Abstract

Background

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes following surgical repair of the rotator cuff with emphasis upon length of immobilisation and timing of introduction of load.

Methods

An electronic search of CENTRAL, MEDLINE and PEDro was undertaken to August 2014 and supplemented by hand searching. Randomised controlled trials were included, quality appraised using the PEDro scale and synthesised via meta-analysis or narrative synthesis, based upon levels of evidence, where appropriate.

Results

Twelve studies were included. There is strong evidence that early initiation of rehabilitation does not adversely affect clinical outcome but there is a marginally higher, statistically non-significant, incidence of tendon re-tear (OR 1.3; 95% CI 0.72 to 2.2). There is strong evidence that initiation of functional loading early in the rehabilitation programme does not adversely affect clinical outcome.

Discussion

Concern about early initiation of rehabilitation and introduction of gradual functional load does not appear warranted but this should be considered in a context of potential for Type II error. There is further need to evaluate approaches that foster early initiation of rehabilitation and gradual introduction of functional load as well as considering key outcomes such as return to work.

Keywords: Physiotherapy, rehabilitation, rotator cuff, surgery, systematic review

Introduction

Shoulder pain is a highly prevalent complaint and disorders of the rotator cuff are considered to be the most common cause.1 Typically, such disorders would initially be treated using conservative means, including physiotherapy but, if nonresponsive, then surgery may be considered.2 There is evidence to suggest that the incidence of surgery to repair the rotator cuff is rising.3

Surgical techniques to repair the rotator cuff have progressed over time. With the development of arthroscopic techniques, cuff repair has become less invasive, raising the possibility of more rapid patient recovery. Evolution of suture anchors and suture configurations have also resulted in more secure repairs.4 Additionally, there has been a plethora of research relating to the effectiveness of surgical repair.5 Despite all this, our understanding of the optimal approach to post-operative rehabilitation, a critical component of the recovery process, is not well developed.4 Rehabilitation programmes have remained largely similar to those initially developed when surgical techniques were less robust.4 Uncertainty currently appears to exist around two related parameters: (i) the period of post-surgical immobilization and (ii) the amount of early load permitted at the repair site.2 In the context of this uncertainty, a generally cautious approach to post-surgical rehabilitation appears to prevail, including long periods of immobilization and the avoidance of active rehabilitation, largely as a result of an apparent fear of contributing to failure or re-tear of the repair site. This is despite good clinical outcomes reported in the presence of re-tear,6,7 which, for some, raises questions about the mechanism of action of the surgery. Indeed, excessive immobilization not only has the potential to cause stiffness and delayed functional recovery, but also might be detrimental to tendon healing. Improved clinical outcomes have been reported in other areas with early mobilization.8

Hence, the aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the effectiveness of rotator cuff repair rehabilitation programmes with a view to informing current clinical practice and also to develop a platform upon which future useful research might be conducted.

Methods

This systematic review was carried out using a predetermined protocol (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014013215) in accordance with the PRISMA statement.9

Data sources and search strategy

An electronic search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and PEDro was undertaken from their inception to August 2014. The Cochrane highly sensitive search for identifying randomized trials was adopted.10 The search terms used for the MEDLINE search are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

MEDLINE search strategy.

| Search term | Limited to: | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rotator cuff repair | Title & Abstract |

| 2 | Exercis$ or physiotherap$ or physical therap$ or rehabil$ | Title & Abstract |

| 3 | Randomized controlled$ or randomized controlled$ or controlled clinical trial or randomized or placebo or randomly or trial or groups | |

| 9 | 1 and 2 and 3 |

The electronic search was complemented by hand searching the reference lists of the articles found and previous systematic reviews. This process was undertaken by one reviewer.

Study selection

Studies had to meet the following criteria to be included:

Participants

Adult (>18 years) patients who had undergone surgical repair of the rotator cuff.

Interventions

Any post-operative rehabilitation programme.

Outcomes

Any patient-reported outcome of pain and disability.

Study design

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Language

English language.

Data extraction

One reviewer extracted data in relation to study characteristics, participant characteristics, interventions and results.

Quality appraisal

Included studies were appraised for quality using the PEDro scale.11,12 The PEDro scale was developed to facilitate appraisal of clinical trials in terms of internal validity and also the extent to which the statistical information provided makes their results interpretable.11 The 11-item scale has been widely adopted for use in systematic reviews. The domains of the scale are detailed in Table 2 where items 2 to 9 refer to the internal validity of a paper, and items 10 and 11 refer to the statistical analysis, ensuring sufficient data to enable appropriate interpretation of the results. Item 1 is related to the external validity and therefore not included in the total PEDro score.13

Table 2.

Completed PEDro quality appraisal.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arndt et al.16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Cuff & Pupello17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 4 |

| Duzgun et al.18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Hayes et al.25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Keener et al.19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Kim et al.20 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Klintberg et al.8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| Koh et al.21 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 |

| Lastayo et al.22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Lee et al.23 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Raab et al.24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 5 |

| Roddey et al.33 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 |

1, Eligibility criteria were specified. 2, Subjects were randomly allocated to groups. 3, Allocation was concealed. 4, Groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators. 5, There was blinding of all subjects. 6, There was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy. 7, There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome. 8, Measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups. 9, All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case data for at least one key outcome was analyzed by ‘intention-to-treat’. 10, The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome. 11, The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome). ✓ = criteria met; ✗ = criteria not met.

All included articles were already scored within the PEDro database, and these data were extracted from the PEDro website with studies scoring ≥6 out of 10 considered to be high quality.14

Data synthesis

As a result of the heterogeneity with regard to the patient-reported outcomes, a narrative synthesis using a rating system for levels of evidence was used.15 This rating system, displayed in Table 3, is used to summarize the results in which the quality and outcomes of individual studies are taken into account.

Table 3.

Levels of evidence.

| Strong evidence | Consistent findings in multiple high quality RCTs (n > 2) |

| Moderate evidence | Consistent findings among multiple lower quality RCTs and/or one higher quality RCT |

| Limited evidence | Only one relevant low quality RCT |

| Conflicting evidence | Inconsistent findings amongst multiple RCTs |

| No evidence from trials | No RCTs |

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

To evaluate the effect of early versus delayed rehabilitation programmes in terms of recurrent rotator cuff tendon re-tear, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The data were pooled using a random effects model via OpenMetaAnalyst software (http://www.cebm.brown.edu/open_meta). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic with p < 0.05 taken to indicate statistical heterogeneity that would preclude data pooling.

Results

Study selection

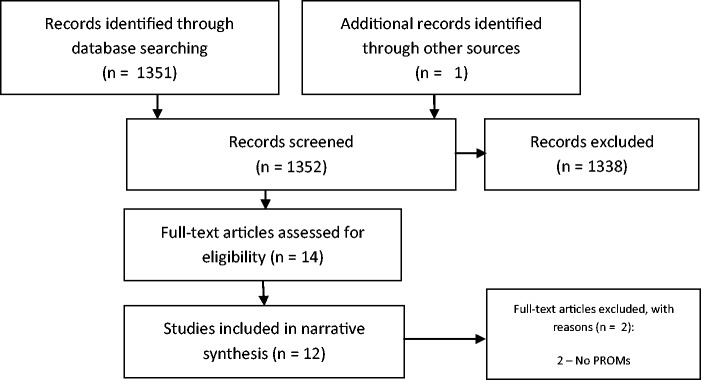

Figure 1 depicts the study selection process. The electronic search yielded a total of 1351 records. One additional source was retrieved through hand searching. The title and abstracts of 1352 articles were screened, with 14 potentially relevant studies identified for full-text review. Of these 14, two did not report patient-reported outcomes of pain and disability, leaving a total of 12 studies for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

Quality appraisal assessment

The results of the quality appraisal assessment are shown in Table 2. Four of 12 (33%) studies were regarded as high-quality clinical trials.

Study characteristics

A summary of the characteristics of the 12 included studies (819 patients; mean age 58.1 years) along with the main results is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies along with main results.

| Study characteristics | Participant characteristics | Interventions | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arndt et al.16 RCT comparing early versus delayed initiation of passive ROM followed by formal physiotherapy Conducted in France | 92 patients (mean age = 55.3 years/37% male) Main inclusion criteria: (a) Nonretracted, isolated tear of supraspinatus repaired arthroscopically | 100 patients randomized and 92 patients followed-up (1) n = 49; early ROM, commencing day 2 post-operatively, including passive ROM, CPM without ROM limitation and daily pendular exercises (2) n = 43; maintenance of sling immobilization for 6 weeks before commencement of formal physiotherapy but still undertook daily pendular exercises | Main outcomes assessed using Constant score at 12 months: Statistically significant difference of 7.9 points (p = 0.045) in favour of early group. This difference is not regarded as clinically important No statistically significant differences between groups in terms of re-tear rate (11/49 versus 7/43; p = 0.5) |

| Cuff & Pupello17 RCT comparing early versus delayed initiation of passive ROM followed by formal physiotherapy Conducted in USA | 68 patients (mean age = 63.2 years/58% male) Main inclusion criteria: (a) Isolated full-thickness tear of supraspinatus repaired arthroscopically | (1) n = 33; early ROM, commencing day 2 post-operatively, including passive elevation and external rotation directed by a PT × 3/week and supplemented by patient directed pendular exercises between formal sessions (2) n = 35; maintenance of shoulder immobilizer for 6 weeks before commencement of formal physiotherapy but still undertook daily pendular exercises | Main outcomes assessed using American Shoulder & Elbow score at 12 months: No statistically significant differences between groups including re-tear rate (5/33 versus 3/35; p > 0.05) |

| Duzgun et al.18 RCT comparing an accelerated rehabilitation programme versus a delayed programme Conducted in Turkey | 29 patients (mean age = 56.3 years/10% male) Main inclusion criteria: (a) Rotator cuff rupture repaired arthroscopically | (1) n = 13; early passive ROM, commencing day 7 post-operatively, followed by active ROM commencing day 21 and resistance from day 28. (2) n = 16; delayed programme with active ROM commencing day 42 post-operatively | Main outcomes assessed using: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder & Hand at 8 weeks, 12 weeks, 16 weeks and 24 weeks: Statistical (p < 0.05) and clinically (>10 points) significant difference in favour of the accelerated group at 8 weeks, 12 weeks and 16 weeks but no significant difference by 24 weeks |

| Hayes et al.25 RCT comparing a standardized home exercise programme plus individualized treatment versus a standardized home exercise programme alone Conducted in Australia | 58 patients (mean age = 60.2 years/71% male) Main inclusion criteria: (a) Diagnosis of rotator cuff rupture, of any size repaired surgically | (1) n = 26; sling immobilization for 1 day post-operatively followed by encouragement to commence light functional activity and pendular exercises for further 7 days. Active-assisted ROM from day 8 onwards and active and resisted exercise commenced from day 42 onwards. Supplemented by individualized physiotherapy from second week post-operatively including exercise, MT, ET at the discretion of the treating physiotherapist (2) n = 32; standardized home exercise programme alone | Main outcomes assessed using Shoulder service questionnaire (SSQ) at 6, 12 and 24 weeks: No statistically significant differences between groups across all time points except physical symptoms, lifestyle and overall shoulder status domains of SSQ at 24 weeks in favour of home exercise plus individualized treatment group. Clinical importance of this difference is unclear |

| Keener et al.19 RCT comparing early passive ROM versus delayed ROM with sling immobilization for 6 weeks Conducted in USA | 124 patients (mean age = 55.3 years/59% male) Main inclusion criteria: (a) <65 years of age (b) Diagnosis of full thickness rotator cuff tear <30 mm repaired arthroscopically | 1. n = 65; pendular exercises immediately post-operatively and therapist supervised passive ROM from 7 days post-operatively. Active ROM initiated from day 42 onwards 2. n = 59; shoulder immobilized for 6 weeks post-operatively before commencement of therapist supervised passive ROM | Main outcomes assessed using American Shoulder & Elbow score at 6 months, 12 months and 24 months: No statistically significant differences between groups including re-tear rate (6/63 versus 3/53; p = 0.46) |

| Kim et al.20 RCT comparing early passive ROM versus delayed ROM with brace immobilization for 5 weeks Conducted in South Korea | 105 patients (mean age = 60 years/42% male Main inclusion criteria: (a) Diagnosis of small to medium-sized full-thickness rotator cuff tears repaired arthroscopically | (1) n = 56; abduction brace for up to 35 days post-operatively supplemented by passive ROM 3 to 4 times per day during this period (2) n = 49; abduction brace only with no passive motion during this period | Main outcomes assessed using American Shoulder & Elbow score at 6 months and 12 months: No statistically significant differences between groups including re-tear rate (7/56 versus 9/49; p = 0.43) |

| Klintberg et al.8 RCT comparing early loading versus delayed loading Conducted in Sweden | 14 patients (mean age = 55 years/64% male) Main inclusion criteria: (a) Diagnosis of full-thickness tear repaired surgically | (1) n = 7; low-level active ROM × 3/day from day 2 post-operatively supplemented by passive ROM directed by the physiotherapist. Load was progressed from day 28 post-operatively when sling immobilization was ceased. (2) n = 7; 6 weeks of sling immobilization supplemented by passive ROM | Main outcomes assessed using Constant score at 6, 12 and 24 months: Between group difference inadequately reported; reported as no difference in adverse effects but statistical significance unclear |

| Koh et al.21 RCT comparing immobilization for four versus eight weeks Conducted in South Korea | 100 patients (mean age 59.9 years/50% male) (a) Diagnosis of full-thickness tear, 2 cm to 4 cm in size, repaired arthroscopically | (1) n = 47; 4 weeks of immobilization without passive ROM (2) n = 53; 8 weeks of immobilization without passive ROM | Main outcomes assessed using Constant score and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score at 6 months and 24 months: No statistically significant differences between groups including re-tear rate (5/40 versus 4/48; p = 0.73) |

| Lastayo et al.22 RCT comparing continuous passive motion versus manual passive ROM exercises Conducted in USA | 31 patients (mean age 63.3 years/44% male) (a) Rotator cuff tear repaired surgically | (1) n = 17; home continuous passive motion for 4 hours per day after discharge from hospital for 4 weeks, supplemented by daily pendular exercises (2) n = 15; manual passive ROM exercises three times per day performed by carer or similar for 4 weeks supplemented by daily pendular exercises | Main outcomes assessed using Shoulder Pain and Disability Index at unclear time point: No statistically significant (p > 0.05) differences between groups |

| Lee et al.23 RCT comparing aggressive versus limited passive exercises Conducted in South Korea | 64 shoulders (mean age 54.9 years/64% male) (a) Diagnosis of medium- or large-sized full-thickness rotator cuff tear repaired arthroscopically | (1) n = 30; immediate passive ROM × 2/day without limit on ROM supplemented by daily pendular exercises with shoulder brace maintained in situ for 6 weeks (2) n = 34; continuous passive movement limited to 90° × 2/day and passive ROM with shoulder brace maintained in situ for 6 weeks | Main outcomes assessed using University of California Los Angeles shoulder rating scale at 3 months and 6 months: Statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference in favour of aggressive exercise at 3 months but unknown if difference of 2.9 points is clinically significant. No statistically significant difference by 6 months (p = 0.16). No statistically significant difference between groups in terms of re-tear rate (7/30 versus 3/34; p = 0.11) |

| Raab et al.24 RCT comparing physiotherapy versus physiotherapy with continuous passive motion Conducted in USA | 26 patients (mean age 55.8 years/69% male) (a) Rotator cuff tear repaired surgically | (1) n = 12; physiotherapy (no further description) (2) n = 14; physiotherapy with continuous passive movement commencing in the recovery room, progressed within pain-free limits, and continuing for 8 hours/day for 3 weeks limited to 90° × 2/day and passive ROM with shoulder brace maintained in situ for 6 weeks | Main outcomes assessed using an author generated patient-reported shoulder score at 3 months: No statistically significant difference between groups (p = not reported) |

| Roddey et al.33 RCT comparing two approaches to home exercise instruction Conducted in USA | 108 patients (mean age 58 years/64% male) (a) Diagnosis of full-thickness tear repaired arthroscopically | (1) n = 54; videotape based home exercise instruction while sling remained in situ for 6 weeks. Passive exercise for 4 weeks to 6 weeks, followed by active exercise between 6 weeks and 12 weeks and then strengthening exercises >3 months (2) n = 54; personal PT instruction while sling remained in situ for 6 weeks. Principles of exercise progression as group 1 | Main outcomes assessed using Shoulder Pain & Disability Index at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months: No statistically significant difference between groups (p = 0.17, 0.40, 0.99 respectively) |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROM, range of motion; PT, physiotherapist/physical therapist; MT, manual therapy; ET, electrotherapy including heat and ice.

Interventions

Seven of 12 studies8,16–21 evaluated early versus delayed initiation of rehabilitation. Typically, this referred to initiation of passive range of movement (ROM), with the exception of Klintberg et al.8 who commenced low-level active ROM from day two post-operatively. There is strong evidence (consistent findings in multiple high quality RCTs) that early initiation of rehabilitation does not adversely affect outcome in terms of patient-reported outcome of pain and disability in the short (3 months), mid (6 months) or long term (≥12 months).

There is limited evidence (only one relevant low quality RCT) that early initiation of rehabilitation might favourably affect outcome in terms of patient-reported outcome of pain and disability in the short term (≤4 months) [18].

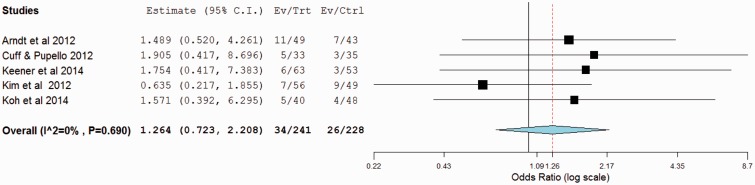

Five of 12 studies16,17,19–21 (n = 469) evaluated early versus delayed initiation of rehabilitation and reported outcomes in terms of rate of tendon re-tear. The pooled OR of tendon re-tear in the early rehabilitation group was 1.3 (95% CI 0.72 to 2.2; p = 0.41) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of odds ratios (ORs) of early versus delayed initiation of rehabilitation (OR >1 suggests higher rate of tendon re-tear in early group).

There is moderate evidence (consistent findings among multiple lower quality RCTs and/or one higher-quality RCT) that the means of initiating passive ROM (continuous passive movement, physiotherapist or patient-directed) does not affect outcome in terms of patient-reported outcome of pain and disability or rate of tendon re-tear in the short (3 months) or mid-term (6 months).22–24 Similarly, there is limited evidence (only one relevant low quality RCT) that the nature of exercise instruction; videotape or face to face, does not affect outcome in terms of patient-reported outcome of pain and disability in the short (3 months), mid (6 months) or long term (≥12 months).

There is strong evidence (consistent findings in multiple high quality RCTs) that initiation of functional loading, for example active exercise, early in the rehabilitation programme does not adversely affect outcome in terms of patient-reported outcome of pain and disability in the short (≤3 months), mid (6 months) or long term (≥12 months).8,25

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes the results of twelve studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes following surgical repair of the rotator cuff. It is suggested that concern about early initiation of rehabilitation and introduction of functional load, in the form of patient-directed active exercise, following surgical repair of the rotator cuff might not be warranted in terms of adverse patient-reported outcome. Concern surrounding tendon re-tear as an adverse outcome secondary to early initiation of rehabilitation programmes has been raised by some, although this is not supported by this current review, where a marginal increase in tendon re-tear is evident but not statistically significant.

The recommendations from this current systematic review build upon previous reviews that have highlighted the limited nature of the evidence base and suggested caution in relation to early initiation of rehabilitation and introduction of functional load.2,26–28 The strength of these current recommendations recognize the development of the evidence base in this area in terms of publication of further related RCTs. However, although we conclude that there is no evidence to delay the initiation of rehabilitation, this does not suggest that such approaches are superior to existing, delayed protocols, based upon the available data. However, in the context of the potential for superior short term outcomes, including return to work, and also the potential to reduce the early morbidity enforced through sling immobilization, further high-quality studies are indicated to enhance our understanding.

The mean age of participants within the included studies was 58 years, which suggests that a significant proportion of patients undergoing surgical repair of the rotator cuff will be engaged in gainful employment. Hence, a greater understanding of the short-, mid- and long-term implications of early initiation of rehabilitation and introduction of functional load in terms of patient-reported outcome and return to work would be useful.

The size of the initial rotator cuff tendon tear has been cited by some as a means of guiding post-operative rehabilitation where larger tears might indicate the need for a more delayed and/or relatively conservative rehabilitation protocol as a result of the integrity of the subsequent repair. However, the data presented from the included studies in this review somewhat challenge that notion. Although some studies18,25 appear to make no attempt to quantify and include all rotator cuff tears irrespective of size, some19,20 quantify the size of tear and include patients diagnosed with small- to medium-sized tears and others23 include patients diagnosed with medium- to large-sized tears. In doing so, all still report comparable outcomes between early and/or relatively aggressive rehabilitation protocols versus delayed and/or relatively conservative rehabilitation protocols. Hence, again, the data presented in this review might serve to challenge a clinical reasoning approach based upon size of the rotator cuff tear.

Following on from this point, in an attempt to offer a potential rationale for the idea that the size of the initial rotator cuff tear might not be a useful basis upon which to guide rehabilitation prescription, it is apparent that good patient-reported outcomes can still be acheived in the presence of re-tear.6,7 Thus, it is plausible that the primary mechanism of action of the surgery is not wholly biomechanical in terms of structural repair but might be impacting in some other, currently unknown, way. So, whether the tendon re-tears or not might not actually be the important factor and probably should not be the primary concern of the patient or clinician.

One outcome not considered in this review is post-operative stiffness which has been one of the suggested advantages of early versus delayed mobilization. Typically, stiffness would be quantified in terms of shoulder ROM. However, because of concerns about the level of reliability of ROM measurement and also concerns about validity29 (i.e. apparent stiffness or loss of ROM not reflecting patient report of disability), this outcome was omitted in preference for patient-reported measures of pain and disability, refecting the wider movement in outcome measurement, and re-tear rate. The former is an outcome important to the patient and the latter is an outcome that appears to be important to many clinicians, particularly surgeons.

Implications for clinical practice and further research

From a clinical perspective, this review challenges the belief that a period of enforced immobilization and unloading is necessary to achieve a good outcome following surgical repair of the rotator cuff. However, development of the evidence base is indicated in terms of the need to evaluate both short- and long-term outcomes of approaches to rehabilitation that foster early initiation of rehabilitation and gradual introduction of functional load. Important outcomes include validated measures of patient-reported outcome, for example the Oxford Shoulder Score and Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder & Hand, as well as return to work outcomes and associated economic data.

Limitations

The twelve RCTs included in this systematic review comprised an average of 68 participants. Hence, one potential caveat to consider alongside the recommendations from this review is the potential for type 2 error. Although the findings are reasonably consistent across studies the relatively small mean number of included participants per trial might indicate that any true differences between interventions could have been missed.

For pragmatic reasons, one reviewer identified relevant studies, extracted data and synthesized the findings. This approach somewhat challenges traditional systematic review guidance where it is frequently suggested that multiple reviewers should be involved at each stage.30 However, it is interesting to note that there is movement in the field of systematic review methodology towards an appreciation of rapid reviews.31 Frequently, such reviews use one reviewer at the various stages for pragmatic reasons and, although it is recognized that the potential for error might be higher, it is generally suggested that most errors or omissions do not lead to substantial changes in any conclusion32 at the same time as delivering in a timely manner.

Conclusions

Concern about early initiation of rehabilitation and introduction of gradual functional load, in the form of patient-directed active exercise, following surgical repair of the rotator cuff might not be warranted in terms of adverse patient-reported outcome or tendon re-tear. Although the evidence base relating to rehabilitation of the rotator cuff following surgical repair has developed, these conclusions are offered with the caveat of the potential for type 2 error and hence there is further need to evaluate approaches that foster early initiation of rehabilitation and gradual introduction of functional load both in the short and long term using high-quality, adequately powered, trials.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Littlewood C, May S, Walters S. Epidemiology of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review. Shoulder Elbow 2013; 5: 256–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang T, Wang S, Lin J. Comparison of aggressive and traditional postoperative rehabilitation protocol after rotator cuff repair. J Nov Physiother 2013; 3: 170–170. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ensor K, Kwon Y, DiBeneditto R, Zuckerman J, Rokito A. The rising incidence of rotator cuff repairs. J Shoulder Elb Surg 2013; 22: 1628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funk L. Arthroscopic shoulder surgery has progressed, has the rehabilitation? Int Musculoskelet Med 2012; 34: 141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr A, Rees J, Ramsay C, et al. Protocol for the United Kingdom Rotator Cuff Study (UKUFF). Bone Joint Res 2014; 3: 155–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartl C, Kouloumentas P, Holzapfel K, et al. Long-term outcome and structural integrity following open repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Int J Shoulder Surg 2012; 6: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nich C, Mutschler C, Vandenbussche E, Algereau B. Long-term clinical and MRI results of open repair of the supraspinatus tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 2613–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klintberg I, Gunarsson A, Svantesson U, Styf J, Karlsson J. Early loading in physiotherapy treatment after full-thickness rotator cuff repair: a prospective randomized pilot-study with a two-year follow-up. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 622–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther 2009; 89: 873–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Searching for studies. In: Higgins J, Green S. (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008, pp. 95–150. [Google Scholar]

- 11.PEDro. Physiotherapy Evidence Database (August 2014). http://www.pedro.org.au.

- 12.Verhagen A, de Vet H, de Bie R, et al. The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherrington C, Herbert R, Maher C, Moseley A. PEDro. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man Ther 2000; 5: 223–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moseley A, Herbert R, Sherrington C, Maher C. Evidence for physiotherapy practice: a survey of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Aust J Physiother 2002; 48: 43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.M van T, Furlan D, Bombardier C, Bouter L. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003; 28: 1290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arndt J, Clavert P, Mielcarek P, et al. Immediate passive motion versus immobilization after endoscopic supraspinatus tendon repair: a prospective randomized study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012; 98: S131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Prospective randomized study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using an early versus delayed postoperative physical therapy protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21: 1450–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duzgun I, Baltaci G, Atay A. Comparison of slow and accelerated rehabilitation protocol after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: pain and functional activity. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2011; 45: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keener J, Galatz L, Stobbs-Cucchi G, Patton R, Yamaguchi K. Rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg 2014; 96: 11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y, Chung S, Kim J, Ok J, Park I, Han J. Is early passive motion exercise necessary after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh K, Lim T, Shon M, Park Y, Lee S, Yoo J. Effect of immobilization without passive exercise after rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg 2014; 96: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lastayo PC, Wright T, Jaffe R, Hartzel J. Continuous passive motion after repair of the rotator cuff. A prospective outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 1998; 80: 1002–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee B, Cho N, Rhee Y. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy 2012; 28: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raab MG, Rzeszutko D, O’Connor W, Greatting MD. Early results of continuous passive motion after rotator cuff repair: a prospective, randomized, blinded, controlled study. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1996; 25: 214–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes K, Ginn KA, Walton JR, Szomor ZL, Murrell GAC. A randomised clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of physiotherapy after rotator cuff repair. Aust J Physiother 2004; 50: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumgarten K, Vidal A, Wright R. Rotator Cuff Repair Rehabilitation: a level I and II systematic review. Sports Health 2009; 1: 125–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Meijden O, Westgard P, Chandler Z, Gaskill T, Kokmeyer D, Millett P. Rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair; current concepts review and evidence-based guidelines. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2012; 7: 197–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang K, Hung C, Han D, Chen W, Wang T, Chien K. Early versus delayed passive range of motion exercise for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med 2014; Aug 20. pii: 0363546514544698. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.May S, Chance-Larsen K, Littlewood C, Lomas D, Saad M. Reliability of physical examination tests used in the assessment of patients with shoulder problems: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2010; 96: 179–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care 2009; Vol. 3 York: CRD, University of York. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evoluation of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 10–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones A, Remmington T, Williamson P, Ashby D, Smyth R. High prevalence but low impact of data extraction and reporting errors were found in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005; 58: 741–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roddey TS, Olson SL, Gartsman GM, Hanten WP, Cook KF. A randomized controlled trial comparing 2 instructional approaches to home exercise instruction following arthroscopic full-thickness rotator cuff repair surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2002; 32: 548–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]