Abstract

Background

In 2012, more than 400,000 urinary bladder cancer cases occurred worldwide, making it the 7th most common type of cancer. Although many previous studies focused on the relationship between diet and bladder cancer, the evidence related to specific food items or nutrients that could be involved in the development of bladder cancer remains inconclusive. Dietary components can either be, or be activated into, potential carcinogens through metabolism, or act to prevent carcinogen damage.

Methods/design

The BLadder cancer, Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants (BLEND) study was set up with the purpose of collecting individual patient data from observational studies on diet and bladder cancer. In total, data from 11,261 bladder cancer cases and 675,532 non-cases from 18 case–control and 6 cohort studies from all over the world were included with the aim to investigate the association between individual food items, nutrients and dietary patterns and risk of developing bladder cancer.

Discussion

The substantial number of cases included in this study will enable us to provide evidence with large statistical power, for dietary recommendations on the prevention of bladder cancer.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Diet, Risk, Pooled analysis

Background

In 2012, more than 400,000 urinary bladder cancer (UBC) cases occurred worldwide, making it the 7th most common type of cancer [1]. Due to lifetime ongoing cystoscopies and recurrent treatment episodes, UBC is the most expensive malignancy in terms of healthcare expenditure in the USA and in most Western countries [2, 3]. The effect of diet in the prevention of UBC could be more pronounced compared to other types of cancer as dietary components are often excreted through the urine. Dietary components can either be, or be activated into, potential carcinogens through metabolism, or act to prevent carcinogen damage [4].

Although many previous studies focused on the relationship between diet and UBC, the evidence related to specific food items or nutrients that could be involved in the development of UBC remains inconclusive. The World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) concluded in their most recent WCRF/AICR expert report [5] that there is some evidence for an decreased risk of bladder cancer with greater consumption of vegetables, fruit and tea and strong evidence that drinking water containing arsenic increases the risk of bladder cancer. A potential reason for the absence of evidence between specific foods and nutrients and the risk of UBC is that associations between cancer risk and dietary intake are usually weak and most previous studies may have had insufficient sample size and thus missed adequate statistical power for detailed analyses on individual food items, for subgroup analyses and for food-food interactions. Pooling of individual data of existing epidemiological studies on diet and UBC might therefore be an effective way to increase the current knowledge on the influences of foods, nutrients and dietary patterns on UBC risk. The influence of occupational risk and pollutants in the water, such as arsenic, are not part of this investigation. Occupational risk factors were identified as risk factors for bladder cancer [6]. However, as the frequency of having a high-risk occupation is very low (<3 %) this could not importantly confound the results. For this reason, the BLEND study as well as most previous bladder cancer epidemiological studies have not corrected for occupation in their analyses.

Within the BLadder cancer, Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants (BLEND) study, we aim to investigate comprehensively the association between individual food items, nutrients, and dietary patterns and risk of developing UBC. The results of this study will likely aid in developing and reviewing current dietary recommendations for the prevention of UBC. In this paper we report on the methodology and baseline characteristics of the BLEND study.

Methods/design

Included epidemiological studies

Possible eligible epidemiological studies reporting on diet and UBC have been identified by a computerized search of Medline (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland) (1966-Sept 2009), and Embase (Elsevier B. V., Amderstam, the Netherlands (1974-Sept 2009) using the medical subject headings (MeSH; National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland) “urinary bladder neoplasms” and “risk” and the free-text word “risk”. The search was restricted to the MeSH term “humans”. All articles from peer-reviewed journals, reporting on the association between diet and risk of UBC were selected. Within these articles, we identified the eligible studies that used a case–control or a cohort design, had data on diet and a minimum number of cases of 40 patients. The principal investigators of these eligible studies were contacted and invited to participate in our collaborative project. There was no restriction about the amount of available diet items, however, data on confounders, especially, smoking, had to be available.

Data harmonization

To harmonize our data, a common codebook was created based on the Eurocode 2 Core classification version 99/2 [7]. The Eurocode 2 Food Coding System was originally developed to serve as a standard instrument for nutritional surveys in Europe and to serve the need for food intake comparisons within the European FLAIR Eurofoods-Enfant Project [8]. The Eurocode 2 classification System unambiguously defines which types of food are covered or not within each food category so that the potential for misclassification is limited. The System provides coding for food items consumed all over the world. Coding has been done centrally by the researchers of the Blend team. One part of the team did the coding, while the other part of the team checked for possible errors. Translation of the questionnaires in English was provided by the principle investigator for studies in other languages. Apart from the variables on diet, we collected non-dietary data such as, study design, age, gender, ethnic group, TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors (TNM), smoking status, smoking frequency and duration, and family history. Each participant was assigned a random and unique identification number. Analyses were restricted to adults, i.e. participants younger than 18 years were excluded. Categorical data have been checked by producing frequency tables to identify inaccurate coding while continuous data have been checked performing descriptive statistics. Possible coding errors and missing data within the provided data of each study were discussed with the principal investigator and updated accordingly. Outliers, defined as values outside the general distribution of the data, were identified after visual inspection of the resultant scatterplots and omitted [9].

Baseline characteristics

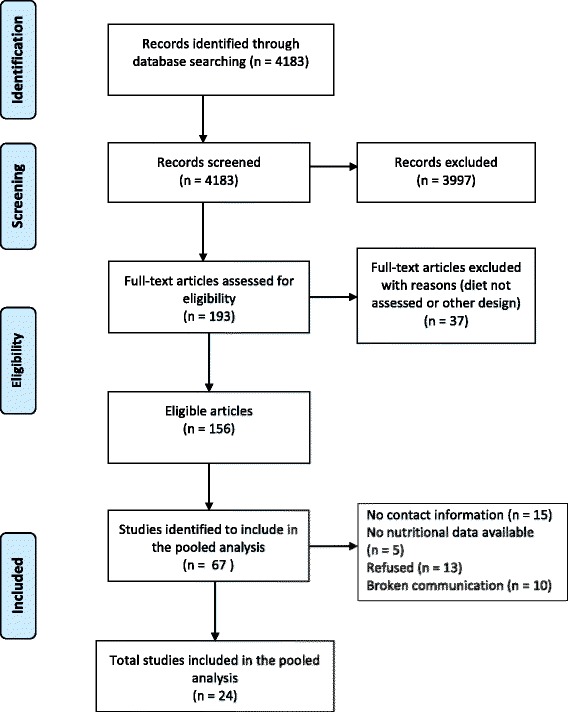

In total 67 potentially eligible studies from 156 retrieved articles were identified (Fig. 1). Thirty-eight investigators agreed to participate and 24 [10–34] provided data (Table 1). Reasons for non-participation after initially agreement were: no data on diet or the minimum set of confounders available, the workload that was already too high and the wish to publish the results on nutrition first before participating in a pooled study. With some investigators, we lost communication after initial contact. The first datasets and codebooks were collected in March 2009 while the last dataset was included in March 2016. Another two new studies, one case–control and one cohort study are available for inclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the Bladder cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants study (BLEND)

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the pooled analysis of the Bladder cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants study (BLEND)

| Study | Country | Recruitment period |

Study design | Cases N |

Controls N |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| men | women | total | men | women | total | ||||

| Case–control studies | |||||||||

| Los-Angeles bladder cancer Case–control study [10] | USA | 1987–1999 | Population based case–control | 1,307 | 353 | 1,660 | 1,237 | 349 | 1,586 |

| Roswell Park Cancer Institute [11] | USA | 1982–1998 | Hospital-based case–control | 164 | 53 | 217 | 501 | 163 | 664 |

| Belgian Case–control study on bladder cancer [12] | Belgium | 1999–2004 | Population based case–control | 172 | 28 | 200 | 228 | 156 | 384 |

| Aichi Prefecture Case–control study [13] | Japan | 1996–1999 | Hospital-based case–control | 245 | 58 | 303 | 244 | 59 | 303 |

| Kaohsiung [14] | Taiwan | 1996–1997 | Hospital-based case–control | 31 | 9 | 40 | 124 | 36 | 160 |

| Hessen Case–control study on bladder cancer [15] | Germany | 1989–1992 | Hospital-based case–control | 239 | 61 | 300 | 239 | 61 | 300 |

| Stockholm Case–control study [16] | Sweden | 1985–1987 | Population based case–control | 204 | 67 | 271 | 281 | 268 | 549 |

| Roswell Park Memorial Institute Case–control study on bladder cancer [17] | USA | 1957–1965 | Hospital-based case–control | 415 | 138 | 553 | 3,253 | 4,636 | 7,889 |

| Reina Sofia University Hospital [18] | Spain | 1997 | Hospital-based case–control | 74 | 11 | 85 | 89 | 41 | 130 |

| New Hampshire bladder cancer study [19] | USA | 1994–2001 | Population based case–control | 286 | 104 | 390 | 185 | 138 | 323 |

| Italian Case–control study on bladder cancer [20] | Italy | 1985–1993 | Hospital-based case–control | 617 | 110 | 727 | 766 | 298 | 1,064 |

| Brescia bladder cancer study [21] | Italy | 1997–2000 | Hospital-based case–control | 200 | 0 | 200 | 214 | 0 | 214 |

| Dortmund Hörde study [22] | Germany | 2009–2010 | Hospital based case–control | 145 | 48 | 193 | 177 | 56 | 233 |

| National Enhanced Cancer Surveillance System (NESCC) [23] | Canada | 1994–1997 | Population based case–control | 600 | 311 | 911 | 2,451 | 2,423 | 4,874 |

| French INSERM study [24] | France | 1984–1987 | Hospital-based case–control | 166 | 33 | 199 | 275 | 47 | 322 |

| South and East China Case–control study on bladder and prostate cancer [25] | China | 2005–2008 | Hospital-based case–control | 390 | 93 | 483 | 364 | 100 | 464 |

| Molecular Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer and Prostate Cancer [26] | USA | 1993–1997 | Hospital-based case–control | 149 | 45 | 194 | 243 | 58 | 301 |

| North Carolina case control study [27] | USA | 1987–1991 | Hospital-based case–control | 188 | 56 | 244 | 174 | 41 | 215 |

| Cohort studies | |||||||||

| Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC) & the Cohort of Swedish Men [28] | Sweden | 1987–1990 | Population based cohort | 538 | 119 | 657 | 2,188 | 484 | 2,672 |

| Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer [29] | The Netherlands | 1986–2003 | Population based cohort | 779 | 161 | 940 | 2,273 | 2,419 | 4,692 |

| Women's Lifestyle and Health Study [30] | Norway, Sweden | 1991–2006 | Population based cohort | 0 | 49 | 49 | 0 | 48,942 | 48,942 |

| RERF atomic bomb survivors Study [31] | Japan | 1950–2000 | Population based cohort | 216 | 85 | 301 | 19,362 | 28,249 | 47,611 |

| VITamins and Lifestyle Study (VITAL) [32] | USA | 2000–2008 | Population based cohort | 338 | 106 | 444 | 36,454 | 39,983 | 76,437 |

| European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) [33, 34] | Europe | 1993–2006 | Population based cohort | 1,227 | 525 | 1,752 | 141,872 | 333,279 | 475,151 |

| TOTAL | – | – | – | 8,657 | 2,604 | 11,313 | 213,227 | 462,305 | 675,480 |

More than 2/3 of the case–control studies [11, 13–15, 17, 18, 20–22, 24–27] had a hospital-based case–control design. Ten studies [12, 16, 19–21, 24–28] were also part of the International Bladder Cancer Consortium that was formed in 2005 as an open scientific forum for genetic-epidemiologic researchers in the field of UBC. Most of the studies [12, 15, 16, 18, 20–22, 24, 28–30, 33, 34] were from Europe, eight studies [10, 11, 17, 19, 23, 26, 27, 32] were from the USA and Canada, and four [13, 14, 25, 31] studies were from Asia.

After excluding participants with unknown age (n = 5), unknown case–control status (n = 214) and unknown smoking status (n = 14,028) data of 686,793 participants were available for analyses of which 11,261 cases and 675,532 non-cases. The Brescia bladder cancer study [21] contained only male participants, while the Women’s Lifestyle and Health study consisted of only female participants. Most of the cases were from America to Europe while only 10 % were from Asia.

The cases of the European and Asian case–control studies had the highest male/female ratio (4:1) while their overall male/female ratio was 3:1 (Table 2). In general, controls were younger than cases, 57.0 versus 61.6 years and 51.8 versus 61.1 years, respectively for case–control studies and cohort studies with an exception for the Asian case–control studies (66.1 versus 64.9 years). Most of the participants were Caucasian, whereas only 10 % of the cases were Asian. In contrast with Asia, where one third of the cases were never smoker, only one fifth of the cases never smoked in Europe and USA. Overall, 40 % of the cases were smokers. Controls had significant less current and more never smokers than cases. For cohort studies, nearly half of the controls never smoked. Staging was not reported in 60 and 70 % respectively for the case–control and cohort studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population of the Bladder cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants study (BLEND)

| Total | Europe | America | Asia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |||||||||

| N | (() | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Case–control studies | ||||||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 5,592 | (77.9) | 11,045 | (55.9) | 1,817 | (83.5) | 2,269 | (71.0) | 3,109 | (74.6) | 8,044 | (50.7) | 666 | (80.6) | 732 | (79.0) |

| Female | 1,578 | (22.1) | 8,930 | (44.1) | 358 | (16.5) | 927 | (29.0) | 1,060 | (25.4) | 7,808 | (49.3) | 160 | (19.4) | 195 | (21.0) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 61.6 | (11.4) | 57.0 | (14.4) | 65.4 | (9.7) | 63.3 | (10.9) | 59.0 | (11.1) | 55.3 | (14.5) | 64.9 | (13.1) | 66.1 | (12.2) |

| < 50 | 961 | (13.4) | 5,665 | (28.4) | 135 | (6.2) | 308 | (9.6) | 723 | (17.3) | 5,271 | (33.3) | 103 | (12.5) | 86 | (9.3) |

| 50– 59 | 1,832 | (25.6) | 4,501 | (22.5) | 407 | (18.7) | 787 | (24.6) | 1,261 | (30.2) | 3,549 | (22.4) | 164 | (19.9) | 165 | (17.8) |

| 60–64 | 1,399 | (19.5) | 2,772 | (13.9) | 381 | (17.5) | 555 | (17.4) | 929 | (22.3) | 2,1 | (13.2) | 89 | (10.8) | 117 | (12.6) |

| 65–69 | 1,122 | (15.6) | 2,842 | (14.2) | 482 | (22.2) | 567 | (17.7) | 522 | (12.5) | 2,138 | (13.5) | 118 | (14.3) | 137 | (14.8) |

| ≥ 70 | 1,856 | (25.9) | 4,195 | (21.0) | 770 | (35.4) | 979 | (30.6) | 734 | (17.6) | 2,794 | (17.6) | 352 | (42.6) | 422 | (45.5) |

| Ethnic group | ||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 4,438 | (61.9) | 15,057 | (75.4) | 593 | (27.3) | 831 | (26.0) | 3,845 | (92.2) | 14,226 | (89.2) | 782 | (94.7) | 767 | (82.7) |

| Mixed | 9 | (0.1) | 10 | (0.1) | – | – | – | – | 9 | (0.2) | 10 | (0.1) | – | – | – | – |

| Asian | 788 | (11.0) | 895 | (4.5) | – | – | – | – | 6 | (0.1) | 128 | (0.8) | – | – | – | – |

| Black | 52 | (0.7) | 748 | (3.7) | – | – | – | – | 52 | (1.2) | 748 | (4.7) | – | – | – | – |

| Any other ethnic group | 64 | (0.9) | 232 | (1.2) | – | – | – | – | 21 | (0.5) | 72 | (0.5) | 43 | (5.2) | 160 | (17.3) |

| Unknown | 1,819 | (25.4) | 3,033 | (15.2) | 1,582 | (72.7) | 2,365 | (74.0) | 236 | (5.7) | 668 | (4.2) | 1 | (0.1) | – | – |

| Tobacco smoking status | ||||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 2,95 | (41.1) | 6,98 | (34.9) | 1,038 | (47.7) | 1,022 | (32.0) | 1,564 | (37.5) | 5,695 | (35.9) | 348 | (42.1) | 263 | (28.4) |

| Former smoker | 2,703 | (37.7) | 5,269 | (26.4) | 747 | (34.3) | 1,025 | (32.1) | 1,731 | (41.5) | 3,943 | (24.9) | 225 | (27.2) | 301 | (32.5) |

| Never smoker | 1,517 | (21.2) | 7,726 | (38.7) | 390 | (17.9) | 1,149 | (36.0) | 874 | (21.0) | 6,214 | (39.2) | 253 | (30.6) | 363 | (39.2) |

| Staging | ||||||||||||||||

| Non–invasive | 2,246 | (31.3) | – | – | 511 | (23.5) | – | – | 1,606 | (38.5) | – | – | 129 | (15.6) | – | – |

| Invasive | 609 | (8.5) | – | – | 73 | (3.4) | – | – | 366 | (8.8) | – | – | 170 | (20.6) | – | – |

| Unknown | 4,315 | (60.2) | – | – | 1,591 | (73.1) | – | – | 2,197 | (52.7) | – | – | 527 | (63.8) | – | – |

| Continent | ||||||||||||||||

| Europe | 2,175 | (30.3) | 3,196 | (16.0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| America | 4,169 | (58.1) | 15,852 | (79.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Asia | 826 | (11.5) | 927 | (4.6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cohort studies | ||||||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 2,866 | (69.2) | 205,678 | (31.4) | 2,544 | (74.9) | 146,333 | (27.5) | 338 | (76.1) | 39,983 | (52.3) | 216 | (71.8) | 19,362 | (40.7) |

| Female | 1,277 | (30.8) | 449,827 | (68.6) | 854 | (25.1) | 385,124 | (72.5) | 106 | (23.9) | 36,454 | (47.7) | 85 | (28.2) | 28,249 | (59.3) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 61.1 | (8.5) | 51.8 | (10.8) | 60.9 | (7.9) | 50.4 | (10.2) | 66.4 | (6.4) | 61.4 | (7.4) | 55.7 | (12.0) | 52.0 | (13.6) |

| < 50 | 380 | (9.2) | 270,949 | (41.3) | 277 | (8.2) | 249,151 | (46.9) | – | – | – | – | 103 | (34.2) | 21,798 | (45.8) |

| 50–59 | 1,305 | (31.5) | 232,316 | (35.4) | 1,154 | (34.0) | 184,999 | (34.8) | 69 | (15.5) | 35,193 | (46.0) | 82 | (27.2) | 12,124 | (25.5) |

| 60–64 | 1,114 | (26.9) | 81,842 | (12.5) | 974 | (28.7) | 62,868 | (11.8) | 92 | (20.7) | 13,923 | (18.2) | 48 | (15.9) | 5,051 | (10.6) |

| 65–69 | 757 | (18.3) | 39,082 | (6.0) | 610 | (18.0) | 22,425 | (4.2) | 109 | (24.5) | 12,561 | (16.4) | 38 | (12.6) | 4,096 | (8.6) |

| ≥ 70 | 587 | (14.2) | 31,316 | (4.8) | 383 | (11.3) | 12,014 | (2.3) | 174 | (39.2) | 14,760 | (19.3) | 30 | (10.0) | 4,542 | (9.5) |

| Ethnic group | ||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 3,815 | (92.1) | 602,416 | (91.9) | 3,398 | (100) | 531,457 | (100) | 417 | (93.9) | 70,959 | (92.8) | – | – | – | – |

| Asian | 314 | (7.6) | 50,651 | (7.7) | – | – | – | – | 13 | (2.9) | 3,04 | (4.0) | 301 | (100) | 47,611 | (100) |

| Black | 7 | (0.2) | 969 | (0.1) | – | – | – | – | 7 | (1.6) | 969 | 1.3) | – | – | – | – |

| Any other ethnic group | 1 | (0.0) | 475 | (0.1) | – | – | – | – | 1 | (0.2) | 475 | (0.6) | – | – | – | – |

| Unknown | 6 | (0.1) | 994 | (0.2) | – | – | – | – | 6 | (1.4) | 994 | (1.3) | – | – | – | – |

| Tobacco smoking status | ||||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 1,677 | (40.5) | 156,467 | (23.9) | 1,418 | (41.7) | 130,871 | (24.6) | 61 | (13.7) | 6,411 | (8.4) | 198 | (65.8) | 19,185 | (40.3) |

| Former smoker | 1,594 | (38.5) | 185,006 | (28.2) | 1,296 | (38.1) | 149,472 | (28.1) | 280 | (63.1) | 33,651 | (44.0) | 18 | (6.0) | 1,883 | (4.0) |

| Never smoker | 872 | (21.0) | 314,032 | (47.9) | 684 | (20.1) | 251,114 | (47.3) | 103 | (23.2) | 36,375 | 47.6) | 85 | (28.2) | 26,543 | (55.7) |

| Staging | ||||||||||||||||

| Non–invasive | 1,196 | (28.9) | – | – | 1,196 | (35.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Invasive | 661 | (16.0) | – | – | 661 | (19.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Unknown | 2,286 | (55.2) | – | – | 1,541 | (45.4) | – | – | 444 | (100) | – | – | 301 | (100) | – | – |

| Continent | ||||||||||||||||

| Europe | 3,398 | (82.0) | 531,457 | (81.1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| America | 444 | (10.7) | 76,437 | (11.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Asia | 301 | (7.3) | 47,611 | (7.3) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Although all of the studies used a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), the number of food items assessed varied widely (Table 3). Two studies [22, 24] only asked three and two specific items (beer, coffee and decaffeinated coffee), while others assessed dietary intake in more detail (from 9 [27] to 788 food items [12]). The mean number of food items per questionnaire was 107 and 132 after exclusion of those studies that reported only on beverages [14, 22, 24]. Most studies with a FFQ of more than 40 items had detailed information on dietary intake of meat, vegetables, fruit and beverages. The use of a validated FFQ questionnaire was reported in eight studies [12, 19, 23, 28–30, 32–34], while one study checked the reproducibility of its FFQ [20]. Most of the studies assessed portion size, while four studies [12, 28, 29, 33, 34] reported the quantitative intake of food items in grams. Six studies [10, 19, 28, 30, 32–34] also provided data on nutrients.

Table 3.

Number of food items and portion size reported by each study within the Bladder cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants study (BLEND)

| Study | Food items (n) | Portion size |

|---|---|---|

| Case–control studies | ||

| Los-Angeles bladder cancer Case–control study [10] | 49 | Yes |

| Roswell Park Cancer Institute [11] | 44 | Yes |

| Belgian Case–control study on bladder cancer [12] | 788 | Yes |

| Aichi Prefecture Case–control study [13] | 107 | Yes |

| Kaohsiung [14] | 41 | Yes |

| Hessen Case–control study on bladder cancer [15] | 26 | No |

| Stockholm Case–control study [16] | 188 | Yes |

| Roswell Park Memorial Institute Case–control study on bladder cancer [17] | 64 | Yes |

| Reina Sofia University [18] | 17 | No |

| New Hampshire bladder cancer study [19] | 121 | Yes |

| Italian Case–control study on bladder cancer [20] | 21 | No |

| Brescia bladder cancer study [21] | 40 | Yes |

| Dortmund Hörde study [22] | 3 | Yes |

| National Enhanced Cancer Surveillance System (NESCC) [23] | 69 | Yes |

| French INSERM study [24] | 2 | No |

| South and East China Case–control study on bladder and prostate cancer [25] | 52 | No |

| Molecular Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer and Prostate Cancer [26] | 90 | Yes |

| North Carolina case control study [27] | 9 | No |

| Cohort studies | ||

| Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC) & the Cohort of Swedish Men [28] | 96 | No |

| Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer, the Netherlands, 1986–2003 [29] | 150 | Yes |

| Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study [30] | 98 | Yes |

| RERF atomic bomb survivors Study [31] | 102 | No |

| Vital study [32] | 126 | Yes |

| European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) [33, 34] | 260a | Yes |

aDietary intake was assessed by a number of different instruments in the participating countries and the number of different food items varied from 88 (Norway) to 2443 (Sweden)

The consumption of beverages was reported in all the eighteen case–control studies. Five case–control studies [12, 13, 16, 19, 26] had detailed information for each of the larger food categories of the Eurocode 2 Food Coding System, while three studies [11, 23, 25] missed only data on sugar and/or fat (Table 4). Fat, grains, nuts and sugar were also missing in another four studies [10, 15, 17, 20]. The six cohort studies [28–34] had detailed information in each food categories with the exception of the RERF atomic bomb survivors study [31] which had no data on sugar intake.

Table 4.

Numbers of cases and controls available for each food category included in the Bladder cancer Epidemiology and Nutritional Determinants study (BLEND)

| All Countries | Europe | America | Asia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| Food category (number of studies) | Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

Ca N |

Co N |

| Case–control studies | ||||||||||||||||

| Milk and milk products (13) [10–17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 26] | 4,734 | 9,251 | 1,388 | 7,442 | 1,231 | 1,514 | 266 | 783 | 2,838 | 7,005 | 962 | 6,464 | 665 | 732 | 160 | 195 |

| Eggs and eggs products (11) [10–13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 23, 25, 26] | 4,299 | 6,531 | 1,255 | 3,974 | 1,230 | 1,512 | 265 | 781 | 2,436 | 4,141 | 839 | 3,034 | 633 | 605 | 151 | 159 |

| Meat and meat products (12) [10–13, 15–17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 26] | 4,699 | 9235 | 1,377 | 7,716 | 1,231 | 1,513 | 265 | 783 | 2,833 | 7,114 | 961 | 6,774 | 635 | 608 | 151 | 159 |

| Fish and fish products (11) [11–13, 15–17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 26] | 3,197 | 7,391 | 960 | 7,144 | 1,229 | 1,511 | 265 | 781 | 1,335 | 5,275 | 544 | 6,204 | 633 | 605 | 151 | 159 |

| Fats and oils (7) [10–13, 16, 19, 26] | 2,299 | 2,292 | 634 | 984 | 371 | 500 | 94 | 419 | 1,689 | 1,559 | 484 | 506 | 239 | 233 | 56 | 59 |

| Grain and grain products (11) [10–13, 16, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 26] | 4,050 | 8,481 | 1,209 | 7,404 | 574 | 721 | 94 | 424 | 2,841 | 7,153 | 964 | 6,821 | 635 | 607 | 151 | 159 |

| Pulses, seeds and nut products (8) [11–13, 16, 19, 23, 25, 26] | 2,108 | 4,255 | 715 | 3,270 | 371 | 499 | 94 | 421 | 1,106 | 3,151 | 470 | 2,690 | 631 | 605 | 151 | 159 |

| Vegetables (13) [10–13, 15–17, 19–21, 23, 25, 26] | 4,942 | 10,086 | 1,403 | 8,648 | 1,429 | 1,727 | 265 | 783 | 2,881 | 7,754 | 987 | 7,706 | 632 | 605 | 151 | 159 |

| Fruit and fruit products (13) [10–13, 15–17, 19–21, 23, 25, 26] | 4,860 | 9,307 | 1,376 | 7,615 | 1,414 | 1,713 | 265 | 781 | 2,814 | 6,989 | 960 | 6,675 | 632 | 605 | 151 | 159 |

| Sugar products (7) [12, 13, 16, 18, 19, 23, 26] | 1,613 | 3,438 | 582 | 3,020 | 446 | 591 | 105 | 463 | 935 | 2,615 | 421 | 2,499 | 232 | 232 | 56 | 58 |

| Beverages (18) [10–27] | 5,509 | 10193 | 1,538 | 7,640 | 1,814 | 2,269 | 357 | 926 | 3,030 | 7,192 | 1,021 | 6,519 | 665 | 732 | 160 | 195 |

| Cohort studies | ||||||||||||||||

| Milk and milk products (6) [28–34] | 2,615 | 184,424 | 1,159 | 422,716 | 2,495 | 146,183 | 835 | 384,864 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2,488 | 10 | 4,110 |

| Eggs and eggs products (6) [28–34] | 2,585 | 184,284 | 1,147 | 421,392 | 2,465 | 146,039 | 823 | 383,535 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2,492 | 10 | 4,115 |

| Meat and meat products (6) [28–34] | 2,614 | 184,420 | 1,156 | 422,122 | 2,494 | 146,171 | 832 | 384,262 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2,496 | 10 | 4,118 |

| Fish and fish products (6) [28–34] | 2,613 | 184,406 | 1,157 | 421,976 | 2,493 | 146,157 | 833 | 384,116 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2,496 | 10 | 4,118 |

| Fats and oils (6) [28–34] | 2,527 | 181,544 | 1,130 | 421,335 | 2,420 | 146,029 | 810 | 384,710 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 21 | 1,762 | 6 | 2,883 |

| Grain and grain products (6) [28–34] | 2,618 | 184,446 | 1,158 | 422,738 | 2,498 | 146,194 | 834 | 384,876 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 24,99 | 10 | 4,120 |

| Pulses, seeds and nut products (6) [28–34] | 2,563 | 184,228 | 1,143 | 420,368 | 2,443 | 145,984 | 819 | 382,512 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2,491 | 10 | 4,114 |

| Vegetables (6) [28–34] | 2,616 | 184,432 | 1,157 | 422,236 | 2,496 | 146,184 | 833 | 384,376 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2495 | 10 | 4118 |

| Fruit and fruit products (6) [28–34] | 2,607 | 184,416 | 1,155 | 421,526 | 2,487 | 146,170 | 831 | 383,666 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 34 | 2493 | 10 | 4118 |

| Sugar products (5) [28–30, 32–34] | 2,556 | 181,860 | 1,143 | 417,615 | 2,470 | 146,107 | 829 | 383,873 | 86 | 35,753 | 314 | 33,742 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Beverages (6) [28–34] | 2,630 | 187,445 | 1,172 | 424,778 | 2,497 | 146,190 | 835 | 384,868 | 99 | 38,760 | 327 | 35,793 | 34 | 2495 | 10 | 4117 |

Abbreviations: Ca cases, Co controls, N number

Discussion

The high number of cases (11,261) and controls (675,532) from 24 epidemiological studies included in the BLEND study makes the BLEND study the largest dataset on diet and UBC worldwide. A large sample size provides the potential to analyze in more detail food items rarely consumed [35] and allows delineating the generally weak association between UBC cancer and dietary intake for food categories. The advantage of pooling individual data compared to meta-analysis of aggregate data are multiple: it increases the power to detect the effect for food items more rarely consumed, it allows to adjust for the same confounding factors, gender, age, and smoking status, to test for interaction and to perform subgroup analyses [36, 37].

Demographic data in the BLEND study are consistent with the IARC CancerBase [1]. The male/female ratio in our dataset was 3:1. Worldwide the male/female ratio is 3.3:1. Europe is responsible for nearly 40 % of the UBC cases worldwide while the Asian population account for 28 % of the UBC incidence [1]. In our dataset, 49 % of the cases are from Europe while only 10 % of the cases are from Asia. The African and the Eastern Mediterranean region is responsible for only 9 % of the UBC incidence worldwide [1]. These regions are not represented in our dataset. In America and Europe, more than 90 % of the UBC cases are transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), while in Africa, up tot 40 % of the UBC cases can be squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) [38, 39] due to infection with Schistosoma haematobium (Bilharziasis) [40]. The Egyptian multi-center case–control study [41] had not yet been published when we collected our data. So, pooling of the data of the different countries is possible because most industrialized countries are likely to share the same risk factors for UBC. Otherwise, it will be possible to stratify analyses by region given the large number of included participants. We aim to update the BLEND database in the future with new available studies.

Conclusion

The available data in the very large BLEND database will allow us to test associations between individual food items of the different food items categories, even those less commonly consumed, and the risk for UBC. We will also investigate food patterns such as the Mediterranean diet and the influence of nutrients on the risk of UBC. In addition, the large sample size will allow subgroup analyses.

Abbreviations

BLEND, the BLadder cancer, Epidemiology, and Nutritional Determinants study; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; OR, odds ratio; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SD, standard deviation; TCC, transitional cell carcinoma; TNM, TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors; UBC, urinary bladder cancer; WCRF, World Cancer Research Fund.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all principal investigators for their willingness to participate in this jointed project.

Funding

Hessen Case–control study on bladder cancer was supported by the Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz (No. F 1287). The Aichi Prefecture Case–control study was supported by a Smoking Research Foundation Grant for Biomedical Research. The Kaohsiung study was supported by grant NSC 85-2332-B-037-066 from the National Scientific Council of the Republic of China. The Stockholm Case–control study was supported by grant from the Swedish National Cancer Society and from the Swedish Work Environment Fund. The Roswell Park Memorial Institute Case–control study on bladder cancer was supported by Public Health Service Grants CA11535 and CA16056 from the National Cancer Institute.

The New England bladder cancer study was funded in part by grant numbers 5 P42 ES007373 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH and CA57494 from the National Cancer Institute, NIH. The Italian Case–control study on bladder cancer was conducted within the framework of the CNR (Italian National Research Council) Applied Project “Clinical Application of Oncological Research” (contracts 94.01321.PF39 and 94.01119.PF39), and with the contributions of the Italian Association for Cancer Research, the Italian League against Tumours, Milan, and Mrs. Angela Marchegiano Borgomainerio.

The Brescia bladder cancer study was partly supported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The French INSERM study was supported by a grant from the Direction Générale de la Santé, Ministère des Affaires Sociales, France. The Molecular Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer and Prostate Cancer was supported in part by grants ES06718 (to Z.-F.Z.), U01 CA96116 (to A.B.), and CA09142 from the NIH National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Cancer Institute, the Department of Health and Human Services, and by the Ann Fitzpatrick Alper Program in Environmental Genomics at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, UCLA. The Swedish Mammography Cohort (SMC) & the Cohort of Swedish Men was supported by the Swedish Cancer Foundation, Örebro County Council Research Committee, and Swedish Research Council Committee for Infrastructure. The Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society. The RERF atomic bomb survivors Study was supported by The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, a public interest foundation funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and the US Department of Energy (DOE). The research was also funded in part through DOE award DE-HS0000031 to the National Academy of Sciences. This publication was supported by RERF Research Protocol RP-A5-12. The VITamins and Lifestyle Study (VITAL) was supported by a grant (R01CA74846) from the National Cancer Institute. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) was carried out with financial support of the ‘Europe Against Cancer’ Programme of the European Commision (SANCO); Ligue contre le Cancer (France); Société 3 M (France); Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale; Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM); Institute Gustave Roussy; German Cancer Aid; German Cancer Research Centre; German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Danish Cancer Society; Health Research Fund (FIS) of the Spanish Ministry of Health; the Spanish Regional Governments of Andalucia, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra; Cancer Research UK; Medical Research Council, UK; Stroke Association, UK; British Heart Foundation; Department of Health, UK; Food Standards Agency, UK; Wellcome Trust, UK; Greek Ministry of Health; Greek Ministry of Education; Italian Association for Research on Cancer; Italian National Research Council; Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports; Dutch Prevention Funds; LK Research Funds; Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland); World Cancer Research Fund; Swedish Cancer Society; Swedish Scientific Council; Regional Government of Skane, Sweden; Norwegian Cancer Society; Norwegian Research Council. Partial support for the publication of this supplement was provided by the Centre de Recherche et d’Information Nutritionnelles (CERIN).

Availability of data and material

The dataset described in this article will be available at Dataverse (https://dataverse.nl/dvn/).

Authors’ contributions

MEG collected and harmonized data, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. F.I., D.M., R.R. and A.W. harmonized the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.B. collected the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. SB, BB, MFA, KG, EG, XJ, KCJ, MRK, EK, ClV, CML, JM, HP, SP, GS, LT, JT, PvdB, PJV, KW, EW, EW, AW and ZFZ provided the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. FB reviewed and edited the manuscript, and MPZ. supervised the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

This study was partly funded by the World Cancer Research Fund.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each participating study has been approved by the local ethic committee.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2013;Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx (Accessed 18 Feb 2014).

- 2.Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Hauser RS, Laskin BL, Redaelli A. Quality of life aspects of bladder cancer: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(6):675–688. doi: 10.1023/A:1025144617752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooksley CD, Avritscher EB, Grossman HB, Sabichi AL, Dinney CP, Pettaway C, et al. Clinical model of cost of bladder cancer in the elderly. Urology. 2008;71(3):519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Cancer research Fund/ American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC: AIRC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Report: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Bladder Cancer. Available at: http://wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Bladder-Cancer-2015-Report.pdf. 2015 (Accessed 11 Feb 2016).

- 6.Reulen RC, Kellen E, Buntinx F, Zeegers MP. Bladder cancer and occupation: a report from the Belgian case–control study on bladder cancer risk. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50(6):449–454. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unwin I. Eurocode 2 Core classification version 99/1. http://www.ianunwin.demon.co.uk/eurocode/docmn/ec99/ecmg01cl.htm. 1999 (Accessed Sept 2010).

- 8.Poortvliet EJ, Klensin JC, Kohlmeier L. Rationale document for the eurocode food coding system. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992;46(Suppl5):S9–S24. [PubMed]

- 9.NIST/SEMATECH. e-Handbook of Statistical Methods, Scatterplot:Outlier, http://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/scattera.htm. 2013:1.3..26.10. (Accessed 29 Sept 2015).

- 10.Jiang X, Castelao JE, Groshen S, Cortessis VK, Ross RK, Conti DV, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of bladder cancer in Los Angeles county. Int j cancer J int du cancer. 2007;121(4):839–845. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang L, Zirpoli GR, Guru K, Moysich KB, Zhang Y, Ambrosone CB, et al. Consumption of raw cruciferous vegetables is inversely associated with bladder cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev: pub Am Assoc Cancer Res, cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2008;17(4):938–944. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellen E, Zeegers M, Paulussen A, Van Dongen M, Buntinx F. Fruit consumption reduces the effect of smoking on bladder cancer risk. The Belgian case control study on bladder cancer. Int j cancer J int du cancer. 2006;118(10):2572–2578. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakai K, Takashi M, Okamura K, Yuba H, Suzuki K, Murase T, et al. Foods and nutrients in relation to bladder cancer risk: a case–control study in Aichi prefecture. Central Japan Nutr Cancer. 2000;38(1):13–22. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC381_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu CM, Lan SJ, Lee YH, Huang JK, Huang CH, Hsieh CC. Tea consumption: fluid intake and bladder cancer risk in southern Taiwan. Urology. 1999;54(5):823–828. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pohlabeln H, Jöckel KH, Bolm-Audorff U. Non-occupational risk factors for cancer of the lower urinary tract in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15(5):411–419. doi: 10.1023/A:1007595809278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steineck G, Hagman U, Gerhardsson M, Norell SE. Vitamin a, supplements, fried foods, fat and urothelial cancer. A case-referent study in Stockholm in 1985–87. Int j cancer J int du cancer. 1990;45(6):1006–1011. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mettlin C, Graham S. Dietary risk factors in human bladder cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(3):255–263. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baena AV, Allam MF, Del Castillo AS, Diaz-Molina C, Requena Tapia MJ, Abdel-Rahman AG, et al. Urinary bladder cancer risk factors in men: a Spanish case–control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2006;15(6):498–503. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000215618.05757.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brinkman MT, Karagas MR, Zens MS, Schned A, Reulen RC, Zeegers MP. Minerals and vitamins and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the New Hampshire study. Cancer causes control : CCC. 2010;21(4):609–619. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Decarli A, Benichou J. Attributable risks for bladder cancer in northern Italy. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5(6):427–431. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen M, Hung RJ, Brennan P, Malaveille C, Donato F, Placidi D, et al. Polymorphisms of the DNA repair genes XRCC1, XRCC3, XPD, interaction with environmental exposures, and bladder cancer risk in a case–control study in northern Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev : pub Am Assoc Cancer Res, cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2003;12(11 Pt 1):1234–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ovsiannikov D, Selinski S, Lehmann ML, Blaszkewicz M, Moormann O, Haenel MW, et al. Polymorphic enzymes, urinary bladder cancer risk, and structural change in the local industry. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75(8–10):557–565. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2012.675308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson KC, Mao Y, Argo J, Dubois S, Semenciw R, Lava J. The national enhanced cancer surveillance system: a case–control approach to environment-related cancer surveillance in Canada. Envirometrics. 1998;9:495–504. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-095X(199809/10)9:5<495::AID-ENV318>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clavel J, Cordier S. Coffee consumption and bladder cancer risk. Int j cancer J int du cancer. 1991;47(2):207–212. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemelt M, Hu Z, Zhong Z, Xie LP, Wong YC, Tam PC, et al. Fluid intake and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the south and east china case–control study on bladder cancer. Int j cancer J int du cancer. 2010;127(3):638–645. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao W, Cai L, Rao JY, Pantuck A, Lu ML, Dalbagni G, et al. Tobacco smoking, GSTP1 polymorphism, and bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2400–2408. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor JA, Umbach DM, Stephens E, Castranio T, Paulson D, Robertson C, et al. The role of N-acetylation polymorphisms in smoking-associated bladder cancer: evidence of a gene-gene-exposure three-way interaction. Cancer Res. 1998;58(16):3603–3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson SC, Andersson SO, Johansson JE, Wolk A. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of bladder cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev : pub Am Assoc Cancer Res, cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2008;17(9):2519–2522. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeegers MP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Are retinol, vitamin C, vitamin E, folate and carotenoids intake associated with bladder cancer risk? results from the Netherlands cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(7):977–983. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behrens G, Leitzmann MF, Sandin S, Lof M, Heid IM, Adami HO, et al. The association between alcohol consumption and mortality: the Swedish women's lifestyle and health study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(2):81–90. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9545-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozasa K, Shimizu Y, Suyama A, Kasagi F, Soda M, Grant EJ, et al. Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors, report 14, 1950–2003: an overview of cancer and noncancer diseases. Radiat Res. 2012;177(3):229–243. doi: 10.1667/RR2629.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White E, Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Thornquist M, King I, Shattuck AL, et al. VITamins and lifestyle cohort study: study design and characteristics of supplement users. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(1):83–93. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riboli E, Kaaks R. The EPIC project: rationale and study design. European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(Suppl 1):S6–S14. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, Ferrari P, Norat T, Fahey M, et al. European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6B):1113–1124. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souverein OW, Dekkers AL, Geelen A, Haubrock J, de Vries JH, Ocke MC, et al. Comparing four methods to estimate usual intake distributions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(Suppl 1):S92–S101. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blettner M, Sauerbrei W, Schlehofer B, Scheuchenpflug T, Friedenreich C. Traditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(1):1–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goossens ME, Buntinx F, Zeegers MP. Aetiology, demographics and risk factors for bladder cancer. In: The Oxford textbook of surgery. Oxford University Press (OUP). 2016, in press.

- 39.Parkin DM. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2008;218:12–20. doi: 10.1080/03008880802285032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sitas F, Parkin DM, Chirenje M, Stein L, Abratt R, Wabinga H. Part II: cancer in indigenous Africans--causes and control. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):786–795. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng YL, Amr S, Saleh DA, Dash C, Ezzat S, Mikhail NN, et al. Urinary bladder cancer risk factors in Egypt: a multicenter case–control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev : pub Am Assoc Cancer Res, cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2012;21(3):537–546. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]