Abstract

Globally, the nature of maternal mortality and morbidity is shifting from direct obstetric causes to an increasing proportion of indirect causes due to chronic conditions and ageing of the maternal population. Obstetric medicine can address an important gap in the care of women by broadening its scope to include colleagues, communities and countries that do not yet have established obstetric medicine training, education and resources. We present the concept of global obstetric medicine by highlighting three low- and middle-income country experiences as well as an example of successful collaboration. The article also discusses ideas and initiatives to build future partnerships within the global obstetric medicine community.

Keywords: Global health, maternal mortality, maternal morbidity, non-communicable diseases

Introduction

Last year, International Society of Obstetric Medicine (ISOM) president Sandra Lowe wrote that “the challenge now [for the discipline of obstetric medicine] is to reach out to clinicians caring for women with medical disorders of pregnancy who do not have access to obstetric physicians and have not had this specialised training”.1 These comments are timely, as we countdown to the end of the millennium development goals (MDGs), critical measures of a country’s development and health progress. With only nine countries on track to achieve the MDG 5 target of a 75% reduction in maternal mortality,2 the post-MDG 2015 maternal health agenda is a full one. Work must address changing health trends, termed ‘obstetric transition’ – a shift from patterns of high maternal mortality that reflects the natural history of pregnancy and death predominantly due to direct obstetric causes, to patterns of lower maternal mortality that increasingly, are related to older maternal age, non-communicable disease (NCD) and indirect causes of maternal death.3 In addition to promoting social equity, health systems strengthening and a focus on quality of care are critical to making the transition to later stages of ‘obstetric transition’ (Table 1), and obstetric medicine as a discipline can make an important contribution.

Table 1.

The ‘obstetric transition’ phenomenon: the stages of the process to reduce maternal mortality.

| Stage 1 | MMR >1000 |

| High fertility | |

| Predominance of direct causes of maternal death with high rate of communicable diseases. | |

| Stage 2 | MMR 300–999 |

| Similar to stage 1 but greater proportion of women seeking health care. | |

| Stage 3 | MMR 50–299 |

| Fertility is variable and direct causes of mortality still predominate. More women start reaching health facilities. | |

| Stage 4 | MMR < 50 |

| Low fertility | |

| Important to address quality of care issues and eliminate delays within health systems. | |

| Stage 5 | MMR < 5 |

| Fertility very low | |

| Avoidable deaths are averted. |

MMR: maternal mortality ratio.

Source: adapted from Souza et al.3

At the October 2014 joint meeting of the International and North American Societies of Obstetric Medicine (ISOM and NASOM, respectively) in New Orleans, attendees from 23 countries had the opportunity to participate in an inaugural global obstetric medicine panel. In this paper, we summarise the presentations and discussions that took place during that panel. We highlight the experience, challenges, successes and lessons learned, of three countries – Sri Lanka, Colombia and South Africa. We also present the case of Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), which is an inspiring example of collaboration to improve maternal health. Finally, we discuss our ideas and initiatives for the future.

What is global obstetric medicine?

The term global health has varying definitions but what is central to all of them is the emphasis on health disparities in vulnerable populations and achieving equity.4 Global health analyses the underlying causes and contextual factors that determine a health issue. An essential component is the focus on solutions that vary according to available resources, political will, time frame and scope of goals.4 Along the same lines, we believe that as care providers addressing medical complications of pregnancy, our perspective must be one of global obstetric medicine.

In the media, lay and scientific literature, and major initiatives, global health is still identified with problems characteristic of “developing” or low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs).5 It is associated with the concept of risks flowing in one direction and (often paternalistic) philanthropy flowing back in the other direction.5 However, this notion of global health fails to recognise the benefits of a bidirectional flow of ideas, in which those in well-resourced settings learn from those who have made more with less and see the more severe end of the spectrum of maternal outcome. Globalisation of obstetric medicine requires us to acknowledge that global health refers to the health of an interdependent global population.5 We need to broaden our scope to include colleagues, communities and countries that do not yet have established obstetric medicine education, training or resources. We will support each other to reach vulnerable women, address health disparities, and in so doing, improve the quality of care of women in well- and under-resourced settings.

The global burden of maternal mortality and morbidity

An estimated 800 women die every day from pregnancy and pregnancy related complications.6 Maternal deaths, however, have been described as only the tip of the iceberg. For every woman who dies of pregnancy related causes, up to 30 others experience acute or chronic morbidity, often with permanent sequelae that affect their ability to function normally.7 Totally 99% of these maternal deaths and complications occur in LMICs and most are avoidable.6 Half of those deaths are due to medical causes.8 Like the obstetric population in high resourced settings, women of childbearing age in LMICs are increasingly overweight or obese and have pre-existing medical conditions. This trend is in keeping with that seen in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2010 which identified that these demographic changes are driving up premature deaths and disability from NCDs (mainly cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes).9 At the same time, some regions such as sub-Saharan Africa continue to struggle with a high burden of death and disability due to communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, diarrhoea and malaria.10 Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) states that women in LMICs often bear a triple burden of ill-health related to pregnancy and childbirth, to communicable diseases and to NCDs.11

Maternal health is intimately and reciprocally linked to NCDs as pre-existing conditions increase both maternal morbidity and mortality. Women are particularly vulnerable to NCDs given their societal and economic status in many countries. They are disadvantaged when it comes to prevention and access to care while bearing social, sexual, psychological and financial stigmatization when they are affected by NCDs.

While we predominantly focus on LMICs in this article, we need to acknowledge that vulnerable women in high resource settings face similar issues as their counterparts in LMICs. In the context of limited resources, geographical isolation, lack of health care personnel, varying language groups, and differing cultural beliefs and traditions, remote regions like Labrador and Newfoundland, and the Yukon in Canada have one of the highest rates of adverse maternal outcomes in the country, with rates that approach those in some LMICs – maternal mortality rates of 16.4 and 20.1 per 100,000 live births, respectively.12 In the US, maternal mortality and morbidity remain a challenge with the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) doubling from an estimated 12 to 28 maternal deaths per 100,000 births in the last 25 years.13 Similar to LMICs, about half of all maternal deaths in the USA are preventable.14 A recent editorial proposed that one of the key factors for the increase in maternal mortality is the increasing number of women who present at antenatal clinics with chronic conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity.15 The confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the UK found that 50–90% of maternal deaths were associated with substandard care.16

Global challenges in caring for the obstetric medicine patient

Global obstetric medicine faces several challenges. At the highest level, the global health agenda needs to recognise the growing burden of maternal morbidity and mortality due to NCDs. Political will is required to translate it to policies and action. An overarching need is health systems strengthening at the national level. Health information, referral and transport systems, together with access to qualified emergency obstetric care, are generally the weakest where the problem of pregnancy-related mortality is the greatest.17 Additionally, consistent practice and policies are needed.

The lack of skilled healthcare providers is, perhaps, one of the biggest challenges faced by obstetric medicine. In many countries, there is fewer than the WHO minimum standard of 23 skilled healthcare providers (i.e. physicians, nurses and midwives) per 10,000 population.18 Many are challenged by the difficulty of retaining healthcare workers especially in areas of high need (e.g. rural areas) due to internal and international brain drain.19 A critical concern is that healthcare workers lack required knowledge and skills due to inadequate training and lack of access to continuing education. Many healthcare workers have little or no access to basic and practical information. This is especially the case for primary and district healthcare providers.20 Several studies have shown that there is a gross lack of knowledge about the basics on how to diagnose and manage common diseases.20 Many clinicians are forced to care for pregnant patients as an extension of their care and become responsible for all aspects of obstetric care including medical complications of pregnancy without any specific training.21 With a more horizontal approach to healthcare, nurses and midwives in LMICs take on a wide variety of responsibilities related to pregnancy care and often find themselves without the appropriate knowledge and skills.22

Finally, a recent white paper by the Maternal Health Task Force found that the increasing burden of NCDs was a key priority for knowledge generation to improve maternal health in LMICs.23 Yet only a minority of the ongoing clinical research in LMICs is dedicated to medical conditions in pregnancy.24

Sri Lanka: Two decades of obstetric medicine experience

Sri Lanka has achieved a MMR of 29 per 100,000 live births, the lowest in South Asia, with infant (8 per 1000 live births) and under 5 (10 per 1000 live births) mortality rates following the same trend.25,26 These achievements are a result of a robust public health care system and sustained national commitment to free education and health. The health care system has a strong focus on preventive and curative health infrastructure and delivers comprehensive family planning, maternal and child health care services. Trained female family health workers (FHWs) implement evidence-based interventions in an integrated package of care at the community level. These workers identify and book over 95% of pregnant women for formal antenatal care (ANC) within the first trimester,27 and promote delivery in facilities, where 99% of births occur now. As such, FHWs have been critical to the success of the national Maternal & Child Health/Family Planning programme.28

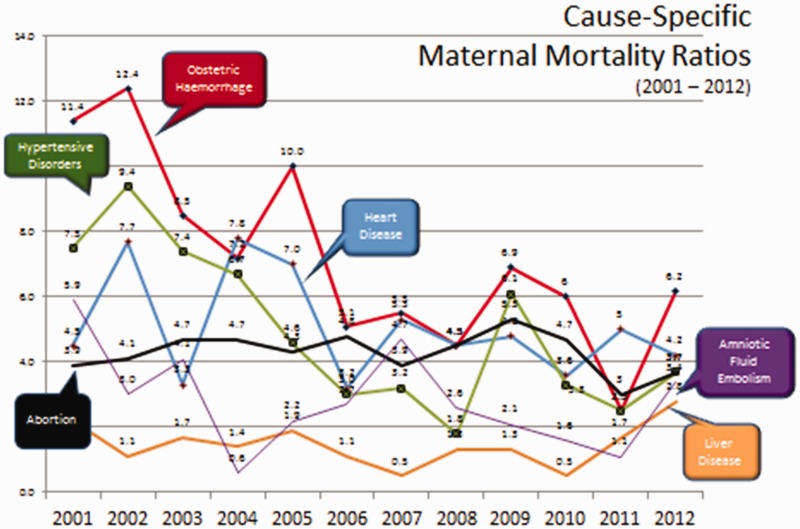

Nevertheless, there is work to be done. Although obstetric haemorrhage continues to lead the causes of maternal death and the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy also figure prominently, these direct causes of maternal death are rivalled by the indirect causes of heart disease and liver disease which have decreased to a lesser degree (or not at all) compared with direct causes (Figure 1).29 The emerging pattern of causes of maternal death alerted policy-makers and academics to the need for physician-driven management of these high-risk mothers. Although a dedicated ‘state-of-the art’ national centre for training and research in maternal medical care remains slow to be established, Sri Lanka currently has had a dedicated obstetric medical service at the Professorial Unit of the De Soysa Hospital for Women in Colombo since 1993, where care by Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Internal Medicine are integrated. Also, there is acknowledgement of the need for a multidisciplinary approach at all levels of maternity care. As such, since 1993, the Ministry of Health has appointed full-time physicians to the main maternity hospitals and endorsed the incorporation of obstetric medicine into undergraduate and postgraduate training programmes in both obstetrics and gynaecology and internal medicine. ISOM collaborated towards this goal with a local continuing medical education (CME) programme in 2007.

Figure 1.

Cause-specific maternal mortality ratios in Sri Lanka.

There has been a particular focus on maternal deaths due to heart disease. First, cardiac care in pregnancy has received greater attention by all related specialities, including a recent commitment of cardiologists to be involved in field-based reviews and consensus-building as part of clinical practice guideline development. Second, dedicated effort was applied to achieve general acceptance of guidelines to guide clinical practice. Third, the timing of maternal deaths due to heart disease has been extended to 12 months postpartum.

More generally, interested individuals have been carrying out clinical obstetric audits. Maternal death reviews have received much needed attention.30 Obstetric internal medicine physicians are now recognized stakeholders along with their obstetric anaesthetist colleagues in the death review process, at both regional and national levels. They joined the lobby to include maternal suicide as a direct cause of maternal mortality, with a greater public health approach to the maternal death investigation process. Recently, the Family Health Bureau (FHB), the focal point of maternity care in the country, collaborated with experts in maternal medicine to introduce universal screening for maternal diabetes and cardiovascular risks, and implemented a long-term follow-up strategy for high-risk women and their offspring beyond the traditional postpartum period. The next step will be to study links between chronic maternal conditions and neonatal and child health.

Colombia: Moving beyond maternal mortality

Colombia, located at the top of South America, has a MMR of 83 per 100,000 live births with an expected MMR of 45 per 100,000 live births for 2015.31 Although Colombia is not on-target to meet the MDG 5 goal of 75% reduction in maternal mortality, by 2015, the country has shown greater improvement compared with other Latin American countries, such as Venezuela and Bolivia. The decrease in the MMR in Colombia has followed both improvement in the quality of care and overall development in the country in recent years. Despite this favourable trend in overall MMR between 1990 and 2013, maternal deaths due to indirect causes have increased dramatically.32 Positioned between stages III and IV of obstetric transition,3 the country faces many of the same maternal health issues as other LMICs but at the same time, is challenged with those of well-resourced countries.

Since 2005, the maternal health branch of the Colombian Ministry of Health, the National Institute of Health (the leading entity in surveillance), and the Colombian Societies of Obstetrics, Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Maternal Fetal Medicine have undertaken an interdisciplinary approach for reducing maternal mortality through three main strategies: (i) recognition of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) as an outcome warranting attention, rather than a focus solely on maternal death; (ii) establishment of an obstetric critical care admission audit; and (iii) a national education and training programme for leading causes of maternal death and SMM.

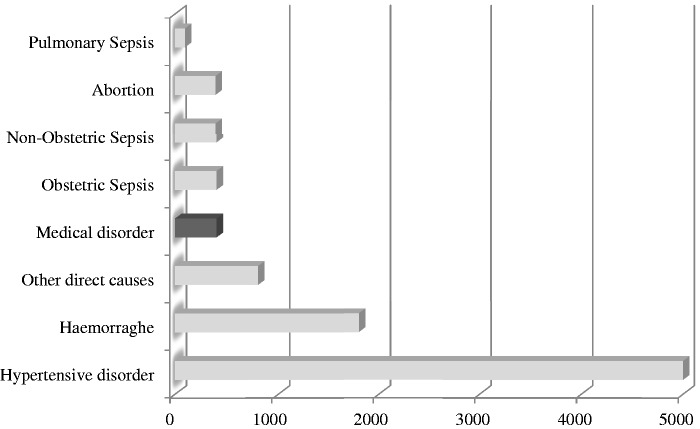

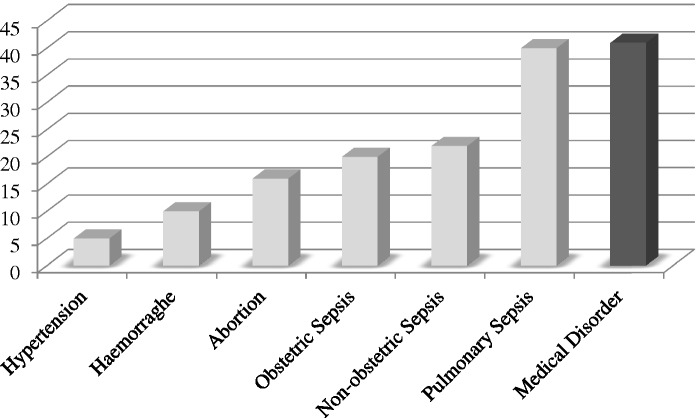

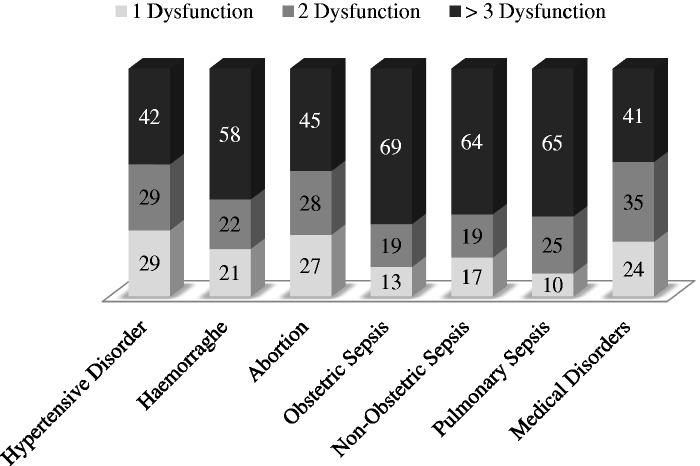

Addressing SMM as a strategy for reducing maternal death has been advocated by the WHO Maternal Morbidity Working Group (MMWG).33 As an initial step, the WHO published a classification system for the SMM, termed ‘near miss’, to describe a woman who survived a complication during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of the pregnancy ending, either through good luck or good care.34 These WHO identification criteria are based on the maternal condition diagnosed, organ dysfunction demonstrated and interventions received, such as intensive care, emergency surgery or blood transfusion. These identification criteria were adopted and implemented by Colombia. This approach has revealed that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and to a lesser degree, obstetric haemorrhage, lead the causes of SMM, with medical disorders and non-obstetric sepsis as additional important causes (Figure 2).35 However, these indirect (vs. direct) causes of SMM are associated with maternal organ dysfunction that is at least as great (Figure 3), and mortality indices that are far greater with pulmonary sepsis (Figure 4).36 A review of maternal deaths from H1N1 in Colombia suggests that a contributing factor to maternal illness and death may be a lack of recognition of the severity of maternal illness at presentation.37

Figure 2.

Severe maternal morbidity in Colombia 2013.

Figure 3.

Mortality index (MI) by cause of severe maternal morbidity in Colombia in 2012.

Figure 4.

Organ dysfunction by diagnosis of severe maternal morbidity in Colombia in 2012.

Colombia has launched a national training and educational campaign focused on three major obstetric conditions: the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, obstetric haemorrhage and sepsis (obstetric and non-obstetric). Supported by the government and non-profit organisations, educational activities include workshops and low cost simulation courses in the three states with the highest MMR: Guajira, Cordoba and Choco. The reduction in MMR has been attributed in large part to a reduction in MMR due to these three targeted conditions.

In order to further address maternal mortality due to medical disorders, Colombia needs obstetric medicine education. Awareness and advocacy in Colombia and elsewhere in Latin America will be facilitated by a network of obstetric medicine colleagues and societies.

South Africa: Triple burden of disease

South Africa has a MMR of 146.71 per 100,000 live births (2012 data), and rates have fallen by ∼30% from 2008 to 2011.38 Medical conditions in pregnancy are amongst the top five causes of maternal death, and the institutional MMR (iMMR) has been increasing steadily from 8.1 to 15.7 per 100,000 live births between 2002 and 2012.38 The trends in iMMR are the same in South Africa’s public and private health care systems (where most deliveries take place), although rates are lower in the private system. Amongst medical conditions, the biggest contributors have been cardiac and respiratory conditions (Table 2).38 Although still a major contributor, HIV/AIDS as a cause of maternal death is falling (71.7 to 55.5 per 100,000 live births) from 2008 to 2012,38 related to universal access to highly active antiretroviral therapy for all pregnant women.

Table 2.

Comparison of the iMMR of the different categories of maternal deaths in South Africa.

| Disease category | 2002–2004 | 2005–2007 | 2008–2010 | 2011–2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | ||||

| Hypertension | 27.72 | 23.85 | 24.58 | 21.6 |

| Obstetric haemorrhage | 19.51 | 18.82 | 24.91 | 23.9 |

| Pregnancy-related sepsis | 12.09 | 8.55 | 9.34 | 7.6 |

| Indirect | ||||

| Non-pregnancy-related infections | 55.0 | 66.28 | 71.29 | 53.3 |

| Medical and surgical disorders | 8.12 | 9.09 | 15.57 | 15.6 |

iMMR: institutional maternal mortality ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births).

South and southern Africa have a high rate of rheumatic heart disease. The Heart and Stroke Foundation of South Africa implemented the World Heart Federation Action Plan to reduce deaths due to rheumatic heart disease (http://www.heartfoundation.co.za/media-releases/new-action-plan-against-rheumatic-heart-disease). This plan includes detailed, register-based control programmes, making benzathine penicillin easily accessible, increasing rheumatic heart disease training centres and supporting vaccine development. There is also a national guideline on primary prevention and prophylaxis of rheumatic fever at the primary level. Despite, this, the incidence of rheumatic heart disease in adults is thought to be as high as 23.5/100,000.39 A four-year audit performed in the obstetric cardiac clinic at the Steve Biko Academic Hospital, South Africa, found that 63.5% of women of reproductive age had rheumatic heart disease and 20% had prosthetic valves.40 These women then often present in pregnancy with mitral valvular lesions, most commonly mitral stenosis, a condition that is not well-tolerated in pregnancy.

The interim report on maternal deaths for 2011 and 2012 found that most of the deaths due to medical conditions occur in tertiary and central hospitals,41 given that most women with underlying medical conditions at the time of identification already suffer from complications. All central (academic hospitals with sub-specialty services) and tertiary hospitals have dedicated cardiac clinics for obstetric patients. These clinics are usually multi-disciplinary and run by maternal–fetal medicine specialists who collaborate closely with internal medicine. In the private system, most clinics are not run in such an integrated fashion, but women do have access to obstetricians and physicians.

Our current challenge is to improve the quality of ANC so that patients have proper risk assessment at booking, particularly a good history and proper clinical examination. This can be achieved by training the key players in ANC. In the previous decade, the essential steps of managing obstetric emergencies (ESMOE) were developed based on the British Live Saving Skills course.42 It was adapted to the South African context to address issues that contribute to maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. The course is currently run in all institutions performing deliveries. As such, ESMOE may be the tool that can be used to train key players about heart disease and other obstetric medical conditions that greatly heighten maternal and perinatal risk.

The way forward in South Africa includes more practitioners in the recognized specialty of maternal–fetal medicine, as well as more dedicated practitioners in obstetric medicine, an informal specialty in South Africa. Training programmes in both specialties are much needed in South Africa to lead the way forward in delivering quality obstetric care, in private and public health care.

Lao PDR: Collaborating for better maternal health

Lao PDR is a lower-income country with a population of 6.7 million and the highest MMR in Southeast Asia at 357 (260–840) per 100,000 live births (2010 data),43,44 despite steadily declining poverty rates and rapid economic growth in the last 20 years.45 About 70% of Lao’s population lives in rural areas, where access to water and sanitation is inadequate for up to 40% of the population.44 Women and girls continue to endure unplanned childbirths, heavy workload and restricted opportunities for better education.44

The Lao PDR government has worked with development agencies to map the national landscape of maternal and child health. Maternal health indicators arising from this work have shown positive trends. According to the 2005 Lao Reproductive Health Survey,46 only one in three pregnant women had access to ANC at least once and 85% of births occurred at home. By 2012,47 one in two women had access to ANC at least once, skilled birth attendance increased to approximately 35%,45 and basic emergency obstetric and newborn care was available in every district with all major hospitals having the capacity to provide caesarean delivery. Yet, quality of services remained a challenge. Furthermore, implementation of services has followed an urban–rural hierarchy, where the proportion of skilled birth attendance in urban areas is twice the national average and over six times that in remote rural areas.45

Lao has been the most heavily bombed country per capita, with an average of one bomb load every 8 min, 24 h a day, between 1964 and 1973.48 After the war, Lao PDR had an estimated 37 physicians, and for the ensuing 20 years, lacked the capacity and infrastructure to support the medical school, relying on foreign aid to train a handful of specialists abroad, most of whom would serve the urban population. The University of Calgary and Lao University of Health Sciences Collaboration started in the early 2000s, aiming to improve the medical training of Lao physicians and quality of care for the Lao people. Initially, a new undergraduate problem-based learning curriculum was implemented followed by a family medicine specialist training programme 10 years ago, in response to the need to train skilled primary care physicians who could become community health advocates and leaders at the smaller district and provincial level. As of 2014, University of Calgary faculty collaborate with over 170 Family Medicine graduates, 65% of whom work at the district and provincial levels, and respond to their evolving medical education needs. The faculty supports an annual family medicine conference and an “Adopt-A- Region” initiative, through which University of Calgary faculty provide longitudinal clinical and educational mentorship at designated training sites.

In 2013, the Lao PDR government legislated universal maternal and under-five child health care in an effort to meet MDGs 4 and 5.49 For Family Medicine graduates, particularly at the small district hospital level, the number of deliveries increased 10–20 fold, which meant that the number of deliveries at their district hospitals went from 1–2 to 30–40 deliveries per month. To support graduates with the increased volume of patients, the University of Calgary faculty and Lao colleagues developed a series of didactic workshops on maternal care, which included partogram use and care of antepartum and postpartum haemorrhage and the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Knowing that single interventions for specific clinical diagnoses do not result in significant reductions in maternal mortality,50 capacity building in the Lao setting should emphasize skilled birth attendance, emergency obstetric care and an enabling environment, with adequate infrastructure, essential drugs and a functional referral system.51 The University of Calgary Lao project works towards this goal by enhancing practical knowledge (such as how to administer magnesium sulphate), supporting knowledge transfer from family medicine graduates to other potential skilled birth attendants, and effecting change in their environments as they assume leadership roles. The 2013 CME pre-eclampsia workshop resulted in practical action as discussion around the WHO list of essential medicines52 prompted Family Medicine graduates to ensure these drugs were available at their district hospitals. For decades now, our Lao colleagues have relied on medical textbooks in foreign languages, hampering knowledge dissemination. Translation of teaching materials to Lao language has helped immensely for rolling out reproducible, portable health interventions like Helping Babies Breathe. Supporting Lao colleagues to develop their own teaching materials in Lao language has been of utmost importance, as English is not a universal language, and in one single room the primary language in which our Lao colleagues have acquired most of their medical training includes French, Russian, German, Spanish, Thai and Korean.

The longitudinal relationship between the University of Calgary faculty and local Lao practitioners has allowed us to build relationships, create comfort between colleagues, enhance our credibility as collaborators and most importantly, develop cultural sensitivity. Next steps include developing a Family Medicine maternal health curriculum pertinent to the evolving health landscape in Lao PDR.

The way forward

There is a growing appreciation amongst international organizations that their perspective is not global enough. As reflected by the panel discussions, these thoughts were front and centre at the 2014 ISOM and International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) meetings in New Orleans, USA where it was emphasized that the vast majority of maternal death and disability occurs in LMICs, and that most could be avoided through health system strengthening.

In response, three new initiatives were launched: a joint Global Health Committee focused on initiatives in LMICs, a Preeclampsia Foundation funding opportunity linking a mentor in a high-income country with one in a LMIC, and formation of the global obstetric medicine group, a small group within ISOM that will be part of the joint ISSHP–ISOM Global Health Committee and lead efforts in global maternal health within ISOM. The panel discussions presented here have highlighted the importance of leadership in obstetric medicine in LMICs where ∼25% of women die from indirect causes.8

These initiatives will do as much (or more) for those of us in well-resourced settings as they will for those in under-resourced settings. Women who die in LMICs often do so because they either never reach health care facilities, or when they do, they are beyond salvage. We can learn from our colleagues who have regular experience with the severe end of the obstetric medicine spectrum and maternal death. Also, we can learn from their creative responses to challenging work environments – termed ‘reverse innovation’53 to apply these lessons to our settings where similar challenges may exist. In life and in medicine, necessity is the mother of invention.

How can we forge these links? Cohesiveness and community have been promoted by the OB Med ListServ started by Michael Carson, USA (http://lists.obmed.org/listmanager/listinfo/obmeddiscussion and then sign in or sign up). Any member can contact the ListServ group with questions about direct patient care of any type. Participants may respond to emails or follow along. The beauty of this resource is its simplicity and flexibility. Additional strengthening of our global obstetric medicine community is being pursued by reaching out to LMIC colleagues through the Maternal Health Task Force and WHO blogs and newsletters. Recently, the ISOM Global Obstetric Medicine group sent out a scoping survey, to which over 150 responses were received from obstetricians and physicians in 39 countries, 29 of which are LMICs in Africa, Latin America and Asia. There was overwhelming interest and enthusiasm in building a global network of experts committed to medical complications of pregnancy. Through the survey, we learned that in many of these countries there are specialists who focus on medical complications of pregnancy, which generally are obstetricians (80–90%) and less often physicians (55%) or anaesthetists (30%). Interestingly, two-thirds of the respondents were aware of national societies that focus on maternal medicine, but very few of the colleagues contacted apart from those already on the OB Med ListServ knew about international societies (such as the ISOM and ISSHP). A follow-up survey is planned to explore more deeply the challenges our colleagues in LMICs face and what steps need to be taken to address those challenges.

The Global Library of Women’s Medicine (GLOWM) is the educational platform for the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO), and provides open-access peer-reviewed evidence for health care providers in well- and under-resourced settings. A FIGO textbook on the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy is underway, but we need to think ahead to initiatives on sepsis, cardiorespiratory disease, and other major causes of maternal death that fall within the scope of practice of obstetric medicine (www.GLOWM.com). Other educational initiatives have been completed or are underway. Annabelle Cumyn (acumyn@gmail.com) and colleagues in Canada are putting together an open-access, online collection of teaching cases. LMIC-input will be invaluable, including conditions of particular regional importance (e.g. malaria). Also, it will be important to work on increasing access to other resources that are currently restricted to members, such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), UK. This could be via the ISOM website that is currently being updated.

Medical problems of pregnancy are an ongoing cause of morbidity and mortality in high-, middle- and low-income countries. In this paper, we have highlighted the GBD from maternal medical problems and included four different country examples. A key challenge remains to accurately quantify the burden of obstetric medical disease in LMICs. An ambitious but much needed step is to design a multi-country study looking at the obstetric medicine conditions that cause maternal morbidity and mortality, the avoidable factors and deficiencies in care. In the meantime, in order to support physicians and obstetricians in countries without established obstetric medicine training, initiatives such as facilitating consultant exchanges between different units are amongst the projects currently being considered. As a community, we can address global challenges by working together to develop educational, institutional and practical solutions. As we look towards the 2016 ISSHP and 2017 ISOM meetings, please consider that lofty initiatives will move forward by personal support from membership. Fruitful collaborations are so often borne of personal relationships, often established at our international meetings. ISOM President, Sandra Lowe, makes it her personal practice to get to know one new person at each meeting in her ongoing effort to build a community of like-minded individuals in obstetric medicine. Those relationships will foster information sharing related to direct patient care, teaching resources, reviews and research projects. Please consider taking one personal step to address closer global relationships within obstetric medicine prior to our next international meeting.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editorial board for the invitation to present this work.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

None required.

Guarantor

TF

Contributorship

TF conceptualized the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lowe S. Editorial. Obstet Med 2014; 7: 97–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Countdown to 2015 launches the 2012 report. http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/countdown_2012_report/en/ (2012, accessed January 2015).

- 3.Souza JP, Tuncalp O, Vogel JP, et al. Obstetric transition: the pathway towards ending preventable maternal deaths. BJOG 2014; 121: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell RM, Pleic M, Connolly H. The importance of a common global health definition: how Canada’s definition influences its strategic direction in global health. J Glob Health 2012; 2: 010301–010301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frenk J, Gomez-Dantes O, Moon S. From sovereignty to solidarity: a renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. Lancet 2014; 383: 94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/ (accessed January 2015).

- 7.Geeta N, Switlick K, Lule E. Accelerating progress towards achieving the MDG to improve maternal health: a collection of promising approaches, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2005, pp. 4–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2: e323–e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global Burden of Disease. http://www.thelancet.com/themed/global-burden-of-disease (accessed January 2015).

- 10.Global Burden of Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 385: 117–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. PMNCH Knowledge Summaries: #15 - non-communicable diseases. http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/maternal/knowledge_summaries_15_noncommunicable_ diseases/en/ (accessed January 2015).

- 12.Public Health Agency of Canada. Maternal Mortality in Canada 2011. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/aspc-phac/HP10-19-2011-eng.pdf (accessed 1 March 2015).

- 13.Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2013/en/.

- 14.Main EK, Menard MK. Maternal mortality: time for national action. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 122: 735–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal P. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ 2015; 93: 135–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG 2011; 118: 1–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anand S, Barnighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet 2004; 364: 1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byass P. The unequal world of health data. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000155–e1000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prata N, Passano P, Sreenivas A, et al. Maternal mortality in developing countries: challenges in scaling-up priority interventions. Women's Health 2010; 6: 311–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pakenham-Walsh N, Bukachi F. Information needs of health care workers in developing countries: a literature review with a focus on Africa. Hum Resour Health 2009; 7: 30–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe S, Nelson-Piercy C, Rosene-Montella K. The role of obstetric medicine in holistic care. Obstet Med 2009; 2: 1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Enhancing nursing and midwifery capacity to contribute to the prevention, treatment and management of non-communicable diseases. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/observer12.pdf (2015, accessed January 2015).

- 23.Maternal Health Task Force. Critical maternal health knowledge gaps in low and middle income countries for post 2015: researchers’ perspectives. 2015. http://www.mhtf.org/document/critical-maternal-health-knowledge-gaps-in-low-and-middle-income-countries-for-post-2015-researchers-perspectives/ (2015, accessed March 2015).

- 24.Merriel A, Harb HM, Williams H, et al. Global women’s health: current clinical trials in low- and middle-income countries. BJOG 2015; 122: 190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The World Bank. Maternal Mortality Ratio. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT (accessed January 2015).

- 26.UNICEF. Sri Lanka. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/sri_lanka_statistics.html (accessed January 2015).

- 27.Dulitha F, Anoma J and Vinitha K. Pregnancy—reducing maternal deaths and disability in Sri Lanka: national strategies. Br Med Bull 2003; 67: 85–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Family Health Bureau (FHB). ‘Maternal & Child Morbidity & Mortality Surveillance Unit’. http://www.familyhealth.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=52&Itemid=166&lang=en (2015, accessed February 2015).

- 29.Haththotuwa HR, Attygalle D, Jayatilleka AC, et al. Maternal mortality due to cardiac disease in Sri Lanka. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009; 104: 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathur A, Awin N, Adisasmita A, et al. Maternal death review in selected countries of South East Asia Region. BJOG 2014; 121: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 980–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Intarut N, et al. Indirect causes of severe adverse maternal outcomes: a secondary analysis of the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG 2014; 121: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Firoz T, Chou D, von Dadelszen P, et al. Measuring maternal health: focus on maternal morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2013; 91: 794–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Say L, Souza JP, Pattinson RC. Mortality WHOwgoM, Morbidity c. Maternal near miss–towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 23: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Instituto Nacional de Salud. Informe del evento morbilidad materna extrema, Colombia, 2013. www.ins.gov.co (accessed March 2015).

- 36.Instituto Nacional de Salud. Informe del evento morbilidad materna extrema, Colombia, 2013. www.ins.gov.co (accessed March 2014).

- 37.Rojas-Suarez J, Paternina-Caicedo A, Cuevas L, et al. Maternal mortality due to pandemic influenza A H1N1 2009 virus in Colombia. J Perinat Med 2014; 42: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattinson R, Fawcus S, Moodley J; for the National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths. Tenth interim report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths South Africa 2011 and 2012. www.doh.gov.za (accessed July 2013).

- 39.Silwa K, Carrington M, Mayosi BM, et al. Incidence and characteristics of newly diagnosed rheumatic heart disease in urban African adults: insights from the Heart of Soweto. Study Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soma-Pillay P, MacDonald AP, Mathivha TM, et al. Cardiac disease in pregnancy: a 4 year audit at Pretoria Academic Hospital. S Afr Med J 2008; 98: 553–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths. Saving mothers 2008-2010. Fifth report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths South Africa. Short Report 2011 and 2012. www.doh.gov.za (2011, accessed January 2015).

- 42.ESMOE. Frank K, Lombaard H, Pattinson RC. Does the implementation of the Essential Steps in Managing Obstetrics Emergencies (ESMOE) training package result in improved knowledge and skills in managing obstetric emergencies? S Afr J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 15: 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Bank. Lao PDR Country Profile 2015. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lao/overview (2015, accessed February 2015).

- 44.WHO. Global Health Observatory April 2014. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-LAO?lang=en (2014, accessed February 2015).

- 45.UNDP. The Millennium Development Goals Progress Report for the Lao PDR 2013. In: Programme UND. Vientiane, Lao PDR: Government of the Lao PDR and the United Nations, 2013.

- 46.39. Boupha S, Soukasavath P, Chanthalanouvong T, et al. Lao Reproductive Health Survey 2005. In: LAO/02/P07 UP (ed) UNFPa Project LaO/02/P07: strengthening the database for population and development planning. Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR: National Statistics Center (NSC), 2007, p.200.

- 47.Lao PDR Ministry of Health and Lao Statistics Bureau. Lao Social Indicator Survey. Vientiane, Lao PDR: Partner Agencies UNICEF, UNFPA, LuxGov, USAID, AusAID, SDC, UNDP, WHO, JICA, UNAIDS, WFP, 2012.

- 48.UN. United Nations in the Lao PDR: reduce the impact of unexploded ordnance (UXO), 2010.

- 49.Government of Lao PDR. Prime Minister’s Decree No. 178/PM on the implementation of free delivery and free health care for children under 5 years old. 2012.

- 50.Campbell OM, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet 2006; 368: 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kongnyuy EJ, Hofman JJ, van den Broek N. Ensuring effective essential obstetric care in resource poor settings. BJOG 2009; 116: 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO. WHO – priority medicines for mothers and children 2011. In: World Health Organization (WHO): Department of Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical Policies. Geneva, 2011.

- 53.Syed SB, Dadwal V, Martin G. Reverse innovation in global health systems: towards global innovation flow. Globalization Health 2013; 9: 36–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]