Abstract

Vascular smooth muscle contraction is primarily regulated by phosphorylation of myosin light chain. There are also modulatory pathways that control the final level of force development. We tested the hypothesis that protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase modulate vascular smooth muscle activity via effects on MAP kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1). Swine carotid arteries were mounted for isometric force recording and subjected to histamine stimulation in the presence and absence of inhibitors of PKC [bisindolylmaleimide-1 (Bis)], MAP kinase kinase (MEK) (U0126), and MKP-1 (sanguinarine) and flash frozen for measurement of MAP kinase, PKC-potentiated myosin phosphatase inhibitor 17 (CPI-17), and caldesmon phosphorylation levels. CPI-17 was phosphorylated in response to histamine and was inhibited in the presence of Bis. Caldesmon phosphorylation levels increased in response to histamine stimulation and were decreased in response to MEK inhibition but were not affected by the addition of Bis. Inhibition of PKC significantly increased p42 MAP kinase, but not p44 MAP kinase. Inhibition of MEK with U0126 inhibited both p42 and p44 MAP kinase activity. Inhibition of MKP-1 with sanguinarine blocked the Bis-dependent increase of MAP kinase activity. Sanguinarine alone increased MAP kinase activity due to its effects on MKP-1. Sanguinarine increased MKP-1 phosphorylation, which was inhibited by inhibition of MAP kinase. This suggests that MAP kinase has a negative feedback role in inhibiting MKP-1 activity. Therefore, PKC catalyzes MKP-1 phosphorylation, which is reversed by MAP kinase. Thus the fine tuning of vascular contraction is due to the concerted effort of PKC, MAP kinase, and MKP-1.

Keywords: bisindolylmaleimide-1, U0126, sanguinarine, caldesmon, CPI-17, phos-tag gel electrophoresis

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase; also known as p42/p44 MAP kinase) is a serine/threonine protein kinase that has been identified in several types of smooth muscle (7, 10, 19). MAP kinase is activated via dual phosphorylation of Thr187 and Tyr185 catalyzed by MAP kinase kinase (MEK) and has been shown to play a significant role in activating several proteins required for cell growth in proliferating dedifferentiated smooth muscle cells (24, 26). However, the role of MAP kinase in differentiated, contractile smooth muscle cells is not as well understood.

In differentiated smooth muscle, it has been suggested that MAP kinase may be involved in calcium-independent regulation of smooth muscle contraction (17). MAP kinase has been shown to phosphorylate the thin filament protein caldesmon and relieve its inhibitory action on the actin-activated myosin ATPase, thus increasing the affinity between myosin and actin and cross-bridge cycling (1, 10, 23, 11, 23, 34). Moreover, MAP kinase is thought to participate in calcium sensitization pathways of smooth muscle contraction (61). Before the development of MEK inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been utilized to study the effect of inhibition of tyrosine kinase inhibition on vascular contraction as MAP kinase activation involves tyrosine phosphorylation (60). Studies using tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been shown to have no significant effect on depolarization-induced contractions that rely on influx of extracellular calcium (8). In contrast, tyrosine kinase inhibitors induce relaxation in calcium-stimulated α-toxin-permeabilized tissues (13, 50). Thus MAP kinase may have a role in regulating smooth muscle contraction in a calcium-independent manner or by increasing the contractile filament's sensitivity to calcium.

In addition to MAP kinase, protein kinase C (PKC) is an important kinase involved in increasing the contractile filament sensitivity to calcium. PKC inhibits myosin light chain phosphatase activity by activating PKC-potentiated myosin phosphatase inhibitor 17 (CPI-17), resulting in increased levels of myosin light chain phosphorylation (47, 62). MAP kinase and its activator MEK have been shown to be activated via PKC-mediated phosphorylation in various cell types (2, 21, 37, 43). Furthermore, MAP kinase and PKC have been shown to translocate to the surface membrane upon phenylephrine-induced smooth muscle contraction (61). MAP kinase then redistributes toward the contractile filaments during prolonged stimulation in aortic cells (27). This redistribution toward the contractile filaments occurs in the absence of calcium and is prevented in the presence of PKC inhibitors (27). Therefore, MAP kinase may be a downstream substrate of PKC and participate in regulating smooth muscle contraction.

In this study, we examined the relationship of MAP kinase and PKC in an intact preparation of vascular smooth muscle to delineate a link connecting the two signaling pathways at rest and during prolonged stimulation-induced contraction. We hypothesized that, upon prolonged stimulation, PKC phosphorylates and activates MAP kinase, which will lead to the phosphorylation of caldesmon and/or alterations in force development. Ultimately, we demonstrated that the relationship between MAP kinase and PKC is more complex than originally hypothesized as MAP kinase is not regulated by PKC through direct phosphorylation, rather PKC indirectly regulates MAP kinase activity via activation of MAP kinase phosphatase 1 (MKP-1, also known as dual-specificity protein phosphatase 1), a phosphatase that dephosphorylates tyrosine, serine, and threonine residues (40, 51). MKP-1 is present in most cell types, but, important to this present study, it is expressed in arterial smooth muscle (2, 14, 15, 38). Moreover, we also show a negative feedback regulatory mechanism between MAP kinase and MKP-1 that may serve to tightly regulate MAP kinase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All reagents for solutions, unless otherwise specified, were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and were of analytic grade or better. Histamine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All electrophoretic and blotting supplies were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Vascular preparation.

Swine carotid arteries were obtained from a local slaughterhouse and transported in ice-cold physiological salt solution (PSS) containing the following (in mM): 140 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.2 Na2HPO4, 0.02 Na2-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 2.3-(N-morpholino)propane sulfonic acid (pH 7.4). The arteries were cleaned of connective tissue and excess fat and stored in PSS (as described above) containing 5 mM d-glucose at 4°C. For all experiments, strips of the medial layer, which is predominantly smooth muscle cells, were used and obtained by removal of the intimal and adventitial layers. Arteries were never stored for more than 4 days at 4°C in PSS; viability and contractility of the arteries are not changed by this storage.

Isometric force recording.

Intact medial strips of swine carotid artery were suspended between a Grass FT.03 force transducer and a stationary clip in water-jacketed organ baths. The strips were stretched to 5 g of force and allowed to stress-relax in PSS at 37°C and bubbled with 100% O2 for at least 45 min. A passive force of ∼10% of active force (∼1–1.5 g) was applied to all strips. This applied passive force sets the muscle at a length that approximates the length for the development of maximal active force. The strips were subjected to several 10-min exposures to a membrane depolarizing KCl PSS (KCl, equimolar substitution for NaCl) followed by relaxation in PSS. This contraction/relaxation cycle was continued until similar levels of maximal force production were attained. Following relaxation to baseline in PSS, the tissues were incubated with inhibitors of MEK (10 μM U0126; EMD Chemicals, Billerica, MA), PKC [3 μM bisindolylmaleimide-1 (Bis); EMD Chemicals], or MKP-1 30 μM sanguinarine (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) for 30 min. The tissues were then maximally stimulated with 10 μM histamine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min, unless noted otherwise. For immunoblots, the tissues were snap frozen using a 6% trichloroacetic acid-acetone-dry ice slurry containing 10 mM DTT. The strips were allowed to slowly thaw to room temperature, homogenized in a 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, homogenization buffer using glass-glass homogenizers and assayed for protein concentration. For immunohistochemistry, tissues were carefully placed in 10% formalin overnight and then dehydrated in 70% ethanol. The tissues were gently handled by the ends to minimize alterations in signaling mechanisms due to mechanical stress of the forceps.

Immunoblots for MAP kinase, CPI-17, MKP-1, and Ser789-caldesmon phosphorylation.

Twenty to forty micrograms of the tissue lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 100 V for 1 h and 15 min at 4°C, as previously described in detail (56, 57). Briefly, the membranes were blocked and then incubated in primary antibodies against active, phosphorylated MAP kinase (1:5,000, Promega, Madison, WI) and total p42/p44 MAP kinase (1:1,000, Millipore, Billerica, MA); Thr38-phosphorylated CPI-17 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and total CPI-17 (1:400, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Ser359-MKP-1 phosphorylation (1:1,000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and total MKP-1 (1:1,000, Abcam); or Ser789-caldesmon phosphorylation (1:1,000, Millipore) and total caldesmon (1:5,000, Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4°C. The membranes probed with the above antibodies, except phosphorylated and total MKP-1, were washed followed by incubation in anti-mouse 800cw and anti-rabbit 680 fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:10,000; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) for 45 min at room temperature. The washes were repeated, and the membranes were imaged and quantified using an Odyssey Infrared Imager and Odyssey analysis software. Phosphorylated MKP-1 blots were washed and incubated in mouse anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). The blots were stripped, reprobed using the total MKP-1 antibody listed above, and then incubated in donkey-anti-goat IgG-horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). Membranes were visualized using Forte ECL (Millipore), imaged with a FluorChem M FM0501 imager, and quantified using ImageJ software.

Phos-tag SDS-PAGE for total caldesmon phosphorylation.

Samples were loaded onto a 2.7% polyacrylamide separating gel containing 100 μM Phos-tag, 100 μM MnCl2, and strengthened with 0.5% Seakem Gold agarose (30, 31). Following electrophoresis, the gels were washed in an EDTA solution for 20 min, followed by 20 min in an EDTA-free solution. The proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and then blocked and incubated with antibodies against Ser789-caldesmon phosphorylation and total caldesmon for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed and then incubated with anti-mouse and anti-rabbit fluorescent secondary antibodies (Li-Cor) for 45 min at room temperature. The washes were repeated, and the membranes scanned using an Odyssey Infrared Imager. As control, gels were run in the absence of 100 μM MnCl2 in the separating gel, as this is a necessary component to induce the mobility shift of the phosphorylated from the nonphosphorylated proteins. When a 2.7% polyacrylamide gel was used without MnCl2, caldesmon ran off the gel; therefore, a 5% polyacrylamide gel was used. Quantification of the bands was performed using the Odyssey Analysis program. The ratio of phosphorylated caldesmon to total caldesmon, followed by normalization to basal values was used to calculate caldesmon phosphorylation levels. Only the total caldesmon antibody was used for the analysis; the site-specific phospho-Ser789 antibody was used only as a control to ensure there was complete separation of the phosphorylated from unphosphorylated caldesmon.

Immunohistochemistry of phosphorylated MAP kinase.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (48). Briefly, fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin wax. Five-micrometer sections were cut and mounted onto slides. The slides were deparaffinized, and antigen unmasking with a citrate-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was performed. Nonspecific sites were blocked with 5% goat serum and then incubated in anti-active MAP kinase (1:250; Promega) in 1% BSA/PBS for 2 h. The slides were washed with PBS and then incubated in goat-anti-rabbit-biotin vector biotinylated antibody (BA-1000, 1:300, Vector Laboratories) for 30 min in 1% BSA/PBS. Endogenous peroxidases were inactivated with 30% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min and then washed with PBS. Antigen detection was performed with Vectastain avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex kit (Vector Laboratories) as per manufacturer's instructions and diaminobenzidine peroxidase substrate (Vector Laboratories) as per manufacturer's instructions. Slides were counterstained and mounted with Permount. Bright-field images were taken on an Olympus BX40 microscope using Spot imaging software.

Statistics.

All values shown are means ± SE. All “n” values are the number of experiments performed, each using tissues from a different artery. Statistical significance between two means was determined using the Student's t-test. Statistical significance with multiple comparisons was determined using Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction or one-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

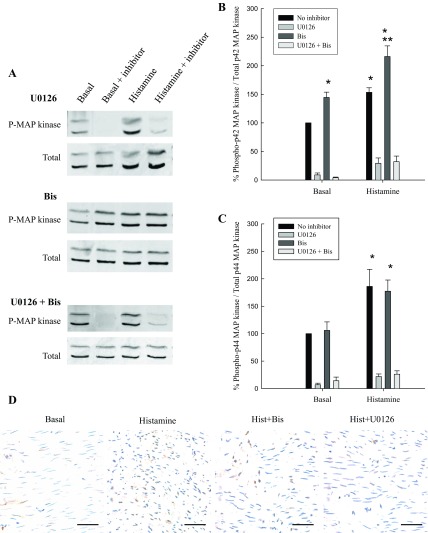

MAP kinase activity was measured by examining dual phosphorylation of MAP kinase in intact medial strips of swine carotid artery at rest and when stimulated with histamine in the presence and absence of inhibitors of MEK (U0126) and/or PKC (Bis). Our laboratory has previously shown that there is a linear relationship between MAP kinase dual phosphorylation and MAP kinase activity, so, hence forth, we will refer to MAP kinase phosphorylation as MAP kinase activity (20). Histamine is a classical and potent in vitro agonist of swine carotid arterial smooth muscle that stimulates receptor G protein-mediated mechanisms (59) and has been shown to be an activator of MAP kinase (1, 25). As expected, histamine significantly increased p42/p44 MAP kinase activity above resting values (Fig. 1). Figure 1A shows a representative Western blot of MAP kinase phosphorylation, and Fig. 1, B and C, shows the quantitative results of several experiments. As expected, exposure to the MEK antagonist U0126 abolished basal and histamine-stimulated p42/p44 MAP kinase activity.

Fig. 1.

MAP kinase activity in unstimulated and stimulated swine carotid artery. A: representative blots of dual phosphorylated (P) MAP kinase. Quantitation of basal and histamine-stimulated p42 (B) and p44 (C) MAP kinase phosphorylation in the absence or presence of MAP kinase kinase (MEK) inhibition with U0126 and/or PKC inhibition with Bis is shown. The presence of U0126, whether used alone or in conjunction with Bis, significantly decreased p42/p44 MAP kinase phosphorylation. Inhibition of PKC with Bis significantly increased basal and histamine-induced p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation, but not p44 MAP kinase phosphorylation. Values are means ± SE for at least 4 determinations. Significance from *basal, no inhibitor, and **histamine, no inhibitor: P ≤ 0.01. Statistics were determined by Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction. D: immunohistochemistry of active MAP kinase in tissues in basal, histamine, histamine plus Bis, and histamine plus U0126 conditions (scale bar = 50 μm).

Interestingly, inhibition of PKC with Bis significantly increased basal and histamine-stimulated values of p42 MAP kinase activity (Fig. 1B). Inhibition of PKC had no effect on either basal or histamine-stimulated levels of p44 MAP kinase activity as they remained elevated (Fig. 1C). This result was unexpected, as PKC has been shown to regulate MAP kinase activity directly and activating kinases upstream of MAP kinase, resulting in the phosphorylation of Tyr185 and Thr189, a requirement for MAP kinase activation (2, 37, 43). The increase of active MAP kinase, which translocates to the nucleus when activated, in response to histamine activation, was not augmented in the presence of Bis, but abolished with U0126 (Fig. 1D). To ensure that Bis was inhibiting PKC, we examined the phosphorylation of a known PKC substrate in vascular smooth muscle, CPI-17 (32). CPI-17 phosphorylation was significantly increased in response to histamine stimulation and was significantly decreased in resting and histamine-stimulated tissues in the presence of Bis (Fig. 2), demonstrating that Bis inhibited PKC. Thus increases in MAP kinase activity in response to inhibition of PKC were not caused by the inability of Bis to effectively inhibit PKC activity.

Fig. 2.

The effect of inhibition of PKC with Bis on CPI-17 phosphorylation. CPI-17 phosphorylation was significantly increased above basal values in response to histamine stimulation. Top: representative blots of CPI-17 phosphorylation in basal conditions, basal plus Bis, histamine, and histamine in the presence of Bis. Bottom: quantitative results of several CPI-17 blots. Histamine and stimulation significantly increased CPI-17 phosphorylation, which was significantly decreased in the presence of Bis. Values are means ± SE for at least 4 determinations. Significance from *basal in the absence of Bis, and **histamine in the absence of Bis: P ≤ 0.007. Statistics were determined by Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction.

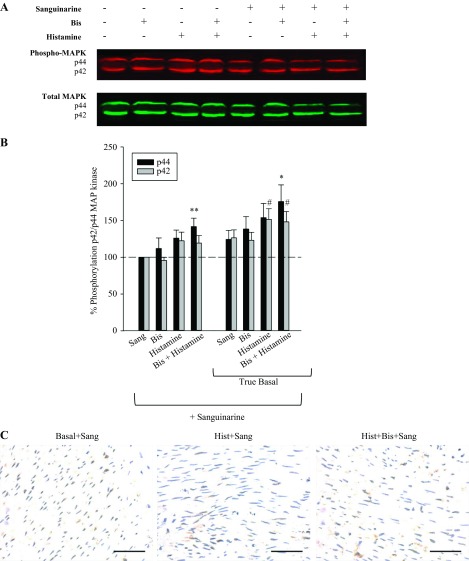

The augmentation of MAP kinase activity in the presence of Bis suggests that PKC may be indirectly regulating MAP kinase, perhaps via MKP-1. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that inhibition of MKP-1 would block the Bis-induced increase in MAP kinase activity. We used the MKP-1 inhibitor sanguinarine to pursue this hypothesis. Figure 3 shows the results of the effect of inhibition of MKP-1 on histamine- and histamine plus Bis-induced increases in p42/p44 MAP kinase activity. Figure 3A shows a representative blot of the effects of sanguinarine on histamine and histamine plus Bis on p42/p44 MAP kinase activity. Figure 3B shows the quantitative results of several such blots. The results in Fig. 3B, left, show the effect of sanguinarine on Bis, histamine, and Bis plus histamine, normalized to basal values in the absence of sanguinarine (compared with Fig. 1B). Sanguinarine blocked the increase in MAP kinase activity following the addition of Bis, histamine, or Bis plus histamine. Figure 3B, right, shows the effect of sanguinarine not normalized to basal values but normalized to the true basal values of MAP kinase activity in the presence of sanguinarine. Figure 3B, right, is shown to demonstrate that sanguinarine increases MAP kinase activity via inhibition of MKP-1 activity. This increase is also observed by immunohistochemistry, and no additional increase with exposure to histamine with or without Bis was observed (Fig. 3C). The finding that sanguinarine increases basal values of MAP kinase activity demonstrates that sanguinarine is indeed inhibiting MKP-1 activity.

Fig. 3.

Effect of inhibition of MKP-1 on p42/p44 MAP kinase activity. A: representative blot of the effect of histamine, Bis, and histamine plus Bis in the presence and absence of 30 μM sanguinarine (Sang) on p42/p44 MAP kinase. B: quantitative results of several blots as shown in A. Left: p42/p44 MAP kinase activity at basal and in the presence of Bis, histamine, or histamine plus Bis, all in the presence of 30 μM Sang (compare with Fig. 1B). Values shown are normalized to basal values in the presence of Sang. Inhibition of MKP-1 abolishes the Bis and histamine-dependent increase in MAP kinase activity. Right: p42/P44 MAP kinase activity at basal and in the presence of Bis, histamine, or histamine plus Bis. Values shown are actual values normalized to basal in the absence of Sang. The significant increase in basal values of p42/p44 MAP kinase in the presence of Sang demonstrates that Sang inhibits MKP-1, resulting in an increase in MAP kinase activity. Values are means ± SE for 8 determinations. *P < 0.05 vs. basal of respective group for p44 MAP kinase. #P < 0.05 vs. basal of respective group for p42 MAP kinase. **P < 0.05 vs. basal plus Sang for p44 Map kinase. Statistics were determined by one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. C: immunohistochemistry of active MAP kinase in basal, histamine, and histamine plus Bis tissues in the presence of Sang (scale bar = 50 μm).

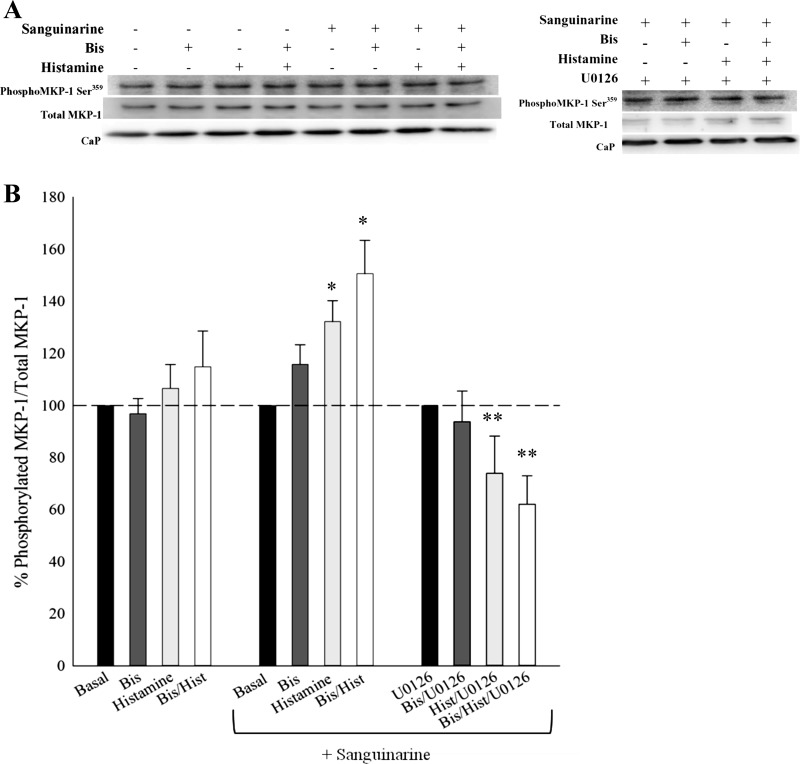

MKP-1 phosphorylation stabilizes and enhances MKP-1 activity (35). Figure 4 shows MKP-1 phosphorylation at Ser359 in response to histamine and histamine plus Bis in the absence and presence of sanguinarine. Neither histamine nor histamine plus Bis increased MKP-1 phosphorylation levels, suggesting that histamine- and Bis-dependent increases in MAP kinase activity are not the result of direct PKC-catalyzed MKP-1 phosphorylation. On the other hand, histamine, Bis, and histamine plus Bis significantly increased MKP-1 phosphorylation levels in the presence of sanguinarine. Therefore, inhibition of MKP-1 increased histamine-induced MKP-1 phosphorylation levels.

Fig. 4.

MKP-1 phosphorylation at Ser359 in unstimulated and histamine-stimulated tissues in the absence or presence of the PKC inhibitor Bis and/or the MAP kinase inhibitor U0126, and/or the MKP-1 inhibitor sanguinarine. A: representative Western blots of MKP-1 Ser359 phosphorylation in all conditions. CaP, calponin; served as a loading control. B, left bar graphs: effect of Bis, histamine, and histamine plus Bis on MKP-1 phosphorylation. MKP-1 phosphorylation was not altered when stimulated with histamine or subjected to Bis or histamine plus Bis. Middle bar graphs: inhibition of MKP-1 with sanguinarine significantly increased histamine-stimulated MKP-1 phosphorylation in the absence or presence of Bis. Right bar graphs: inhibition of MAP kinase with U0126 abolished the sanguinarine-dependent increase in MKP-1 phosphorylation, suggesting that MAP kinase catalyzes MKP-1 phosphorylation. Values are means ± SE for at least 15 determinations. Significance from *respective basal in each panel, no inhibitor, and **MKP-1 phosphorylation in the presence of sanguinarine but absence of U0126: P ≤ 0.05. Statistics were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

MAP kinase has been suggested to phosphorylate MKP-1 to keep MAP kinase activity from increasing to very high levels and initiating cellular damage (6, 35, 46, 55). To test if MKP-1 phosphorylation is catalyzed by MAP kinase, we measured MKP-1 phosphorylation in response to Bis, histamine, and histamine plus Bis in the presence of sanguinarine and in the absence or presence of the MEK inhibitor, U0126. Figure 4A shows representative blots of the effects of sanguinarine on Bis, histamine, and Bis plus histamine on MKP-1 phosphorylation. Figure 4B shows the quantitative results of several such blots. Figure 4B, middle and right, shows that inhibition of MEK with U0126 completely abolished MKP-1 phosphorylation and, in fact, when stimulated with histamine plus Bis, decreased MKP-1 phosphorylation levels below basal values. This suggests that MAP kinase catalyzes MKP-1 phosphorylation in the presence of the inhibitor of MKP-1.

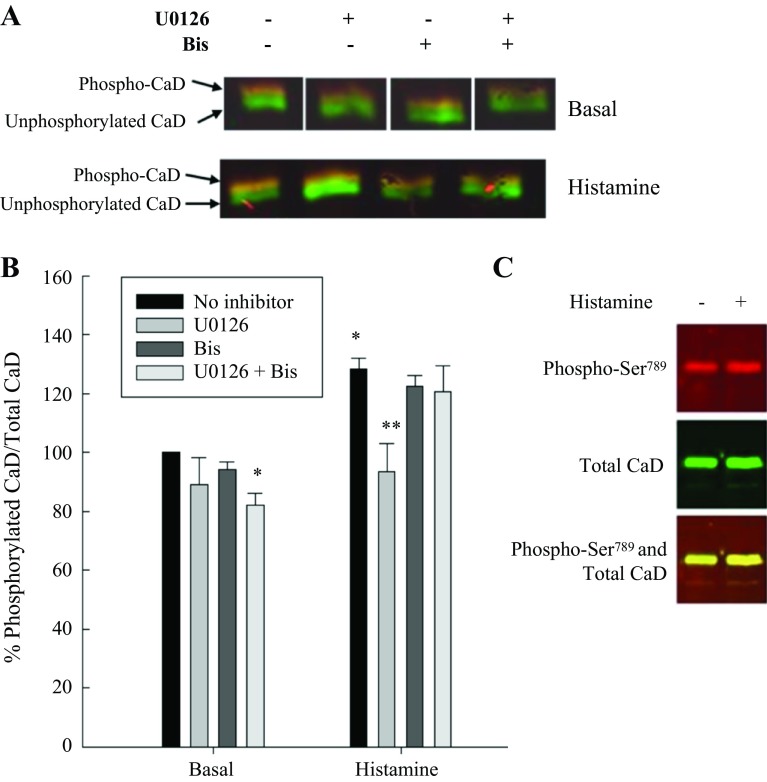

Caldesmon is a known substrate for MAP kinase (1, 20, 42, 56). We determined caldesmon phosphorylation levels at Ser789, the site catalyzed by MAP kinase. Figure 5 shows the caldesmon phosphorylation levels at rest and in response to histamine in the absence and presence of the MEK inhibitor U0126, Bis, and U0126 plus Bis. Histamine significantly increased Ser789 phosphorylation, as expected. Inhibition of MEK with U0126 reduced Ser789-caldesmon phosphorylation levels in resting and stimulated tissues. Inhibition of PKC with Bis had no effect on Ser789-caldesmon phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

MAP kinase and PKC-dependent Ser789-caldesmon (CaD) phosphorylation in unstimulated and stimulated swine carotid artery. A: representative blots of histamine-stimulated Ser789-CaD phosphorylation in the presence of MAP kinase inhibition (U0126), PKC inhibition (Bis), and MAP kinase plus PKC inhibition (U0126 plus Bis). B: quantitation of several such blots of unstimulated and histamine-stimulated Ser789-CaD phosphorylation in the absence or presence of MAP kinase inhibition with U0126 and/or PKC inhibition with Bis. Histamine significantly increased levels of Ser789-CaD phosphorylation. U0126 significantly decreased basal and histamine-stimulated Ser789 phosphorylation, whether used alone or in conjunction with Bis; Bis alone had no effect. Values are means ± SE for at least 4 determinations. Significance from *basal, no inhibitor, and **histamine, no inhibitor: P ≤ 0.01. Statistics were determined by Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction.

Our laboratory and others have presented evidence to suggest that caldesmon is phosphorylated in tissue by at least two kinases. These kinases are most likely MAP kinase and PKC (20, 33, 56). We optimized a recently developed electrophoretic technique that separates phosphorylated from nonphosphorylated proteins, Phos-tag SDS gel electrophoresis, for quantitation of total caldesmon phosphorylation levels (5, 30, 31). Figure 6A shows a representative blot of caldesmon phosphorylation using the Phos-tag technique. As shown in Fig. 6B, inhibition of MEK with U0126 significantly reduced basal values of total caldesmon phosphorylation; inhibition of PKC with Bis had no effect. Also shown in Fig. 6B, histamine significantly increased total caldesmon phosphorylation, which is reduced to basal values in the presence of U0126. Surprisingly, neither Bis alone nor Bis plus U0126 reduced total caldesmon phosphorylation. As a control, Fig. 6C shows the lack of separation of phosphorylated from nonphosphorylated species when MnCl2 is omitted from the gel. MnCl2 is required for Phos-tag to bind to the phosphorylated protein and separate it from the unphosphorylated protein.

Fig. 6.

MAP kinase and PKC-dependent total caldesmon (CaD) phosphorylation in unstimulated and histamine-stimulated swine carotid artery. A: representative blots of total CaD phosphorylation measured using Phos-tag gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting. B: quantitation of several such blots of unstimulated and histamine-stimulated total CaD phosphorylation in the absence or presence of MAP kinase inhibition with U0126 and/or PKC inhibition with Bis. The simultaneous addition of U0126 and Bis significantly decreased basal CaD phosphorylation in unstimulated tissues, but inhibition of either MAP kinase or PKC individually did not alter basal total CaD phosphorylation. Histamine-stimulated total CaD phosphorylation was significantly decreased when exposed to U0126 alone. The presence of Bis had no effect, whether used alone or in conjunction with U0126. Values are means ± SE for at least 4 determinations. Significance from *basal, no inhibitor, and **histamine, no inhibitor: P ≤ 0.01. Statistics were determined by Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction. C: Phos-tag SDS-PAGE in the absence of MnCl2; no mobility shift was observed. Space between the samples on the blots indicates that the samples were run on the same gel but in a different order than presented.

DISCUSSION

Cellular signaling in smooth muscle is a complex series of steps required for basal levels of tone and stimulation-induced contraction in the differentiated contractile phenotype and for secretory and migratory functions in the noncontractile de-differentiated phenotype (18, 28, 36, 54, 63). In this study, we focused on the relationship(s) among PKC, MAP kinase, and MKP-1 in the differentiated, contractile phenotype of vascular smooth muscle. We initially obtained the surprising finding that inhibition of PKC significantly increased basal and stimulated values of p42 but not p44 MAP kinase phosphorylation (Fig. 1) and, henceforth, activity, as we have previously shown that a linear relationship exists between MAP kinase dual phosphorylation and MAP kinase phosphotransferase activity in the swine carotid artery (20). This finding led us to hypothesize that the simplest explanation for an increase in MAP kinase activity following inhibition of PKC was a direct or indirect effect of PKC on MKP-1 (49, 52). Any signaling protein that inhibited MKP-1 activity would result in an increase in MAP kinase activity. Therefore, the major novel findings presented in this study are as follows: 1) inhibition of PKC increases p42 MAP kinase activity and does not alter p44 MAP kinase activity; 2) increases in MAP kinase activity via inhibition of PKC are abolished with MKP-1 inhibition; 3) inhibition of MKP-1 increases MKP-1 phosphorylation, which is catalyzed by MAP kinase; and 4) caldesmon is most likely a downstream substrate of MAP kinase following inhibition of PKC. These interactions among PKC, MAP kinase, MKP-1, and caldesmon have, to the best of our knowledge, not been previously reported in smooth muscle and as such represent novel pathways in vascular smooth muscle in the contractile phenotype.

Our hypothesis that PKC activates a MKP-1, which would decrease MAP kinase phosphorylation and regulate MAP kinase activity in resting and stimulated tissues, has been shown in nonsmooth muscle tissues. Of the nine different mammalian MAP kinase phosphatases identified, MKP-1 has been the only one shown to be activated by PKC in macrophages and cardiac fibroblasts (49, 52). Our interpretation of the results in the present study depends on the specificity of sanguinarine for MKP-1. Sanguinarine is a relatively specific inhibitor of MKP-1 (9, 53), but has also been suggested to inhibit the Na+-K+-ATPase (44). We tested this possibility by subjecting the carotid arterial tissues to 10 μM ouabain in the absence and presence of sanguinarine. Ouabain-induced contractions result from inhibition of the Na+-K+-ATPase, which inhibits the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and increases cytosolic calcium (39). Sanguinarine did not decrease ouabain-induced contractions in our arterial tissues (data not shown). Rembold's laboratory (41) has suggested that ouabain-induced contractions are not a direct effect on the vascular smooth muscle cell but release of neurotransmitters from nerve endings within the tissue. We used tetrodotoxin to block nerves within our tissue and exposed the tissues to ouabain; tetrodotoxin did not alter the ouabain induced vascular contraction (data not shown). Therefore, we suggest that sanguinarine is an inhibitor of MKP-1 in our vascular preparation. This is supported by the fact that sanguinarine increased basal levels of MAP kinase activity (Fig. 3).

One of the strongest pieces of information to support our hypothesis that PKC regulates MAP kinase activity via MKP-1 was shown in Fig. 3. Inhibition of MKP-1 with sanguinarine almost completely abolished the increase in MAP kinase activity in the presence of the PKC inhibitor, Bis. This is what one would expect if the actions of PKC were via effects on MKP-1: blockade of MKP-1 would block the effect of Bis.

In the present study, we demonstrated that caldesmon is phosphorylated at Ser789 at rest and in response to histamine; both states were sensitive to inhibition of MAP kinase. Inhibition of MKP-1 also increased MAP kinase catalyzed caldesmon phosphorylation, but the effect was modest (data not shown). Caldesmon's inhibitory actions can be reversed by phosphorylation at Ser789 catalyzed by MAP kinase (1); therefore, caldesmon may be the downstream substrate for MAP kinase in this signaling pathway. Our laboratory has previously shown that knock-down of caldesmon in carotid arterial tissues results in a constitutively active muscle (16, 45), so the precise regulation of MAP kinase activity may be important in regulating caldesmon's brake function to prevent contractions in the absence of a stimulus or in modulation of a pool of active but unphosphorylated myosin (22).

In our opinion, one of the more interesting findings was MKP-1 phosphorylation catalyzed by MAP kinase. In the presence of sanguinarine, MKP-1 phosphorylation levels were significantly increased (Fig. 4). This increase in phosphorylation was abolished in the presence of the MEK inhibitor, U0126. We propose that this is a negative feedback loop ensuring that MAP kinase activity does not increase unrestrained during conditions of MKP-1 inhibition. Due to the numerous actions that MAP kinase exerts on cellular signaling, the suggestion that MAP kinase can reduce its own activity by phosphorylation and activation of MKP-1 is appealing. Using human vascular smooth muscle cells, Kim et al. (29) showed that PKC-α inhibited MAP kinase activity by induction of MKP-1, results consistent with our findings where inhibition of PKC increased MAP kinase activity. In macrophages, it was suggested that MAP kinase phosphorylates and stabilizes MKP-1 (12). A recent study used sanguinarine to inhibit MKP-1 and noted increased MAP kinase and JNK activity (4); a negative feedback pathway similar in effect to our MAP kinase catalyzed MKP-1 phosphorylation.

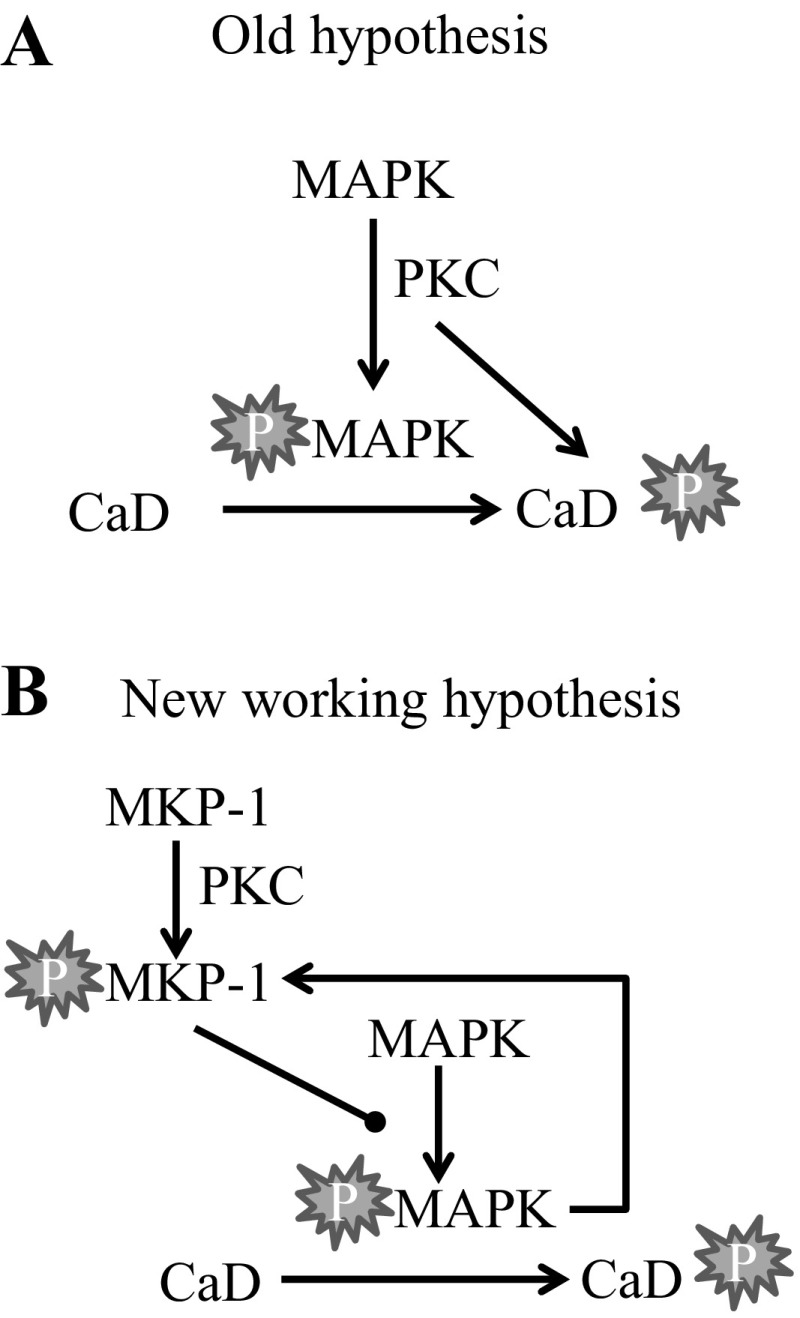

In summary, based on the findings in this study, we propose the model shown in Fig. 7. Agonist stimulation of vascular smooth muscle increases PKC activity, which, in turn, increases MKP-1 activity and maintains MAP kinase activity at submaximal values. Inhibition of PKC decreases MKP-1 activity, resulting in enhanced p42 MAP kinase activity. Complete inhibition of MKP-1 results in increased MAP kinase activity, which, in turn, phosphorylates and increases MKP-1 activity, providing a negative feedback mechanism to ensure that MAP kinase does not increase in an unrestrained manner. Caldesmon is a likely downstream substrate for MAP kinase, reversing the inhibitory actions of caldesmon on actin-activated myosin ATPase activity and thus increasing contraction. Further studies are needed to determine whether PKC directly or indirectly regulates MKP-1 and whether downstream substrates, in addition to caldesmon, are involved.

Fig. 7.

Our working hypothesis based on the results of this study. A: our old hypothesis where protein kinase C (PKC) activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) by directly or indirectly inducing MAPK phosphorylation (P). Activated MAPK and PKC both phosphorylate caldesmon (CaD) with no feedback pathways. B: our new working hypothesis where MAPK and PKC activity are increased by agonist stimulation. PKC regulates MAPK activity levels by activating or stabilizing mitogen-activated phosphatase-1 (MKP-1). MKP-1 dephosphorylates MAPK, thus inhibiting MAPK activity. Activated MAPK phosphorylates CaD in addition to MKP-1, serving as a feedback mechanism to stabilize MKP-1 activity. This tight regulation of MAPK will ensure that MAPK activity does not increase in an unrestrained manner.

GRANTS

This work was supported, in part, by funds from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO-1 DK 85734 (R. S. Moreland) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants RO-1 HL115575 and RO-1 HL117724 (M. V. Autieri).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.M.T., S.S., H.K.E., and R.S.M. conception and design of research; D.M.T., S.S., H.K.E., and F.K. performed experiments; D.M.T., S.S., H.K.E., F.K., M.V.A., and R.S.M. analyzed data; D.M.T., H.K.E., M.V.A., and R.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; D.M.T., S.S., H.K.E., and F.K. prepared figures; D.M.T. and R.S.M. drafted manuscript; D.M.T., S.S., H.K.E., M.V.A., and R.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; D.M.T., S.S., H.K.E., F.K., M.V.A., and R.S.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam L, Hathaway D. Identification of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation sequences in mammalian h-caldesmon. FEBS Lett 322: 56–60, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari H, Teng B, Nadeem A, Roush K, Martin K, Schnermann J, Mustafa S. A1 adenosine receptor-mediated PKC and p42/p44 MAPK signaling in mouse coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1032–H1039, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baas AS, Berk BC. Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by H2O2 and O2 in vascular smooth muscles. Circ Res 77: 29–36, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bavaria MN, Jin S, Ray RM, Johnson LR. The mechanism by which MEK/ERK regulates JNK and p38 activity in polyamine depleted IEC-6 cells during apoptosis. Apoptosis 19: 467–479, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhetwal BP, Sanders KM, An C, Trappanese DM, Moreland RS, Perrino BA. Ca2+ sensitization pathways accessed by cholinergic neurotransmission in the murine gastric fundus. J Physiol 591: 2971–2986, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brondello JM, Pouyssegur J, McKenzie FR. Reduced MAP kinase phosphatase-1 degradation after p42/p44 MAPL dependent phosphorylation. Science 286: 2514–2517, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao W, Sohn UD, Bitar KN, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. MAPK mediates PKC-dependent contraction of cat esophageal and lower esophageal sphincter circular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G86–G95, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmines PK, Fallet RW, Che Q, Fujiwara K. Tyrosine kinase involvement in renal arteriolar constrictor response to angiotensin II. Hypertension 37: 569–573, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Wang H, Zhang R, Wang H, Peng Z, Sun R, Tan Q. Microinjection of sanguinarine into the ventrolateral orbital cortex inhibits Mkp-1 and exerts an antidepressant-like effect in rats. Neurosci Lett 506: 327–331, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childs TJ, Mak AS. Smooth-muscle mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase: purification and characterization, and the phosphorylation of caldesmon. Biochem J 296: 745–751, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Childs TJ, Watson MH, Sanghera JS, Campbell DL, Pelech SL, Mak AS. Phosphorylation of smooth muscle caldesmon by mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and expression of MAP kinase in differentiated smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 267: 22853–22859, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowell S, Wancket LM, Shakibi Y, Xu P, Xue J, Samavati L, Nelin D, Liu Y. Post-translational regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP)-1 and MKP-2 in macrophages following lipopolysaccharide stimulation: the role of the C termini of the phosphatases in determining their stability. J Biol Chem 289: 28753–28764, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiSalvo J, Steusloff A, Semenchuk L, Satoh S, Kolquist K, Pfitzer G. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors suppress agonist-induced contraction in smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 190: 968–974, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duff JL, Marrero MB, Paxton WG, Charles CH, Lau LE, Bernstein KE, Berk BC. Angiotension II induces 3CH134, a protein-tyrosine phosphatase in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 268: 26037–26040, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duff JL, Monia BP, Berk BC. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase is regulated by MAP kinase phosphatase (MKP-1) in vascular smooth muscle cells. Effect of actinomycin D and antisense oligonucleotides. J Biol Chem 270: 7161–7166, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earley JJ, Su X, Moreland RS. Caldesmon inhibits active crossbridges in unstimulated vascular smooth muscle. An antisense oligodeoxynucleotide approach. Circ Res 83: 661–667, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerthoffer WT. Signal-transduction pathways that regulate visceral smooth muscle function. III. Coupling of muscarinic receptors to signaling kinases and effector proteins in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288: G849–G853, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerthoffer WT, Schaafsma D, Sharma P, Ghavami S, Halayko AJ. Motility, survival, proliferation. Compr Physiol 2: 256–281, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerthoffer WT, Yamboliev IA, Shearer M, Pohl J, Haynes R, Dang S, Sato K, Sellers JR. Activation of MAP kinases and phosphorylation of caldesmon in canine colonic smooth muscle. J Physiol 495: 597–609, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorenne I, Su X, Moreland RS. Inhibition of p42 and p44 MAP kinase activity does not alter smooth muscle contraction in swine carotid artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H131–H138, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal R, Mittal A, Chu N, Shi L, Zhang L, Longo L. Maturation and the role of PKC-mediated contractility in ovine cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H2242–H2252, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haeberle JR, Hemric ME. A model for the coregulation of smooth muscle actomyosin by caldesmon, calponin, tropomyosin, and the myosin regulatory light chain. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 1400–1409, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedges J, Oxhorn B, Carty M, Adam L, Yamboliev I, Gerthoffer WT. Phosphorylation of caldesmon by Erk MAP kinases in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C718–C726, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horowitz A, Menice C, Laporte R, Morgan K. Mechanisms of smooth muscle contraction. Physiol Rev 76: 967–1003, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katoch SS, Moreland RS. Agonist and membrane depolarization induced activation of MAP kinase in swine carotid artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H222–H229, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalil RA, Menice CB, Wang CL, Morgan KG. Phosphotyrosine-dependent targeting of mitogen-activated protein kinase in differentiated contractile vascular cells. Circ Res 76: 1101–1108, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil RA, Morgan KG. PKC-mediated redistribution of mitogen-activated protein kinase during smooth muscle cell activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 265: C406–C411, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HR, Appel S, Vetterkind S, Gangopadhyay SS, Morgan KG. Smooth muscle signaling pathways in health and disease. J Cell Mol Med 12: 2165–2180, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SY, Kwon YW, Jung IL, Sung JH, Parl SG. Tauroursdeoxycholate (TUDCA) inhibits neointimal hyperplasia by suppression of ERK via PKCα-mediated MKP-1 induction. Cardiovasc Res 92: 307–316, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikura E, Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics 5: 749–757, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikura E, Koike T. Separation and detection of large phosphoproteins using Phos-tag SDS-PAGE. Nat Protoc 4: 1513–1521, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitazawa T, Eto M, Woodsome TP, Khalequzzman M. Phosphorylation of the myosin phosphatase targeting subunit and CPI-17 during Ca2+ sensitization in rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol 546: 879–889, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kordowska J, Huang R, Wang CL. Phosphorylation of caldesmon during smooth muscle contraction and cell migration or proliferation. J Biomed Sci 13: 159–172, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Je H, Malek S, Morgan K. ERK 1/2-mediated phosphorylation of myometrial caldesmon during pregnancy and labor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R192–R199, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li CY, Yang LC, Guo K, Wang YP, Li YG. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1: a critical phosphatase manipulating mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Med 35: 1095–1102, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mack CP. Signaling mechanisms that regulate smooth muscle cell differentiation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 1495–14505, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsubara M, Tamura T, Ohmori K, Hasegawa K. Histamine H1 receptor antagonist blocks histamine-induced proinflammatory cytokine production through inhibition of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C, Raf/MEK/ERK and IKK/I kappa B/NF-kappa B signal cascades. Biochem Pharmacol 69: 433–439, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metzler B, Hu Y, Sturm G, Wick G, Xu Q. Induction of mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase-1 by arachidonic acid in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 273: 33320–33326, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreland RS, Major T, Webb RC. Contractile responses to ouabain and K+-free solution in aortae from hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 250: H612–H619, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owens DM, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signaling by dual-specificity protein phosphatases. Oncogene 26: 3203–3213, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rembold CM, Richard H, Chen XL. Na+-Ca2+ exchange, myoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, and contraction of arterial smooth muscle. Hypertension 19: 308–313, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roman HN, Zitouni NB, Kachmer L, Benedetti A, Sobieszek A, Lauzon AM. The role of caldesmon and its phosphorylation by ERK on the binding force of unphosphorylated myosin to actin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840: 3218–3225, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schonwasser D, Marais R, Marshall C, Parker P. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol Cell Biol 18: 790–798, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seifen E, Adams RJ, Reimer RK. Sanguinarine: a positive inotropic alkaloid which inhibits cardiac Na+,K+-ATPase. Eur J Pharmacol 60: 373–377, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smolock EM, Trappanese DM, Chang S, Wang TC, Titchenell P, Moreland RS. siRNA mediated knock down of h-caldesmon in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1930–H1939, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sohaskey ML, Ferrell JE Jr. Activation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), but not c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase, induces phosphorylation and stabilization of MAP phosphatase XCL 100 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Biol Cell 13: 454–468, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature 372: 231–236, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sommervile LJ, Xing C, Keleman SE, Eguchi S, Autieri MV. Inhibition of allograft inflammatory factor-1 expression reduces development of neointimal hyperplasia and p38 kinase activity. Cardiovasc Res 81: 206–215, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stawowy P, Goetze S, Margeta C, Fleck E, Graf K. LPS regulate ERK1/2-dependent signaling in cardiac fibroblasts via PKC-mediated MKP-1 induction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 303: 74–80, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steusloff A, Paul E, Semenchuk LA, Di Salvo J, Pfitzer G. Modulation of Ca2+ sensitivity in smooth muscle by genistein and protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Arch Biochem Biophys 320: 236–242, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun H, Charles CH, Lau LF, Tonks NK. MKP-1 (3CH134), an immediate early gene product, is a dual specificity phosphatase that dephosphorylates MAP kinase in vivo. Cell 75: 487–493, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valledor A, Xaus J, Comalada M, Soler C, Celada A. Protein kinase C epsilon is required for the induction of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Immunol 164: 29–37, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogt A, Tamewitz A, Skoko J, Sikorski RP, Giuliano KA, Lazo JS. The benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloid, sanguinaraine, is a selective, cell-active inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. J Biol Chem 280: 19078–19086, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wamhof BR, Bowles DK, Owens GK. Excitation-transcription coupling in arterial smooth muscle. Circ Res 98: 868–878, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wancket LM, Frazier WJ, Liu Y. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP)-1 in immunology, physiology, and disease. Life Sci 90: 237–248, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang CL. Caldesmon and the regulation of cytoskeletal functions. Adv Exp Med Biol 644: 250–272, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang TC, Kendig DM, Smolock EM, Moreland RS. Roles of protein kinase C and Rho kinase in carbachol induced contraction of rabbit bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1534–F1542, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang TC, Kendig DM, Trappanese DM, Smolock EM, Moreland RS. Phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate-induced, protein kinase C-mediated contraction of rabbit bladder smooth muscle. Front Pharmacol 2: 1–12, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watkins R, Davidson I. Action of histamine on phasic and tonic components of vascular smooth muscle contraction. Experientia 36: 582–584, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watts SW. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway via the 5-HT2A receptor. Ann NY Acad Sci 861: 162–168, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wier WG, Morgan KG. Alpha1-adrenergic signaling mechanisms in contraction of resistance arteries. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 150: 91–139, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woodsome T, Eto M, Everett A, Brautigan D, Kitazawa T. Expression of CPI-17 and myosin phosphatase correlates with Ca2+ sensitivity of protein kinase c-induced contraction in rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol 535: 553–564, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie Y, Zhang L, Longo L. Smooth muscle cell-differentiation in vitro: models and underlying molecular mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 1584–1494, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao Y, Zhang L, Longo L. PKC-induced ERK1/2 interactions and downstream effectors in ovine cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R164–R171, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]