Abstract

Interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) is a tumor-suppressor gene induced by interferon-γ (IFNγ) and plays an important role in the cell death of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC tumors evade death in part by downregulating IRF-1 expression, yet the molecular mechanisms accounting for IRF-1 suppression in HCC have not yet been characterized. Previous studies have shown that microRNA-23a (miR-23a) can suppress apoptosis by targeting IRF-1. Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-23a promotes HCC growth by down-regulating IRF-1. For the in vivo studies, 7 cases of resected HCC and adjacent liver samples were analyzed. For the in vitro studies, IRF-1 mRNA and protein were examined in HepG2 and Huh-7 HCC cells after IFNγ stimulation by real-time PCR and western blotting, respectively. To determine the role of miR-23a in regulating IRF-1, HepG2 cells were transfected with an miR-23a mimic or inhibitor, and IRF-1 expression was examined. Binding of miR-23a was assessed by cloning the 528-bp human IRF-1 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) into luciferase reporter plasmid pMIR-IRF-1-3′UTR. The results showed that IRF-1 mRNA expression was down-regulated in the human HCC tumor tissues compared to that in the adjacent background liver tissues. IFNγ-induced IRF-1 protein was less in the HepG2 tumor cells compared to that in the primary human hepatocytes. miR-23a expression was inversely correlated with IRF-1, and addition of the miR-23a inhibitor increased basal IRF-1 mRNA and protein. Likewise, the miR-23a mimic downregulated IFNγ-induced IRF-1 protein expression, while the miR-23a inhibitor increased IRF-1. Furthermore, the miR-23a mimic repressed IRF-1-3′UTR reporter activity, while the miR-23a inhibitor increased the reporter activity. These results demonstrated that IRF-1 expression is downregulated in human HCC tumors compared to that noted in the background liver. miR-23a downregulates the expression of IRF-1 in HCC cells, and the IRF-1 3′UTR has an miR-23a binding site that binds miR-23a and decreases reporter activity. These findings suggest that the targeting of IRF-1 by miR-23a may be the molecular basis for IRF-1 downregulation in HCC and provide new insight into the regulation of HCC by miRNAs.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, interferon regulatory factor-1, microRNA-23a

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, and commonly leads to cancer-related mortality (1). The molecular mechanisms involved in HCC carcinogenesis are a focus of extensive investigation. The cell signaling effects of mutagens on specific HCC oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes have been reported.

Interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) was identified as an IFN-inducible master transcription factor that plays important roles in immunity and oncogenesis (2). IRF-1 has been identified as a tumor-suppressor gene through regulation of the cell cycle and apoptosis in addition to its function in immunomodulation and antiviral response (3–8).

Our previous study found that interferon-γ (IFNγ) induced autophagy in HCC cells through IRF-1 (9). Additionally, aberrant expression of IRF-1 has been found in many malignant tumors including melanoma, leukemia, gastric and breast cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (10). Carcinogenesis signaling in HCV-mediated HCC was found to be related to suppression of IRF-1, and downregulation of IRF-1 was found to predict a poor prognosis in HCC (11,12). However, the molecular mechanisms of IRF-1-mediated suppression of HCC growth are not well defined.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules of 20–30 nucleotides which specifically recognize and suppress particular mRNAs at the post-transcriptional level by exerting a translational blockade or causing degradation of mRNAs (13). This regulation is involved in fundamental cellular processes, including cell cycle, differentiation, metabolism, as well as carcinogenesis and tumor progression (14). Furthermore, miRNAs are frequently observed to be dysregulated in HCC (15,16). Recently, a study found that 193 miRNAs were differentially expressed in an HCC cell line compared to normal liver cells (17). microRNA-23a (miR-23a), located in the miR-23a/24/27a cluster, has been shown to be upregulated in HCC, and can suppress apoptotic activities in HCC cells (15,16,18,19). IFNγ stimulation of melanoma cells showed that miR-23a is inversely associated with IRF-1 (20). Additionally, research has demonstrated that miR-23a targets IRF-1 to suppress the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells and facilitates the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 in HeLa cells (21,22).

In the present study, we showed that IRF-1 expression was decreased in primary human HCC tumors and human HCC cell lines. The expression of IRF-1 induced by IFNγ in hepatocytes and HCC cells demonstrated that miR-23a is inversely correlated to IRF-1. We identified an miR-23a binding site in the 3′-untranslated region (3-UTR) of the human IRF-1 gene and showed that miR-23a decreased the post-transcriptional expression of IRF-1. These findings suggest that the targeting of IRF-1 by miR-23a may be a molecular basis for IRF-1 downregulation in HCC and provide new insight into the regulation of HCC by miRNAs.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of human tissue specimens

Seven paired HCC and adjacent liver tissues were obtained from patients who underwent hepatectomy at the Liver Cancer Center of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). All human tissues were acquired in accordance with the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol.

Cell lines

The primary human hepatocytes (hHCs) were isolated at the University of Pittsburgh as part of the NIH-funded Liver Tissue and Cell Distribution System. The hepatocytes were used immediately following receipt and cultured in Williams' medium E (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) with 5% newborn calf serum. The human HCC cell lines Huh-7 and HepG2 and colon cancer cell line HCT116 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA). Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Lonza), while HCT116 cells were cultured with McCoy's 5A medium (Gibco/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 15 mmol/l HEPES and 200 mmol/l L-glutamine. All cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, 1 µg of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed to single-stranded cDNA with RNA to cDNA EcoDry™ Premix (Clontech). One microliter of cDNA was diluted 50-fold with nuclease-free water and used as a template for the following qRT-PCR. The IRF-1 mRNA expression was quantified using the IRF-1 primer, as well as the SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix with the StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR system (both from Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The IRF-1 primers were: 5′-ACCCTGGCTAGA GATGCAGA-3′ (forward), and 5′-GCTTTGTATCGGCCTGTGTG-3′ (reverse); GAPDH primers were: 5′-GGGAAGCTTGTCATCAATGG-3′ (forward), and 5′-CATCGCCCCACTTGATTTTG-3′ (reverse). The qPCR cycling conditions used were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min, 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Exponential amplification had been confirmed up to 40 cycles of the amplification. The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All primers were purchased from Invitrogen.

miR-23a expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR using TaqMan miRNA assays according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription reactions were prepared using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each 15 µl multiplex reaction contained 10 ng total RNA as template. Prior to real-time PCR, the multiplex RT-reactions were diluted with 100 µl nuclease-free water. The diluted RT-products were mixed with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, without UNG (Applied Biosystems). U6 snRNA was used for normalization. miR-23a and U6 snRNA primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The qPCR cycling conditions used were as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔct method.

Western blotting

Whole protein was extracted with cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Nuclear protein was extracted as previously described (23). A total of 20 µg of nuclear protein was electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoide membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-IRF-1 or lamin A/C (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies overnight, respectively. Lamin A/C was used as a loading control. Then, the membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline and Tween-20 (TBST) for three times, and incubated with a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h, and developed onto X-ray film using chemiluminescent reagent.

Cell infection

The adenovirus of the miR-23a inhibitor (admiRa-has-miR-23a-Off Virus) and its negative control (NC) (admiR-23a-Off Negative Control Virus) were purchased from Applied Biological Materials (Richmond, BC, Canada), and were amplified by the Vector Core Facility at the University of Pittsburgh. Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were infected for 48 h with either the ad-NC adenovirus or the ad-miR-23a inhibitor. After 48 h of infection, the cells were harvested, and then total RNA and nuclear protein were extracted to determine the expression of IRF-1.

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was performed according to our previous study (9). Huh-7 cells were cultured on coverslips, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% FBS in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and incubated with the primary IRF-1 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h, which was diluted in a 1:150 ratio. Next, Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:500; Invitrogen) was applied for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the slides were stained with 4′,6-diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) and mounted, and then observed with a Olympus Fluoview FV1000 II microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Plasmid construct

pMIR-IRF-1-3′UTR plasmid was subcloned into the multicloning site of the retroviral vector. The 528-bp of the human IRF-1 3′UTR sequence containing the miR-23a binding site was amplified by PCR from cDNA of the HCC cell line Huh-7 and inserted into the cloning site to construct pMIR-IRF-1-3′UTR. The primers were: 5′-AAA ACTAGTAGTGTCTGGCTTTTTCCTCTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTAAGCTTATGACATTTCCAATTTTAA-3′ (reverse). The recombinant plasmid was re-cut with endonuclease HindIII and SacI and sequenced and compared with BLAST for confirmation.

Transfection

The mirVana™ miRNA mimics and inhibitor of hsa-miR-23a-3p were transfected in cells in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 48 h according to the manufacturer's protocol. miR-23a-3p mimics and inhibitors were purchased from Ambion (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The procedure was followed according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the luciferase assay, the pMIR-IRF-1-3′UTR plasmid was transfected into cells in 12-well plates using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) for 48 h.

Luciferase assay

The pMIR-REPORT™ miRNA expression reporter vector system (Applied Biosystems) was used to evaluate miRNA regulation and the β-gal reporter control plasmid was used to normalize the transfection efficiency. HCT116 and HepG2 cells were cultured in a 12-well plate and transfected with 200 ng β-gal combined with 500 ng of the pMIR-REPORT empty vector or pMIR-IRF-1-3′UTR plasmid. Furthermore, the cells were co-transfected with the pMIR-IRF-1-3′UTR plasmid and 50 pmol of the miR-23a mimic, inhibitor and its NC (Ambion), respectively. miRNA NC was used to normalize the total volume for transfection. Serum-free medium was replaced with growth medium after 6 h. Relative luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured with the reporter lysis buffer and luciferase substrate (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The cells were lysed 48 h after transfection. The relative luciferase unit (RLU) was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Report Assay (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used for raw data analysis and a value of p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

IRF-1 expression is repressed in HCC tumors and HCC cell lines

In the in vivo studies, IRF-1 mRNA expression was down-regulated in 7 of the 7 human HCC tumor tissues compared to that in the adjacent background liver (Fig. 1A and B). In the in vitro studies, expression levels of IFNγ-stimulated IRF-1 mRNA and protein were compared in the human hepatocye (hHC) cultures and HCC (Huh-7 and HepG2) cell lines. IRF-1 mRNA and protein was induced by IFNγ in a time-dependent manner; however, the magnitude of induction was markedly less in the HCC tumor cells compared to that in the primary hHCs (Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1.

Expression of interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) is suppressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). (A) IRF-1 mRNA expression in 7 cases of HCC was decreased compared with the expression level in adjacent non-cancerous background liver samples. The IRF-1 mRNA level was quantified by qPCR. (B) IRF-1 mRNA levels were significantly lower in the HCC compared to the non-cancerous liver samples (**p<0.001). (C) IRF-1 mRNA levels induced by IFNγ (250 IU/ml) stimulation for 3–24 h were lower in the Huh-7 tumor cells compared to primary human hepatocytes (hHCs). IRF-1 mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR. (D) IRF-1 protein levels in the HepG2 cells were lower than hHCs when induced by IFNγ (250 IU/ml) at 3–6 h. IRF-1 nuclear protein was measured by western blotting and lamin A/C was used as a loading control. Results shown are representative of three similar experiments.

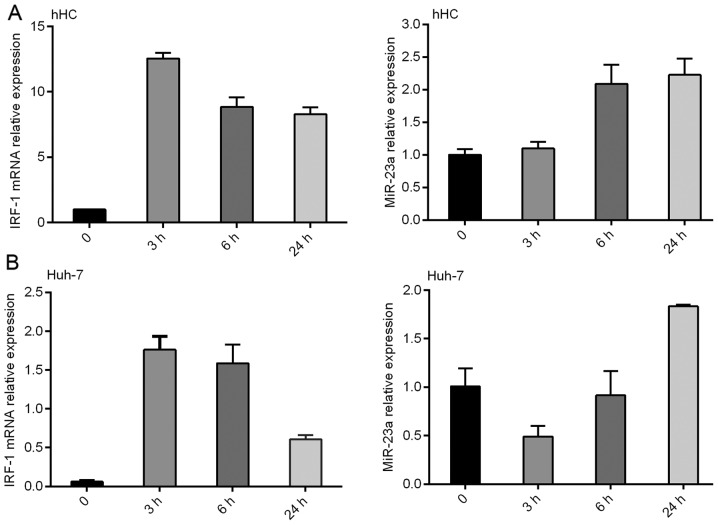

miR-23a expression is inversely correlated with IRF-1 mRNA in the HCC cell lines induced by IFNγ

IFNγ induced IRF-1 mRNA expression in the primary hHCs and Huh-7 HCC cells in a time-dependent manner, with a peak IRF-1 mRNA level observed at 3 h, which was decreased by 24 h (Fig. 2). Notably, miR-23a expression was also increased by IFNγ, however the induction peaked at 24 h and was inversely correlated with IRF-1 mRNA induction.

Figure 2.

Expression of miR-23a is inversely correlated with IRF-1 mRNA in (A) primary human hepatocytes (hHC) and (B) HCC Huh-7 cells induced by IFNγ (250 IU/ml) for 3–24 h. Results shown are representative of three similar experiments.

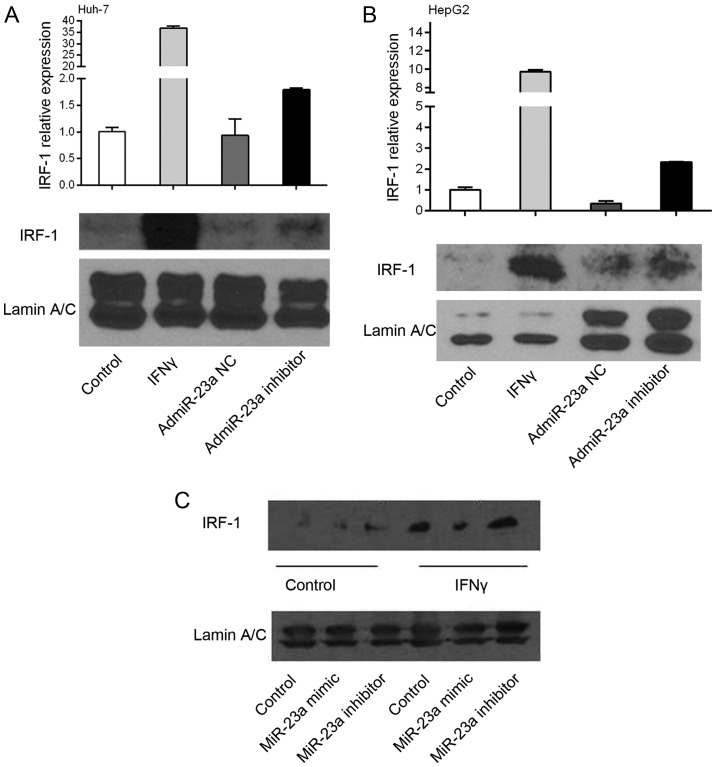

miR-23a downregulates expression of IRF-1

To determine a cause/effect relationship between miR-23a and IRF-1 expression, human HCC Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were infected with the adenovirus overexpressing the miR-23a (admiR-23a) inhibitor or NC. The miR-23a inhibitor increased basal IRF-1 mRNA levels 2 to 3-fold as determined by real-time PCR, while the NC had no effect (Fig. 3A and B). These findings suggest that endogenous miR-23a suppresses basal IRF-1 mRNA levels in tumor cells, since the inhibitor increased basal IRF-1 mRNA. As expected, IFNγ markedly induced IRF-1 mRNA expression, however addition of the miR-23a inhibitor did not further increase the IRF-1 mRNA (data not shown). Basal IRF-1 nuclear protein levels in the HepG2 cells were increased by the miR-23a inhibitor. In contrast, miR-23a mimic decreased IFNγ-induced IRF-1 nuclear protein levels, while the miR-23a inhibitor had no significant effect compared to IFNγ alone (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

IRF-1 expression is downregulated by miR-23a. IRF-1 mRNA expression as determined by real-time PCR was induced by IFNγ stimulation in (A) Huh-7 and (B) HepG2 cells. miR-23a inhibitor increased basal IRF-1 mRNA levels, while the miR-23a negative control (NC) had no effect. (C) The basal IRF-1 nuclear protein level in the HepG2 cells was increased by the miR-23a inhibitor. In contrast, the miR-23a mimic decreased the IFNγ-induced IRF-1 nuclear protein level, while the miR-23a inhibitor had no significant effect compared to IFNγ alone. IRF-1 protein levels were measured by western blotting. IFNγ (250 IU/ml) for 6 h. Results shown are representative of two similar experiments.

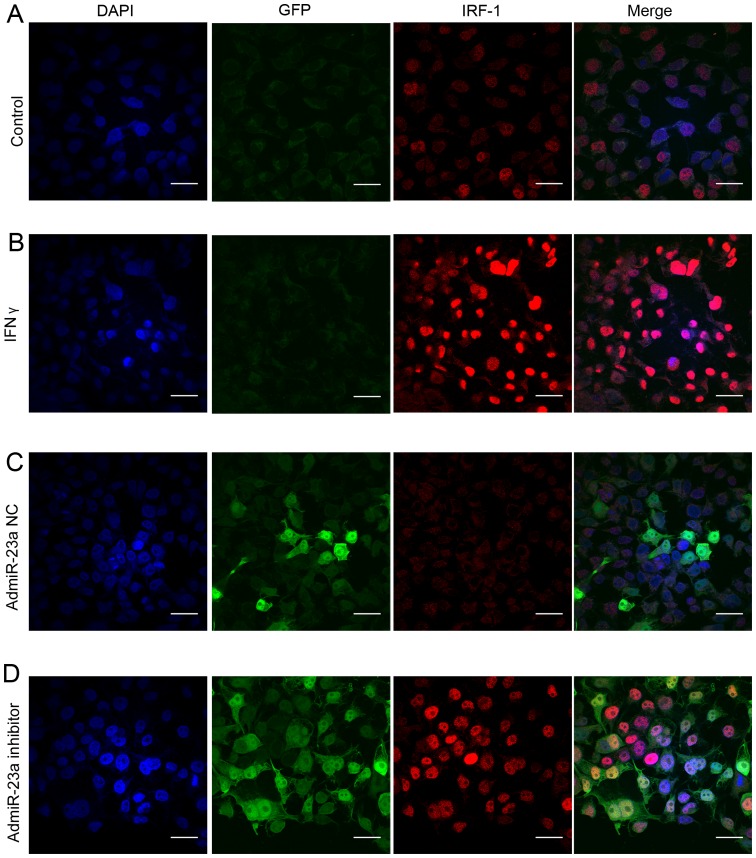

To observe the expression of IRF-1 nuclear protein in the HCC cells, confocal immunofluorescent staining was performed in human Huh-7 cells. Only minimal basal IRF-1 nuclear protein was observed in resting Huh-7 cells (Fig. 4A). As expected, IFNγ strongly induced IRF-1 nuclear protein staining (Fig. 4B). Infection with the admiR-23a inhibitor increased basal IRF-1 nuclear protein expression (Fig. 4D), while the NC had no effect (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

IRF-1 nuclear protein in Huh-7 liver tumor cells is increased by the miR-23a inhibitor. (A) Immunofluorescent staining of IRF-1 nuclear protein in Huh-7 cells shows low basal expression (scale bar, 10 µm). (B) IFNγ (250 IU/ml, 6 h) strongly induced IRF-1 nuclear protein expression in the Huh-7 cells. (C) Expression of miR-23a inhibitor negative control (admiR-23a NC infection for 48 h) did not alter basal IRF-1 protein. (D) Expression of miR-23a inhibitor (admiR-23a inhibitor infection for 48 h) increased basal IRF-1 protein.

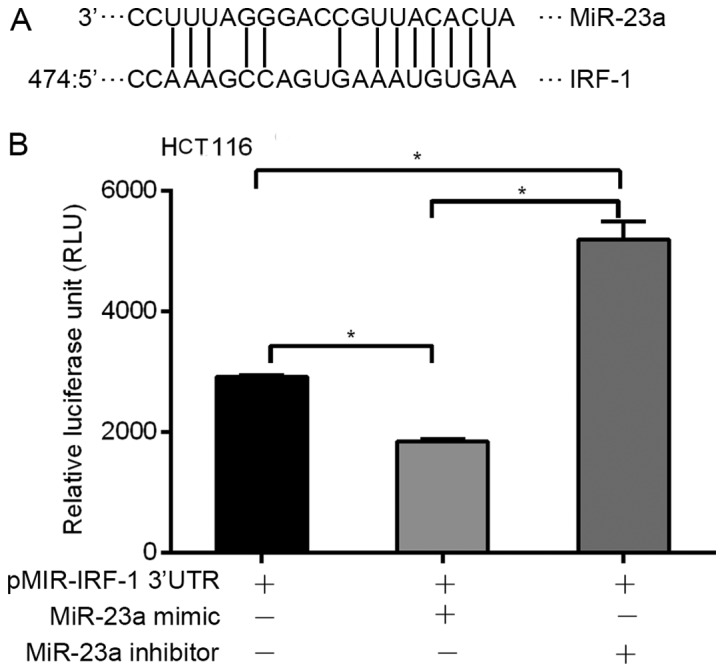

miR-23a targets the specific binding site in the IRF-1 mRNA 3′UTR

miRNAs are known to modulate gene expression by binding to specific miRNA sequences in the 3′UTR of target genes. Therefore, we used MicroInspector software to identify putative miR-23a binding sequence(s) in the 3′UTR of the human IRF-1 mRNA. An miR-23a binding sequence match was identified at nucleotide 474 in the 528-base pair (bp) IRF-1 3′UTR (Fig. 5A). To show a functional role for this binding site, the 528-bp human IRF-1 3′UTR was cloned into a luciferase reporter plasmid pMIR-IRF-1 3′-UTR and transfected into human HCT116 cells. Addition of the miR-23a mimic significantly decreased basal luciferase reporter activity, while addition of the miR-23a inhibitor significantly increased basal reporter activity (Fig. 5B). Transfection with the β-galactosidase expression plasmid was used to control for transfection efficiency (data not shown). These results suggest that miR-23a binds to the human IRF-1 3′UTR region, and suppresses post-transcriptional activity.

Figure 5.

miR-23a regulates IRF-1 mRNA by binding to the IRF-1 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR). (A) Bioinformatic analysis indicated a putative miR-23a-specific binding site in the IRF-1 3′UTR. (B) IRF-1 3′UTR luciferase reporter activity was decreased by the miR-23a mimic, and increased by the miR-23a inhibitor in the HCC HCT116 cells (*p<0.05). Results shown are representative of two similar experiments.

Discussion

IRF-1 functions as a tumor-suppressor gene to inhibit the oncogenesis and progression of malignant tumors through regulation of apoptosis and the cell cycle. DNA damage-inducing cell apoptosis relies on the cooperation of IRF-1 and p53 pathways (24). Additionally, IRF-1 binds to distinct sites in the promoter with upregulation of p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) to activate apoptosis (7). In a previous study, we identified that IFNγ induced autophagy in HCC cells through IRF-1 (9). In the present study, we investigated the mechanism by which IRF-1 is repressed in HCC. The major and novel findings were as follows. i) IRF-1 expression was downregulated in the resected human HCC tumors compared to that observed in the background liver. ii) miR-23a downregulates the expression of IRF-1 in HCC cells; and iii) the IRF-1 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) has a miR-23a binding site that binds miR-23a and decreases post-transcriptional activity. These findings suggest that miR-23a targeting IRF-1 may be the molecular basis for IRF-1 down-regulation in HCC and provide new insight into the regulation of HCC by miRNAs.

IRF-1 regulates cell apoptosis induced by DNA damage, which is dependent on cell type and differentiation (7,25). IFNγ induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells through IRF-1 resulting in caspase cleavage and reduced expression of the apoptosis-suppressor gene survivin independent of p53, in addition to cell cycle arrest dependent on upregulation of p21 (6,26). The expression of IRF-1 has been shown to be reduced in several types of malignant tumors and we observed that the basal level of IRF-1 was suppressed in IFNγ-induced HCC cell lines as well as in HCC tissues when compared to that in adjacent non-cancerous tissues, which may account for the oncogenesis and progression of HCC.

Several possible mechanisms have been reported to account for the inability of IRF-1 to exert a tumor-suppressor effect. The genetic alteration of the IRF-1 genotype with loss of heterozygosity in leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) as well as loss of one IRF-1 allele in esophageal and gastric cancers has been reported (10,25). Additionally, inactivation of IRF-1 has been demonstrated in various types of cancers. Upregulation of nucleophosmin to inhibit the function of IRF-1 was observed in myeloid leukemia cells (27). A low level of IRF-1 mRNA was discovered in breast cancer and HCC (10,25).

In the present study, we investigated the role of the specific miR-23a in the post-transcriptional regulation of IRF-1. Previous studies demonstrated increased expression of miR-23a in HCC along with anti-apoptotic function and subsequent promotion of tumor proliferation (18,19). In addition, miR-23a was believed to play a role in gluconeogenesis in HCC, which is involved in the process of liver tumorigenesis and correlates with the prognosis of HCC (28). Furthermore, miR-23a was noted to play a role in regulating tumor cell response to chemotherapeutic agents (29).

We observed that miR-23a and IRF-1 mRNA are inversely expressed in human hepatocytes (hHCs) and HCC cell lines induced by IFNγ. The miR-23a inhibitor increased basal expression of IRF-1 in the HCC cells, while a specific miR-23a mimic suppressed IFNγ-induced IRF-1 expression. These findings add new important information to the complex signaling pathways in inflammation-associated carcinogenesis.

Previously studies have shown that miRNAs regulate hundreds of genes via inducing mRNA degradation or prohibiting gene translation by direct binding to the 3′UTR of target mRNAs (29–31). Indeed we identified an miR-23a binding site in the 3′UTR of the human IRF-1 mRNA, and showed that this 3′UTR was responsive to the miR-23a mimic and inhibitor in the reporter assays. These findings are consistent with a recent study showing that miR-23a targets IRF-1 and modulates cell proliferation and paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in gastric cancer (21). Moreover, miR-23b was shown to have an important role in promoting avian leukosis virus subgroup J (ALV-J) replication by binding the IRF-1-specific sequence (32). Another group showed that IFNγ could induce miR-29b by recruiting IRF-1 to binding sites in the miR-29b promoter in colorectal cancer (31). In a related study, IRF-1 was found to regulate miR-203 transcription by binding to the miR-203 promoter in cervical cancer (33).

In summary, these results demonstrated that IRF-1 expression is downregulated in resected human HCC tumors compared to background liver. miR-23a inhibition increases basal expression of IRF-1, and the finding of a functional miR-23a binding site in the 3′UTR of the human IRF-1 gene suggests that miR-23a mediates post-transcriptional suppression of IRF-1. Taken together, these findings are consistent with the notion that the targeting of IRF-1 by endogenous miR-23a may be the molecular basis for IRF-1 downregulation in HCC. These findings also provide new insight into the regulation of HCC by miRNAs during inflammatory conditions.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the NIH HHSN2762 01200017C Liver Tissue and Cell Distribution System (LTCDS) contract (D.A.G.), and the NIH grant 1S10OD019973-01 from the Center for Biologic Imaging at the University of Pittsburgh. We thank Nicole Martik-Hays and Kimberly Ferrero for isolating the hHCs.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connett JM, Hunt SR, Hickerson SM, Wu SJ, Doherty GM. Localization of IFN-gamma-activated Stat1 and IFN regulatory factors 1 and 2 in breast cancer cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:621–630. doi: 10.1089/107999003322558755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yim JH, Ro SH, Lowney JK, Wu SJ, Connett J, Doherty GM. The role of interferon regulatory factor-1 and interferon regulatory factor-2 in IFN-gamma growth inhibition of human breast carcinoma cell lines. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:501–511. doi: 10.1089/10799900360708623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim PK, Armstrong M, Liu Y, Yan P, Bucher B, Zuckerbraun BS, Gambotto A, Billiar TR, Yim JH. IRF-1 expression induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth in mouse mammary cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2004;23:1125–1135. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stang MT, Armstrong MJ, Watson GA, Sung KY, Liu Y, Ren B, Yim JH. Interferon regulatory factor-1-induced apoptosis mediated by a ligand-independent fas-associated death domain pathway in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:6420–6430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Senthil M, Ren B, Yan J, Xing Q, Yu J, Zhang L, Yim JH. IRF-1 transcriptionally upregulates PUMA, which mediates the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in IRF-1-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:699–709. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong MJ, Stang MT, Liu Y, Yan J, Pizzoferrato E, Yim JH. IRF-1 inhibits NF-κB activity, suppresses TRAF2 and cIAP1 and induces breast cancer cell specific growth inhibition. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:1029–1041. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1046646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li P, Du Q, Cao Z, Guo Z, Evankovich J, Yan W, Chang Y, Shao L, Stolz DB, Tsung A, et al. Interferon-γ induces autophagy with growth inhibition and cell death in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells through interferon-regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) Cancer Lett. 2012;314:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanai H, Negishi H, Taniguchi T. The IRF family of transcription factors: Inception, impact and implications in oncogenesis. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1376–1386. doi: 10.4161/onci.22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esmat G, El-Bendary M, Zakarya S, Ela MA, Zalata K. Role of Helicobacter pylori in patients with HCV-related chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis with or without hepatocellular carcinoma: Possible association with disease progression. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:473–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi Y, Wu H, Gao Q, He HW, Li YW, Cai XY, Wang JX, Zhou J, Cheng YF, Jin JJ, et al. Interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1 and IRF-2 are associated with prognosis and tumor invasion in HCC. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:267–276. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2487-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lujambio A, Lowe SW. The microcosmos of cancer. Nature. 2012;482:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otsuka M, Kishikawa T, Yoshikawa T, Ohno M, Takata A, Shibata C, Koike K. The role of microRNAs in hepato-carcinogenesis: Current knowledge and future prospects. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:173–184. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Anzeo M, Faloppi L, Scartozzi M, Giampieri R, Bianconi M, Del Prete M, Silvestris N, Cascinu S. The role of micro-RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma: From molecular biology to treatment. Molecules. 2014;19:6393–6406. doi: 10.3390/molecules19056393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai Y, Xue Y, Xie X, Yu T, Zhu Y, Ge Q, Lu Z. The RNA expression signature of the HepG2 cell line as determined by the integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression profiles. Gene. 2014;548:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He XX, Kuang SZ, Liao JZ, Xu CR, Chang Y, Wu YL, Gong J, Tian DA, Guo AY, Lin JS. The regulation of microRNA expression by DNA methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:532–539. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00563E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang S, He X, Ding J, Liang L, Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Yao X, Pan Z, Zhang P, Li J, et al. Upregulation of miR-23a~27a~24 decreases transforming growth factor-beta-induced tumor-suppressive activities in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:972–978. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nazarov PV, Reinsbach SE, Muller A, Nicot N, Philippidou D, Vallar L, Kreis S. Interplay of microRNAs, transcription factors and target genes: Linking dynamic expression changes to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2817–2831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Ru J, Zhang J, Zhu LH, Liu M, Li X, Tang H. miR-23a targets interferon regulatory factor 1 and modulates cellular proliferation and paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in gastric adenocarcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Ru J, Sun H, Fan H, Wang C, Li Y, Liu M, Tang H. MiR-23a facilitates the replication of HSV-1 through the suppression of interferon regulatory factor 1. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao L, Guo Z, Geller DA. Transcriptional suppression of cytokine-induced iNOS gene expression by IL-13 through IRF-1/ISRE signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:582–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka N, Ishihara M, Lamphier MS, Nozawa H, Matsuyama T, Mak TW, Aizawa S, Tokino T, Oren M, Taniguchi T. Cooperation of the tumour suppressors IRF-1 and p53 in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1996;382:816–818. doi: 10.1038/382816a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen FF, Jiang G, Xu K, Zheng JN. Function and mechanism by which interferon regulatory factor-1 inhibits oncogenesis. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:417–423. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong MJ, Stang MT, Liu Y, Gao J, Ren B, Zuckerbraun BS, Mahidhara RS, Xing Q, Pizzoferrato E, Yim JH. Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) induces p21WAF1/CIP1 dependent cell cycle arrest and p21WAF1/CIP1 independent modulation of survivin in cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;319:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondo T, Minamino N, Nagamura-Inoue T, Matsumoto M, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. Identification and characterization of nucleophosmin/B23/numatrin which binds the anti-oncogenic transcription factor IRF-1 and manifests oncogenic activity. Oncogene. 1997;15:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang B, Hsu SH, Frankel W, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST. Stat3-mediated activation of microRNA-23a suppresses gluconeogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by down-regulating glucose-6-phosphatase and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha. Hepatology. 2012;56:186–197. doi: 10.1002/hep.25632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang N, Zhu M, Tsao SW, Man K, Zhang Z, Feng Y. MiR-23a-mediated inhibition of topoisomerase 1 expression potentiates cell response to etoposide in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:119. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong X, Coukos G, Zhang L. miRNAs in human cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;822:295–306. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-427-8_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan L, Zhou C, Lu Y, Hong M, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Chang Y, Zhang C, Li X. IFN-γ-mediated IRF1/miR-29b feedback loop suppresses colorectal cancer cell growth and metastasis by repressing IGF1. Cancer Lett. 2015;359:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Chen B, Feng M, Ouyang H, Zheng M, Ye Q, Nie Q, Zhang X. MicroRNA-23b promotes avian leukosis virus subgroup J (ALV-J) replication by targeting IRF1. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10294. doi: 10.1038/srep10294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao L, Zhang Y, Mo W, Yu Y, Lu H. BANF1is downregulated by IRF1-regulated microRNA-203 in cervical cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]