Abstract

Background

Lateral end of clavicle fractures can be a challenge, with a 20% to 30% non-union rate if treated non-operatively. Several operative options exist, each having their own merits and some having potential disadvantages. The Minimally Invasive Acromioclavicular Joint Reconstruction (MINAR®) (Storz, Tutlingen, Germany) set uses an Orthocord (Depuy Synthes Mitek, Leeds, UK) suture and two Flip Tacks (Storz) via a transclavicular-coracoid approach to reconstruct the coracoclavicular ligaments.

Methods

Referrals were made to two senior surgeons at separate institutions regarding Robinson Type 3 fractures of the lateral end of the clavicle. All patients were treated with MINAR implant via a minimally invasive approach. Two-year follow-up was obtained using the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) and the Quick DASH (Disability of the Arm Shoulder and Hand) score.

Results

Sixteen cases of acute fractures of the lateral end of the clavicle were included in this series. At final follow-up, the mean OSS was 44.75 (range 35 to 48) and the median Quick DASH score was 2.3 (range 0 to 35.9). Fifteen patients achieved bony union (one asymptomatic non-union) and there were no complications or re-operations.

Conclusions

The MINAR is reproducible and safe when treating lateral end of clavicle fractures. We consider that, over the short- to mid-term, it achieves results equivalent to those for other implants.

Keywords: Clavicle fractures, complications, DASH, hook plates, MINAR, Oxford Shoulder Score, Robinson Type 3

Introduction

There are multiple classifications described for lateral end of clavicle fractures, including those of Allman,1 Craig2 and Neer.3 Robinson further classified clavicular injuries and defined the lateral one-fifth of the clavicle as Type 3.4 There is a 20% to 30% non-union rare if treated non-operatively.5–7

Several operative methods allowing bony union and coracoclavicular ligament healing exist, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. These include:

Kirschner wires or coracoclavicular screws, which are cheap but have been documented to migrate into the chest8–10 or undergo fatigue fracture, respectively.11,12

lateral end of clavicle locking plates7 (separate to hook plates), allowing accurate reconstruction of bone fragments.

lateral end of clavicle modified tension banding techniques with transacromial Kirschner wires or suture anchors.13,14

hook plates, which are not only very reliable for union, but also can have complications, including rotator cuff tear,15 impingement pain16 and need for removal.17–19

Robinson et al. reported favourable results with an endobutton technique when reconstructing the coracoclavicular ligaments in clavicle fractures. A mean Constant score of 87.1 and a median Disability of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score of 3.3 was reported at 1 year.20 Similar results have been replicated for ACJ reconstructions when using the Minimally Invasive Acromiocalavicular Joint Reconstruction (MINAR®; Storz, Tutlingen, Germany) set in Germany with a mean Constant score of 94.1 at 23.3 months.21

The present study aimed to demonstrate an acceptable Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) and DASH score between surgeons at different district general hospitals, following MINAR for lateral end of clavicle fractures.

Materials and methods

Patients were referred to the two senior surgeons at separate institutions with displaced Robinson Type 3 fractures of the lateral end of the clavicle. In each case, there was more than 50% displacement, indicating coracoclavicular ligament rupture. Referral sources included accident and emergency departments or inhouse fracture clinics. No tertiary referrals were received. Diagnosis was based on clinical and radiological (plain X-ray) findings. All patients were operated on within a 2-week period.

Over a 2-year period, data were collected from the institutions regarding patient demographics, function and outcome scores, including the OSS and the Quick DASH score.

All procedures were performed under the direct care of the named investigators.

Movement and physiotherapy was commenced after the first clinic appointment at 2 weeks. No over shoulder height range of movement was allowed for the first 6 weeks postoperatively.

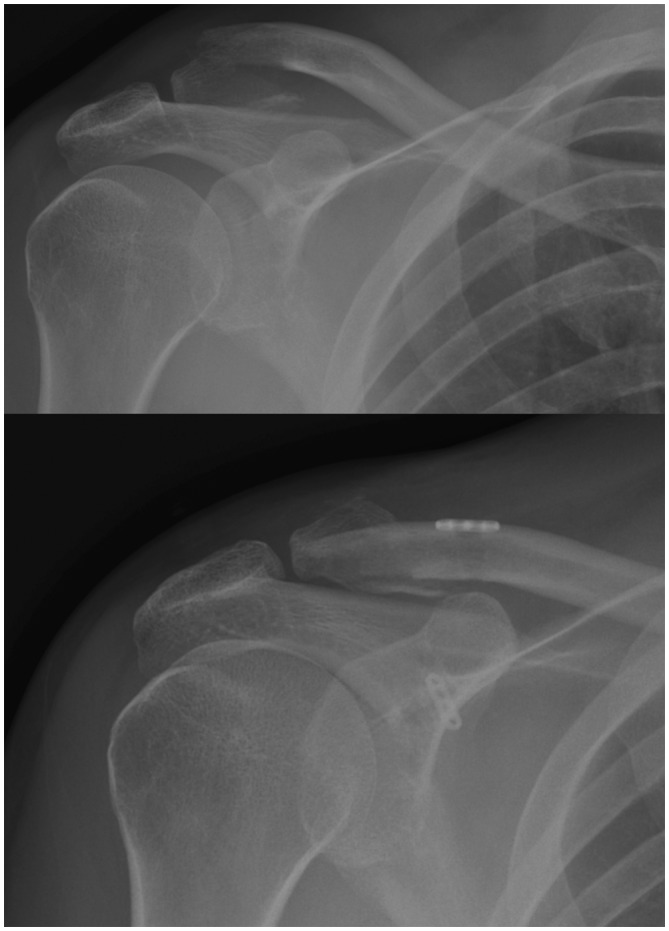

Routine follow-up occurred in the outpatients department at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months and 1 year or until radiological union and full return of acceptable shoulder function was observed. A full return to function was our primary goal. Union was defined clinically and radiographically as the absence of pain and presence of new bone or consolidating callus on plain anteroposterior X-ray.

Surgical technique

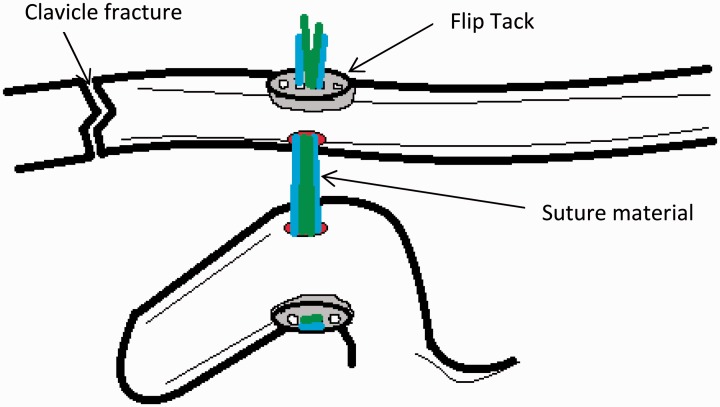

Using a beach-chair position (under general anaesthesia) and with prophylactic antibiotics according to local policy, minimally invasive approaches were used over the lateral end of the clavicle and the coracoid to facilitate exposure. The superior acromioclavicular ligaments are protected and or reconstructed using this technique where required. The clavicle was reduced. Both centres utilized the MINAR with number 2 Orthocord (Depuy Synthes Mitek, Leeds UK) threaded twice through the Flip Tacks (Storz) and then tied over the clavicular Flip Tack after reduction (Figures 1 and 2). The dedicated Storz instrumentation was used with this technique to avoid an eccentric hole in the coracoid that would result in pull out of the Flip Tack or fracture of the coracoid.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the MINAR® (Storz).

Figure 2.

Pre-operative and discharge radiographs of a clavicle fracture treated using the MINAR® (Storz).

Patients were either discharged the same day or had a single overnight stay and left hospital with the arm immobilized in a sling for 2 weeks.

Results

Sixteen cases met the Robinson Type 3 criteria, which were acute fractures (i.e. less than 2 weeks old). Of these, 13 were male and three were female. The ages ranged from 16 years to 49 years.

The cases could be further subdivided into Robinson Type 3B1 (n = 14) and Robinson Type 3B2 (n = 2).

The mean time at follow-up was 48 weeks (range 6 weeks to 113 weeks). The outlier of 113 weeks was a result of an initial loss of follow-up but did not re-present as a problem. At final follow-up, the mean OSS was 44.75 (range 35 to 48), with a median Quick DASH score of 2.3 (mean 8; range 0 to 35.9).

Fifteen patients had radiological evidence of bony union. This took place in the interval from 6 weeks to 10 weeks.

The remaining patient had been discharged at the 6-week period on request with no callus formation but was pain free and has not returned with failure of the implant.

There were no re-operations amongst this group and no complications as far as we are aware. Complications would encompass neurovascular damage, non-union, displacement or failure of the implant.

Discussion

Robinson Type 3 injury to the lateral part of the clavicle is uncommon and occurs as a result of a direct high energy impact to the shoulder itself. Our patient cohort demonstrated that typically young, active indiviuals and those suitable for employment sustain these injuries. Being such an age increases the demands of not only the service provided, but also the implant and its longevity.

It is imperative that any surgical procedure provides stability and union to facilitate a quick return to work and leisure activities of a normal adult, without the need for further surgery. We feel that our results reflect this ambition.

There has been wide use of the hook plate over the last 20 years for such injuries. Three recent studies15–17 have all used the Constant and Murley Score over both the short and medium term to analyze the hook plate (Table 1). Despite the lower levels of impingement recorded, all of the plates in these studies (except one) were still removed,17–19 after successful union was achieved.

Table 1.

| Taneja et al.16 (2009) | Tiren et al.17 (2012) | Tambe et al.15 (2012) | Present study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Prospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective |

| Number of patients | 37 patients | 28 patients | 18 patients | 16 patients |

| Indication | ACJ dislocations – 33 Fractures – 4 | Fractures – acute | Fractures – 15 acute | Fractures – 16 acute |

| Impingement level | 18.9% impingement | 32% impingement | Not listed | Nil |

| Outcome scores | Constant mean: 92 (72 to 98) | Constant mean: 97 (68 to 100) | Constant mean: 88.5 (63 to 100) | OSS mean: 44.75 (35 to 48) |

| Other complication | One ACJ instability One adhesive Capsulitis | 25% subacromial osteolysis One superficial wound infection | Five acromial osteolysis Two non-unions One deep infection | Nil |

ACJ, acromioclavicular; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score.

A mean follow-up of our cohort at almost 1 year after surgery demonstrates the short- and intermediate-term success of the operation. The range of follow-up appointments is dramatic as a result of outliers at each end of the spectrum. There was evidence of radiological union at as little as the 6-week period. This was defined as new cortical bone formation on three out of four cortices.

The observed Quick DASH scores are sufficiently low that minimal disability is observed in this group after using the MINAR technique. The median Quick DASH score observed in our series2,3 is comparable to that of the series published by Robinson et al.,3 indicating the reproducibility of results using a minimally invasive ‘endobutton-type technique’.20

More recently, Soliman et al. have published a series of 14 patients using an under-coracoid-around-clavicle (UCAC) technique using an ethibond suture without drill holes.22 Although not directly comparable to our own results, they reported similar success, with 13 bony unions and a Constant score of 96.07.

The OSS values observed in the present study reflect that the majority of the patients have satisfactory shoulder function and do not require any further treatment.

The absence of hardware failure, complications or need for second surgery makes this technique for Robinson Type 3 fractures appealing.

Conclusions

Although lateral end of clavicle fractures are relatively uncommon, they tend to occur in younger patients who have higher demands both at work and recreationally. Therefore, we consider that a surgical technique used to prevent the complications of malunion and non-union should be quick, inexpensive, reproducible and without the need for further surgery or lead to complication. Our results suggest that this can be achieved and that the MINAR is equivalent in efficacy to other implants.

We have been able to demonstrate that the MINAR, when used on Robinson Type 3 lateral end of clavicle fractures, achieves results that are favourable as evaluated by both the Quick DASH score and OSS. Our results are equivalent to that of surgeons in other series, and we therefore consider that this technique is reproducible, reliable and safe.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Allman FL. Clavicle fractures: Allman classification. JBJS (A) 1967; 49: 774–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig EV. In: Neer CS (ed.) Shoulder reconstruction. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company, 1990: pp.363–420.

- 3.Neer CS. Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1968; 58: 43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson CM. Clavicle fractures: Robinson classification. JBJS (Br) 1998; 80: 476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson M, Cairns D. Primary nonoperative treatment of displaced lateral fractures of the clavicle. JBJS Am 2004; 86: 778–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Meijden OA, Gaskill TR, Millett PJ. Treatment of clavicle fractures: current concepts review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21: 423–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashif Kahn LA, Bradnock TJ, Scott C, Robinson M. Fractures of the clavicle. JBJS Am 2009; 91: 447–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao FC. Treatment of distal clavicle fracture using Kirschner wires and tension band wires. J Trauma 2001; 51: 522–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazel R. Migration of K-wire from the shoulder region into the lung. J Bone J Surg (Am) 1943; 25: 477–83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regel JP. Intraspinal migration of a Kirschner wire 3 months after Clavicular fracture fixation. Neurosurg Rev 2002; 25: 110–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng ZJ. Surgical treatment of distal clavicle fracture associated with coracoclavicular ligament rupture using a cannulated screw fixation technique. J Trauma 2006; 60: 1358–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi H. Results of Bosworth method for unstable fractures of distal clavicle. Int Orthop 1998; 22: 366–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rijal L, Sagar G, Joshi A, Joshi KN. Modified tension band for displaced type 2 lateral end of clavicle fractures. Int Orthop 2012; 36: 1417–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin SJ, Roj KJ, Kim JO, Sohn HS. Treatment of unstable distal clavicle fractures using two suture anchors and suture tension bands. Injury 2009; 40: 1308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan HL, Zhao JK, Qian C, Shi Y, Zhou Q. Clinical results of treatment using a clavicular hook plate versus a T-plate in Neer type ii distal clavicle fractures. Orthopedics 2012; 35: E1191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meda PVK, Machani B, Sinopidis C, Braithwaite I, Brownson P, Frostick SP. Clavicular hook plate for lateral end fractures – a prospective study. Injury 2006; 37: 277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tambe AD, Motkar P, Qamar A, Drew S, Turner SM. Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle: results of hook plating of the clavicle. JBJS (Br) 2012; 94B(Suppl II): 30–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taneja T, Zaher D, Koukakis A, et al. Clavicular hook plate: not an ideal implant. JBJS (Br) 2009; 91B(Suppl I): 11–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiren D, van Bremmel AJM, Swank DJ, van der Linden F. Hook plate fixation of acute displaced lateral clavicle fractures: mid-term results and a brief literature overview. J Orthopaed Surg Res 2012; 7: 2–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson CM, Akhtar MA, Jenkins AP, Sharpe T, Olabi RB. Open reduction and endobutton fixation of displaced fractures of the lateral end of the clavicle in younger patients. JBJS (Br) 2010; 92B: 811–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen W, Wellmann M, Rosslenbroich S, Zantop T. [Minimally invasive acromioclavicular joint reconstruction (MINAR)]. Oper Orthop Traumatol 2010; 22: 52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soliman O, Koptan W, Zarad A. Under-coracoid-around-clavicle (UCAC) loop in type II distal clavicle fractures. Bone Joint J 2013; 95B: 983–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]