Abstract

Background and objectives

Patients on in-center dialysis spend significant amounts of time in the dialysis unit; additionally, managing ESRD affects many aspects of life outside the dialysis unit. To improve the care provided to patients requiring hemodialysis, their experiences and beliefs regarding treatment must be understood. This systematic review aimed to synthesize the experiences of patients receiving in-center hemodialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We searched Embase, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Google Scholar, and reference lists for primary qualitative studies published from 1995 to 2015 that explored the experiences of adult patients receiving treatment with in-center hemodialysis. A thematic synthesis was conducted.

Results

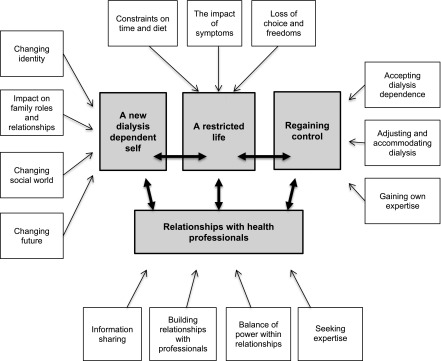

Seventeen studies involving 576 patients were included in the synthesis. Four analytic themes were developed. The first theme (a new dialysis–dependent self) describes the changes in identity and perceptions of self that could result from dialysis dependence. The second theme (a restricted life) describes the physical and emotional constraints that patients described as a consequence of their dependence. Some patients reported strategies that allowed them to regain a sense of optimism and influence over the future, and these contributed to the third theme (regaining control). The first three themes describe a potential for change through acceptance, adaption, and regaining a sense of control. The final theme (relationships with health professionals) describes the importance of these relationships for in-center patients and their influence on perceptions of power and support. These relationships are seen to influence the other three themes through information sharing, continuity, and personalized support.

Conclusions

Our synthesis has resulted in a framework that can be used to consider interventions to improve patients’ experiences of in-center hemodialysis care. Focusing on interventions that are incorporated into the established relationships that patients have with their health care professionals may enable patients to progress toward a sense of control and improve satisfaction with care.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, quality of life, patient satisfaction, patient experience, qualitative research, thematic synthesis, patient centered care

Introduction

Globally, the incidence of ESRD and the numbers requiring RRT are increasing (1). In the United States, the majority are treated with in-center hemodialysis (2). Patients receiving hemodialysis have a higher mortality rate and reduced quality of life compared with the general population (2,3). Although there has been some reported improvement in survival in recent years (2,4), studies have shown no improvement in quality of life (3). Deficiencies in satisfaction with hemodialysis care have also been shown (5–7). Satisfaction with care is unrelated to many of the clinical outcomes prioritized by physicians, and there is increasing evidence that outcomes commonly used in research and measured by registries may not be of importance to patients (6–9). There is growing interest in measuring outcomes that are of interest to patients through patient–reported outcome and experience measures. Studies using these tools report measures of quality of life, ratings of satisfaction with care, or severity of chosen symptoms; however, these attempts to quantify the experiences of patients do not provide the depth of insight into patients’ experiences that can be gained through qualitative methods.

Previous syntheses of qualitative research have explored the perspectives of patients with CKD on particular issues (including end of life care [10], vascular access [11], and dietary restrictions [12]) or specific patient groups, such as patients on peritoneal dialysis (13). Although most patients requiring dialysis treatment receive in-center hemodialysis, no previous qualitative synthesis has focused on their experiences. Through synthesizing studies, we aim to develop a comprehensive understanding of the influence that in–center dialysis dependence has on patients’ lives. This knowledge will better inform strategies to provide patient-centered care and patient-valued treatment and research outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This study is reported following the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research guidance (14).

Selection Criteria

Primary qualitative studies exploring the experiences of adults ages ≥18 years old receiving in-center hemodialysis were eligible for inclusion. Studies including patients receiving other forms of renal replacement, home hemodialysis exclusively, or the views of health professionals were excluded. Because the views of patients with CKD and their carers may differ (15), studies in which the views of carers were sought were excluded. To ensure relevance to current care, the search was limited to papers published in the past 20 years. Articles not written in English or for which the full text was not available were also excluded.

Literature Search

Medical subject heading terms and text words for hemodialysis and CKD were combined with terms found to be effective in identifying qualitative studies (16). The initial search findings were combined with additional terms to identify relevant studies (Supplemental Appendix). Searches were performed in Embase, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsychINFO in January of 2015. Google Scholar and reference lists of relevant papers and reviews were also searched. Titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (C.R.), and full texts of potentially relevant studies were obtained and assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers (C.R. and an independent reviewer).

Quality Appraisal

All papers were assessed against the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) qualitative research checklist (17). There is little consensus on which approach to appraising qualitative research offers the best validity (18); however, the CASP checklist is a recognized tool and has been used previously in systematic reviews of qualitative research (19,20). Two authors (C.R. and J.S.) independently appraised included studies using the CASP checklist, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. All studies satisfied the initial two screening questions of the CASP checklist and were considered relevant to the review (there was a clear statement of relevant aims and a qualitative methodology that was appropriate). Because there are currently no accepted methods for the exclusion of studies on the basis of their appraisal score, all studies were included in the synthesis (20,21).

Synthesis of Findings

This synthesis was approached from a critical realist perspective, which accepts the existence of an independent social world that can only be understood through the interpretations of both research participants and researchers (22). Thematic synthesis is not restricted in its use to a particular methodology, and it is an established method that aims to preserve a transparent link between primary studies and conclusions; it was, therefore, considered an appropriate method of synthesizing qualitative research for this review (21,23). All text within the results sections of the papers were coded line by line by C.R., and coding was then reviewed by J.S. Line by line coding allowed the translation of findings from one study to another (21). Codes were developed to represent new concepts until all of the data from the included studies had been coded. The final codes were then examined for similarities and grouped into 14 descriptive themes (Table 1) (21). These were analyzed to consider the effects of dialysis dependence on the participants’ lives to form analytic themes. Draft descriptive and analytic themes were developed by C.R. and presented to all members of the research team. Through discussion, the descriptive and analytic themes were developed and finalized. Analysis was managed using NVivo, version 10.

Table 1.

Codes contributing to descriptive and analytic themes

| Analytic Theme and Descriptive Themes | Contributing Codes |

|---|---|

| A new dialysis–dependent self | |

| Changing identity | Altered body image |

| Dependence and vulnerability | |

| Loss of identity | |

| Effect on family roles and relationships | Effects on family |

| Guilt | |

| Changing social world | Effect on involvement in social world |

| Lack of understanding from social world | |

| New social networks | |

| Changing future | Loss of future plans and ambitions |

| Uncertainty | |

| Facing the threat of death | |

| A restricted life | |

| Constraints on time and diet | Desire for quality of life |

| Restrictions imposed | |

| The effect of symptoms | Emotional effect |

| Physical symptoms | |

| Deterioration in health over time | |

| Fear of things going wrong | |

| Loss of choice and freedoms | Incarceration |

| Work of maintaining the dialysis regimen | |

| Time lost | |

| Regaining control | |

| Gaining own expertise | Testing boundaries |

| Using test results to make decisions | |

| Shared decision making | |

| Critical events as motivators | |

| Developing own knowledge and abilities | |

| Accepting dialysis dependence | Gift of life |

| Future hope | |

| Finding satisfaction in life | |

| Striving for normality | |

| Using time on dialysis | |

| Living on borrowed time | |

| Peer comparison | |

| Adjusting and accommodating dialysis | Gaining control |

| Improvement in health at initiation of dialysis | |

| Seeing the dialysis unit as a place of safety and security | |

| Time as an agent to normalization | |

| Release from burden of peritoneal dialysis | |

| Being realistic | |

| Relationships with health professionals | |

| Information sharing | Knowledge requirements |

| Uncertainty about the future | |

| Information sharing | |

| Building relationships with professionals | Continuity of care |

| Being seen as a whole person | |

| Balance of power within relationships | Asymmetry of power |

| Passivity | |

| Seeking expertise | Health care professionals’ knowledge and skills |

| Access to health care professionals |

Results

Literature Search

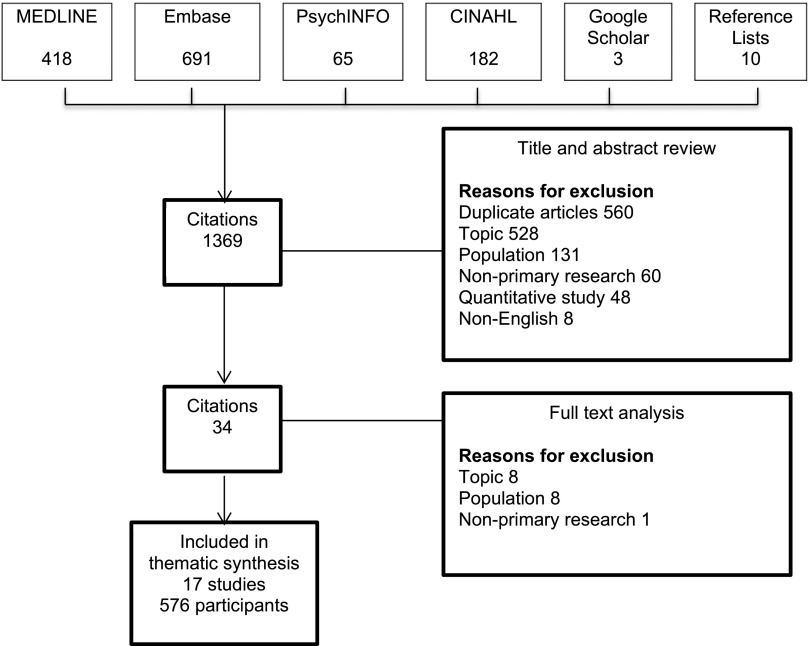

Our search yielded 1369 articles, from which 17 studies (24–40) involving 576 patients were included in the synthesis (Figure 1). The characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 2. The studies were published between 1998 and 2015 and included patients between 19 and 93 years old. Studies were conducted in Europe (n=9), North America (n=5), Australasia (n=2), and Asia (n=1).

Figure 1.

Results of search strategy and identification of included studies.

Table 2.

Included studies

| Study | Country | Year | No. | Age, yr | Sex | Duration of Dialysis | Population | Data Collection | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aasen et al. (24) | Norway | 2012 | 11 | >70 | 4 W/7 M | 4, ≤1 yr; 3, 1–2 yr; 4, 4–6 yr | Five hospital units | Interviews with open-ended questions | Critical discourse analysis |

| Al-Arabi (25) | United States | 2005 | 80 | >18 | Not reported | Not reported | Community–based outpatient dialysis center | Semistructured interviews | Naturalistic inquiry methods |

| Allen et al. (26) | Canada | 2011 | 7 | 38–63 | 3 W/4 M | Not reported | Two hospital units | Field observation, interviews, and focus groups | Participatory action research |

| Anderson et al. (27)a | Australia | 2012 | 241 | >20 | 116 W/125 M | Not reported | Nine hospital renal wards and 17 associated dialysis centers | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Axelsson et al. (28) | Sweden | 2012 | 8 | 66–87 | 3 W/5 M | 15 mo to 7 yr | Two university hospital dialysis clinics and two smaller satellite centers | Serial qualitative interviews | Phenomenologic hermeneutic method |

| Calvey and Mee (29) | Ireland | 2011 | 7 | 29–60 | Not reported | 1 mo to 5 yr | Not reported | Interviews using open-ended questions | Colaizzi phenomenologic method |

| Curtin et al. (31) | United States | 2002 | 18 | 38–63 | 8 W/10 M | 16–31 yr | Recruitment not clear | Semistructured interviews | Content analysis |

| Gregory et al. (30) | United States | 1998 | 36 | 19–87 | 18 W/18 M | Mean of 2.66 yr | One university teaching hospital unit | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| Hagren et al. (32) | Sweden | 2001 | 15 | 50–86 | 8 W/7 M | 6, <1 yr; 4, 1–3 yr; 5, >3 yr | One dialysis unit | Semistructured interviews | Content analysis |

| Hagren et al. (33) | Sweden | 2005 | 41 | 29–86 | 15 W/26 M | Not reported | Three hospitals | Semistructured interviews | Content analysis |

| Herlin and Wann-Hansson (34) | Sweden | 2010 | 9 | 30–44 | 4 W/5 M | Not reported | One public hospital and two private clinics | Interviews | Giorgi phenomenologic method |

| Kaba et al. (35) | Greece | 2015 | 23 | Mean age 62 | 8 W/15 M | Average 5.7 yr | Two hospital dialysis centers | Interviews | Grounded theory |

| Karamanidou et al. (36) | United Kingdom | 2014 | 7 | 32–68 | 4 W/3 M | 2–7 yr | One renal satellite unit | Semistructured interviews | Interpretive phenomenologic analysis |

| Lai et al. (37) | Singapore | 2012 | 13 | 39–63 | 7 W/6 M | 2–5 mo | One dialysis center | Semistructured interviews | Interpretive phenomenologic analysis |

| Mitchell et al. (38) | United Kingdom | 2009 | 10 | 2, 20–30; 1, 30–50; 5, 70–80; 2, >80 | 5 W/5 M | 2, <1 mo; 6, 1–3 mo; 2, 4–6 mo | One medium–sized renal unit | Semistructured interviews | Content analysis |

| Russ et al. (39) | United States | 2005 | 43 | 70–93 | 26 W/17 M | Not reported | Two dialysis units (one inner city and one private) | Interviews | Phenomenologic analysis |

| Shih and Honey (40) | New Zealand | 2011 | 7 | 46–77 | Not reported | 4–10 yr | One satellite dialysis unit | Semistructured interview | Heideggerian hermeneutic analysis |

W, women; M, men.

Demographic information relates to a larger study from which descriptions of those on hemodialysis are reported in this paper.

Quality Appraisal

Two papers satisfied all 10 items on the CASP checklist (17) (Table 3). One paper satisfied only five items; however, results were well illustrated through patient narratives. Most studies reported a sufficiently clear and rigorous approach to data analysis; however, in four studies, insufficient information was reported.

Table 3.

Results of Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklist appraisal

| Study | Clear Statement of Aims | Appropriate Methodology | Appropriate Design | Appropriate Recruitment Strategy | Appropriate Data Collection Strategy | Relationship between Researcher and Participants Adequately Considered | Ethical Issues Have Been Considered | Rigorous Data Analysis | Clear Statement of Findings | Value of Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aasen et al. (24) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes |

| Al-Arabi (25) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Allen et al. (26) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes |

| Anderson et al. (27) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes |

| Axelsson et al. (28) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Calvey and Mee (29) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes |

| Curtin et al. (31) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gregory et al. (30) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hagren et al. (32) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hagren et al. (33) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Herlin and Wann-Hansson (34) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kaba et al. (35) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Karamanidou et al. (36) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lai et al. (37) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mitchell et al. (38) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Russ et al. (39) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Unsure | No | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes |

| Shih and Honey (40) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Synthesis

Analysis resulted in 14 descriptive themes, which contributed to four analytic themes: a new dialysis–dependent self, a restricted life, regaining control, and relationships with health professionals. The descriptive themes identified in each study are shown in Table 4. Selections of quotes to illustrate each theme are given in Table 5.

Table 4.

Themes identified in each study

| Themes | Aasen et al. (24) | Al-Arabi (25) | Allen et al. (26) | Anderson et al. (27) | Axelsson et al. (28) | Calveyand Mee (29) | Curtin et al. (31) | Gregory et al. (30) | Hagren et al. (32) | Hagren et al. (33) | Herlin and Wann-Hansson (34) | Kaba et al. (35) | Karamanidou et al. (36) | Lai et al. (37) | Mitchel et al. (38) | Russ et al. (39) | Shih and Honey (40) | Total No. of Extracts | No. of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing identity | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 70 | 16 |

| Effect on family roles and relationships | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 44 | 13 |

| Changing social world | 0 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 61 | 16 |

| Changing future | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 60 | 11 |

| Constraints on time and diet | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 63 | 12 |

| The effect of symptoms | 2 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 15 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 106 | 16 |

| Loss of choice and freedoms | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 5 | 59 | 14 |

| Gaining own expertise | 7 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 64 | 14 |

| Accepting dialysis dependence | 1 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 12 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 7 | 128 | 16 |

| Adjusting and accommodating dialysis | 0 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 39 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 19 | 5 | 152 | 16 |

| Information sharing | 10 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 90 | 16 |

| Building relationships with professionals | 7 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 67 | 13 |

| Balance of power within relationships | 18 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 75 | 8 |

| Seeking expertise | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 7 |

Numbers refer to the numbers of extracts coded at each theme in the included papers.

Table 5.

Illustrative quotations

| Theme | Illustrative Quotation |

|---|---|

| A new dialysis–dependent self | |

| Changing identity | “I think dialysis is a detriment to maturity. I think you are placed over and over again in a dependent situation where you re-enact childlike relationships. From the machine to the staff, to the medical system, to the system that makes it all run, you know.” (31) |

| “There are a lot of things that we (dialysis patients) need to sacrifice. You cannot work, you cannot offer anything to your family.” (35) | |

| “Looking at their (established patients’) scars, I feel so scared. How do you expect me to go out in the public? I hide myself.” (37) | |

| Effect on family roles and relationships | “My wife would have preferred it in another way. To go out, to go to a tavern, to be able to go on holidays. It’s not only that you suffer, but you also make others suffer.” (35) |

| “I don’t want to start leaning on [my daughter]…I don’t find it easy, to be honest…I don’t want to make her life a misery.” (38) | |

| “I think that I am going to give a lot of trouble to my siblings, giving a lot of problems to your loved ones. They have to take time off (work) to do this and that for me…so I became a burden.” (37) | |

| Changing social world | “A lot of times your friends, your so-called friends, they don’t really have time for you, you know, ‘cause they go on with their own lives and you know you’re sitting around feeling tired. So that’s not a good feeling. Lots of times friends drop you when you can’t do anything.” (25) |

| “I cannot meet my friend John any more. Because I cannot eat, I cannot drink, and I think to myself if I go out with John who drinks and eats, I will be tempted and eventually drink. And I did this once, I drank three ouzos. And the result was I had to go home and collapse. So I cannot socialize with him.” (35) | |

| “I got used to coming here and it is necessary for me to come, to meet with these fellows and the staff.” (35) | |

| Changing future | “Now there is a lack of purpose…I have nothing to look forward to at the moment.” (37) |

| “How long will I live? It was the only thing I thought of—how long could one live with dialysis.” (32) | |

| “It has a hold on my life since I can’t plan ahead and say, ‘this is for sure.’” (31) | |

| A restricted life | |

| Constraints on time and diet | “Time is the worst part of it, because it takes too much time. From you, that is. You can’t do anything spontaneous, you become very tied down.” (33) |

| “If you are supposed to really follow that regime, I would rather cut a couple of years off my lifespan…There is almost nothing you could eat…I certainly don’t become worse/more ill because of that…With moderation of course, you see, it can’t be like you can’t take even a slice of bread with cheese or two during the day…That much I don’t think it means…I don’t say that I just don’t care, you see, but they observe those test reports then…phosphate and…calcium, perhaps, but then I get scolded a bit…They say that now you have to pull yourself together; this doesn’t go well. Now you destroy your years…but this is my choice…My wife was really confused in the beginning and just tried to take care and follow those lists. ‘We don’t do it,’ I said…I am not able to do this.” (24) | |

| The effect of symptoms | “Itching is…the way it’s been for the last couple of years makes me so depressed, you couldn’t understand. I almost jumped the other night—from the balcony. If it hadn’t been for my wife, I would have jumped. That’s how tired I am of it.” (33) |

| “This disease is very difficult, and no matter how hard you try, no matter how much strength you have, you will be weighed down with anxieties and get depressed. You are losing your self-control. I personally very often feel depressed, because I asked ‘why me?’” (35) | |

| Loss of choice and freedoms | “It is mostly a mental strain. After all, I have no pain then, but one feels like being put a little bit into prison, if one could use an ugly word like that.” (24) |

| “Having to be here 3 days a week is what I call a ‘command performance,’ no sooner do I start feeling better then I’m anticipating coming back again the next day. But there’s no choice, no modifying the experience.” (39) | |

| Regaining control | |

| Gaining own expertise | “Now when I understand the machine, what the machine really does, I can go in and change the parameter…that makes me feel like I am contributing to my treatment.” (34) |

| “You’re the doctor. I’m the patient, and let’s see how we can work this together. I want to be an influence on that decision. I want to help make the decisions, because I think I have a lot of input on my situation.” (26) | |

| Accepting dialysis dependence | “It’s a very different life, but I am willing to live it. I am willing to face whatever this different life brings about. I’m very aware of the drastic change in lifestyle…I cannot go back to the way it used to be…It’s like I have—I’ve lived two lives. One life when I was healthy and then this life with this illness.” (31) |

| “So I’m just really, really lucky, or I could be pushing up the daisies.” (38) | |

| “When I got sick and started with hemodialysis, I felt that I had to use the time. I started to study, and therefore, I have a life outside the dialysis. Now the dialysis is just a little part of my whole life, and the other is with my studies, that is the real me…The dialysis is just something that I do in between.” (34) | |

| Adjusting and accommodating dialysis | “It’s hard at first but you get used to it…if people are socializing and you can’t maybe have as much as them or…you can’t do what they are doing…but you have got to be grown up about it and realize well it’s one of those things where you have just got to put up with so…it’s hard but it’s…you just have to get on with it…‘Cause I’ve been doing it for so long now…it’s more natural now than if I was, you know, not ill.” (36) |

| “I think you’ve got to be realistic…I’ve just got to readjust my life and do what I can.” (38) | |

| Relationships with health professionals | |

| Information sharing | “[Doctors] think you don’t know what you are talking about. You’re not supposed to question.” (30) |

| “I want more information…Nurses do not tell me anything, other than the blood percentage…They could talk more about the illness and how it develops.” (24) | |

| “I can’t fathom it. I can’t look at my kidney, put it in my hand, and examine it myself. Why do I have to be on dialysis? What is kidney disease? How much of it [i.e., the disease] do I have to have before I need to be on dialysis? I ask these questions, but their only answer is to tell me to be here, to take water out of me. But that’s not an answer! I’m left dangling.” (39) | |

| Building relationships with professionals | “When I first started the dialysis, I was crying a lot. It was the head nurse who helped me to go through it, and she was there for me listening to my problems. Without her, I couldn’t continue.” (35) |

| “The personal chemistry must work for me…otherwise they are not allowed to canalize my fistula…[laughs]…I must have faith in that person, faith is very important.” (34) | |

| “They make one round, we only have it on Tuesdays, but then, we also go through everything once a month with the nurse and the doctor, that’s fantastic. That creates more of a personal relationship, there’s a little chatting about all sorts of things as well, at least when I'm sitting there.” (32) | |

| Balance of power within relationships | “You’re [doctor] not listening to the whole situation. You took a piece of it, made your analysis, made your decision, and you’ve moved on. But I’m still here living with whatever you left me with.” (26) |

| “If you come in and need a lot of drainage (ultrafiltration), they say ‘why do you need so much’ and start nagging me. Well, I know that I’ve been bad, but it’s impossible to stop yourself when you’re thirsty. I’ve told them ‘would you last on 5 dl a day?’; then they’ll tell me ‘but we’re healthy!’ As if I didn’t know.” (33) | |

| Seeking expertise | “I get so nervous when there are new nurses that are supposed to learn…they really don’t know how to do it, so they talk to themselves to remember, and then you get nervous yourself. Then I start to think: do they really put the tubing right? So then I get a little bit worried.” (34) |

| “But the fact of the matter is that if someone can’t get my needle in place—which actually does happen. Some people can’t do it at all. But then there are those who get it right every time.” (33) | |

| “In my experience, you don’t see many doctors…Most of them, I must say, they all know their work, they’re all good…if you can get them to come in to you.” (30) |

A New Dialysis–Dependent Self.

Changing Identity.

When commencing hemodialysis, some participants struggled with feelings of vulnerability and their dependency on both dialysis treatment and caregivers (24,26,28–32,35–40). The “assembly line” (26) nature of dialysis and lack of interest shown by staff could result in a loss of personal identity (24,26,28,35). Interference with earlier roles in society and social networks could also affect identity. Those required to give up employment reported this affected their sense of self as reliable and able to provide for their families (29,35,40). Additionally, dialysis affected the physical self through the creation of vascular access and other changes in appearance (25,29,36,37,39).

Effect on Family Roles and Relationships.

Participants expressed frustration, because dialysis required relocation or reduced the time and energy available to care for family members or carry out family duties (27–29,35). Some participants were now dependent on family for care or assistance and worried that they had become a burden to them (28–30,37,38). Participants who thought their dialysis dependence had restricted their families’ activities, such as holidays, also reported guilt (29,30,35).

Changing Social World.

Dietary and fluid restrictions, time spent on dialysis, and symptoms, such as fatigue, affected participants’ abilities to engage in previously enjoyed social activities (28,29,32,33,35,36,39,40). Some participants were reluctant to discuss dialysis dependence with others and perceived that they lacked understanding and compassion (25,27,31,32). Consequently, this resulted in difficulties maintaining social connections and friendships. However, the dialysis unit could also provide a new social framework through the development of friendships with staff and patients (26,28–30,34,35,38).

Changing Future.

When dialysis commenced, participants reported that they lost ambitions for the future, such as traveling and enjoying retirement (28,29,37,39). With dependence on dialysis, they were confronted with their own mortality (28–32,35,37,39), and this could be reinforced by the deaths of other patients in the dialysis unit (30,31,39). The future became uncertain, because they feared complications or premature death (28–31,34,35,39). Those waiting for a transplant also had to cope with the uncertainty of whether they would receive a kidney (31,32,34). Many participants described feeling unable to plan for the future and consequently, chose to “live in the moment” (28,30–32,36).

A Restricted Life.

Constraints on Time and Diet.

The scheduling and time required for dialysis restricts opportunities for employment, holidays, and social activities. Additionally, patients have fluid and dietary restrictions to which they are expected to adhere. These restrictions were often cited as sources of distress and adversely affected quality of life (24,25,28–31,33,35–37,39,40). Participants described weighing up adherence to these restrictions against effects on their quality of life (28,30,35–37,39).

The Effect of Symptoms.

Some participants reported physical symptoms, such as fatigue and pain (24,25,27–30,32–37,39,40), or emotional symptoms, including depression, anger, and isolation (24,27–30,32–40). Physical symptoms, such as fatigue, were seen to further restrict the opportunities to participate in desired activities (21,24,29,30,33) and had deleterious effects on mental wellbeing (23,24,29,33). Many symptoms were seen to result from or be exacerbated by dialysis, and some expressed anxiety about the deterioration in health that they experienced, despite ongoing dialysis treatment (30,31,35,39).

Loss of Choice and Freedom.

Some participants associated the need for dialysis with feelings of incarceration and powerlessness (24,25,28,29,32,34–36,39). They reported a loss of freedom to live life as they desired. Maintaining the dialysis regimen became a job that they had no choice but to do (28,31,33,34,36,39,40). Participants described losing time not only to having treatment but also, traveling, waiting, and recovering from their treatment (28–35,37,39,40).

Regaining Control.

Gaining Own Expertise.

With time, participants developed their own knowledge and abilities, and this was seen as important for regaining control (26,28–31,34,36). For some, this knowledge came through testing boundaries set by health professionals (24,26,27), whereas others reported that professionals facilitated their knowledge acquisition (30,33). Participants stressed the importance of their expertise being acknowledged by professionals to allow shared decision making (24,26–28,32,34,38–40). Making their own treatment decisions (26,28,32) or developing confidence in staff so that decisions could be entrusted to them was seen as an important way in which control could be gained (28).

Accepting Dialysis Dependence.

Participants reported differing routes to acceptance; for some, it was resignation that there was no other option to stay alive (27,28,30,36,38,39), whereas others chose to see the positives and viewed dialysis as a “gift” (25) providing life (25,29–31,35,38,40). Support from family, friends, and professionals was important in coming to this acceptance (30,37,40). Some were able to find optimism and hope for the future, and this was seen to facilitate acceptance (28,31,35). For many, hope was related to future transplantation (29,30,32,34–37).

Accommodating Dialysis.

Some participants found that they were able to adjust to life on dialysis. They reported the importance of adapting activities around dialysis and making the most of the time when not at the dialysis unit (21,27,28,30,32,34,35). Others felt it was important to use the time spent on dialysis for activities, such as study (30,35). The process of adjustment required participants to change their personal expectations (30,31,35,38,39) and was an ongoing process as new problems and changes in health were encountered (30,31).

Relationships with Health Professionals.

Information Sharing.

Some participants wanted more information from their health care providers (24,26,27,29,30,33,36). They thought information was not given freely or was kept from them (26,27,38). This contributed to uncertainty and conflicted with attempts to obtain control (24,26–28,36,39). Some were reluctant to ask questions or worried that this would be seen as complaining (24,27,28,40). As experts in their life circumstances, participants wanted to be listened to and involved in decisions about their care (24,26,28,30).

Building Relationships with Health Professionals.

Because of the frequency of contact with professionals on the dialysis unit, participants built relationships with staff, gaining a source of support (28,30,38). Patients expressed the importance of being seen as a whole person, not just a patient (24,26,28,30,35), and valued being cared for by staff that they knew well (30,32,34). Developing personal relationships also promoted confidence in care, reducing anxiety when attending dialysis (28,34,35).

The Balance of Power within Relationships.

Some participants described an asymmetry of power between professionals and patients when decisions regarding care were made (24,26–28,30,39). Some described feeling like passive recipients of care because of a lack of dialogue with professionals, deficiencies in understanding, or a sense of powerlessness (24,27,28,30,40).

Seeking Expertise.

Health professionals were valued for their expertise and skills, both technical and interpersonal (30,32–36). Consequently, participants described anxiety when new or inexperienced staff were encountered (30,32,34). Ready access to the expertise of specific professionals, such as doctors, was also important (30,33).

Summation of These Themes

The first three analytic themes can be seen to describe a journey of change through patients’ initial realization of their new and altered self, encountering the challenges to lifestyle that dialysis presents followed by a potential acceptance and adaptation to regain a sense of control (41). This process of adjustment evolves over time in response to new health challenges and changes in life circumstances. Consequently, an individual’s transition along this pathway is likely to be subject to fluctuation over time. The fourth theme (relationships with health professionals) can be seen to influence (either positively or negatively) the other three themes and therefore, the potential for change. The influence of these relationships is, therefore, significant when we consider how health professionals can make meaningful changes to care or cause harm through a lack of attention to their influences on these other areas. These key themes, therefore, provide a new framework that can be used to focus strategies for improvement in care (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework of the experiences of adults living with in-center hemodialysis.

Discussion

Physician-led research has historically focused on biomedical measures of the dialysis process and prioritized blood test results or mortality as important outcomes. In contrast, the current framework has been developed from research exploring patients’ experiences of dialysis dependence; as such, it provides an opportunity to consider research and clinical outcomes that are likely to be of importance to patients. Although dialysis-requiring ESRD is recognized to be associated with increased mortality and changes in other clinical parameters, relatively less attention has been paid to the psychosocial effects of starting dialysis (42–44). The need for additional research into the psychosocial effects of CKD was also highlighted in a study of patients’ priorities for health research (9).

Maintenance of roles in society and family have been reported as critical for maintaining hope in patients with ESRD, and patients have deemed the provision of information on how to maintain these roles as a more important focus for care than its clinical effectiveness (45). Greater levels of social support have also been associated with improved quality of life, satisfaction with care, and rates of hospitalization (46).

The restrictions placed on patients as a result of their dialysis dependence have significant effects on their lives, and patients may be willing to accept a reduced life expectancy in exchange for fewer restrictions (8). Interventions that minimize the effect of these restrictions should, therefore, form an important part of care. Flexible scheduling of treatment and access to holiday dialysis may positively affect patients’ ability to live their lives around treatment (47). The symptoms that patients experience are also seen to restrict their lives. These symptoms may be under-recognized by health care professionals (48) and have been shown in other studies to be associated with reduced quality of life and increased mortality (49,50). Improved recognition of these symptoms may consequently lead to improved quality of life; however, there is limited evidence regarding effective strategies for managing such symptoms, and additional research is warranted (51).

This synthesis also highlights the importance that patients place on their relationships with health professionals. This requires professionals to be aware of the need for many patients to foster relationships that enable ongoing information provision, communication, and support. A perceived lack of information sharing has been linked with reduced satisfaction with care (7,52,53). In common with other studies, this synthesis highlights problems with information sharing between health professionals and patients with CKD (6,7,52,54).

Gaining knowledge is facilitated by effective communication with health professionals and was seen by some as fundamental to maintaining a sense of control. For several participants, developing self-care abilities also promoted a sense of control over their dialysis dependence. In other health care settings, obtaining a sense of control has been linked to improved outcomes, the adoption of self-care, and health-promoting activities (55–57). Although adequate information provision and promotion of self-care may be important to encourage control for some patients, additional research into other interventions that promote control in the hemodialysis population are needed.

The themes reported in this synthesis were well represented across the studies. There were no clear differences between included age ranges, geographic area, or time of publication. The results of this synthesis share similarities with two previous studies reporting the experiences of patients living with CKD and peritoneal dialysis (13,58). Both studies also emphasized the importance of acceptance and adaptation to gaining control (13,58). However, building relationships with health professionals did not seem to be of such importance in these studies. Patients living with predialysis CKD or other forms of RRT are likely to spend less time with and have reduced dependence on health professionals. The nature and influence of these relationships may consequently be different and confer more significance for those on in-center hemodialysis.

Most of the studies included in this synthesis did not report ethnicity, socioeconomic groups, or educational level. Additionally, we excluded studies that were not published in English. Because we excluded studies that included participants on other forms of RRT, the views of some in–center patients have been excluded from this review. In addition, because of the difficulties in searching for qualitative studies, the search strategy may not have identified all relevant studies; however, the themes identified were well represented across included studies, supporting the validity of the findings.

This synthesis of patients’ experiences of living with hemodialysis has resulted in a framework that can be used to consider interventions to improve patients’ experiences of care. The framework suggests that focusing on interventions that are incorporated into the established relationships that patients have with their health care professionals may enable patients’ to progress toward a sense of control and improve satisfaction with care.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Ian Watt for his advice and comments as a member of the Thesis Advisory Panel and Dr. David Moir for screening studies.

This work was completed as part of a postgraduate research degree.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Tuning into Qualitative Research—A Channel for the Patient Voice,” on pages 1128–1130.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.10561015/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, Neal B, Patrice HM, Okpechi I, Zhao MH, Lv J, Garg AX, Knight J, Rodgers A, Gallagher M, Kotwal S, Cass A, Perkovic V: Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Lancet 385: 1975–1982, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Renal Data System: 2014 USRDS Annual Data Report: An Overview of the Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabbay E, Meyer KB, Griffith JL, Richardson MM, Miskulin DC: Temporal trends in health-related quality of life among hemodialysis patients in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 261–267, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pruthi R, Steenkamp R, Feest T: UK Renal Registry 16th annual report: Chapter 8 survival and cause of death of UK adult patients on renal replacement therapy in 2012: National and centre-specific analyses. Nephron Clin Pract 125: 139–169, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin HR, Fink NE, Plantinga LC, Sadler JH, Kliger AS, Powe NR: Patient ratings of dialysis care with peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis. JAMA 291: 697–703, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Veer SN, Arah OA, Visserman E, Bart HA, de Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A, Heuveling LM, Stronks K, Jager KJ: Exploring the relationships between patient characteristics and their dialysis care experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 4188–4196, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer SC, de Berardis G, Craig JC, Tong A, Tonelli M, Pellegrini F, Ruospo M, Hegbrant J, Wollheim C, Celia E, Gelfman R, Ferrari JN, Törok M, Murgo M, Leal M, Bednarek-Skublewska A, Dulawa J, Strippoli GFM: Patient satisfaction with in-centre haemodialysis care: An international survey. BMJ Open 4: e005020, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, Rose J, Masterson R, Johnson DW, Howard K: Dialysis modality preference of patients with CKD and family caregivers: A discrete-choice study. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 102–111, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Carter SM, Hall B, Harris DC, Walker RG, Hawley CM, Chadban S, Craig JC: Patients’ priorities for health research: Focus group study of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3206–3214, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong A, Cheung KL, Nair SS, Kurella Tamura M, Craig JC, Winkelmayer WC: Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver perspectives on end-of-life care in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 913–927, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casey JR, Hanson CS, Winkelmayer WC, Craig JC, Palmer S, Strippoli GFM, Tong A: Patients’ perspectives on hemodialysis vascular access: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 937–953, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer SC, Hanson CS, Craig JC, Strippoli GF, Ruospo M, Campbell K, Johnson DW, Tong A: Dietary and fluid restrictions in CKD: A thematic synthesis of patient views from qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 559–573, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A, Lesmana B, Johnson DW, Wong G, Campbell D, Craig JC: The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 873–888, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J: Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 12: 181, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morton RL, Tong A, Webster AC, Snelling P, Howard K: Characteristics of dialysis important to patients and family caregivers: A mixed methods approach. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 4038–4046, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flemming K, Briggs M: Electronic searching to locate qualitative research: Evaluation of three strategies. J Adv Nurs 57: 95–100, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP): CASP Checklists, Oxford, 2014. Available at: www.casp-uk.net. Accessed March 29, 2015

- 18.Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, Smith JA: The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care 13: 223–225, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kane GA, Wood VA, Barlow J: Parenting programmes: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Child Care Health Dev 33: 784–793, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannes K: Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Research. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, 2011. Available at: http://cqrmg.cocrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance. Accessed March 29, 2015

- 21.Thomas J, Harden A: Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 8: 45, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxwell JA: A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research, Los Angeles, CA, SAGE, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J: Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 9: 59, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aasen EM, Kvangarsnes M, Heggen K: Perceptions of patient participation amongst elderly patients with end-stage renal disease in a dialysis unit. Scand J Caring Sci 26: 61–69, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Arabi S: Quality of life: Subjective descriptions of challenges to patients with end stage renal disease. Nephrol Nurs J 33: 285–292, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen D, Wainwright M, Hutchinson T: ‘Non-compliance’ as illness management: Hemodialysis patients’ descriptions of adversarial patient-clinician interactions. Soc Sci Med 73: 129–134, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson K, Cunningham J, Devitt J, Preece C, Cass A: “Looking back to my family”: Indigenous Australian patients’ experience of hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol 13: 114, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Axelsson L, Randers I, Jacobson SH, Klang B: Living with haemodialysis when nearing end of life. Scand J Caring Sci 26: 45–52, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calvey D, Mee L: The lived experience of the person dependent on haemodialysis. J Ren Care 37: 201–207, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregory DM, Way CY, Hutchinson TA, Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS: Patients’ perceptions of their experiences with ESRD and hemodialysis treatment. Qual Health Res 8: 764–783, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtin RB, Mapes D, Petillo M, Oberley E: Long-term dialysis survivors: A transformational experience. Qual Health Res 12: 609–624, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, Lützén K, Clyne N: The haemodialysis machine as a lifeline: Experiences of suffering from end-stage renal disease. J Adv Nurs 34: 196–202, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, Lützén K, Clyne N: Maintenance haemodialysis: Patients’ experiences of their life situation. J Clin Nurs 14: 294–300, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herlin C, Wann-Hansson C: The experience of being 30-45 years of age and depending on haemodialysis treatment: A phenomenological study. Scand J Caring Sci 24: 693–699, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaba E, Bellou P, Iordanou P, Andrea S, Kyritsi E, Gerogianni G, Zetta S, Swigart V: Problems experienced by haemodialysis patients in Greece. Br J Nurs 16: 868–872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karamanidou C, Weinman J, Horne R: A qualitative study of treatment burden among haemodialysis recipients. J Health Psychol 19: 556–569, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai AY, Loh AP, Mooppil N, Krishnan DS, Griva K: Starting on haemodialysis: A qualitative study to explore the experience and needs of incident patients. Psychol Health Med 17: 674–684, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell A, Farrand P, James H, Luke R, Purtell R, Wyatt K: Patients’ experience of transition onto haemodialysis: A qualitative study. J Ren Care 35: 99–107, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russ AJ, Shim JK, Kaufman SR: “Is there life on dialysis?”: Time and aging in a clinically sustained existence. Med Anthropol 24: 297–324, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih LC, Honey M: The impact of dialysis on rurally based Māori and their whānau/families. Nurs Prax N Z 27: 4–15, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bury M: Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn 4: 167–182, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noordzij M, Jager KJ: Increased mortality early after dialysis initiation: A universal phenomenon. Kidney Int 85: 12–14, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson BM, Zhang J, Morgenstern H, Bradbury BD, Ng LJ, McCullough KP, Gillespie BW, Hakim R, Rayner H, Fort J, Akizawa T, Tentori F, Pisoni RL: Worldwide, mortality risk is high soon after initiation of hemodialysis. Kidney Int 85: 158–165, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Broers NJH, Cuijpers ACM, van der Sande FM, Leunissen KML, Kooman JP: The first year on haemodialysis: A critical transition. Clin Kidney J 8: 271–277, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davison SN, Simpson C: Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: Qualitative interview study. BMJ 333: 886–889, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plantinga LC, Fink NE, Harrington-Levey R, Finkelstein FO, Hebah N, Powe NR, Jaar BG: Association of social support with outcomes in incident dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1480–1488, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appleby S: Shared care, home haemodialysis and the expert patient. J Ren Care 39[Suppl 1]: 16–21, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ: The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 82–99, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kimmel PL, Emont SL, Newmann JM, Danko H, Moss AH: ESRD patient quality of life: Symptoms, spiritual beliefs, psychosocial factors, and ethnicity. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 713–721, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pisoni RL, Wikström B, Elder SJ, Akizawa T, Asano Y, Keen ML, Saran R, Mendelssohn DC, Young EW, Port FK: Pruritus in haemodialysis patients: International results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 3495–3505, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hedayati SS: Improving symptoms of pain, erectile dysfunction, and depression in patients on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 5–7, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Veer SN, Jager KJ, Visserman E, Beekman RJ, Boeschoten EW, de Keizer NF, Heuveling L, Stronks K, Arah OA: Development and validation of the Consumer Quality index instrument to measure the experience and priority of chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3284–3291, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood R, Paoli CJ, Hays RD, Taylor-Stokes G, Piercy J, Gitlin M: Evaluation of the consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems in-center hemodialysis survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1099–1108, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krespi R, Bone M, Ahmad R, Worthington B, Salmon P: Haemodialysis patients’ beliefs about renal failure and its treatment. Patient Educ Couns 53: 189–196, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kidd L, Hubbard G, O’Carroll R, Kearney N: Perceived control and involvement in self care in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Nurs 18: 2292–2300, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skinner TC, Hampson SE: Personal models of diabetes in relation to self-care, well-being, and glycemic control. A prospective study in adolescence. Diabetes Care 24: 828–833, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziff MA, Conrad P, Lachman ME: The relative effects of perceived personal control and responsibility on health and health-related behaviors in young and middle-aged adults. Health Educ Q 22: 127–142, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Chadban S, Walker RG, Harris DC, Carter SM, Hall B, Hawley C, Craig JC: Patients’ experiences and perspectives of living with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 689–700, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.