Abstract

Background and objectives

Falls are common and associated with adverse outcomes in patients on dialysis. Limited data are available in earlier stages of CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We analyzed data from 8744 Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study participants ≥65 years old with Medicare fee for service coverage. Serious fall injuries were defined as a fall-related fracture, brain injury, or joint dislocation using Medicare claims. Hazard ratios (HRs) for serious fall injuries were calculated by eGFR and albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). Among 2590 participants with CKD (eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ACR≥30 mg/g), cumulative mortality after a serious fall injury compared with age-matched controls without a fall injury was calculated.

Results

Overall, 1103 (12.6%) participants had a serious fall injury over 9.9 years of follow-up. The incidence rates per 1000 person-years of serious fall injuries were 21.7 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 20.3 to 23.2), 26.6 (95% CI, 22.6 to 31.3), and 38.3 (95% CI, 31.2 to 47.0) at eGFR levels ≥60, 45–59, and <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively, and 21.3 (95% CI, 20.0 to 22.8), 31.7 (95% CI, 27.5 to 36.5), and 42.2 (95% CI, 31.3 to 56.9) at ACR levels <30, 30–299, and ≥300 mg/g, respectively. Multivariable adjusted HRs for serious fall injuries were 0.91 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.09) and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.86 to 1.37) for eGFR=45–59 and <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively, versus eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.11 to 1.54) and 1.81 (95% CI, 1.30 to 2.50) for ACR=30–299 and ≥300 mg/g, respectively, versus ACR<30 mg/g. Among participants with CKD, cumulative 1-year mortality rates among patients with a serious fall and age-matched controls were 21.0% and 5.5%, respectively.

Conclusions

Elevated ACR but not lower eGFR was associated with serious fall injuries. Evaluation for fall risk factors and fall prevention strategies should be considered for older adults with elevated ACR.

Keywords: CKD; falls; geriatric nephrology; Adult; albuminuria; Brain Injuries; Follow-Up Studies; Fractures, Bone; Humans; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic

Introduction

Falls are common among older adults and can result in serious injury and death (1–3). Although the risk for falls has been reported among older patients with ESRD (4,5), it is unclear whether an association exists between earlier stages of CKD and the risk for falls. Prior studies have shown only modest associations of reduced eGFR and elevated albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) with falls (6,7). However, these studies have been limited by a cross-sectional design, reliance on self-report to assess falls, and lack of information on falls that result in a serious injury. Although not all falls result in injury, older adults who experience a serious fall injury are at highest risk for functional decline, loss of independence, and nursing home placement (8,9). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the association of reduced eGFR and elevated ACR with risk for serious fall injuries defined as a fall-related fracture, brain injury, or joint dislocation. Additionally, among individuals with CKD, we evaluated risk factors for serious fall injuries and the association of a serious fall injury with mortality. To address these goals, we analyzed data from a prospective cohort study, the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study, linked to Medicare claims.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

The REGARDS Study was designed to evaluate the excess stroke mortality among black people compared with white people and residents of the southeastern United States. Details on the design and conduct of the REGARDS Study have been published previously (10). In brief, between January 1, 2003 and October 31, 2007, 30,239 participants were enrolled in the REGARDS Study. Black people and residents of the Stroke Belt region of the United States were oversampled. We restricted this analysis to REGARDS Study participants ≥65 year old (n=14,961) with Medicare Parts A and B but not C coverage at baseline (n=9528). Medicare is the United States federal health insurance program for people ≥65 years old and younger adults with disabilities or ESRD. Medicare Parts A and B are fee for service programs that provide insurance coverage for inpatient and outpatient care, respectively. Medicare Part C is a managed care program, and claims for individuals with this coverage are not complete. We excluded participants who did not have available data on eGFR (n=384) or ACR (n=355) and those on dialysis at baseline (n=45), leaving 8744 participants for this analysis. The REGARDS Study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the participating institutions, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection

Baseline data were obtained through a telephone interview, self-administered questionnaires, and an in–home study visit. Trained staff conducted computer–assisted telephone interviews to obtain information on demographics, education, household income, cigarette smoking status, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, impaired mobility, history of falls, and self-report of prior physician–diagnosed comorbid conditions and use of an antihypertensive medication. After the interview, an in–home study visit included the measurement of height, weight, and BP; a pill bottle review of all medications taken during the 2 weeks preceding the visit; collection of blood and urine samples, and an electrocardiogram (ECG). Blood samples were shipped overnight to the REGARDS Study central laboratory at the University of Vermont.

Atrial fibrillation was defined by self-report or ECG. History of coronary heart disease (CHD) was defined by self-report of a prior diagnosis, prior coronary revascularization procedure, or ECG evidence of myocardial infarction. Stroke was defined on the basis of self-report. Diabetes was defined by self-report of a prior diagnosis (excluding gestational diabetes) with current use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, a fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl, or a nonfasting blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl. After a standardized protocol, systolic BP and diastolic BP were measured two times with the participant in a seated position. The average of the two measurements was calculated. Hypotension was defined as systolic BP<110 mmHg. To be categorized as taking antihypertensive medication, participants had to both self-report taking antihypertensive medication and have one or more classes of antihypertensive medication identified during the pill bottle review. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized as <18.5, 18.5 to <25, and ≥25 kg/m2. Elevated C–reactive protein was defined as >3 mg/L. Cognitive impairment was defined as four or less on the six-item screener (11). The presence of depressive symptoms was defined as four or more on the four–item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (12). Exhaustion was defined as answering little or none to the Short Form 12 question, “How much of the time during the past 4 weeks did you have a lot of energy?” Impaired mobility was defined as responding a lot on the Short Form 12 question, “Does your health now limit you in climbing several flights of stairs?” Fall history was obtained by self-report within the past year. Psychoactive medication use was defined as using one or more of benzodiazepine, antipsychotics, or antidepressants, and polypharmacy was defined as the use of more than four medications.

Measures of Kidney Function

Serum creatinine assays were performed at the University of Vermont and calibrated with an isotope dilution mass spectroscopic standard. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation was used to calculate eGFR, which was categorized into three levels: ≥60, 45–59, and <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (13). Urinary albumin and urinary creatinine were measured at the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology at the University of Minnesota using the BN ProSpec Nephelometer from Dade Behring, Inc. (Newark, NJ) and reported as ACR (<30, 30–299, and ≥300 mg/g). CKD was defined as an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or an ACR≥30 mg/g.

Serious Fall Injuries and Mortality

We obtained data on serious fall injuries through Medicare claims. The REGARDS Study participants were linked to Medicare enrollment and claims data through December 31, 2012 by Social Security Number, with confirmation assessed by matching sex and date of birth obtained during the REGARDS Study interview with the Medicare beneficiary summary file. Using a previously published algorithm (14), we defined serious fall injuries as an emergency department or inpatient claim with a fall–related E code (8800–8889) and an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis code for nonpathologic skull, facial, cervical, clavicle, humeral, forearm, pelvic, hip, fibula, tibia, or ankle fractures (80000–80619, 8070–8072, 8080–8089, 81000–81419, 8180–8251, or 8270–8291); brain injury (85200–85239); or dislocation of the hip, knee, shoulder, or jaw (8300–83219, 83500–83513, or 83630–83660). For claims without a fall–related E code, emergency department or inpatient claims for the serious injuries listed above were defined as a serious fall injury in the absence of a motor vehicle accident E code (8100–8199) (14). For the analysis of serious fall injuries, participants were followed until their first serious fall injury, loss of Medicare fee for service Parts A or B coverage, initiation of Part C coverage, death, or December 31, 2012. Mortality was defined as date of death recorded in the Medicare beneficiary summary file. Medicare data are linked to the Social Security Administration to determine mortality information.

Statistical Analyses

Participant characteristics and the incidence rates of serious fall injuries were calculated by level of eGFR and separately, level of ACR. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) for serious fall injuries associated with levels of eGFR and separately, ACR. Initially, HRs were adjusted for age, race, sex, and geographic region of residence. In a second model, HRs were further adjusted for education, income, cigarette smoking, CHD, diabetes mellitus, stroke, atrial fibrillation, BMI, C-reactive protein, hypotension, and use of antihypertensive medication. A third model included additional adjustment for ACR when assessing the association of eGFR and serious fall injuries and eGFR when assessing ACR with serious fall injuries. Full multivariable adjustment (model 4) included variables in the third model and the following fall risk factors: cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, impaired mobility, self-reported falls in the year before baseline, use of a psychoactive medication, and polypharmacy. This analysis was repeated using a competing risk model to calculate sub-HRs for serious fall injuries accounting for deaths that occurred during follow-up (15). The joint effect of reduced eGFR and elevated ACR was assessed by calculating the HR for serious fall injuries by the cross categorization of eGFR and ACR levels. HRs for serious falls injuries associated with baseline characteristics (i.e., the covariates in model 4) were calculated among participants with CKD. Also, cumulative mortality was calculated among participants with CKD experiencing a serious fall injury and among age-matched controls with CKD but without a serious fall injury using the Kaplan–Meier method. Controls for this analysis were matched on age and being free of a serious fall injury at the time during follow-up when a participant experienced a serious fall injury using incidence density sampling.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, because older adults are more likely to have reduced muscle mass, which is associated with lower levels of urinary creatinine and may lead to higher ACR, we examined each component of ACR separately. Specifically, the HRs for serious fall injuries associated with urinary albumin, urinary creatinine, and ACR modeled as continuous variables (per twofold higher level) were calculated. Second, the associations of sex–specific urinary ACR (categorized as normal/mildly increased: ACR<17 mg/g in men, ACR<25 mg/g in women; moderately increased: ACR≥17–249 mg/g in men and ACR≥25–354 mg/g in women; or severely increased: ACR≥250 mg/g in men and ACR≥355 mg/g women) with serious fall injuries were calculated.

For all analyses, missing data for covariates (Supplemental Table 1) were imputed with 10 datasets using chained equations. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA/IC 13 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants with lower eGFR were more likely to be older; be women; have less than a high school education; report a lower household income; have atrial fibrillation, CHD, stroke, or diabetes mellitus; and use an antihypertensive medication (Table 1). At lower levels of eGFR, a higher percentage of participants had fall risk factors, including cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, impaired mobility, and a self-reported fall in the prior year. Similar patterns of demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and fall risk factors were seen at higher levels of ACR, with the exceptions that a lower percentage of those with higher ACR were women and a higher percentage of those with higher ACR were black (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study Medicare–linked population ≥65 years old by eGFR

| Participant Characteristics | eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | P Value Trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥60, n=7140 | 45–59, n=1064 | <45, n=540 | ||

| Age, yr | ||||

| <70 | 39.5 | 21.8 | 19.8 | <0.001 |

| 70–79 | 48.9 | 54.0 | 47.0 | 0.38 |

| ≥80 | 11.6 | 24.3 | 33.2 | <0.001 |

| Women | 49.2 | 52.2 | 55.7 | 0.001 |

| Black | 31.1 | 31.2 | 36.1 | 0.04 |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Stroke Belt | 36.4 | 35.9 | 33.0 | 0.14 |

| Stroke Buckle | 22.8 | 22.0 | 25.4 | 0.42 |

| Other region | 40.8 | 42.1 | 41.7 | 0.46 |

| Less than a high school education | 14.3 | 18.5 | 20.7 | <0.001 |

| Household income <$20,000 | 21.8 | 24.1 | 32.5 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 9.4 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10.1 | 13.9 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 22.9 | 32.1 | 39.2 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 7.0 | 11.5 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20.2 | 27.1 | 36.6 | <0.001 |

| Hypotension (systolic BP <110 mmHg) | 8.1 | 7.4 | 8.5 | 0.94 |

| Use of antihypertensive medication | 52.4 | 72.9 | 79.6 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.10 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 27.9 | 26.1 | 23.7 | 0.02 |

| ≥25.0 | 70.7 | 71.6 | 74.4 | 0.07 |

| High–sensitivity C–reactive protein >3 mg/L | 2.8 | 5.0 | 6.1 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 9.2 | 13.3 | 15.8 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.4 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 0.08 |

| Exhaustion | 11.8 | 17.2 | 21.9 | <0.001 |

| Impaired mobility | 15.1 | 21.2 | 28.0 | <0.001 |

| Self-reported fall in the prior year | 7.6 | 9.7 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Use of psychoactive medication | 14.6 | 20.1 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Polypharmacy (more than four medications) | 63.0 | 76.8 | 87.4 | <0.001 |

Numbers are percentages. The Stroke Buckle includes the coastal plain of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The Stroke Belt includes the remainder of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia and the states of Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas. Other region includes the 40 other contiguous states in the United States and Washington, DC.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study Medicare–linked population ≥65 years old by albumin-to-creatinine ratio

| Participant Characteristics | Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio, mg/g | P Value Trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30, n=7221 | 30–299, n=1271 | ≥300, n=252 | ||

| Age, yr | ||||

| <70 | 37.7 | 28.3 | 31.8 | <0.001 |

| 70–79 | 49.1 | 51.4 | 48.8 | 0.31 |

| ≥80 | 13.3 | 20.3 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| Women | 51.1 | 45.5 | 38.1 | <0.001 |

| Black | 30.0 | 35.3 | 52.8 | <0.001 |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Stroke Belt | 36.4 | 35.7 | 29.4 | 0.06 |

| Stroke Buckle | 22.9 | 22.0 | 26.2 | 0.79 |

| Other region | 40.7 | 42.3 | 44.4 | 0.11 |

| Less than a high school education | 14.2 | 19.3 | 21.0 | <0.001 |

| Household income <$20,000 | 21.5 | 27.9 | 32.9 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 8.5 | 13.1 | 15.1 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 23.0 | 32.0 | 47.5 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 6.9 | 12.1 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18.5 | 36.0 | 54.4 | <0.001 |

| Hypotension (systolic BP <110 mmHg) | 8.7 | 5.0 | 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Use of antihypertensive medication | 54.3 | 65.2 | 81.0 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.06 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 27.8 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 0.07 |

| ≥25.0 | 70.8 | 71.9 | 73.8 | 0.21 |

| High–sensitivity C–reactive protein >3 mg/L | 2.6 | 5.9 | 9.9 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 9.5 | 12.1 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.3 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 0.002 |

| Exhaustion | 11.8 | 18.7 | 20.2 | <0.001 |

| Impaired mobility | 15.1 | 24.0 | 22.2 | <0.001 |

| Self-reported fall in the prior year | 7.4 | 10.9 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Use of psychoactive medication | 15.5 | 16.8 | 15.9 | 0.30 |

| Polypharmacy (more than four medications) | 64.4 | 73.0 | 81.4 | <0.001 |

Numbers are percentages. The Stroke Buckle includes the coastal plain of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The Stroke Belt includes the remainder of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia and the states of Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas. Other region includes the 40 other contiguous United States states and Washington, DC.

CKD and Serious Fall Injuries

Overall, 1103 (12.6%) participants had a serious fall injury over 47,745 person-years of follow-up (median follow-up of 5.9 years and maximum follow-up of 9.9 years). The incidence rates per 1000 person-years (95% confidence interval [95% CI]) of serious fall injuries were 21.7 (95% CI, 20.3 to 23.2), 26.6 (95% CI, 22.6 to 31.3), and 38.3 (95% CI, 31.2 to 47.0) at eGFR levels ≥60, 45–59, and <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively, and 21.3 (20.0 to 22.8), 31.7 (95% CI, 27.5 to 36.5), and 42.2 (95% CI, 31.3 to 56.9) at ACR levels <30, 30–299, and ≥300 mg/g, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence rates and hazard ratios for serious fall injuries associated with eGFR and separately, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio

| eGFR and ACR Levels | Incidencea (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | |||||

| ≥60 | 21.7 (20.3 to 23.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 45–59 | 26.6 (22.6 to 31.3) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.23) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.17) | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.13) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) |

| <45 | 38.3 (31.2 to 47.0) | 1.38 (1.10 to 1.72) | 1.23 (0.99 to 1.55) | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.40) | 1.09 (0.86 to 1.37) |

| ACR, mg/g | |||||

| <30 | 21.3 (20.0 to 22.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 30–299 | 31.7 (27.5 to 36.5) | 1.48 (1.26 to 1.73) | 1.33 (1.13 to 1.56) | 1.33 (1.13 to 1.55) | 1.31 (1.11 to 1.54) |

| ≥300 | 42.2 (31.3 to 56.9) | 2.32 (1.70 to 3.15) | 1.90 (1.39 to 2.62) | 1.86 (1.34 to 2.57) | 1.81 (1.30 to 2.50) |

Model 1 is adjusted for age, race, sex, and geographic region of residence. Model 2 is adjusted for variables in model 1 and education, income, smoking status, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, stroke, atrial fibrillation, body mass index, C-reactive protein >3 mg/L, hypotension, and use of antihypertensive medication. Model 3 is adjusted for variables in model 2 and albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) for the model of eGFR and eGFR for the model of ACR. Model 4 is adjusted for variables in model 3 and cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, exhaustion, impaired mobility, self-reported falls in the year before baseline, use of psychoactive medication, and polypharmacy. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Incidence per 1000 person-years.

No association was present between eGFR and serious fall injuries after multivariable adjustment (Table 3). There was a graded association between level of ACR and serious fall injuries before and after multivariable adjustment. After full multivariable adjustment and compared with those with an ACR<30 mg/g, the HRs (95% CIs) for serious fall injuries were 1.31 (95% CI, 1.11 to 1.54) and 1.81 (95% CI, 1.30 to 2.50) for participants with ACR=30–299 and ≥300 mg/g, respectively. Similar to the Cox proportional hazards models, no association was present between lower eGFR and serious fall injuries in the competing risk model (Supplemental Table 2). In the competing risk analysis, ACR remained associated with higher risk for serious fall injuries. The joint association of reduced eGFR and elevated ACR is displayed in Supplemental Table 3.

Risk Factors for Serious Fall Injuries in Participants with CKD

Among participants with CKD (n=2590), 386 (14.9%) had a serious fall injury during follow-up over 12,756 person-years (median follow-up of 5.2 years and maximum follow-up of 9.9 years). In the multivariable adjusted model, age ≥80 years old, women, CHD, diabetes mellitus, BMI<18.5 kg/m2, depressive symptoms, and self-report of a fall in the prior year were associated with a higher risk of a serious fall injury. Black race and BMI≥25.0 kg/m2 were associated with a lower risk for a serious fall injury (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios for serious fall injuries among participants with CKD (n=2590)

| Participant Characteristics | Multivariable Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | |

| <70 | 1 (reference) |

| 70–79 | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.53) |

| ≥80 | 1.77 (1.31 to 2.40) |

| Women | 1.42 (1.13 to 1.78) |

| Black | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.73) |

| Geographic region | |

| Stroke Belt | 0.92 (0.73 to 1.17) |

| Stroke Buckle | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.43) |

| Other region | 1 (reference) |

| Less than a high school education | 1.13 (0.85 to 1.51) |

| Household income <$20,000 | 1.09 (0.83 to 1.42) |

| Current smoker | 0.93 (0.64 to 1.35) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.24 (1.00 to 1.55) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.66 (1.33 to 2.09) |

| Stroke | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.70) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.16 (0.89 to 1.52) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |

| <18.5 | 2.00 (1.16 to 3.46) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1 (reference) |

| ≥25.0 | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.96) |

| High–sensitivity C–reactive protein >3 mg/L | 1.47 (0.94 to 2.30) |

| Hypotension (systolic BP <110 mmHg) | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.05) |

| Use of antihypertensive medication | 0.89 (0.70 to 1.12) |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.21 (0.85 to 1.71) |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.53 (1.15 to 2.05) |

| Exhaustion | 1.10 (0.84 to 1.44) |

| Impaired mobility | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.13) |

| Self-reported fall in the prior year | 1.78 (1.34 to 2.37) |

| Use of psychoactive medication | 1.15 (0.89 to 1.49) |

| Polypharmacy (more than four medications) | 1.25 (0.94 to 1.66) |

Serious Fall Injuries and Mortality in Participants with CKD

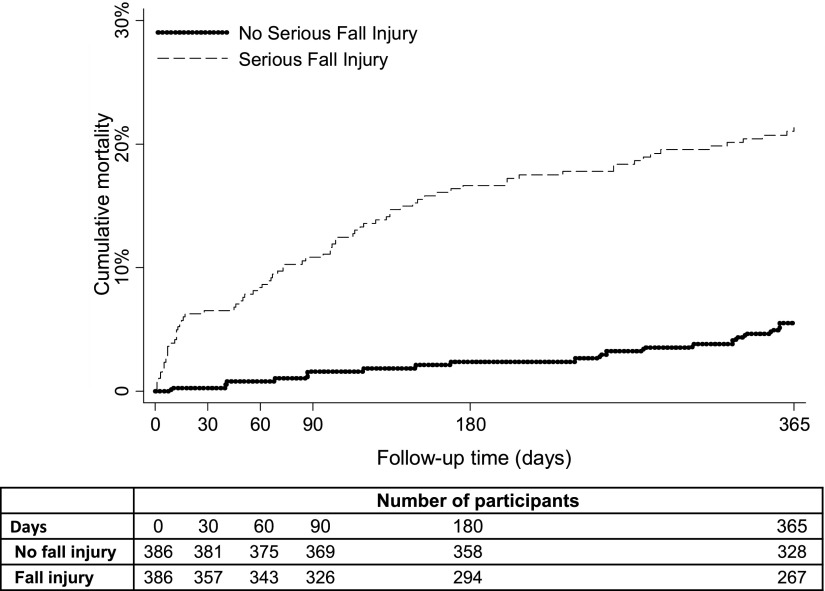

Among participants with CKD, 993 (38.3%) died over 12,756 person-years of follow-up. Participants with CKD who had serious fall injuries experienced higher mortality over the following year compared with their counterparts who did not have a serious fall injury (Figure 1). Cumulative mortality rates among those with a serious fall injury and age-matched controls without a serious fall injury were 6.5% and 0.3%, respectively, at 30 days and 21.0% and 5.5%, respectively, at 365 days.

Figure 1.

Among those with CKD, compared with age-matched controls without a serious fall injury, having a serious fall injury was associated with higher mortality over the following year. Cumulative mortality rates among patients with a serious fall injury and age-matched controls without a serious fall injury were 6.5% and 0.3%, respectively, at 30 days and 21.0% and 5.5%, respectively, at 365 days.

Sensitivity Analyses

Compared with urinary albumin and separately, urinary creatinine, a stronger association was present between ACR and serious fall injuries (Supplemental Table 4). Consistent with the main analysis, higher sex–specific urinary ACR categories were associated with higher risks for serious fall injuries (Supplemental Table 5).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of older adults with Medicare fee for service coverage, there were higher rates of serious fall injuries at lower levels of eGFR and higher levels of ACR. After multivariable adjustment for demographic factors, comorbid conditions, and fall risk factors, higher ACR levels but not lower eGFR levels were associated with serious fall injuries. Although attenuated, the association between higher ACR and serious fall injuries remained present when accounting for the competing risk of death. Among participants with CKD, independent risk factors for serious fall injuries included age ≥80 years old, women, CHD, diabetes mellitus, BMI<18.5 kg/m2, depressive symptoms, and a self-reported history of falls. Furthermore, among participants with CKD who experienced a serious fall injury, nearly one in five died within a year of the fall.

Prior studies have shown that falls are common and associated with poor health outcomes among older patients on hemodialysis and older patients on peritoneal dialysis (4,5). For example, in one prospective study, investigators found an adjusted rate of 1.7 falls per year among patients on peritoneal dialysis. Falls were associated with subsequent mortality in this study (5). However, prior studies were not able to distinguish fall risk related to the dialysis treatment itself versus underlying kidney disease. The association between earlier stages of kidney disease and falls has been less well studied. Prior studies have shown modest associations between measures of kidney function and a self-reported history of recurrent falls (7,16–18).

There are several potential explanations for the associations that we report. Although there were higher rates of serious fall injuries at lower levels of eGFR, these associations were not present after multivariable adjustment, suggesting confounding because of the presence of comorbidities, such as diabetes and stroke. In contrast, an association between elevated ACR and fall injuries was present after multivariable adjustment. Among older adults, elevated ACR has been shown to be associated with established fall risk factors, including cognitive impairment and mobility impairment (6,19). Shared risk factors for these geriatric conditions and albuminuria, such as vascular endothelial damage, may explain the associations between ACR and serious fall injuries (20). It is also possible that microvascular disease directly impairs muscle metabolism or affects physical performance, leading to a higher risk for falls (21,22). Inflammation may also play a role in loss of muscle mass in CKD through the insulin resistance and stimulation of muscle proteolysis (23).

Findings from this analysis have important clinical implications. Although the majority of adults with reduced eGFR or elevated ACR will not progress to ESRD (24,25), a serious fall injury may lead to loss of independence, nursing home placement, and death. Multicomponent and risk factor–targeted fall prevention interventions that address both predisposing and precipitating risk factors have been shown to reduce fall rates (2,26–28). This study suggests that reduced eGFR may be a marker of higher fall risk and that elevated ACR may be an independent predisposing factor associated with serious fall injuries. Additionally, we identified several factors associated with higher risk of a serious fall injury among older adults with CKD. For example, a self-reported fall in the prior year was associated with a future serious fall injury. Adding routine fall risk assessment to the management of older adults with CKD may prevent fall-related injuries, an outcome that is important to patients. Additionally, elevated ACR may be a useful risk factor to identify older adults at higher risk for serious fall injuries. Future studies are necessary to determine if routine measurement of ACR in the general clinic population is practical or cost efficient for identifying older adults at risk for serious fall injuries and reducing these injuries. Because older adults are at risk for multiple falls, future studies may also consider the association of ACR with recurrent fall injuries using multistate illness-death models (29).

These findings should be interpreted in the context of known and potential limitations. This analysis was restricted to community–dwelling older adults with Medicare fee for service Parts A and B coverage, and findings may not be generalizable to younger adults or those residing in nursing homes. Although falls were ascertained through Medicare claims using a previously published algorithm, misclassification remains possible. Information on concurrent CKD complications, such as serum bicarbonate, was not available, and we could not assess the effect of acidosis on the association between measures of kidney function and serious fall injuries. Objective measures of physical performance, such as gait speed, balance, or lower extremity strength, or the use of assistive devices, such as walkers or canes, were not assessed during the baseline REGARDS Study visit. Because eGFR and ACR were only obtained at baseline, we could not determine the association of serious fall injuries and mortality adjusting for level of kidney function. Lastly, data on other known risk factors for falls, including visual or hearing impairment, low standing BP, or environmental hazards such as loose rugs or lack of stair rails, were not available.

In conclusion, among older adults, the incidence of serious fall injuries was higher at lower levels of eGFR and higher levels of ACR. However, only ACR was associated with risk for serious fall injuries after adjustment for potential confounders. A serious fall injury was associated with substantially higher mortality. Evaluation for fall risk factors and multicomponent fall prevention strategies should be considered for older adults with CKD to reduce fall-related injuries.

Disclosures

K.R., N.C.W., and P.M. received research support from Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA). O.M.G. and D.G.W. have received past research support from Amgen, Inc. None of the other authors declare any conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study for their valuable contributions.

This research project is supported by cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service. Additional support was provided through National Institute on Aging grant R03AG042336, the T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award (funding provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc., the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Association of Specialty Professors, the American Society of Nephrology, and the American Geriatrics Society), and Department of Veterans Affairs grant 1IK2CX000856 (to C.B.B.). This work was also supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant K24-HL125704 (to D.S.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. Representatives of the funding agency have been involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

A full list of participating REGARDS Study investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11111015/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tinetti ME, Williams CS: Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 337: 1279–1284, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Kumar C: The patient who falls: “It’s always a trade-off”. JAMA 303: 258–266, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF: Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 319: 1701–1707, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook WL, Tomlinson G, Donaldson M, Markowitz SN, Naglie G, Sobolev B, Jassal SV: Falls and fall-related injuries in older dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1197–1204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farragher J, Chiu E, Ulutas O, Tomlinson G, Cook WL, Jassal SV: Accidental falls and risk of mortality among older adults on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1248–1253, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowling CB, Booth JN 3rd, Gutiérrez OM, Kurella Tamura M, Huang L, Kilgore M, Judd S, Warnock DG, McClellan WM, Allman RM, Muntner P: Nondisease-specific problems and all-cause mortality among older adults with CKD: The REGARDS Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1737–1745, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roderick PJ, Atkins RJ, Smeeth L, Nitsch DM, Hubbard RB, Fletcher AE, Bulpitt CJ: Detecting chronic kidney disease in older people; what are the implications? Age Ageing 37: 179–186, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG: The course of disability before and after a serious fall injury. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1780–1786, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG: Association of injurious falls with disability outcomes and nursing home admissions in community-living older persons. Am J Epidemiol 178: 418–425, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: Objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 25: 135–143, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC: Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care 40: 771–781, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radloff L: The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1: 385–401, 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, McAvay GJ, Peduzzi P, Gross CP, Zhou B, Lin H: Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med 174: 588–595, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dukas LC, Schacht E, Mazor Z, Stähelin HB: A new significant and independent risk factor for falls in elderly men and women: A low creatinine clearance of less than 65 ml/min. Osteoporos Int 16: 332–338, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher JC, Rapuri P, Smith L: Falls are associated with decreased renal function and insufficient calcitriol production by the kidney. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 103: 610–613, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall RK, Landerman LR, O’Hare AM, Anderson RA, Colón-Emeric CS: Chronic kidney disease and recurrent falls in nursing home residents: A retrospective cohort study. Geriatr Nurs 36: 136–141, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurella Tamura M, Muntner P, Wadley V, Cushman M, Zakai NA, Bradbury BD, Kissela B, Unverzagt F, Howard G, Warnock D, McClellan W: Albuminuria, kidney function, and the incidence of cognitive impairment among adults in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 756–763, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurella Tamura M, Xie D, Yaffe K, Cohen DL, Teal V, Kasner SE, Messé SR, Sehgal AR, Kusek J, DeSalvo KB, Cornish-Zirker D, Cohan J, Seliger SL, Chertow GM, Go AS: Vascular risk factors and cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 248–256, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo HK, Al Snih S, Kuo YF, Raji MA: Chronic inflammation, albuminuria, and functional disability in older adults with cardiovascular disease: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2008. Atherosclerosis 222: 502–508, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheuermann-Freestone M, Madsen PL, Manners D, Blamire AM, Buckingham RE, Styles P, Radda GK, Neubauer S, Clarke K: Abnormal cardiac and skeletal muscle energy metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation 107: 3040–3046, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang XH, Mitch WE: Muscle wasting from kidney failure-a model for catabolic conditions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 2230–2238, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, Bacchetti P, Garg AX, Kaufman JS, Walter LC, Mehta KM, Steinman MA, Allon M, McClellan WM, Landefeld CS: Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2758–2765, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hare AM, Hotchkiss JR, Kurella Tamura M, Larson EB, Hemmelgarn BR, Batten A, Do TP, Covinsky KE: Interpreting treatment effects from clinical trials in the context of real-world risk information: End-stage renal disease prevention in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 174: 391–397, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heung M, Adamowski T, Segal JH, Malani PN: A successful approach to fall prevention in an outpatient hemodialysis center. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1775–1779, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinetti ME: Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med 348: 42–49, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, Koch ML, Trainor K, Horwitz RI: A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med 331: 821–827, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warnock DG: Competing risks: You only die once [published online ahead of print January 31, 2016]. Nephrol Dial Transplant [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.