Abstract

Long-term peritoneal dialysis (PD) often results in the development of peritoneal fibrosis. In many other fibrosing diseases, monocytes enter the fibrotic lesion and differentiate into fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes. We find that peritoneal tissue from short-term PD patients contains few fibrocytes, while fibrocytes are readily observed in the peritoneal membrane of long-term PD patients. The PD fluid Dianeal (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) contains dextrose, a number of electrolytes including sodium chloride, and sodium lactate. We find that PD fluid potentiates human fibrocyte differentiation in vitro and implicates sodium lactate in this potentiation. The plasma protein serum amyloid P (SAP) inhibits fibrocyte differentiation. Peritoneal dialysis fluid and sodium chloride decrease the ability of human SAP to inhibit human fibrocyte differentiation in vitro. Together, these results suggest that PD fluid contributes to the development of peritoneal fibrosis by potentiating fibrocyte differentiation.

Keywords: Peritoneal dialysis, fibrosis, lactate, fibrocytes

For patients with end-stage kidney disease (1), peritoneal dialysis (PD) is the most cost-effective and easiest way to replace kidney function (2–5). Peritoneal dialysis fluids contain electrolytes to help maintain blood composition, an osmotic agent, and a pH buffer (3,4). Peritoneal dialysis fluid is injected via a permanent catheter into the peritoneal cavity (2,6). The peritoneal membrane acts as a dialysis membrane, allowing the removal of waste products from the body into the peritoneal cavity (4–6). Although PD has many advantages compared to other treatments, the development of tissue remodeling such as angiogenesis, fibrosis, and membrane failure is a debilitating disadvantage (2,4–8).

Peritoneal fibrosis is characterized by a thickening of the submesothelium, increased extracellular matrix deposition, the presence of myofibroblasts, and increased fibrotic (scar) tissue (2,4–8). Peritoneal fibroblasts are central to progressive fibrosis of the peritoneal membrane (9) and may arise from phenotypic transition of mesothelial cells (6) or local proliferation (10). During wound healing, and in other fibrosing diseases, blood monocytes enter the tissue and differentiate into fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes (11–14). Fibrocytes stimulate the proliferation of, and collagen production by, nearby fibroblasts (15). The plasma protein serum amyloid P (SAP) inhibits fibrocyte differentiation (14). While the presence of fibroblasts in peritoneal fibrosis has been well documented, the presence of fibrocytes has not (8,16–21).

The commonly-used PD fluid Dianeal (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) contains the electrolytes sodium, chloride, calcium, and magnesium, dextrose (D-glucose) as an osmolyte, and lactate as a buffer (5). Absorbed lactate from PD fluid is converted to bicarbonate in the body, allowing a lactate gradient to be maintained (22). The lactate in PD fluid also regulates the formation of glucose degradation products (GDPs) (4,22). Low-GDP fluids are associated with a decrease in peritonitis, but these studies did not report whether there was an effect on peritoneal fibrosis (4,7). Peritoneal dialysis fluid contains NaCl, and dietary NaCl is associated with fibrosis (23). We observed that NaCl potentiates human fibrocyte differentiation (24). Although the effects of GDPs in PD fluid have been studied (4,25,26), little has been done to determine the effects of the remaining components of PD fluid on fibrosis.

In this report, we show that there are increased numbers of fibrocytes in the peritoneal tissue of patients with long-term PD, and that this may be due to the PD fluid potentiating human fibrocyte differentiation.

Methods

Immunostaining

Peritoneal membrane biopsy samples were obtained from Wales Kidney Research Tissue Bank and were collected originally as part of the Peritoneal Membrane Biopsy Registry Study (27). Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded peritoneal membrane blocks were sectioned (5 μm) on a microtome. Collagen staining with picrosirius red and staining quantification were done as previously described (28). Immunostaining was done as previously described (29), using mouse anti-CD45RO (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and Cy3-labeled mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or rabbit anti-fibronectin antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 5 μg/mL. Anti-CD45RO antibodies were detected with 1 μg/mL anti-mouse-biotin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) and subsequently 1 μg/mL streptavidin-Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). Anti-fibronectin antibodies were detected with 1 μg/mL anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). Images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM 1200F camera or on a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal laser scanning microscope based on a Leica DM6000 upright microscope and analyzed using Leica Confocal Software.

Cell Culture and Fibrocyte Differentiation Assays

Human blood was collected from adult volunteers who gave written consent and with specific approval from the Texas A&M University human subjects Institutional Review Board. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated as previously described (24). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured in 96-well cell plates (Falcon) with PD fluid (132 mM sodium, 96 mM chloride, 3.5 mM calcium, 0.5 mM magnesium, 40 mM lactate, and 1.5% dextrose) or individual components of PD fluid (sodium chloride, calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, sodium lactate, or dextrose) in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium. One-molar solutions of individual components were prepared in RPMI-1640 or water and filter-sterilized as previously described (24). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured with PD fluid components as previously described (24). Serum amyloid P was from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA, USA). After 5 days, cells were fixed and fibrocytes were counted as previously described (24). CD14+ monocytes were isolated as previously described (13) and treated as above.

Collagen and DAPI Staining

Collagen staining of cultured PBMC was done as previously described (30,31) with the exception that the primary antibody was 2.5 μg/mL rabbit anti-collagen I (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). To count total cells, cell nuclei in plates from the fibrocyte differentiation assays were stained with 2 μg/mL DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and fluorescence in 4 fields of view per well was imaged using a 10x lens with an InCell 2000 (GE Healthcare, Pitcataway, NJ, USA). The nuclei in the images were counted with CellProfiler software (32).

Statistics

Fits to sigmoidal dose-response curves with variable Hill coefficients, IC50s, ANOVA, and t-tests were calculated with Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Long-Term PD is Associated with an Increase in Fibrocytes

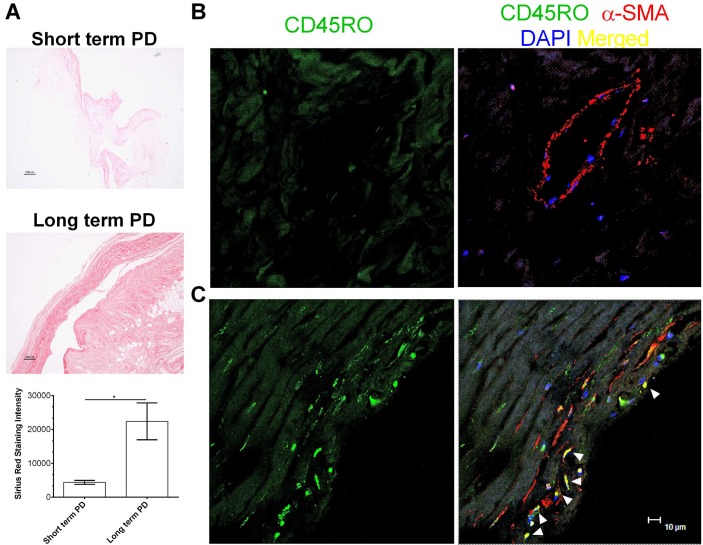

Peritoneal membranes from long-term PD patients exhibited thickening of the submesothelial compact zone, as previously described (6), and increased deposition of collagen (Figure 1A). Fibrocytes can be detected by co-localization of the hematopoietic marker CD45RO and the stromal marker α-smooth muscle actin (29). Compared to peritoneal membrane from short-term PD patients (Figure 1B), there were increased numbers of fibrocytes in the peritoneal membrane from long-term PD patients (Figure 1C). These data suggest that long-term PD is associated with an increase in fibrocytes in the peritoneal membrane.

Figure 1 —

Long-term PD is associated with an increase in fibrocytes. A) Sections from the peritoneum of patients on short-term and long-term PD were stained with picrosirius red, and the stain was quantified. Bar is 200 μM. * indicates p < 0.05 (t-test). Peritoneal sections from B) short-term and C) long-term PD patients were stained for the indicated markers. All images are representative of biopsy samples from at least 3 different patients of each type. Arrows indicate cells with significant overlap in staining with CD45RO and α-SMA. Bar is 10 μm. PD = peritoneal dialysis; α-SMA = α-smooth muscle actin.

PD Fluid Potentiates Fibrocyte Differentiation

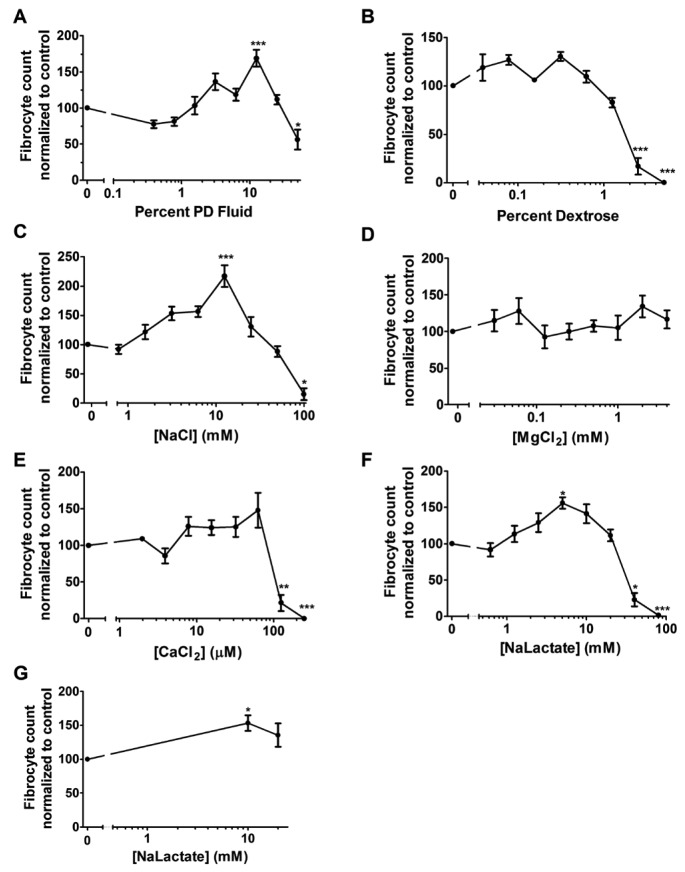

To determine if PD fluid affects the differentiation of monocytes into fibrocytes, human PBMCs were incubated with PD fluid added to RPMI for 5 days. The number of fibrocytes was increased in 12.5% PD fluid (Figure 2A). [Na+] and [Cl-] are 134 mM and 107 mM, respectively, in RPMI medium. Accounting for the dilution in RPMI medium, 12.5% PD fluid (16.5 mM sodium and an additional 12 mM chloride) corresponds to a [Na+] of 133.75 mM and a [Cl-] of 105.62 mM. These concentrations are lower than previous findings where NaCl potentiated fibrocyte differentiation (24). [Ca2+] and [Mg2+] are 0.42 mM and 0.4 mM, respectively, in RPMI medium. In dilutions of RPMI medium, 12.5% PD fluid corresponds to a [Ca2+] of 0.80 mM, a [Mg2+] of 0.41 mM, and 0.35% dextrose. The RPMI-1640 medium does not contain lactate; therefore the final concentration of lactate in 12.5% PD fluid is 5 mM. The number of fibrocytes was significantly decreased in the presence of 50% PD fluid added to the RPMI, in agreement with our observation that excessively high salt concentrations inhibit fibrocyte differentiation (24). These results indicate that PD fluid can potentiate fibrocyte differentiation.

Figure 2 —

Peritoneal dialysis fluid and some of its components potentiate the differentiation of fibrocytes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of A) PD fluid or B–F) PD fluid components added to RPMI. G) Purified monocytes were incubated with sodium lactate at the indicated concentrations. After 5 days, the cells were stained and counted. Values are mean±SEM, ≥3. *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 compared to control (1-way ANOVA, Dunnett's test). The absence of an error bar indicates that the error was smaller than the plot symbol. PD = peritoneal dialysis; SEM = standard error of the mean; NaCl = sodium chloride; MgCl2 = magnesium chloride; CaCl2 = calcium chloride; NaLactate = sodium lactate.

Some Components of PD Fluid Potentiate Fibrocyte Differentiation

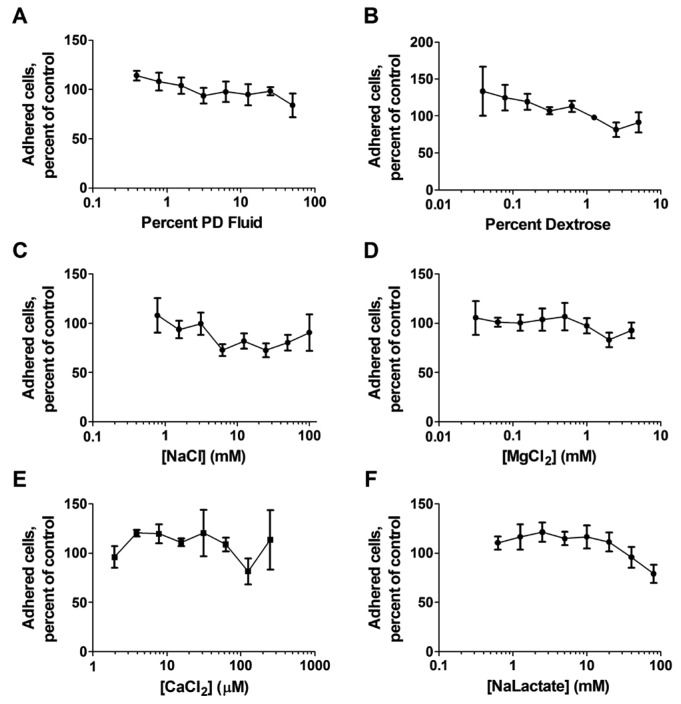

To determine which component(s) of PD fluid are responsible for the potentiation of fibrocyte differentiation, the individual components of PD fluid were added to RPMI with PBMCs for 5 days. An additional 12.5 mM NaCl in RPMI ([Na+] of 146.5 mM and [Cl-] of 119.5 mM) potentiated fibrocyte differentiation (24) (Figure 2C). These concentrations are similar to concentrations previously observed to potentiate fibrocyte differentiation (24) but are higher than the concentrations in 12.5% PD fluid/RPMI. Adding calcium chloride, magnesium chloride, or dextrose to RPMI did not potentiate fibrocyte differentiation (Figure 2B,D,E). Sodium lactate ([Na+] of 139 mM and a lactate concentration of 5 mM) potentiated fibrocyte differentiation (Figure 2F). Fibrocyte differentiation was potentiated from CD14+ monocytes for NaCl (24) and sodium lactate (Figure 2G). Fibrocyte differentiation was inhibited at higher concentrations of PD fluid components, including an additional 100 mM sodium chloride, 50 – 100 mM sodium lactate, 125 – 250 μM calcium chloride, or 2.5 – 5% dextrose (Figure 2B,C,E,F). One reason for the increase in fibrocyte numbers in the PBMC cultures could be an increase in the number of adherent cells. For PD fluid or any of its individual components, there was no significant increase or decrease in the number of adhered cells (Figure 3). Together these data indicate that some, but not all, of the components of PD fluid potentiate fibrocyte differentiation.

Figure 3 —

The effect of PD fluid components on total cells in the assay after fixation. Fixed cells from Figure 2 were stained with DAPI and counted. The percent of adhered cells compared to buffer alone is shown for the indicated components. Values are mean±SEM, n=3. The absence of an error bar indicates that the error was smaller than the plot symbol. PD = peritoneal dialysis; SEM = standard error of the mean; NaCl = sodium chloride; MgCl2 = magnesium chloride; CaCl2 = calcium chloride; NaLactate = sodium lactate.

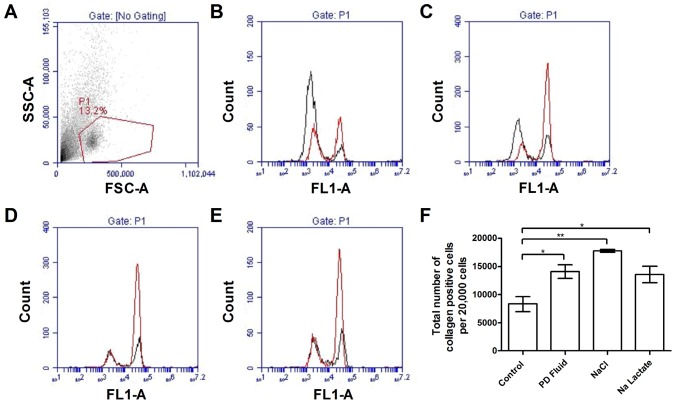

Collagen I is expressed by fibrocytes and used as a co-marker for these cells (30,33). To verify that the cells we counted were indeed fibrocytes, PBMC were cultured with PD fluid, sodium chloride, or sodium lactate added to RPMI for 5 days. The cells were then stained for collagen I and analyzed by flow cytometry. Compared to cells in medium alone, supplementation with 12.5% PD fluid, 12.5 mM sodium chloride, or 5 mM sodium lactate all significantly increased the number of collagen I-positive cells (Figure 4). These results support the observation that PD fluid, sodium chloride, and sodium lactate potentiate the differentiation of human PBMC into fibrocytes.

Figure 4 —

Peritoneal dialysis fluid, sodium chloride, and sodium lactate increase the expression of collagen. After a 5-day incubation, plated cells were stained for collagen I. A) Forward and side scatter properties of 5-day cultured cells. P1 outlined in red indicates a population that we previously observed to contain fibrocytes (31). Histograms show the fluorescent intensities of rabbit IgG control (black line) and collagen I (red line) for the P1 cells after incubation in B) media alone, C) 12.5% PD fluid, D) 12.5 mM sodium chloride, or E) 5 mM sodium lactate. F) The total number of collagen positive cells was calculated from the percentage of positive cells within the region P1. Values are mean±SEM, n≥3. * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01 (t-test); PD = peritoneal dialysis; SEM = standard error of the mean; SSC = side scatter; FSC = forward scatter; IgG = immunoglobulin G; FL = fluorescent intensity.

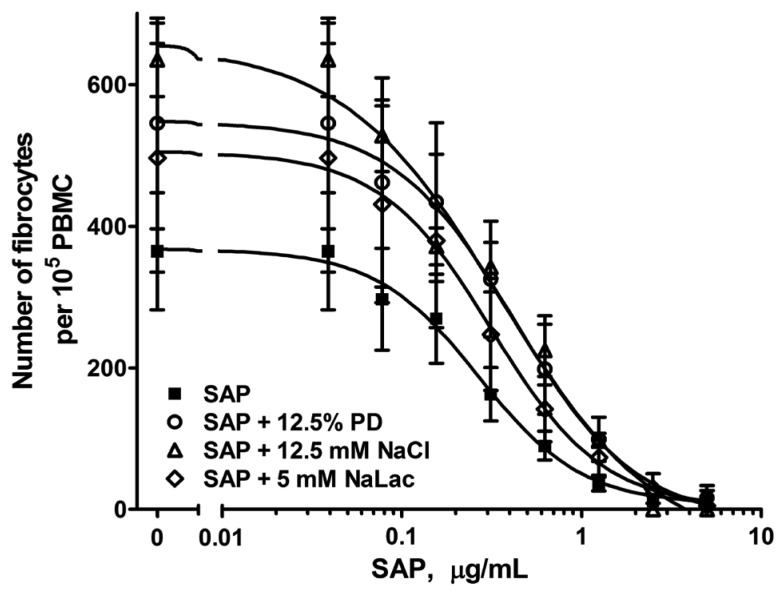

PD Fluid and Some of its Components Decrease the Ability of SAP to Inhibit Fibrocyte Differentiation

Serum amyloid P is secreted from the liver and inhibits fibrocyte differentiation (14,34,35). To determine if PD and its components affect the ability of SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation, PBMC were incubated with or without SAP in the presence of PD fluid, sodium chloride, and sodium lactate at the concentrations that caused the highest potentiation of fibrocytes. Although SAP was able to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation under all conditions examined (Figure 5), PD fluid and sodium chloride significantly increased the IC50 of SAP (Table 1). Although sodium lactate with SAP had an increased IC50 compared to SAP alone, the difference was not significant. These data indicate that PD fluid and sodium chloride interfere with the ability of SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation.

Figure 5 —

Peritoneal dialysis fluid and sodium chloride, but not sodium lactate, interfere with the ability of SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. Human PBMC were incubated in the presence or absence of 12.5% PD fluid, 12.5 mM sodium chloride, or 5 mM sodium lactate and the indicated concentrations of human SAP for 5 days. The number of fibrocytes were counted. Values are mean±SEM, n=3. Curves are fits to sigmoidal dose-response with variable Hill coefficients. SAP = serum amyloid P; PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PD = peritoneal dialysis; SEM = standard error of the mean; NaLac = sodium lactate; NaCl = sodium chloride.

TABLE 1.

PD Fluid and Sodium Chloride Increase the SAP IC50 for Inhibiting Fibrocyte Differentiation

Discussion

In this report, we found that the thickened and fibrotic peritoneal membranes observed in long-term PD patients contain fibrocytes, and that fibrocyte differentiation is potentiated by PD fluid and 2 of its components, sodium chloride and sodium lactate. In addition, PD fluid and sodium chloride reduce the ability of the endogenous fibrocyte differentiation inhibitor SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. Together, these results suggest that PD fluid potentiates fibrocyte differentiation and contributes to the PD fluid-associated fibrosis.

We previously observed that total concentrations of ~155 mM sodium or ~125 mM chloride potentiate fibrocyte differentiation (24). These concentrations are higher than in normal serum. Both sodium and chloride concentrations in Dianeal (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) PD fluid are slightly below those of serum (36). Therefore, the sodium or chloride content of PD fluid is not likely to be primarily responsible for the PD fluid potentiation of fibrocyte differentiation.

Fibrocyte differentiation was potentiated by 5 mM sodium lactate. An additional 5 mM sodium added to RPMI results in a [Na+] of 139 mM, which is similar to physiological levels. This, combined with previous work showing no fibrocyte potentiation by sodium below an additional 10 mM (24), indicates that the sodium from the 5 mM sodium lactate is not potentiating fibrocyte differentiation. Sodium lactate concentrations above 50 mM inhibited fibrocyte formation (Figure 2) consistent with our previous observations for > 50mM sodium (24). Thus, the inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation at high sodium lactate concentrations is likely due to sodium, not lactate. Lactate diffuses into the blood over the course of a dialysis exchange, following which it is converted to bicarbonate in the liver (36). The serum lactate concentration is ~1 – 2 mM (37). There is, therefore, a steady decrease in lactate concentration in the peritoneal cavity over the course of a typical 4-hour dialysis exchange. During PD, when peritoneal lactate concentrations drop to ~5 mM, we hypothesize that the lactate potentiates fibrocyte differentiation and thus fibrosis.

Both PD fluid and sodium chloride decreased the ability of SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. Sodium lactate did not significantly influence SAP activity, suggesting that the sodium lactate potentiation of fibrocyte differentiation could be through a mechanism independent of SAP inhibition. Together, our data suggest that peritoneal fibrosis may be alleviated in patients undergoing long-term PD by measures targeted at inhibiting fibrocyte differentiation, including changes in the composition of the dialysate and additives specifically targeting the fibrocyte differentiation pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor John Williams and the investigators and patients who enabled the formation of The Peritoneal Biopsy Registry. We also thank the blood donors and the phlebotomists at the Texas A&M Beutel Student Health Center.

REFERENCES

- 1. Heptinstall RH. Pathology of end-stage kidney disease. Am J Med 1968; 44:656–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krediet RT, Struijk DG. Peritoneal changes in patients on long-term peritoneal dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013; 9:419–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bargman JM. Advances in peritoneal dialysis: A review. Semin Dial 2012; 25:545–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan TM, Yung S. Studying the effects of new peritoneal dialysis solutions on the peritoneum. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27(Suppl 2):S87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Lima SM, Otoni A, Sabino Ade P, Dusse LM, Gomes KB, Pinto SW, et al. Inflammation, neoangiogenesis and fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis. Clin Chim Acta 2013; 421:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schilte MN, Celie JW, Wee PM, Beelen RH, van den Born J. Factors contributing to peritoneal tissue remodeling in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29:605–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tomino Y. Mechanisms and interventions in peritoneal fibrosis. Clin Exp Nephrol 2012; 16:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fielding CA, Topley N. Piece by piece: solving the puzzle of peritoneal fibrosis. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:477–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Witowski J, Jorres A. Peritoneal cell culture: fibroblasts. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:292–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen YT, Chang YT, Pan SY, Chou YH, Chang FC, Yeh PY, et al. Lineage tracing reveals distinctive fates for mesothelial cells and submesothelial fibroblasts during peritoneal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; (12):2847–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol 2001; 166:7556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reilkoff RA, Bucala R, Herzog EL. Fibrocytes: emerging effector cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:427–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pilling D, Vakil V, Gomer RH. Improved serum-free culture conditions for the differentiation of human and murine fibrocytes. J Immunol Methods 2009; 351:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Gomer RH. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. J Immunol 2003; 171:5537–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang JF, Jiao H, Stewart TL, Shankowsky HA, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Fibrocytes from burn patients regulate the activities of fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen 2007; 15:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2002; 110:341–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okada H, Inoue T, Kanno Y, Kobayashi T, Watanabe Y, Ban S, et al. Selective depletion of fibroblasts preserves morphology and the functional integrity of peritoneum in transgenic mice with peritoneal fibrosing syndrome. Kidney Int 2003; 64:1722–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jimenez-Heffernan JA, Aguilera A, Aroeira LS, Lara-Pezzi E, Bajo MA, del Peso G, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fibroblast subpopulations in normal peritoneal tissue and in peritoneal dialysis-induced fibrosis. Virchows Arch 2004; 444:247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aroeira LS, Aguilera A, Sanchez-Tomero JA, Bajo MA, del Peso G, Jimenez-Heffernan JA, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and peritoneal membrane failure in peritoneal dialysis patients: pathologic significance and potential therapeutic interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:2004–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McAnulty RJ. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: their source, function and role in disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 39:666–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aguilera A, Yanez-Mo M, Selgas R, Sanchez-Madrid F, Lopez-Cabrera M. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a triggering factor of peritoneal membrane fibrosis and angiogenesis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2005; 6:262–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Palmer BF. Dialysate composition in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. In: Henrich W, ed. Principles and practice of dialysis. 3 ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Susic D, Frohlich ED. Salt consumption and cardiovascular, renal, and hypertensive diseases: clinical and mechanistic aspects. Curr Opin Lipidol 2012; 23:11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cox N, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Nacl potentiates human fibrocyte differentiation. PLoS One 2012; 7:e45674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Witowski J, Bender TO, Wisniewska-Elnur J, Ksiazek K, Passlick-Deetjen J, Breborowicz A, et al. Mesothelial toxicity of peritoneal dialysis fluids is related primarily to glucose degradation products, not to glucose per se. Perit Dial Int 2003; 23:381–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kawanishi K, Honda K, Tsukada M, Oda H, Nitta K. Neutral solution low in glucose degradation products is associated with less peritoneal fibrosis and vascular sclerosis in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2013; 33:242–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williams JD, Craig KJ, Topley N, Von Ruhland C, Fallon M, Newman GR, et al. Morphologic changes in the peritoneal membrane of patients with renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:470–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pilling D, Gomer RH. Persistent lung inflammation and fibrosis in serum amyloid P component (APCs-/-) knockout mice. PLOS ONE 2014; 9:e93730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pilling D, Fan T, Huang D, Kaul B, Gomer RH. Identification of markers that distinguish monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. PLoS One 2009; 4:e7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. White MJ, Glenn M, Gomer RH. Trypsin potentiates human fibrocyte differentiation. PLOS ONE 2013; 8:e70795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cox N, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Distinct Fcγ receptors mediate the effect of serum amyloid P on neutrophil adhesion and fibrocyte differentiation. J Immunol 2014; 193:1701–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carpenter AE, Jones TR, Lamprecht MR, Clarke C, Kang IH, Friman O, et al. Cellprofiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol 2006; 7:R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Crawford JR, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Improved serum-free culture conditions for spleen-derived murine fibrocytes. J Immunol Methods 2010; 363:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pilling D, Roife D, Wang M, Ronkainen SD, Crawford JR, Travis EL, et al. Reduction of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by serum amyloid P. J Immunol 2007; 179:4035–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, Lee JM, Carlson S, Crawford JR, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors mediate ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:18284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Palmer BF. The effect of dialysate composition on systemic hemodynamics. Semin Dial 1992; 5:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wacharasint P, Nakada TA, Boyd JH, Russell JA, Walley KR. Normal-range blood lactate concentration in septic shock is prognostic and predictive. Shock 2012; 38:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]