Abstract

Preeclampsia is a common disorder in pregnancy and may affect multiple maternal and foetal organ systems. Less common disorders with similar features may imitate preeclampsia though require different management strategies and with different prognostic implications for mother and baby. We present a case of a pregnant woman who developed severe hypertension and proteinuria in pregnancy. The early onset of these changes prompted investigation for causes other than preeclampsia, leading to a diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome due to stage III adrenocortical cancer. The changes in management strategy, the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to care, and the prognostic implications for the mother are discussed.

Keywords: High-risk pregnancy, endocrinology, cancer

Case

A 27-year-old gravida 2 para 1 at 26 weeks gestation was transferred from another hospital with a diagnosis of severe early onset preeclampsia. There was no significant past medical history, and the subjects’ previous pregnancy was uneventful. The mother’s booking blood pressure had been elevated at 135/88 mmHg at 13 weeks gestation, and she was commenced on antihypertensive drug therapy at 19 weeks gestation when her blood pressure was 160/105 mmHg. Despite escalating doses of labetalol and methyldopa, her blood pressure remained elevated, and she developed proteinuria quantified at 2 g in 24 h.

On transfer, the mothers’ body mass index was 34.6 g/m2, blood pressure was 180/105 mmHg, there was ++++ proteinuria on dipstick testing and pitting oedema to the knees. Her serum potassium was 3.4 mmol/L and her blood sugar monitoring was unremarkable. Slow release nifedipine was added to maximal doses of labetalol and methyldopa.

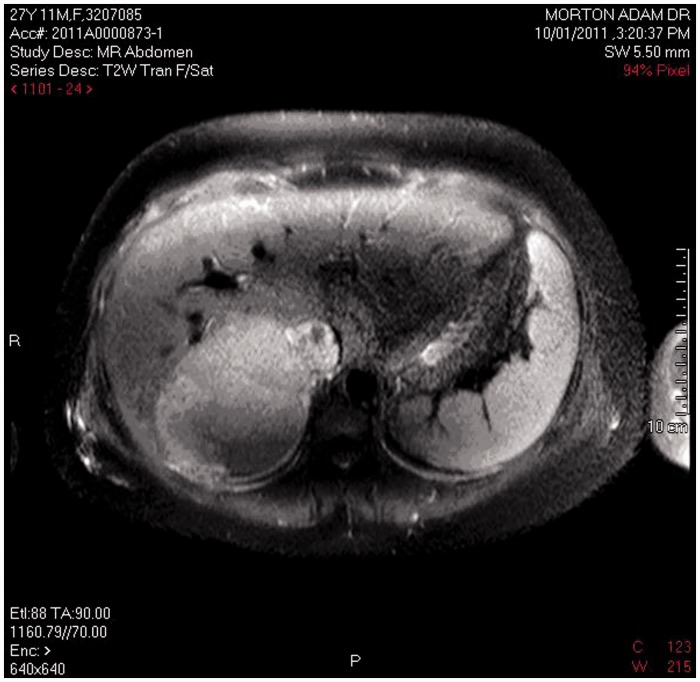

A procoagulant screen was normal, and urinary and plasma metanephrines and aldosterone:renin ratio were normal (aldosterone was 226 pmol/L and plasma renin activity was 28 mU/L), with an inactive urinary sediment. Twenty-four-hour urine-free cortisol was elevated at 1150 nmol/day using a local ultra high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry assay1 (normal < 150), midnight serum cortisol was 923 nmol/L and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was suppressed consistent with a diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome (CS) due to primary adrenal disease. The mother had impressive cutaneous striae, but no bruising, skin atrophy, proximal myopathy or other Cushingoid features. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a 12 cm by 8 cm homogenous right adrenal mass with invasion of the inferior vena cava (IVC) consistent with adrenocortical cancer (Figure 1). The left adrenal gland was atrophic. Serum androstenedione was elevated at 120 nmol/L (normal < 12), dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEA-S) was 11 µmol/L (normal 1–11); no result for serum testosterone was obtained. There was no evidence of metastatic disease on computer axial tomography of the chest, and left ventricular function was normal on echocardiography. Ultrasound of the foetus revealed normal growth and placental Dopplers with an estimated foetal weight of 1039 g. The mother’s blood pressure remained uncontrolled with systolic readings ranging between 160 and 190 mmHg and diastolic between 90 and 120 mmHg despite maximal doses of methyldopa, labetalol, nifedipine, and clonidine. Metyrapone was not used because of the risk of exacerbating maternal blood pressure. Spironolactone was not used because of relatively slow onset as an antihypertensive and the acute nature of hypertension encountered. A multidisciplinary meeting involving health professionals in obstetrics, midwifery, neonatology, anaesthetics, endocrine and vascular surgery, endocrinology, and obstetric medicine was held to discuss management options.

Figure 1.

MRI of right adrenal tumour.

Surgical removal of the malignancy with the foetus in utero would involve prolonged clamping of the maternal IVC with uncertain risk for the foetus. Removal of the right adrenal with the baby in utero deferring exploration of the IVC until the postpartum period would not be in the mother’s best interests from a surgical point of view. Venous bypass to enable exploration of the IVC with the foetus in utero was considered but felt to be experimental with uncertain risk to the foetus.

The management options were discussed with the mother and father. They elected to proceed to caesarean section at 27 weeks gestation. A healthy live female birth weight 990 g was delivered. There was no virilisation of the neonate. Five days postpartum, the mother underwent surgery for removal of the right adrenal mass and exploration of the IVC. An 808 g well-circumscribed encapsulated tumour was removed, histology confirming adrenal cortical carcinoma with six of nine of the modified Weiss criteria. Immunostains were strongly positive for inhibin, but negative for luteinising hormone (LH), beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), and chromogranin. Tissue removed from the IVC revealed organised thrombus with two foci of adrenal cortical tumour 0.5 mm and 0.7 mm in diameter.

Postpartum, the mother was commenced on mitotane and prednisone. Her antihypertensives were weaned and ceased within three weeks of removal of the tumour. There was no evidence of recurrence hormonally or radiologically three months postpartum, but imaging five months postpartum revealed multiple pulmonary metastases and a soft tissue recurrence in the right adrenal bed between the IVC and the liver. The mother proceeded to six cycles of etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. She is now 14 months postpartum with stable metastatic disease radiologically.

Literature review

CS is rare in pregnancy, with fewer than 180 cases reported in the literature. It is a severe disease with a high rate of maternal and foetal morbidity including maternal hypertension in 68%, maternal diabetes mellitus in 25%, intrauterine growth retardation in 25%, premature birth in 43%, and stillbirth in 6% of pregnancies.2 Maternal death has been reported in 2% of pregnancies. Importantly, CS may present with severe refractory hypertension and proteinuria mimicking preeclampsia.

The aetiology of CS in pregnancies reported to date include 49 cases of pituitary Cushing’s disease (CD), 68 cases of adrenal adenoma, 21 cases of adrenal carcinoma, seven cases of ectopic ACTH syndrome, and 15 cases of pregnancy-induced CS due to aberrant LH/hCG receptor expression. This is markedly different from the aetiology of CS in the non-pregnant population, where approximately 70% of cases are due to pituitary ACTH-dependent disease, and only 20% due to ACTH-independent adrenal adenomas and carcinomas.

Diagnosis of CS is complicated by changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in pregnancy. These changes include a three-fold rise in cortisol-binding globulin, a three-fold rise in urine free cortisol, and a 1.6-fold rise in serum free cortisol. The placenta also produces ACTH (with levels rising three-fold from first to third trimester) and corticotrophin releasing hormone. In addition, progesterone has anti-glucocorticoid effects. Both serum renin and aldosterone also increase in normal pregnancy, with approximately four- and eight-fold increases, respectively. Plasma renin activity consequently increases approximately seven-fold and rises in this correlate to increasing serum aldosterone.3

A 24-h urine-free cortisol greater than three times the upper end of the normal non-pregnant range is strongly suggestive of CS in pregnancy. The circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion is usually preserved in pregnancy, though lost in CS, and may be useful in diagnosis. ACTH levels cannot be used to differentiate between pituitary and adrenal disease, as only 50% of patients with adrenal disease have a suppressed ACTH, and a few patients with CD have been reported with suppressed ACTH levels.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the adrenals and pituitary without contrast are safe in pregnancy. Inferior petrosal sinus sampling has only rarely been performed because of concerns regarding radiation exposure to the foetus.

The treatment of choice of CS due to pituitary or adrenal disease in pregnancy is surgery in second trimester. If surgery cannot be performed because of gestation or failure to localise the cause, metyrapone may be used as medical therapy, albeit with the risk of worsening hypertension. Long-acting somatostatin analogues have been used throughout three pregnancies to control CS due to bronchial carcinoid producing ectopic ACTH.4

Adrenocortical carcinomas (ACC) are rare tumours with an incidence estimated at 0.5–2 per million per year in adults.5 They are associated with a poor prognosis with an estimated five-year survival of less than 30%. Fewer than 20 cases have been described in pregnancy. The largest review series of 12 women (three diagnosed during pregnancy and nine diagnosed within six months of delivery) revealed that all 12 tumours secreted cortisol and nine tumours co-secreted androgens.6 Pregnancy was uncomplicated in only four of the 12 pregnancies. Premature birth occurred in five pregnancies, intrauterine growth retardation in three pregnancies, one pregnancy was terminated because of severe preeclampsia with haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) at 12 weeks gestation, and there was one intrauterine foetal death. Four mothers developed hypertension and three developed diabetes mellitus. All of the women except one had surgical removal of carcinoma, and 10 of the women received mitotane. Survival rate was only 50% at one year, 28% at three years, 13% at five years, and 0% at eight years. Diagnosis of ACC during pregnancy or in the early postpartum period has a much poorer prognosis than diagnosis in non-pregnant women with a hazard ratio for death of 3.98. This may be due to pregnancy-related tumours secreting cortisol, a feature associated with particularly poor outcome in a larger series of non-pregnant individuals diagnosed with ACC.5 Other case reports of pregnancies complicated by CS due to ACC describe oligohydramnios and intrauterine foetal death at 25 weeks gestation, and virilisation of a female infant.7,8

Extension of ACC into the IVC is associated with poor prognosis. A series of 15 non-pregnant individuals treated surgically for ACC with extension into the IVC reported two post-operative deaths, and 10 patients dying of metastatic complications at 4–31 months with a median survival time of eight months.9

In conclusion, CS is a rare disease complicating pregnancy associated with significant maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. It may mimic early onset preeclampsia in presenting with refractory hypertension and proteinuria. The maternal prognosis is particularly poor in mothers with CS due to ACC.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Written consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Guarantor

Adam Morton

Contributorship

Elizabeth Jarvis and Adam Morton cared for the subject, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.McWhinney BC, Briscoe SE, Ungerer JPJ, et al. Measurement of cortisol, cortisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone and 11-deoxycortisol with ultra high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: Application for plasma, plasma ultrafiltrate, urine and saliva in a routine laboratory. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2010; 878: 2863–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsay JR, Jonklaas J, Oldfield EH, et al. Cushing’s syndrome during pregnancy: personal experience and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 3077–3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson M, Morganti AA, Zervoudakis I, et al. Blood pressure, the renin-aldosterone system and sex steroids throughout normal pregnancy. Am J Med 1980; 68: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naccache DD, Zaina A, Shen-Or Z, et al. Uneventful octreotide LAR therapy throughout three pregnancies, with favorable delivery and anthropometric measures for each newborn: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2011; 5: 386–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abiven G, Coste J, Groussin L, et al. Clinical and biological features in the prognosis of adrenocortical cancer: poor outcome of cortisol-secreting tumors in a series of 202 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91: 2650–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abiven-Lepage G, Coste J, Tissier F, et al. Adrenocortical carcinoma and pregnancy: clinical and biological features and prognosis. Eur J Endocrinol 2010; 163: 793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Groot PC, Van Kamp IL, Zweers EJ, et al. Oligohydramnios in a pregnant woman with Cushing’s syndrome caused by an adrenocortical adenoma. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2007; 20: 431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris LF, Park S, Daskivich T, et al. Virilization of a female infant by a maternal adrenocortical carcinoma. Endocr Pract 2011; 17: e26–e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiche L, Dousset B, Kieffer E, et al. Adrenocortical carcinoma extending into the inferior vena cava: presentation of a 15-patient series and review of the literature. Surgery 2006; 139: 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]