Abstract

An increase of toxic bile acids such as glycochenodeoxycholic acid occurs during warm ischemia reperfusion causing cholestasis and damage in hepatocytes and intrahepatic biliary epithelial cells. We aim to test antiapoptosis effects of ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide under cholestatic induction by glycochenodeoxycholic acid treatment of mouse hepatocytes and hypoxia induction by cobalt chloride treatment of intrahepatic biliary epithelial cancer Mz-ChA-1cell line. Such treatments caused marked increases in apoptosis as evidenced by activation of caspase 3, caspase 8 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Co-treatment with ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide significantly inhibited these increases. Interestingly, ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide was able to increase expression of antiapoptotic cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein in both cell types. Ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide also prevented the decreases of myeloid cell leukemia sequence-1 protein in both experimental systems, and this protection was due to ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide’s ability to inhibit ubiquitination-mediated degradation of myeloid cell leukemia sequence-1, and to increase the phosphorylation of GSK-3β. In addition, ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide was able to prevent the decreased expression of another antiapoptotic cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 2 in cobalt chloride-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. Hence, ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide mediated cytoprotection against apoptosis during toxic bile-acid and ischemic stresses by a mechanism involving accumulation of cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein, myeloid cell leukemia sequence-1 and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 2 proteins. Ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide may thus be used as an agent to prevent hepatic ischemia reperfusion.

Keywords: Bile acid toxicity, hypoxia, cytoprotective drug, antiapoptosis proteins, proteasome-mediated degradation

Introduction

Hemorrhagic shock, surgical resection and liver transplantation result in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion (I/R).1 In addition to injury to hepatocytes, this pathological process causes injury in the intrahepatic vascular and biliary systems seen as hepatic thrombosis or stenosis2 and biliary strictures.3,4 This leads to a high risk of liver dysfunctions and failure of liver transplantation. Regarding liver transplantation, the prevention of hepatic I/R injury has been a major research focus for therapeutic development owing to the scarcity of donated livers. Hepatic I/R can affect both the hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells with apoptosis as the major mechanism of injury. Biliary strictures induced by hepatic I/R results in slower flow rates of bile and with higher proportion of bile salts than phospholipids,5 and this is a condition seen as cholestasis in livers with biliary obstruction.6 Toxic hydrophobic bile acids, such as glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA), accumulate in cholestatic livers causing apoptosis and injury in hepatocytes7 and the bile ducts.8

Protective strategies to prevent hepatic I/R injury include the use of a single hepatoprotectant such as antioxidant silibinin,9 taurine10 and tauro-ursodeoxycholic acid (tauro-UDCA)11 as well as the use of therapeutic cocktails.12 Tauro-UDCA which is a hydrophilic bile acid has been shown to inhibit toxic bile acid-induced apoptosis in primary hepatocytes.13 In our laboratory, an amphiphilic bile acid-phospholipid conjugate so-called ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide (UDCA-LPE) was designed as a hepatoprotective agent in inhibiting TNF-α-induced apoptosis being superior to its unconjugated metabolites UDCA and lysophosphatidylethanolamine.14 UDCA-LPE has been recently shown to be superior to tauro-UDCA during palmitate-induced apoptosis.15 In this study, we evaluated a potential use of UDCA-LPE in amelioration of I/R-associated apoptosis in two in vitro experimental settings: GCDCA-induced apoptosis in mouse hepatocytes and hypoxia-induced apoptosis in human intrahepatic biliary Mz-ChA-1 cell line. We herein demonstrated that UDCA-LPE rendered protection in part by an upregulation of antiapoptosis genes known to antagonize intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis. UDCA-LPE may be useful as a cytoprotective agent against hepatic I/R injury.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

UDCA-LPE was synthesized by ChemCon (Freiburg, Germany) according to published procedure.14 GCDCA and cobalt chloride (CoCl2) were from Sigma (Taufkirchen, Germany). Anticleaved PARP-1 (clone E51) and β-tubulin (clone EP1331Y) antibodies were from Epitomics, Hamburg, Germany. Anticleaved caspase 3 (clone 5A1E), cleaved caspase 8 (clone Asp387), cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (cFLIP; catalog #3210), phospho-GSK-3β (clone 5B3) and GAPDH antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Frankfurt, Germany). Anti-Mcl-1 (sc-819) and ubiquitin (sc-9133) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany). Anti-cIAP2 antibody (clone F30-2285) was from BD Pharmingen (Heidelberg, Germany). Rabbit and mouse secondary HRP-coupled antibody were respectively obtained from Epitomics and Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Hepatocyte isolation and treatment

Hepatocytes were isolated from 7- to 10-week-old C57/BL6 mice (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Sulzfeld, Germany) by using a two-step collagenase perfusion technique and purified by Percoll. Hepatocytes were plated and cultured for 2 h in William’s E medium with GlutaMAX™ (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 1% penicillin and streptomycin and 4% neonatal calf serum to allow adherence. After removal of dead hepatocytes, hepatocytes were treated with GCDCA with and without UDCA-LPE in serum-free William’s E medium for 15 h.

Mz-ChA-1 cultures and treatment

Mz-ChA-1 was a human biliary adenocarcinoma cell line16 which was subjected to treatment with hypoxia mimetic CoCl2. Mz-ChA-1 cells were cultured in DMEM with 4.5 mg/dL glucose (PAA Laboratories GmbH) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FCS. Mz-ChA-1 cells were plated and cultured in complete medium for 1 day, and in serum-free medium for further 48 h. Mz-ChA-1 cells were subsequently treated with 750 µM CoCl2 with and without UDCA-LPE in serum-free medium for 24 h.

Biochemical assays

Following treatment, mouse hepatocytes or Mz-ChA-1 cells were washed and lyzed with 1% Triton X-100 PBS, and subjected to determination of caspase 3/7 and caspase 8 activities using CaspaseGlo kits (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Caspase activities were measured with a Fluostars Optima (BMG Labtech GmbH, Germany). Data presented on caspase activity assays were obtained from at least three reproducible experiments.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Treated cells were lysed and centrifuged at 13,000 g, 4℃ for 15 min. Proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a PDVF membrane. Blots were probed with a primary antibody followed by a secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized using Luminata Forte ECL reagent (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Image J was used to quantify the density of protein bands of the targets and loading control GAPDH or β-tubulin. The ratio of protein target/loading control was calculated, and data were normalized to the ratio of control experiment and reported as % control. For immunoprecipitation (IP), cell lysates with 250–500 µg proteins were treated with 1 µg antibody and 20 µL protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Samples were incubated overnight at 4℃ with rotation. Beads were washed and added with sample buffer. Proteins in immunoprecipitates were separated by electrophoresis followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-Mcl-1 or anti-ubiquitin antibody.

Gene expression by RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using QIAGEN RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized from 2 µg RNA using a Maxima First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany). Expression of cFLIP was analysed by real-time PCR using Applied Biosystems TaqMan® gene expression assays with TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix, and run on an Applied Biosystem 7500. The expression level of targets in quadruplets was calculated using Δ–Ct transformation method, and determined as a ratio of target gene normalized to house-keeping gene GAPDH.

Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as the means ± SD. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. Significance using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons was determined by using Graphpad Prism 5.

Results

UDCA-LPE protects mouse hepatocytes against GCDCA-induced apoptosis

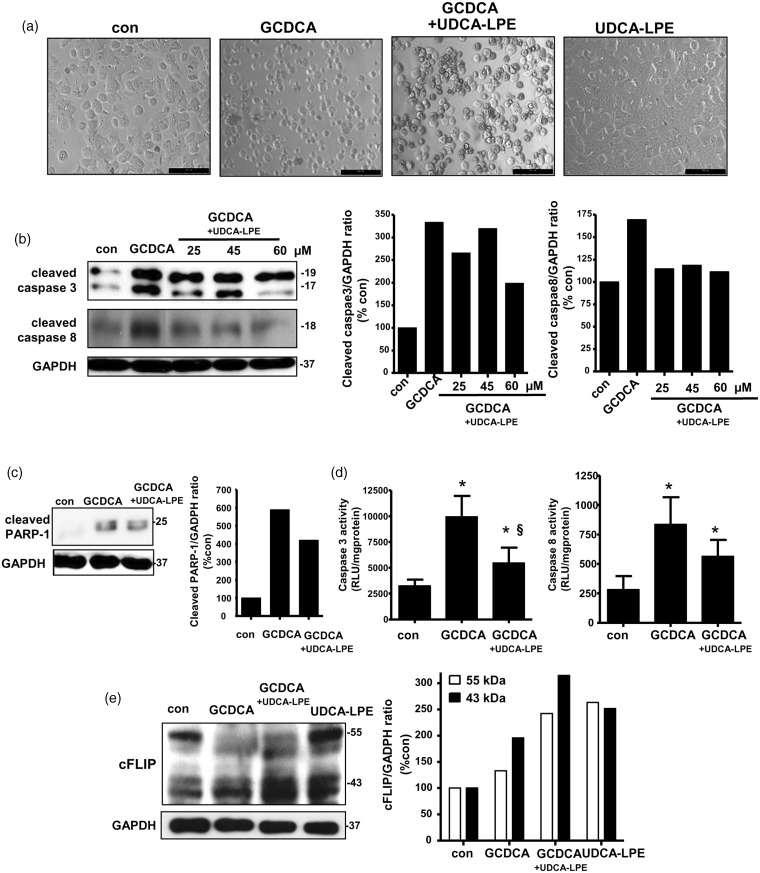

We utilized toxic bile salt GCDCA to treat mouse hepatocytes as a model of cholestasis.7,8 GCDCA treatment induces apoptosis through the classical intrinsic mitochondria17 and ER stress18 as well as extrinsic Fas death-receptor7 via caspase 818 pathways. Mouse hepatocytes treated with 50 µM GCDCA for 15 h showed cell clumping and rounding in every cell (Figure 1a). This was prevented by co-treatment with 60 µM UDCA-LPE as many cells were still able to adhere on culture plates. Treatment of mouse hepatocytes treated with 60 µM UDCA-LPE alone did not cause any morphological changes indicating that UDCA-LPE was not toxic to mouse hepatocytes. In our studies, we utilized pro-apoptosis antibodies specific for cleaved or fragmented proteins. We observed that GCDCA treatment caused an elevated expression of cleaved caspase 3 (17-kDa and 19-kDa fragments) and cleaved caspase 8 (18-kDa fragment) (Figure 1b) as well as cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1; 25-kDa fragment) (Figure 1c). By densitometric analyses of the target protein normalized to GAPDH, we observed that GCDCA-induced increases of these proteins were inhibited by UDCA-LPE, particularly when used at 60 µM. Consistently, an elevation of caspase 3 activity by GCDCA was inhibited by 60 µM UDCA-LPE co-treatment (§, P < 0.05, GCDCA versus GCDCA + UDCA-LPE), while only a trend for an inhibition by UDCA-LPE was observed for caspase 8 activity (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide (UDCA-LPE) protected against glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA)-induced apoptosis in mouse hepatocytes. Mouse hepatocytes were treated with 50 µM GCDCA with or without UDCA-LPE for 15 h. (a) Phase contrast pictures were from control, GCDCA, GCDCA + 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes. (b) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (right) of cleaved caspase 3 (17 kDa and 19 kDa) and cleaved caspase 8 (18 kDa) proteins were obtained from control, GCDCA, GCDCA + 25 µM, 45 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes. Densitometric analyses of cleaved caspase 3 of combined 17-kDa and 19-kDa bands were performed. (c) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (right) of cleaved PARP-1 (25 kDa) protein were obtained from control, GCDCA and GCDCA + 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes. (d) Activities of caspase 3 (left) and caspase 8 (right) were obtained from control, GCDCA, and GCDCA + 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes. Data were mean ± SD, N = 4; *, P < 0.05, con versus GCDCA or UDCA-LPE; §, P < 0.05, GCDCA versus GCDCA + UDCA-LPE. (e) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (right) of cFLIP proteins at 55 kDa and 43 kDa were obtained from control, GCDCA, GCDCA + 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes. Western blot data were representatives from at least two independent experiments

We previously reported that UDCA-LPE protection against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-induced apoptosis in HeG2 cells14 was mediated by its ability to upregulate cFLIP, which is an inhibitor of caspase 8.19 To a lesser extent than UDCA-LPE, densitometric analyses revealed that GCDCA also increased expression of anti-apoptotic cFLIP proteins detectable at 55 kDa and 43 kDa (Figure 1e). UDCA-LPE and GCDCA co-treatment caused significant increases of 43-kDa cFLIP protein to a greater extent than a single treatment. It has been shown that GCDCA treatment of human hepatocellular cancer cell line Huh-720 decreases protein expression of cFLIP while increasing cFLIP phosphorylation. Further study is required whether GCDCA increases cFLIP phosphorylation and whether this could prevent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of cFLIP.21 It is speculated that the observed increased cFLIP by GCDCA may reflect a protective mechanism in order to ameliorate apoptotic injury triggered by GCDCA.

UDCA-LPE protects Mz-ChA-1 cells from hypoxia mimetic-induced apoptosis

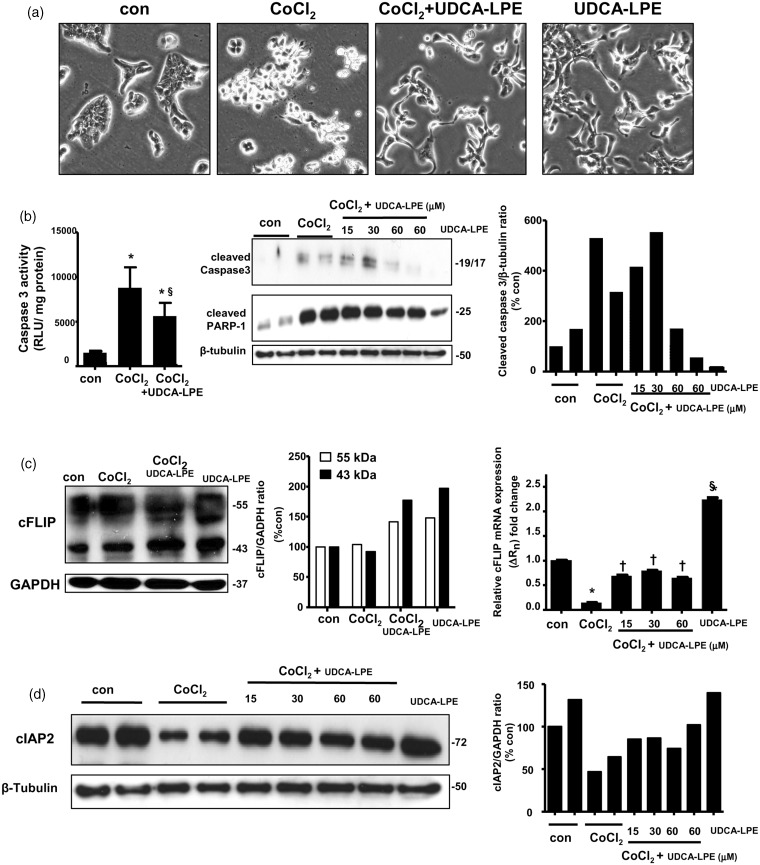

CoCl2 is cytotoxic to a range of cell types via induction of apoptosis and necrosis by inducing expression of hypoxia-inducible-factor-1α, therefore CoCl2 is used as an experimental hypoxia mimetic.22 It is known that apoptosis induction by CoCl2 occurs with mechanisms involving mitochondria and death-receptor Fas23 as evidenced by activation of caspase 3 and 8.24 Because biliary epithelial cells are target cells for injury induced by hypoxia, we chose biliary adenocarcinoma Mz-ChA-1 cell line as a model system. Mz-ChA-1 cells were precultured in complete medium for 3 days and in serum-free medium for further 24 h. These cells were harvested following hypoxia mimetic CoCl2 treatment in serum-free medium for 48 h. Phase-contrast pictures in Figure 2(a) showed that 750 µM CoCl2 caused cell rounding and partial detachment showing floating appearance. There was a significant reduced number of floating cells during CoCl2 and UDCA-LPE co-treatment. It was observed that UDCA-LPE with and without CoCl2 co-treatment induced morphological changes into elongated and spindle shape indicating that UDCA-LPE itself may have affected expression of cytoskeletal proteins. Concomitant with cell rounding appearance, 750 µM CoCl2 treatment caused increases of caspase 3 activities (*, P < 0.05, con versus CoCl2) as well as expression of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP-1 proteins (Figure 2b). The increases were suppressed by co-treatment with UDCA-LPE when used at 60 µM. Treatment of Mz-ChA-1 cells with UDCA-LPE alone had little or no effects on expression of these pro-apoptotic proteins.

Figure 2.

Ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide (UDCA-LPE) protected against cobalt chloride (CoCl2)-induced apoptosis in Mz-Cha-1 cells. Mz-ChA-1 cells were treated with 750 µM CoCl2 with or without UDCA-LPE for 24 h. (a) Phase contrast pictures were from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. (b) Left-hand figure shows caspase 3 activities obtained from control, CoCl2 and CoCl2 + 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. Data are mean ± SD, N = 4; *, P < 0.05, con versus CoCl2 or UDCA-LPE; §, P < 0.05, CoCl2 versus CoCl2 + UDCA-LPE. Western blot (middle) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (right) of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP-1 proteins were obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 15 µM, 30 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. Densitometric analyses of cleaved caspase 3 of combined 17-kDa and 19-kDa bands were performed. (c) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (middle) of cFLIP proteins at 55 kDa and 43 kDa were obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. Right-hand figure shows cFLIP mRNA expression obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 15 µM, 30 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. (d) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (middle) of cIAP2 protein were obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 15 µM, 30 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells

Under our experimental conditions, hypoxia mimetic CoCl2 did not alter expression of cFLIP proteins as seen by densitometric analyses (Figure 2c). Similar to mouse hepatocytes, UDCA-LPE increased expression of cFLIP proteins in Mz-ChA-1 cells with or without CoCl2 co-treatment. The ability of UDCA-LPE to increase cFLIP was also found on the mRNA levels (Figure 2c). CoCl2 decreased cFLIP mRNA expression (*, P < 0.05, con versus CoCl2), and UDCA-LPE co-treatment rescued these decreases (†, P < 0.05, CoCl2 versus CoCl2+UDCA-LPE). The latter was due to the ability of UDCA-LPE alone to markedly increase cFLIP mRNA (§, P < 0.05, con versus UDCA-LPE). Similar to cFLIP protein, we did not observe any marked increases of cleaved caspase 8 protein or caspase 8 activities by CoCl2 treatment (data not shown). Apparently CoCl2 did not markedly activate extrinsic apoptosis involving caspase 8. The discrepancy between cFLIP mRNA and protein expression by CoCl2 is not clearly understood, and it is speculated that the observed accumulated cFLIP protein during CoCl2 could be due to prevention of its proteasomal degradation.21 Unfortunately, our cFLIP antibody was not appropriate for pull-down assays to investigate this pathway. Nonetheless under our experimental conditions, UDCA-LPE’s ability to increase cFLIP protein alone and in combination with CoCl2 may have caused an impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system causing increased accumulation of other short-lived proteins,25 such as myeloid cell leukemia sequence-1 (Mcl-1) and cIAP2.

We have reported previously that UDCA-LPE increases the levels of cAMP which in part can contribute to protection against apoptosis.15 cAMP has been shown to upregulate expression of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 (cIAP2).26 Concurrently, we found that CoCl2 decreased expression of cIAP2 protein detectable at 72 kDa, and co-treatment with UDCA-LPE at 15, 30 and 60 µM rescued these decreases as seen by densitometric analysis (Figure 2d). Under our conditions, CoCl2 did not alter expression of cIAP1 protein (data not shown). Unlike cFLIP, treatment with UDCA-LPE alone did not increase protein expression of cIAP2 (Figure 2d) and cIAP1 (data not shown). Our antibodies against cIAP1 and cIAP2 were specific for humans and therefore they could not be used to investigate the role of these proteins during GCDCA-induced apoptosis in mouse hepatocytes.

UDCA-LPE protection is in part by a mechanism of an inhibition of Mcl-1 degradation

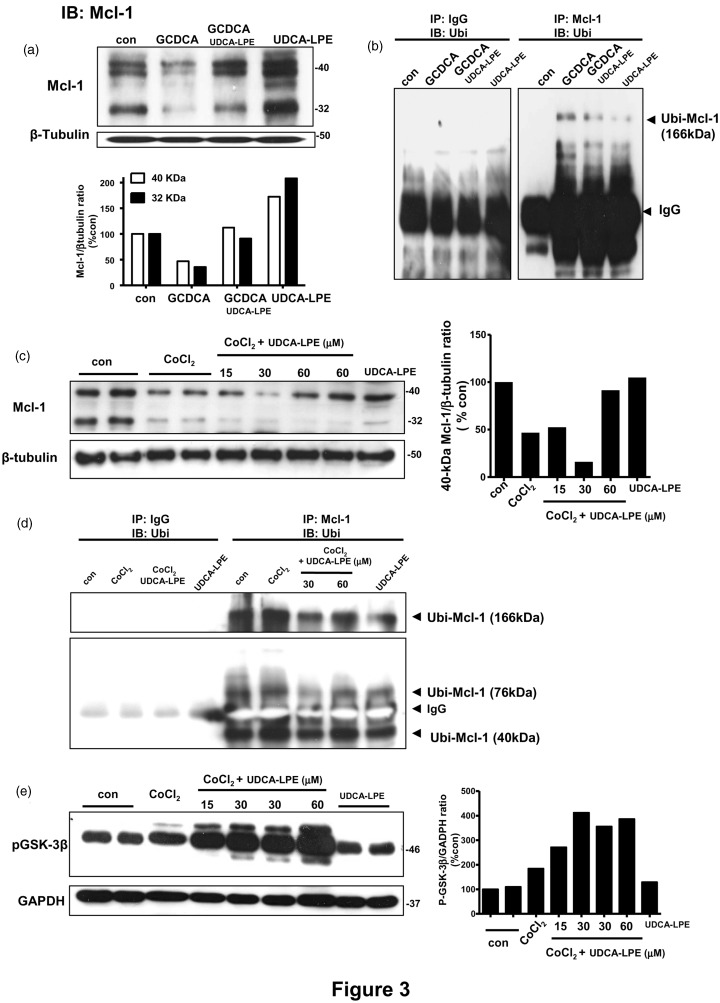

Mcl-1 is another anti-apoptosis protein which has been reported to be modulated during cholestasis27 and hypoxia.28 We explored whether UDCA-LPE could affect Mcl-1 expression, and whether proteasomal degradation of Mcl-1 could be modulated by UDCA-LPE.29 Following Mcl-1 IP and IB with ubiquitin antibody, we measured ubiquitinated Mcl-1 complex (Ubi-Mcl-1), which could be detectable at the molecular weights of Mcl-1 added with that of ubiquitin (9 kDa) multiple times upon polyubiquitination.

Under apoptosis induction, GCDCA treatment of mouse hepatocytes decreased expression of Mcl-1 proteins detectable at 40 kDa and 32 kDa, and UDCA-LPE co-treatment rescued these decreases as seen by densitometric analyses (Figure 3a). The rescue of Mcl-1 loss due to GCDCA was due to the ability of UDCA-LPE itself to significantly upregulate Mcl-1 protein. In GCDCA-treated mouse hepatocytes, Ubi-Mcl-1 complex was detected at 166 kDa (Figure 3b). For control experiments, IgG used instead of Mcl-1 antibody for IP did not produce this complex. This indicated an increased degradation of Mcl-1, thereby causing a decrease in Mcl-1 protein expression seen in Figure 3(a). UDCA-LPE co-treatment inhibited GCDCA-induced increases of 166-kDa Ubi-Mcl-1 complex (Figure 3b). Hence, UDCA-LPE attenuated the degradation of Mcl-1 resulting in Mcl-1 accumulation and apoptosis inhibition during cholestasis in mouse hepatocytes. In a similar fashion as mouse hepatocytes, CoCl2 treatment of Mz-ChA-1 cells decreased expression of 40-kDa and 32-kDa Mcl-1 proteins, and co-treatment of UDCA-LPE at 60 µM rescued the loss of 40-kDa Mcl-1 as seen by densitometric analyses (Figure 3c). Following IP, Ubi-Mcl-1 complexes detectable at ∼40 kDa, ∼76 kDa and ∼166 kDa were increased by CoCl2 treatment indicating increased Mcl-1 degradation (Figure 3d). UDCA-LPE co-treatment inhibited these increases resulting in Mcl-1 accumulation (Figure 3c) and apoptosis inhibition (Figure 2). IP with IgG did not produce any detectable Ubi-Mcl-1 complex in Mz-ChA-1 cells (Figure 3d). Of note, cIAP2 antibody did not work in pull-down assays and therefore we could not study possible proteasomal degradation in this experimental system.

Figure 3.

Ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide (UDCA-LPE) inhibited Mcl-1 degradation in cholestasis and hypoxia models. (a) Western blot (top) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (bottom) of Mcl-1 proteins detectable at 40 kDa and 32 kDa were obtained from control, GCDCA, GCDCA + 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes. (b) Lysates from control, GCDCA, GCDCA + 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated mouse hepatocytes were immunoprecipitated (IP) with Mcl-1 antibody and immunoblotted (IB) with ubiquitin antibody for detection of Ubi-Mcl-1 complex at 166 kDa. IP with IgG instead of Mcl-1 antibody was used in control experiments. (c) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels (right-hand plot for 40-kDa Mcl-1) of Mcl-1 proteins detectable at 40 kDa and 32 kDa were obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 15 µM, 30 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells. (d) Ubi-Mcl-1 complexes detectable at 166 kDa, 76 kDa and 40 kDa were obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 30 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1cells. IP with IgG instead of Mcl-1 antibody was used in control experiments. (e) Western blot (left) and GAPDH-normalized expression levels of phosphorylated GSK-3β (Ser9) were obtained from control, CoCl2, CoCl2 + 15 µM, 30 µM or 60 µM UDCA-LPE and 60 µM UDCA-LPE-treated Mz-ChA-1 cells

Mcl-1 degradation has been shown to be mediated by active glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3).30,31 GSK-3α/β is among few enzymes where its phosphorylation decreases the levels of active enzymes.32 We have previously shown that UDCA-LPE treatment of HepG2 cells increased phosphorylation of GSK-3α/β in support of prosurvival function in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.14 We therefore determined whether UDCA-LPE could affect GSK-3α/β phosphorylation in our hypoxia model. Here we utilized a primary human antibody specific for phosphorylated GSK-3β. Treatment of Mz-ChA-1 cells with CoCl2 or UDCA-LPE alone did not increase GSK-3β phosphorylation, while the combined CoCl2 and UDCA-LPE did in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3e). Thus, the observed increased GSK-3β phosphorylation by UDCA-LPE co-treatment reflected GSK-3β inactivation leading to an attenuation of Mcl-1 degradation (Figure 3c and d), and hence apoptosis inhibition (Figure 2).

Discussion

UDCA-LPE was herein shown to be effective in apoptosis inhibition in two cellular models of cholestasis and hypoxia, both of which are pathological consequence of hepatic I/R. UDCA-LPE affected both intrinsic mitochondrial and extrinsic apoptosis pathways in part by an accumulation of antiapoptotic cFLIP, cIAP2 and Mcl-1. For the latter case, we showed that UDCA-LPE inhibited the proteasomal degradation of Mcl-1 protein. Our work warrants the use of UDCA-LPE as a cytoprotective agent in an in vivo model of hepatic I/R.

Experimental cellular models of cholestasis and hypoxia were adopted for testing the efficacy of UDCA-LPE in mouse hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells, respectively. We observed that extrinsic apoptosis contributed significantly to overall apoptosis in the GCDCA/cholestasis model but not in the CoCl2/hypoxia model. UDCA-LPE itself was able to upregulate cFLIP, and this effect may have some influence on proteasomal degradation of other protective proteins.25 We observed that UDCA-LPE prevented the loss of cIAP2 and Mcl-1 proteins known to be involved in intrinsic apoptosis. It is known that hypoxic condition in vivo can induce cholestasis33 in part by upregulating bile acid transport genes.34 An upregulation of cFLIP and the prevention of the loss of cIAP2 and Mcl-1 by UDCA-LPE would result in the resolution of apoptotic injury caused by hypoxia, and cholestasis at prolonger time. In a liver transplantation setting, UDCA-LPE may be given prophylactic to the donor and the recipient before and after transplantation in order to prevent early and late onset of apoptosis due to I/R and cholestasis in a similar manner as UDCA.35

The mechanisms for UDCA-LPE’s ability to upregulate antiapoptosis proteins are still elusive. We surmise that UDCA-LPE may induce survival signals such as NF-κB, which in turn induces cFLIP36,37 and cIAP237. Long (55 kDa) and short (43 kDa) isoforms of cFLIP are structural homologs of caspase 8 by blocking the caspase in the death-inducing signalling complex (DISC)19, and phosphorylation of cFLIP stimulated by GCDCA was associated with decreased binding of cFLIP to DISC.20 Further experiments are warranted to determine the extent of cFLIP phosphorylation under GCDCA, UDCA-LPE and GCDCA + UDCA-LPE treatment in order to dissect the protection versus damaging effects of the observed increases of cFLIP proteins. The ability of UDCA-LPE to upregulate cFLIP on mRNA are consistent with a previous study38 showing the effects of dexamethasone during an inhibition of TNFα-induced apoptosis by transcriptional regulation of cFLIP. UDCA-LPE’s ability to upregulate cFLIP mRNA and protein under hypoxia and cholestasis, respectively, supports its potential role in inhibition of extrinsic apoptosis, which may occur at prolonger time after hepatic I/R injury.

In both stress models, UDCA-LPE was able to upregulate expression of Mcl-1 protein with a mechanism involving an inhibition of Mcl-1 degradation. We have previously shown that UDCA-LPE activates survival PI3K/Akt, which inhibits downstream GSK-3α/β signaling pathway.14 PI3K/Akt activation is suppressed during apoptosis, and that low Akt activity releases GSK-3 from inhibitory phosphorylation by Akt thus allowing the active GSK-3 to phosphorylate Mcl-1.30 Phosphorylated Mcl-1 is ubiquitinylated and rapidly degraded during apoptosis. The ability of UDCA-LPE to increase phospho-GSK-3β would result in an inhibition of Mcl-1 degradation. An inactivation of GSK-3β by UDCA-LPE observed in our hypoxia model is consistent with the use of specific inhibitor39 or silencing40 of GSK-3β in ameliorating the hepatocellular damage due to I/R injury and acetaminophen toxicity, respectively, by a mechanism involving preventing the loss of Mcl-1.

In addition to cFLIP and Mcl-1, the protection by UDCA-LPE was also mediated by preventing the loss of cIAP2 protein during hypoxia. However, unlike cFLIP and Mcl-1, UDCA-LPE alone did not upregulate cIAP2 protein expression. The mechanisms for the prevention of cIAP2 loss by UDCA-LPE are not known. cIAP2 normally functions by causing polyubiquitination of receptor-interacting protein 1 at the DISC thus blocking caspase 8 activation.41 The prevention of cIAP2 loss by UDCA-LPE could contribute to a weak inhibition of extrinsic apoptosis observed in hypoxia model. It is known that cIAP2 is induced by cAMP26 and NFκB.37,42 cIAP2 may be regulated by UDCA-LPE by elevating intracellular cAMP levels.15 UDCA-LPE may indirectly activate NFκB by inducing preferential synthesis of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA)15 which are activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α which enhances cytosolic IκB-α stability.42 This pathway is shown to be one of the mechanisms for protection against I/R injury.43 As we have shown that UDCA-LPE prevents TNF-α-induced apoptosis by stabilizing mitochondrial membrane,14 UDCA-LPE may additionally have an effect on the functions of mitochondrial proteins, such as Smac44 and DIABLO,45 which are known to bind and antagonize cIAPs.

In conclusion, we herein demonstrated that UDCA-LPE inhibited apoptosis during cholestasis and hypoxia by a mechanism of upregulation of antiapoptosis proteins. The ability of UDCA-LPE to upregulate cFLIP and cIAP2 was proposed to be via NFκB by which UDCA-LPE causes an increase of cAMP and preferential syntheses toward n-3 PUFA.15 UDCA-LPE was shown to inhibit proteasomal degradation of Mcl-1 via PI3K/Akt and GSK-3β signaling pathways. Our data suggest that UDCA-LPE may be protective in inhibiting intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis during hepatic I/R injury.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study is supported in part by Deustche Forschungsgemeinschaft (CH288/6-1; PA 2365/1-1; STR 216/15-4).

Authors’ contributions

MS conducted the experiments, performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. WX prepared mouse hepatocytes. AP designed the experiments and provided reagents. ST provided reagents and revised the manuscript. WC designed and supervised the experiments, and revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lemasters JJ, Thurman RG. Reperfusion injury after liver preservation for transplantation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1997; 37: 327–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katyal S, Oliver JH, Buck DG, Federle MP. Detection of vascular complications after liver transplantation. Am J Roentgenol 2000; 175: 1735–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutrin JC, Cantino D, Biasi F, Chiarpotto E, Salizzoni M, Andorno E, Massano G, Lanfranco G, Rizzetto M, Boveris A. Reperfusion damage to the bile canaliculi in transplanted human liver. Hepatology 1996; 24: 1053–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yasui H, Yoshimura N, Kobayashi Y, Ochiai S, Matsuda T, Takamatsu T, Oka T. Microstructural changes of bile canaliculi in canine liver: the effect of cold ischemia reperfusion in orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1998; 30: 3754–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geuken E, Visser D, Kuipers F, Blokzijl H, Leuvenink HG, de Jong KP, Peeters PM, Jansen PL, Slooff MJ, Gouw AS, Porte RJ. Rapid increase of bile salt secretion is associated with bile duct injury after human liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2004; 41: 1017–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greim H, Trulzsch D, Czygan P, Rudick J, Hutterer F, Schaffner F, Popper H. Mechanism of cholestasis. 6. Bile acids in human livers with or without biliary obstruction. Gastroenterology 1972; 63: 846–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faubion WA, Guicciardi ME, Miyoshi H, Bronk SF, Roberts PJ, Svingen PA, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ. Toxic bile salts induce rodent hepatocyte apoptosis via direct activation of Fas. J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoekstra H, Porte RJ, Tian Y, Jochum W, Stieger B, Moritz W, Slooff MJ, Graf R, Clavien PA. Bile salt toxicity aggravates cold ischemic injury of bile ducts after liver transplantation in Mdr2+/− mice. Hepatology 2006; 43: 1022–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ligeret H, Brault A, Vallerand D, Haddad Y, Haddad PS. Antioxidant and mitochondrial protective effects of silibinin in cold preservation-warm reperfusion liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol 2008; 115: 507–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kincius M, Liang R, Nickkholgh A, Hoffmann K, Flechtenmacher C, Ryschich E, Gutt CN, Gebhard MM, Schmidt J, Büchler MW, Schemmer P. Taurine protects from liver injury after warm ischemia in rats: the role of kupffer cells. Eur Surg Res 2007; 39: 275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falasca L, Tisone G, Palmieri G, Anselmo A, Di Paolo D, Baiocchi L, Torri E, Orlando G, Casciani CU, Angelico M. Protective role of tauroursodeoxycholate during harvesting and cold storage of human liver: a pilot study in transplant recipients. Transplantation 2001; 71: 1268–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindler G, Kincius M, Liang R, Backhaus J, Zorn M, Flechtenmacher C, Gebhard MM, Büchler MW, Schemmer P. Fundamental efforts toward the development of a therapeutic cocktail with a manifold ameliorative effect on hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Microcirculation 2009; 16: 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benz C, Angermuller S, Tox U, Kloters-Plachky P, Riedel HD, Sauer P, Stremmel W, Stiehl A. Effect of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on bile-acid-induced apoptosis and cytolysis in rat hepatocytes. J Hepatol 1998; 28: 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamulitrat W, Burhenne J, Rehlen T, Pathil A, Stremmel W. Bile salt-phospholipid conjugate ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide as a hepatoprotective agent. Hepatology 2009; 50: 143–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamulitrat W, Liebisch G, Xu W, Gan-Schreier H, Pathil A, Schmitz G, Stremmel W. Ursodeoxycholyl lysophosphatidylethanolamide inhibits lipoapoptosis by shifting fatty acid pools toward monosaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in mouse hepatocytes. Mol Pharmacol 2013; 84: 696–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knuth A, Gabbert H, Dippold W, Klein O, Sachsse W, Bitter-Suermann D, Prellwitz W, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Biliary adenocarcinoma. Characterisation of three new human tumor cell lines. J Hepatol 1985; 1: 579–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmeira CM, Rolo AP. Mitochondrially-mediated toxicity of bile acids. Toxicology 2004; 203: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iizaka T, Tsuji M, Oyamada H, Morio Y, Oguchi K. Interaction between caspase-8 activation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in glycochenodeoxycholic acid-induced apoptotic HepG2 cells. Toxicology 2007; 241: 146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scaffidi C, Schmitz I, Krammer PH, Peter ME. The role of c-FLIP in modulation of CD95-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 1541–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi H, Yoon JH, Grambihler A, Werneburg N, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Bile acids stimulate cFLIP phosphorylation enhancing TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sánchez-Pérez T, Ortiz-Ferrón G, López-Rivas A. Mitotic arrest and JNK-induced proteasomal degradation of FLIP and Mcl-1 are key events in the sensitization of breast tumor cells to TRAIL by antimicrotubule agents. Cell Death Differ 2010; 17: 883–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Yang SJ, Kim YS, Kim TU. Cobalt chloride-induced apoptosis and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activation in human cervical cancer HeLa cells. J Biochem Mol Biol 2003; 36: 468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung JY, Kim WJ. Involvement of mitochondrial- and Fas-mediated dual mechanism in CoCl2-induced apoptosis of rat PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett 2004; 371: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petit A, Mwale F, Zukor DJ, Catelas I, Antoniou J, Huk OL. Effect of cobalt and chromium ions on bcl-2, bax, caspase-3, and caspase-8 expression in human U937 macrophages. Biomaterials 2004; 25: 2013–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishioka T, Katayama R, Kikuchi R, Nishimoto M, Takada S, Takada R, Matsuzawa S, Reed JC, Tsuruo T, Naito M Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by cellular FLIP. Genes Cells 2007;12:735-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Nishihara H, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Insel PA, Eckmann L. Inhibition of apoptosis in normal and transformed intestinal epithelial cells by cAMP through induction of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP)-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100: 8921–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beilke LD, Aleksunes LM, Olson ER, Besselsen DG, Klaassen CD, Dvorak K, Cherrington NJ. Decreased apoptosis during CAR-mediated hepatoprotection against lithocholic acid-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Lett 2009; 188: 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee M, Lapham A, Brimmell M, Wilkinson H, Packham G. Inhibition of proteasomal degradation of Mcl-1 by cobalt chloride suppresses cobalt chloride-induced apoptosis in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. Apoptosis 2008; 13: 972–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, Wang X. Mule/ARF-BP1, a BH3-only E3 ubiquitin ligase, catalyzes the polyubiquitination of Mcl-1 and regulates apoptosis. Cell 2005; 121: 1085–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maurer U, Charvet C, Wagman AS, Dejardin E, Green DR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis by destabilization of MCL-1. Mol Cell 2006; 21: 749–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Y, Altman BJ, Coloff JL, Herman CE, Jacobs SR, Wieman HL, Wofford JA, Dimascio LN, Ilkayeva O, Kelekar A, Reya T, Rathmell JC. Glycogen synthase kinase 3alpha and 3beta mediate a glucose-sensitive antiapoptotic signaling pathway to stabilize Mcl-1. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27: 4328–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J 2001; 359: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toki F, Takahashi A, Suzuki M, Ootake S, Hirato J, Kuwano H. Development of an experimental model of cholestasis induced by hypoxic/ischemic damage to the bile duct and liver tissues in infantile rats. J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 639–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fouassier L, Beaussier M, Schiffer E, Rey C, Barbu V, Mergey M, Wendum D, Callard P, Scoazec JY, Lasnier E, Stieger B, Lienhart A, Housset C. Hypoxia-induced changes in the expression of rat hepatobiliary transporter genes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007; 293: G25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowak G, Norén UG, Wernerson A, Marschall HU, Möller L, Ericzon BG. Enteral donor pre-treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid protects the liver against ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Transpl Int 2005; 17: 804–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreuz S, Siegmund D, Scheurich P, Wajant H. NF-kappaB inducers upregulatecFLIP, a cycloheximide-sensitive inhibitor of death receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21: 3964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halder UC, Bhowmick R, Roy Mukherjee T, Nayak MK, Chawla-Sarkar M Phosphorylation drives an apoptotic protein to activate antiapoptotic genes: paradigm of influenza A matrix 1 protein function. J Biol Chem 2013;288:14554-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 38.Oh HY, Namkoong S, Lee SJ, Por E, Kim CK, Billiar TR, Han JA, Ha KS, Chung HT, Kwon YG, Lee H, Kim YM. Dexamethasone protects primary cultured hepatocytes from death receptor-mediated apoptosis by upregulation of cFLIP. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 512–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren F, Duan Z, Cheng Q, Shen X, Gao F, Bai L, Liu J, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Zhai Y. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta ameliorates liver ischemia reperfusion injury by way of an interleukin-10-mediated immune regulatory mechanism. Hepatology 2011; 54: 687–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shinohara M, Ybanez MD, Win S, Than TA, Jain S, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N. Silencing glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibits acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and attenuates JNK activation and loss of glutamate cysteine ligase and myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 8244–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertrand MJ, Milutinovic S, Dickson KM, Ho WC, Boudreault A, Durkin J, Gillard JW, Jaquith JB, Morris SJ, Barker PA. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell 2008; 30: 689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varfolomeev E, Goncharov T, Fedorova AV, Dynek JN, Zobel K, Deshayes K, Fairbrother WJ, Vucic D. c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 are critical mediators of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha)-induced NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 24295–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zúñiga J, Cancino M, Medina F, Varela P, Vargas R, Tapia G, Videla LA, Fernández V. N-3 PUFA supplementation triggers PPAR-α activation and PPAR-α/NF-κB interaction: anti-inflammatory implications in liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS One 2011; 6: e28502–e28502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell 2000; 102: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verhagen AM, Ekert PG, Pakusch M, Silke J, Connolly LM, Reid GE, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ, Vaux DL. Identification of DIABLO, a mammalian protein that promotes apoptosis by binding to and antagonizing IAP proteins. Cell 2000; 102: 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]