Abstract

Background

Rotator cuff disorders, including rotator cuff tears, are common and can be treated conservatively or surgically. Data suggest that the incidence of surgery to repair the rotator cuff is rising. Despite this rise, the most effective approach to postoperative rehabilitation, a critical component of the recovery process, is not well developed. The present study aimed to describe current practice in the UK in relation to rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair.

Methods

An electronic survey was developed and disseminated to UK based physiotherapists and surgeons involved with rotator cuff repair.

Results

One hundred valid responses were received. Although there is a degree of variation, current practice for the majority of respondents consists of sling immobilization for 4 weeks to 6 weeks. During this time, passive movement would be commenced before active movement is introduced towards the end of this phase. Resisted exercise begins 7 weeks to 12 weeks postoperatively, alongside return to light work. A progressive resumption of function, including manual work and sport, is advised from approximately 13 weeks.

Conclusions

In the context of the current literature, it might be suggested that the current approach to rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair for the majority of respondents is somewhat cautious and has not progressed for over a decade.

Keywords: Rehabilitation, rotator cuff, physiotherapy, surgery, survey

Introduction

Shoulder pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal symptoms1 and disorders relating to the rotator cuff are considered to be the most common cause.2 Rotator cuff disorders, including rotator cuff tears, can be treated conservatively or surgically.3 Typically, surgical repair might be considered for patients with persistent shoulder pain and dysfunction who have not responded to conservative care, including physiotherapy. Data suggest that the incidence of surgery to repair the rotator cuff is rising.4

Despite the rising incidence of surgery to repair the rotator cuff, understanding of the most effective approach to postoperative rehabilitation, a critical component of the recovery process, is not well developed.5,6 Uncertainty around the timing and extent of load permitted at the repair site is apparent; some advocate early mobilization and others advocate prolonged immobilization (>1 month).5,6 Furthermore, there are those that advocate introducing load early (e.g. active exercise) versus those who only recommend passive movement.5,6

There is limited information available relating to current rehabilitation practice following rotator cuff repair. Hence, the present study aimed to describe current practice as a pre-cursor to informing and developing a future programme of research.

Materials and methods

The protocol was independently scientifically reviewed and subsequently approved by the School of Health & Related Research (University of Sheffield) research ethics committee (Ref: 001841).

Data collection

An online survey was developed by the authors and hosted by SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com) (Appendix 1) to capture pertinent information relating to the period of immobilization following surgery and the timing of the introduction of load.

The draft version of the survey was piloted by two clinicians (one physiotherapist and one surgeon) and minor modifications made in response to their feedback (i.e. clarity in the case report and stratification of response times).

As a basis upon which to answer the questions, a brief case report was presented at the outset of the survey. This vignette is based upon the typical inclusion criteria of previously published literature6 and also clinical feedback, as follows:

‘A 58-year old male has undergone an arthroscopic repair of a full thickness rotator cuff tear (2 cm). The repair is regarded as stable. He is otherwise medically well and no complications are reported.’

An invitation to complete the survey and link/contact details of the lead author were posted on the interactive Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (iCSP) website (http://www.csp.org.uk), as well as being provided via Twitter, Facebook and e-mail (Appendix 2) using the professional networks available to the researchers. The link remained live for 1 month from 13 October 2014; this was largely for pragmatic reasons relating to deadlines for further grant applications but also reflects previously published surveys where most responses occur early following posting.7

The only inclusion criteria were that respondents should be based in the UK and should be a physiotherapist or surgeon involved with rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive summary statistics were generated by SurveyMonkey and subsequently imported into Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, CA, USA) to facilitate reporting of the data.

We opted to remove responses from the same organizations where identical data was presented to minimize the potential for double-counting and hence over representation. However, where different data from the same organization was supplied then these responses were maintained. We considerd that this approach would reflect not only differences between organizations at large, but also differences between the approaches of individual surgeons within the same organization.

Results

A total of 122 surveys were completed. Following removal of non-UK and duplicate responses, 100 completed surveys remained; 93 were completed by physiotherapists and seven were by surgeons across the public and private sectors. The geographical spread of the respondents was widespread across the UK (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical spread of survey respondents (Reproduced from Ordnance Survey map data by permission of Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright 2013).

Are patients immobilized following surgery?

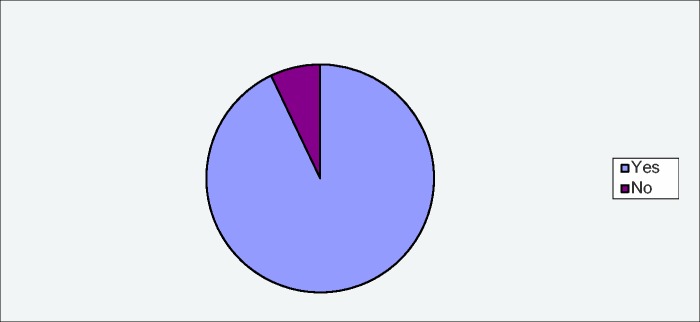

A total of 99 responses were obtained; 92 respondents (93%) indicated that patients were immobilized following surgical repair of the rotator cuff (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Are patients immobilized following surgery?

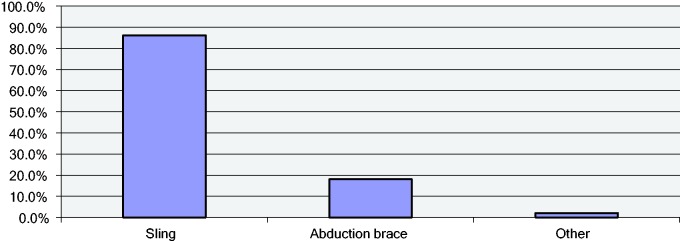

If patients are immobilized, what method of immobilization is used?

A total of 94 responses were obtained; 81 respondents (86%) indicated that a sling would be used, 17 (18%) indicated that an abduction brace would be used and two (2%) indicated that other forms of immobilization would be used but without qualification. Some respondents indicated that a sling and abduction brace would be used (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

If patients are immobilized, what method of immobilization is used?

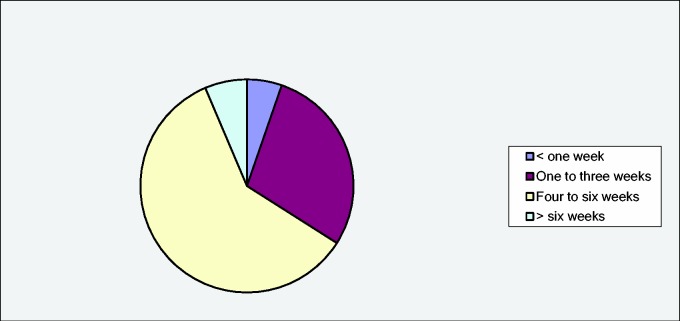

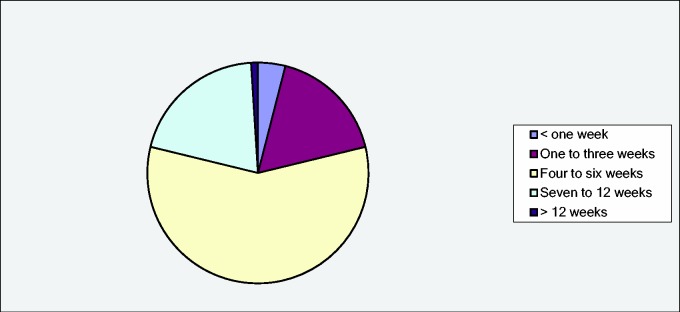

If patients are immobilized how long are they immobilized for?

A total of 94 responses were obtained; five respondents (5%) indicated that patients would be immobilized for less than 1 week, 27 (29%) indicated that patients would be immobilized for 1 week to 3 weeks, 56 (60%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks and six (6%) indicated more than 6 weeks (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

If patients are immobilized how long are they immobilized for?

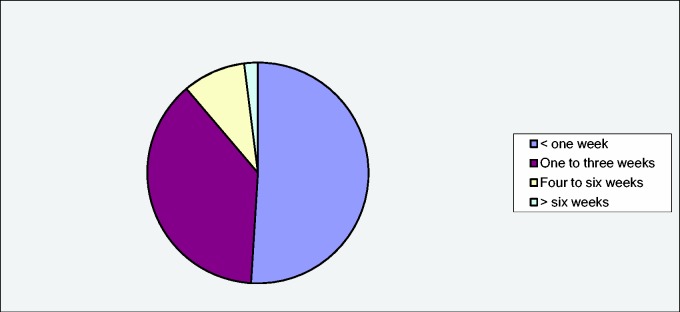

When is passive movement commenced?

A total of 98 responses were obtained; 50 respondents (51%) indicated that passive movement is commenced within the first postoperative week, 37 (38%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, nine (9%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks and two (2%) indicated more than 6 weeks (Figure 5). Typically, passive movement was performed by a combination of the physiotherapist and patient.

Figure 5.

When is passive movement commenced?

Who carries out the passive movement?

A total of 97 responses were obtained; 30 respondents (31%) indicated that the patient would carry out the passive movement, three (3%) indicated the carer, 16 (17%) indicated the physiotherapist and 48 (49%) indicated that a combination of people would undertake the passive movement.

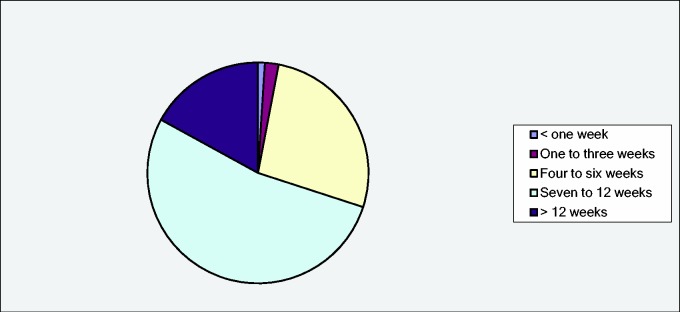

When is active movement commenced?

A total of 99 responses were obtained; four respondents (4%) indicated that active movement is commenced within the first postoperative week, 17 (17%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, 57 (58%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks, 20 (20%) indicated 7 weeks to 12 weeks and one (1%) indicated more than 12 weeks (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

When is active movement commenced?

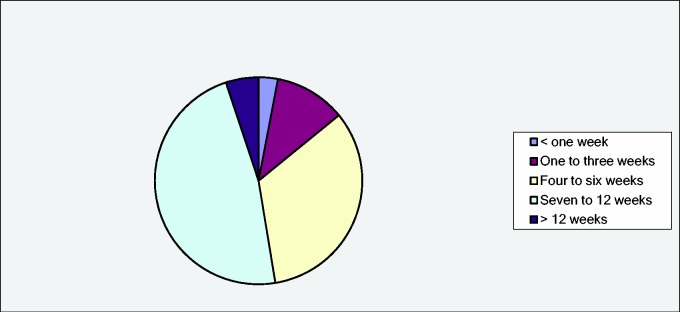

When is resisted movement commenced?

A total of 100 responses were obtained; one respondent (1%) indicated that resisted movement/exercise is commenced within the first postoperative week, two (2%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, 27 (27%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks, 53 (53%) indicated 7 weeks to 12 weeks and 17 (17%) indicated more than 12 weeks (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

When is resisted movement commenced?

When do you recommend commencement of light work (e.g. computer operation etc.)?

A total of 99 responses were obtained; three respondents (3%) indicated that light work is commenced within the first postoperative week, 11 (11%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, 33 (33%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks, 47 (48%) indicated 7 weeks to 12 weeks and five (5%) indicated more than 12 weeks (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

When do you recommend commencement of light work (e.g. computer operation, etc.)?

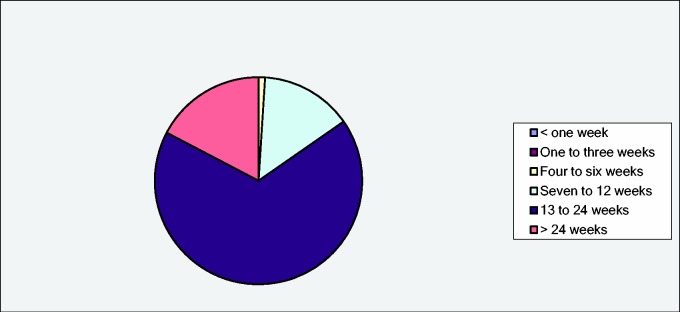

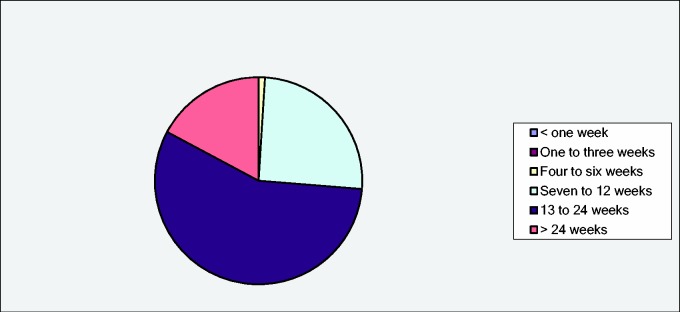

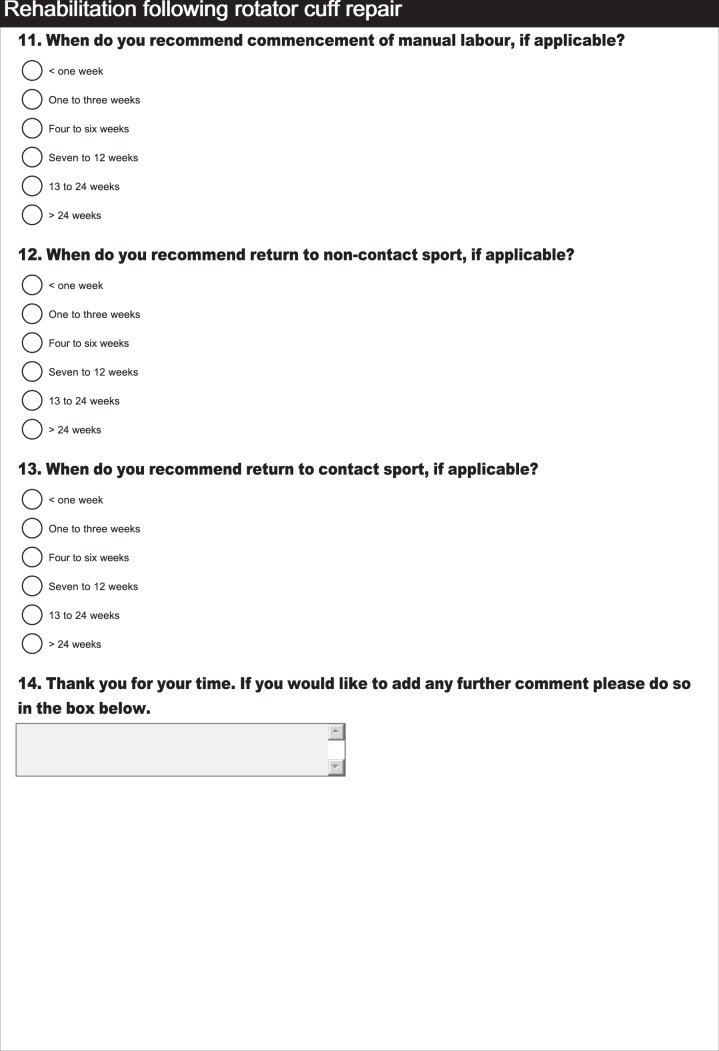

When do you recommend commencement of manual labour, if applicable?

A total of 98 responses were obtained; no respondents (0%) indicated that manual labour is commenced within the first postoperative week, none (0%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, one (1%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks, 14 (14%) indicated 7 weeks to 12 weeks, 66 (67%) indicated 13 weeks to 24 weeks and 17 (17%) indicated more than 24 weeks (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

When do you recommend commencement of manual labour, if applicable?

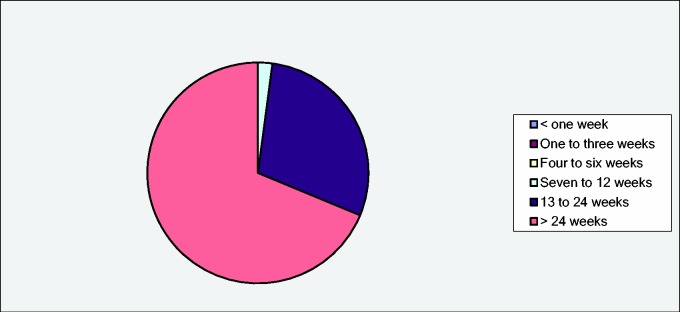

When do you recommend return to non-contact sport, if applicable?

A total of 99 responses were obtained; no respondents (0%) indicated that non-contact sport is commenced within the first postoperative week, none (0%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, one (1%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks, 25 (25%) indicated 7 weeks to 12 weeks, 56 (57%) indicated 13 weeks to 24 weeks and 17 (17%) indicated more than 24 weeks (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

When do you recommend return to non-contact sport, if applicable?

When do you recommend return to contact sport, if applicable?

A total of 96 responses were obtained; no respondents (0%) indicated that contact sport is commenced within the first postoperative week, none (0%) indicated 1 week to 3 weeks, none (0%) indicated 4 weeks to 6 weeks, two (2%) indicated 7 weeks to 12 weeks, 28 (29%) indicated 13 weeks to 24 weeks and 66 (69%) indicated more than 24 weeks (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

When do you recommend return to contact sport, if applicable?

Discussion

As might be expected, there is a degree of variation in current practice in relation to rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair. However, based upon these data, following surgical repair of the rotator cuff, most patients in the UK would currently be immobilized using a sling for 4 weeks to 6 weeks. During this time, passive movement would be commenced through a joint effort of the patient and physiotherapist. Subsequently, active movement would be commenced before resisted exercise is introduced to rehabilitation between 7 weeks to 12 weeks postoperatively, alongside return to light work. A progressive resumption of function, including manual work and sport, is advised from approximately 13 weeks for the majority.

The findings from this survey largely concur with the practice recommendations made by Cohen et al.8 in 2002 who recommended 0 weeks to 6 weeks of immobilization/passive movement only followed by active-assisted range of movement exercise between 6 weeks and 12 weeks. From week 12, commencement of resisted exercise was recommended. This confirms the suggestion made by Funk5 who raised concern that rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair has not progressed significantly over recent years. This lack of progression is despite advancement in surgical technique in terms of less invasive operations and hence less tissue damage and stronger implants resulting in more secure repairs, which should permit earlier mobilization and faster recovery.5

In the context of the current literature,5,6 the static nature of the majority approach to rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair is appropriately open to question. A recent systematic review has reported that concerns about adverse outcomes, for example negative patient-reported outcome and increased re-tear rate of the rotator cuff, secondary to more progressive approaches or early mobilization, are not supported by the current literature.6 Hence such concerns, which appear to be a direct barrier to progression, are open to challenge, although the reasons for such caution are appreciable because much of the research that has been undertaken to date has included small numbers of participants and therefore the potential for type II error exists.6

Although the majority approach characterized by this survey suggests a logical, albeit delayed, progression of loading, any opportunities to reduce the morbidity associated with prolonged immobilization and improve patient-reported outcome, including return to work, might be missed. In the context of surgical advancement and clinical uncertainty, the case for further evaluation of early but graduated programmes of patient directed rehabilitation is apparent6 with usual care, as defined by the majority approach here, as a valid comparator.

Study limitations

Although an excellent geographical spread of responses was obtained and there is a reasonable degree of concordance between responses, 100 self-selected respondents is likely to represent only a small proportion of all clinicians involved with rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair. It is apparent that the practice of some respondents varies from the majority who were approached and that a continuum of practice is likely to exist encompassing what might best be described as advocates of early to delayed mobilization.

Conclusions

In the context of contemporary literature, it might be suggested that current approaches to rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair for the majority of respondents is somewhat cautious and has not progressed over the last decade or so. Further high-quality research evaluating more progressive approaches to rehabilitation in comparison to usual care might help to address current clinical uncertainty and caution and hence progress our understanding of the optimal approaches to rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair. This survey has defined usual rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair in the UK and hence this detail could be used as the standard practice comparator in future clinical trials.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Invitation to complete survey

Are you are a physiotherapist or surgeon involved with rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair? Would you be willing to spare five minutes to help us with our research?

Despite surgical advances and an increasing number of operations being carried out to repair the rotator cuff, relatively little is known about the optimal approach to post-operative rehabilitation. Therefore, we are conducting a survey to help us better understand current practice prior to developing a clinical trial.

For further detail and access to the survey please follow this link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/DR82RTB

If you have any concerns or questions please contact us:

Chris Littlewood (c.littlewood@sheffield.ac.uk /@physiochris)

Marcus Bateman (marcus.bateman@nhs.net)

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Mitchell C, Adebajo A, Hay E, Carr A. Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ 2005; 331: 1124–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Littlewood C, May S, Walters S. Epidemiology of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review. Shoulder Elbow 2013; 5: 256–65. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang T, Wang S, Lin J. Comparison of aggressive and traditional postoperative rehabilitation protocol after rotator cuff repair. J Nov Physiother 2013; 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensor K, Kwon Y, DiBeneditto R, Zuckerman J, Rokito A. The rising incidence of rotator cuff repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22: 1628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funk L. Arthroscopic shoulder surgery has progressed, has the rehabilitation? Int Musculoskelet Med 2012; 34: 141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littlewood C, Bateman M, Clark D, et al. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Shoulder Elbow 2015; 00: 000–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Littlewood C, Lowe A, Moore J. Rotator cuff disorders: survey of current UK physiotherapy practice. Shoulder Elbow 2012; 4: 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen B, Romeo A, Bach B. Rehabilitation of the shoulder after rotator-cuff repair. Oper Tech Orthop 2002; 12: 218–24. [Google Scholar]