Abstract

From the mid-1950s through the mid1980s, migration between Mexico and the United States constituted a stable system whose contours were shaped by social and economic conditions well-theorized by prevailing models of migration. It evolved as a mostly circular movement of male workers going to a handful of U.S. states in response to changing conditions of labor supply and demand north and south of the border, relative wages prevailing in each nation, market failures and structural economic changes in Mexico, and the expansion of migrant networks following processes specified by neoclassical economics, segmented labor market theory, the new economics of labor migration, social capital theory, world systems theory, and theoretical models of state behavior. After 1986, however, the migration system was radically transformed, with the net rate of migration increasing sharply as movement shifted from a circular flow of male workers going a limited set of destinations to a nationwide population of settled families. This transformation stemmed from a dynamic process that occurred in the public arena to bring about an unprecedented militarization of the Mexico-U.S. border, and not because of shifts in social, economic, or political factors specified in prevailing theories. In this paper I draw on earlier work to describe that dynamic process and demonstrate its consequences, underscoring the need for greater theoretical attention to the self-interested actions of politicians, pundits, and bureaucrats who benefit from the social construction and political manufacture of immigration crises when none really exist.

In the 1990s, at the behest of Massimo Livi-Bacci, then President of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, I agreed to chair an interdisciplinary, international committee of migration scholars for the IUSSP. The committee’s charge was to develop a unified theoretical framework for the study of international migration by identifying the key propositions derived from prevailing migration theories and then to assess them against empirical evidence from international migration systems around the world. The ultimate goal was to encourage researchers from different nations and disciplines to speak a common theoretical language, thereby enabling them to test hypotheses of mutual interest using comparable data and methods. The committee consisted of Joaquin Arango, a sociologist from Spain who was familiar with migration in Europe; Graeme Hugo, a geographer from Australia with knowledge of Asia and the Pacific; Ali Kouaouci, a social demographer from Algeria who covered Africa and the Middle East; Adela Pellegrino, a historical demographer from Uruguay with expertise in Latin America; and J. Edward Taylor an economist from the United States who, like me, did field research in Mexico and knew the North American migration system well, but also had published widely on issues of migration and development around the world..

As professional committees go, the IUSSP Committee on South-North Migration was rather productive. During 1991 and 1992 we met twice each year in Liege, Belgium (where the IUSSP was then headquartered). Each committee member presented the theoretical models he or she thought merited serious consideration and identified an empirical literature fir the committee to review. We then assigned tasks of reading, reviewing, and writing to committee members and began to publish our findings in 1993, when we offered an initial survey of the panorama of theories prevailing across disciplines circa 1990 (Massey et al. 1993). This article was followed a year later by an assessment of how the theories performed when applied to explain patterns and processes of international migration within North America, the region where empirical research was then most abundant (Massey et al. 1994).

While other committee members worked to assemble citations and sources and write chapters for the final book, Edward Taylor took the lead in putting together two additional articles reviewing theory and research on international migration and economic development, one focused on work at the community level (Taylor et al. 1996a) and the other focused at the national level (Taylor et al. 1996b), both of which later became book chapters. Writing on the book was completed in late 1997 and it was published in 1998 as Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium (Massey et al. 1998).

In those days, no self-respecting IUSSP committee could fail to organize an international workshop of some sort, so the final act of the committee was to issue a call for papers and organize a small conference to present research findings relevant to the committee’s integrated theoretical vision. The workshop convened in May of 1997 in Barcelona, Spain, and ultimately produced the edited volume International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Global Market (Massey and Taylor 2004). In this book, a diverse set of authors explored the contours of migration patterns and policies in the globalizing economy of the late 20th century.

In retrospect, I think the committee substantially met its goals and fulfilled its charge quite well. The original theoretical review article (Massey et al. 1993), as well as the more comprehensive book (Massey et al. 1998) have found their way into syllabi and curricula throughout the world. As a result, migration researchers today generally appear to be familiar with the leading theoretical frameworks coming from different disciplines and are increasingly addressing questions of common interest using similar methodologies. As the book was in production, however, I personally came to believe that the committee had overlooked a key actor in the process of international migration: namely, the state—the organ responsible for the formulation and implementation of immigration policy.

A key difference between the first round of globalization (between 1820 and 1920) and the second round (1970-present) was the degree of involvement of national governments in managing international population flows (Williamson 2004). Prior to the First World War, a system of passports and visas did not exist and no country imposed quantitative limits on the entry of immigrants. Today, of course, passports are required for all international travel outside of migration unions such as the Schengen Zone, visas are required for most passports around the world, and all countries impose both quantitative and qualitative limitations on entry for permanent settlement. Thus nation states today necessarily play a role in determining the number and characteristics of immigrants flowing from country to country, apart from the social and economic factors covered in the theories reviewed by the IUSSP Committee.

Given this realization, I took it upon myself to undertake a review of theories and research on the role of states in formulating immigration policies and the likely effects of their attempts at implementation. The review, which I viewed as a compliment to the committee’s book and papers, was published as an article in the Population and Development Review (Massey 1999). It identified three broad sets of variables as key determinants of immigration policy formulation: macroeconomic conditions such as employment and wages, the relative size of the immigrant flow, and the ideological context of the time, with the actual effect of these policies being contingent on the capacity and efficacy of the state seeking to implement them (Massey 1999).

THEORIZING INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION

The end result of all of the foregoing work was a comprehensive framework that theorized five features of international migration (Massey 2013): (1) the structural forces in sending nations that create a mobile population prone to migration; (2) the structural forces in receiving nations that generate a persistent demand for migrant workers; (3) the motivations of the people who respond to these structural forces by moving across borders; (4) the social structures and organizations that arise in the course of globalization to perpetuate flows of people over time and across space; (5) and the policies that governments implement in response to these forces and how they function in practice to shape the numbers and characteristics of the migrants who enter and exit a country.

The principal frameworks theorizing the creation of migrant-prone populations in sending countries are world systems theory in sociology (Portes and Walton 1981; Sassen 1988) and institutional theory in economics (North 1990). Both perspectives posit that migrants originate in the structural transformation of societies brought about by the creation and expansion of markets in the course of economic development (Massey 1988). The transition from a command or subsistence economy to a market system typically entails a massive restructuring of social institutions and cultural practices, and in the course of these transformations people are displaced from traditional livelihoods in subsistence farming (as peasant agriculture gives way to commercialized farming) and state enterprises (as state-dominated sectors are privatized in former command economies).

The generation of a persistent demand for low-wage immigrant workers in post-industrial societies is theorized under the rubric of segmented labor market theory. Originally developed by Piore (1979) as dual labor market theory, this perspective traces the persistent demand for immigrant workers to the duality between labor (a variable factor of production) and capital (a fixed factor of production), which yields a capital-intensive sector to satisfy constant demand and a labor-intensive sector to accommodate variable demand associated with economic cycles that fluctuate over time. The resulting segmented labor market structure is reinforced by hierarchically-structured occupational structures, which create motivational problems at the bottom of the pyramid (where people are unwilling to work hard or remain long in low status jobs they can’t escape) and structural inflation (where raising wages at the bottom generates upward pressures on wages throughout the job hierarchy). Under these circumstances, employers have a hard time recruiting and keeping native workers at profitable wages and seek foreign laborers instead, either prevailing upon governments to establish formal guest worker programs or engaging in private recruitment efforts. Portes and Bach (1985) later augmented Piore’s dual labor market theory by pointing out that ethnic communities under certain circumstances can generate their own demand for immigrants and may, if the right conditions prevail, become vertically integrated in ways that generate a long-term demand for additional immigrant workers, thereby creating ethnic enclaves as a third potential labor market sector..

The motives of those who respond to the foregoing structural forces are theorized both by neoclassical economics and the new economics of labor migration. The former holds that people move to maximize lifetime earnings. Individuals assess the money they can expect to earn by working locally and compare it to what they anticipate earning at various destinations, both domestic and international. Then they project future income streams at different locations over their working lives (subject to a time-varying discount factor typically modeled as a negative exponential) and subtract out the expected costs of migration, yielding an estimate of expected net lifetime earnings at different destinations. In theory, people migrate to the location offers the highest lifetime returns for their labor so that in the aggregate labor flows from low- to high-wage areas until an equilibrium is reached (Todaro and Maruszko 1986).

Rather than maximizing income, the new economics of labor migration argues that people use international labor migration to manage economic risk and overcome missing, failed, or inefficient markets for capital, credit, and insurance at places of origin (Stark 1991). In contrast to the permanent migration hypothesized by neoclassical economics, the new economic paradigm predicts circular movement and the repatriation of earnings in the form of remittances or savings. It also recognizes that people are embedded with households and therefore may engage in collective rather than individual decision-making. Rather than moving abroad permanently, people move abroad temporarily to diversify household incomes and accumulate cash they cannot save or borrow at home, and then return home with the means to solve specific household economic problems originally prompted them to move.

Although neoclassical theory is generally thought to predict permanent migration, Dustmann and Görlach (2015) have recently shown that the neoclassical model of Todaro and Maruszko (1987) is but a special case of a more general model of migrant decision-making. In their theoretical formulation, wage differentials constitute the primary determinant of migration only under certain restrictive conditions, such as when preferences for consumption in both countries are identical; when national currencies do not differ in purchasing power; and when there is no skill accumulation abroad. They demonstrate that departures from these conditions lead to a variety of theoretically expected rationales for workers to prefer temporary over permanent international migration even under neoclassical assumptions.

Globalization inevitably entails the movement of people across international borders, either as bearers of labor or human capital, and the principal model articulated to describe the formation and elaboration of social structures during the course of migration itself is social capital theory (Massey et al. 1998). The first migrants to move abroad have no social ties to draw upon for assistance, and for them migration is costly, risky, and daunting, especially if it involves entering another country without documents. As out-migration progresses, however, a social infrastructure arises and often develops a powerful momentum to yield a self-perpetuating process known as cumulative causation (Massey 1990; Massey and Zenteno 1999).

Pioneer migrants are inevitably linked to non-migrants in their home communities through networks of reciprocal obligation based on shared understandings of kinship and friendship and non-migrants draw upon network ties to facilitate departure, migration, entry, employment, housing, and mobility at points of foreign destination, substantially reducing the costs and risks of international movement. Once the number of network connections in an origin area reaches a critical level, migration becomes self-perpetuating because migration itself creates the social structure necessary to sustain it, especially in rural areas where interpersonal networks are dense and social ties strong (Flores-Yeffal 2012). The cumulative causation of migration through network expansion tends to be much weaker or inoperative in urban settings (Fussell and Massey 2004).

According to the theory of the state outlined in my review, policies affecting immigration grow out of a political process in which competing interests interact within bureaucratic, legislative, judicial, and public arenas to influence the flow and characteristics of immigrants (Massey 1999). In general, this competition of interests is posited to generate permissive immigration policies during periods of economic expansion and restrictive policies during periods of contraction. In most theoretical renderings, the critical actors are workers and employers, with politicians and government actors playing a mediating role in balancing the competing interests. During boom times unemployment rates fall and wages rise and employers lobby the government for more migrant workers, whereas during times of bust workers press demands through their legislators to restrict immigration; and public officials are basically hypothesized to alternate back and forth to satisfy the most vocal and demanding constituency at any point in time.

In addition to economic conditions, immigration policy is sensitive to the relative number of immigrants involved, with the politics of immigration becoming more conflictive and tending toward restriction as the volume of immigration rises (Massey 1999). Immigration policies are also associated with broader ideological currents in society, tending toward restriction during periods of social conformity and conservatism and tilting toward expansion during periods of openness and liberalism. Policies are also shaped necessarily by geopolitical considerations, especially those dealing with refugees and asylum seekers.

Finally, whatever the direction specific national policies ultimately take—restrictive or permissive—an additional consideration is the ability of the state to enforce them. In my paper, I argued that state capacity varies along a continuum from low to high depending on the efficiency of the nation’s bureaucracy, the strength of constitutionally embedded rights, the degree of judicial independence in enforcing those rates, and the relative demand for entry the country and the strength of its tradition of immigration. Thus the ability to enforce policy is strong in Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, which do not have a tradition of immigration and are dominated by absolute monarchies that offer no constitutional rights that are administered by rigid, citizen-run bureaucracies that answer to no independent judicial authority. In contrast the ability to enforce policy is more limited in liberal democracies which have constitutional rights, independent judiciaries, competitive elections, and diffuse and inefficient bureaucracies, especially in nations such as the United States which have a strong historical tradition of immigration and immigrant rights, as we shall see.

THE MISSING ELEMENT AND MEXICO-U.S. MIGRATION

Since 1982 I have worked with my colleague Jorge Durand of the University of Guadalajara to build the Mexican Migration Project (MMP), which annually gathers data on international migration from representative samples of communities located throughout Mexico, along with network samples of branch communities in the United States (see Durand and Massey 2004). Although small migration streams to Canada have recently emerged (Massey and Brown 2011), the overwhelming majority Mexican migrants go to the United States as part of a tradition that dates back to the turn of the 20th Century (Cardoso 1980; Massey et al. 1987; Durand and Massey 1995).

Over the years, we have analyzed these data drawing heavily on the composite framework described above to study the dynamics of Mexico-U.S. migration, seeking to connect variation in migration probabilities to variations over time in wage rates, labor demand, interest rates, and structural economic changes, changing stocks of human and social capital on both sides of the border, and policy-relevant variables such as U.S. enforcement efforts and access to legal visas (Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey, Durand, and Pren 2014). The accumulated research literature based on MMP data suggests that all of the theoretical perspectives contribute something to the understanding of Mexico-U.S. migration, though the relative importance of different theoretical perspectives appears to vary across time (Garip 2012) and from place to place (Durand and Massey 2003).

From 1942 to 1965 Mexican migration generally behaved as expected under prevailing theories of international migration, being initiated by a government sponsored labor recruitment program (segmented labor market theory), growing as lawmakers increased access to temporary workers at the behest of employers (state theory), expanding also because of the elaboration of migrant networks (social capital theory), and fluctuating with respect to changing conditions of labor supply and demand on both sides of the border (neoclassical economics) as well geographic and temporal variation in access to markets for capital, credit and insurance (the new economics of labor migration) and the structural transformation of the Mexican economy under neoliberalism (world systems theory). During this time, migration was overwhelmingly circular, with male migrants moving back and forth to solve economic problems at home (in keeping with predictions derived from the new economics of labor migration and the recent reformulation of neoclassical economics).

In 1965, however, U.S. immigration law was reformed and the guest worker program was eliminated, in both cases for ideological reasons (consistent with state theory). In the context of a burgeoning civil rights movement the guest worker program came to be seen as racially discriminatory and exploitive while immigration quotas imposed in the 1920s were perceived as intolerably racist. The net effect of both actions was to reduce opportunities for legal entry from Mexico quite dramatically. As a result, after 1965 migration occurred under undocumented auspices given the existence of well-developed networks connecting migrants to employers (social capital theory), the continuation of strong demand in North American labor markets (segmented labor market theory), the persistence of a large binational wage gap (neoclassical economics), and the growing integration of the Mexican and U.S. economies (world systems theory).

From 1965 through 1985, migration nonetheless remained overwhelming circular, with male migrants moving back and forth to employers in traditional destination areas in tandem with fluctuating economic circumstances north and south of the border, repatriating earnings to family members at home, and participating well-developed migrant networks. Beginning in 1986 and accelerating through the 1990s, however, this stable pattern of migration shifted markedly. Circulation turned to settlement as rates of return migration plummeted, migrants began flowing to new rather than traditional destination areas, and as men stayed away longer women and children increasingly joined them north of the border. In short, between 1986 and 2006 Mexican migration shifted from a circular flow of male workers going to a few states into a rapidly growing settled population of families in 50 states.

However, this shift did not occur because of changes in labor demand, relative wages, cross-border integration, migrant networks, or because of a changed ideology or a new political balance between employers and works. Rather the driving force was the behavior of self- interested bureaucrats, politicians, and pundits who sought to mobilize political and material resources for their own benefit irrespective of what effects their actions had on immigration itself. The end result was the creation of self-perpetuating cycle of rising enforcement and increased border apprehensions that resulted in the militarization of the border in a way that was largely disconnected from the processes hypothesized by prevailing theories of international migration.

The actions taken by actors in the federal bureaucracy did not emerge in response to the competing demands of workers, employers, and ordinary citizens, so much as the desire to accumulate power and resources. Although the self-interested actions of politicians and bureaucrats have been described and documented historically (see Calavita 1992), heretofore they have not been properly theorized. The key to understanding opportunistic actions taken by actors in and outside of government lies in the transformed context of decision-making before and after 1965. Although little had changed in practical terms before and after this date (roughly the same number of migrants were migrating from the same regions of Mexico to the same places in the United States), the situation had changed dramatically in symbolic terms for after 1965 the vast majority of Mexican migrants were "illegal" and thus by definition "criminals" and "lawbreakers."

The rise of illegal migration created an opening for political entrepreneurs to cultivate a new politics of fear, framing Latino immigration as a grave threat to the nation (Santa Anna 2002; Abrajano and Hajnal 2015), creating a new meme in American public discourse that Chavez (2008) has called the "Latino Threat Narrative" in the U.S. media. His coding of cover stories in leading weekly news magazines showed that negative depictions of immigrants and immigration increased over time (Chavez 2001); and Massey and Pren (2012a) likewise found that newspaper mentions of Mexican immigration as a crisis, flood, or invasion rose in tandem with border apprehensions from 1965 to 1979, pushing public opinion in a more conservative and anti-immigrant direction and creating pressure for ever more restrictive immigration and border policies (Massey and Pren 2012b; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina 2012).

By framing them as aliens, lawbreakers, and criminals, the Latino Threat Narrative distinguished undocumented migrants from mainstream Americans by a well-defined social boundary. Fear, of course, is a well-established tool for political mobilization and resource acquisition (Robin 2006; Gardner 2008) and across history it has proved difficult for humans to resist the temptation to cultivate fear and loathing of outsiders in order to achieve self-serving goals. In the United States, three prominent categories of social actors succumbed to the temptation for “othering” in response to rising illegal migration after 1965: bureaucrats, politicians, and pundits.

The bureaucratic charge was led in 1976 by the Commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, Leonard F. Chapman, who published an article in Reader's Digest entitled "Illegal Aliens: Time to Call a Halt!", warning Americans that a new "silent invasion" was threatening the nation:

When I became commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in 1973, we were out-manned, under-budgeted, and confronted by a growing, silent invasion of illegal aliens. Despite our best efforts, the problem---critical then---now threatens to become a national disaster. Last year, an independent study commissioned by the INS estimated that there are 8 million illegal aliens in the United States. At least 250,000 to 500,000 more arrive each year. Together they are milking the U.S. taxpayer of $13 billion annually by taking away jobs from legal residents and forcing them into unemployment; by illegally acquiring welfare benefits and public services; by avoiding taxes (Chapman 1976: 188–189).

Chapman went on to argue for the passage of restrictive immigration legislation in Congress that was "desperately needed to help us bring the illegal alien threat under control" because "the understaffed [Immigration] Service vitally needs some budget increases." Although the numbers were never justified and no "independent study" was ever released, they were useful in defining illegal migrants as a concrete threat ("taking away jobs and milking the taxpayer") and morally suspect (welfare abusers and tax cheats), following the classic logic of intergroup threat theory (Stephan and Renfro 2002; Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison 2015).

The most prominent politician contributing to the Latino Threat Narrative was President Ronald Reagan, who in 1985 declared undocumented migration to be "a threat to national security" and warned that "terrorists and subversives [are] just two days driving time from [the border crossing at] Harlingen, Texas" and that Communist agents were ready "to feed on the anger and frustration of recent Central and South American immigrants who will not realize their own version of the American dream" (Massey, Durand, and Malone 2002:87). More recently, Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County, Arizona became his state’s most population politician by was taking forceful action "on illegal immigration, drugs and everything else that threatens America" (Arpaio and Sherman 2008).

Pundits made their contributions to the Latino Threat Narrative in order to sell books and boost media ratings. On his television program, Lou Dobbs (2006) nightly told Americans that the "invasion of illegal aliens" was part of a broader "war on the middle class" hatched by liberal elites. Political commentator Patrick Buchanan (2007), meanwhile, alleged that illegal migration was part of an "Aztlan Plot" hatched by Mexicans to recapture lands lost in 1848 while academic pundit and policy advisor Samuel Huntington (2004) portrayed Latino immigrants as a threat to America's national identity, warning that "the persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages…. The United States ignores this challenge at its peril."

None of the foregoing pronouncements was based on any substantive understanding of the realities of undocumented migration. At best they were distortions designed to cultivate fear among native born white Americans for self-interested purposes of boosting ratings, selling air-time, and hawking books. As a result, even though the actual flow of undocumented migrants had stabilized by the late 1970s and was no longer rising (Massey and Pren 2012b), the Latino Threat Narrative kept gaining traction to generate a rising moral panic about illegal aliens that produced a self-perpetuating increase in resources dedicated to border enforcement (Flores-Yeffal, Vidales, and Plemons 2011). Over time, as more Border Patrol Officers were hired and given more equipment and resources, they naturally apprehended more migrants and the rising number of border apprehensions was then taken as self-evident proof of the ongoing "alien invasion," justifying agency requests for still more enforcement resources and ultimately yielding a self-feeding cycle of enforcement, apprehensions, more enforcement, more apprehensions, and still more enforcement.

CONSEQUENCES OF THE LATINO THREAT NARRATIVE

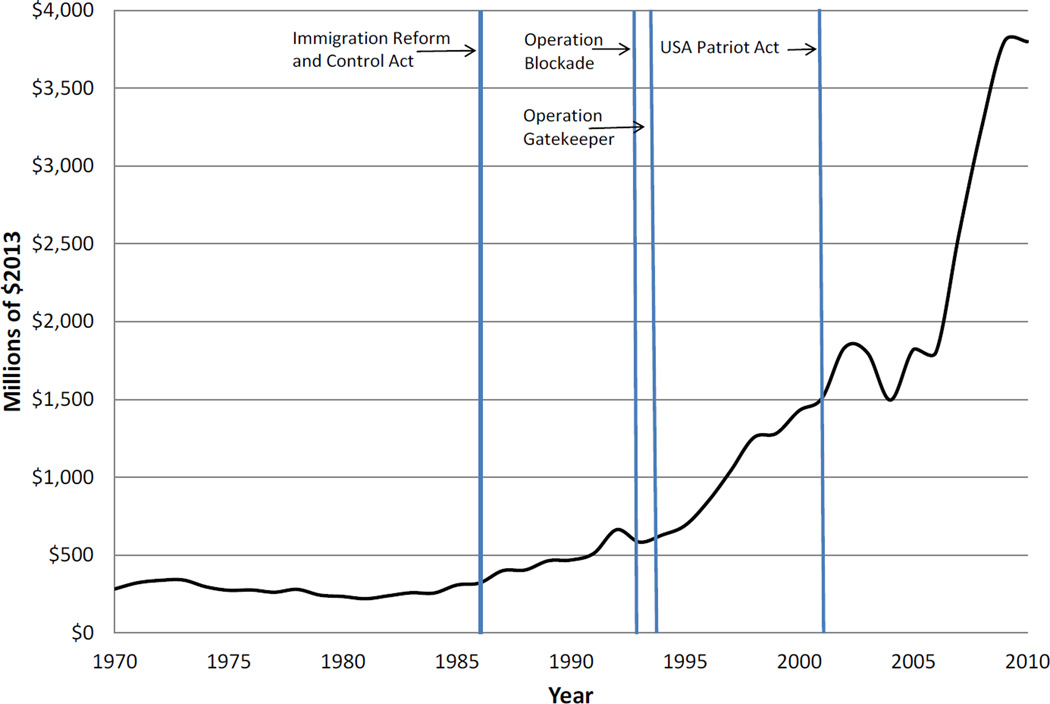

While not grounded in reality, the social construction of the Latino Threat Narrative had profound consequences for the Mexico-U.S. migration system. Figure 1 draws on official data to show the annual budget of U.S. Border Patrol from 1970 to 2010 in constant, inflation-adjusted U.S. dollars. From 1970 through 1985 in real terms the budget fluctuated around a value of $300 million with no trend upward or downward. Withe the Passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986, however, the budget began to increase, accelerating during the 1990s with the launching two intensive border enforcement efforts at the two busiest crossing points—Operation Blockade in El Paso, Texas in 1993 and Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego, California in 1994 (Massey, Durand, and Malone 2002). Border enforcement accelerated again after the passage of the 2001 USA PATRIOT Act and in 2010 the budget stood at $3.8 billion, nearly 13 times its pre-1986 level.

Figure 1.

Border Patrol budget in millions of 2013 dollars

The massive increase in border enforcement and the early concentration of Border Patrol resources in two particular sectors had far-reaching consequences on the behavior of undocumented migrants and the migratory outcomes they could expect at the border, which I document here using data from the Mexican Migration Project (Durand and Massey 2004). Since 1982 the MMP has conducted random household surveys in selected communities throughout Mexico and compiled network samples of households from those same communities in the United States. The accuracy and representativeness of the MMP data have been validated by systematic comparisons with data from nationally representative samples (Massey and Zenteno 2000; Massey and Capoferro 2004) and are publicly available from at the project website (http://mmp.opr.princeton.edu/), which contains complete documentation on sample design, questionnaires, and data files. Here I make use of the MMP143 database, which includes surveys of undocumented migrants originating in 143 Mexican communities.

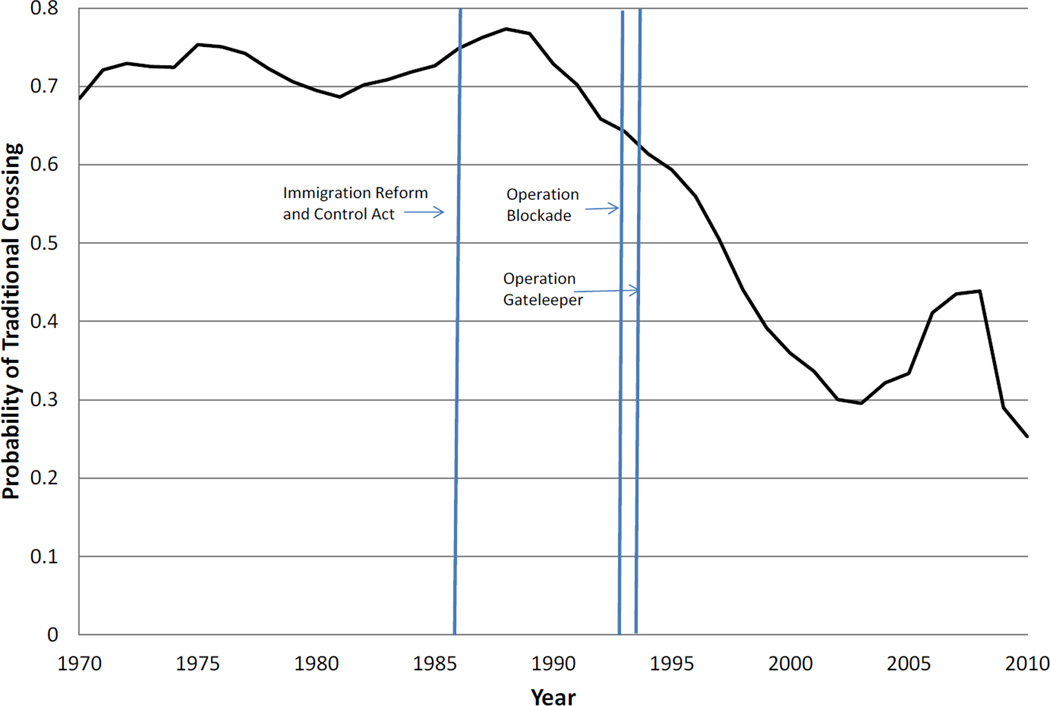

The militarization of the border beginning in 1986 with the passage of IRCA, and especially the launching of Operation Blockade and Operation Gatekeeper in 1993 and 1994, diverted flows of undocumented migrants away from well-traveled routes in the urbanized areas of San Diego and El Paso into unpopulated desert territory between these two sectors. Figure 2 illustrates the geographic diversion that occurred by graphing the probability that undocumented migrants crossed the border at a traditional location (El Paso or San Diego) from 1970 to 2010. While the likelihood fluctuated between 0.69 and 0.77 from 1970 through 1989, thereafter it fell dramatically to reach just 0.25 in 2010. Once diverted away from traditional destinations in states such as California, migrants continued on to new destinations throughout the United States. Thus, whereas 63% of Mexicans who arrived in the United States 1985–1990 went to California, by 1995–2000 the figure had dropped to 28% and new destination areas in the south and midwest came to house the most rapidly growing Mexican populations (Massey and Capoferro 2008).

Figure 2.

Probability of border crossing at a traditional location 1970–2010

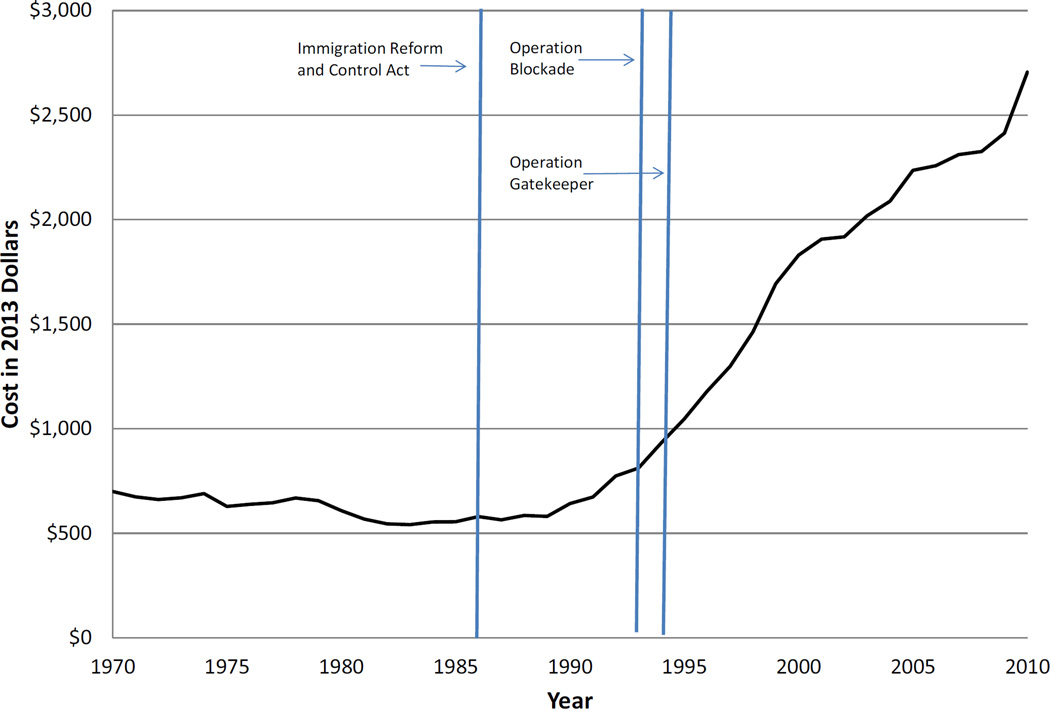

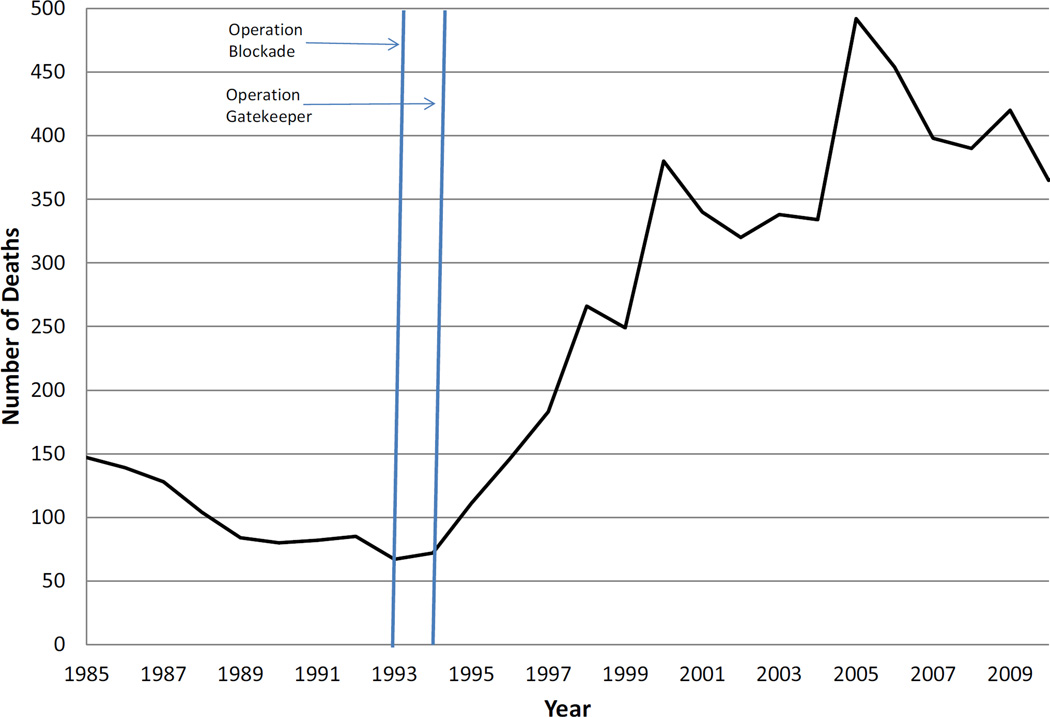

Figure 3 documents the rising costs of border crossing associated with this shift by plotting the average fee paid (in 2010 U.S. dollars) to a “coyote” to be smuggled across the border from 1970 to 2010. Whereas the cost fluctuated between $500 and $700 between 1970 and 1989, thereafter it underwent a sustained increase that culminated in an average cost of $2,700 in 2010, a 450% increase over the average before 1989. Figure 4 documents the increased risks faced by undocumented migrants crossings shifted into more hostile terrain at isolated segments of the border by showing the number of border deaths from 1985 (when estimates first become available) to 2010. From 1985 to 1993, the number of deaths actually fell, going from 147 in the former year to 67 in the latter. Thereafter, deaths along the border proliferated, steadily climbing to peak at almost 500 in 2005.

Figure 3.

Coyote costs paid for undocumented border crossing 1970–2010

Figure 4.

Migrant deaths along the Mexico-U.S. Border 1985–2010

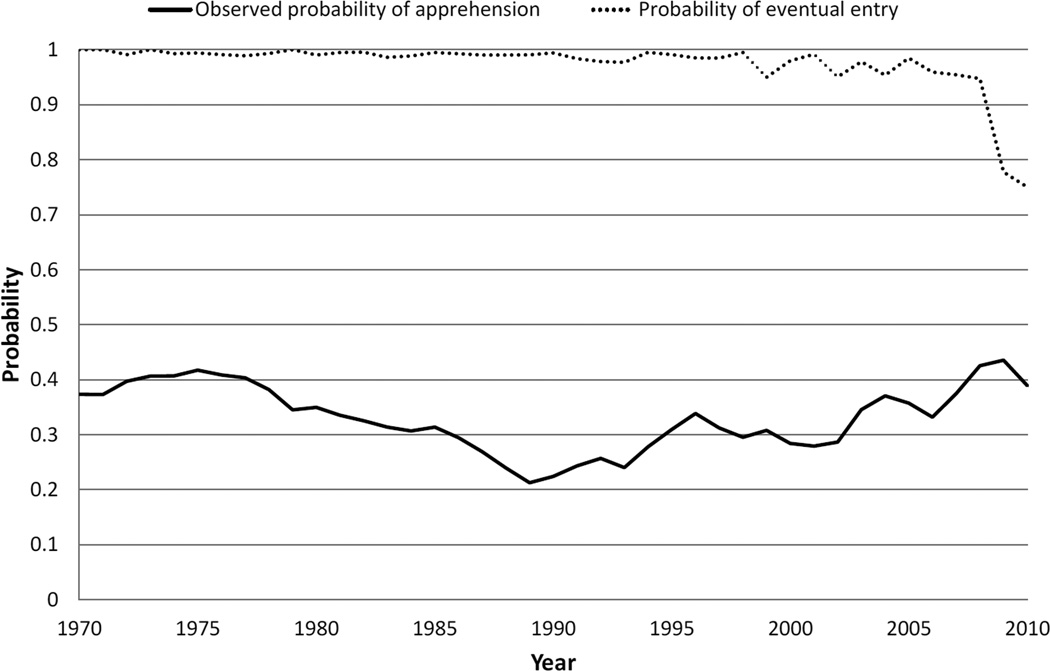

Although rising border enforcement may have had strong effects on the costs, risks, and locations of undocumented border crossing, Figure 5 reveals that it had little effect on the likelihood of being caught while attempting an unauthorized entry. The solid line shows the probability of being apprehended on a first undocumented trip to the United States from 1970 to 2010. As can be seen, the likelihood of getting caught has remained relatively constant despite the massive increase in border enforcement over the past three decades. During the early 1970s the probability of apprehension on any given attempt varied around 0.40 before declining to around 0.21 in 1989 and then rising back up to around 0.40 in 2010. Whatever the likelihood of apprehension on any single attempt, the dotted line at the top of the figure shows the probability of ultimately achieving entry over a series of attempts is and has always been extremely high, being 0.95 or greater from 1970 through 2008.

Figure 5.

Probabilities of apprehension on first attempt and likehood of eventual entry 1970–2010

To this point, I have shown that the build-up in border enforcement after 1986 (depicted in Figure 1) was associated with a sharp drop in the likelihood of crossing the border at traditional, relatively safe urban locations (Figure 2) producing sharp increases in the costs (Figure 3) and risks (Figure 4) of unauthorized entry but had no effect on the likelihood of apprehension or the odds of ultimately achieving entry (Figure 5). These enforcement-induced shifts in outcomes along the border shifted the context of migrant decision-making, however. Whereas before 1986 undocumented migrants knew they could reliably gain entry to the United States at modest cost and low risk, afterward they could still reliably be assured of successful entry but at much greater cost and higher risk to life and limb. As a result, conditions at the border still favored departing for the United States without documents to gain access to high-paying U.S. jobs, but they no longer favored regularly circulating back and forth. Under these circumstances, once a successful entry had been achieved migrants increasingly tended to hunker down and remain north of the border rather than returning to face even greater costs and risks next time.

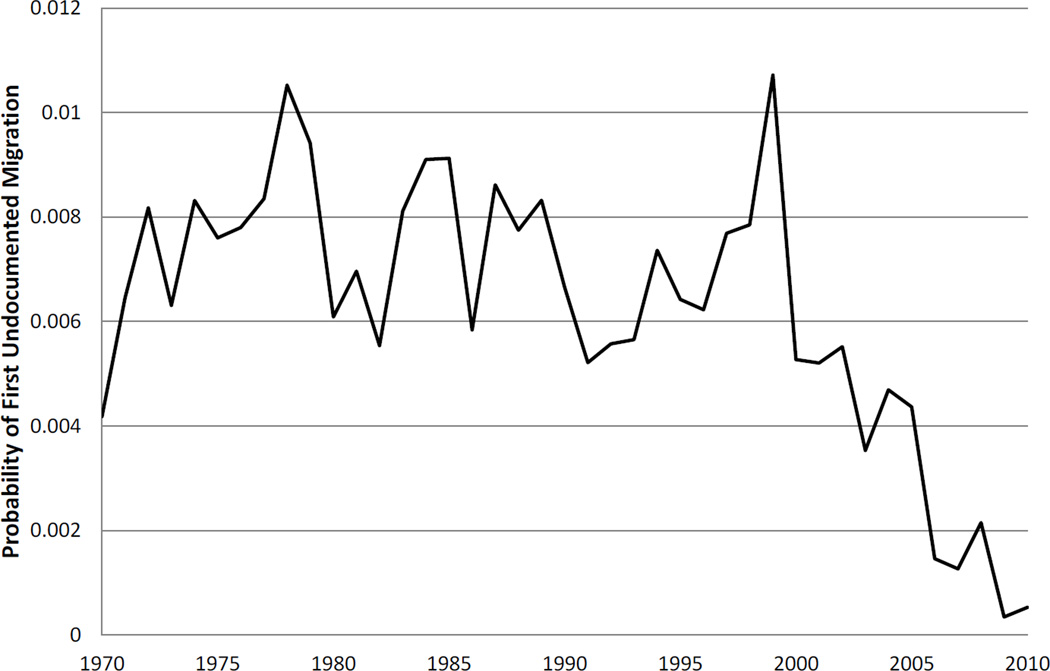

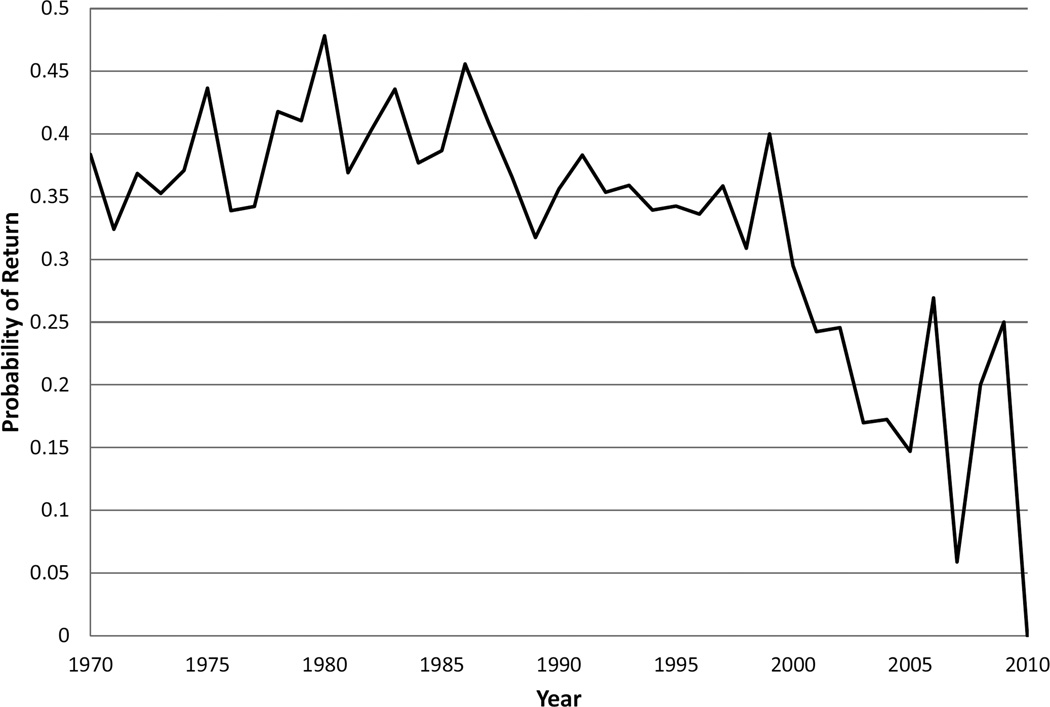

Figures 6 and 7 show the effect that these shifting incentives had on migrant decision-making by plotting, respectively, the likelihood of leaving and returning from a first undocumented trip to the United States between 1970 and 2010. Despite considerable year-to-year volatility there is no discernable trend in the probability of leaving Mexico without documents from 1970 to 2000, despite the exponential increase in enforcement. In contrast, the likelihood of a return trip fell steadily after1986 when it stood at 0.46 to reach 0.29 in 2000 before dropping to zero in 2010.

Figure 6.

Probability of first undocumented migration 1970–2010

Figure 7.

Probability of return within 12 months of first undocumented trip

With undocumented departures continuing at historical rates but returns to Mexico falling rapidly from 1986 to 2000, the net rate of undocumented migration rose and undocumented population growth accelerated. According to the best demographic estimates, the size of the undocumented population increased from 1.9 million in 1988 to 8.5 million in 2000, rising by an average of around 550,000 persons per year (Wasem 2011) After 2000, the rate of growth decelerated and the population peaked at 12 million in 2008. This deceleration corresponds to a steady decline in the likelihood of taking a first undocumented trip from 0.011 to 0.002 between 1999 and 2008. Then with the onset of the Great Recession the undocumented population fell to 11 million by 2009, where it has roughly remained ever since, reflecting the fact that probabilities of undocumented departure and return had both fell to around zero in 2010, as shown in Figures 6 and 7.

CONCLUSION

In the end, changes in U.S. immigration and border policies enacted beginning in 1986 transformed what had been a circular flow of male workers going to three states (California, Texas, and Illinois) into a settled population of families living in 50 states while doubling the net rate of undocumented migration and markedly accelerating undocumented population growth. This transformation occurred not because of shifts in the social and economic variables specified in the theories reviewed by Massey et al. (1998) or because of state actions hypothesized by the theories considered in Massey (1999), but because of actions taken by self-serving bureaucrats, politicians, and pundits who gained power and resources by manufacturing an immigration crisis where none existed.

Although in practical terms little had changed in the Mexico-U.S. migration system after 1965, by curtailing opportunities for legal entry Congress in that year brought about the rise of illegal migration and created a golden opportunity for entrepreneurial agents to create a Latino Threat Narrative centered on the fact that Mexican migrants were “illegal” and thus by definition “criminals” and “lawbreakers” who constituted a grave threat to American society. The propagation of this threat narrative, in turn, drove forward a self-perpetuating cycle of increased border enforcement and rising apprehensions. Even though the volume of undocumented migration had leveled off and stabilized by the late 1970s, additional border enforcement efforts produced more apprehensions, which were taken as self-evident proof of the continuing illegal invasion and the need for more enforcement resources, which produced even more apprehensions to justify the still more resources for enforcement.

The end result of this dynamic cycle was a moral panic centered on the trope of illegality and the border as a barrier between American society and the threats this illegality carried. In the process, pundits sold books, garnered higher media ratings, and increased earnings while politicians mobilized voters to gain power and officials within the immigration bureaucracy accumulated a treasure trove of resources. The massive expansion of the immigration enforcement system, in turn, created a multitude of jobs that made public sector unions happy and increased the profits of firms such as the Corrections Corporation of American and the Geo Group, which built and operated immigration detention facilities. Local law enforcement agencies jumped on the bandwagon when congress created a special program to provide them with new resources to assist in immigration enforcement.

In short, the Latino Threat Narrative was manufactured and sustained by an expanding set of self-interested actors who benefitted from the perpetuation of an immigration crisis, which drove an unprecedented militarization of the border that radically transformed a long-standing migration system from a circularity to settlement. Although the graphs presented here only represent associations, recent work by Massey, Durand, and Pren (2016) using instrumental variable regressions confirm that rising border enforcement was indeed the causal factor driving the geographic diversification of immigrant destinations and the shift from sojourning to settlement among Mexican migrants.

These same regressions also indicate that undocumented migration came to an end in 2008 and is unlikely to return, not because of border enforcement or to changed economic circumstances but as a result of Mexico’s demographic transition from a fertility rate from 7.2 children per woman in 1965 to just 2.3 children per woman today, barely above replacement level. As a result, over the past two decades the rate of labor force growth has fallen and Mexico has become an aging society, with the age of those exposed to the risk of U.S. migration rising rapidly beyond the upper end of the migrant-prone age range. If international migration is not initiated between the ages of 15 and 30, it is unlikely to begin later, and in their study Massey, Durand, and Pren (2016) found that the average age of Mexicans in the labor force but lacking prior migratory experience steadily rose steadily from 23.4 in 1972 to 45.9 in 2010. As a result, net migration from Mexico–not just undocumented migration but migration in general–now hovers around zero (Passel, Cohn, and Gonzalez-Barrera 2012).

The transformation of Mexican immigration from circularity to settlement and its geographic spread throughout the United States between 1986 and 2008 has transformed the social demography of the United States, increasing the percentage of Latinos to 17.3% and making them by far the largest minority group in the United States. Moreover, no matter what the future of Mexican migration might be, this transformation is already built into the demographic structure of the United States for in 2012 for the first time less than half of all U.S. births were to non-Hispanic whites while a quarter were Latino (Passel, Livingston, and Cohn 2012). This remarkable transformation arose from a dynamic sociopolitical process that was completely untheorized by prevailing models of international migration but which in two decades will nonetheless turn the United States into a “minority-majority” nation in which European origin whites no longer predominate.

REFERENCES

- Abrajano Marisa, Hajnal Zoltan L. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2015. Abrajano and Hajnal 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arpaio Joe, Sherman Len. Joe's Law: America's Toughest Sheriff Takes on Illegal Immigration, Drugs and Everything Else That Threatens America. New York: AMACOM Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan Patrick J. State of Emergency: The Third World Invasion and Conquest of America. New York: Thomas Dunne Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Calavita Kitty. Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. New York: Routledge; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman Leonard F. Illegal Aliens: Time to Call a Halt! Reader's Digest. 1976 Oct;:188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso Lawrence. Mexican Emigration to the United States 1897–1931. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez Leo R. Covering Immigration: Population Images and the Politics of the Nation. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez Leo R. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs Lou. War on the Middle Class: How the Government, Big Business, and Special Interest Groups Are Waging War on the American Dream and How to Fight Back. New York: Viking; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Durand Jorge, Massey Douglas S. Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Durand Jorge, Massey Douglas S. Clandestinos: Migración México-Estados Unidos en los Albores del Siglo XXI. México, D.F.: Editorial Porrua; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Durand Jorge, Massey Douglas S. Crossing the Border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dustmann Christian, Görlach Joseph-Simon. The Economics of Temporary Migrations. Journal of Economic Literature. 2015 forthcoming. Pre-publication version available at: http://www.cream-migration.org/publ_uploads/CDP_03_15.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Yeffal Nadia Y. Migration-Trust Networks: Social Cohesion in Mexican US-Bound Emigration. College Station: Texas A&M University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Yeffal Nadia Y, Vidales Guadalupe, Plemons April. The Latino Cyber-Moral Panic Process in the United States. Information, Communication, and Society. 2011;14:568–489. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell Elizabeth, Massey Douglas S. The Limits to Cumulative Causation: International Migration from Mexican Urban Areas. Demography. 2004;41:151–171. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner Daniel. The Science of Fear: Why We Fear the Things We Shouldn't--and Put Ourselves in Greater Danger. New York: Dutton; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garip Filiz. Discovering Diverse Mechanisms of Migration: The Mexico-U.S. Stream from 1970 to 2000. Population and Development Review. 2012;38(3):393–433. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington Samuel P. The Hispanic challenge. Foreign Policy. 2004 Mar-Apr;:1–12. Accessed 6/15/11 at http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=2495. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. International Migration and Economic Development in Comparative Perspective. Population and Development Review. 1988;14:383–414. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration. Population Index. 1990;56:3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. International Migration at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century: The Role of the State. Population and Development Review. 25:303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Building a Comprehensive Model of International Migration. Eastern Journal of European Studies. 2013;3(2):9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Alarcón Rafael, Durand Jorge, González Humberto. Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Arango Joaquín, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, Taylor J Edward. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review. 1993;19:431–466. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Arango Joaquín, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, Taylor J Edward. An Evaluation of International Migration Theory: The North American Case. Population and Development Review. 1994;20:699–752. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Arango Joaquín, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, Taylor J Edward. Worlds in Motion: International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Brown Amelia E. New Migration Streams between Mexico and Canada. Migraciones Internactionales. 2011;6(1):119–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Capoferro Chiarra. Measuring Undocumented Migration. International Migration Review. 2004;38:1075–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Capoferro Chiarra. The Geographic Diversification of U.S. Immigration. In: Massey Douglas S., editor. New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration. New York: Russell Sage; 2008. pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Malone Nolan J. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Age of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Pren Karen A. Explaining Undocumented Migration. International Migration Review. 2014;48:1028–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Pren Karen A. Why Border Enforcement Backfired. American Journal of Sociology. 2016 doi: 10.1086/684200. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Espinosa Kristin E. What's Driving Mexico-U.S. Migration? A Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Analysis. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;102:939–999. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Pren Karen A. Origins of the New Latino Underclass. Race and Social Problems. 2012a;4(1):5–17. doi: 10.1007/s12552-012-9066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Pren Karen A. Unintended Consequences of US Immigration Policy: Explaining the Post-1965 Surge from Latin America. Population and Development Review. 2012b;38:1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Taylor J Edward. International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Global Market. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Zenteno René. The Dynamics of Mass Migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96(8):5328–5335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Zenteno René. A Validation of the Ethnosurvey: The Case of Mexico-U.S. Migration. International Migration Review. 2000;34:765–792. [Google Scholar]

- North Douglass S. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera, Gonzalez-Barrera Ana. Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero-and Perhaps Less. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2012. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/23/net-migration-from-mexico-falls-to-zero-and-perhaps-less/ [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Livingston Gretchen M, Cohn D’Vera. Explaining Why Minority Births Now Outnumber White Births. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2012. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/05/17/explaining-why-minority-births-now-outnumber-white-births/ [Google Scholar]

- Piore Michael J. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor in Industrial Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Bach Robert L. Latin Journey: Cuban and Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Walton John. Labor, Class, and the International System. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Robin Corey. Fear: The History of a Political Idea. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana Otto. Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse. Austin: University of Texas Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen Saskia. The Mobility of Labor and Capital: A Study in International Investment and Labor Flow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Oded. The Migration of Labor. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Walter G, Renfro Lausane. The Role of Threat in Intergroup Relations. In: Mackie DM, Smith ER, editors. From Prejudice to Intergroup Emotions: Differentiated Reactions to Social Groups. New York: Psychology Press; 2002. pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Walter G, Ybarra Oscar, Morrison Kimberly Rios. Intergroup Threat Theory. In: Nelson T, editor. Handbook of Prejudice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J Edward, Arango Joaquin, Massey Douglas S, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela. International Migration and National Development. Population Index. 62:181–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J Edward, Arango Joaquin, Massey Douglas S, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela. International Migration and Community Development. Population Index. 1996;63:397–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro Michael P, Maruszko L. Illegal Migration and U.S. Immigration Reform: A Conceptual Framework. Population and Development Review. 1986;13:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino Nicholas A, Brader Ted, Jardina Ashley E. Immigration Opposition Among U.S. Whites: General Ethnocentrism or Media Priming of Attitudes About Latinos? Political Psychology. 2013;34:149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wasem Ruth E. Unauthorized Aliens Residing in the United States: Estimates Since 1986. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson Jeffrey G. The Political Economy of World Mass Migration: Comparing Two Global Centuries. Washington, DC: AEI Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]