Abstract

We present the first ever case report of a floating clavicle with a unique combination of a posterior sternoclavicular joint dislocation and an associated grade III acromioclavicular joint dislocation. We treated this injury surgically by stabilizing both ends of clavicle using a polyester surgical mesh device (LockDown™; Mandaco 569 Limited, Redditch, UK; previously called the Nottingham Surgilig).

Keywords: Bipolar clavicle dislocation, floating clavicle, sternoclavicluar joint stabilization

Introduction

The ‘floating clavicle’ or dislocation of both ends of the clavicle is an extremely rare injury resulting from high-energy trauma. This injury was first described by Porral in 1831.1 Subsequently, there have been at least 40 case reports in the literature, some of which are small case series, with all reporting an anterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) and a posterior dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ).2–4

We present the first ever case report of a floating clavicle with a unique combination of a posterior SCJ dislocation and an associated grade III ACJ dislocation. We treated this injury surgically by stabilizing both ends of clavicle using a polyester surgical mesh device (LockDown™; Mandaco 569 Limited, Redditch, UK; previously called the Nottingham Surgilig).

Case Report

A 51-year-old right-hand dominant male cyclist was hit by a car at a speed of 30 miles per hour. He was thrown from his bicycle onto the bonnet of the car, landing on the lateral aspect of his right shoulder. He was taken to the local emergency department with an isolated injury to his right shoulder girdle, with no neurovascular compromise.

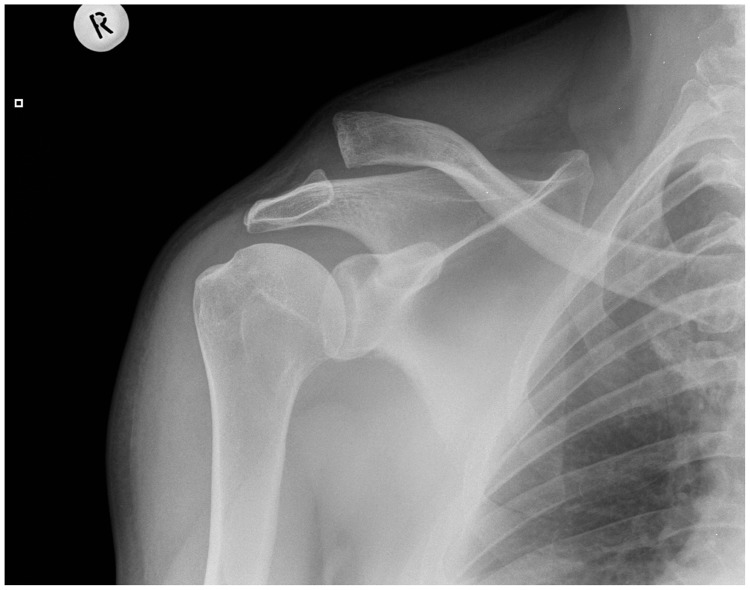

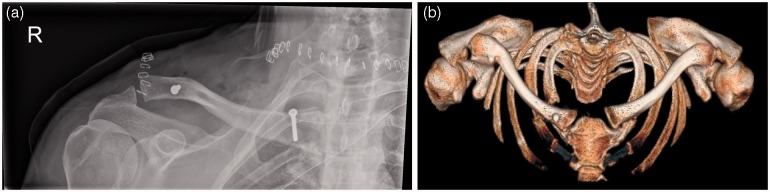

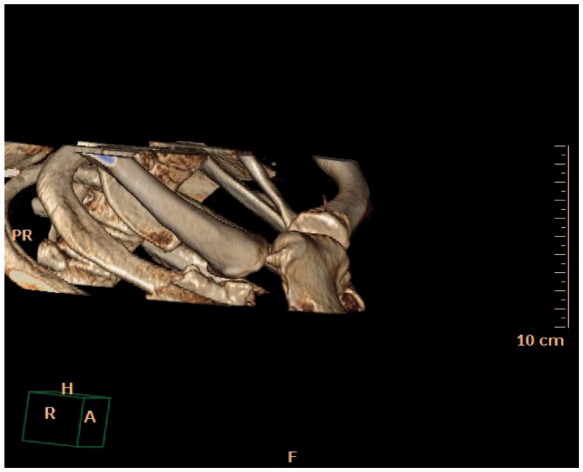

Initial radiographs of his shoulder revealed an obvious ACJ dislocation (Figure 1) and he was discharged from the emergency department with a follow-up appointment for the next local fracture clinic. He underwent further imaging at a subsequent orthopaedic consultation (Figure 2) and was then referred to our unit 3 weeks after the injury. On examination, he had a depression (hollowing) at the medial end of the clavicle, which is typically seen in posterior SCJ dislocation.

Figure 1.

ACJ dislocation.

Figure 2.

Posterior SCJ dislocation seen on 3D CT.

Surgical technique

Our standard technique for sternoclavicular joint stabilization involves looping the polyester surgical mesh device (LockDown) under the first rib before attaching it to the medial end of the clavicle. Because the first rib was fractured at the costochondral region, this technique was modified, as described below. The patient was placed in the beach chair position with the head secured. A necklace-type incision was made 3 cm above the suprasternal notch. The clavicular head of the sternomastoid was detached, leaving a small cuff at the clavicular insertion to facilitate the repair during closure. When the SCJ was exposed, we noted rupture of the anterior capsule and the intra-articular disc ligaments and a posteriorly displaced medial end of the clavicle. The medial end of the clavicle was reduced back into the joint by holding it with a pointed towel clip and levering it anteriorly using a Bristow bone elevator. The joint was found to be grossly unstable and hence it was decided to proceed with stabilization.

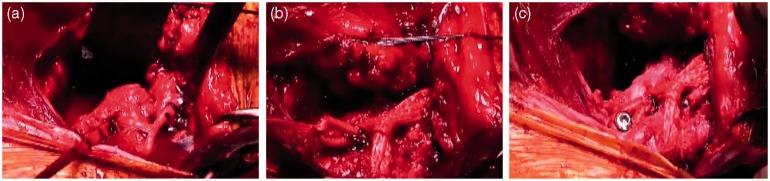

A malleable copper retractor was placed behind the medial end of the clavicle to protect the posterior neurovascular structures. Using a 4.5-mm drill, the first drill hole was made in the medial end of clavicle, approximately 1 cm lateral to the medial joint surface in an oblique direction exiting superiorly in the clavicle. The metal leader of the LockDown length gauge was introduced from outside in and the metal leader was then passed under the medial end of clavicle, to form a loop. The second drill hole was made in the manubrium sternum with the 4.5-mm drill, protecting the posterior structures with the retractor and exiting superolaterally in the sternum. The length of LockDown required was determined using the gauge (Figure 3a). The polyester surgical mesh device was now passed through the drill hole in the medial end of the clavicle and then passed under medial end of the clavicle. The hard loop of the LockDown was then passed through the soft loop to encircle the medial end of clavicle. The LockDown was then passed through the drill hole in the sternum from outside in and then passed from inside out through the medial end of the clavicle. The LockDown was then tensioned across the medial end of clavicle and the sternum (Figure 3b). The hard loop of the device was then anchored to medial end of the clavicle using one 3.5-mm cortical screw with a washer (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

(a) Lockdown length gauge, (b) Lockdown passed through the drill holes in the sternum and medial clavicle and (c) Stabilised SCJ.

ACJ stabilization

The acromioclavicular joint injury was treated surgically with the LockDown device using a standard technique.5,6

Postoperative management

X-rays and computed tomagraphy scans confirmed adequate reduction (Figure 4). The patient was managed with a broad arm sling for 3 weeks, followed by full mobilization. Sports and strenuous activities were delayed for 3 months. The patient was followed up at 6 weeks and 6 months. Oxford, Constant and Nottingham Clavicle scores were recorded at follow-up.7–9 At 6-month follow-up, he was more-or-less back to normal function with a full range of motion. His pre-operative Constant score was 41 out of 100 and his Oxford Shoulder Score was 5 out of 48. His 14-month postoperative Constant score was 96 out of 100, his Oxford Shoulder Score was 46 out of 48 and his Nottingham Clavicle score was 90 out of 100.

Figure 4.

(a) X ray post ACJ and SCJ stabilisation and (b) 3D CT image post stabilisation.

Discussion

The SCJ is an incongruous, diarthroidal joint. The stability of the joint comes from the surrounding ligaments and the capsule. The posterior SCJ capsule is the most important structure preventing anterior and posterior translation.10,11 SCJ dislocations are uncommon and usually present with anterior dislocation.12,13 Posterior SCJ dislocation was first described by Sir Astley Cooper in 1824 and it can present with very subtle clinical signs. One in three cases present with compression symptoms of the retrosternal structures, which can be life threatening.14,15 Dislocation of both ends of the clavicle is an extremely rare occurrence, resulting from a high-velocity injury. Subsequent to its initial report by Porral in 1831, there have been several reports of floating clavicle. In all of the cases reported so far, the dislocation is anterior at the SCJ and posterior at the ACJ.4

The mechanism of injury in the bipolar dislocation of the clavicle is complex, resulting from a violent blow to the lateral aspect of the shoulder or a heavy compression with an associated torsion of the trunk.16,17 Biomechanical studies have shown that the force required to dislocate the SCJ posteriorly is 50% higher than the force needed for anterior dislocation.11,18 Initial diagnosis can be difficult and plain X-rays are usually inconclusive.19 Specialized views, such as the Serendipity view, Hobbs view or Heinig’s view, may help in diagnosis.20–23 A computed tomography scan remains the gold standard imaging method for diagnosis.

Controversy still exists about the management of SCJ dislocation. Closed reduction is performed using an abduction traction technique under general anaesthesia24 and can be successful if performed within 48 h. Unstable posterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint requires open reduction and surgical stabilization. Chronic instability can lead to vascular injury over time.25,26

Stabilization of the SCJ is a rare procedure and it is important to recognize the posterior anatomical relationship of the sternoclavicular joint. It has been recommended that a cardiothoracic surgeon remains on standby during the procedure.20 Various surgical techniques for stabilization of the SCJ have been reported in the past and these include fixation with screws, Steinman pins and external fixation devices27 but, more recently, tendon grafts and synthetic materials have been used, with the aim of reconstructing the costoclavicular ligament.28–30

In the present case, once the SCJ was stabilized, the ACJ was assessed and found to be reducible passively (i.e. a type 3 ACJ injury). However, taking into account the patient’s high-level sporting activities and the high-velocity mechanism of this bipolar injury, we decided to stabilize the ACJ at the same time. There is no consensus about how a bipolar clavicle dislocation should be treated. Some studies report treating this nonsurgically,16,17,24 whereas others recommend surgical stabilization.31,32,33 Sanders et al. reported six patients with bipolar injury, all of whom he treated non-operatively.3 Four out of the six patients in his series required surgical stabilization for persistent symptoms.3 We would recomemd that, for a floating clavicle with an anterior SCJ dislocation, a LockDown stabilization of the SCJ is carried out at the medial end of the clavicle around the first rib34 together with a LockDown stabilization of the ACJ.

The polyester surgical mesh device (LockDown™) has been used with good success in acromioclavicular joint stabilization. This synthetic stabilizer has a braided weave structure that promotes tissue ingrowth.17,31,32 This method provides good stability but requires the specialized expertise of a surgeon who is experienced in operating in this area.

References

- 1.Porral A. Observation d’une double luxation de la clavicule droite. J Univ Hebd Med Chir Prat 1831; 2: 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockwood CA. Fractures and dislocations of the shoulder: part II. Subluxations and dislocations about the shoulder. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP. (eds). Fractures in adults 1984; Vol 1 Second edition Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott, pp. 722–985. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders JO, Lyons FA, Rockwood CA., Jr Management of dislocations of both ends of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72: 399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schemitsch LA, Schemitsch EH, McKee MD. Bipolar clavicle injury: posterior dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint with anterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint. A report of two cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: E18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlos AJ, Richards AM, Corbett SA. Stabilization of acromioclavicular joint dislocation using the ‘Surgilig’ technique. Shoulder and Elbow 2011; 3: 166–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeon IH, Dewnany G, Hartley R, Neumann L, Wallace WA. Chronic acromioclavicular separation: the medium term results of coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction using braided polyester prosthetic ligament. Injury 2007; 38: 1247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles E, Kumar V, Blacknall J, et al. A validation of the Nottingham Clavicle Score: a clavicle, acromio-clavicular joint and sterno-clavicular joint specific patient reported outcome measure. Bone Joint J 2013; 95B (Suppl 1) 1 (abstract).

- 8.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop 1987; 214: 160–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78: 593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bearn JG. Direct observation of the function of the capsule of the sternoclavicular joint in clavicular support. J Anat 1967; 101: 159–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer EE, Kuhn JE, Huston LJ, et al. Ligamentous restraints to anterior and posterior translation of the sternoclavicular joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11: 43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilot GJ, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA. Injuries to the sternoclavicular joint. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP. (eds). Fracture in adults, Sixth edition Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2006, pp. 1363–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glass ER, Thompson JD, Cole PA, Gause TM, Altman GT. Treatment of sternoclavicular joint dislocations: a systematic review of 251 dislocations in 24 case series. J Trauma 2011; 70: 1294–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper AA. Treatise on dislocations and on fractures of the joints, London: Longman, 1824. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ono K, Inagawa H, Kiyota K, Terada T, Suzuki S, Maekawa K. Posterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint with obstruction of the innominate vein: case report. J Trauma 1998; 44: 381–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Palma AF. Surgery of the shoulder, Third edition Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott, 1983, pp. 428–511. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gearen PF, Petty W. Panclavicular dislocation: report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1982; 64: 454–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis MG, Kummer FJ, Zuckerman JD. Dislocations of the sternoclavicular joint. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 2000; 59: 153–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DP, Davies A, Hoddinott HC. Posterior sternoclavicular dislocations – a diagnosis easily missed. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1999; 81: 201–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald PB, Lapointe P. Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. Orthop Clin N Am 2008; 39: 535–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobbs DW. Sternoclavicular joint: a new axial radiographic view. Radiology 1968; 90: 801–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinig CF. Retrosternal dislocation of the clavicle: early recognition, X ray diagnosis and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1968; 50: 830–830. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rockwood CA, Green DP. Fractures, Second edition Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heckman JD, Bucholz RW. Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults, Fifth edition Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, pp. 1264–1264. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemos MJ, Tolo ET. Complications of the treatment of the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries, including instability. Clin Sports Med 2003; 22: 371–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noda M, Shiraishi H, Mizuno K. Chronic posterior sternoclavicular dislocation causing compression of a subclavian artery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1997; 6: 564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper GJ, Stubbs D, Waller DA, Wilkinson GA, Saleh M. Posterior sternoclavicular dislocation: a novel method of external fixation. Injury 1992; 23: 565–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abiddin Z, Sinopidis C, Grocock CJ, et al. Suture anchors for treatment of sternoclavicular joint instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006; 15: 315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstrong AL, Dias JJ. Reconstruction for instability of the sternoclavicular joint using the tendon of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90: 610–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas DP, Williams PR, Hoddinott HC. A ‘safe’ surgical technique for stabilization of the sternoclavicular joint: a cadaveric and clinical study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2000; 82: 432–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wood TA, Rosell PA, Clasper JC. Preliminary results of the ‘Surgilig' synthetic ligament in the management of chronic acromioclavicular joint disruption. JR Army Med Corps 2009; 155: 191–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Echo BS, Donati RB, Powell CE. Bipolar clavicular dislocation treated surgically. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 70: 1251–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arenas AJ, Pampliega T, Iglesias J. Surgical management of bipolar clavicular dislocation. Acta Orthop Belg 1993; 59: 202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thyagarajan D, Kocsis G and Wallace WA. Unpublished data, 2014.