Summary

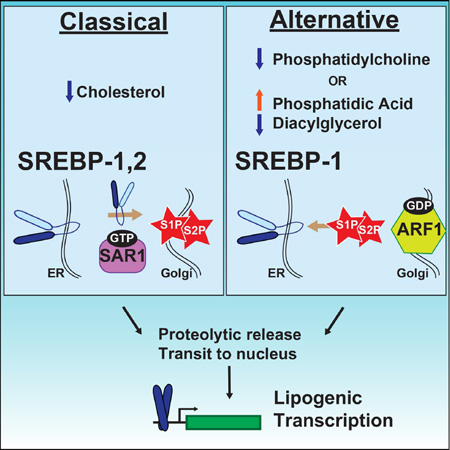

Lipogenesis requires coordinated expression of genes for fatty acid, phospholipid, and triglyceride synthesis. Transcription factors, such as SREBP-1 (Sterol regulatory element binding protein), may be activated in response to feedback mechanisms linking gene activation to levels of metabolites in the pathways. SREBPs can be regulated in response to membrane cholesterol and we also found that low levels of phosphatidylcholine (a methylated phospholipid) led to SBP-1/SREBP-1 maturation in C. elegans or mammalian models. To identify additional regulatory components, we performed a targeted RNAi screen in C. elegans, finding that both lpin-1/Lipin 1 (converts phosphatidic acid to diacylglycerol) and arf-1.2/ARF1 (a GTPase regulating Golgi function) were important for low-PC activation of SBP-1/SREBP-1. Mechanistically linking the major hits of our screen, we find that limiting PC synthesis or LPIN1 knockdown in mammalian cells reduces levels of active GTP-bound ARF1. Thus, changes in distinct lipid ratios may converge on ARF1 to increase SBP-1/SREBP-1 activity.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

SREBP transcription factors may be proteolytically activated in response to low cholesterol or by low phosphatidylcholine (PC) by distinct mechanisms. Smulan et al. find that SREBP-1 processing in low PC is linked to changes in phosphatidic acid, diacylglycerol or PC in microsomal membranes leading to decreases in active GTP-bound ARF1.

Introduction

Metabolic gene regulation is often connected to products or substrates in the pathway. In some cases, such as low-cholesterol stimulated maturation of SREBP (Sterol regulatory element binding protein) transcription factors, mechanisms have been described in detail. SREBPs reside in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as membrane intrinsic, inactive precursors (Osborne and Espenshade, 2009). Drops in intramembrane cholesterol promote transport of SREPB to the Golgi (Goldstein et al., 2006) where proteases release the transcriptionally active portion (Brown and Goldstein, 1997). SREBPs regulate genes required for fatty acid, TAG (triglyceride), PC (phosphatidylcholine) and cholesterol synthesis (Horton et al., 2002), therefore, it is not surprising that control of SREBP activity is complex and responds to a variety of metabolic signals. SREBP-2 is tightly linked to cholesterol synthesis, whereas the SREBP-1a/c isoforms have a broader roles (Horton, 2002). Using C. elegans and mammalian models, we previously found that low levels of SAM acted through PC to induce cholesterol-independent SREBP-1 processing (Walker et al., 2011). Instead of depending on COP II transit to the ER, low PC was associated with dissolution of Golgi markers, suggesting SREBP-activating proteases may cleave ER bound SREBP-1, as in Brefeldin-A mediated activation (DeBose-Boyd et al., 1999). However, regulatory factors linking PC to these processes were unclear.

To identify additional factors in this pathway, we performed a C. elegans RNAi screen using the SBP-1/SREBP-1 responsive reporter. Our genetic approach identified lpin1/LPIN1 and arf-1.2/ARF1, suggesting that like cholesterol-dependent regulation of SREBP-2, low-PC effects on SREBP-1 are linked to effects of membrane lipids on intracellular transport, however in this case, intermediates in the TAG/PC synthesis pathway, such as PA and DAG, may affect Golgi to ER COP I function.

Results

Targeted RNAi screen to reveal low-PC modulators of SBP-1

To identify components in low-PC activation of SBP-1/SREBP-1, we performed a targeted RNAi screen comparing activation of a SBP-1-dependent reporter, pfat-7::GFP, in wild type and low-PC conditions. fat-7 encodes a stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) regulated by SBP-1 (Yang et al., 2006). Depletion of PC synthesis enzymes (sams-1, pmt-1, cept-1, pcyt-1), stimulates SBP-1 and fat-7 levels increase (Walker et al., 2011) (Figure 1A). We focused on metabolic pathways producing or utilizing PC, genes involved in lipid-based signaling, and a subset of genes linked to COP I or II transport. Next, we selected an RNAi sublibrary from the ORFeome collection (Rual et al., 2004), the Ahringer library (Kamath et al., 2003), or constructed RNAi targeting vectors (Table S1). We screened for candidates satisfying two criteria: first, necessary for pfat-7::GFP induction in low-PC sams-1(lof) animals, and second, sufficient to activate pfat-7::GFP in wild type phospholipid levels (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Targeted RNAi screen to identify modulators of SBP-1/SREBP-1 activation in low PC conditions in C. elegans.

(A) Schematic representation of low-phosphatidylcholine (PC) based SBP-1/SREBP-1 activation in C. elegans. (B) Schematic representation of RNAi screen designed to distinguish factors necessary and sufficient for low-PC based SBP-1 activation (Classes 2,3) from those generally required for SBP-1 function (Classes 1,3). (C) Heat map showing genes which down regulate fat-7 expression in both pfat-7::GFP and sams-1(lof);pfat-7::GFP animals. (D) Heat map showing genes increasing fat-7 expression in pfat-7::GFP animals, while reducing GFP expression in sams-1(lof);pfat-7::GFP animals. (E) Color bar representing averaged GFP scores represented by yellow (high) and by blue (low). Epifluorescence imaging showing RNAi of Class 2/3 candidates in pfat-7::GFP (F) or sams-1(lof);pfat-7::GFP (G) in young adult C. elegans. Scale bar show 75 microns. See also, Table S1, Figure S1.

We screened four library replicates and divided candidates into four classes according to GFP expression and genotype (Figure 1B; Table S1). Class 1 or class 2 genes limited or increased pfat-7::GFP expression and comprised 49(23%) or 10(5%) of clones screened. Candidate class 3 genes were associated with decreases in sams1(lof); pfat-7::GFP (68 genes) and there were no genes that increased pfat-7::GFP in sams-1(lof) animals (class 4). Class 1 and class 3 genes are predicted to be generally important for SBP-1 function, and indeed include many regulators of classical SREBP-1 processing such as scp-1 (SCAP, SREBP cleavage-activating protein), and the COP II components such as sec-23, sec-24.1 and sar-1 (Figure 1C, red lettering). As in our previous data, PC synthesis genes (pcyt-1 and cept-1) (Figure 1D, red labeling) fell into class 2 (Walker, et al., 2011). Genes necessary for low-PC processing and sufficient to activate SBP-1 in normal PC (Figure 1D, red lettering) were predicted to lie in the intersection of candidate classes 2 and 3. The GTPase arf-1.2 was present in this category, as well a phospholipase C ortholog. However, the PA phosphatase lpin-1 (Reue, 2007) showed the most striking increase in pfat-7::GFP combined with decrease in sams-1(lof);pfat-7::GFP (Figure 1D–G Table S1).

Next, we used quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine expression of gfp, endogenous fat-7 and fat-5 (another SBP-1 responsive gene) in the reporter strain and also analyzed fat-7 and fat-5 expression in wild type animals. First, we confirmed that 5 of the top 10 class 1 genes were necessary for pfat-7::GFP mRNA expression (see Table S1; see column K–M for validation). For class 2 genes, we found that only lpin-1, arf-1.2 and plc-1 RNAi increased gfp, endogenous fat-7 and fat-5 mRNA levels (Figure S1B, D). lpin-1, arf-1.2 and plc-1 RNAi also decreased gfp levels in the low-PC sams-1(lof);pfat-7::GFP (Figure S1C, E). Finally, while lpin-1 and arf-1.2 RNAi increased endogenous fat-7 and fat-5 in wild type worms, plc-1 effects occurred only in the transgenic strain (Figure S1D). We also noted that sams-1(lof) animals with reduced lpin-1 showed additional phenotypes, including slowed development and synthetic lethality (Figure S1G).

The importance of lpin-1 for low-PC activation pfat-7::GFP prompted us to examine pathways producing the LPIN-1 substrate, PA. C. elegans contains multiple paralogs of PA synthesis genes (Figure S1A): three GPATs, acl-4, -5 and -6 and two AGPATs, acl-11 and acl-13 (Ohba et al., 2013). Our screen data showed that one GPAT (acl-4) and one AGPAT (acl-11) were required for pfat-7::GFP expression in wild type, but not in sams-1(lof) animals (Figure 1C). In validation assays, we found GFP was lower after acl-4 or acl-11 RNAi (Figure S2A), as were gfp and endogenous fat-7 mRNA levels (Figure S2B). pfat7::gfp or endogenous fat-7 gene expression was not altered by acl-4 and acl-11 RNAi in low-PC (sams-1(lof); pfat-7::GFP) conditions (Figure S2C, D).

sams-1 or lpin-1 RNAi reduce DAG and change PA/PC ratios in C. elegans microsomal membranes

Loss of sams-1 decreases PC and increases TAG (Ding et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2011), however, lpin-1 knockdown is predicted to affect PA and DAG (Figure S1A). To generate lipid profiles in membranes linked to SBP-1/SREBP-1 processing, we profiled microsomal lipids from sams-1 or lpin-1 RNAi animals. We validated fractionations by immunobloting with C. elegans ER or Golgi specific antibodies (Figure S3A). LC/MS analysis identified over 1600 lipid species in over 20 classes (Table S2). Principal component analysis shows that control, sams-1 and lpin-1 RNAi samples are distinct and that biological replicates are similar (Figure S3B). We analyzed the data in two ways: first, values for lipid species were totaled for each class and second, the distribution of species within each class was determined. In sams-1(RNAi) microsomal fractions, we found that TAGs as a class were increased and PCs as a class were decreased (Figure S2 C, D; see Table S2 for statistics), as in our previous studies analyzing whole worm extracts by GC/MS (Ding et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2011). Many other lipid species also changed (Figure S3E, Table S2), perhaps in response to synthetic links between PC and other lipids. We were surprised to see that DAG as a class was similar to wild type, however, many individual species shifted significantly lower and the distribution of species within the class differed significantly after sams1(RNAi) (Figure S3F, Table S2). This is in contrast to models for PC metabolism that predict increased DAG when PC synthesis is blocked (Sarri et al., 2011) and may reflect the specific nature of our assay.

lpin-1 RNAi, on the other hand, had fewer overall effects, primarily lowering levels of many DAG species and increasing multiple PA species (Figure S3F–I, see Table S2 for statistics), consistent with a role for lpin-1 as a PA phosphatase. Finally, we noted two major similarities in sams-1 and lpin-1 lipid profiles. First, ratios of PA/PC species were elevated, and second, the distribution of species within the DAG class shifted significantly lower. This is consistent with our genetic evidence implicating enzymes directly liked to PA, DAG, and PC in the regulation of pfat-7::GFP.

lpin-1 and arf-1.2 are important for low-PC effects on SBP-1

Increased fat-7 expression after lpin-1 RNAi suggests SBP-1 may be more active. To determine if maturation was stimulated, we examined subcellular localization of intestinal GFP::SBP-1 (Walker et al., 2010). Similar to sams-1 RNAi, knockdown of either lpin-1 or arf-1.2 resulted in increased nuclear levels of GFP::SBP-1 (Figure 2A), along with increases in fat-7 and fat-5 (Figure 2B). Interestingly, we noted that lpin-1 expression was slightly increased after sams-1 RNAi (Figure 2B); see also (Ding et al., 2015). Finally, depletion of PA synthesis enzymes acl-4 and acl-11 had opposite effects, decreasing nuclear SBP-1 (Figure S2E–G)

Figure 2. In C. elegans, lpin-1 and arf-1.2 RNAi increase nuclear localization of SBP-1::GFP and are important for lipid accumulation in sams-1(lof) animals.

(A) Confocal projection showing nuclear accumulation of intestinal GFP::SBP-1 after sams-1, lpin-1 or arf-1.2 RNAi. Scale bar for shows 10 microns. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showing upregulation of fat-5 and fat-7. Lipid accumulation when sams-1 and lpin-1 where co-depleted assessed by Sudan Black staining (C) with quantitation of percent of animals stained (D) or TAG level (E). Scale bar for Sudan Black shows 25 microns. For sams-1 and arf-1.2 co-depletion, Sudan Black staining and quantitation are in (F, G) and TAG measurements in (H). Number of animals is shown in parentheses. Error bars show standard deviation. Results from student’s T test shown by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005. See also Table S2, Figure S2.

Next, we performed Sudan Black staining to gauge size and distribution of lipid droplets and measured TAG for total levels. To avoid confounding results from the developmental delay of sams-1(lof); lpin-1(RNAi) animals (Figure S1G), PC production was rescued with choline until the L3 stage (Ding, et al 2015); growth without choline after L3 was sufficient to increase SBP-1-dependent gene expression (Figure S1H). lpin-1 RNAi animals appeared clear with slightly reduced Sudan Black staining (Figure 2C, D), consistent with reports of decreased Nile Red (Golden et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013), however TAG stores were not reduced in colorometric assays (Figure 2E) or microsomal extracts (Table S2, see tab:TG.class). This suggests other mechanisms may compensate for LPIN-1 function in TAG synthesis. Importantly, large lipid droplets in sams-1(lof) animals decreased upon lpin-1 RNAi and TAG returned close to wild type levels (Figure 2C–E). Thus, interference with both sams-1 and lpin-1 rescues effects of low-PC on stored lipids.

arf-1.2 knockdown also increased fat-7 expression and nuclear localization of GFP::SBP-1 (Figure 2A, B). Therefore, we assessed Sudan Black staining and TAG levels. arf-1.2(RNAi) worms had an increase in lipid droplets (Figure 2F, G), however, TAG levels were only slightly higher than wild type (Figure 2H), suggesting effects on droplets size and not total lipid levels. This is consistent with reports of ARF function in lipid droplet formation (Wilfling et al., 2014). In contrast, arf-1.2 RNAi reduced lipid droplet appearance, number and overall TAG levels in sams-1(lof) animals. Taken together, our C. elegans studies show that reducing function of LPIN-1, an enzyme converting PA to DAG, limits low-PC activation of SBP-1/SREBP. Thus, enzymes that produce or utilize PA may be a key to this mechanism.

LPIN1 knockdown is sufficient to activate mammalian SREBP-1 and necessary for low-PC effect

In mammals, interference with PC synthesis results in hepatosteatosis (Vance, 2014), as SREBP-1-dependent lipogenesis programs are stimulated (Walker et al., 2011). To determine if Lipin 1 was required for activation of mammalian SREBP-1 in this context, we depleted LPIN1 with siRNA. Like knockdown of PCTY1a/CCTa, the rate limiting enzyme in mammalian PC production, LPIN1 depletion increased levels of mature, nuclear SREBP-1 (Figure 3A–C). LPIN1 knockdown also increased nuclear localization and proteolytic maturation of a N-terminal HA tagged SREBP-1 (Figure 3D; Figure S4A, B). siRNA-mediated depletion was confirmed by qRT-PCR and immunoblots from Dignam extracts of HepG2 cells (Figure S4C, D).

Figure 3. siRNA knockdown of LPIN1 is similar to PCYT1 depletion, increasing SREBP-1 nuclear accumulation in human cells.

Confocal projections of immunostaining of endogenous SREBP-1 (A) or immunoblots (B, C) showing accumulation of the nuclear, processed form after siRNA of PCYT1a or LPIN1 in HepG2 cells. scr is the scrambled siRNA control and yellow lines show cell boundaries. FL shows the full length SREBP-1 precursor and M is the mature, cleaved version. (D) Confocal projections of HA-SREBP-1 levels after double knockdown of PCYT1 and LPIN1 in HepG2 cells with quantitation in (F). (E) Immunostaining and confocal projection of HepG2 cells shows increased nuclear accumulation of HA-SREBP-1 in cells treated with phosphatidic acid (PA). PA treatment decreases nuclear HA-SREBP-1 in siPCYT1a knockdown cells. Quantitation is in (G). Endogenous SREBP-1 localization is shown by confocal projections of immunostaining (H) or by immunoblot (I) after treatment of HepG2 cells with siRNA to ARF1. scr is scrambled control and yellow lines show cell outlines. (J) Immunoblots show decrease in ARF1 after siRNA treatment. Number of cells are shown in parenthesis. Results from student’s T test shown by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005. Scale bars show 10 microns. See also Table S3, Figure S4, 5.

To determine if LPIN1 function was important for low-PC effects on SREBP-1, we used siRNA to deplete both PCTY1a and LPIN1 in HA-SREBP-1 lines. For combined siRNA, we kept RNA amounts constant with scrambled control and achieved efficient knockdown for both PCTY1a and LPIN1 (Figure S4C). We found that nuclear HA-SREBP-1 localization was lost in PCTY1a/LPIN1 double knockdowns (Figure 3D, F), suggesting that as in C. elegans, LPIN1 knockdown abrogates the low-PC effect on SREBP-1. Similar effects were seen with endogenous SREBP-1 (Figure S4E, F).

Lipin 1 converts PA to DAG, thus lower activity predicts increases in PA (Takeuchi and Reue, 2009). To determine if exogenous PA could recapitulate LPIN1effects, we treated HA-SREBP-1 cells with PA and found that indeed, SREBP-1 nuclear accumulation increased (Figure 3E, G). Further paralleling LPIN1 knockdown, PA decreased nuclear SREBP-1 in PCTY1a siRNA cells (Figure 3E, G). Although effects of exogenous PA on cultured cells may be complex and have species dependent effects, changes in SREBP-1 maturation are consistent with effects of LPIN1 knockdown. We also investigated low-PC induced lipid droplet formation and found that, as in C. elegans, co-depletion of PCTY1a with LPIN1 restored lipid droplets to wild type levels (Figure S4G–I). Taken together, our results suggest that inhibiting LPIN1 expression or adding its exogenous substrate can reverse the effects of PCYT1a knockdown on SREBP-1.

Lipin 1 has been shown to inhibit SREBP-1 activity when mTORC1-dependent (mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex) phosphorylation decreases and it localizes to the nucleus, sequestering SREBP-1 at the nuclear membrane. However, mechanisms linking low-PC SREBP-1 activation to Lipin 1 appear distinct. First, SREBP-1 nuclear localization after PCTY1A or LPIN1 knockdown is nucleoplasmic and target genes are activated (see also (Walker et al., 2011)). Second, localization of endogenous Lipin 1(Figure S5A, B; specificity antibody shown in Figure S5C), or a transfected Flag-Lipin 1 (Figure S5D) is not changed after PCTY1A knockdown. Finally, fractionation experiments show similar levels of Lipin 1 isoforms in nuclear/ER and microsomal fractions in control and PCTY1a extracts (Figure S5E). Lipin 1 may also act in co-activation of β-oxidation genes (Reue and Zhang, 2008), however, these genes are not altered upon PCYT1a depletion (Figure S5F). Thus, mechanisms linking Lipin 1 and SREBP-1 in low PC appear distinct from mTORC1-mediated control of Lipin 1 localization or direct effects on gene regulation.

PCTY1a and LPIN1 knockdown affect ARF1 activity

Our previous studies found that low-PC or disruptions in ARF1 GEF(Guanine Exchange Factor) GBF1 induced maturation of SREBP-1 (Walker et al., 2011) and our C. elegans screen also implicated arf-1.2 in SBP-1 activation (Figure 1D, F; Figure 2A). To determine if this mechanism extended to mammalian cells, we examined SREBP-1 localization and processing in HepG2 cells after ARF1 siRNA and found that nuclear accumulation increased and processed SREBP-1 appeared at higher levels (Figure 3H–J).

The validated hits from our C. elegans screen strongly implicated enzymes that alter PA or DAG levels in low-PC mediated processing of SREBP-1. Interestingly, both PA and DAG have been reported to affect ARF1 function, interfering with COP I transport (Asp et al., 2009; Fernandez-Ulibarri et al., 2007; Manifava et al., 2001). Therefore, we asked if knockdown of LPIN1 or PCYT1a affected levels of active, GTP-bound ARF1 and found that, strikingly, levels were diminished in both instances (Figure 4A–C). As in our previous assays, double knockdown of LPIN1 and PCYT1a corrected defects (Figure 4D, E). Finally, we asked if exogenous PA would phenocopy LPIN1 knockdown and rescue siPCYT1a effects on GTP-ARF levels and found partial rescue of active ARF1 (Figure 4F, G).

Figure 4. Knockdown of mammalian PCTY1 or LPIN1 decreases ARF1 activity.

(A) Pulldown assays specific for GTP-bound ARF1 show significant decreases after LPIN1 or PCTY1a knockdown. Densitometry showing an average of 3 experiments for siLPIN1 or 5 experiments for siPCTY1a is shown in (B) and (C) respectively. Comparison of active ARF1 levels shown in a representative immunoblot (D) or by densitometry from immunoblots of the double knockdown of PCYT1a and LPIN1 (E). Assessment of active ARF1 levels after PCYT1a siRNA or treatment with PA shown by immunblot (F) or by densitometry (G). (H) Immunoblots of fractionated HepG2 cells comparing cytosolic (C) to microsomal (M) association of GBF1 or ARF1 after knockdown of PCYT1a or LPIN1. Calnexin shows membrane-associated fractions and β-actin confirms loading. For densitometry, values were normalized to vehicle treated scrambled (scr) expressing cells and represent three independent experiments. Error bars show standard deviation. Results from student’s T test shown by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005 compared to scrambled (scr) conditions. ns is “not-significant”.

Cytosolic membrane levels of PA (Csaki et al., 2014), DAG (Sarri et al., 2011), or PC (Vance, 2014) could be affected in either LPIN1 or PCYT1a knockdown. Interestingly, ARF1 activity depends on membrane recruitment of the GTPase itself along with membrane association of the GAP (GTPase Activating Protein, ARFGAP1) and GEF (GBF1) (Bankaitis et al., 2012; Lev, 2006; Spang, 2002). In addition, DAG levels may be important for ARFGAP1 association (Antonny et al., 1997; Bigay et al., 2003; Fernandez-Ulibarri et al., 2007). Therefore, we compared association of ARF1, GBF1 or ARFGAP1 with microsomal membranes after PCYT1a or LPIN1 siRNA. Strikingly, GBF1 association was broadly decreased, while ARFGAP1 and ARF1 did not change (Figure 4 H, I; Figure S5G, H). This suggests that local changes in membrane lipids occurring after PCYT1a or LPIN1 depletion may have profound effects on recruitment GBF1, leading to disruptions in ARF1 activity activating SREBP-1.

Discussion

Lipid storage requires coordinated production of fatty acids, phospholipids, TAGs and other complex lipids (Horton et al., 2002). Many of these lipids also function in membrane structure or as signaling effectors, thus regulators of lipogenesis may respond to various signals. Our screen identified lpin-1, a PA phosphatase, (Takeuchi and Reue, 2009) as an activator of SBP-1/SREBP-1. Although enzymatic activities of lipins suggest straightforward synthetic functions, they have diverse roles and broad physiological effects (Csaki et al., 2014). For example, the fld mouse model of LPIN1 deficiency has metabolic defects including fatty liver and lipodystrophy (Peterfy et al., 2001) and the SREBP-1 transcriptional target SCD1 is upregulated (Chen et al., 2008). Lipin 1 has also been reported to affect SREBP-1 activity through nuclear membrane sequestration (Peterson et al., 2011) or to act as a co-activator of β-oxidation genes with PPARα (Finck et al., 2006); however, neither of these activities was altered after PCYT1/CCTa knockdown. In this context, we hypothesize Lipin 1-dependent effects on SREBP-1 occur when changes in changes membrane lipids alter membrane:protein interactions and activity of GBF-1 and ARF-1.

Changes in PA, DAG, or PC within subcellular membranes could have multiple effects. However, our data suggested a connection to ARFs. Notably, several studies have found that DAGs are important for ARF1 function or for recruiting ARFGAP (Antonny et al., 1997; Bigay et al., 2003; Fernandez-Ulibarri et al., 2007; Randazzo and Kahn, 1994). However, we found that it was the ARF-GEF, GBF1, that bound less well to membranes after PCYT1 or LPIN1 knock down. Loss of GBF1 activates the unfolded protein response and promotes cell death in mammalian cells (Citterio et al., 2008), and defects in development and Golgi integrity in C. elegans (Ackema et al., 2013). However, larval growth arrest after gbf-1(RNAi) in our screen precluded analysis. A recent study has suggested that GBF1 is recruited to membranes in response to increases in ARF-GDP (Quilty et al., 2014). We hypothesize that local changes in ratios of PA to PC species or decreases in DAG species, as seen in our studies of C. elegans microsomes, limit GBF1 recruitment and prevent generation of GTP-bound ARF1. In this instance, there could be insufficient DAG for recruitment or changes in curvature predicted by a PA-rich membrane could disrupt membrane:protein interactions.

Finally, we have found that co-depletion of PC biosynthetic enzymes and lpin-1/LPIN1 returns SBP-1/SREBP-1 function to basal levels and restores TAG levels. In this case, inhibiting the PA to DAG transition could limit both TAG and PC. We hypothesize this allows levels to rebalance, restoring ARF1 function and baseline SBP-1/SREBP-1 activity. Thus, our results suggest SBP-1/SREBP-1 transcriptional programs favoring lipogenesis may be stimulated when the balance of PA, DAG or PC change within microsomal membranes.

Experimental Procedures

C. elegans: strains and RNAi constructs

Nematodes were cultured using standard C. elegans methods. For information on strains and RNAi constructs, see Table S2.

C. elegans: RNAi screen

L1 larva were plated into 96 well plates arrayed with RNAi bacteria and scored at the L4/young adult transition. Each well was given a score from −3 to +3 with 0 as no change in 4 independent replicates and scores were averaged. RNAi clones whose average scores were >0.7 or <−0.7 were selected as candidates for validation.

C. elegans: GFP visualization

pfat-7::GFP and SBP-1::GFP C. elegans strains were grown until the L4/young adult transition and images were acquired on a Leica SPE II confocal microscope. All images were taken at identical gain settings within experimental sets and Adobe Photoshop was used for corrections to levels across experimental sets.

C. elegans: Gene Expression Analysis

C. elegans at the L4/young adult transition were lysed and qRT-PCR analysis was performed as in Ding et al. 2015. Primers are available upon request.

C. Elegans: Lipid Analysis

C. elegans were grown on plates containing 30 mM choline until L2, washed, and transferred to plates without cholineuntil the second day of adulthood. Sudan Black staining was performed as in Ding, et al. 2015. Briefly, animals were dehydrated in ethanol, stained with Sudan Black, placed on agar pads and photographed in bright field microscopy with a Leica SPE II. Sudan Black staining was quantitated by blind scoring of more then 30 for of small, medium, or large lipid droplets. TAG levels were determined using a Triglyceride Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, 10010303) following manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitation of TAG levels, 2-tailed Students T tests were used to determine significance between three biological replicates. For lipidomic methods, see Supplemental methods.

Cell Culture: Media and Stable Cell Lines

HepG2 cells (ATCC, HB-8065) were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), Glutamine (Invitrogen), and Sodium Pyruvate (Invitrogen). HepG2 cells stably expressing human SREBP-1c were generated by transfection of a pCMV6 SREBP-1c with an N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag (Origene, RC208404) and selection with Geneticin (Invitrogen).

Cell Culture: Transfection and siRNA

siRNA oligonucleotides were transfected for 48 hours with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, 13778100) (see Table S2 for specific siRNAs). Cells were incubated for 16 hours in 1% Lipoprotein Deficient Serum (LDS) (Biomedical Technologies, BT907) and 25 µg/ml ALLN (Calbiochem) for 30 min prior to harvesting. For studies with co-depletion of PCYT1a and LPIN1, equal amounts of each siRNA or targeting plus scrambled were transfected.

Cell Culture: Gene Expression

Total mRNA was extracted from with Tri-Reagent according to manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma). qRT-PCR conditions were identical to C. elegans studies. For qRT-PCR studies, graphs represent representative experiments selected from at least three biological replicates. 2-tailed Students T-tests were used to compare significance between values with two technical replicates. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Lipid Vesicle formation

Lipid vesicles containing 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (PA) (Avanti Polar Lipids, 830855P) were prepared by water bath sonication as in (Zhang et al., 2012) and added at final concentrations of 100 µM during the 16 hour incubation in 1% LDS.

Immunofluorescence and Oil Red O staining

Transfected cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.5% NP-40 prior before blocking in 5% fetal bovine serum/ 0.1% NP-40 and antibody treatment. For Oil Red O, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, stained with Oil Red O (3mg/ml in 60% isopropanol) for 10 min and visualized. For quantification of antibody staining or lipid droplets, 10 individual focal areas were photographed, then scored blind for high, medium or low nuclear accumulation (antibody) or analyzed using BioPix iQ 2.1.4 (droplets). 2-tailed Students T tests were used to compare significance between the 10 photograhed areas and are representative of three biological replicates. All images within experimental sets were taken with a Leica SPE II at identical confocal gain settings and Adobe Photoshop was used for levels corrections.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were lysed by syringe in High Salt RIPA (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4; 400 mM NaCl; 0.1% SDS; 0.5% NaDeoxycholate; 1% NP-40; 1 mM DTT, 2.5 µg/mL ALLN, Complete protease inhibitors (Roche). Extracts were separated on Invitrogen NuPage gels (4–12%), transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with specified antibodies. Immune complexes were visualized with Luminol Reagent (Millipore). Densitometry was performed by scanning of the film, then analysis of pixel intensity with ImageJ software. Graphs show average of at least three independent experiments with control values normalized to one.

Cell Fractionation: HepG2

Transfected cells were resuspended in cold homogenization buffer (Microsome purification kit, Biovision) and dounced, then cleared briefly. Supernatants were centrifuged at 80,000g for 45 minutes. Pellets were collected as microsomal fractions with the supernatant designated as the cytosolic fraction.

Active Arf1 Analysis

Levels of active Arf1 were analyzed using an Active Arf1 Pull-Down and Detection Kit (ThermoSCIENTIFIC) following manufacturer’s instructions. Densitometry was performed by scanning of the film, then analysis of pixel intensity with ImageJ software. Graphs show average of at least three independent experiments with control values normalized to one.

Supplementary Material

Higlights.

A C. elegans screen finds lpin-1 and arf-1.2 as necessary for low-PC SBP-1 activation.

Depletion of mammalian LPIN1 and ARF1 activates SREBP-1 and rescues low-PC effects.

Levels of active ARF fall when PC synthesis is blocked or LPIN1 is depleted.

Blocking PC synthesis or LPIN1 siRNA decreases GBF1 association with microsomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Lambright and Stefan Taubert for reading of the manuscript as well as Drs. Marian Walhout (UMASS Medical School), Victor Ambros (UMASS Medical School), Michael Czech (UMASS Medical School), Michelle Mondoux (College of the Holy Cross) and members of their labs for helpful discussion. We also thank Dr. Michael Lee (UMASS) for advice on bioinformatics. Some C. elegans strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work was supported by the NIH through R01DK084352 to A.K.W.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CrediT Taxonomy

Conceptualization and Methodology A.K.W; Software, S.G., Y.J.K.E.; Validation, L.J.S, W.D., A.K.W.; Formal Analysis, L.J.S., A.K.W.; Investigation, L.J.S., W.D., A.K.W.; Writing-original draft, Writing-reviewing and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration and Funding Acquisition, A.K.W.

References

- Ackema KB, Sauder U, Solinger JA, Spang A. The ArfGEF GBF-1 Is Required for ER Structure, Secretion and Endocytic Transport in. PloS one. 2013;8:e67076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonny B, Huber I, Paris S, Chabre M, Cassel D. Activation of ADP-ribosylation factor 1 GTPase-activating protein by phosphatidylcholine-derived diacylglycerols. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30848–30851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asp L, Kartberg F, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Smedh M, Elsner M, Laporte F, Barcena M, Jansen KA, Valentijn JA, Koster AJ, et al. Early stages of Golgi vesicle and tubule formation require diacylglycerol. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:780–790. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankaitis VA, Garcia-Mata R, Mousley CJ. Golgi membrane dynamics and lipid metabolism. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R414–R424. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigay J, Gounon P, Robineau S, Antonny B. Lipid packing sensed by ArfGAP1 couples COPI coat disassembly to membrane bilayer curvature. Nature. 2003;426:563–566. doi: 10.1038/nature02108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Gropler MC, Norris J, Lawrence JC, Jr, Harris TE, Finck BN. Alterations in hepatic metabolism in fld mice reveal a role for lipin 1 in regulating VLDL-triacylglyceride secretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1738–1744. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.171538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citterio C, Vichi A, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Aponte AM, Moss J, Vaughan M. Unfolded protein response and cell death after depletion of brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein GBF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2877–2882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712224105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaki LS, Dwyer JR, Li X, Nguyen MH, Dewald J, Brindley DN, Lusis AJ, Yoshinaga Y, de Jong P, Fong L, et al. Lipin-1 and lipin-3 together determine adiposity in vivo. Mol Metab. 2014;3:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBose-Boyd RA, Brown MS, Li WP, Nohturfft A, Goldstein JL, Espenshade PJ. Transport-dependent proteolysis of SREBP: relocation of site-1 protease from Golgi to ER obviates the need for SREBP transport to Golgi. Cell. 1999;99:703–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W, Smulan LJ, Hou NS, Taubert S, Watts JL, Walker AK. s-Adenosylmethionine Levels Govern Innate Immunity through Distinct Methylation-Dependent Pathways. Cell Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ulibarri I, Vilella M, Lazaro-Dieguez F, Sarri E, Martinez SE, Jimenez N, Claro E, Merida I, Burger KN, Egea G. Diacylglycerol is required for the formation of COPI vesicles in the Golgi-to-ER transport pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3250–3263. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck BN, Gropler MC, Chen Z, Leone TC, Croce MA, Harris TE, Lawrence JC, Jr, Kelly DP. Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1alpha/PPARalpha regulatory pathway. Cell Metab. 2006;4:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden A, Liu J, Cohen-Fix O. Inactivation of the C. elegans lipin homolog leads to ER disorganization and to defects in the breakdown and reassembly of the nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1970–1978. doi: 10.1242/jcs.044743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, DeBose-Boyd RA, Brown MS. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins: transcriptional activators of lipid synthesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:1091–1095. doi: 10.1042/bst0301091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi.[see comment] Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev S. Lipid homoeostasis and Golgi secretory function. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:363–366. doi: 10.1042/BST0340363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manifava M, Thuring JW, Lim ZY, Packman L, Holmes AB, Ktistakis NT. Differential binding of traffic-related proteins to phosphatidic acid- or phosphatidylinositol (4,5)- bisphosphate-coupled affinity reagents. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8987–8994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba Y, Sakuragi T, Kage-Nakadai E, Tomioka NH, Kono N, Imae R, Inoue A, Aoki J, Ishihara N, Inoue T, et al. Mitochondria-type GPAT is required for mitochondrial fusion. EMBO J. 2013;32:1265–1279. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne TF, Espenshade PJ. Evolutionary conservation and adaptation in the mechanism that regulates SREBP action: what a long, strange tRIP it's been. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2578–2591. doi: 10.1101/gad.1854309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat Genet. 2001;27:121–124. doi: 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson TR, Sengupta SS, Harris TE, Carmack AE, Kang SA, Balderas E, Guertin DA, Madden KL, Carpenter AE, Finck BN, et al. mTOR Complex 1 Regulates Lipin 1 Localization to Control the SREBP Pathway. Cell. 2011;146:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilty D, Gray F, Summerfeldt N, Cassel D, Melancon P. Arf activation at the Golgi is modulated by feed-forward stimulation of the exchange factor GBF1. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:354–364. doi: 10.1242/jcs.130591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo PA, Kahn RA. GTP hydrolysis by ADP-ribosylation factor is dependent on both an ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein and acid phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10758–10763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reue K. The role of lipin 1 in adipogenesis and lipid metabolism. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;286:58–68. doi: 10.1002/9780470985571.ch6. discussion 68–71, 162–163, 196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reue K, Zhang P. The lipin protein family: dual roles in lipid biosynthesis and gene expression. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual JF, Ceron J, Koreth J, Hao T, Nicot AS, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Vandenhaute J, Orkin SH, Hill DE, van den Heuvel S, et al. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarri E, Sicart A, Lazaro-Dieguez F, Egea G. Phospholipid synthesis participates in the regulation of diacylglycerol required for membrane trafficking at the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28632–28643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang A. ARF1 regulatory factors and COPI vesicle formation. Current opinion in cell biology. 2002;14:423–427. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi K, Reue K. Biochemistry, physiology, and genetics of GPAT, AGPAT, and lipin enzymes in triglyceride synthesis. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2009;296:E1195–E1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90958.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE. Phospholipid methylation in mammals: from biochemistry to physiological function. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1838:1477–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Jacobs RL, Watts JL, Rottiers V, Jiang K, Finnegan DM, Shioda T, Hansen M, Yang F, Niebergall LJ, et al. A conserved SREBP-1/phosphatidylcholine feedback circuit regulates lipogenesis in metazoans. Cell. 2011;147:840–852. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Yang F, Jiang K, Ji J-Y, Watts JL, Purushotham A, Boss O, Hirsch ML, Ribich S, Smith JJ, et al. Conserved role of SIRT1 orthologs in fasting-dependent inhibition of the lipid/cholesterol regulator SREBP. Genes & development. 2010;24:1403–1417. doi: 10.1101/gad.1901210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfling F, Thiam AR, Olarte MJ, Wang J, Beck R, Gould TJ, Allgeyer ES, Pincet F, Bewersdorf J, Farese RV, Jr, et al. Arf1/COPI machinery acts directly on lipid droplets and enables their connection to the ER for protein targeting. eLife. 2014;3:e01607. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Vought BW, Satterlee JS, Walker AK, Jim Sun Z-Y, Watts JL, DeBeaumont R, Saito RM, Hyberts SG, Yang S, et al. An ARC/Mediator subunit required for SREBP control of cholesterol and lipid homeostasis. Nature. 2006;442:700–704. doi: 10.1038/nature04942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Wendel AA, Keogh MR, Harris TE, Chen J, Coleman RA. Glycerolipid signals alter mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) to diminish insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1667–1672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110730109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zou X, Ding Y, Wang H, Wu X, Liang B. Comparative genomics and functional study of lipid metabolic genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.