Abstract

Background/Aims

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection with standard triple therapy (TT) has declined primarily because of increased antibiotic resistance. Sequential therapy (ST) has been suggested as an alternative to TT for the first-line treatment of H. pylori. The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy of ST with TT.

Methods

This was a multicenter, randomized open-label trial performed at nine centers in Korea. Patients with H. pylori infection were randomly assigned to receive either 7 day TT or 10 day ST. Eradication rates, drug compliance, and adverse events were compared among the two regimens.

Results

A total of 601 patients were enrolled between March 2011 and September 2014. The intention-to-treat eradication rates were 70.8% for TT and 82.4% for ST (p=0.001). The corresponding per protocol eradication rates were 76.9% and 88.8% for TT and ST, respectively (p=0.000). There were no statistically significant differences between the two regimens with respect to drug compliance and adverse events.

Conclusions

ST achieved better eradication rates than TT as a first-line therapy for H. pylori eradication in Korea.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Drug resistance, Disease eradication

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a known cause of gastritis, peptic ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma), and gastric cancer.1,2 Eradication of H. pylori is essential for the treatment of these diseases and is currently recommended in numerous guidelines.3–6 Most international guidelines recommended triple therapy (TT) regimens consisting of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin, and amoxicillin/metronidazole for at least 7 days for eradication of H. pylori.7–10 However the eradication rates of TT has decreased to unacceptable levels of less than 80% in the past decade due to increased H. pylori resistance to antibiotics.11,12 Although the seroprevalence rate of H. pylori has been reported to be decreasing in Korea, it is still very common infecting more than half of the adult population.13

The TT regimen is recommend as first line therapy in the recent Korean guidelines and is the only regimen reimbursed by the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS).14 However, the eradication rates of TT has been reported to be declining in Korea similar to the trend shown in other countries.15,16

The sequential therapy (ST) consists of a PPI and amoxicillin for the first 5 days followed by a PPI plus clarithromycin and metronidazole (or tinidazole) for the following 5 days.17 The ST regimen has been suggested as an alternative first line regimen and several systematic reviews have found the ST to be superior to TT for eradication of H. pylori.18–21 However, clarithromycin resistance is reported to be as high as 37.3% in Korea.22 A meta-analysis found that although ST achieved higher eradication rates than the TT regimens, its eradication rate was lower in Korea compared with previous reports.23 However, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis were either single center studies or locoregional studies. Thus, we decided to perform a nationwide study comparing the eradication rates of ST with TT to find out if ST can replace TT as first line therapy in Korea

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design and population

This was a multicenter, randomized, open-label, and double-arm study. Patients with confirmed H. pylori infection were enrolled from nine tertiary hospitals from March 2011 to September 2014 (Fig. 1). Currently, the NHIS reimburses eradication therapy for patients diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease or gastric MALToma. Consecutive patients (19 to 75 years of age) who had received endoscopy at each hospital and who met the criteria for eradication by NHIS were candidates for inclusion in the study. Patients who had received endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer were also included in our study. Exclusion criteria included use of PPI, H2-receptor antagonist, bismuth preparation and antibiotics 2 weeks before enrollment, prior eradication treatment, history of gastrectomy, and presence of severe comorbidities or malignancy. Patients deemed inappropriate for inclusion by the investigator were excluded, as were patients who refused to participate in the study. All included patients provided written informed consent prior to their participation. The study was approved by Korean Ministry of Drug and Food Safety (11930) along with the ethics committees at each participating hospital. This study was registered at Clinical Research Information Service (KCT0000378).

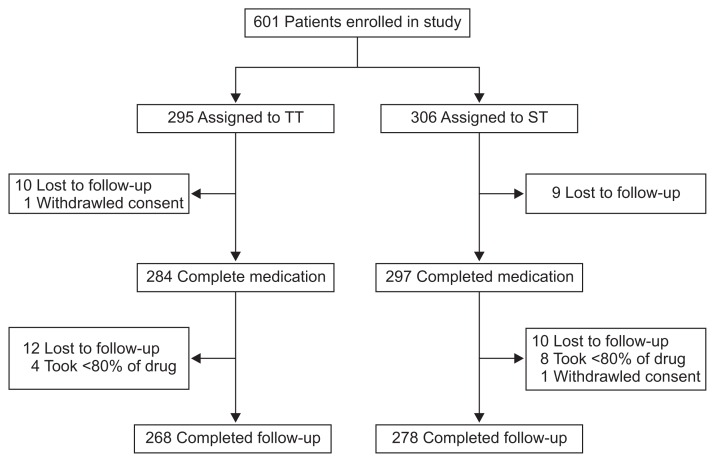

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the participants included in the study.

TT, triple therapy; ST, sequential therapy.

2. Detection of H. pylori infection and confirmation of eradication

All patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before enrollment in this study. H. pylori infection was defined as positive if the results of one of the following tests were positive: histological assessment of H. pylori by modified Giemsa stain according to the Sydney system, and rapid urease test using samples from the antrum and distal corpus. H. pylori eradication was evaluated by the two tests used for diagnosis or by 13C-urea breath test 4 weeks after completion of treatment.

3. Randomization and intervention

Patients were randomly assigned to two treatment groups in a 1:1 ratio using a computerized random sequence when the patient agreed to participate in this study. The TT group received a full dose PPI such as lansoprazole 30 mg or pantoprazole 40 mg, amoxicillin 1 g, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The ST group received a full dose PPI and amoxicillin 1 g twice daily for 5 days, followed by a full dose PPI, clarithromycin 500 mg, and metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 5 days. Compliance and adverse events were assessed by interview after the end of the treatment.

4. Measurements and outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was H. pylori eradication rate in the ST group compared to the TT groups. Secondary endpoints were adverse effects and compliance to treatment in the TT and ST groups.

5. Statistical analysis

The eradication rate of ST and conventional TT was assumed to be 80% and 70%, respectively.23 The sample size needed to detect a difference of 10% in the eradication between the two regimens with a power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05 was calculated. A drop-out rate of 20% was anticipated. The final calculated sample size was 290 patients for each group. For intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, all patients who took the prescription for eradication therapy were included. For the per protocol (PP) analysis, patients who had taken <80% of their medication were excluded as well as patients who did not return for follow-up. Chi-square and Student t-tests were used to compare proportions and means for normally distributed data. For all tests, a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

A total of 601 patients were enrolled in our study, with 295 randomly assigned to the TT group and 306 to the ST group (Fig. 1). Nineteen patients were lost to follow-up and one patient withdrew consent after receiving their eradication medicine. Among the remaining 581 patients, 22 were lost to follow-up, 12 took <80% of their medication, and one withdrew consent. Therefore the final PP population consisted of 546 patients. Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline were similar between the two treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

| Variable | Triple therapy (n=295) | Sequential therapy (n=306) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 54.07±12.6 | 54.01±11.8 | 0.955 |

| Male sex | 173 (58.6) | 188 (61.4) | 0.484 |

| Reason for eradication | 0.764* | ||

| Gastric ulcer | 148 | 140 | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 102 | 114 | |

| Gastric+duodenal ulcer | 13 | 15 | |

| Endoscopic treatment of EGCa | 29 | 36 | |

| MALToma | 1 | 0 | |

| Others | 2 | 1 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

EGCa, early gastric cancer; MALToma, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.

Fisher exact test.

In the ITT population, eradication rates were 70.8% in the TT group and 82.4% in the ST group (p=0.001) (Table 2). In the PP population, eradication rates were 76.9% with TT and 88.8% with ST (p=0.000). Bitter taste was the most common adverse effect (Table 3). The overall adverse effect rates were similar in the TT and ST groups (43.0% vs 44.4%, p=0.718). Adherence to the medication was also similar between the TT and ST groups (98.5% vs 97.2%, p=0.280).

Table 2.

Eradication Rates and Compliance of Standard Triple Therapy and in Sequential Therapy

| Triple therapy | Sequential therapy | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eradication of first line treatment | |||

| ITT | 209/295 (70.8) | 252/306 (82.4) | 0.001 |

| PP | 206/268 (76.9) | 247/278 (88.8) | 0.000 |

Data are presented as number (%)

ITT, intention-to-treat; PP, per protocol.

Table 3.

Adverse Event Profiles of Triple Therapy and Sequential Therapy

| Triple therapy | Sequential therapy | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bitter taste | 81 (28.5) | 72 (24.2) | 0.242 |

| Nausea | 14 (4.9) | 34 (11.4) | 0.004 |

| Diarrhea | 34 (12.0) | 22 (7.4) | 0.062 |

| Headache | 2 (0.7) | 8 (2.7) | 0.065 |

| Epigastric discomfort | 8 (2.8) | 11 (3.7) | 0.548 |

| General weakness | 6 (2.1) | 7 (2.4) | 0.842 |

| Others | 9 (3.1) | 13 (4.4) | 0.446 |

| Any adverse events | 122 (43.0) | 132 (44.4) | 0.718 |

| Adherence | 268 (98.5) | 278 (97.2) | 0.280 |

Data are presented as number (%).

DISCUSSION

ST demonstrated better eradication rates than TT in both ITT and PP analyses in the present nationwide study. Adverse events and treatment compliance were not statistically different between the two treatments. The efficacy of ST is challenged by metronidazole resistance and dual resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole.24 In Korea, resistance to both antibiotics is high with resistance rates of 16.0% to 37.0% for clarithromycin and 35.8% to 56.3% for metronidazole.22,25,26 Dual resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole is reported to be 3.2%.25 The main reason that TT is still recommended as first-line therapy in Korea is because although ST achieved higher eradication rates than TT it did not reach optimal results in previous studies.23 The present nationwide multicenter study examined whether ST could replace TT as first-line therapy in Korea.

In the PP population, ST achieved eradication rates of 88.8% compared to 76.9% for TT. The absolute risk reduction was 12.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.7 to 18.2) and the number needed to treat was 9 (95% CI, 5.5 to 18.2). These results indicate that ST can replace TT as first-line therapy in Korea. Another concern of ST is the development of antibiotic resistance and the choice of the second-line regimens after failure of ST. Several studies from Europe reported levofloxacin containing triple regimens to be effective as a second-line treatment.27–30 However, fluoroquinolone resistance is reported to be as high as 22.3% to 34.6% in Korea.22,25 Moxifloxacin containing TT following failed first-line ST achieved disappointing eradication rates of 60.4% and 70.7% for ITT and PP populations in Korea.31 Bismuth-based quadruple therapy (BQT) may be an alternative to levofloxacin-based regimens after failed ST. However, BQT should be used for 14 days after failed ST, since metronidazole resistance is suspected in these patients.32 Future studies regarding the optimal second line regimen after failure of ST may be needed before ST can be regarded as first line therapy.

TT is no longer effective in many parts of the world due to increasing clarithromycin resistance and has been deemed as an unethical comparator in clinical trials.12,33 However, a 7-day TT regimen is the only regimen reimbursed by the NHIS and is the most prescribed eradication regimen in Korea. A recent Korean study reported final PP eradication rates of TT to be 98.4% after second-line treatment and 99% after third-line treatment.34 Although TT regimens may not achieve adequate eradication rates as first-line therapies, H. pylori infection was eradicated in most patients following second-line and third-line treatment. Non-BQT such as ST and concomitant therapy may achieve higher eradication rates compared to TT as first-line therapy. However, it is doubtful that the ultimate eradication rates of these regimens will surpass that of TT. Currently most studies regarding first line therapy focus on the efficacy of a regimen as initial treatment. However, we believe that the cumulative eradication rates of a treatment are equally important. The use of non-BQT would expose patients to increased antibiotics which may result in increased antibiotic resistance after treatment. For these reasons, TT may be considered as a first-line regimen for H. pylori infection in Korea.

The main limitation of our study was the lack of evaluation of antibiotic resistance in the patients. However, antibiotic resistance testing is rarely performed before prescribing first-line regimens. So, the study mimics routine clinical practice. As mentioned above, 7-day TT is the most prescribe regimen in Korea and the only regimen reimbursed by the NHIS. Therefore, we chose this regimen as the comparator to ST; thus the duration of TT was shorter than ST. A recent meta-analysis reported that ST was superior to 7-day TT but was not significantly better than 14-day TT.35 Results of our study may have been different if the duration of TT was increased. Finally, the PPIs that were used in our study varied and this may have affected the eradication rates. We were not able to unify the PPIs because different institutions participated in our study. However, the efficacy of different PPIs for eradication have been reported to be similar in Korea and we believe the different PPIs would have a minimal effect on the eradication rates.36

In conclusion, this nationwide multicenter study suggests that ST achieves higher eradication rates than TT as first-line therapy in Korea. However, the PP eradication rates of the ST regimen was less than 90% and little data exists regarding the optimal treatment regimen after failed ST. Further studies are needed to determine if it is worthwhile to include an additional antibiotic for first line therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study registered in Clinical Research Information Service (KCT0000378) and granted from Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research (2011-01).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastric diseases. BMJ. 1998;316:1507–1510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7143.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Xu L, Shi R, et al. Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a meta-analysis. Digestion. 2011;83:253–260. doi: 10.1159/000280318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malfertheiner P, Sipponen P, Naumann M, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication has the potential to prevent gastric cancer: a state-of-the-art critique. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2100–2115. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan FK, Chung SC, Suen BY, et al. Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low-dose aspirin or naproxen. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:967–973. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chey WD, Wong BC Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coelho LG, León-Barúa R, Quigley EM. Latin-American Consensus Conference on Helicobacter pylori infection: Latin-American National Gastroenterological Societies affiliated with the Inter-American Association of Gastroenterology (AIGE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2688–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Review article: the effectiveness of standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori has not changed over the last decade, but it is not good enough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1255–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143–1153. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;62:3–26. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2013.62.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong EJ, Yun SC, Jung HY, et al. Meta-analysis of first-line triple therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: is it time to change? J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:704–713. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.5.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heo J, Jeon SW. Changes in the eradication rate of conventional triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014;63:141–145. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2014.63.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zullo A, Vaira D, Vakil N, et al. High eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori with a new sequential treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:719–726. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JS, Ji JS, Choi H, Kim JH. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Asians: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–3079. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Xiao SD. Sequential therapy vs. standard triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34:41–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, et al. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS, Kim BW, Ham JH, et al. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Liver. 2013;7:546–551. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.5.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham DY, Lee YC, Wu MS. Rational Helicobacter pylori therapy: evidence-based medicine rather than medicine-based evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:177–186.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An B, Moon BS, Kim H, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains and its effect on H. pylori eradication rates in a single center in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:415–419. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.6.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park CS, Lee SM, Park CH, et al. Pretreatment antimicrobial susceptibility-guided vs. clarithromycin-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in a region with high rates of multiple drug resistance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1595–1602. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gisbert JP, Pérez-Aisa A, Bermejo F, et al. Second-line therapy with levofloxacin after failure of treatment to eradicate helicobacter pylori infection: time trends in a Spanish Multicenter Study of 1000 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:130–135. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318254ebdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Castro-Fernández M, et al. Second-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin after H. pylori treatment failure: a Spanish multicenter study of 300 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manfredi M, Bizzarri B, de’Angelis GL. Helicobacter pylori infection: sequential therapy followed by levofloxacin-containing triple therapy provides a good cumulative eradication rate. Helicobacter. 2012;17:246–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zullo A, De Francesco V, Manes G, Scaccianoce G, Cristofari F, Hassan C. Second-line and rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in clinical practice. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang KK, Lee DH, Oh DH, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with moxifloxacin-containing therapy following failed first-line therapies in South Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6932–6938. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu JY, Liou JM, Graham DY. Evidence-based recommendations for successful Helicobacter pylori treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:21–28. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.859522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham DY, Fischbach LA. Letter: the ethics of using inferior regimens in H. pylori randomised trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:852–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon K, Kim N, Nam RH, et al. Ultimate eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori after first, second, or third-line therapy in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:490–495. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatta L, Vakil N, Vaira D, Scarpignato C. Global eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of sequential therapy. BMJ. 2013;347:f4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keum B, Lee SW, Kim SY, et al. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori eradication rate according to different PPI-based triple therapy: omeprazole, rabeprazole, esomeprazole and lansoprazole. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]