subsequently, researchers generated a transgenic Eµ:Myc murine model in which B cell lymphoma rapidly arose, demonstrating MYC’s oncogenic effect in vivo [114]. In zebrafish, overexpression of the human MYC or murine Myc gene under the control of the rag2 promoter leads to the rapid development of T-ALL but not B-ALL (Table 2) [63, 64, 81, 88]. This rapid MYC-driven T-ALL development was later connected to the activation of NOTCH1 signaling as MYC was identified to be a direct transcriptional target of NOTCH1 in mammals [13, 115–119]. These studies established the important role of NOTCH and MYC in T-ALL pathogenesis. Different from its effect in mammals, Notch activation in zebrafish does not transcriptionally induce myc, thus providing a unique system to study NOTCH or MYC signaling independent from each other [109].

The PTEN-PI3K-AKT Pathway

Initial investigations of PTEN-PI3K-AKT signaling in T-ALL cells began after discovering that NOTCH1 inhibition by γ-secretase is only sensitive in a subset of T-ALL cell lines [120]. Palomero et al. elucidated the mechanisms that confer resistance of T-ALL cells to γ-secretase inhibition, leading to the discovery of NOTCH1’s regulation of PTEN expression [116]. Loss-of-function PTEN mutations confer the resistance of T-ALL cells to the inhibition of NOTCH1 signaling due to activation of PI3K-AKT signaling.

Gutierrez et al. employed their zebrafish rag2:MYC-ER transgenic fish to investigate genetic factors that are required for T-ALL maintenance [63]. In this model, tamoxifen treatment activates MYC signaling to encourage leukemogenesis. Subsequent removal of tamoxifen inactivates MYC, after which T-ALL cells undergo apoptosis rapidly in the absence of MYC (Fig. 3a, c). Importantly, when pten loss-of-function mutations are introduced into these fish, T-ALL cells no longer undergo apoptosis; instead, the disease progresses independently of MYC activation (Fig. 3b, d, e). This result can be explained by MYC’s ability to transcriptionally repress PTEN, so that PTEN upregulation following MYC inactivation is a key mediator of T-ALL regression in this context. Notably, AKT pathway activation downstream of PTEN signaling is sufficient for leukemic maintenance and progression despite inactivation of the MYC transgene (Fig. 3f). This work highlights the importance of the PTEN-PI3K-AKT pathway in MYC-independent disease maintenance, identifying mechanisms used by drug resistant T-ALL cells in the context of PTEN loss or AKT activation.

Escape of Leukemia Cells from Apoptosis

On the road to malignant transformation, cells must dampen the apoptotic response triggered by oncogenic stress. Acquired mutations, chromosomal deletions, and gene transcriptional repression or overexpression are a few means that cancer cells utilize to escape apoptosis (Table 1) [121]. Decades ago, using the murine Eµ:Myc model noted above, researchers learned the importance of Bcl-2 overexpression and suppression of the Arf-P53 apoptotic pathway in Myc-mediated transformation [122, 123]. As in mammals, bcl-2 overexpression in zebrafish dramatically accelerates Myc- or NOTCH1-induced tumor onset in the T cell lineage [83, 89]. Moreover, in a zebrafish model of B-ALL, an elevated Bcl-2/Bax ratio was observed in B-ALL cells overexpressing the TEL-AML1 fusion gene [82]. This evidence underscores the importance of escaping apoptosis during zebrafish T and B cell transformation. Surprisingly, the zebrafish does not appear to have an arf locus as evidenced by a recent study demonstrating that P53 inactivation does not impact T-ALL onset [90].

Combining the analysis of a tamoxifen-regulated T-ALL model with human T-ALL cell lines, Reynolds et al. identified repressed expression of BIM (a pro-apoptotic BCL2 family member) in both human and zebrafish T-ALL cells, allowing them to escape apoptosis [91]. The repressed BIM expression is mediated by MYC overexpression, as MYC downregulation upon tamoxifen removal restores bim expression in zebrafish T-ALL cells, promoting apoptosis and tumor regression in vivo. Alternatively, AKT activation can lead to the suppression of BIM expression. When human T-ALL cells were treated with MYC or PI3K-AKT pathway inhibitors, BIM expression was upregulated and subsequently promoted T-ALL cell apoptosis. These results indicate that the identifying molecular mechanisms that leukemic cells use to escape apoptosis, and restoration of these apoptotic pathways (e.g. BIM-mediated apoptosis), represents a promising therapeutic approach.

Genetic Basis of T-LBL Dissemination to T-ALL

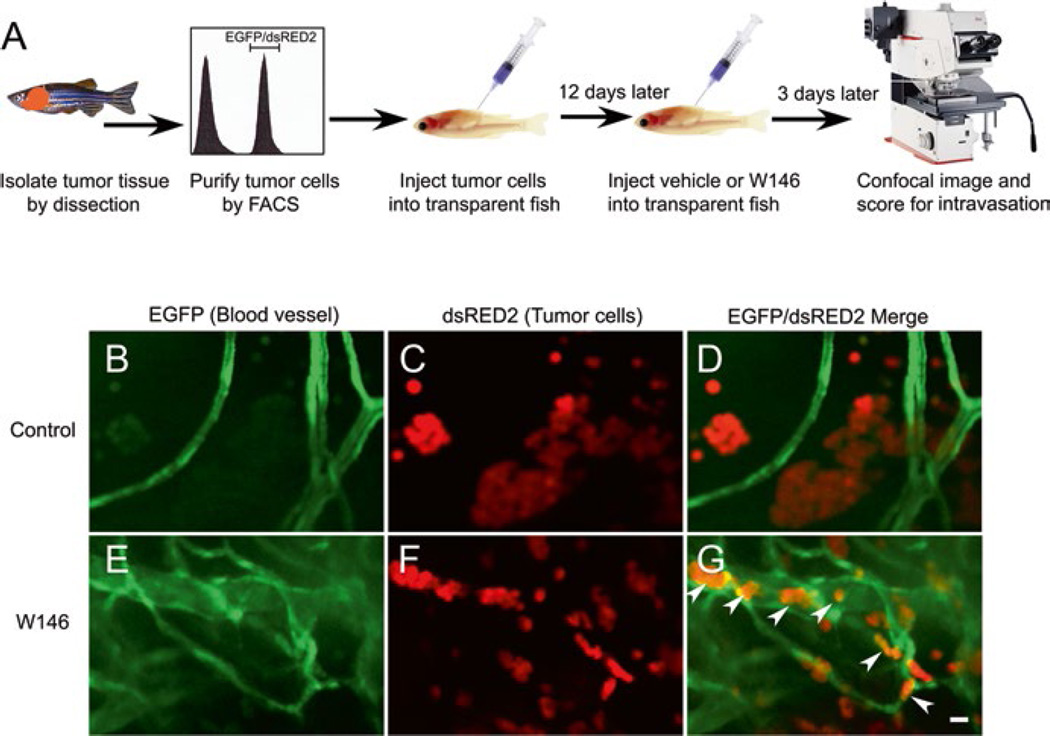

T-ALL and T-cell acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LBL) have distinct clinical presentations. T-ALL is defined by a bone marrow biopsy with a composition of ≥30% T-lymphoblasts, while T-LBL is defined by a mediastinal mass where <30% of blasts are in circulation. Feng et al. utilized a Cre/lox-regulated T-ALL model in combination with clinical patient sample analyses to investigate the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the progression of T-LBL to T-ALL (Figs. 2 and 4) [88, 89]. Interestingly, when bcl-2 was overexpressed in this Myc-induced T-ALL model, despite the rapid onset of the malignant transformation, the disease remained localized and failed to disseminate, compared to fish expressing Myc alone. They demonstrated that both human and zebrafish T-LBL cells with increased BCL2 levels possess a distinct cellular phenotype including impaired vascular invasion, metabolic stress, and autophagy. This T-LBL phenotype results from elevated levels of singhosine-1 phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1, promoting homotypic cell-cell adhesion and blocking intravasation of tumor cells. Treatment with the S1P1-antagonist W146 promotes intravasation of bcl-2-overexpressing T-LBL cells in zebrafish (Fig. 4). Moreover, AKT activation overcomes this intravasation blockade and promotes the rapid dissemination of T-LBL to T-ALL. This work elucidated the molecular events underlying the progression of T-LBL to T-ALL, and helped to explain clinical disparities between these two disease entities.

Fig. 4.

The selective S1P1 antagonist W146 promotes intravasation of bcl-2-overexpressing T-LBL cells in vivo. (a) Schematic drawing of the experimental strategy, (b–g) Confocal images of EGFP-labeled blood vessels (b, e), dsRed2-labeled lymphoma cells (c, f), and the merged images of a vehicle-treated (d; n = 29) and a W146-treated transplanted animal (g; n= 18) demonstrate that W146 treatment promotes intravasation of bcl-2-overexpressing lymphoma cells (arrowheads) in vivo (cf. g to d). Note that W146 treatment also inhibited the in vivo formation of lymphoma cell aggregates (cf. f to c). Scale bar for (b)–(g), 10 mM. (Republished with permission from Elsevier) [89]

Lineage-Specific TEL-JAK2 Action

The human TEL (ETV6)-JAK2 fusion gene results from translocations between JAK2 (9p24) and TEL (12p13) in cases of T-ALL and CML (Table 1) [124]. In T-ALL cells, this translocation fuses exon 5 of TEL with exon 9 of JAK2, whereas the translocation in CML cells fuses exon 5 of TEL with exon 12 of JAK2 [124]. To better understand the role of TEL-JAK2 translocation in leukemogenesis, Onnebo et al. generated transgenic fish expressing the zebrafish tel-jak2 fusion genes, mimicking different leukemic variants of human TEL-JAK2 fusion genes [125]. Interestingly, T-ALL-derived tel-jak2 significantly perturbed lymphopoiesis. Conversely, CML-derived tel-jak2 led to more myelopoiesis-associated defects. This experimental evidence supports the idea that TEL-JAK2 exerts lineage-specific oncogenic effects.

Leukemia Transplantations

Tumor transplantations are important techniques for understanding the pathophysiology of cancer. Given their high fecundity and unique imaging advantages, zebrafish make excellent transplantation models. Zebrafish tumor cells have been transplanted (i.e. allotransplantation, or transplanted from one zebrafish to another) to quantify leukemia-propagating cells (LPC) and dissect the molecular mechanisms underlying LPC self-renewal and drug resistance [86, 126]. Moreover, human leukemia cell lines or patient cells can be transplanted into zebrafish embryos to generate various xenograft models (i.e., transplanted from one species to another), providing efficient in vivo tools for screening novel anti-leukemic therapeutics and determining compound efficacy and toxicity.

Syngeneic Transplantation and Assessing LPC Function in Zebrafish T-ALL

Although zebrafish transplantation experiments started as early as the 1990s [127], a major hurdle in their broader application was the need for immunosuppression. Recipient fish are often subjected to γ-irradiation to ablate immune cells, experiencing high rates of mortality due to immunosuppression-related complications. To overcome this limitation, Smith et al. generated a Myc-induced T-ALL model in syngeneic zebrafish (CGI strain), allowing the transplantation of T-ALL cells into immune-matched CGI sibling fish without the need for immunosuppression [86]. This method enabled investigators to quantify the frequency of LPC using limiting-dilution cell transplantation in zebrafish. Their research demonstrated that T-ALL can be initiated from a single cell, and such LPCs are abundant in T-ALL despite differences in their individual tumor-initiating potential. While this research was based on T-ALL, the same strategy can be applied to other zebrafish cancer models. Identification of cancer stem cells such as LPCs and elucidation of molecular mechanisms underlying their self-renewal may reveal therapeutic strategies directed against disease relapse.

The NOTCH1 and AKT Signaling in LPC

To rapidly assess the functional role of two to three genes in F0 fish without the need for stable transgenic fish, Langenau et al. established a co-injection strategy to introduce multiple transgenes into one-cell-stage embryos, permitting transgenes to synergize for tumorigenesis [68]. Combining the co-injection strategy with limiting-dilution cell transplantation, Blackburn et al. determined the effects of NOTCH1 signaling on the self-renewal of LPCs [109]. Utilizing a zebrafish Notch1 defective in its ability to transcriptionally activate Myc, they demonstrated that NOTCH1 can expand pre-leukemic clones; however, NOTCH signaling does not increase the overall frequency of LPCs, either alone or in collaboration with MYC. These results suggest that the main function of NOTCH signaling in T-ALL is to promote the proliferation of premalignant T cells, of which only a small number acquire additional mutations and become LPCs.

To identify mutations driving leukemic clonal evolution and intratumoral heterogeneity, Blackburn et al. performed a cell transplantation screen based on phenotypic differences among leukemic clones (Fig. 5) [126]. Using this approach, after serial clonal selection, they identified AKT activation in leukemic cells with elevated LPC frequency. Indeed, enforced AKT activation increased LPC frequency by enhancing mTORC1 activity and shortened tumor latency by promoting MYC stability. However, MYC stabilization alone was not sufficient to promote LPC frequency. AKT activation promoted treatment resistance, and this resistance could be overcome by the combined treatment of an AKT inhibitor and dexamethasone. These results indicate that continuous selection in T-ALL cells promotes clonal evolution and disease progression, and that clonal selection can occur before therapeutic intervention.

Fig. 5.

Clonal evolution drives intratumoral heterogeneity and can lead to increased LPC Frequency. (a) A schematic of the cell transplantation screen designed to identify phenotypic differences between single leukemic clones. (b, c) Schematic of results from primary T-ALL #1 (b) and T-ALL #9 (c). *Denotes a significant increase in LPC frequency from monoclonal primary to secondary transplant (p = 0.02). **Denotes a significant increase in LPC frequency from monoclonal primary transplant T-ALL compared with tertiary transplanted leukemia (p<0.0001). Clones are color coded based on Tcrβ-rearrangements. (Republished with permission from Elsevier) [126]

Zebrafish Xenograft Models of Human Leukemia

Xenograft models are widely applied in rodents to investigate tumor proliferation and drug sensitivity. Zebrafish embryos are particularly suited for xenografting given the following: (a) zebrafish lack a mature adaptive immune system until 4 weeks post-fertilization [128], allowing transplantation without the need for immunosuppression; (b) zebrafish are optically transparent and, as with injected cells, can be specifically labeled with various fluorochromes, allowing visualization of in vivo cell-cell interactions; and (c) zebrafish are highly fecund and inexpensive to maintain, permitting high-throughput drug discovery screening. Since 2011, researchers have been transplanting human leukemia cell lines and primary leukemic cells into zebrafish embryos (48 hpf) to screen novel compounds and to assay drug efficacy and toxicity for preclinical validation (see the section “Drug Discovery & Small Molecule Screens”).

Drug Discovery & Small Molecule Screens

Drug discovery and development is a time-consuming and expensive process, in some instances costing upwards of $1 billion over 10–15 years as a drug progresses from early target identification through clinical trials and market approval [129]. Current techniques in drug discovery allow researchers to generate an enormous number of potential targets for further development, but correctly identifying ‘hits’—compounds that will ultimately prove successful in clinical trials—continues to pose enormous challenges. Mammalian and invertebrate animal models are often used in this screening process, but mammals are costly and cumbersome, and invertebrates are less physiologically relevant to humans. Therefore, non-mammalian vertebrate systems combining high-throughput whole-organism testing and rapid phenotypic selection—with the added benefit of preliminary toxicological readout—holds obvious appeal for improving time- and cost-efficiency. Zebrafish are compatible with such a system; they share useful physiological characteristics with mammals; their small embryos and juveniles permit multiplex techniques; and their adequately developed organs allow toxicities to be identified early during screening [130]. Zebrafish drug screens can be performed with chemical libraries utilizing wild-type, mutant, transgenic, or xenografted zebrafish embryos. Recent advances using zebrafish transgenic and xenograft models of leukemia are discussed as follows.

Small Molecule Screens Using Transgenic Leukemia Models

Chemical library screening for leukemic research began in 2010 when a zebrafish Myc-induced T-ALL model demonstrated its capacity to recapitulate clinical responses to approved therapeutics (e.g. cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone) as observed in humans [131]. Since then chemical library screening has been applied to zebrafish leukemia models including an AML model and multiple T-ALL models [95, 132, 133].

Yeh et al. performed one of the first chemical library screens with a transgenic line aiming to model AML [95]. Their model expressed an oncogenic AML driver of hematopoietic differentiation termed AML1-ETO, a fusion protein resulting from the t(8;21) translocation (Table 1). The investigators hypothesized that inhibition of the self-renewal ability of hematopoietic stem cells could provide a complementary therapy to the inhibition of cell proliferation (a common approach of AML therapy). As described earlier (Table 2), the oncogenic AML1-ETO fusion protein was expressed under the hsp70 promoter in homozygous fish outcrossed with wild-type fish. Their screen utilized five heterozygous embryos per well in 96-well plates collectively treated with the SPECTRUM compound library—comprised of drugs (60%), natural products (25%), and other bioactive components (15%). Plates were heat shocked to induce AE expression within embryos, thereafter assayed for phenotypic change. Notably, use of the hsp70 promoter resulted in false-positive hits when select screening agents interfered with proteins related to the heat shock response; the authors suggest using a different promoter to avoid this pitfall. Follow-up study with their lead hit—the COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide—identified a previously unknown role for COX-2 and β-catenin in AE-mediated hematopoietic differentiation. Specifically, nimesulide antagonizes the effects of AML1-ETO on hematopoietic differentiation by interrupting the COX-2 dependent β-catenin signaling pathway [95]. Therefore, future studies might aim to manipulate COX-2 or β-catenin signaling in AML patients with AE-associated pathology.

Whereas Yeh et al. performed chemical screening with a library of characterized compounds, Ridges et al. performed the first embryonic zebrafish screen using a library of compounds with unknown activity [95, 133]. Lacking a model manifesting T-ALL during embryogenesis, Ridges et al. used a sequential approach by identifying compounds with activity against immature zebrafish T cells—with the idea that these cells are most similar to leukemic T lymphoblasts—and thereafter validated hits for anti-neoplastic effect in an adult zebrafish Myc-induced T-ALL model. Their lead hit—lenaldekar— affects the PI3 kinase/AKT/mTOR pathway and shows selective activity against malignant hematopoietic cell lines and primary leukemias [133].

Motivated by the need for NOTCH-independent therapeutics, Gutierrez et al. modified a tamoxifen-regulated MYC-induced T-ALL model in a fluorescence-based screen using dsRed2 expression in thymocytes as a screen read-out (Fig. 6) [81, 132]. With the ability to select for embryos expressing MYC and to image the intensity of their thymic dsRed2 fluorescence, they identified perphenazine in a screen of FDA-approved compounds. Interestingly, in a complementary cell line screen, perphenazine was identified for its synergy with NOTCH inhibitors [132]. Perphenazine is best-known as an inhibitor of dopamine receptor signaling, but the biologic target mediating its anti-leukemic effect appeared to be unrelated to any of its known molecular targets. Using a novel proteomics approach, the tumor suppressor protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) was found to be a target of perphenazine that is activated by perphenazine binding. Their data provided evidence that activators of PP2A (e.g. perphenazine) in combination with NOTCH-dependent therapeutics might provide an effective T-ALL therapy [132].

Fig. 6.

Zebrafish screen for small molecules that are toxic to MYC-overexpressing thymocytes. (a) Primary screen design. (b) Hits from the primary screen. Arrow denotes the result obtained with perphenazine (c). Representative images of DMSO (control) or perphenazine treated zebrafish larvae. (d) Dose response curve from secondary screen of perphenazine, with six zebrafish larvae treated per concentration. Drug doses higher than 10 µM induced general toxicity (not shown). Error bars = SD. (Modified and republished with permission from American Society for Clinical Investigation) [132]

Leukemic Xenograft Models in Drug Discovery

When transgenic zebrafish models for particular leukemias are unavailable for screening, zebrafish xenograft models are an alternative and have moved into the mainstream since early studies in 2011 [134]. Creating these models involves a labor-intensive xenografting procedure, requiring the manual injection of cells prior to experimental manipulation. Pruvot et al. were the first to establish zebrafish xenograft models of human leukemia for drug discovery [134]. After performing zebrafish xenografting, the investigators aimed to identify drug-induced decreases in leukemic burden. When flow cytometry could not provide sufficient sensitivity to quantify cell proliferation, human L32 and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase gene expression was measured as a correlate of drug-induced change in leukemic burden. In an effort to improve this quantification, Corkery et al. developed a methodology to enzymatically dissociate drug-treated embryos followed by a semiautomatic quantification of fluorescence intensity using a semi-automated macro (Image J) [135]. In this way, leukemic cells could be quantified directly. Such studies have provided proof-of-principal and validated the utility of zebrafish xenograft models for small molecule screening and anti-leukemic drug discovery [134, 135].

Further advancing the applicability of zebrafish xenografting, Zhang et al. validated a model for the identification of therapeutics targeting leukemic stem cells (LSCs), motivated by the clinical persistence of this population following even complete cytogenetic responses in CML [136, 137]. Their method required LSC-xenografted embryos and utilized a novel, highly automated fluorescence-imaging process to determine both cancer cell proliferation and cell migration, reducing labor and increasing throughput. Though only selective clinical therapeutics were tested (e.g. imatinib, dasatinib, parthenolide, etc.), their screen recapitulated these drugs’ inhibition of LSCs in zebrafish xenograft models—as previously evidenced by both in vitro and murine studies—thus validating their methodology for future anti-LSC drug discovery.

The utility and impact of zebrafish-based drug discovery is growing each year. The validation of leukemic zebrafish models and their ability to identify lead compounds like lenaldekar promote further study and methodological development. Although thousands of compounds were screened in the studies discussed above, their setups were largely manual and their execution required years of work. High-throughput, fully automated robotic methods are in development and promise to automate the selection, placement, and injection of zebrafish embryos with DNA and cancer cells, among other desired materials [138–140].

Summary & Future Perspectives

Since the birth of the first zebrafish model of leukemia (T-ALL) in 2003 [81], zebrafish have contributed greatly to leukemia research. Multiple different zebrafish lines have been generated to model various human leukemias and pre-leukemic diseases, including T-ALL, B-ALL, AML, MPN, and MDS. The ease with which the zebrafish can be genetically modified and subsequently imaged has allowed investigators to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis, as well as leukemic progression and maintenance. In fact, investigation of zebrafish models of leukemia has significantly improved our understanding of leukemogenesis. Examples of the advances include: (a) knowledge of a shared genetic signature between human and zebrafish T-ALL; (b) the importance of NOTCH and MYC in T-ALL pathogenesis [13, 63, 64, 81, 83, 88, 115–119]; (c) the contribution of the PTEN-PI3K-AKT pathways to T-ALL drug resistance in the context of MYC-independent disease [63]; (d) BIM-mediated apoptosis as an avenue for therapy [91]; (e) genetic factors underlying T-LBL to T-ALL dissemination [89]; and (f) the expression of disease-specific fusion proteins [125]. The development of syngeneic transplantation has allowed functional assessment of LPCs in zebrafish, and a transplantation-based screen has elucidated the role of AKT in LPC clonal evolution and treatment resistance [86, 126]. Exploiting high-throughput capabilities of the zebrafish system, investigators have performed small molecule screens and identified multiple agents with anti-leukemic activity, including nimesulide, lenaldekar, and perphenazine [95, 132, 133]. These advances in zebrafish modeling and disease studies have helped to overcome initial skepticism concerning their utility in cancer research, establishing an important biomedical role for this humble organism.

Moving forward, much additional research can be done using the zebrafish. Most zebrafish models of leukemia recapitulate human T-ALL, and although models of pre-B-ALL and AML exist, they have only limited utility. Multiple models of MPN and MDS have been generated, but these fish fail to develop AML. This is likely due to single genetic manipulation in these zebrafish lines, whereas multiple genetic alterations are required for leukemogenesis in humans. Given technological advances, it is now possible to simultaneously manipulate multiple genes within the same cell lineage. We anticipate new zebrafish models of leukemia—including T-ALL, B-ALL, AML, CLL, and CML—will be generated through the use of both transgenic and genome editing technologies, resulting in the overexpression of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressors. These new models will provide important mechanistic insight into leukemic initiation and progression. Despite scientists’ current capacity to conduct successful small molecule screening with zebrafish embryos, the process remains limited by the necessity to manually deposit embryos into multiple wells, as well as the number of embryos that can be manually injected when xenograft models are required. Future automation and standardization of these procedures will enable truly high-throughput small molecule screening, which could eventually contribute to personalized medicine. For example, ex vivo screening of an individual patient’s leukemia samples could be applied in a zebrafish xenograft model for the testing of multiple drugs and drug combinations, and the readout would inform clinicians on measures of both drug potency and toxicity, improving therapy selection on a case-by-case basis.

Zebrafish have been welcomed into the oncological research community for their usefulness in delineating factors contributing to tumorigenesis and treatment resistance, as well as for identifying novel agents for experimental therapeutics. However, due to their evolutionary distance from humans, results from zebrafish models require further validation in mammalian models, particularly as candidate therapeutics approach clinical development. Moreover, gene duplication and functional redundancy within the zebrafish genome pose challenges for gene inactivation studies, and antibody production in zebrafish remains daunting due to surface glycosylation modification of proteins. Despite these limitations, maximizing their strengths in combination with the use of mammalian systems, zebrafish will make waves in an ocean of unexploited oncological knowledge, especially in leukemic research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joseph Hirsch for editorial assistance, and Leah Huiting and Dr. Nicole M. Anderson for helpful comments and suggestions. N.R.H is supported by a training grant (T32GM008541) from the National Institutes of Health. H.F. is supported by a grant (R00CA134743) from the National Institutes of Health, a career development grant from the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, a Karin Grunebaum Faculty Fellowship from the Karin Grunebaum Cancer Foundation, a Ralph Edwards Career Development Professorship from Boston University, and an institutional grant (IRG –72-001-36-IRG) from the American Cancer Society.

Abbreviations

- 4HT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- B-ALL

B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CML

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- CRISPR/Cas9

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9

- dpf

Days post fertilization

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- ENU

N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- GMP

Granulocyte/macrophage progenitors

- HOXA9

Homeobox A9

- HSCs

Hematopoietic stem cells

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- ICN1

Intracellular portion of human NOTCH1

- LED

Light emitting diode

- LP

Lymphoid progenitor (cells)

- LPC

Leukemia-propagating cells

- LSCM

Laser scanning fluorescent confocal microscopy

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- MEP

Megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors

- MP

Myeloid progenitor (cells)

- MPN

Myeloproliferative neoplasm

- NUP98

Nucleoporin 98 kDa

- PP2A

Protein phosphatase 2

- Pro-B

Pro-B-lymphocytes

- Pro-T

Pro-T-lymphocytes

- RFP

Red fluorescent protein

- S1P1

Singhosine-1 phosphate receptor 1

- SDCM

Spinning disc confocal microscopy

- TALENs

Transcription activator-like effector nucleases

- T-ALL

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- TET2

Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2

- TILLING

Targeting induced local lesions IN Genomes

- T-LBL

T-cell acute lymphoblastic lymphoma

- ZFNs

Zinc finger nucleases

Contributor Information

Nicholas R. Harrison, Email: nichar@bu.edu.

Fabrice J.F. Laroche, Email: laroche@bu.edu.

Alejandro Gutierrez, Email: Alejandro.Gutierrez@childrens.harvard.edu.

Hui Feng, Email: huifeng@bu.edu.

References

- 1.Cancer Facts & Figures. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seiter K. ALL. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia - Medscape Reference. 2014;2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seiter K. AML. Acute Myelogenous Leukemia - Medscape Reference. 2014;2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Vlierberghe P, Ferrando A. The molecular basis of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3398–3406. doi: 10.1172/JCI61269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi S, Koike M, Seriu T, Bartram CR, Slater J, Park S, Miyoshi I, Koeffler HP. Homozygous deletions at 9p21 in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia detected by microsatellite analysis. Leukemia. 1997;11(10):1636–1640. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Lawrence MS, Wan Y, Stojanov P, Sougnez C, Stevenson K, Werner L, Sivachenko A, DeLuca DS, Zhang L, Zhang W, Vartanov AR, Fernandes SM, Goldstein NR, Folco EG, Cibulskis K, Tesar B, Sievers QL, Shefler E, Gabriel S, Hacohen N, Reed R, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Lander ES, Neuberg D, Brown JR, Getz G, Wu CJ. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2497–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-Subero JI, Lopez-Otin C, Campo E. Genetic and epigenetic basis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20(4):362–368. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32836235dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baliakas P, Iskas M, Gardiner A, Davis Z, Plevova K, Nguyen-Khac F, Malcikova J, Anagnostopoulos A, Glide S, Mould S, Stepanovska K, Brejcha M, Belessi C, Davi F, Pospisilova S, Athanasiadou A, Stamatopoulos K, Oscier D. Chromosomal translocations and karyotype complexity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic reappraisal of classic cytogenetic data. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(3):249–255. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson B, Fioretos T, Mitelman F. Cytogenetic and molecular genetic evolution of chronic myeloid leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2002;107(2):76–94. doi: 10.1159/000046636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rumpold H, Webersinke G. Molecular pathogenesis of Philadelphia-positive chronic myeloid leukemia - is it all BCR-ABL? Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11(1):3–19. doi: 10.2174/156800911793743619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Radtke I, Phillips LA, Dalton J, Ma J, White D, Hughes TP, Le Beau MM, Pui CH, Relling MV, Shurtleff SA, Downing JR. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453(7191):110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JP, Silvennan LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Blacklow SC, Look AT, Aster JC. Activating mutations of NOTCH 1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306(5694):269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neil J, Grim J, Stack P, Rao S, Tibbitts D, Winter C, Hardwick J, Welcker M, Meijerink JP, Pieters R, Draetta G, Sears R, Clurman BE, Look AT. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson BJ, Buonamici S, Sulis ML, Palomero T, Vilimas T, Basso G, Ferrando A, Aifantis I. The SCFFBW7 ubiquitin ligase complex as a tumor suppressor in T cell leukemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1825–1835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullighan CG. Molecular genetics of B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3407–3415. doi: 10.1172/JCI61203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcucci G, Haferlach T, Dohner H. Molecular genetics of adult acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):475–486. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung SS. Genetic mutations in acute myeloid leukemia that influence clinical decisions. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21(2):87–94. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quesada V, Ramsay AJ, Lopez-Otin C. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with SF3B1 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2530. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1204033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landau DA, Stewart C, Reiter JG, Lawrence M, Sougnez C, Brown JR, Lopez-Guillermo A, Gabriel S, Lander E, Neuberg DS, Lopez-Otin C, Campo E, Getz G, Wu CJ. Novel putative driver gene mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results from a combined analysis of whole-exome sequencing of 262 primary CLL samples. Blood. 2014;124(21):1952–1952. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawyers CL. Chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(17):1330–1340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904293401706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, O’Brien S, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM. The biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):164–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quintas-Cardama A, Cortes J. Molecular biology of bcr-abl1-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(8):1619–1630. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besa EC. CML. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia - Medscape Reference. 2014;2014 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosen N, Maeda T, Hashii Y, Tsuboi A, Nishida S, Nakata J, Nakae Y, Takashima S, Oji Y, Oka Y, Kumanogoh A, Sugiyama H. Vaccination strategies to improve outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplant in leukemia patients: early evidence and future prospects. Expert Rev Hematol. 2014;7(5):671–681. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2014.953925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ai J, Advani A. Current status of antibody therapy in ALL. Br J Haematol. 2014;168:471–480. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balducci L. The geriatric cancer patient: equal benefit from equal treatment. Cancer Control. 2001;8(2 Suppl):1–25. quiz 27-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslin S. Cytokine-release syndrome: overview and nursing implications. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(1 Suppl):37–42. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.S1.37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mavroudis D, Barrett J. The graft-versus-leukemia effect. Curr Opin Hematol. 1996;3(6):423–429. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199603060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezvani AR, Storb RF. Separation of graft-vs.-tumor effects from graft-vs.-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Autoimmun. 2008;30(3):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wayne AS, Fitzgerald DJ, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Immunotoxins for leukemia. Blood. 2014;123(16):2470–2477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-492256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burkhardt UE, Hainz U, Stevenson K, Goldstein NR, Pasek M, Naito M, Wu D, Ho VT, Alonso A, Hammond NN, Wong J, Sievers QL, Brusic A, McDonough SM, Zeng W, Perrin A, Brown JR, Canning CM, Koreth J, Cutler C, Annand P, Neuberg D, Lee JS, Antin JH, Mulligan RC, Sasada T, Ritz J, Soiffer RJ, Dranoff G, Alyea EP, Wu CJ. Autologous CLL cell vaccination early after transplant induces leukemia-specific T cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):3756–3765. doi: 10.1172/JCI69098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CAR T-Cell Therapy: Engineering Patients’ Immune Cells to Treat Their Cancers. National Cancer Institute; 2014. Accessed Web Page 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carella AM, Branford S, Deininger M, Mahon FX, Saglio G, Eiring A, Khorashad J, O’Hare T, Goldman JM. What challenges remain in chronic myeloid leukemia research? Haematologica. 2013;98(8):1168–1172. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.090381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin L, Smith BD, Tsai HL, Yaghi NK, Neela PH, Moake M, Fu J, Kasamon YL, Prince GT, Goswami M, Rosner GL, Levitsky HI, Hourigan CS. Induction of high-titer IgG antibodies against multiple leukemia-associated antigens in CML patients with clinical responses to K562/GVAX immunotherapy. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e145. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davidson AJ, Zon LI. The ‘definitive’ (and ‘primitive’) guide to zebrafish hematopoiesis. Oncogene. 2004;23(43):7233–7246. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]