Abstract

Background

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress results from protein misfolding imbalance and has been postulated as a therapeutic strategy. ER stress activates the unfolded protein response which leads to a complex cellular response, including the upregulation of aberrant protein degradation in the ER, with the goal of resolving that stress. O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase (MPG), and Rad51 are DNA damage repair proteins that mediate resistance to temozolomide in glioblastoma. In this work we sought to evaluate whether ER stress-inducing drugs were able to downmodulate DNA damage repair proteins and become candidates to combine with temozolomide.

Methods

MTT assays were performed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the treatments. The expression of proteins was evaluated using western blot and immunofluorescence. In vivo studies were performed using 2 orthotopic glioblastoma models in nude mice to evaluate the efficacy of the treatments. All statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

Treatment of glioblastoma cells with ER stress-inducing drugs leads to downregulation of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51. Inhibition of ER stress through pharmacological treatment resulted in rescue of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 protein levels. Moreover, treatment of glioblastoma cells with salinomycin, an ER stress-inducing drug, and temozolomide resulted in enhanced DNA damage and a synergistic antitumor effect in vitro. Of importance, treatment with salinomycin/temozolomide resulted in a significant antiglioma effect in 2 aggressive orthotopic intracranial brain tumor models.

Conclusions

These findings provide a strong rationale for combining temozolomide with ER stress-inducing drugs as an alternative therapeutic strategy for glioblastoma.

Keywords: DNA damage, ER stress, glioblastoma, salinomycin, temozolomide

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive type of primary brain tumor. The current standard treatment is surgery and concomitant administration of temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy.1 Unfortunately, despite all medical efforts, the median survival time of patients with glioblastoma is only 14.6 months.2 TMZ is a DNA-alkylating agent that inserts methyl groups into guanine and adenine nucleotides.3 It triggers the reparation of DNA orchestrated by O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)4 and DNA base excision repair (BER) led by the enzyme N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase (MPG).5 In the case that the previous mechanisms are not able to repair those alterations, the replication will stall or the replication fork will collapse, resulting in double strand breaks (DSBs). There are several reports that underline the significant role of DSB repair proteins in determining the sensitivity to TMZ in preclinical models, including Rad51. Glioblastoma patients whose MGMT promoter is methylated have a better prognosis than those with a wild-type promoter,6 and the overexpression of MPG induces resistance against TMZ.5 Unfortunately, glioblastoma tumors inexorably recur after treatment with TMZ, suggesting tumor resistance to this drug. Therefore, alternative approaches that overcome this resistance are needed to treat this deadly disease.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress results from protein misfolding imbalance and has been shown to participate in the development of cancer.7 However, it has also opened the door to development of alternative therapeutic strategies. Indeed, ER stress-inducing drugs have been useful in cancers such as myeloma.8 ER stress activates the unfolded protein response (UPR),9,10 which leads to a complex cellular response including the upregulation of aberrant protein degradation in the ER, with the goal of resolving the ER stress.11 A clear example is the ER stress–induced degradation of Rad51, a DNA repair protein that plays a key role in the response to radiotherapy.12 This example suggests that other DNA repair proteins could be modulated by ER stress.

Salinomycin (SLM) was identified from a chemical screening as a promising anticancer agent due to its potent cytotoxic effect against cancer stem cells.13 SLM induces ER stress and, depending on the model, triggers autophagy or apoptosis.14–18

In this work we set out to evaluate whether drugs that induce ER stress could enhance TMZ antitumor effect through inhibition of key DNA repair proteins. Our data showed that treatment with ER stress-inducing drugs such as SLM resulted in the downregulation of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 involved in TMZ resistance. Combination of TMZ with SLM led to enhanced DNA damage and in turn increased cell death. Moreover, the combination of SLM/TMZ resulted in a significant antiglioma effect in vitro and in vivo. This combination provides a strong rationale for developing new therapeutic strategies for glioblastoma patients based on the combination of TMZ with ER stress-inducing drugs.

Methods

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

The adult glioma brain tumor stem cell (BTSC) lines GSC23, GSC11, GSC7-2, GSC2-27, GSC5-22, GSC2, GSC231, GSC7-11, GSC10-6, GSC11-28, GSC229, and U87 MG were kindly provided by Dr Lang (Department of Neurosurgery; MD Anderson Cancer Center). The U87 MG, U373 MG, U251 MG, and T98G cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The pediatric cell line SF188 was kindly provided by Dr Jones (Institute of Cancer Research). BTSCs were cultured as neurospheres. The neurospheres were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's/F12 medium (1:1, vol/vol) supplemented with B27 (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific), basic fibroblast growth factor, and epidermal growth factor (20 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) according to the procedures described elsewhere.19 Attached cell cultures were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's/F12 medium (1:1, vol/vol) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Finally, all the cell lines were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Reagents

Where indicated, cells were treated with SLM, tunicamycin, 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) (Sigma-Aldrich), and TMZ (Department of Pharmacy, University Hospital of Navarra). Each of these reagents was resuspended according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblotting Analysis

After the indicated treatments, total cell proteins were extracted on ice with lysis buffer (1% Tween in phosphate buffered saline) in the presence of freshly added proteases and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method. A total of 40 µg/lane protein extract was separated by Tris/glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Blots were incubated with the following antibodies: P62 (Sigma-Aldrich), binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP), protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), phospho-PERK, MPG, MGMT, phospho–eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), phospho–histone H2A.X, Rad51, mutS homolog (MSH)2, mutL homolog (MLH)1, MSH6 (Cell Signaling Technology), and MGMT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). As housekeeping proteins we used glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Abcam), growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (BD Transduction Laboratories), and α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich). Amersham's enhanced chemiluminescence protocol (PerkinElmer) was used to develop membranes.

X-box Binding Protein 1 Splicing Detection

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol, as described by the manufacturer (Life Technologies). Standard PCR was performed and XBP1u (unspliced) and XBP1s (spliced) transcripts were amplified with Amplitaq gold (Applied Biosystems). Primers were described previously by Mahoney (forward 5′-CCTTGTAGTTGAGAACCAGG-3′, reverse 5′-GGGGCTTGGTATATATGTGG-3′).20 PCR products were separated in a 10% polyacrylamide gel.

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Glioblastoma cells were cultured on glass coverslips and fixed with methanol. Samples were blocked in phosphate buffered saline/fetal bovine serum 10%. Cells were then incubated with antibodies directed against phospho-H2A.X (Abcam), LAMP1 (lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1), and cathepsin B (Merck) for 1 h at room temperature. Afterward, samples were incubated with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 594, monkey anti-rabbit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), immunoglobulin G–fluorescein isothiocyanate, and goat anti-mouse (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The coverslips were mounted with mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories). Finally, the fluorescence signals were visualized and digital images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan 2ie).

Cell Viability Assay

Cell lines were seeded at a density of 5×103 cells per well in a 96-well plate. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were treated with SLM or TMZ at concentrations ranging from 1×10−9M to 1×10−3M. Five days later, cell viability was assessed as previously described21 by MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma-Aldrich). Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated with CalcuSyn software (Biosoft), and the results were graphed with GraphPad Prism software. All of the experiments were performed 3 times, with each treatment administered in quintuplicates.

Animals

Athymic mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories. Mice were maintained at the Centro de Investigación Medica Aplicada (Pamplona) in specific pathogen-free conditions and fed standard laboratory chow. The study was approved by the committee of bioethics of our institution. GSC11 or GSC23 human glioma stem cells (5 × 105 and 2.5 × 105, respectively) were engrafted into the caudate nucleus of athymic mice using a guide-screw system as previously described.22 Mice received 2 intratumoral injections of SLM (0.5 µg/animal) per week in a total of 5 administrations. Temozolomide (7.5 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally during 5 days every 28 days for 2 cycles.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

The paraffin-embedded sections of the mice brains were immunostained for antibodies specific for MGMT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), caspase 3, and pH2A.X (both from Cell Signaling Technology). Anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibody (1:150; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied for 40 min at room temperature followed by peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (40 min, 1:50; Sigma-Aldrich). Five representative images from each section were taken at 400× magnification using the Zeiss Axio Imager M1 microscope. For each photograph, positive nucleated cells were counted by Fiji software V1.48q; results were obtained calculating the positive signal versus the negative signal inside the tissue.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons were made using parametric and nonparametric 2-tailed Student's t-tests with GraphPad Prism software. Survival in different treatment groups was compared using the log-rank test.

Results

Salinomycin Triggers Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Glioblastoma Cell Lines

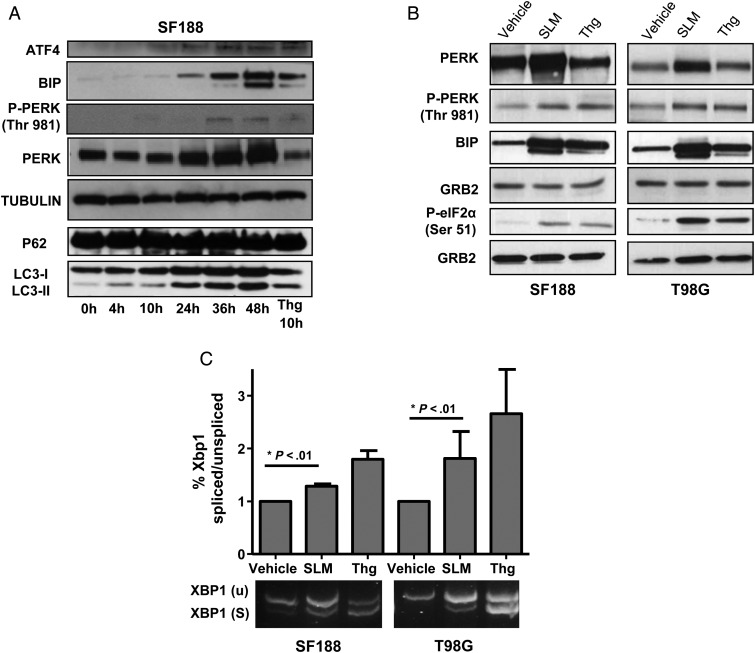

First, to elucidate whether SLM induces ER stress in our model, we performed a time-dependent experiment in SF188 cells treated with SLM. This experiment allowed us to assess the effect of SLM treatment on the kinetics of several ER stress sensors. PERK and BIP levels were increased at 24 h and remained elevated up to 48 h; thapsigargin (Thg)23 was used as positive control. Levels of activating transcription factor 4 were increased upon treatment and up to 48 h, supporting a maintained activation of the PERK-mediated UPR branch (Fig. 1A). In order to assess the possibility that other cellular mechanisms could be activated, we evaluated the autophagy markers LC3 lipidation and p62.24 Interestingly, even though we observed an increase in the lipidation of LC3I to LC3II after SLM treatment that was time dependent, the levels of p62 remained constant, suggesting an aberrant flux of autophagy (Fig. 1A).15

Fig. 1.

SLM induces a potent and maintained UPR in glioma cells. (A) Time-dependent kinetics of the SLM-induced UPR response. SF188 cells were incubated with SLM (0.1 μM) and collected at the indicated times. Cells treated with Thg for 10 h were used as an ER stress positive control. Samples were analyzed by western blot for activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), BIP, pPERK and PERK, p62, and LC3 lipidation. α-Tubulin was used as loading control. (B) SLM and Thg induce the UPR response in glioblastoma cell lines. SF188 or T98G cells were incubated with either SLM (0.1 μM) or Thg (0.1 μM) and collected at 48 h or 4 h, respectively. Samples were analyzed by western blotting for PERK, pPERK, BIP, and phospho-eIF2a. GRB2 was used as the loading control. (C) SF188 or T98G cells were incubated with either SLM (0.1 μM) or Thg (0.1 μM) and collected at 48 h. XBP1 splicing was assessed with conventional PCR. XBP1u (unspliced, 488 bp) and XBP1s (spliced, 418 bp). Shown are representative western blots of 3 independent experiments.

Next, to evaluate the ability of SLM25 and Thg23 to induce ER stress in glioma, we treated SF188, T98G, and U251 MG cell lines with both drugs at dosages where cell viability was over 80% (data not shown) during 48 h. The upregulation of BIP protein levels after treatment with either drug suggested a general UPR activation as a consequence of ER induction. We observed that both agents induced phosphorylation of PERK (Thr981) and eIF2α (Ser51), thus indicating the activation of the PERK signaling pathway,7 which is one of 3 UPR branches.26 Interestingly we observed that PERK protein levels were upregulated in cells treated with SLM compared with Thg-treated cells, perhaps suggesting a more potent cellular response (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S1A). Finally, treatment with either drug resulted in the splicing of the transcription factor XBP1,27 indicating the activation of inositol-requiring enzyme 1,28 another important mediator of the UPR (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S1B).

These results showed that both Thg and SLM were able to induce ER stress and the ensuing UPR response in glioblastoma cell lines. The capacity of SLM to induce a maintained ER stress signal that triggered a strong and maintained UPR response led us to choose this drug over a conventional ER stress-inducing drug such as Thg to perform the mechanistic studies.

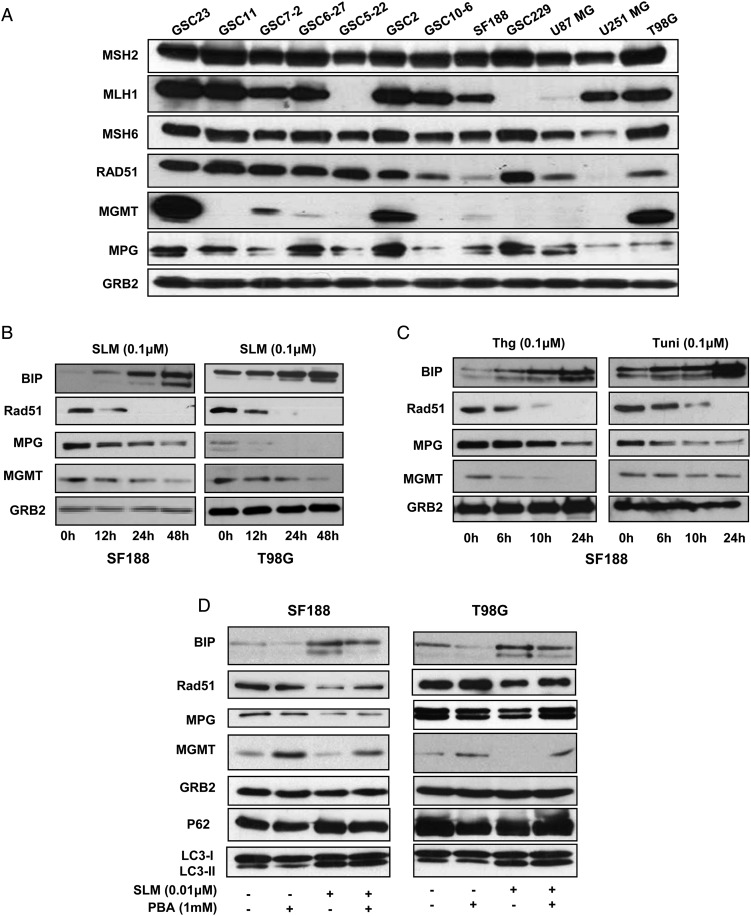

ER Stress Downmodulates MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 in Glioblastoma Cells

First, we screened the status of several proteins involved in the response to TMZ (MGMT, MPG, Rad51, and the mismatch repair [MMR] proteins MSH2, MSH6, and MLH1) in a battery of glioblastoma cell lines (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S1). MPG, Rad51, MSH2, and MSH6 were expressed in the majority of the cell lines evaluated. Since the role of the MMR protein in the TMZ response has been related to mutations of these proteins rather than protein levels, we chose to further investigate the role of ER stress in MGMT, MPG, and Rad51. SLM treatment of glioblastoma cells (SF188, T98G, NSC11, and NSC23) resulted in a pronounced downregulation of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 levels (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S2A),5,6 suggesting that SLM could sensitize cells to TMZ. Since NSC11 does not express MGMT, we did not observe any differences in that cell line in that specific protein (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S2A). Of importance, treatment of glioblastoma cells with the ER stress-inducing drugs Thg and tunicamycin29 resulted in the downregulation of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 proteins (Fig. 2C). These results point toward a common mechanism of protein degradation mediated by ER stress. To uncover a putative direct role of ER stress in the downregulation of MPG and MGMT protein levels, we treated the cells with the ER stress inhibitor PBA.30 Importantly, cotreatment of glioblastoma cells with SLM and PBA led to BIP downregulation and reestablishment of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 protein levels (Fig. 2D). We observed similar results for the SF188 cell line cotreated with Thg and PBA. Addition of PBA rescued the expression of MPG and MGMT proteins (Supplementary Fig. S2B). These data point toward a direct role of ER stress and the UPR response in the downregulation of these protein levels.

Fig. 2.

ER stress downmodulates the DNA repair proteins MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 in glioma cells. (A) The indicated glioma cell lines were collected and MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, Rad51, MGMT, and MPG protein levels were evaluated by western blot. (B) SF188 and T98G cells were incubated with SLM (0.1 μM). Samples were collected at the indicated times, and MPG, MGMT, Rad51, and BIP expression levels were analyzed by western blotting. (C) Treatment of glioma cells with ER stress-inducing drugs results in the downregulation of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51. SF188 or T98G cells were incubated with the ER stress inducers Thg or tunicamycin (Tuni) at the indicated concentrations. The levels of MPG, MGMT, Rad51, and BIP expression were analyzed by western blotting. (D) Treatment of glioma cells with PBA rescues the MGMT and MPG protein levels. SF188 or T98G cells were incubated with SLM, PBA, or both agents. The levels of MPG, MGMT, Rad51, and BIP expression were analyzed by western blotting. In all the panels we used, GRB2 was the loading control. Shown are representative western blots of 3 independent experiments.

Taken together, these results indicated that SLM induces a potent ER stress response followed by the activation of the UPR, leading to the downregulation of key proteins involved in the response to TMZ. Moreover, they suggested that ER stress drugs could be good candidates to combine with TMZ.

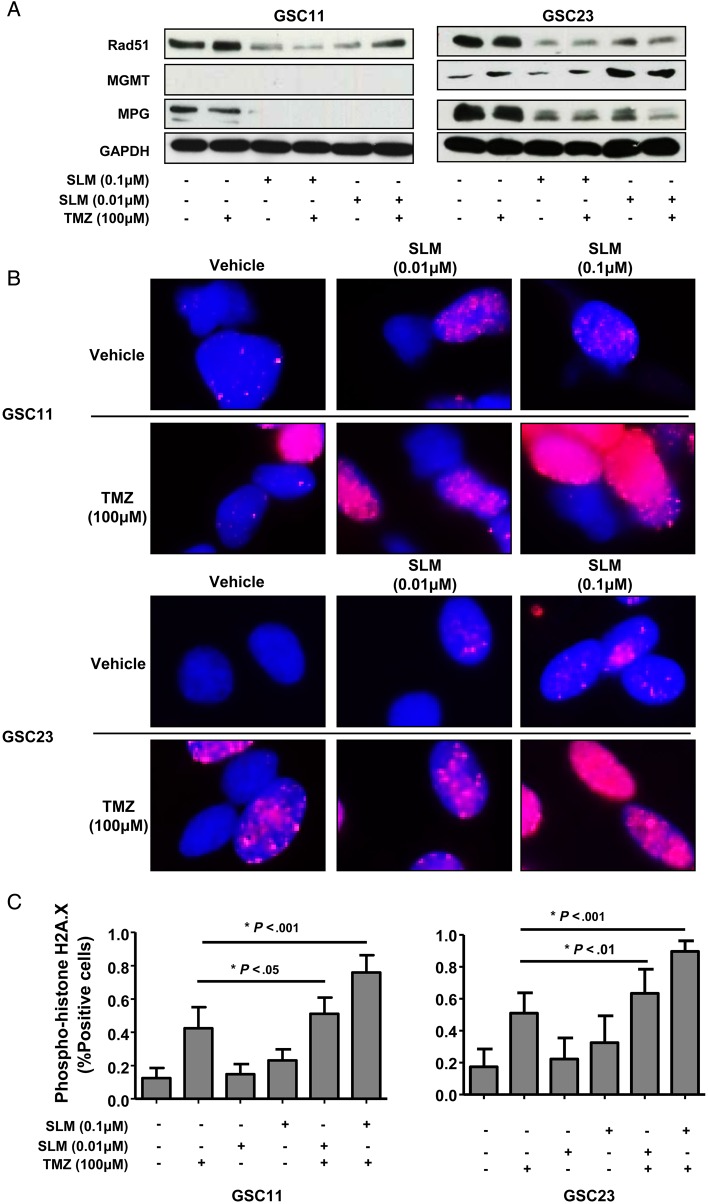

Combination of SLM and TMZ Results in an Increase in DNA Damage

Next, we evaluated the effect of SLM/TMZ combination treatment on the expression of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 in several glioblastoma cell lines (GSC11, GSC23, SF188, and T98G). As expected, combination treatment resulted in the downregulation of the levels of these proteins in glioblastoma cell lines (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S3A). Cells treated with the combination SLM/TMZ displayed elevated levels of pH2A.X, which suggested DNA damage (Supplementary Fig. 3B). In addition, we observed in the combination an aberrant flux of autophagy, as shown by the steady levels of p62 and LC3 lipidation. Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in the amount of cells showing DNA damage compared with that induced by TMZ, as shown by the significant increase in the intensity and number of cells displaying the pH2A.X signal (Fig. 3B and C and Supplementary Fig. S3C).

Fig. 3.

Combination of SLM and TMZ results in an increase in DNA damage. (A) GSC11 and GSC23 cells were incubated with SLM, TMZ, or both at the indicated concentrations. Cells were collected 48 h later, and the levels of Rad51, MPG, and MGMT expression were analyzed by western blot. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as loading control. Shown is a representative western blot of 3 independent experiments. (B) GSC23 and GSC11 cells were incubated at the indicated concentrations. DNA damage was assessed 48 h later using immunofluorescence against pH2A.X. Representative micrographs are shown. (C) Quantification of the DNA damage induced by the combination TMZ/SLM in glioma cell lines. Phospho-H2A.X–positive cells were quantified and presented as the percentage in comparison with cells treated with vehicle only (untreated cells). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

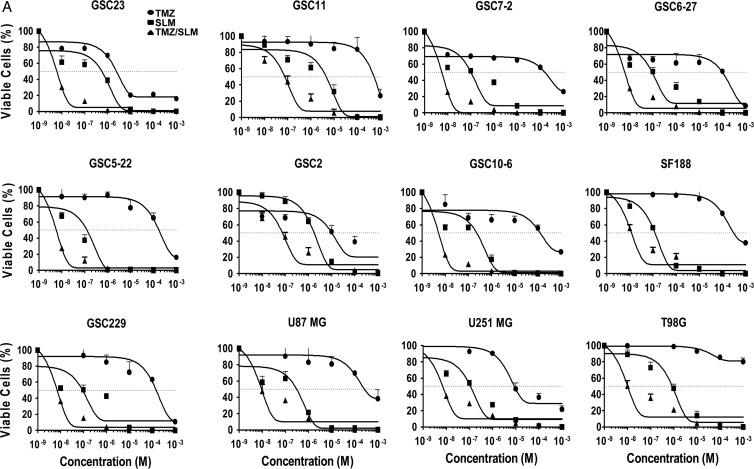

Combination of SLM and TMZ Leads to a Synergistic In vitro Antiglioma Effect

Next, we performed viability assays to evaluate the impact of either treatment on glioblastoma cells. As we expected, the combination SLM/TMZ presents an enhanced antitumor effect compared with either drug alone (Fig. 4A), as shown by their IC50 values (Supplementary Table S1). To confirm the the existence of cell death after the combination treatment in several glioblastoma cell lines, we used trypan blue exclusion as an alternative marker. We observed that the data obtained with the MTT analyses correlated with those results observed with the trypan blue exclusion (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S4A), indicating the validity of the MTT data.

Fig. 4.

Combination of SLM and TMZ induces a synergistic antiglioma effect. (A) The indicated glioma cell lines were incubated with either increasing doses of SLM or TMZ (10−3 M to 10−9 M) or SLM at a dose of 0.1 μM and increasing doses of TMZ (10−3 M to 10−9 M). Seven days after treatment began, cell viability was assessed using MTT assays. The results are expressed as mean values ± SD from 3 independent experiments and are represented as cell viability relative to nontreated cells (=100%).

Overall, combination treatment IC50 values were at least one logarithm lower than SLM alone (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Table S1). To analyze the possible synergistic interactions between SLM and TMZ, we used the isobologram analysis.31 In almost all the tests, the combination index values (Supplementary Table S1) were under 0.7, indicating a clear synergism.

In summary, these data reveal the synergistic antitumor effect of the SLM/TMZ combination. Our data suggest that this therapeutic effect could be mediated by the inhibitory effect of SLM-induced ER stress on key DNA repair proteins, resulting in increased DNA damage due to the incapability of the cells to cope and repair this damage and thereby leading to cell death.

Combination of SLM and TMZ Results in a Significant Antitumoral Effect In vivo

To evaluate the antitumor effect of the combination treatment in vivo, we used an orthotopic intracranial model using the aggressive BTSC lines GSC11 and GSC23. SLM is delivered by Pgp (permeability glycoprotein), a transporter protein overexpressed in the blood–brain barrier, and thus its penetration into the brain is limited.32 To ensure drug delivery and reduce unwanted toxicities, we chose to administer SLM intratumorally. The schedule for SLM (0.02 mg/kg) was one dose every 3 days for a total of 6 administrations; TMZ (7.5 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally 5 days every 21 days.

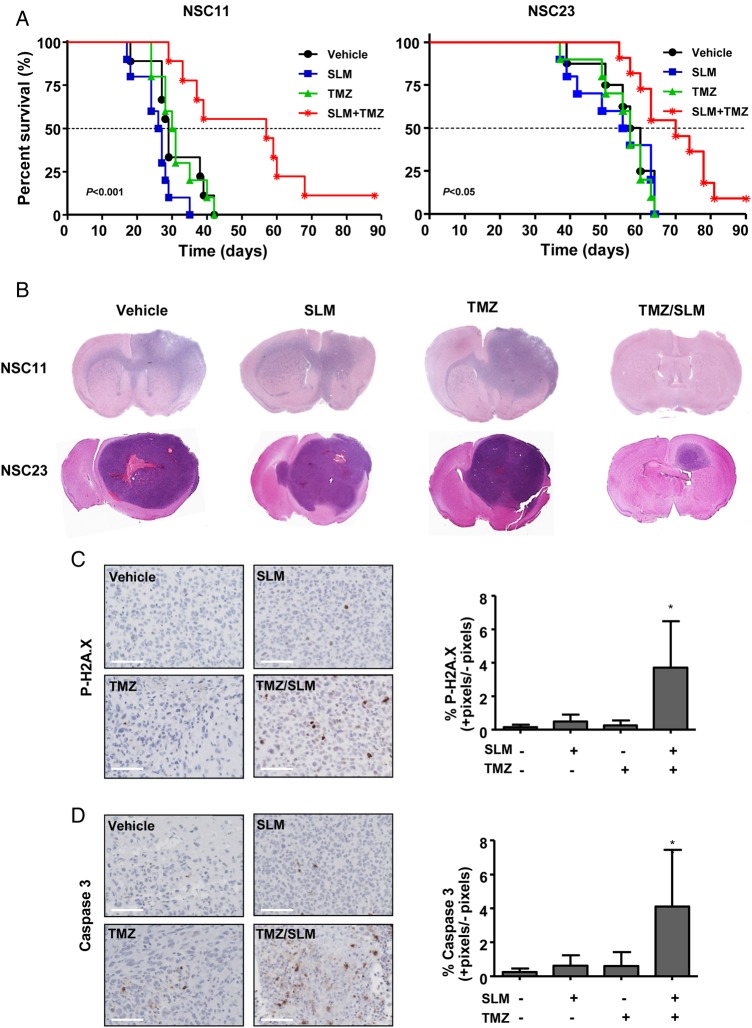

Survival curves showed that neither drug alone provided a survival advantage for these mice. Combination treatment resulted in a significant increase in the overall median survival (P < .001 and P = .03 for GSC11 and GSC23, respectively) and led to long-term survivors (Fig. 5A). Staining with hematoxylin and eosin revealed very aggressive tumors. In the case of GSC11, the tumors infiltrated the brain parenchyma and invaded the contralateral hemisphere. Importantly, the long-term survivor in the combination treatment was tumor free. In regard to GSC23, the tumors were also very aggressive and led to a long-term survivor that, in this case, presented a small tumor (Fig. 5B). With the purpose of studying the molecular mechanisms of the treatment in vivo, we performed a short experiment with GSC11 at 20 days. Animals treated with either SLM or TMZ alone showed positive pH2A.X staining, but the difference was not statistically significant, which suggested limited effectiveness of the drugs themselves. In contrast, their combination induced a significant increase in pH2A.X staining, which indicated increased DNA damage (Fig. 5C). Moreover, combination-treated animals displayed a significant increase in caspase 3 staining compared with either treatment alone, indicating a possible death by apoptosis (Fig. 5D). Finally, our data allowed us to propose a model that summarized our findings (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Combination treatment of SLM and TMZ results in a significant antitumor effect in vivo. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis for overall survival in treated athymic mice bearing intracranial xenograft tumors originated by GSC11 or GSC23 cell lines. The P-values were determined using the log-rank test; the values represent a comparison of survival rates associated with the different treatments given to the mice. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the brains of animals treated with the indicated drugs. (C) Animals were treated with SLM, TMZ, or both and sacrificed 20 d after implantation. Left panel: tissue sections were incubated with anti-pH2A.X antibody (diluted 1:100). Representative photomicrographs are shown. Right panel: quantification of positive cells. Positive signals were counted by Fiji software V1.48q and represented as the percentage in comparison with nontreated animals. Bars represent the mean ± SD of 5 snaps for every brain (N = 3 brains). (D) Animals were treated with SLM, TMZ, or both and sacrificed 20 d after implantation. Left panel: tissue sections were incubated with anti–caspase 3 antibody (diluted 1:100). Representative photomicrographs are shown. Right panel: quantification of positive cells was done as above. Scale bars in (C) and (D) = 100 µM.

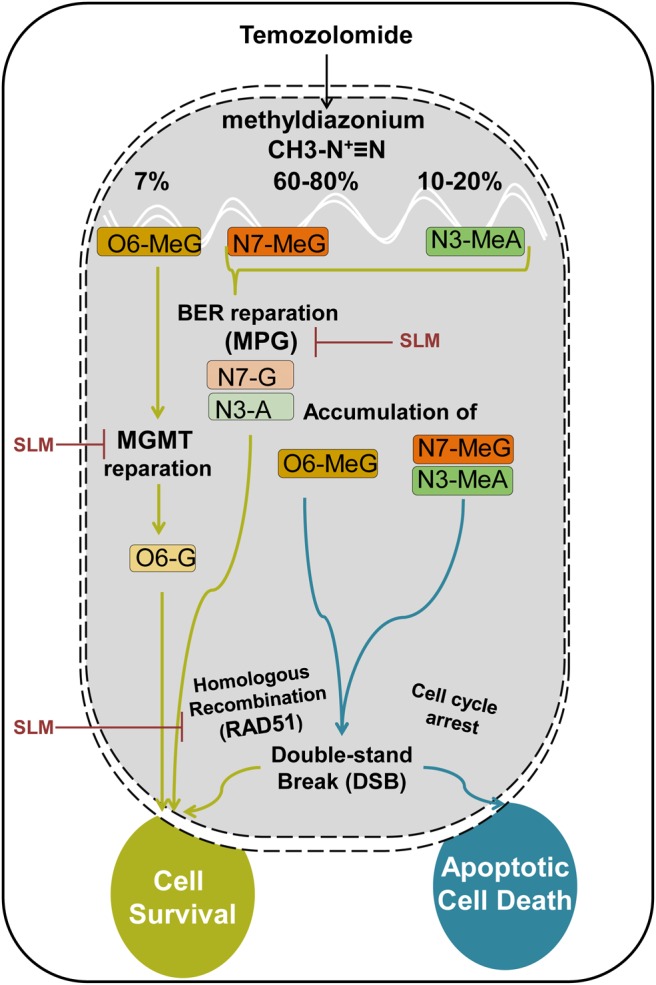

Fig. 6.

Hypothetical proposed model. In physiological conditions, TMZ will be quickly converted into methyldiazonium. This compound has alkylating activity capable of methylating the O6 position of guanine and the N7 position of guanine followed by the N3 position of adenine. Repair mechanisms are different based on the position where the methyl group has been inserted. O6-meG is repaired by the MGMT enzyme. In case the DNA damage exceeds repair capacity of the MGMT, a futile cycle starts, led by the MMR system, which results in DSB in the DNA. If this damage exceeds the capacity of the HR system to repair the cell, it will enter into apoptosis and die. If the methylation is inserted in the N7-meG or N3-meA, the BER system will try to ameliorate this damage and the MPG proteins play an important role here. Again, if the BER system is surpassed, the DNA will accumulate DSBs that if not repaired by the HR system will induce cell death. ER stress-inducing drugs will induce the downregulation of MGMT, MPG (BER system), and Rad51 (HR system), sensitizing the cells to the action of TMZ.

In summary, our data have provided clues regarding the antiglioma efficacy and the molecular underpinning of the SLM/TMZ treatment combination. Moreover, these findings provide a strong rationale for combining TMZ with ER stress-inducing therapies to treat patients with glioblastoma and warrant further studies.

Discussion

In this work we uncover ER stress-inducing drugs as good candidates to combine with TMZ for the treatment of glioblastoma. One consequence of ER stress is the activation of the UPR.9,10 There is much evidence in the literature showing that cancer cells present abnormally elevated UPR levels.33 In the context of glioblastoma, several studies observed augmented BIP levels, a key mediator of the UPR, compared with healthy tissue cells. Moreover, higher BIP expression was correlated with a shorter survival.34–36 Mostly, the data published suggest a protective role of UPR for cancer cells, even though it could induce cell death too if a certain threshold is trespassed.26 An interesting hypothesis proposed by Wang and Kaufman33 is that interfering with basal UPR signaling in cancer cells (either up or down) will result in an antitumor effect. We opted to increase the UPR signaling as a strategy to induce cell death with encouraging results. However, other authors have shown that the inhibition of mitochondrial function and ER stress enhanced TMZ-induced apoptotic cell death in glioma37 with good therapeutic results, at least in vitro. These 2 works exemplified the Wang–Kaufman theory.

One important consequence of the UPR in our model was the downregulation of the DNA repair proteins. DNA damage induced by TMZ results in the activation of a complex DNA reparation mechanism including MGMT, the BER system, MMR, and the homologous recombination (HR) system38 (Fig. 6). We tested MGMT, MPG, and Rad51 as representative executors of the tolerance displayed by glioblastoma cells to TMZ.5,39–41 The fact that cells treated with ER stress-inducing drugs showed reduced or absent expression of these proteins suggested a general mechanism mediated by UPR triggering agents. We could not rule out at this point that other DNA damage proteins, including the MMR proteins, could be affected too.

The consequence of a decrease in MGMT protein levels is the accumulation of methyl groups at the O6-guanine. At the same time, there is an accumulation of methyl groups in N7-guanine and N3-adenine, leading to the accumulation of DSBs38 due to the reduced expression and thus function of MPG protein (included in the BER system38). Altogether the inhibition of MGMT and MPG by ER stress drugs in combination with TMZ action leads to an increment of DSBs in glioblastoma cells. Finally Rad51, a relevant protein implicated in the restoration of DSBs,42 is downregulated by the UPR too, leaving the cells practically crippled to repair the DSB errors, resulting in an increment of cell death.41

The exact contribution of the different repair systems to the resistance of glioblastoma cells to TMZ remains unknown. Genetic mutations found in different members of the MMR system result in altered functionality of this complex. In accordance with this, low levels of MLH1 and PMS2 (postmeiotic segregation increased 2) (proteins of the MMR system38) are associated with TMZ resistance,43 indicating that downregulation of the MMR system could be unfavorable in patients with glioblastoma. Nevertheless, in the context of our work, the observed in vivo and in vitro antitumor effect suggests the high therapeutic benefit of a UPR induction combined with TMZ. On the other hand, it has been published by Agnihotri and colleagues44 how ataxia telangiectasia mutated regulates MPG and promotes therapeutic resistance to alkylating agents in pediatric and adult brain tumors. Using ER stress as a clinical tool could be an attractive strategy, especially in a tumor resistance context mediated by MGMT and the BER system. In this line of thinking, ER stress has been shown to sensitize cancer cells to radiotherapy by downregulating Rad51 levels, a key protein in the HR pathway, through the ubiquitin-proteosome system.12 Whether in our model MGMT and MPG are degraded in the same way needs to be elucidated. In any case, our study reveals possible synergies between ER stress-inducing agents and DNA-damaging drugs.

Even though SLM has shown a formidable cytotoxicity in vitro, unfortunately it presents several therapeutic disadvantages, such as unfavorable blood–brain barrier permeability32 and elevated toxicity (data not shown). The utilization of ER stress-inducing drugs with better pharmacokinetic profiles emerges as an interesting strategy against glioblastoma.

We were surprised to observe that neither treatment alone nor combined with TMZ provided a survival benefit to the animals, especially SLM, which displayed a strong antiglioma effect in vitro. Poor diffusion of this drug or a low concentration leading to a protective UPR could have caused that effect; therefore, additional studies are needed to clarify this point. On the other hand, drug combination exhibited a significant antitumor effect, which supported the idea of the synergistic antitumor effect observed in vitro. SLM could be stripping the cells from the protective effect of MGMT, MPG, and Rad51, thereby sensitizing them to the cytotoxic effect of TMZ and in turn increasing cell death and mediating the antitumor effect that we observed in our model.

Our data have provided clues regarding the antiglioma efficacy and the molecular underpinning of the SLM/TMZ treatment combination. Our findings provide a strong rationale for combining TMZ with ER stress-inducing drugs to treat patients with glioblastoma and warrant further studies.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union (Marie Curie IRG270459 to M.M.A.), the Spanish Ministry of Health (PI10/00399 and PI13/125 to M.M.A.), the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Ramón y Cajal contract RYC-2009-05571 to M.M.A.), the L'Oreal-UNESCO Foundation, the Department of Health of the Government of Navarra, the Basque Foundation for Health Research (BIOEF, BIO13/CI/005), and the CajaNavarra Foundation (to M.M.A.). E.X. is supported by a fellowship from the Credit Andorra Foundation. A.M.A. is supported by a fellowship from Friends of the University of Navarra (ADA). C.J. acknowledges NHS funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden and the ICR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Hess (Department of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) for editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reardon DA, Rich JN, Friedman HS et al. Recent advances in the treatment of malignant astrocytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(8):1253–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Gander M, Leyvraz S et al. Current and future developments in the use of temozolomide for the treatment of brain tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(9):552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ochs K, Kaina B. Apoptosis induced by DNA damage O6-methylguanine is Bcl-2 and caspase-9/3 regulated and Fas/caspase-8 independent. Cancer Res. 2000;60(20):5815–5824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agnihotri S, Gajadhar AS, Ternamian C et al. Alkylpurine-DNA-N-glycosylase confers resistance to temozolomide in xenograft models of glioblastoma multiforme and is associated with poor survival in patients. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):253–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Godard S et al. Clinical trial substantiates the predictive value of O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation in glioblastoma patients treated with temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(6):1871–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke HJ, Chambers JE, Liniker E et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in malignancy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(5):563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincenz L, Jager R, O'Dwyer M et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response: targeting the Achilles heel of multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(6):831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai YC, Weissman AM. The unfolded protein response, degradation from endoplasmic reticulum and cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(7):764–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. That which does not kill me makes me stronger: adapting to chronic ER stress. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(10):469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonifacino JS, Weissman AM. Ubiquitin and the control of protein fate in the secretory and endocytic pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:19–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamori T, Meike S, Nagane M et al. ER stress suppresses DNA double-strand break repair and sensitizes tumor cells to ionizing radiation by stimulating proteasomal degradation of Rad51. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(20):3348–3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta PB, Onder TT, Jiang G et al. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell. 2009;138(4):645–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li T, Su L, Zhong N et al. Salinomycin induces cell death with autophagy through activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human cancer cells. Autophagy. 2013;9(7):1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue W, Hamai A, Tonelli G et al. Inhibition of the autophagic flux by salinomycin in breast cancer stem-like/progenitor cells interferes with their maintenance. Autophagy. 2013;9(5):714–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JH, Yoo HI, Kang HS et al. Salinomycin sensitizes antimitotic drugs-treated cancer cells by increasing apoptosis via the prevention of G2 arrest. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418(1):98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boehmerle W, Endres M. Salinomycin induces calpain and cytochrome c–mediated neuronal cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Li P, Xue X et al. Salinomycin induces apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant colorectal cancer cells by accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Toxicol Lett. 2013;222(2):139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):7011–7021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahoney DJ, Lefebvre C, Allan K et al. Virus-tumor interactome screen reveals ER stress response can reprogram resistant cancers for oncolytic virus-triggered caspase-2 cell death. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(4):443–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso MM, Jiang H, Yokoyama T et al. Delta-24-RGD in combination with RAD001 induces enhanced anti-glioma effect via autophagic cell death. Mol Ther. 2008;16(3):487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lal S, Lacroix M, Tofilon P et al. An implantable guide-screw system for brain tumor studies in small animals. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(2):326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thastrup O, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK et al. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2(+)-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(7):2466–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8(4):445–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitani M, Yamanishi T, Miyazaki Y et al. Salinomycin effects on mitochondrial ion translocation and respiration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9(4):655–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334(6059):1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oslowski CM, Urano F. Measuring ER stress and the unfolded protein response using mammalian tissue culture system. Methods Enzymol. 2011;490:71–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aragon T, van Anken E, Pincus D et al. Messenger RNA targeting to endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling sites. Nature. 2009;457(7230):736–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torres-Quiroz F, Garcia-Marques S, Coria R et al. The activity of yeast Hog1 MAPK is required during endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by tunicamycin exposure. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(26):20088–20096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolb PS, Ayaub EA, Zhou W et al. The therapeutic effects of 4-phenylbutyric acid in maintaining proteostasis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;61:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lagas JS, Sparidans RW, van Waterschoot RA et al. P-glycoprotein limits oral availability, brain penetration, and toxicity of an anionic drug, the antibiotic salinomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(3):1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(9):581–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyrko P, Schonthal AH, Hofman FM et al. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP as a novel target for increasing chemosensitivity in malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9809–9816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang LH, Yang XL, Zhang X et al. Association of elevated GRP78 expression with increased astrocytoma malignancy via Akt and ERK pathways. Brain Res. 2011;1371:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee HK, Xiang C, Cazacu S et al. GRP78 is overexpressed in glioblastomas and regulates glioma cell growth and apoptosis. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10(3):236–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CJ, Lee CC, Shih YL et al. Inhibition of mitochondria- and endoplasmic reticulum stress–mediated autophagy augments temozolomide-induced apoptosis in glioma cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshimoto K, Mizoguchi M, Hata N et al. Complex DNA repair pathways as possible therapeutic targets to overcome temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2012;2:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Han EK, Anderson M et al. Acquired resistance to combination treatment with temozolomide and ABT-888 is mediated by both base excision repair and homologous recombination DNA repair pathways. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(10):1686–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Short SC, Giampieri S, Worku M et al. Rad51 inhibition is an effective means of targeting DNA repair in glioma models and CD133+ tumor-derived cells. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(5):487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costanzo V. Brca2, Rad51 and Mre11: performing balancing acts on replication forks. DNA Repair (Amst). 2011;10(10):1060–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shinsato Y, Furukawa T, Yunoue S et al. Reduction of MLH1 and PMS2 confers temozolomide resistance and is associated with recurrence of glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2013;4(12):2261–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agnihotri S, Burrell K, Buczkowicz P et al. ATM regulates 3-methylpurine-DNA glycosylase and promotes therapeutic resistance to alkylating agents. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(10):1198–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.