Abstract

Background

Antibacterial coatings of medical devices have been introduced as a promising approach to reduce the risk of infection. In this context, diamond-like carbon coated polyethylene (DLC-PE) can be enriched with bactericidal ions and gain antimicrobial potency. So far, influence of different deposition methods and ions on antimicrobial effects of DLC-PE is unclear.

Methods

We quantitatively determined the antimicrobial potency of different PE surfaces treated with direct ion implantation (II) or plasma immersion ion implantation (PIII) and doped with silver (Ag-DLC-PE) or copper (Cu-DLC-PE). Bacterial adhesion and planktonic growth of various strains of S. epidermidis were evaluated by quantification of bacterial growth as well as semiquantitatively by determining the grade of biofilm formation by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Additionally silver release kinetics of PIII-samples were detected.

Results

(1) A significant (p < 0.05) antimicrobial effect on PE-surface could be found for Ag- and Cu-DLC-PE compared to untreated PE. (2) The antimicrobial effect of Cu was significantly lower compared to Ag (reduction of bacterial growth by 0.8 (Ag) and 0.3 (Cu) logarithmic (log)-levels). (3) PIII as a deposition method was more effective in providing antibacterial potency to PE-surfaces than II alone (reduction of bacterial growth by 2.2 (surface) and 1.1 (surrounding medium) log-levels of PIII compared to 1.2 (surface) and 0.6 (medium) log-levels of II). (4) Biofilm formation was more decreased on PIII-surfaces compared to II-surfaces. (5) A silver-concentration-dependent release was observed on PIII-samples.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study suggest that PIII as a deposition method and Ag-DLC-PE as a surface have high bactericidal effects.

Keywords: Implant-associated infections, Diamond-like carbon, Silver, Copper, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Antibacterial coating

Background

Implant-associated bacterial infections are one of the most serious complications in orthopedic surgery, representing a significant healthcare and economic burden [1]. Management of these infections often requires multiple debridement surgeries, and long-term systemic antibiotic therapy, despite the associated side effects and additional complications [2]. One of the major problems in septic surgery is the formation of biofilm on implanted foreign materials [3, 4]. These extracellular polysaccharide layers impede the activity of the host defenses and antibiotic therapy, leading to a 1000-fold decreased susceptibility to antimicrobial agents, and further promotion of bacterial survival and growth [5]. Once a significant amount of biofilm has formed, eradication of infection is nearly impossible without removing the implant. Therefore, prevention of these infections has an important impact on patient’s morbidity and the cost effectiveness of hospital care [6]. In this context, employment of implant materials or coatings that control infection and biofilm formation are particularly advantageous [7]. This led to the development of antiadhesive and antibacterial surfaces. The first mentioned coatings (e.g. polyethylene glycol, polyethylene oxide brushes) reduce bacterial adhesion by altering the physicochemical properties of the substrate. Thus, formation of protein surface layers (conditioning films) on the implant and bacteria-substrate interactions are hindered [8]. However, the effectiveness of these coatings for reducing bacterial adhesion is very limited and varies markedly depending on bacterial species. On the other hand, non-antibiotic antibacterial coatings actively release bactericidal agents, e.g. silver (Ag)- [9, 10] and/or copper (Cu) [11]. In contrast to antibiotics these ions act more broadly against a wide range of bacteria, and microbes that are not intrinsically resistant [12] will rarely develop resistance [13]. However, there are concerns regarding a possible toxicity of silver-coated medical devices [10]. Cu on the other hand has been shown to possess outstanding antibacterial but nevertheless bio-tolerant features [11, 14]. A problem concerning Ag and Cu as bactericidal agents in coatings is the fact that they can hardly be embedded on wear surfaces, e.g. polyethylene (PE). PE is in widespread use in total joint arthroplasty due to its outstanding mechanical properties as a wear surface and simultaneously its high biocompatibility. On the other hand PE is highly prone to bacterial adherence. In total knee replacement roughly half of the surface is exposed to synovial fluid and in main parts tribologically active. Therefore in septic knee surgery major portions of the susceptible prosthesis are not protected against bacterial reinfection. A potential solution to this problem could be the use of antibacterial-agent-enriched diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings. DLC coatings can act as local antibacterial agents if release of Ag (Ag+)- or Cu (Cu++)-ions is provided [15–17], and at the same time exhibit excellent tribological features if used for hip or knee arthroplasty [18–21]. In spite of these promising results, to our best knowledge, comprehensive studies on antibacterial effects of DLC coatings on soft wear surfaces, e.g. polyethylene (PE), comparing Ag and Cu have not been conducted so far. Additionally, data on the use of different deposition methods for DLC coatings and its influence on antimicrobial effects are still lacking.

In this report the antimicrobial effects of Ag- and Cu-incorporated DLC coatings on PE manufactured with different techniques are described. The coatings and films were deposited by two methods of IBAD (plasma immersion ion implantation (PIII) and conventional ion implantation (II)). Bactericidal potency of DLC specimens enriched with Ag or Cu was studied on the surface and the surrounding fluid medium. This study provides valuable information for determining the suitability of DLC-PE enriched with Ag or Cu. Ethics approval for this study was not necessary according to the institutional review board (TU München).

Methods

DLC film deposition

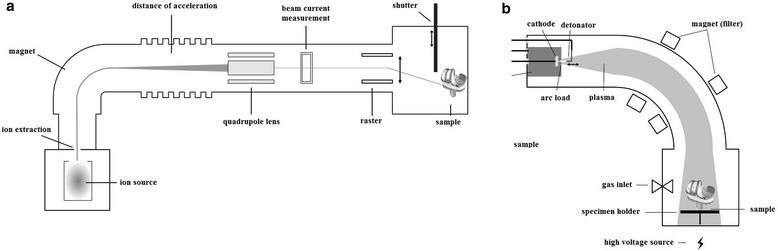

To incorporate Ag or Cu homogenously within the DLC matrix of PE-samples modified techniques of ion irradiation of polymers were applied: DLC-processing was achieved by either conventional, direct ion implantation (II) via ion bombardment or plasma immersion ion implantation (PIII) [22]. Both methods are described schematically in Fig. 1. Main disadvantage of conventional II is that only a relatively small part of the surface which is targeted by the beam can be enriched with ions. This makes ion-containing DLC-processing of 3D-surfaces (e.g. joint prostheses) time-consuming and expensive. On the other hand, ion implantation with PIII is easy to perform due to the liquid plasma state of the coating fluid. This allows coating of complex shaped surfaces without major efforts. In contrast to common DLC techniques (e.g., physical vapor deposition) with both methods used in this study the PE-surface is not coated with DLC but rather modified by ion implantation. Due to the kinetic energy of the implanted ions, the polymer surface is modified from crystalline PE to amorphous DLC, while the metal ions agglomerate to nano-particles directly under the surface. In this way, the implantation of ions leads to a wear-resistant, antibacterial PE surface reducing the risk of detachment compared to surface coatings [23].

Fig. 1.

Scheme of deposition methods for ions: a) direct ion implantation (II), b) plasma immersion ion implantation (PIII); Note: II allows incorporation of ions only on the sample surface struck by the ion beam; PIII allows homogenous incorporation of ions on complex shaped surfaces due to liquid plasma state of the ion beam

Sample features

Study objects were cylindrical substrates (diameter: 10 mm, height: 2 mm; Goodfellow GmbH, Nauheim, Germany) of ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene (PE). The samples were investigated in different groups with modified parameters of implantation: Firstly, to determine which of the ions (Ag or Cu) exhibits higher bactericidal potency (first group) and secondly, to determine the influence of different deposition methods (second group). All sample features and testing groups are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of DLC conversion and antibacterial effect of different surfaces compared to untreated PE

| DLC-processing (implantation energy, fluence) | Surface adhesion [CFU; mean +/− SD] | Bacterial growth of Ag-DLC-PE [log-levels a/ %]b | p-values | Planktonic growth [CFU/ml; mean +/− SD] | Bacterial growth of Ag-DLC-PE [log-levelsa / %]b | p-values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison of antibacterial ions deposited with II: Ag vs. Cu | II (Ag): 60 keV, 1x1017 cm−2 | 2.6x103+/− 2.5x103 | −0.8 / - 85.6 % | <.05* | 1.7x105+/− 8.5x104 | +0.05 / +13.3 % | >.05* | 1st Group |

| II (Cu): 55 keV, 1x1017 cm−2 | 9.0x103+/− 2.6x103 | −0.3 / -50.0 % | <.05* | 1,6x105+/− 9.5x104 | +0.03 /+6.6 % | >.05* | 1st Group | |

| II (Ag) vs. II (Cu) | <.05 | >.05 | 1st Group | |||||

| Untreated PE | 1.8x104+/− 9.4x103 | 1.5x105+/− 2.8x104 | 1st Group | |||||

| Comparison of deposition methods: PIII vs. II | PIII (Ag): 5 kV, 1x1017 cm−2 | 2,5x102 +/− 1.5x102 | −2.2 / -99.1 % | <.05* | 1,1x104+/− 2.5x103 | −1.1 / - 96.3 % | <.05* | 2nd Group |

| II (Ag): 10 keV, 1x1017 cm−2 | 2,3x103+/− 3.5x102 | −1.2 / -92.0 % | <.05* | 3,6x104+/− 1.2x103 | −0.6 / - 88.0 % | <.05* | 2nd Group | |

| PIII (Ag) vs. II (Ag) | <.05 | <.05 | 2nd Group | |||||

| Untreated PE | 2.9x104 +/− 2.0x104 | 3.0x105+/− 6.5x104 | 2nd Group |

alog-levels = bacterial counts calculated as shown in following equation: log-levels = log10(CFU of Ag-DLC-PE) – log10(CFU of untreated PE)

bpositive values (log-levels/%) express increased bacterial growth on Ag-DLC-PE compared to PE, negative values express reduced bacterial growth on Ag-DLC-PE compared to PE fluence = amount of ions received by a surface per unit area [ions/cm2]

* = compared to untreated PE

PIII (Ag) plasma immersion ion implantation of Ag-ions

II (Ag/Cu) conventional ion-implantation with Ag- or Cu-ions

CFU colony forming units

SD standard deviation

In the first group Ag-doped (fluence: 1x1017 cm−2, ion energy: 60 keV) and Cu-doped samples (fluence: 1x1017 cm−2; ion energy: 55 keV) were assembled for direct comparison of antibacterial activity of these ions. DLC processing was carried out via II of Ag- or Cu-ions. Ion energy was chosen according to previous results, where these enrgies led to a superficial implantation of ions allowing dissolution onto the surface and therefore exhibiting bactericidal effects. With this features the effect of fluence and implantation depth can be minimized so that the intrinsic bactericidal effects of the ions can be estimated. Ion energy of Cu-samples was lower compared to Ag-samples due to the fact that Cu-ions penetrate easier into the PE-surface. Therefore Cu-ions reach the same penetration depth as Ag-ions with lower implantation energies. Based on the findings of the first group the second group was assembled with two different methods of ion deposition: PIII (fluence: 1x1017 cm−2; pulse voltage: 5 kV) vs. II (fluence: 1x1017 cm−2; ion energy: 10 keV). Again, different ion energies were applied for either methods to allow equal penetration depth of ions into the samples. Non-modified PE samples served as a control.

After sample preparation incubation for 24 h with Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC35984) was carried out. Thereafter, antimicrobial effects on the sample’s surface (i.e. bacterial sessile growth) and the surrounding fluid medium (i.e. bacterial planktonic growth) were investigated.

Evaluation of silver release

Silver release kinetics was evaluated for samples with the highest intrinsic antimicrobial potency, namely Ag-DLC-PE samples deposited with PIII. Sample plates were placed into 10 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and kept sealed for 10 days at 37 °C. Every 24 h PBS was harvested and replaced. For every Ag-enriched sample type (fluences: 1 × 1017, 5 × 1016 and 1 × 1016 cm−2) five specimens were investigated. Untreated PE served as control. Analysis of silver release kinetics of the harvested PBS was conducted via ICP-OES (inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy, Fa. Varian, Vista-MPX, Kleve, Germany).

Sterilization of samples and sealing of surfaces with paraffin wax

Samples were treated according to a previously described standardized method [24]. Briefly summarized, specimens were rinsed with distilled water for 10 min, air-dried in a laminar flow cabinet and thereafter sterilized with gamma-beam with the dose of 26.5 kGy (Isotron Deutschland GmbH, Allershausen, Germany).

Bacterial sample preparation

The bacterial strains used in the present study were S. epidermidis (ATCC 35984; LGC Standards GmbH, Wesel, Germany) for determination of surface and planktonic growth and a strong biofilm-forming variant of S. epidermidis (RP62a; LGC Standards GmbH, Wesel, Germany) for scanning electron microscopy (SEM-) evaluation of biofilm formation on the samples. These strains are of major clinical importance in implant-associated infections [25, 26]. Test strains were routinely cultured in Columbia Agar with 5 % sheep blood (S. epidermidis, ATCC 35984) or Trypticase™ Soy Agar (S. epidermidis, RP62a) (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) at 37 °C overnight before testing. Bacteria were then harvested by centrifugation, rinsed, suspended, diluted in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and adjusted by densitometry to a MacFarland 0.5 standard (MacFarland Densimat™, BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). To control bacterial concentration, 100 μl of each suspension was again cultured for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h serial dilutions of this suspension were plated on Colombia-Agar. The colonies were counted and colony numbers calculated accordingly. For the study every suspension with its known bacterial concentration was diluted with DMEM + 10 % FCS to reach the targeted value for bacterial concentration (105 CFU/ml). Sample plates with paraffin-coated lower surfaces were placed in 24-well culture plates and 1 ml of 105 CFU/ml bacterial suspensions were added. Incubation of the well plates was conducted for 24 h at 37 °C.

Microbiological analysis

Bacterial surface adhesion was evaluated by determining bacterial concentration on the specimen. Bacterial planktonic growth was measured in the growth medium. For every group four independent testing runs with four different samples were conducted. Therefore, altogether 16 samples were tested for every group.

Determination of bacterial growth on the sample surface

Colonized sample plates were removed from the wells with a sterile forceps, carefully rinsed twice with sterile PBS, transferred to vials containing 3 ml of sterile PBS and sonicated for 7 min (Elmasonic S60H, Elma, Singen, Germany) to remove adhering bacteria. 100 μl of the fluid were aspirated, plated on Colombia Agar at 37 °C for 24 h and quantified after incubation (CFU/ml, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of bacterial growth (CFU: colony-forming units)

SEM-analysis was conducted semiquantitatively to evaluate inhibition of biofilm formation. SEM-images were compiled of native DLC coated PE samples and Ag-DLC-PE samples treated with II and PIII. Biofilm formation was quantified in five categories: (1) no biofilm formation, (2) biofilm covering less than 25 % of the surface, (3) biofilm covering between 25 and 75 % of the surface, (4) biofilm covering more than 75 % of the surface, (5) biofilm formation covering the entire surface. Two different observers (NH, SJ) graded five randomly chosen fields of every sample in three runs.

Determination of bacterial planktonic growth

A 700-μl volume of each well was supplemented with 700 μl neutralizing solution as described by Tilton: 1,0 g sodium thioglycolate + 1,46 g sodium thiosulfate in 1.000 ml deionized water [27]. The neutralizing solution acts as an inhibitor for reminiscent metal toxicity on bacteria. The suspension was plated on Columbia Agar after serial dilutions and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Thereafter, CFU were quantified and extrapolated to CFU/ml (Fig. 2).

Statistics

All results are presented as means ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was computed using non-parametric methods and the method of closed testing procedure (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann–Whitney U test). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were performed with use of SPSS (version 20.0; Chicago, Illinois). Statistical analysis was conducted per consultation with the Institute of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology (Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany).

Results

Antimicrobial effect of Cu- and Ag-DLC-PE with equal penetration depth of ions in the surface layers (ion energy: 55 keV for Cu and 60 keV for Ag) and equal fluences (1x1017 cm−2)

Compared to untreated PE on Cu- and Ag-DLC-PE samples a significantly decreased bacterial growth was evident (Table 1, Fig. 3). Comparison of Cu- and Ag-DLC-PE samples among each other revealed a significant reduction of bacterial surface growth on Ag-DLC-PE samples. Analysis of planktonic growth in the supernatant growth medium showed no significant antibacterial effects neither for Cu- nor Ag-DLC-PE samples (Table 1, Fig. 3). Due to superior bactericidal effects of Ag-DLC-PE compared to Cu-DLC-PE further testing was only conducted with Ag-specimens.

Fig. 3.

Bacterial growth of S. epidermidis in the Cu- and Ag-DLC-PE testing group 1 with comparison of bactericidal potency of Ag- and Cu-ions (t = 0: before incubation; t = 24 h: after incubation); * = p < .05 (compared to untreated PE)

Antimicrobial effect of Ag-DLC–PE processed with different deposition techniques (PIII vs. II) and equal fluences (1x1017 cm−2)

Samples treated with PIII and II showed both a significantly decreased bacterial surface adhesion compared to PE by 2.2 and 1.2 log-levels respectively. Comparison of PIII and II revealed a significant reduced amount of bacteria for PIII-samples. Analysis of planktonic growth showed again significantly reduced bacterial concentrations for either deposition techniques. Similar differences were found for bacterial concentrations in the surrounding medium (Table 1, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Bacterial growth of S. epidermidis in the Ag-DLC-PE testing group 2 with comparison of different deposition methods (t = 0: before incubation; t = 24 h: after incubation; PIII: plasma immersion ion implantation; II: direct ion implantation); * = p < .05 (compared to untreated PE)

Surface biofilm formation in scanning electron micrographs

Biofilm formation was ubiquitous and graded type 5 on all native PE samples. The entire specimen surfaces were covered with thick layers of S. epidermidis. Ag-DLC-PE samples treated with II on the other hand showed biofilm inhibiting effects with at the most rare spot-like biofilm formation. Average grading for this group were type 4. Samples treated with PIII showed less biofilm formation compared to II-samples. Average grading for this group were type 3 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

SEM-images to exemplify biofilm formation on different polyethylene surfaces. Homogenous biofilm grade 5 after incubation with S. epidermidis on native PE (a), reduced biofilm grade 3 on Ag-DLC-PE processed with PIII (5 kV, 1x1017 cm−2, b)

Silver release kinetics

Silver release kinetics was evaluated for samples which provided the highest bactericidal potency (PIII-samples). Ag concentration of untreated PE throughout the 10 days was considered as the lower detection limit. Due to high sensitivity of the method values were not zero for these specimens. Ag release of specimens with fluences of 1 × 1017 cm−2 and 5 × 1016 cm−2 showed an exponentially decrease up to five days from the beginning of the test (Fig. 6). Thereafter a steady state with minimal decrease of Ag release was achieved. Ag release of Ag-DLC-PE with a fluence of 1 × 1016 cm−2 was equal to the values of untreated PE and therefore below the lower detection limit.

Fig. 6.

Silver release kinetics of different Ag-DLC-PE (deposition method: PIII; fluence: 1 × 1017 cm−2, 5 × 1016 cm−2, and 1 × 1016 cm−2) and untreated PE samples

Discussion

Since the first applications of surgically-implanted materials in humans, bacterial infections have represented a common and challenging problem [1, 25]. More than 2.6 million orthopedic implants are performed annually in the United States, hence the incidence of implant-associated infections is also increasing [28]. Most important in the pathogenesis is the colonization of the device surface by formation of a biofilm [9, 29–31], at which Staphylococci and Streptococci are most frequently implicated as the etiologic agents [25, 32]. Recent strategies to lower peri-implant infection rates are based on the primary prevention of bacterial adhesion by non-adhesive coatings [33, 34] or impairment of bacterial survival and biofilm formation by surface coatings releasing non-antibiotic organic [35–37] and inorganic agents like Ag+, Cu++ or nitric-oxide [12, 38–40]. To our best knowledge, few attempts have been conducted so far to apply Cu- or Ag-DLC coatings on PE surfaces [24]. DLC surface modifications could be promising, based on the finding that DLC applied at PE is known to exhibit excellent wear behavior [18–20]. A previous study described significant antibacterial potency of Ag-DLC-PE [24], whether DLC coatings enriched with Cu provide the same ability is still unclear. Additionally, no data are available regarding comparison of different DLC deposition methods.

Ag seems to be of outstanding value in the prevention and treatment of implant associated infections [41–43]. Ag acts by binding to membranes, enzymes and nucleic acids. Consequently the respiratory chain is inhibited and therefore the aerobe metabolism of microorganisms disturbed [9]. Bacteria are quite susceptible to Ag with only negligible possibility of intrinsic resistance [12]. On the other hand, possible toxicity of silver-coated devices is still on debate, which limits its clinical use [10]. Therefore, in the present study one sample series was conducted with Cu-doped DLC coatings since some authors found Cu-ions having an outstanding position as an antibacterial but nevertheless bio-tolerant additive to coatings [14]. Besides these advantages a major disadvantage is the fact that Cu is difficult to implant on hard surfaces, e.g. titanium. The reason is its low solubility in ethanol-based solutions so that assembly of high dosage colloidal solutions for dip-coating is not possible. Cu highly tends to agglomerate in polyvinylpyrrolidone-matrix [44]. This would be limiting in the manufacturing process of DLC coated joint prostheses.

Our results demonstrated minor antibacterial effects on the surface of Cu- compared to Ag-DLC-PE samples (Table 1, Fig. 3). This finding was similarly described on other Cu-containing materials by other investigators [39]. We implanted Cu-ions in the same depth of the samples as Ag-ions. This is crucial in the assessment of antibacterial effects. If ion deposition within soft surfaces is performed with high energies (>80 keV) a rather deep deposition and concomitant slow or missing dissolution of ions onto the surface and into the surrounding medium is achieved. Consequently low bactericidal activity of these samples has to be expected [24]. Due to inferior antibacterial effects of Cu compared to Ag further testing was only conducted with Ag-DLC-PE.

Another finding in the present study was a deposition-depending antibacterial effect of Ag-DLC-PE. A wide variety of techniques have been employed for the synthesis of DLC coatings [19]. Among them, ion beam assisted deposition (IBAD) has great advantages for biomedical applications. It can produce thin films at low substrate temperature suitable for the majority of biomedical materials [45]. The most common used techniques for DLC processing are plasma-based, e.g. chemical vapor deposition (CVD) or physical vapor deposition (PVD) [46]. These methods are merely deposition techniques resulting in adhesive problems due to high internal stresses of DLC layers [47]. The methods of DLC processing in the present study (PIII and II) provide penetration of ions into the PE and concomitant DLC modification of these superficial layers. This fact diminished adhesion problems [48]. In this context, PIII is faster and more cost-effective compared to conventional II and allows DLC coating of complex-shaped surfaces, e.g. joint prostheses [49]. The resulting film properties after PIII treatment should be comparable to those achieved by direct II. On the other hand a clear superiority regarding the bactericidal potency of PIII-samples compared to II-samples was found in the present study. A possible explanation is a quicker dissolution of Ag-ions from the surface of PIII-samples. Therefore, release kinetics of Ag was investigated for these specimens. A high and earlier peak of initial dissolution of Ag for samples with high fluences (≥5 × 1016 cm−2) was found (Fig. 6). This “hit-hard-and-early-“effect is certainly crucial for the strong bactericidal potency of these coatings. In this context, a large clinical trial revealed no significant differences between silver-coated and uncoated medical devices [50]. One reason for this finding is that the tested coatings did not actively release silver ions. On the other hand, materials that actively release silver in the surrounding medium however have exhibited strong antibacterial activity [12]. Regarding the results of the present study, it is conceivable that samples with equal fluences but deposited with II would have had a lower peak of Ag release. This results in lower bactericidal potency within the first days due to lack of high concentrations of antibacterial ions on the sample’s surface and the surrounding medium. The fact that relatively low concentrated (fluence < 5 × 1016 cm−2) Ag-samples deposited with PIII did not release Ag can be explained with the “catching-effect” of low amounts of Ag in the polymer matrix [1]. In these circumstances no Ag-nanoparticles are formed and therefore Ag is trapped in superficial PE-layers without the possibility of dissolution.

This study involves several limitations. First, only two bacterial strains were used. Although the investigated strains are of major importance in periprosthetic joint infections, antibacterial effect against other bacteria has to be investigated in future studies. In fact, several studies confirmed even higher bactericidal potency of Ag against Gram-negative compared to Gram-positive bacteria [51, 52]. Second, Cu was only used in the first group. It remains unclear, whether Cu deposited with PIII would lead to increased antibacterial potency in these samples. However, antibacterial effects are caused by the intrinsic activity of the ion and this has been shown to be higher for Ag- compared to Cu-ions. Third, antibacterial effects on the sample surface could be supported by antiadhesive features of DLC alone. A significant antibacterial effect of DLC-PE without integrated Ag/Cu, on the other hand, could be ruled out in our previous experiments [53]. Fourth, no influence of Ag-DLC on osseointegration was investigated. A negative effect on eukaryotic cells in this context could be of major interest in the clinical use of this antibacterial coating even though PE is not used with direct bone contact. However, further investigations are needed in order to clear whether the antibacterial effect of Ag-DLC-PE surfaces is sufficient to avoid implant infection in-vivo.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings strongly support further investigation of Ag-DLC conversion of PE manufactured with PIII for prophylaxis of implant-associated infections. Antibacterial effectiveness of Ag-DLC-PE has been demonstrated. The suitability of this surface modification for biomedical applications will be confirmed by future studies.

Abbreviations

Ag, Silver; Ag+, silver ion; Ag-DLC, silver incorporated diamond-like carbon coating; Ag-DLC-PE, silver incorporated diamond-like carbon coating on polyethylene; Cu, copper; Cu-DLC-PE, copper incorporated diamond-like carbon coating on polyethylene; DLC, diamond-like carbon; DLC-PE, diamond-like carbon coating on polyethylene; PE, polyethylene; PJI, periprosthetic joint infections

Acknowledgements

We thank PD Dr. Thomas Grupp for providing the PE discs and Jutta Tübel for excellent technical help and advice.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

NH, SJ carried out the microbiological testing and drafted the manuscript. RK and BS provided DLC-processing of samples. HG, RB conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support

This work was supported by the „Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)“within the interdisciplinary project “Quantitative Evaluation der statischen und dynamischen Zelladhäsion und –aktivität an antibakteriellen DLC-Schichten für den biomedizinischen Einsatz” (BU 1154/2-1 and GO 1906/2-1, STR 361/18-1) and partially funded by the Wilhelm-Sander Foundation (Fördernummer: 2009.905.2), which is a charitable, non-profit foundation whose purpose is to promote cancer reasearch.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Zheng Z, Zara JN, Hsu C, Soofer DE, Lee KS, Siu RK, Miller LS, Zhang X, Carpenter D, et al. The antimicrobial and osteoinductive properties of silver nanoparticle/poly (DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-coated stainless steel. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8745–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank RM, Cross MB, Della Valle CJ. Periprosthetic joint infection: modern aspects of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. J Knee Surg. 2015;28:105–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzeng A, Tzeng TH, Vasdev S, Korth K, Healey T, Parvizi J, Saleh KJ. Treating periprosthetic joint infections as biofilms: key diagnosis and management strategies. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;81:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsen Ko LJ, Yoo JY, Maltenfort M, Hughes A, Smith EB, Sharkey PF. The Effect of Implementing a Multimodal Approach on the Rates of Periprosthetic Joint Infection After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:451–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gbejuade HO, Lovering AM, Webb JC. The role of microbial biofilms in prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop. 2015;86:147–58. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.966290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker RP, Furustrand Tafin U, Borens O. Patient-adapted treatment for prosthetic hip joint infection. Hip Int. 2015;25:316–22. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Liu Y, Guo J, Wu H, Wang J, Wu G. Biomaterials with Antibacterial and Osteoinductive Properties to Repair Infected Bone Defects. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.ter Boo GJ, Grijpma DW, Moriarty TF, Richards RG, Eglin D. Antimicrobial delivery systems for local infection prophylaxis in orthopedic- and trauma surgery. Biomaterials. 2015;52:113–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosheger G, Hardes J, Ahrens H, Streitburger A, Buerger H, Erren M, Gunsel A, Kemper FH, Winkelmann W, Von Eiff C. Silver-coated megaendoprostheses in a rabbit model--an analysis of the infection rate and toxicological side effects. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5547–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardes J, Ahrens H, Gebert C, Streitbuerger A, Buerger H, Erren M, Gunsel A, Wedemeyer C, Saxler G, Winkelmann W, Gosheger G. Lack of toxicological side-effects in silver-coated megaprostheses in humans. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoene A, Prinz C, Walschus U, Lucke S, Patrzyk M, Wilhelm L, Neumann HG, Schlosser M. In vivo evaluation of copper release and acute local tissue reactions after implantation of copper-coated titanium implants in rats. Biomed Mater. 2013;8:035009. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/8/3/035009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar R, Munstedt H. Silver ion release from antimicrobial polyamide/silver composites. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2081–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee D, Cohen RE, Rubner MF. Antibacterial properties of Ag nanoparticle loaded multilayers and formation of magnetically directed antibacterial microparticles. Langmuir. 2005;21:9651–9. doi: 10.1021/la0513306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidenau F, Mittelmeier W, Detsch R, Haenle M, Stenzel F, Ziegler G, Gollwitzer H. A novel antibacterial titania coating: metal ion toxicity and in vitro surface colonization. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:883–8. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-4422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cloutier M, Tolouei R, Lesage O, Levesque L, Turgeon S, Tatoulian M, Mantovani D. On the long term antibacterial features of silver-doped diamondlike carbon coatings deposited via a hybrid plasma process. Biointerphases. 2014;9:029013. doi: 10.1116/1.4871435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsikogianni M, Spiliopoulou I, Dowling DP, Missirlis YF. Adhesion of slime producing Staphylococcus epidermidis strains to PVC and diamond-like carbon/silver/fluorinated coatings. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:679–89. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-9678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwivedi N, Kumar S, Carey JD, Tripathi RK, Malik HK, Dalai MK. Influence of silver incorporation on the structural and electrical properties of diamond-like carbon thin films. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:2725–32. doi: 10.1021/am4003183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saikko V, Ahlroos T, Calonius O, Keranen J. Wear simulation of total hip prostheses with polyethylene against CoCr, alumina and diamond-like carbon. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1507–14. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dearnaley G. Diamond-like carbon: a potential means of reducing wear in total joint replacements. Clin Mater. 1993;12:237–44. doi: 10.1016/0267-6605(93)90078-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira LY, Kuromoto NK, Siqueira CJ. Treating orthopedic prosthesis with diamond-like carbon: minimizing debris in Ti6Al4V. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2014;25:2347–55. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinuber C, Kleemann C, Friederichs RJ, Haubold L, Scheibe HJ, Schuelke T, Boehlert C, Baumann MJ. Biocompatibility and mechanical properties of diamond-like coatings on cobalt-chromium-molybdenum steel and titanium-aluminum-vanadium biomedical alloys. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95:388–400. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertóti I, Mohai M, Tóth A, Ujvári T. Nitrogen-PBII modification of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene: Composition, structure and nanomechanical properties. Surf Coatings Technol. 2007;201:6839–42. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2006.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz F, Stritzker B. Plasma immersion ion implantation of polymers and silver–polymer nano composites. Surf Coatings Technol. 2010;204:1875–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.10.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrasser N, Jussen S, Banke IJ, Kmeth R, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Stritzker B, Gollwitzer H, Burgkart R. Antibacterial efficacy of ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene with silver containing diamond-like surface layers. AMB Express. 2015;5:64. doi: 10.1186/s13568-015-0148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmerli W, Ochsner PE. Management of infection associated with prosthetic joints. Infection. 2003;31:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-3079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tilton RC, Rosenberg B. Reversal of the silver inhibition of microorganisms by agar. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:1116–20. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.6.1116-1120.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:984–91. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmerli W, Moser C. Pathogenesis and treatment concepts of orthopaedic biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65:158–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vilain S, Cosette P, Zimmerlin I, Dupont JP, Junter GA, Jouenne T. Biofilm proteome: homogeneity or versatility? J Proteome Res. 2004;3:132–6. doi: 10.1021/pr034044t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwank S, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W, Blaser J. Impact of bacterial biofilm formation on in vitro and in vivo activities of antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:895–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter G, Dandy D. The natural history of the patient with an infected total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977;59:293–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B3.893507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groll J, Fiedler J, Bruellhoff K, Moeller M, Brenner RE. Novel surface coatings modulating eukaryotic cell adhesion and preventing implant infection. Int J Artif Organs. 2009;32:655–62. doi: 10.1177/039139880903200915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris LG, Tosatti S, Wieland M, Textor M, Richards RG. Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to titanium oxide surfaces coated with non-functionalized and peptide-functionalized poly(L-lysine)-grafted-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymers. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4135–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bumgardner JD, Wiser R, Elder SH, Jouett R, Yang Y, Ong JL. Contact angle, protein adsorption and osteoblast precursor cell attachment to chitosan coatings bonded to titanium. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2003;14:1401–9. doi: 10.1163/156856203322599734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verraedt E, Braem A, Chaudhari A, Thevissen K, Adams E, Van Mellaert L, Cammue BP, Duyck J, Anne J, Vleugels J, Martens JA. Controlled release of chlorhexidine antiseptic from microporous amorphous silica applied in open porosity of an implant surface. Int J Pharm. 2011;419:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baffone W, Sorgente G, Campana R, Patrone V, Sisti D, Falcioni T. Comparative effect of chlorhexidine and some mouthrinses on bacterial biofilm formation on titanium surface. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:445–51. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao L, Wang H, Huo K, Cui L, Zhang W, Ni H, Zhang Y, Wu Z, Chu PK. Antibacterial nano-structured titania coating incorporated with silver nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5706–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiedler J, Kolitsch A, Kleffner B, Henke D, Stenger S, Brenner RE. Copper and silver ion implantation of aluminium oxide-blasted titanium surfaces: proliferative response of osteoblasts and antibacterial effects. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34:882–8. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holt J, Hertzberg B, Weinhold P, Storm W, Schoenfisch M, Dahners L. Decreasing bacterial colonization of external fixation pins through nitric oxide release coatings. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25:432–7. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181f9ac8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morones JR, Elechiguerra JL, Camacho A, Holt K, Kouri JB, Ramirez JT, Yacaman MJ. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:2346–53. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taglietti A, Diaz Fernandez YA, Amato E, Cucca L, Dacarro G, Grisoli P, Necchi V, Pallavicini P, Pasotti L, Patrini M. Antibacterial activity of glutathione-coated silver nanoparticles against Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Langmuir. 2012;28:8140–8. doi: 10.1021/la3003838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hardes J, von Eiff C, Streitbuerger A, Balke M, Budny T, Henrichs MP, Hauschild G, Ahrens H. Reduction of periprosthetic infection with silver-coated megaprostheses in patients with bone sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:389–95. doi: 10.1002/jso.21498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz F, Thorwarth G, Stritzker B. Synthesis of silver and copper nanoparticle containing a-C:Hby ion irradiation of polymers. Solid State Sci. 2009;11:1819–23. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2009.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du C, Su XW, Cui FZ, Zhu XD. Morphological behaviour of osteoblasts on diamond-like carbon coating and amorphous C-N film in organ culture. Biomaterials. 1998;19:651–8. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(97)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Love CA, Cook RB, Harvey TJ, Dearnley PA, Wood RJK. Diamond like carbon coatings for potential application in biological implants ‚Äîa review. Tribology Int. 2013;63:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.triboint.2012.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter KC, Nastasi M, Munson C. Adherent diamond-like carbon coatings on metals via plasma source ion implantation. Surf Coat Technol. 1997;93:287–91. doi: 10.1016/S0257-8972(97)00062-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu XY, Chu PK, Ding CX. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng R-Rep. 2004;47:49–121. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2004.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mändl S, Krause D, Thorwarth G, Sader R, Zeilhofer F, Horch HH, Rauschenbach B. Plasma immersion ion implantation treatment of medical implants. Surf Coatings Technol. 2001;142–144:1046–50. doi: 10.1016/S0257-8972(01)01066-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riley DK, Classen DC, Stevens LE, Burke JP. A large randomized clinical trial of a silver-impregnated urinary catheter: lack of efficacy and staphylococcal superinfection. Am J Med. 1995;98:349–56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flores CY, Minan AG, Grillo CA, Salvarezza RC, Vericat C, Schilardi PL. Citrate-capped silver nanoparticles showing good bactericidal effect against both planktonic and sessile bacteria and a low cytotoxicity to osteoblastic cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:3149–59. doi: 10.1021/am400044e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN, Kim JH, Park SJ, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Park YK, Park YH, Hwang CY, et al. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2007;3:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harrasser N, Jussen S, Banke IJ, Kmeth R, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Stritzker B, Gollwitzer H, Burgkart R. Antibacterial efficacy of titanium-containing alloy with silver-nanoparticles enriched diamond-like carbon coatings. AMB Express. 2015;5:77. doi: 10.1186/s13568-015-0162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.