Abstract

Objective:

We investigated hypertension and diabetes mellitus in two management settings, namely cardiology and endocrinology, and their associations with albuminuria while accounting for the management of these two diseases.

Methods:

Our multicentre registry included patients (≥20 years) seen for hypertension in cardiology or for diabetes mellitus in endocrinology. We administered a questionnaire and measured blood pressure, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c and albuminuria.

Results:

Presence of both hypertension and diabetes was observed in 32.9% of hypertensive patients in cardiology (n = 1291) and 58.9% of diabetic patients in endocrinology (n = 1168). When both diseases were present, the use of combination antihypertensive therapy [odds ratio (OR) 0.31, P < 0.0001] and inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system (OR 0.66, P = 0.0009) was less frequent in endocrinology than cardiology, and the use of combination antidiabetic therapy (OR 0.16, P < 0.0001) was less frequent in cardiology than endocrinology. The control of hypertension and diabetes, however, was not different between the two management settings (P ≥ 0.21), regardless of the therapeutic target (SBP/DBP < 140/90 or 130/80 mmHg and glycosylated haemoglobin A1c <7.0 or 6.5%). The prevalence of albuminuria was higher (P ≤ 0.02) in the presence of both diseases (23.3%) than those with either hypertension (12.6%) or diabetes alone (15.9%).

Conclusion:

Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were often jointly present, especially in the setting of endocrinology. The management was insufficient on the use of combination antihypertensive therapy and inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system in endocrinology and for combination antidiabetic therapy in cardiology, indicating a need for more intensive management and better control of both clinical conditions.

Keywords: albuminuria, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, management, registry

INTRODUCTION

Current hypertension guidelines provide recommendations specifically for patients with diabetes mellitus, such as, for instance, intensive target of blood pressure (BP) control and initial use of inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system [1,2]. Current diabetes guidelines provide similar recommendations for the management of hypertension, although there is not much guidance on the management of diabetes mellitus in the presence of hypertension [3,4]. The presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus confers a higher risk of cardiovascular–renal disease than the presence of either condition alone [5]. In addition, the presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus makes the management of both diseases difficult and complicated [6]. In a recent Chinese registry, the control rate of hypertension in patients with both hypertension and diabetes mellitus was only 14.9%, being much lower than in those patients without diabetes mellitus (45.9%) [7]. In spite of low control rate of hypertension, physicians are often hesitating to add more antihypertensive drugs, such as diuretics [8], because of the concerns for side effects, such as hypokalaemia, and potential negative effects on insulin release.

In China, diabetes mellitus is managed by endocrine physicians and hypertension mainly by cardiovascular physicians. Although patients may move between the two departments and physicians may exchange ideas and views on the management of both diseases, comparative information is scarce. We therefore performed a multicentre registry across the two departments to investigate the prevalence and management of the presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus and the association of albuminuria with both diseases.

METHODS

Study design

The present study was designed as a cross-sectional, multicentre registry in China and carried out in the departments of cardiovascular and endocrine medicine of hospitals from June 2011 to March 2012. Both departments from the same hospital were encouraged to jointly participate in the study. However, one department from another hospital was also allowed to participate. We registered consecutive patients with previously diagnosed hypertension from the departments of cardiovascular medicine and patients with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus from the departments of endocrine medicine. The ethics committees of all participating hospitals approved the study protocol. All patients gave written informed consent.

To be eligible for inclusion, a patient had to be at least 20 years old, and was able to participate in two clinic visits 2–5 days apart. At the first clinic visit, physicians administered a standardized questionnaire to collect information on medical history, lifestyle and use of medications. BP and anthropometry were measured. At the second clinic visit, BP was recorded for the second time. Venous blood samples were drawn after overnight fasting for measurements of plasma glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin A1 (HbA1c) and serum lipids, and morning void urine samples were collected for urinary measurements. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed only in hypertensive patients without known diabetes mellitus.

We excluded from our study pregnant women, patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and patients participating in other clinical studies within the preceding 3 months.

Clinical and biochemical measurements

BP was measured using a validated Omron HEM-7201 automatic oscillometric BP monitor (Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) at the first and second clinic visits. On each of the two occasions, three BP readings were obtained in the seated position after the patients had rested for at least 5 min. These six readings were averaged for statistical analysis in all patients and for the diagnosis of hypertension in patients without known hypertension. If SBP was at least 140 mmHg or DBP at least 90 mmHg, hypertension was newly diagnosed. In the presence of previously diagnosed hypertension, treatment of hypertension was defined as the use of antihypertensive medication.

Plasma glucose concentration and serum lipids were measured. In patients without previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus, OGTT was performed for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, which was defined as a plasma glucose concentration of at least 7.0 mmol/l at fasting or 11.1 mmol/l 2 h after ingestion of 75 g of glucose dissolved in water. In previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus, treatment of diabetes mellitus was defined as the current use of oral antidiabetic drugs and/or insulin.

Anthropometric measurements included body weight, body height and waist and hip circumferences. BMI was calculated as the body weight in kilograms divided by the body height in metres squared. Urinary routine test was performed on fresh urine samples using automatic devices at the laboratory of each participating hospitals. Urinary albumin and creatinine excretions were measured using the immunochemical method in a core laboratory certified by the College of American Pathologists (www.cap.org). In the absence of apparent urological infections on urine samples, microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria were defined as a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio in the range from 30 to 299 mg/g and more than 300 mg/g, respectively. Albuminuria included both microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria.

Definitions

Obesity and overweight were defined as a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater. Dyslipidemia was defined as a serum triglycerides concentration of 1.70 mmol/l or higher, a serum total cholesterol concentration of 5.18 mmol/l or higher, a serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentration of 3.37 mmol/l or higher, or a serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentration of 1.04 mmol/l or lower or as the use of statin or other lipid-lowering agents [9]. The metabolic syndrome was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) – Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) IV criteria for Asians [10]. Ischaemic heart disease included myocardial infarction and angina. Myocardial infarction and stroke were self-reported.

Statistical methods

For database management and statistical analysis, we used SAS software (version 9.13; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Means and proportions were compared by the Student's t test and the Fisher's exact test, respectively. Continuous measurements with a skewed distribution were normalized by logarithmic transformation and represented by geometric mean and 95% confidence interval (CI). Logistic regression analyses were performed to study the associations of interest.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study participants

Of the 2510 enrolled study participants, 51 were excluded from the present analysis because of missing information on HbA1c, leaving 2459 patients included in the present analysis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 1291 and 1168 study participants, respectively, recruited from cardiology and endocrinology departments. Hypertensive patients from cardiology and diabetic patients from endocrinology were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) different in age, SBP and DBP, pulse rate, plasma fasting glucose, HbA1c, serum total cholesterol and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, ischaemic heart disease, myocardial infarction and stoke, but not (P ≥ 0.14) in sex distribution, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, current smoking and alcohol intake, serum concentrations of triglycerides and HDL and LDL cholesterol, or the prevalence of obesity, overweight and dyslipidemia.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Cardiology (n = 1291) | Endocrinology (n = 1168) | P value |

| Men, n (%) | 589 (45.6) | 564 (48.3) | 0.20 |

| Age (years) | 58.8 ± 11.5 | 57.7 ± 11.6 | 0.03 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 3.3 | 25.2 ± 3.4 | 0.17 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.89 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 215 (16.7) | 208 (17.8) | 0.45 |

| Alcohol intake, n (%) | 212 (16.4) | 197 (16.9) | 0.79 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 141.4 ± 16.9 | 132.3 ± 17.0 | <0.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83.2 ± 12.2 | 77.1 ± 9.8 | <0.0001 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | 72.6 ± 13.2 | 74.8 ± 12.5 | <0.0001 |

| Plasma fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 5.83 (5.76–5.91) | 7.86 (7.72–8.01) | <0.0001 |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.15 ± 0.99 | 7.57 ± 1.77 | <0.0001 |

| Serum triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.43 (1.39–1.47) | 1.45 (1.39–1.50) | 0.48 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.81 ± 1.09 | 4.90 ± 1.15 | 0.03 |

| Serum HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.30 ± 0.34 | 1.31 ± 0.38 | 0.31 |

| Serum LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.88 ± 0.92 | 2.91 ± 0.93 | 0.43 |

| Obesity and overweight, n (%) | 666 (51.6) | 567 (48.5) | 0.14 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 950 (73.6) | 830 (71.1) | 0.18 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 408 (31.6) | 431 (36.9) | 0.006 |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 223 (17.3) | 84 (7.2) | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 54 (4.2) | 12 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 82 (6.4) | 53 (4.5) | 0.05 |

Values are arithmetic (±SD) or geometric mean (95% confidence interval) or number of patients (%). For definitions of obesity and overweight, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction and stroke, see the METHODS section. HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus was observed in 32.9% of hypertensive patients seen in cardiology, 58.9% of diabetic patients seen in endocrinology and 45.3% of patients seen in both departments (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of the common presence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in hypertensive patients in cardiology, diabetic patients in endocrinology or patients in both departments. The prevalence is given above the bar graph with the number of subjects in the parentheses. The P value for the comparison between cardiology and endocrinology is also given.

Management of hypertension

Table 2 shows the status of management of hypertension in patients with hypertension alone (n = 866) and those with the presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus from cardiology (n = 425) and endocrinology (n = 688), respectively.

TABLE 2.

Management of hypertension

| Hypertension alone | Presence of hypertension and diabetes | ||

| Cardiology (n = 866) | Cardiology (n = 425) | Endocrinology (n = 688) | |

| BP (mmHg) | |||

| SBP | 140.7 ± 16.7 | 142.8 ± 17.2 | 139.8 ± 16.8b |

| DBP | 83.8 ± 12.1 | 82.0 ± 12.3 | 79.2 ± 10.4a,b |

| Treated, n (%) | 746 (86.1) | 391 (92.0)a | 533 (77.5)a,b |

| Monotherapy | 366 (42.3) | 172 (40.5) | 360 (52.3)b |

| Combination therapy | 380 (43.9) | 219 (51.5)a | 173 (25.1)a,b |

| Use of ACE inhibitors or AT1 blockers | 378 (43.6) | 242 (56.9)a | 321 (46.7)b |

| Controlled, n (%) | |||

| SBP/DBP <140/90 mmHg | 348 (40.2) | 163 (38.3) | 285 (41.4) |

| SBP/DBP <130/80 mmHg | 130 (15.0) | 61 (14.4) | 119 (17.3) |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AT1, angiotensin type 1 receptor; BP, blood pressure.

aP ≤ 0.05 versus patients with hypertension alone.

bP ≤ 0.05 versus patients recruited from cardiology.

When both hypertension and diabetes mellitus were present, the use of combination antihypertensive therapy [25.1 versus 51.5%, odds ratio (OR) 0.31, 95% CI 0.24–0.41; P < 0.0001] and inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system (46.7 versus 56.9%, OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.52–0.84; P = 0.0009) was significantly less frequent in endocrinology than cardiology.

Nevertheless, the control rate was not significantly different (P ≥ 0.21) between cardiology and endocrinology settings and between patients with both hypertension and diabetes mellitus and patients with hypertension alone (P ≥ 0.49), regardless of the definition of target BP (<140/90 or <130/80 mmHg).

Management of diabetes mellitus

Table 3 shows the status of management of diabetes mellitus in patients with diabetes mellitus alone (n = 480) and those with both diabetes mellitus and hypertension from endocrinology (n = 688) and cardiology (n = 425), respectively.

TABLE 3.

Management of diabetes mellitus

| Diabetes alone | Presence of diabetes and hypertension | ||

| Endocrinology (n = 480) | Endocrinology (n = 688) | Cardiology (n = 425) | |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 8.00 (7.76–8.24) | 7.77 (7.59–7.96) | 7.01 (6.83–7.20)a,b |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 ± 1.9 | 7.6 ± 1.7 | 6.9 ± 1.3a,b |

| Treated, n (%) | 429 (89.4) | 631 (91.7) | 288 (67.8)a,b |

| Oral antidiabetic drugs alone | 271 (56.5) | 384 (55.8) | 219 (51.5) |

| Insulin alone | 69 (14.4) | 96 (14.0) | 49 (11.5) |

| Oral antidiabetic drugs plus insulin | 89 (18.5) | 146 (21.2) | 18 (4.2)a,b |

| Controlled, n (%) | |||

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 215 (44.8) | 291 (42.3) | 165 (38.8) |

| HbA1c < 6.5% | 140 (29.2) | 178 (25.9) | 117 (27.5) |

HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c.

aP ≤ 0.05 versus patients with diabetes mellitus alone.

bP ≤ 0.05 versus patients recruited from endocrinology departments.

When both diabetes mellitus and hypertension were present, the combination of oral antidiabetic agents and insulin was significantly less frequently used in cardiology than endocrinology (4.2 versus 21.2%, OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.10–0.27; P < 0.0001).

The control rate was not different between cardiology and endocrinology (P ≥ 0.26) and between patients with both diabetes mellitus and hypertension and patients with diabetes mellitus alone (P ≥ 0.17), regardless of the definition of target glucose control (HbA1c < 7.0 or 6.5%).

Association of albuminuria with hypertension and diabetes mellitus

The prevalence of albuminuria was significantly (P ≤ 0.02) higher in patients with both hypertension and diabetes mellitus (23.3%, n = 652) than in patients with either hypertension (12.6%, n = 613) or diabetes mellitus alone (15.9%, n = 232). The OR of albuminuria was 2.12 (95% CI: 1.57–2.86, P < 0.0001) and 1.60 (95% CI: 1.08–2.38, P = 0.02) for the presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus versus either hypertension or diabetes mellitus alone, respectively.

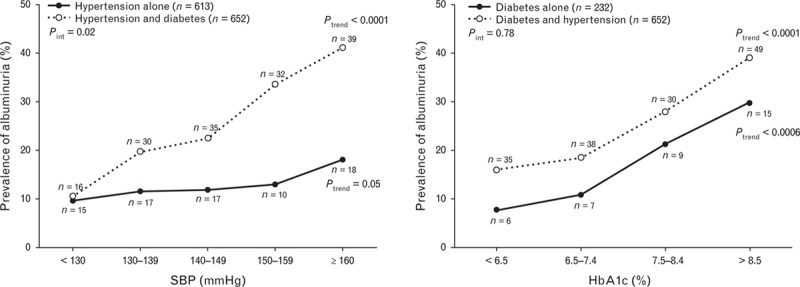

There was significant interaction between the presence of diabetes mellitus and SBP (P value for interaction, 0.02), but not HbA1c (P value for interaction, 0.78), in relation to the prevalence of albuminuria (Fig. 2). The presence of diabetes mellitus significantly enhanced the association with SBP, whereas the presence of hypertension increased the risk of albuminuria at all levels of HbA1c.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of albuminuria in relation to SBP (a) and plasma glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c, b) in patients with either (dot) or both diseases (circle). The number of subjects is given in the parentheses. The P values for trend and interaction between the presence of diabetes mellitus and SBP or between the presence of hypertension and glycosylated haemoglobin A1c are also given.

DISCUSSION

The key findings of our multicentre registry are three-fold. First, the prevalence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus was high, especially in the setting of endocrinology. About a third of hypertensive patients in cardiology had diabetes mellitus, and two-thirds of diabetic patients in endocrinology had hypertension. Second, the main differences on the management of hypertension and diabetes mellitus between endocrinology and cardiology lied in the less-frequent use of combination therapy for hypertension in endocrinology and for diabetes mellitus in cardiology. Inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system, though recommended as initial or indispensable therapy by most guidelines for the management of hypertension in diabetes mellitus [1–4], were also less frequently used in endocrinology than cardiology. Third, the presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus was associated with a higher risk of albuminuria, especially in uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes mellitus. In the presence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, control of both disease conditions was not sufficient, probably because treatment was not sufficient in either setting.

The immediate clinical implication of our finding is that physicians should intensify treatment to achieve better control of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for the prevention of target organ damage. Because of apparent divergence of treatment intensity between settings, whether a common platform for both disease conditions would improve the management should be investigated.

There are several possible explanations for the low treatment intensity of hypertension in the setting of endocrinology and of diabetes mellitus in the setting of cardiology. First, low awareness may be the main contributing factor for most patients were left untreated. Second, patients have to be referred to specialists for the combination therapy of antihypertensive and antidiabetic therapy. That to some extent may explain the under use of combination therapy. Similar explanation may also apply for the under use of inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system for hypertension in endocrinology. Third, hypertension in the setting of endocrinology and diabetes mellitus in the setting of cardiology might be relatively mild and therefore require less treatment. BP was indeed slightly lower in hypertensive patients in endocrinology than cardiology. Plasma glucose and HbA1c were lower in diabetic patients in cardiology than endocrinology.

Our observation on the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus is in line with the results of previous studies in China [7,11] and other countries [5,12–21]. The presence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus ranged from 17.3 [12] to 37.2% [7] in hypertension [7,11–15] and from 39.6 [5] to 74.4% [21] in diabetes mellitus [5,16–21]. When our data and previous studies are taken together, these two disease conditions are apparently often jointly present, especially in the setting of care for diabetes mellitus.

Our observation on the interaction between the presence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus and the level of SBP in relation to albuminuria indicated that in diabetic patients, hypertension may require more intensive BP control, for example to a level of 130/80 mmHg or lower, instead of 140/90 mmHg, as recommended in several guidelines on hypertension [1,2] or diabetes mellitus [3,4]. Our finding provided further evidence for these recommendations, although several recent guidelines amended their recommendations on the target of BP control in diabetes mellitus [22–24] on the basis of the evidence from a recently published trial [25]. This controversial issue requires more and careful research.

Our study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, our study had a cross-sectional design and does not allow any causal inference. Second, albuminuria was evaluated on a single spot urine sampling. However, albuminuria and creatinine were measured in a core laboratory. A stringent quality assurance programme was implemented, including the exclusion of patients with a suspected urinary tract infection. Third, plasma HbA1c and glucose were measured in each of the participating hospitals. However, after accounting for study site, our results remained unaltered (data not shown).

In conclusion, hypertension and diabetes mellitus were often jointly present, especially in the setting of endocrinology. The management of these clinical conditions was insufficient, particularly on the use of combination antihypertensive therapy and inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system in endocrinology and for combination antidiabetic therapy in cardiology, indicating a need for more intensive management and better control of both clinical conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The registry was funded by Sanofi China (Shanghai). The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation of the patients and the contribution of the investigators. The participating hospitals were listed in the alphabetical order of province and hospital, with departments, principal investigators and the number of enrolled patients in the parentheses in an online supplemental Appendix 1.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Reviewers’ Summary Evaluations

Reviewer 1

This was an observational study on clinical practice in China regarding characteristics and drug treatment profile of patients with hypertension and diabetes at hospital departments in China. The use of a national register is a benefit. Some shortcomings in clinical practice were noticed, for example the underuse of drug combination treatment in these patients. This report is a step forward when real world data from registers are used for benchmarking and improvements of clinical care. Ideally also data from patients treated in primary healthcare could be added in the future, as most such patients are followed outside hospitals.

Reviewer 3

The novelty from this paper lies in comparing the management of co-existing type 2 diabetes and hypertension in cardiology clinics and in diabetes clinics in major regional centres in China, providing interesting insights into clear differences that exist.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ATP, Adult Treatment Panel; CI, confidence interval; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; NCEP, National Cholesterol Education Program; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; OR, odds ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, et al. Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res 2014; 37:253–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu LS. Writing Group of 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin J Cardiol 2011; 39:579–615.(Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Diabetes Federation Guideline Development Group. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Prac 2014; 104:1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinese Diabetes Society. China guideline for type 2 diabetes. Chin J Diabetes Mellitus 2014; 6:447–498.(Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Hypertension in Diabetes Study Group. Hypertension in Diabetes Study (HDS): II. Increased risk of cardiovascular complications in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients. J Hypertens 1993; 11:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borzecki AM, Berlowitz DR. Management of hypertension and diabetes: treatment goals, drug choices, current practice, and strategies for improving care. Curr Hypertens Rep 2005; 7:439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu DY, Liu LS, Yu JM, Yao CH. National survey of blood pressure control rate in Chinese hypertensive outpatients-China STATUS. Chin J Cardiol 2010; 38:230–238.(Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong MC, Tam WW, Cheung CS, Tong EL, Sek AC, Cheung NT, et al. Antihypertensive prescriptions over a 10-year period in a large Chinese population. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26:931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Committee for Developing Chinese Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Adults. Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults. Chin J Cardiol 2007; 35:390–419.(Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129 Suppl 2:S1–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Zhao D, Liu J, Qi Y, Sun J, Wang W. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in outpatients with essential hypertension in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013; 3:e003798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonati C, Morganti A, Comarella L, Mancia G, Zanchetti A. IPERDIA Study Group. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes among patients with hypertension under the care of 30 Italian clinics of hypertension: results of the (Iper)tensione and (dia)bete study. J Hypertens 2008; 26:1801–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan BM, Li J, Hutchison FN, Ferdinand KC. Hypertension in the United States, 1999 to 2012: progress toward healthy people 2020 goals. Circulation 2014; 130:1692–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Puig J, Ruilope LM, Luque M, Fernández J, Ortega R, Dal-Ré R. AVANT Study Group Investigators. Glucose metabolism in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Med 2006; 119:318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjeldsen SE, Naditch-Brule L, Perlini S, Zidek W, Farsang C. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in uncontrolled hypertension across Europe: the Global Cardiometabolic Risk Profile in Patients with hypertension disease survey. J Hypertens 2008; 26:2064–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko SH, Kwon HS, Song KH, Ahn YB, Yoon KH, Yim HW, et al. Long-term changes of the prevalence and control rate of hypertension among Korean adults with diagnosed diabetes: 1998–2008 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 97:151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baskar V, Kamalakannan D, Holland MR, Singh BM. The prevalence of hypertension and utilization of antihypertensive therapy in a district diabetes population. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:2107–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gee ME, Janssen I, Pickett W, McAlister FA, Bancej CM, Joffres M, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among Canadian adults with diabetes, 2007 to 2009. Can J Cardiol 2012; 28:367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suh DC, Kim CM, Choi IS, Plauschinat CA, Barone JA. Trends in blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988–2004. J Hypertens 2009; 27:1908–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez-Fernandez R, Mariño AF, Cadarso-Suarez C, Botana MA, Tome MA, Solache I, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Galicia (Spain) and association with related diseases. J Hum Hypertens 2007; 21:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comaschi M, Coscelli C, Cucinotta D, Malini P, Manzato E, Nicolucci A. SFIDA Study Group-Italian Association of Diabetologists (AMD). Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic subjects attending outpatient clinics in Italy the SFIDA (survey of risk factors in Italian diabetic subjects by AMD) study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2005; 15:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014; 311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. Task Force Members. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2013; 31:1281–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2013. Diabetes Care 2013; 36 Suppl 1:S11–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Grimm RH, Jr, Cutler JA, et al. ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1575–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.