Abstract

Neuropathic arthropathy of the elbow is a rare condition, which is disabling and difficult to treat. Initial treatment is conservative and arthrodesis is rarely indicated. We describe an unusual case of progressive unilateral elbow swelling in a 37-year-old female domestic helper. She was found to have neuropathic arthropathy of her right elbow secondary to underlying cervico-thoracic syringomyelia. She underwent decompression of the syringomyelia before underdoing elbow fusion. Her elbow was initially immobilized in a cast to minimize bony fragmentation and soft tissue swelling. Serial X-rays were performed with a regular change of cast as the swelling subsided. When there was no further radiological evidence of bony fragmentation, elbow fusion at 60° was performed using a two-plate technique at 7 months after the initial presentation. With well-preserved ipsilateral hand function, she was could still perform household chores despite having a fused elbow. Radiological evidence of successful elbow fusion was documented at 23 weeks after surgery. There were no complications. If elbow fusion is considered, we recommend a trial of immobilization in the preferred angle of fusion to assess the patient’s suitability. Factors such as the young age of a patient and good quality bone may also contribute to the success of the fusion

Keywords: bone graft, Charcot joint, elbow arthrodesis, fusion, neuropathic arthropathy

Introduction

Neuropathic arthropathy, also known as Charcot arthropathy, is a chronic, progressive degeneration of a joint associated with an underlying neurological disorder. It is characterized by dislocations, pathological fractures, joint disorganization and destruction, which eventually leads to debilitating deformities and loss of function.1

We describe an unusual case of unilateral elbow swelling in a 37-year-old lady. She was later found to have a neuropathic elbow secondary to cervicothoracic syringomyelia related to an Arnold–Chiari malformation. She was successfully treated with elbow fusion following decompression of the syringomyelia.

We chose to highlight this case because of its rarity and lack of established treatment guidelines. To the best of our knowledge, most of the current literature comprises of case reports and small case series with limited outcome data.2–12

Case report

The patient is a 37-year-old domestic helper who was previously well. She initially presented with progressive right elbow swelling associated with numbness, parasthesiae in her forearm and mild pain in her right elbow for 3 months. There was pain on rest and on movement and she was not on prior analgesia. There was no history of fall or trauma. She denied any fever, chills, night sweats or any other constitutional symptoms.

On examination, there was uniform swelling of the right elbow. The range of motion was 0–120°, with full pronation and supination. Joint crepitus was felt on movement. Valgus instability was noted. Neurological examination revealed weakness of finger adduction and abduction, as well as sensory deficits in the right C5 to T1 dermatome.

Examination of the cervical spine and contralateral upper limb was otherwise normal.

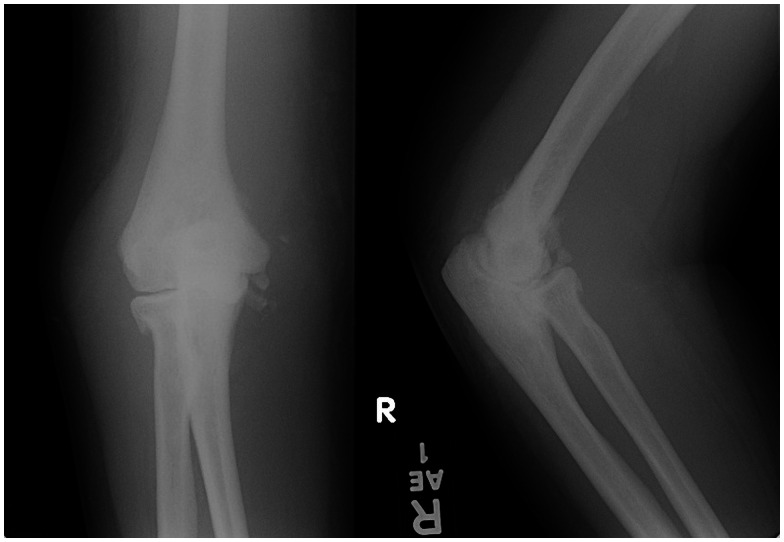

Radiographs of the right elbow showed degenerative changes with marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, joint space narrowing and an increase in radiocapitellar gap (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showing degenerative changes with marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, joint space narrowing and increase in radiocapitellar gap.

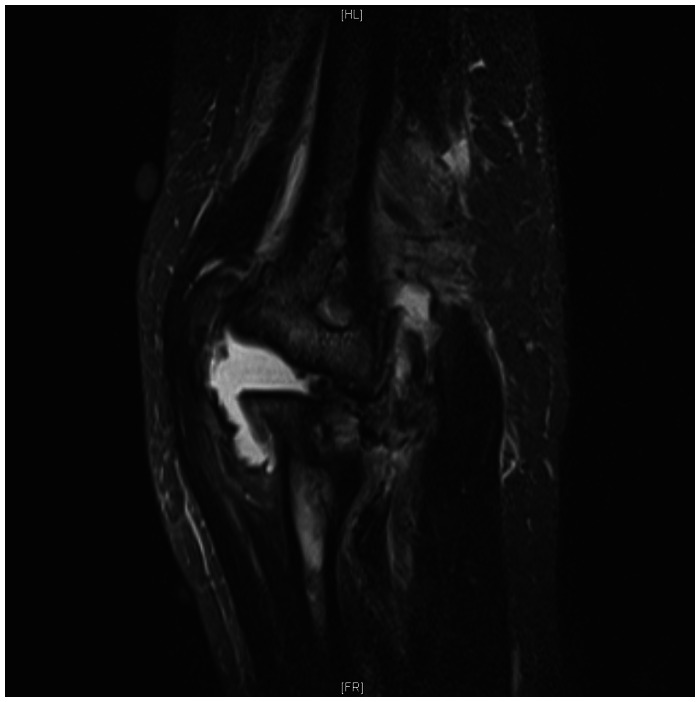

Further elbow imaging was carried out to rule out tuberculosis of the elbow and septic arthritis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the elbow showed a large joint effusion, diffuse subcutaneous swelling and oedema, joint disorganization with radiocapitellar subluxation and multiple loose bodies (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

T2 weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging of the right elbow showing large joint effusion, diffuse subcutaneous swelling and oedema, joint disorganization with radiocapitellar subluxation and loose bodies.

Figure 3.

T2 weighted saggital magnetic resonance imaging of the right elbow with similar features as in Fig. 2.

In view of a possible infective aetiology for her symptoms, her right elbow was aspirated and the fluid sent for microbiological studies. Fluid gram stain and bacterial culture, fungal smear and cultures and acid fast bacilli smear were negative. A mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction test and syphilis serology were negative as well.

In addition, a plain chest radiograph did not reveal any features suspicious of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was mildly elevated. Total white cell count, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor and serum uric acid were within normal limits.

In view of her neurological symptoms, further MRI of her spine was performed, which revealed a long segment of syrinx involving the whole cervical and thoracic spinal cord, down to T11 causing expansion of the cord down to T7 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

T2 weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine showing thoracic syringomyelia.

A neurosurgery opinion was obtained. Further MRI of the brain revealed a Chiari type 1 malformation with cerebellar tonsillar herniation (Figure 5). She subsequently underwent posterior fossa decompression and partial cerebellar tonsillectomy.

Figure 5.

T2 weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine demonstrating the extent of the cervical syrinx.

After 7 months of treatment with analgesia and elbow immobilization using a cast, the patient still complained of worsening elbow pain and instability, which affected her activities of daily living. Radiographs showed worsening bony fragmentation and bone loss.

Surgical options were discussed with her, with special attention being paid to her functional demands. She agreed to right elbow fusion at 60° of flexion because she felt that it was the most ideal position for performing household chores. During surgery, we found severe destruction of all articular surfaces with complete dislocation of the elbow. The proximal radioulnar joint was intact. Fusion was achieved using a 12-hole, 3.5 locking compression plate (LCP) (Synthes; Mathys Medical Ltd, Bettlach, Switzerland) (Figure 6) and augmented with a six-hole, 3.5 LCP (lot number 223.541–601, Synthes; Mathys Medical Ltd) (Figure 7). Viable resected bone was used as bone graft at the fusion site. The elbow was protected in a back-slab. She was discharged well 4 days after surgery.

Figure 6.

Operative photo showing position of the posterior plate.

Figure 7.

Operative photo showing position of the medial plate.

After the surgery, we continued to immobilize the patient’s elbow in a plaster cast until there was radiological evidence of ongoing union. She reported decreased elbow pain and swelling, with no further deterioration in neurological deficit. At 5 weeks after surgery, she was able to hold a cup and use a knife with her right hand. Her plaster cast was removed at 23 weeks when there was radiological evidence of fusion (Figure 8). The patient remained well 36 weeks after surgery. No further follow-up was possible because she was repatriated to her home country.

Figure 8.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiograph at 23 weeks after surgery showing successful fusion.

Discussion

Neuropathic arthropathy is a rare condition, with only a few case reports and small case series being reported in the literature.1–12 The incidence of elbow joint involvement in patients with neuropathic arthropathy is considered to range from 3% to 8%. Eichenholtz reported three cases of neuropathic elbow out of 94 joints.13

There are many known causes for neuropathic arthropathy.14 The pattern of joint involvement depends on the underlying aetiology. Diabetic patients tend to develop neuropathic joints in the distal joints of the lower limbs such as the ankle and foot. Patients with tertiary syphilis tend to develop them in the hips and knees. Patients with syringomyelia tend to develop them in the upper limbs. In a study of 12 patients with neuropathic arthropathy secondary to syringomyelia, the elbow accounted for 10 out of 16 affected joints.15

Syringomyelia is a pathological entity characterized by spinal cord cavitation that often translates into a progressive clinical syndrome ranging from minimal to significant loss of neurological function.16 It has many underlying aetiologies, although is commonly described together with an underlying Chari malformation. Chiari type 1 malformations were first described by Hans Chiari in 1891 as an elongation of the tonsils and the medial parts of the inferior lobes of the cerebellum into cone-shaped projections that accompany the medulla oblongata into the spinal canal.17 Some 40% to 65% of cases of Chiari type 1 malformation are associated with spinal cord cavitation.16 Further discussion of this rare condition is beyond the scope of the present case report. Prompt neurosurgical consultation to consider curative surgery should be obtained, as was carried out for our patient.

Although surgical management of Charcot arthropathy involving the lower limb is well described in the current literature, although the same cannot be said for that of the upper limb. Current consensus recommends conservative management, which includes analgesia, elbow immobilization, physiotherapy, and management of patient expectations, as a result of unpredictable surgical outcomes. In a 2006 review of six neuropathic elbows, all three patients who were managed surgically developed postoperative complications that required additional surgery.10 In a case of ulcerated neuropathic elbow treated with external fixation, persistent elbow instability, deformity and loss of function was reported at 21 months after surgery.3 Similar instability was reported after treating a case of septic neuropathic elbow with surgical debridement and external fixation.2 In the recent literature, there has been at least one case of successful arthrodesis in a neuropathic elbow.3,4

Choosing the most optimal treatment for our patient proved to be difficult because of a lack of clear treatment guidelines for this rare condition. The decision to proceed with elbow arthrodesis was made only after discussion with the patient and in consultation with other orthopaedic surgeons. Options considered included immobilization (with cylindrical cast or hinged elbow brace) and elbow arthrodesis. The patient had previously expressed a desire to maintain some degree of upper limb functionality and independence in activities of daily living. These were taken into account during the decision-making process.

Originally described in the treatment of tuberculous arthritis,18 elbow arthrodesis is now rarely performed.19–21 It is considered to be a salvage procedure that is highly disabling to the patient22 and is only performed when there are no other reasonable reconstructive options. It is technically challenging because of the significant forces acting across the elbow joint and associated with a high complication rate and often unacceptable functional limitations for the afflicted patient.19 Arthrodesis is mainly performed for patients with severe joint destruction as a result of post-traumatic arthrosis, instability or infection.21,23 It has been used in cases where total elbow arthoplasty has failed or is contraindicated.24 However, in several studies, successful elbow arthrodesis has been found to improve pain control and elbow function significantly.4,23

Much controversy surrounds the optimal angle of fusion for arthrodesis. A lack of large studies involving patients who have undergone elbow arthrodesis reflects the relative rarity of the procedure. Most sizable clinical studies involve healthy volunteers undergoing simulated arthrodesis.25,26 The current recommendations are for a fusion angle of 90° to 100°. A study by Tang et al. involving simulated arthrodesis in 24 volunteers showed that a fusion angle of 90° to 110° produced the best functional outcome, with poorer outcomes on either extremes of fusion angle.25 In another study by Nagy et al., 25 volunteers underwent elbow immobilization at either 45° or 90°, with 22 out of 25 preferring immobilization at 90°.26 However, despite clear patient preferences, significant functional limitations existed in both positions, and hence it was concluded that there was no optimal angle of fusion.26 We agree with the notion that there is no single perfect approach to determining the optimal fusion angle and that all patients should undergo a trial of immobilization at various angles to attain a fusion angle best suited to their functional needs.19,23,25,26

We chose to proceed with a fusion angle of 60° because it was well tolerated by the patient and satisfied her own individual functional requirements. Prior to surgery, the patient was able to tolerate elbow casting and bracing at 60°. The patient had previously expressed a desire to continue her employment as a domestic helper after elbow fusion; hence, she was satisfied with this position because she was able to perform basic household chores with relative ease. We felt that, although the previously suggested fusion angles of 90° to 100° provided optimal function for activities of daily living (ADL) and self-care, they do not necessarily represent the ideal position for a patient who prioritizes work-related activity over self-care and ADL. Retrospectively, we would have preferred to attempt a trial of elbow bracing at various angles to determine the best position for our patient. Total elbow arthoplasty was contraindicated because pf the patient’s functional requirements. She has to carry relatively heavy loads with the operated limb, increasing the risk of implant failure.

We chose to utilize viable resected bone from the elbow as a bone graft instead of conventional iliac crest bone graft for several reasons. The patient was young, otherwise healthy and had good quality bone with no concomitant infection in the elbow. We felt that it was beneficial to the patient because it would eliminate the need for a second surgical incision, at the same time as also reducing the associated pain and morbidity that accompanies harvesting bone graft from the iliac crest. We postulate that patient factors, together with the inherent stability of our double-plate construct, could have contributed to successful elbow fusion. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the literature that uses viable resected bone as bone graft for elbow fusion.

Conclusions

Neuropathic elbow is a rare and disabling condition that is challenging to diagnose and treat. This case highlights the importance of managing patient’s expectations and performing a thorough functional assessment before elbow arthrodesis because the angle of fusion depends on the patient’s individual requirements. In appropriately selected patients, good outcomes and high levels of patient satisfaction can be achieved even when a disabling and technically complicated procedure such as elbow arthrodesis is performed. Bone grafting using viable resected bone from the surgical site is an alternative to traditional iliac crest bone grafts in young patients with good bone quality.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Kelly M. De arthritide symptomatica of William Musgrave (1657–1721): his description of neuropathic arthritis. Bull Hist Med 1963; 37: 372–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unnanuntana A, Waikakul S. Neuropathic arthropathy of the elbow: a report of two cases. J Med Assoc Thai 2006; 89: 533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeap JS, Wallace AL. Syringomyelic neuropathic ulcer of the elbow: treatment with an external fixator. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 506–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaishya R, Singh AP. Arthrodesis in a neuropathic elbow after posttubercular spine syrinx. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18: e13–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deirmengian CA, Lee SG, Jupiter JB. Neuropathic arthropathy of the elbow. A report of five cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83A: 839–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farzan M, Eraghi AS, Mardookhpour S, Yousefzadeh-Fard Y. Neuropathic arthropathy of the elbow: two case reports. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012; 41: E39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruette P, Stuyck J, Debeer P. Neuropathic arthropathy of the shoulder and elbow associated with syringomyelia: a report of 3 cases. Acta Orthop Belg 2007; 73: 525–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhaskaran R, Suresh K, Iyer GV. Charcot's elbow (a case report). J Postgrad Med 1981; 27: 194–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minami A, Kato H, Hirayama T. Occurrence of neuropathic osteoarthropathy of the elbow joint after fixation of the radius nonunion in a patient with syringomyelia. J Orthop Trauma 1997; 11: 454–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon YW, Morrey BF. Neuropathic elbow arthropathy: a review of six cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006; 15: 378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nacir B, Arslan Cebeci S, Cetinkaya E, Karagoz A, Erdem HR. Neuropathic arthropathy progressing with multiple joint involvement in the upper extremity due to syringomyelia and type I Arnold-Chiari malformation. Rheumatol Int 2010; 30: 979–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanik B, Tuncer S, Seckin B. Neuropathic arthropathy caused by Arnold–Chiari malformation with syringomyelia. Rheumatol Int 2004; 24: 238–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichenholtz SN. Charcot joints, Springfield, IL: Thomas, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley JC, Collier AM. Charcot osteo-arthrpathy. Curr Orthop 2008; 22: 428–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng X, Wu L, Yang C, Xu Y. Neuropathic arthropathy caused by syringomyelia. J Neurosurg Spine 2013; 18: 303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma M, Coppa N, Sandu F. Syringomyelia: a review. Semin Spine Surg 2006; 18: 180–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koehler PJ. Chiari’s description of cerebellar ectopy (1891). With a summary of Cleland’s and Arnold’s contributions and some early observations on neural-tube defects. J Neurosurg 1991; 75: 823–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arafiles RP. A new technique of fusion for tuberculous arthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981; 63: 1396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galley IJ, Bain GI, Stanley JC, Lim YW. Arthrodesis of the elbow with two locking compression plates. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 8: 141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovack TJ, Jacob PB, Mighell MA. Elbow arthrodesis: a novel technique and review of the literature. Orthopedics 2014; 37: 313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reichel LM, Wiater BP, Friedrich J, Hanel DP. Arthrodesis of the elbow. Hand Clin 2011; 27: 179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fornalski S, Gupta R, Lee TQ. Anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow joint. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2003; 7: 168–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koller H, Kolb K, Assuncao A, Kolb W, Holz U. The fate of elbow arthrodesis: indications, techniques, and outcome in fourteen patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preiss RA, Wigderowitz CA. Vascularized fibular graft arthrodesis as salvage for severe bone loss following failed revision total elbow replacement. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2011; 21: 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang C, Roidis N, Itamura J, Vaishnau S, Shean C, Stevanovic M. The effect of simulated elbow arthrodesis on the ability to perform activities of daily living. J Hand Surg Am 2001; 26: 1146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagy SM, Szabo RM, Sharkey NA. Unilateral elbow arthrodesis: the preferred position. J South Orthop Assoc 1999; 8: 80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]